Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The use of technology is changing the way things are done, including the work in universities where the teaching and learning process are changing, and it is required to know the effect of technology on student achievement. In this research work, we present the influence of Internet use on academic success of students from five universities in Ecuador. A random sample of 4,697 people was got up and categorized in two groups: the use of Internet in academic activities and entertainment, using factor analysis and cluster analysis; the resulting categories were used as independent variables in multinomial logistic regression model which are seeking to determine if the use of Internet has impacted on academic success. The results show that people who perform interactive activities with peers and teachers or use in a balanced way the different internet tools tend to have more academic success than those who only seeks information. Regarding to the use of Internet in entertainment, a positive impact was found on academic achievement. Students who download audio, video and software, and students who use all the entertainment possibilities show less likely to fail than who using minimally Internet. In terms of gender, it has different effects for entertainment and academic purposes.

1. Introduction

Academic achievement among students generally equates to the effort expended, and is related to intellectual and environmental factors. Habits acquired at an early age such as an interest in reading, or a lack of resources with which to develop elementary capabilities such as verbal comprehension and production are also an influence (Lucas, 1998).

Academic achievement is multidimensional and shaped by variables that are difficult to systematize within a specific model (Fullana, 1992). Educational success is usually measured by rudimentary testing that fails to take into account basic cognitive dimensions that form part of a systematic process. Variables can be personal, academic or social (Fullana, 1992). In recent years, several approaches have developed around the Bloom taxonomy (Bloom & al., 1956) that more or less coalesces around three psychological domains: cognitive, affective and psychomotor. There has also been a boom in instruction in, and assessment of, competences that insists on the need to develop generic and transversal competences, as well as those skills specific to each study area (Villa & Poblete, 2007), teaching students to «learn how to learn» and to acquire greater capacities in line with today’s ever-changing times. Academic achievement can be measured from various perspectives: efficacy, for example, grading the level of success in reaching set objectives in a course program, which provides important information for decision makers in educational institutions. A study by Duart & al. (2008) analyzed universities in Catalonia (Spain) and used as main indicator the relation between the number of subjects passed against the number of subjects students had matriculated for, thus enabling students to be categorized in terms of high, medium and low academic achievement. Other variables included gender, age and socio-economic strata. For gender, women outnumbered men by 10% in the high academic achievement category, and for age, students under 25 got better academic results.

Since then, technology has been added to the traditional indicators of academic achievement, meaning the technological environment at institutional level, access to Internet and how students use it, factors which Duart & al. (2008) define as «new determinants of academic achievement», and which influence students’ work on various levels and in different ways. An educational institution’s technological environment, if properly established, is an important factor in the development of a culture of technological usage. Although this by no means guarantees academic success, it does enable the student to develop good practices that can contribute to achieving academic goals. Duart and Lupiáñez-Villanueva (2005) pinpointed three areas in which the university as an institution had undergone changes: technological infrastructure, innovation among teachers and organizational restructuring. As a result, the most relevant factors affecting students on entering university are the level of technology within the educational model and the need to apply it to the development of the curriculum map, and the role of the teacher in directing students in the use of the information and technology available as learning tools and resources.

Various studies have found that Internet use can have positive benefits on educational achievement while others conclude that this outcome is not so obvious (Chen & Fu, 2009; Gil-Flores, 2009; Hunley & al., 2005; Luaran & al., 2011; Raines, 2012; Suhail & Bargees, 2006). The variables used to measure the influence of Internet use on academic success include student online activity for task completion, time spent on the Internet, and access to a computer and Internet connection at home. However, no firm conclusions are drawn on the issue since results from other studies performed under similar conditions have been contradictory (Antonijevic, 2007; Azizi, 2014; Ellore & al., 2014; Junco, 2015). Other studies show that the use of technology has a positive effect on certain cognitive areas such as the development of spatial skills and memory, and improved reading, writing and information processing skills, but this does not necessarily lead to better academic achievement. This fits with the Fullana concept (1992) of multidimensional forms of mediation. Heyam (2014) carried out a meta-analysis of the use of technology, in particular social networks, with regard to student performance, and drew two conclusions: technology and social networks facilitate communication, socialization, coordination, collaboration and entertainment; but they can also cause addiction and lead to time wasting, information overload and physical isolation from society.

Other studies have found relations between the use of technology and factors associated to academic achievement, one such being Gil-Flores (2009) who saw a significant link between computer usage and educational success. This study found that high school students who use a computer at home more often scored higher marks in maths and languages. Although Internet was not a determining factor, it at least establishes a relation between the variables. Another study involving high school students (Ndege & al., 2015) indicates the positive effects of technology in boosting the potential for communication and interaction, as well as the downside, which is that time is often wasted, leading to less time spent on academic activities.

Mishra & al. (2014) carried out a study of university students that analyzed the relation between the average of student scores and the time spent searching on Internet. The results revealed a significant negative relation in that the more time spent online, the lower the average mark. They also found a significant positive relation between the perception of the time students thought they needed to spend on sites with academic information and the average mark. Türel and Toraman (2015) found that men tend to spend more time online than women. They also concluded that as the average mark considered to be a good pass rose, so Internet addiction declined. So, the control should center on students who use Internet more than three hours a day. Lepp & al. (2015) measured the impact of cell phone use on the average marks scored by university students, and found that the greater the cell phone use, the lower the average.

Chen & Fu (2009) concluded that online information searching improved exam results. Other studies in Pakistan found that Internet use had a positive effect on marks, and improved reading, writing and information processing skills (Suhail & Bargees, 2006). Computer resources such as games had a positive effect on spatial skills and memory, as well as developing visual and auditory capacities, thus stimulating overall student development (Subrahmanyam & al., 2001). One recurring element in the studies is the relation between academic achievement and home computer access. On the other hand, no link has been established between academic achievement and computer use at the educational center (Gil-Flores, 2009). Other studies show that students who search out information online get better marks because they have access to more data sources and are thus better informed on the subject (Leung & Lee, 2012). This fits with Kupczynski & al. (2011) who studied the behavior of students in Internet courses, finding that the most active (higher number of online sessions) had greater educational success. Castaño (2011) highlighted the benefits of student interaction for academic achievement, with the benefits accruing more to online students than to those who physically attended classes.

Sciences in general and certain subjects in particular vary in the approach required for studying them, and technology can make a positive or negative contribution to learning. A study by Antonijevic (2007) found that computer use proved very valuable for science students but had the opposite effect on maths students. The use of technology in learning directly affects academic achievement. This is evident in a study by Wittwer and Senkbeil (2008) who discovered no link between computer access and performance in maths. However, using a computer to solve problems had a positive effect on students.

When it comes to entertainment, there is a marked difference in gender, as young women tend towards social networks while young men prefer online gaming (Fernández, Peñalba, & Irazabal, 2015). Young people who present an addiction to Internet usage also have lower academic achievement (Frangos, Frangos, & Kiohos, 2010). The trend is for students to score lower marks the more time they spend on online gaming (Ip, Jacobs & Watkins, 2008). Pepe (2011) found similar results in primary school students. Results tend to show that the time spent searching for information on Internet helps to raise marks and improve socialization whereas time spent online gaming has the opposite effect (Chen & Fu, 2009). Hunley & al. (2005) showed that the amount of time spent on the Internet had limited effect on high school students’ academic achievement, yet GPA test scores show no relation to specific online activities such as information search, use of email and videogames. This contradiction in the results of various studies reveals the need for deeper investigation in order to probe systematically the true nature of academic achievement and its determinants. This could shed light on the beneficial uses of technology on academic work, and inform teachers on how best to instruct students in the use of technology.

2. Material and methods

Two hypotheses were posed, which stated that the use of technology for both academic and entertainment purposes had a positive effect on academic achievement.

2.1. Population and sample

The sample was selected from students attending five universities in Ecuador between February and May 2015. A total of 4,697 students were surveyed at random, of whom 48.5% were men and 51.5% were women.

2.2. Data-gathering instruments

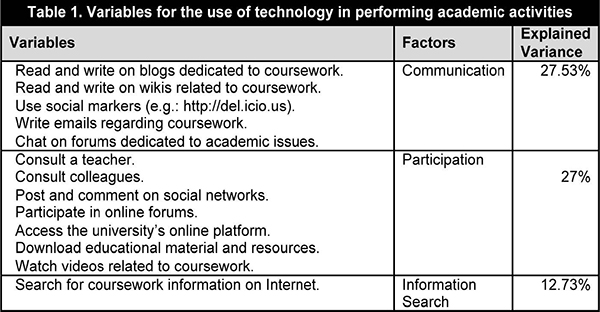

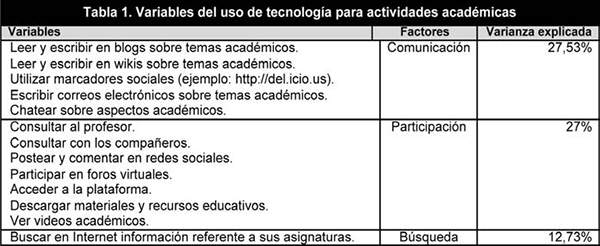

A tool was developed based on questionnaires used in the Proyecto Internet Cataluña (UOC, 2003) and the Digital Literacy in Higher Education Project (DLINHE, 2011), and adapted to the requirements of this research. The questionnaire did not require students to state which degree course they were studying. It was divided in two parts, the first containing 13 questions on the use of technology for performing academic activities; the variables are presented in table 1.

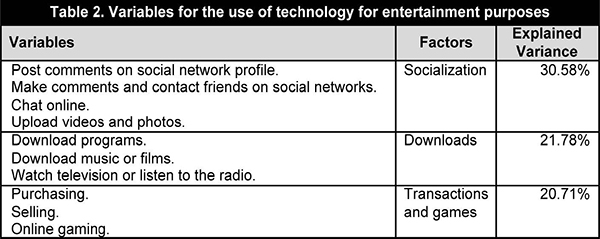

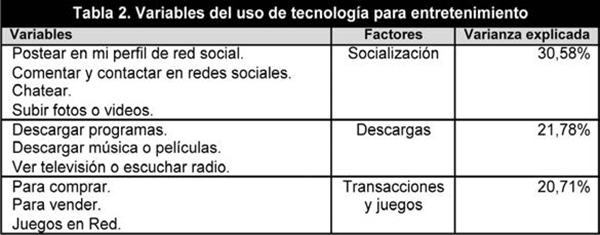

The second part of the questionnaire extracted information on the use of technology for entertainment by means of 10 variables, presented in table 2. It also gathered socio-demographic information using the variables of age, gender and income, the latter measured on a five-level scale. Information on academic achievement was obtained from two variables that asked the students how many subjects were taking and how many they had failed in the last semester.

2.3. Procedure

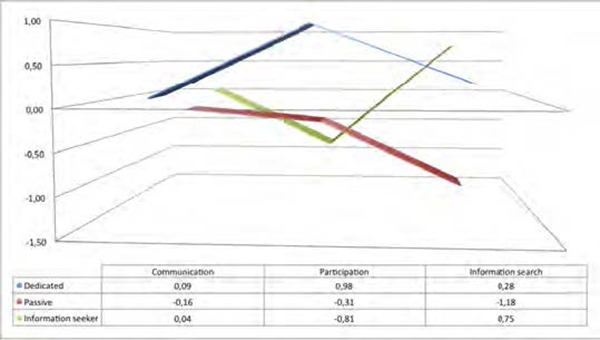

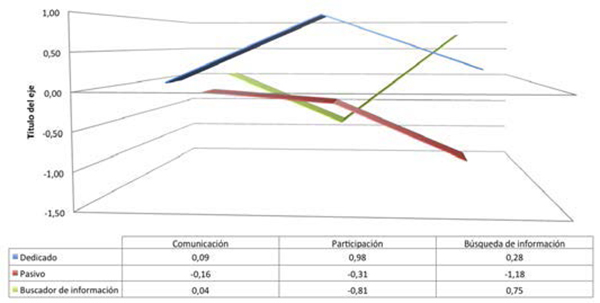

We created a variable to represent Internet use for academic activities and another for Internet use for entertainment, so students were classified according to the use of technology for coursework or for entertainment. To construct the «academic uses» variable, we presented 13 questions to measure the use of various technological instruments in academic activities (table 1), and a factor analysis was performed to reduce the number of variables and group them in factors. The factors were Communication, Participation and Information Search, and they were subject to a k-means clustering analysis. To guarantee the consistency of the classifications, groups were created by first calculating the centroids from a subsample and then using them to generate the groups. Students were classified in 2, 3, 4 and 5 groups, from which one was selected that presented the greatest accuracy and best ease of interpretation of the groups’ structure, following a discriminant function analysis. This analysis was carried out using the group number generated by the cluster analysis as a dependent variable, and the factors from the factor analysis as independent variables (Cea, 2005; Díaz-De-Rada, 1998; Shunglu & Sarkar, 1995). This enabled us to determine the percentage of elements correctly assigned to each classification. We then divided the classification into three groups, as the easiest way to interpret them, and the three groups’ centroids for each variable are shown in figure 1.

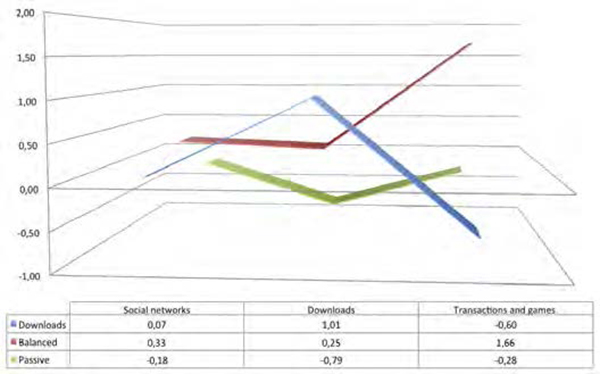

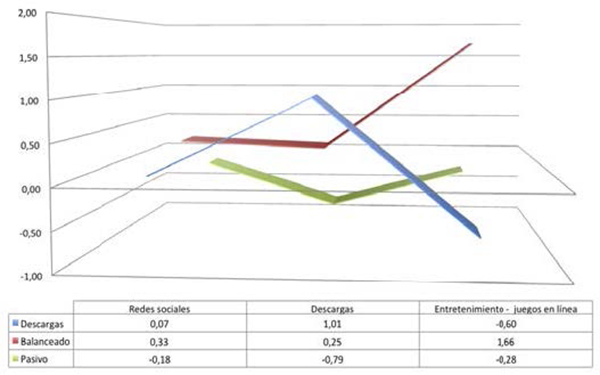

A similar procedure was applied to develop classification based on the use of Internet for entertainment. The variables used and the resulting factors from the factor analysis are shown in table 2. The final categories of this classification are shown in figure 2.

We also created a variable to represent academic achievement, so students were categorized in four groups according to the number of subjects failed. This was obtained by subtracting the number of subjects passed from the number of subjects taken (subjects failed = subjects taken, subjects passed). This gave us four categories: no subject failed, one failed, two failed, more than two failed. The correlations established are: the uses of the Internet for academic activities and academic achievement, and the uses of the Internet for entertainment and academic achievement. The correlations were obtained using multinomial logistic regression models.

Figure 1. Groups according to use of technology

3. Results

3.1. Categorization of the students

Classification based on the uses of the Internet for academic activities divides the students into three groups (figure 1) or profiles: the dedicated academic profile scores high in all factors, especially in Participation, which is its distinctive element and refers to interactive activities and work carried out using educational material. The homogeneity in the values for this profile demonstrates a balanced use of Itools. In the Communication factor, there is a similarity between the information seeker academic profile and the dedicated profile. The information seeker academic profile presents the lowest values in the Participation factor and the highest in Information Search. Its main characteristic contains a contradiction in that it has a high level of information search and a low level of interactive activities and work with educational material, which indicates an imbalance in the use of Internet tools. Finally, the passive academic profile has its lowest levels of intensity in information search and the use of social network tools; and the intensity levels are low for interactive activities and work with educational material, yet they are higher than those for the information seeker profile.

Figure 2. Groups according to use of technology for academic activities.

Classification of students based on the uses of the Internet for entertainment activities divides them into three groups (figure 2). The first is the download entertainment profile and is composed of 32.4% of the students surveyed; it has the highest level of downloads of programs, music, films and radio and television content. Men are in a majority in this group, at 57.2%. Group 2 is the balanced entertainment profile so-called because the components’ usage of all forms of entertainment is more or less homogenous; it numbers 19.8% of the students and most are men, 58.3%. Its distinctive feature is the high level of buying and selling that takes place, as well as the preference for online gaming. Group 3 is the passive entertainment profile which accounts for 47.8% of students, and these have the lowest level of Internet use for entertainment. They tend to be the oldest in the sample and are mainly women, 61.5%. The low level of technology use for entertainment points to a student who does not deem online entertainment to be important, or who has restricted access to technology or no time to use it.

3.2. Educational uses of the Internet and academic achievement

One of the hypotheses tested in this research is that Internet use for doing coursework has a positive effect on academic achievement. The use of technology for carrying out educational tasks is grouped according to profile denomination that reveals the differences between them. The main divergence is between the dedicated profile and information seeker profile, which is apparent in the level of interaction activities and the work carried out with educational material; this is high in the dedicated profile and very low in the information seeker profile.

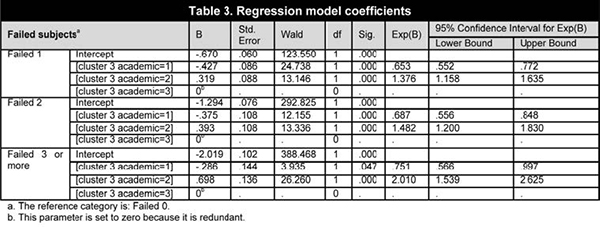

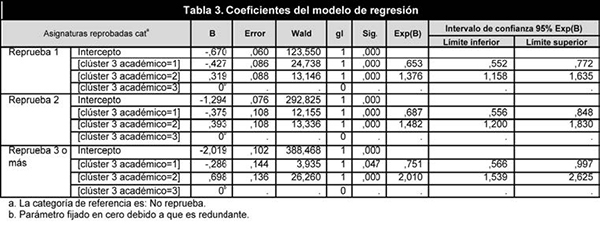

The likelihood ratio of failing one subject as opposed to failing none diminishes 1.53 (1/0.65) times when the student belongs to the dedicated student profile in relation to the information seeker academic profile. The likelihood ratio of failing one subject as opposed to failing none increases 1.37 times when the student belongs to the passive academic profile in relation to the information seeker academic profile. The likelihood ratio of failing two subjects against failing none is 1.45 (1/0.68) times less when the student belongs to the dedicated academic profile in relation to the information seeker academic profile, and is 1.48 times greater when the student belongs to the passive academic profile in relation to the information seeker academic profile. The likelihood ratio of failing three or more subjects against failing none is 1.33 (1/0.75) times less when the student belongs to the dedicated academic profile in relation to the information seeker academic profile, and is 2.01 times greater when the student belongs to the passive academic profile in relation to the information seeker academic profile.

3.3. Entertainment and academic achievement

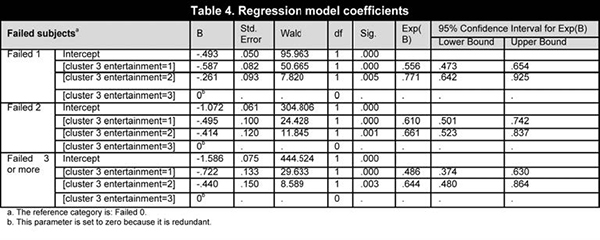

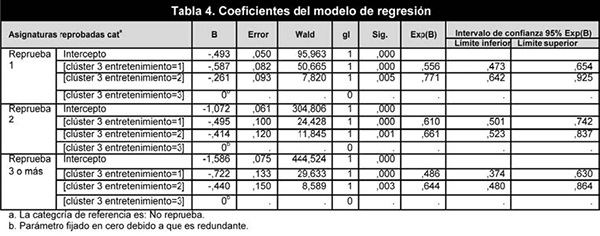

The second hypothesis sustains that the use of Internet for entertainment activities influences students’ academic performance. An important finding in our study is that students who use Internet for entertainment purposes less tend to fail more often (table 4). The likelihood of failing one subject as opposed to failing none is 1.78 (1/0.55) times less when a student belongs to the download entertainment profile in relation to the passive profile; and is 1.29 (1/0.77) times less when the student belongs to the balanced entertainment profile in relation to the passive profile.

Something similar occurs when we analyze students who failed two subjects. The probability of failing two subjects in relation to failing none is 1.64 times less when the student belongs to the download entertainment profile in relation to the passive profile; and is 1.51 times less when the student belongs to the complete entertainment profile in relation to the passive profile.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Although the use of technology to perform academic activities determines only 3% of academic performance its effect is visible, depending on the type of usage. Students who tend to interact more and use educational material (dedicated profile) are less likely to fail than students whose main academic activity is to search for information (information seeker profile). These findings differ from those of Chen & Fu (2009) who sustained that searching for information on Internet enhanced academic achievement. The differences between the dedicated and information seeker profiles and their effect on academic achievement coincide with hypotheses that state that the digital divide is not solely due to Internet connection or access to technology (Warschauer, 2002; Zillien & Hargittai, 2009) but also to good use of technology and resources, as is the case of the dedicated profilers who present habits that are considered proper and balanced.

The passive profile has the lowest levels of technological use, which presumes that the student is conditioned by restrictions (income, knowledge, access to a connection); and the negative effect on academic achievement is clear since those whose use of the Internet tools for coursework is minimal (passive profile) tend to fail more subjects than those whose output is based on online information searching (information seeker profile). The lack of access to the Internet has an even greater negative impact than bad practices or habits in technology use. It also emphasizes the disadvantage suffered by those with fewer economic resources, thereby reinforcing the knowledge gap theory (Tichenor, Donohue, & Olien, 1970).

This study shows that students have greater academic success when they make a balanced use of Internet tools for their coursework; they more often get involved in interactive academic activities and make greater use of educational material, which fits with Castaño (2011) who showed the positive effects of interaction. On the other hand, students whose use of the Internet is categorized as passive score lower in testing.

Our study found that the influence of Internet use on academic achievement was significant, in line with Mishra & al. (2014) and Türel and Toraman (2015). Further research needs to focus on the time spent on the Internet for academic purposes in order to measure the true extent of this relation, so it should look to the most influential variables from our study, such as those related to interaction and working with educational material.

A significant percentage (30%) of students use Internet only for information searching and not for interacting with teachers or colleagues or using course material. This seems to be a strange behavior and further research is needed to determine whether it is an inappropriate practice or a new ad hoc methodology that is becoming a dynamic structure in students’ technological practices. The use of the Internet for academic work is not influenced by gender, as both men and women present the same patterns for technology use.

In terms of entertainment-related activities, we found that the Internet use for entertainment had a positive influence on academic achievement, contrary to Ip & al. (2008). The reason is unclear so more data is needed on the time students spend on each entertainment activity. In general, students who download files and use the Internet extensively for entertainment purposes tend to fail fewer subjects than those who do not use the Internet, or rarely use it, for entertainment.

Regardless of whether students fail one, two or more subjects, the download profilers make more extensive use of the Internet for entertainment purposes. These students are less likely to fail than those who belong to the complete profile, whose level of technology use for entertainment is high and balanced. Although data on this finding are not abundantly clear, analysis of the similarities and differences between the two profiles reveals that the biggest divergence relates to the extent of buying and selling activities, and online gaming, with the latter perhaps being the most significant (Ip & al., 2008), which is why we extracted the percentage of students who play online in each profile, with download profilers playing less online (53.3%) than the complete profilers (87.7%). This could explain why the complete profile students have lower academic achievement. Although this finding is interesting, it requires more conclusive evidence. Future research needs to work on more variables, one such being the time students spend on online gaming.

Our finding, that students who use technology for entertainment generally tend to score higher in tests, runs contrary to several studies (Frangos & al., 2010; Ip & al., 2008; Mishra & al., 2014; Pepe, 2011; Türel & Toraman, 2015). Data supporting this finding is minimal, other than the fact that the level of influence of entertainment on academic achievement is 1.9% of the explained variance.

When comparing students who perform a wide range of online entertainment activities (balanced profile) to those whose use is limited (passive profile), women are twice as likely to belong to the latter group. In other words, women tend to make less use of technology for entertainment. On the other hand, comparing balanced profilers to downloaders, both men and women are equally represented and no clear trend is visible. We can conclude that in terms of entertainment women prefer to download information than play games online.

References

Antonijevic, R. (2007). Usage of Computers and Calculators and Students’ Achievement: Results from TIMSS 2003. En International Conference on Informatics, Educational Technology and New Media in Education. Sombor, Serbia. (http://goo.gl/2zJ54R) (2015-03-18).

Azizi, E. (2014). Relationship between Internet Competency and Academic Achievement of Science Students in Bachelor Level. Research Journal of Recent Sciences, 3(9), 34-38. (http://goo.gl/oHBJZI) (2015-03-23).

Bloom, B., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I, The Cognitive Domain. New York: Adison-Wesly.

Castaño, J. (2011). El uso de Internet para la interacción en el aprendizaje: Un análisis de la eficacia y la igualdad en el sistema universitario catalán. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. (http://goo.gl/hZW1Rs) (2015-05-22).

Cea, M.A. (2005). La exteriorización de la xenofobia. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 112(5), 197-230. (https://goo.gl/B9TU43) (2015-02-28).

Chen, S.Y., & Fu, Y.C. (2009). Internet Use and Academic Achievement: Gender Differences in Early Adolescence. Adolecense, 44(176). (http://goo.gl/ZzkiOW) (2015-04-14).

Díaz-De-Rada, J.V. (1998). Diseño de tipologías de consumidores mediante la utilización conjunta del Análisis Cluster y otras técnicas multivariantes. Revista Española de Economía Agraria, 182, 75-104. (http://goo.gl/QNbNGG) (2015-03-23).

Dlinhe (2011). Digital Literacy in Higher Education. (https://goo.gl/dcQ4gj) (2015-02-17).

Duart, J. M., Gil, M., Puyol, M., & Castaño, J. (2008). La universidad en la sociedad Red. Barcelona: Ariel.

Duart, J.M., & Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F. (2005). E-strategies in the Introduction and Use of Information and Communication Technologies in the University. Universities and Knowledge Society Journal, 2(1). doi http://doi.org/10.7238/rusc.v2i1.243

Ellore, S.B., Niranjan, S., & Brown, U. (2014). The Influence of Internet Usage on Academic Performance and Face-to-Face Communication. Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science, 2(2), 163-186. (http://goo.gl/7En0YU) (2015-03-02).

Fernández, J., Peñalba, A., & Irazabal, I. (2015). Internet Use Habits and Risk Behaviours in Preadolescence. [Hábitos de uso y conductas de riesgo en Internet en la preadolescencia]. Comunicar, 44, 113-120. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C44-2015-12

Frangos, C., Frangos, C., & Kiohos, A. (2010). Internet Addiction among Greek University Students: Demographic Associations with the Phenomenon, Using the Greek Version of Young’s Internet Addiction Test. International Journal of Economic Sciences and Applied Research, 3(1), 49-74. (http://goo.gl/xr1RnX) (2015-03-05).

Fullana, J. (1992). Revisió de la recerca educativa sobre les variables explicatives del rendiment acadèmic: Apunt per a l’ús del criteri de 'modificabilitat pedagògica' de les variables. Estudi General, (12), 185-200. (http://goo.gl/ejXqcc) (2015-03-10).

Gil-Flores, J. (2009). Computer Use and Students' Academic Achievement. Research, Reflections and Innovations in Integrating ICT in Education (Internet). (http://goo.gl/ODCcGT) (2015-02-27).

Heyam, A. (2014). The Influence of Social Networks on Students' Performance. Journal of Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Sciences, 5(3), 200-205. http://doi.org/10.3916/C41-2013-19

Hunley, S., Evans, J., & al. (2005). Adolescent Computer Use and Academic Achievement. Adolecense, 40(158), 307-318. (http://goo.gl/2qPR7q) (2015-03-11).

Ip, B., Jacobs, G., & Watkins, A. (2008). Gaming Frequency and Academic Performance. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 24(4), 355-373. (http://goo.gl/7mO0M5) (2015-02-17).

Junco, R. (2015). Student class standing, Facebook Use, and Academic Performance. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 36, 18-29. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.001

Kupczynski, L., Gibson, A.M., Ice, P., Richardson, J., & Challoo, L. (2011). The Impact of Frequency on Achievement in Online Courses: A Study From a South Texas University. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 10(3), 141–149. (http://goo.gl/PNbNJT) (2015-02-03).

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2015). The Relationship between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students. SAGE Open, 5(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015573169

Leung, L., & Lee, P. (2012). Impact of Internet Literacy, Internet Addiction Symptoms, and Internet Activities on Academic Performance. Social Science Computer Review, 30(4), 403-418. doi: http://doi.org/10.1177/0894439311435217

Luaran, J. E., Binti, F., Mohd, K., & Nadzri, F. (2011). Hooked on the Internet:How does it Influence the Quality of Undergraduate Student’s Academic Performance? (http://goo.gl/67QNHr) (2015-02-20).

Lucas, M. L. (1998). Family Background, Home Environment and the Rate of Child Cognitive Development. Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Texas y Dallas.

Mishra, S., Draus, P., Goreva, N., Leone, G., & Caputo, D. (2014). The Impact of Internet Addiction on University Students and Its Effect on Subsequent Academic Success: a Survey Based Study. Issues in Information Systems, 15(I), 344-352. (http://goo.gl/H88TK3) (2015-03-30).

Ndege, W., Teresia, M., & al. (2015). Social Networks and Students’ Performance in Secondary Schools?: Lessons from an Open Learning Centre, Kenya. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(21), 171-178. (https://goo.gl/RpGBBd) (2015-03-26).

Pepe, K. (2011). A Study on the Playing of Computer Games, Class Success and Attitudes of Parents to Primary School Students. Educational Research and Reviews, 6(9), 657-663. (http://goo.gl/RR0u8i) (2015-04-16).

Raines, J. (2012). The Effect of Online Homework Due Dates on College Student Achievement in Elementary Algebra. Journal of Studies in Education, 2(3), 1-18. doi: http://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v2i3.1704

Shunglu, S., & Sarkar, M. (1995). Researching the Consumer. Marketing and Research, 23(2), 123-131. (https://goo.gl/ZPzpkt) (2015-03-30).

Subrahmanyam, K., Greenfield, P., Kraut, R., & Gross, E. (2001). The Impact of Computer Use on Children’s and Adolescents Development. Applied Developmental Psychology, 22(1), 7-30. (http://goo.gl/HRv5L) (2015-03-23).

Suhail, K., & Bargees, Z. (2006). Effects of Excessive Internet use on Undergraduate Students in Pakistan. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(3), 297-307. (http://goo.gl/fVV2aF) (2015-03-28).

Tichenor, P., Donohue, G., & Olien, C. (1970). Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge, Public Opinion Quarterly 34: . Public Opinion Quarterly, 34(2), 150-170. (http://goo.gl/MwCcJ0) (2014-04-10).

Türel, Y.K., & Toraman, M. (2015). The Relationship between Internet Addiction and Academic Success of Secondary School Students. Antropologist, 20, 280-288. (http://goo.gl/npyrwt) (2015-03-30).

UOC (Ed.) (2003). Internet Catalonia Project. (http://goo.gl/G3xmXT) (2015-04-20).

Villa, A., & Poblete, M. (2007). Aprendizaje basado en competencias una propuesta para la evaluación de las competencias genericas. Bilbao: Mensajero.

Warschauer, M. (2002). Reconceptualizing the Digital Divide. First Monday, 7(7). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v7i7.967

Wittwer, J., & Senkbeil, M. (2008). Is Students’ Computer Use at Home Related to their Mathematical Performance at School? Computers & Education, 50(4), 1.558-1.571. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.03.001

Zillien, N., & Hargittai, E. (2009). Digital Distinction: Status-Specific Types of Internet Usage. Social Science Quarterly, 90(2), 274-291. doi: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00617.x

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El uso de la tecnología provoca cambios sociales. Esto incluye el trabajo en el ámbito universitario en donde está cambiando tanto la forma de ejercer la docencia como la forma de aprender y se requiere conocer el efecto del uso de la tecnología sobre el rendimiento del alumnado. En este trabajo se investigó la incidencia del uso de Internet sobre el éxito académico del alumnado de cinco universidades de Ecuador. Se levantó una muestra aleatoria de 4.697 personas y se las categorizó en perfiles de uso de Internet para actividades académicas y para entretenimiento, utilizando análisis factorial y análisis clúster. Las categorías resultantes se utilizaron como variables independientes en modelos de regresión logística multinomial que buscaban determinar si el uso de Internet tenía incidencia sobre el éxito académico. Los resultados muestran que quienes realizan actividades interactivas con pares y profesores o quienes utilizan de forma balanceada las distintas herramientas de Internet tienden a un mayor éxito académico que aquellos que solo buscan información. En lo referente al entretenimiento, se encontró una incidencia positiva del uso de Internet sobre el éxito académico. Los estudiantes que realizan descargas de contenido de audio, video y software, y quienes utilizan todas las posibilidades de entretenimiento, presentan menor tendencia a suspender que los estudiantes que utilizan mínimamente Internet. En cuanto al género se presentan diferencias en los usos académicos y de entretenimiento.

1. Introducción

El rendimiento académico de un estudiante generalmente se corresponde con el esfuerzo empleado. Está relacionado con una serie de factores tanto intelectuales como ambientales. En él pueden influir hábitos asimilados a edades tempranas como el interés por la lectura o por la falta de medios para alcanzar capacidades elementales como la comprensión y producción lingüística (Lucas, 1998).

El rendimiento académico se caracteriza por ser multidimensional ya que en él intervienen distintas variables cuyo ordenamiento dentro de un modelo específico es difícil de alcanzar (Fullana, 1992). Usualmente, la valoración del rendimiento académico se da a través de simples evaluaciones que no consideran algunas dimensiones cognitivas básicas propias de un proceso sistemático. Las variables a considerar son de tipo: personal, escolar y social (Fullana, 1992). A lo largo de los años se han desarrollado distintos enfoques basados en la taxonomía de Bloom (Bloom & al., 1956), aproximación que en mayor o menor grado han llegado a los tres dominios psicológicos: el cognitivo, el afectivo y el psicomotor. Así también, se ha presenciado el desarrollo vertiginoso de la formación y evaluación por competencias, que sostiene la necesidad de desarrollar competencias genéricas o transversales y competencias específicas propias de cada área de estudio (Villa & Poblete, 2007), preparando al alumnado para «aprender a aprender» agregando sus capacidades dada la naturaleza cambiante de los tiempos modernos.

El rendimiento académico puede ser abordado desde distintas perspectivas, la efectividad es una de ellas y corresponde al nivel de éxito en el cumplimiento de los objetivos establecidos en los programas de estudio. Por lo tanto es una información importante para la toma de decisiones en las instituciones educativas. Es así, que en el estudio de Duart y otros (2008) se analiza un conjunto de universidades catalanas, considerando como indicador de aprobación la relación del número de créditos aprobados respecto al número de créditos matriculados, lo que determina que existan grupos de estudiantes con rendimiento académico alto, medio y bajo. Adicionalmente, se encontraron relaciones con variables como el género, la edad, el nivel socioeconómico, entre otras. En cuanto al género, en el nivel de rendimiento académico alto, las mujeres tienen una ventaja del 10% sobre los hombres. En relación a la edad, los jóvenes menores de 25 años obtienen mejores rendimientos.

Además de las variables que tradicionalmente se han relacionado con el rendimiento académico, ahora se suman las tecnológicas, que corresponden al entorno tecnológico institucional, las posibilidades de acceso y los usos de Internet; las mismas que son entendidas por Duart y otros (2008) como «nuevos determinantes del rendimiento académico», e inciden en el trabajo del estudiante a distintos niveles y de distintas formas. El entorno tecnológico de una institución educativa, si es utilizado en forma apropiada, constituye un factor importante para desarrollar una cultura de uso de tecnología. Si bien esto no garantiza un rendimiento académico determinado, puede conducir al estudiante a desarrollar buenas prácticas que aporten a la consecución de logros académicos. Duart y Lupiáñez-Villanueva (2005) encontraron tres ámbitos en los que la institución universitaria ha experimentado transformaciones; estos son: la infraestructura tecnológica, la innovación docente y los cambios organizativos. En el marco de estos tres ámbitos, los factores de mayor importancia cuando el estudiante se inicia en la cultura institucional son: por un lado, el nivel de tecnología como parte del modelo educativo y la necesidad de aplicarla en el desarrollo de la malla curricular y, por otro lado, el papel del docente que es el encargado de conducir al estudiante en la utilización de la tecnología y la información disponible, como medios y recursos de aprendizaje.

Diversos estudios relacionados con el uso de Internet determinan que se puede incidir positivamente en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes, mientras en otros casos ocurre el efecto contrario (Chen & Fu, 2009; Gil-Flores, 2009; Hunley & al., 2005; Luaran & al., 2011; Raines, 2012; Suhail & Bargees, 2006). Es así que para buscar relaciones con el rendimiento académico han utilizado las siguientes variables: actividades que el usuario realiza en línea, el tiempo de conexión a Internet y el contar con un computador y conexión desde el hogar. Sin embargo no se ha llegado a conclusiones determinantes, puesto que en otros estudios con condiciones similares, los resultados han sido contradictorios (Antonijevic, 2007; Azizi, 2014; Ellore & al., 2014; Junco, 2015). Así mismo, en otros casos el uso de tecnología presenta efectos positivos en ciertas áreas cognitivas del usuario como en el desarrollo de habilidades espaciales y de memoria, la mejora de las habilidades de lectura, escritura y de procesamiento de información, pero estas no necesariamente se traducen en mejoras en el rendimiento académico. Esto concuerda implícitamente con el concepto multidimensional de Fullana (1992), que requiere de formas multidimensionales de medición. Heyam (2014), después de hacer un meta-análisis acerca del uso de la tecnología y concretamente de las redes sociales sobre el desempeño de los estudiantes, divide las conclusiones en dos grupos. Por un lado facilitan la comunicación, socialización, coordinación, colaboración y entretenimiento; y por otro lado, se señala ser causante de adicción, desperdicio de tiempo, sobrecarga de información y aislamiento físico de la sociedad.

Otros estudios muestran relaciones entre el uso de tecnología y factores asociados al rendimiento académico. Uno de ellos es el de Gil-Flores (2009), que encontró una relación significativa entre el uso de computadores y el rendimiento académico. En este estudio se determinó que los estudiantes de secundaria que utilizan con mayor frecuencia el computador desde la casa, obtuvieron mayores calificaciones en matemáticas y comunicación lingüística. Hecho que sin señalar el uso de Internet como determinante, establece al menos una relación entre las variables; otro estudio con estudiantes de instituciones secundarias es el de Ndege y otros (2015) que señala efectos positivos y negativos del uso de la tecnología; como positivos encontró la mejora de las posibilidades de comunicación e interacción y como negativos el desperdicio de tiempo que conduce a una reducción del tiempo dedicado a actividades académicas.

En estudios con estudiantes universitarios Mishra y otros (2014) analizaron la relación del promedio de calificaciones de estudiantes universitarios y el tiempo dedicado a navegar en Internet. El resultado señaló una relación negativa significativa en la que a mayor tiempo en línea el promedio de calificación es menor. Adicionalmente en este estudio se encontró una relación significativa positiva entre la percepción del tiempo que pensaban que debían ocupar en sitios con información académica y el promedio de calificación. Türel y Toraman (2015) encontraron que los hombres tienden a tener mayor tiempo de conexión que las mujeres. Determinaron también que a medida que aumentan los promedios de calificaciones de los estudiantes considerados como exitosos se reducían los niveles de adicción a Internet. De manera particular el control debe centrarse en los estudiantes que utilizan Internet por más de tres horas al día. Lepp y otros (2015) analizaron el uso y la incidencia del uso del teléfono móvil y el promedio de calificaciones de estudiantes universitarios, encontrando que a mayor uso del teléfono el promedio era menor.

Chen & Fu (2009) concluyen que la búsqueda de información en la web mejora la calificación de los exámenes. En otros estudios con estudiantes de Pakistán, el uso de Internet tuvo efectos positivos en las calificaciones, en la mejora de las habilidades de lectura, escritura y procesamiento de información (Suhail & Bargees, 2006). Los recursos computacionales, como el uso de juegos de computadora, presentan efectos positivos sobre habilidades espaciales y de memoria, así como el desarrollo de las capacidades visuales, auditivas, estimulando el desarrollo de los estudiantes (Subrahmanyam & al., 2001). Un elemento que se presenta de forma recurrente en distintos estudios es la relación existente entre el rendimiento académico y el acceso a un computador en casa. Por el contrario, no se han podido establecer relaciones entre el uso de computadores en la institución educativa y el rendimiento académico (Gil-Flores, 2009). Existen otros aportes en la misma línea, donde indican que las personas que prefieren buscar información en la web, porque tienen acceso a una cantidad mayor de fuentes de información, y están informados acerca del contexto en el que la información se creó, tienen un mejor desempeño académico (Leung & Lee, 2012). Esto coincide con Kupczynski y otros (2011) quienes al analizar el comportamiento de estudiantes de cursos en línea encontraron que quienes son más activos (mayor número de sesiones) tienden a tener mejor rendimiento académico. En lo referente a la interacción, Castaño (2011) demuestra el beneficio de la interacción sobre el rendimiento académico destacando un mayor efecto en estudiantes de modalidad virtual que en presencial.

Considerando que las ciencias en general y las asignaturas en particular tienen distinta naturaleza y forma de ser abordadas, el uso de tecnología puede presentar incidencia positiva en ciertas áreas y negativa en otras. Así que en el estudio de Antonijevic (2007) se determina que el uso de computadores contribuye a un alto desempeño de los estudiantes en el área de ciencias y causa el efecto contrario en matemáticas. El uso de tecnologías en el aprendizaje afecta de manera directa al rendimiento escolar. Esto se puede evidenciar en el estudio de Wittwer y Senkbeil (2008), cuyos resultados no demuestran una relación entre el acceso al ordenador y su rendimiento en matemáticas. Sin embargo, sí se presenta un efecto positivo en los estudiantes que utilizaban el ordenador para resolver problemas. En cuanto al entretenimiento, existen diferencias marcadas de género en los adolescentes, las mujeres tienden a un uso social mientras que los hombres hacen un uso variado con énfasis en juegos en línea (Fernández, Peñalba, & Irazabal, 2015). Las personas que presentan adicción al uso de Internet presentan un rendimiento académico menor (Frangos, Frangos, & Kiohos, 2010). El puntaje que alcanzan los estudiantes tiende a ser menor conforme aumenta el tiempo que ocupan en juegos en línea (Ip, Jacobs & Watkins, 2008). Algo similar encontró Pepe (2011) con estudiantes de Primaria. Ocasionalmente se observan resultados contradictorios en donde la búsqueda de información ayuda a mejorar las calificaciones y las actividades de socialización y los juegos en línea tienen el efecto contrario (Chen & Fu, 2009). Hunley y otros (2005) encuentran que la cantidad de tiempo dedicado a Internet tiene una mínima relación con el logro académico de estudiantes de secundaria, sin embargo los puntajes de la prueba GPA no tienen relación con actividades específicas en línea como la búsqueda de información, uso del correo electrónico y videojuegos. La contradicción de los resultados de diversos estudios, evidencia la necesidad de mayor investigación, en la que se analice de forma sistémica el rendimiento académico y sus determinantes. Esto podría arrojar información importante respecto a usos beneficiosos de la tecnología en las actividades académicas y orientar el trabajo docente en cuanto al uso de tecnología.

2. Material y métodos

Se han establecido dos hipótesis referentes a que los usos de la tecnología tanto para fines académicos como para entretenimiento inciden positivamente sobre el éxito académico.

2.1. Población y muestra

La muestra fue seleccionada de cinco universidades presenciales de Ecuador entre febrero y mayo del 2015. Se encuestaron de forma aleatoria simple a 4.697 estudiantes. La distribución final de estudiantes cuenta con 48,5% de hombres y 51,5% de mujeres.

2.2. Instrumentos de recolección de información

Se desarrolló un instrumento basado en el cuestionario utilizado en el Proyecto Internet Cataluña (UOC, 2003) y a los que ofrece el proyecto Digital Literacy in Higher Education (DLINHE, 2011), adaptándolos a la realidad ecuatoriana y a las necesidades de esta investigación. En el cuestionario no se consultó a qué titulación pertenecían los alumnos. El cuestionario aplicado se divide en dos partes. En la primera parte se cuenta con 13 preguntas cuyas variables se detallan en la tabla 1, en el que se indagó acerca del uso de la tecnología para actividades académicas.

En la segunda parte se levantó información del uso de la tecnología para entretenimiento mediante las 10 variables que se presentan en la tabla 2. También se recabó información socio-demográfica utilizando las variables: edad, género y nivel de ingresos, los cuales fueron medidos en una escala ordinal de 5 niveles. Finalmente la información sobre el éxito académico a través de dos variables numéricas en las que se pregunta acerca del número de asignaturas en las que el estudiante se matriculó y el número de asignaturas que reprobó en el último semestre.

2.3. Procedimiento

Fue necesario crear una variable que representase el uso de Internet en actividades académicas y otra que representase el uso de Internet para entretenimiento. Para esto se clasificó a los estudiantes según el uso de la tecnología para fines académicos y para fines de entretenimiento. Para construir la variable «usos académicos» se utilizaron 13 preguntas que miden el uso de distintas herramientas tecnológicas en actividades académicas (tabla 1), aplicando sobre estas variables análisis factorial que permite reducir el número de variables agrupándolas en factores. Los factores calculados fueron: comunicación, participación y búsqueda, sobre los que se aplicó el método de análisis clúster k-medias. Para asegurar la persistencia de la clasificación obtenida los grupos se crearon calculando primero los centroides en base a una submuestra y a partir de estos se generaron los grupos. Los estudiantes se clasificaron en 2, 3, 4 y 5 grupos. De estos se escogió la que, según un análisis discriminante presentaba mayor exactitud y facilidad de interpretación de la estructura de los grupos. Para el análisis discriminante, se utilizó como variable dependiente el número de grupo generado en el análisis clúster y como variables independientes los factores provenientes del análisis factorial (Cea, 2005; Díaz-De-Rada, 1998; Shunglu & Sarkar, 1995), con lo que se determinó el porcentaje de elementos correctamente asignados en cada clasificación. Se procedió a seleccionar la clasificación en tres grupos que es la más fácil de interpretar. La clasificación final divide a los estudiantes en tres grupos cuyos centroides para cada variable se pueden observar en la figura 1.

Un procedimiento similar se aplicó para desarrollar la clasificación en base a los usos de Internet para entretenimiento. Las variables utilizadas y los factores resultantes del análisis factorial se pueden observar en la tabla 2. Las categorías finales de esta clasificación se presentan en la figura 2 (página siguiente).

También fue necesario crear una variable que represente al éxito académico, para esto se categorizó a los estudiantes en cuatro grupos según el número de asignaturas reprobadas o suspensas. Esto se consigue restando las asignaturas aprobadas de las asignaturas matriculadas (reprobadas o suspensas igual a asignaturas matriculadas, asignaturas aprobadas). Así se determinan cuatro categorías: no reprueba, reprueba una, reprueba dos y reprueba más de dos. Las correlaciones establecidas son, por un lado, los usos de Internet para actividades académicas y el éxito académico; y, por otro, los usos de Internet para entretenimiento y el éxito académico. Estas se obtuvieron utilizando modelos de regresión logística multinomial.

Figura 1. Grupos en función del uso de tecnología para actividades académicas.

3. Resultados

3.1. Categorización de estudiantes

La clasificación en base a los usos de Internet en actividades académicas divide a los estudiantes en tres grupos (figura 1). Estos grupos se denominan perfiles y son: el perfil académico dedicado cuenta con valores altos en todos los factores, especialmente en el denominado «Participación», que es su elemento distintivo y se refiere a las actividades interactivas y al trabajo con materiales educativos. La homogeneidad en los valores de este perfil dejan ver un uso balanceado de las herramientas de Internet, o lo que es lo mismo, los niveles de uso de las distintas herramientas es similar. En el factor «Comunicación» existe una semejanza entre el perfil académico buscador de información y el perfil dedicado. El perfil académico buscador de información presenta los valores más bajos en el factor «Participación» y tiene los valores más altos en el factor búsqueda de información. Su característica principal está dada por una contradicción, por un lado tiene un alto nivel de búsqueda de información y, por otro un bajo nivel de actividades interactivas y de trabajo con los materiales educativos, lo que denota un uso no balanceado de las herramientas de Internet. Finalmente, el perfil académico pasivo tiene los niveles de intensidad más bajos en búsqueda de información y en el uso de herramientas de la web social. En lo que se refiere a las actividades interactivas y trabajo con materiales educativos, los niveles de intensidad son bajos. Sin embargo, son superiores a los del perfil de buscador de información.

Figura 2. Grupos en función del uso de tecnología para actividades académicas.

La clasificación de estudiantes en base a los usos de Internet en actividades de entretenimiento los divide en tres grupos (figura 2). El primer grupo se denomina perfil de entretenimiento descargas, está conformado por el 32,4% de los estudiantes, y se caracteriza por tener el nivel más alto de descarga de programas, música, películas, contenido para radio y televisión. En este grupo la mayoría está conformada por hombres, alcanzando el 57,2%. El grupo 2 se denomina perfil de entretenimiento balanceado, esta denominación se debe a que este tipo de estudiantes hace un uso homogéneo de todas las posibilidades de entretenimiento; está conformado por el 19,8% de estudiantes y en su mayoría por hombres con un 58,3%. Las características distintivas de este usuario son el alto nivel de transacciones de compra y venta, así como también la preferencia por los juegos en línea. El grupo 3, denominado perfil de entretenimiento pasivo, abarca el 47,8% de los estudiantes, los que se caracterizan por tener el nivel más bajo en el uso de Internet en este tipo de actividades. Los estudiantes de este grupo son los de mayor edad y está conformado en su mayoría por mujeres, que alcanzan el 61,5%. Los bajos niveles de utilización de la tecnología delinean un perfil de estudiante para quien el entretenimiento es poco importante o no cuenta con posibilidades tecnológicas o de tiempo.

3.2. Usos académicos de Internet y éxito académico

Una de las hipótesis que se probaron en esta investigación sostiene que los usos de Internet en actividades académicas inciden positivamente sobre el rendimiento académico. El uso académico de la tecnología se agrupa bajo la denominación de perfiles, los que presentan diferencias entre sí. La principal diferencia es la existente entre el perfil dedicado y el perfil buscador de información, esta se da en el nivel de actividades de interacción y trabajo con los materiales educativos, que son altos en perfil dedicado y muy bajos en el perfil buscador de información.

La razón de probabilidad de reprobar o suspender una asignatura respecto a no reprobar ninguna disminuye 1,53 (1/0,65) veces cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil académico dedicado respecto al perfil académico buscador de información. La razón de probabilidad de reprobar una asignatura respecto a no reprobar ninguna aumenta 1,37 veces cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil académico pasivo respecto al perfil académico buscador de información. La razón de probabilidad de reprobar dos asignaturas respecto a no reprobar ninguna es 1,45 veces (1/0,68) menos cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil académico dedicado respecto al perfil académico buscador de información, es 1,48 veces mayor cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil académico pasivo respecto al buscador de información. La razón de probabilidad de reprobar tres o más asignaturas respecto a no reprobar ninguna es 1,33 (1/0,75) veces menor cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil académico dedicado respecto al perfil académico buscador de información, es 2,01 veces mayor cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil académico pasivo respecto al perfil académico buscador de información.

3.3. Entretenimiento y éxito académico

Otra de las hipótesis sostiene que el uso de Internet en actividades de entretenimiento incide sobre el rendimiento académico que alcanza el estudiante. Al respecto, un hallazgo muy importante es el que señala que los estudiantes que utilizan menos las posibilidades de entretenimiento tienden a suspender o reprobar más (tabla 4). Concretamente, la probabilidad de reprobar una asignatura respecto a no reprobar ninguna es 1,78 (1/0,55) veces menor cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil de entretenimiento descargas respecto al perfil pasivo; y es 1,29 (1/0,77) veces menor cuando el estudiante pertenece a perfil de entretenimiento balanceado respecto al perfil pasivo.

Algo similar ocurre cuando se analiza a quienes suspenden o reprueban dos asignaturas. La probabilidad de reprobar dos asignaturas respecto a no reprobar ninguna es 1,64 veces menor cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil de entretenimiento descargas respecto al perfil pasivo; y es 1,51 veces menor cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil de entretenimiento completo respecto al perfil pasivo. La probabilidad de reprobar más de dos asignaturas respecto a no reprobar ninguna es 2,06 veces menor cuando el estudiante pertenece al perfil de entretenimiento descargas respecto al perfil pasivo; y es 1,55 veces menor cuando el estudiante pertenece a perfil de entretenimiento completo respecto al perfil pasivo.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

A pesar de que la aplicación de tecnología en las actividades académicas determina solo un 3% del rendimiento académico, su efecto es visible dependiendo del tipo de uso. Los estudiantes que tienen mayor inclinación por interactuar y utilizar los materiales educativos (perfil dedicado), tienen menos probabilidad de reprobar o suspender que los estudiantes cuya actividad académica principal es buscar información (perfil buscador de información). Estos hallazgos difieren de los de Chen & Fu (2009) que sostienen que la búsqueda de información en Internet mejora el rendimiento académico. Las diferencias entre los perfiles dedicado y buscador de información, y su efecto sobre el rendimiento académico, coinciden con los postulados que señalan que la brecha digital no viene dada solamente por condiciones de acceso a la tecnología y conexión (Warschauer, 2002; Zillien & Hargittai, 2009) sino que influyen también el buen uso de esa tecnología y recursos, como es el caso del perfil dedicado cuya práctica se puede considerar balanceada y adecuada.

El perfil pasivo es el que presenta los niveles de uso de tecnología más bajos. Esto supone que el estudiante está condicionado por distintas restricciones (ingresos, conocimiento, conexiones) cuyo efecto negativo sobre el rendimiento académico es notorio, ya que quienes utilizan mínimamente las herramientas de Internet en actividades académicas (perfil pasivo) tienden a reprobar más que los estudiantes que basan su aprendizaje en la búsqueda de información (perfil buscador de información). Esto indica que la falta de acceso tiene un efecto negativo incluso mayor que el efecto de las malas prácticas o malos hábitos de uso de la tecnología. Así mismo, deja clara la desventaja de quienes tienen menos recursos, confirmando la teoría de brechas de conocimiento (Tichenor, Donohue, & Olien, 1970).

Se ha determinado que alcanzan mayor éxito académico tanto quienes hacen un uso balanceado de las distintas herramientas de Internet para su trabajo académico, como quienes muestran preferencia por las actividades interactivas y de trabajo con los materiales educativos, concordando con Castaño (2011) que señala los efectos positivos de la interacción. Por su parte, los estudiantes que utilizan Internet de forma pasiva tienden a obtener menores calificaciones.

La incidencia del uso de Internet sobre el rendimiento académico es significativo, esto concuerda con las conclusiones de Mishra y otros (2014), y Türel y Toraman (2015). Sin embargo, es necesario medir el tiempo de dedicación a estas actividades para determinar con mayor precisión la real incidencia que existe. En este sentido, a fin de optimizar la información a recoger, sería conveniente levantar la información de aquellas variables que en este trabajo han resultado más influyentes, como las relacionadas a la interacción y el trabajo con los materiales educativos. Un porcentaje importante (30%) de estudiantes utilizan Internet de manera exclusiva para buscar información y no para interactuar con sus profesores y compañeros o para utilizar los materiales del curso. Esto podría catalogarse como un comportamiento extraño y se requiere de información adicional que nos permita determinar si se trata de una práctica inapropiada o de nuevas metodologías ad hoc que se van estructurando de manera dinámica en la práctica tecnológica de los estudiantes.

El uso de Internet en actividades académicas no se ve afectado por el género. Tanto los hombres como las mujeres presentan los mismos patrones de uso de la tecnología.

En lo referente a las actividades relacionadas con el entretenimiento, contrariamente a los señalados por Ip y otros (2008) se ha encontrado una incidencia positiva del uso de Internet para entretenimiento sobre el rendimiento académico. Esta incidencia positiva no es clara por lo que se requiere de información adicional como por ejemplo el tiempo que los estudiantes dedican a cada actividad de entretenimiento. De manera general, los estudiantes que realizan descargas y quienes utilizan todas las posibilidades de entretenimiento presentan tendencia a reprobar menos que los estudiantes que no hacen uso o presentan un uso mínimo de Internet.

Ya sea el caso de suspender o reprobar una o más de dos asignaturas, los estudiantes del perfil descargas tienen mayores beneficios del uso de Internet en entretenimiento. Estos estudiantes tienen menos probabilidad de reprobar que aquellos que pertenecen al perfil completo, cuyo nivel de uso de la tecnología para entretenimiento es alto y balanceado. No se cuenta con datos que sustenten claramente este hallazgo. Sin embargo, al analizar las similitudes y diferencias entre los dos perfiles, la mayor diferencia se encuentra en el nivel de actividades comerciales de compra y venta, y juegos en línea. De estas actividades la que podría tener un efecto determinante es el nivel de juegos en línea (Ip & al., 2008), por lo que se extrajo el porcentaje de estudiantes que juegan en línea en cada perfil. Los estudiantes del perfil descargas juegan menos (53,5%) que los del perfil completo (87,7%). Esto podría explicar por qué el perfil completo tiene un éxito académico menor. Si bien este hallazgo resulta interesante, se requiere de evidencias más concluyentes. Lo que implica para trabajos futuros levantar variables adicionales como el tiempo que ocupa el estudiante en esta actividad.

En general, que los estudiantes que utilizan la tecnología para entretenimiento tiendan a tener mejor rendimiento académico va en contra de lo encontrado en distintos estudios (Frangos & al., 2010; Ip & al., 2008; Mishra & al., 2014; Pepe, 2011; Türel & Toraman, 2015). No se cuenta con datos que puedan explicar esto, más allá de que el nivel de incidencia del entretenimiento sobre el rendimiento académico alcanza el 1,9% de la varianza explicada.

Al comparar los estudiantes que hacen un uso de todas las posibilidades de entretenimiento (perfil balanceado) con los que lo hacen mínimamente (perfil pasivo), las mujeres tienen el doble de probabilidad de pertenecer al segundo grupo. Es decir, las mujeres tienden a utilizar menos la tecnología para entretenimiento. En cambio, al comparar los estudiantes del perfil balanceado con los estudiantes que realizan descargas, tanto los hombres como las mujeres se distribuyen entre los dos grupos sin presentar tendencias. Se puede concluir que el entretenimiento que prefieren las mujeres es la descarga de información en vez de los juegos en línea.

Referencias

Antonijevic, R. (2007). Usage of Computers and Calculators and Students’ Achievement: Results from TIMSS 2003. En International Conference on Informatics, Educational Technology and New Media in Education. Sombor, Serbia. (http://goo.gl/2zJ54R) (2015-03-18).

Azizi, E. (2014). Relationship between Internet Competency and Academic Achievement of Science Students in Bachelor Level. Research Journal of Recent Sciences, 3(9), 34-38. (http://goo.gl/oHBJZI) (2015-03-23).

Bloom, B., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I, The Cognitive Domain. New York: Adison-Wesly.

Castaño, J. (2011). El uso de Internet para la interacción en el aprendizaje: Un análisis de la eficacia y la igualdad en el sistema universitario catalán. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. (http://goo.gl/hZW1Rs) (2015-05-22).

Cea, M.A. (2005). La exteriorización de la xenofobia. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 112(5), 197-230. (https://goo.gl/B9TU43) (2015-02-28).

Chen, S.Y., & Fu, Y.C. (2009). Internet Use and Academic Achievement: Gender Differences in Early Adolescence. Adolecense, 44(176). (http://goo.gl/ZzkiOW) (2015-04-14).

Díaz-De-Rada, J.V. (1998). Diseño de tipologías de consumidores mediante la utilización conjunta del Análisis Cluster y otras técnicas multivariantes. Revista Española de Economía Agraria, 182, 75-104. (http://goo.gl/QNbNGG) (2015-03-23).

Dlinhe (2011). Digital Literacy in Higher Education. (https://goo.gl/dcQ4gj) (2015-02-17).

Duart, J. M., Gil, M., Puyol, M., & Castaño, J. (2008). La universidad en la sociedad Red. Barcelona: Ariel.

Duart, J.M., & Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F. (2005). E-strategies in the Introduction and Use of Information and Communication Technologies in the University. Universities and Knowledge Society Journal, 2(1). doi http://doi.org/10.7238/rusc.v2i1.243

Ellore, S.B., Niranjan, S., & Brown, U. (2014). The Influence of Internet Usage on Academic Performance and Face-to-Face Communication. Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science, 2(2), 163-186. (http://goo.gl/7En0YU) (2015-03-02).

Fernández, J., Peñalba, A., & Irazabal, I. (2015). Internet Use Habits and Risk Behaviours in Preadolescence. [Hábitos de uso y conductas de riesgo en Internet en la preadolescencia]. Comunicar, 44, 113-120. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C44-2015-12

Frangos, C., Frangos, C., & Kiohos, A. (2010). Internet Addiction among Greek University Students: Demographic Associations with the Phenomenon, Using the Greek Version of Young’s Internet Addiction Test. International Journal of Economic Sciences and Applied Research, 3(1), 49-74. (http://goo.gl/xr1RnX) (2015-03-05).

Fullana, J. (1992). Revisió de la recerca educativa sobre les variables explicatives del rendiment acadèmic: Apunt per a l’ús del criteri de 'modificabilitat pedagògica' de les variables. Estudi General, (12), 185-200. (http://goo.gl/ejXqcc) (2015-03-10).

Gil-Flores, J. (2009). Computer Use and Students' Academic Achievement. Research, Reflections and Innovations in Integrating ICT in Education (Internet). (http://goo.gl/ODCcGT) (2015-02-27).

Heyam, A. (2014). The Influence of Social Networks on Students' Performance. Journal of Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Sciences, 5(3), 200-205. http://doi.org/10.3916/C41-2013-19

Hunley, S., Evans, J., & al. (2005). Adolescent Computer Use and Academic Achievement. Adolecense, 40(158), 307-318. (http://goo.gl/2qPR7q) (2015-03-11).

Ip, B., Jacobs, G., & Watkins, A. (2008). Gaming Frequency and Academic Performance. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 24(4), 355-373. (http://goo.gl/7mO0M5) (2015-02-17).

Junco, R. (2015). Student class standing, Facebook Use, and Academic Performance. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 36, 18-29. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.001

Kupczynski, L., Gibson, A.M., Ice, P., Richardson, J., & Challoo, L. (2011). The Impact of Frequency on Achievement in Online Courses: A Study From a South Texas University. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 10(3), 141–149. (http://goo.gl/PNbNJT) (2015-02-03).

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2015). The Relationship between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students. SAGE Open, 5(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015573169

Leung, L., & Lee, P. (2012). Impact of Internet Literacy, Internet Addiction Symptoms, and Internet Activities on Academic Performance. Social Science Computer Review, 30(4), 403-418. doi: http://doi.org/10.1177/0894439311435217

Luaran, J. E., Binti, F., Mohd, K., & Nadzri, F. (2011). Hooked on the Internet:How does it Influence the Quality of Undergraduate Student’s Academic Performance? (http://goo.gl/67QNHr) (2015-02-20).

Lucas, M. L. (1998). Family Background, Home Environment and the Rate of Child Cognitive Development. Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Texas y Dallas.

Mishra, S., Draus, P., Goreva, N., Leone, G., & Caputo, D. (2014). The Impact of Internet Addiction on University Students and Its Effect on Subsequent Academic Success: a Survey Based Study. Issues in Information Systems, 15(I), 344-352. (http://goo.gl/H88TK3) (2015-03-30).

Ndege, W., Teresia, M., & al. (2015). Social Networks and Students’ Performance in Secondary Schools?: Lessons from an Open Learning Centre, Kenya. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(21), 171-178. (https://goo.gl/RpGBBd) (2015-03-26).

Pepe, K. (2011). A Study on the Playing of Computer Games, Class Success and Attitudes of Parents to Primary School Students. Educational Research and Reviews, 6(9), 657-663. (http://goo.gl/RR0u8i) (2015-04-16).

Raines, J. (2012). The Effect of Online Homework Due Dates on College Student Achievement in Elementary Algebra. Journal of Studies in Education, 2(3), 1-18. doi: http://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v2i3.1704

Shunglu, S., & Sarkar, M. (1995). Researching the Consumer. Marketing and Research, 23(2), 123-131. (https://goo.gl/ZPzpkt) (2015-03-30).

Subrahmanyam, K., Greenfield, P., Kraut, R., & Gross, E. (2001). The Impact of Computer Use on Children’s and Adolescents Development. Applied Developmental Psychology, 22(1), 7-30. (http://goo.gl/HRv5L) (2015-03-23).

Suhail, K., & Bargees, Z. (2006). Effects of Excessive Internet use on Undergraduate Students in Pakistan. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(3), 297-307. (http://goo.gl/fVV2aF) (2015-03-28).

Tichenor, P., Donohue, G., & Olien, C. (1970). Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge, Public Opinion Quarterly 34: . Public Opinion Quarterly, 34(2), 150-170. (http://goo.gl/MwCcJ0) (2014-04-10).

Türel, Y.K., & Toraman, M. (2015). The Relationship between Internet Addiction and Academic Success of Secondary School Students. Antropologist, 20, 280-288. (http://goo.gl/npyrwt) (2015-03-30).

UOC (Ed.) (2003). Internet Catalonia Project. (http://goo.gl/G3xmXT) (2015-04-20).

Villa, A., & Poblete, M. (2007). Aprendizaje basado en competencias una propuesta para la evaluación de las competencias genericas. Bilbao: Mensajero.

Warschauer, M. (2002). Reconceptualizing the Digital Divide. First Monday, 7(7). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v7i7.967

Wittwer, J., & Senkbeil, M. (2008). Is Students’ Computer Use at Home Related to their Mathematical Performance at School? Computers & Education, 50(4), 1.558-1.571. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.03.001

Zillien, N., & Hargittai, E. (2009). Digital Distinction: Status-Specific Types of Internet Usage. Social Science Quarterly, 90(2), 274-291. doi: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00617.x

Document information

Published on 30/06/16

Accepted on 30/06/16

Submitted on 30/06/16

Volume 24, Issue 2, 2016

DOI: 10.3916/C48-2016-06

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?