Summary

Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast (SCCB) is a rare disease, with a worldwide incidence <0.1%. In many cases, it is clinically characterized by rapid growth. Cyst formation due to central necrosis of the tumor accompanies its growth of the tumor in approximately 60–80% of all cases. Furthermore, it is considered difficult to diagnose SCCB solely on the basis of findings from diagnostic imaging. For large intracystic tumors, mammotome biopsy or core needle biopsy (CNB) is rarely performed. Instead, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) targeted at the tumor inside the cyst is often performed. The accurate diagnosis rate of SCCB using FNA is lower than that for ordinary-type breast cancer. If the cyst is large, the solid tumor shadow outside the cyst behind or around the cyst may be masked or hidden by the large cyst, which can sometimes yield an unclear view of the tumor shadow or make it impossible to visualize the shadow. In the present case, the contents within the cyst were completely aspirated and collected during the first step (FNA), thereby yielding a clearer, complete view of the solid tumor located outside the cyst. Thus, the subsequent step (CNB) was able to be performed in a more accurate and reliable manner. The combined use of FNA and CNB proved to be useful in making a preoperative diagnosis of SSCB accompanying a cyst.

Keywords

core needle biopsy;cyst;fine-needle aspiration;squamous cell carcinoma of the breast

1. Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast (SCCB) is a rare disease, with a worldwide incidence <0.1%.1; 2; 3; 4 ; 5 In many cases, SCCB is clinically characterized by rapid growth, and cyst formation due to central necrosis of the tumor accompanies this growth in approximately 60–80% of all cases.6 Accordingly, because of the presence of these cysts, mammotome and core needle biopsy (CNB) are rarely performed on large intracystic tumors, and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is often performed instead.7 However, FNA has a relatively poor sensitivity for SCCB, making its diagnosis difficult when using this technique.8; 9 ; 10 This report describes a case in which the combined use of FNA and CNB proved to be useful in making a preoperative diagnosis of SSCB accompanying a cyst.

2. Case report

A 47-year-old woman noticed a lump extending from the upper inner quadrant to the upper outer quadrant of her left breast 2 months earlier and visited the Takahashi Breast and Gastroenterology Clinic, Osaka, Japan. She had no appreciable medical history, but a review of her family history revealed that her mother had had breast cancer.

At presentation, a solid elastic tumor mass, approximately 4 cm in size, with a slightly unclear boundary and poor mobility, was palpable in the upper inner quadrant to the upper outer quadrant of the left breast. There was no continuity with the skin, fixation of the pectoral muscle, or abnormal secretion from the papilla, and no lymph nodes were palpable in the axillae.

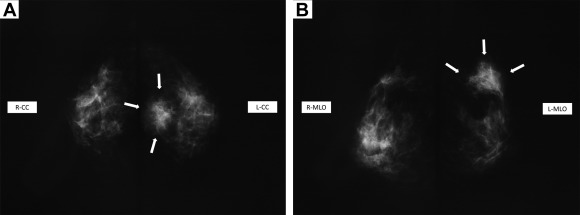

Mammography revealed a 3.8-cm mass shadow with an unclear boundary and irregular margin occupying a portion of both the upper inner quadrant and the upper outer quadrant. The presence of microcalcification led to the mass being classified as Category 4 (Fig. 1A and B).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Mammography. (A, B) Mammography reveals a 3.8-cm mass shadow with an unclear boundary and irregular margin occupying a portion of both the upper inner quadrant and the upper outer quadrant. The presence of microcalcification led to the mass being classified as category 4.

|

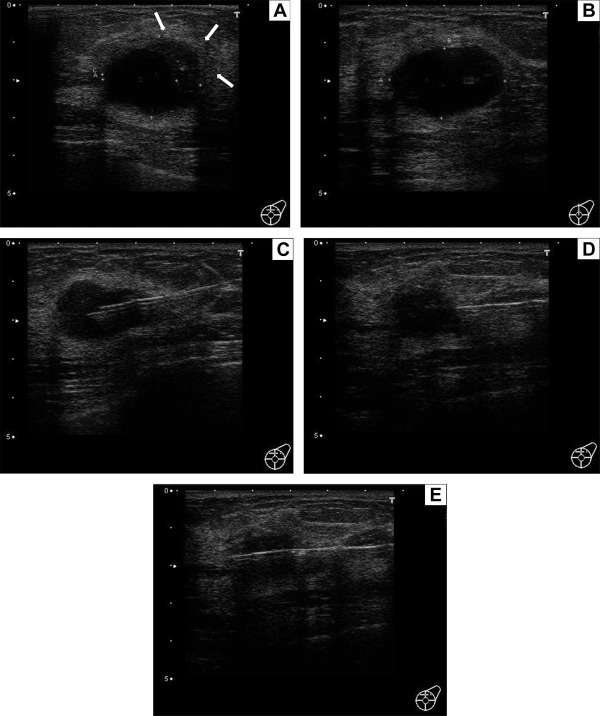

Subsequent breast ultrasonography showed part of a solid crescent-shaped tumor mass at the 12 o'clock to 3 o'clock position of the margin of the cyst shadow. This mass was 3.08 cm in size and was shown to be located in both the upper inner quadrant and the upper outer quadrant of the left breast, with bilateral shadows and enhanced posterior echoes (Fig. 2A). The cyst shadow alone was also visualized without the solid tumor when the direction and location of the beam were changed (Fig. 2B). Fig. 2C shows the FNA needle inserted in the cyst, and Fig. 2D is an image taken immediately after cyst aspiration, revealing a 2-cm shadow of the solid tumor, the overall image of which became clear at this point. In Fig. 2D, the line-shaped shadow running across from the right side to the front of the tumor is a CNB needle. The needle penetrated the solid component of the squamous cell carcinoma (SSC) more securely and accurately and was not blocked by the cyst (Fig. 2E).

|

|

|

Figure 2. Breast ultrasonography. (A) Part of a solid crescent-shaped tumor mass at the 12 o'clock to 3 o'clock position of the margin of the cyst shadow. This mass is 3.08 cm in size and is located in both the upper inner quadrant and the upper outer quadrant of the left breast, with bilateral shadows and enhanced posterior echoes. (B) The cyst shadow alone is also visualized without the solid tumor when the direction and location of the beam are changed. (C) The fine-needle aspiration (FNA) needle is inserted in the cyst. (D) An image taken immediately after cyst aspiration, revealing a 2-cm shadow of the solid tumor, the overall image of which became clear at this point. The line-shaped shadow running across from the right side to the front of the tumor is a core needle biopsy (CNB) needle. (E) The needle penetrated the solid tumor of the squamous cell carcinoma (SSC) tumor more securely and accurately and is not blocked by the cyst.

|

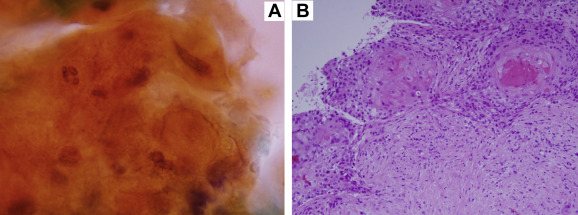

For pathological analysis of the FNA specimen, the cytoplasm was stained with orange G. Spindle-shaped nuclei and increased chromatin content were observed (Fig. 3A). On analysis of the CNB specimen, components of moderately differentiated SSC forming a cancer pearl were observed in the background of the interstitium, fibrosis in which resulted in ground glass opacity. There was no sign of glandular cavity formation (Fig. 3B).

|

|

|

Figure 3. Pathological analysis. (A) Analysis of the fine-needle aspiration (FNA) specimen; the cytoplasm is stained with orange G. It shows spindle-shaped nuclei and an increased chromatin content (Papanicolaou stain,×1000). (B) Analysis of the core needle biopsy (CNB) specimen; components of moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SSC) forming a cancer pearl are observed in the background of the glass-fibrosed interstitium. There is no sign of glandular cavity formation (hematoxylin–eosin stain, ×200).

|

On the basis of the preoperative diagnosis of SCCB, the patient was referred to another medical institution for surgery. Systemic examination was conducted, but no other signs of disease were found. The patient underwent partial mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy, and the pathological findings of the resected specimen were of SSC, infiltration diameter 34 mm × 26 mm, f, ly2, vo (high-grade nuclear atypia: 3, high-grade mitosis: 3), pN0: 0/1, ER: 1–5%, PgR: 0%, and HER2 score 1+.

3. Discussion

SCCB was first described by Troell in 1908.1; 11 ; 12 It is a very rare disease, with a worldwide incidence <0.1%,1; 2; 3; 4 ; 5 and the mean age of onset is reported to be 54 years.1 The General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Recording of Breast Cancer classifies SCCB as a special type of invasive cancer, defined histologically as “a cancer accompanying squamous metaplasia where cancer lesion is not only stratified but also cornified or has intercellular bridge”. In this patient, the tumor had no continuity with the skin and no abnormality was noted on systemic examination, leading to a diagnosis of primary SCCB. Although the precise histogenesis of primary SCCB remains unknown, it is thought to arise from the keratinous cyst of the breast, chronic abscesses, and squamous metaplasia of the lacteal gland.13 SCC is diagnosed when squamous cell components account for ≥ 90% of the tumor, with the remaining portion usually being composed of adenocarcinoma with squamous metaplasia.1; 14; 15 ; 16 In this patient, the tumor consisted almost entirely of SCC components and was therefore close to the pure type.

In many cases, SCCB is clinically characterized by rapid growth, and cyst formation due to central necrosis of the tumor accompanies this growth in approximately 60–80% of all cases.6 The lack of differentiation and rapid enlargement of tumors likely leads to central necrosis. Many SSCBs are progressive cancers and thus often have a poorer prognosis than more common types of breast cancer, with a mean 5-year survival rate of only 50–63%.16 Although distant metastasis occurs frequently, lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and indeed, 70–80% of primary SCCBs have no lymph node metastasis.2; 15 ; 17

Previous studies on SCC imaging suggest that mammography generally does not reveal malignant findings, such as spiculas and microcalcification,1; 4; 8; 17 ; 18 whereas ultrasonography often generates cyst images. However, no consistent ultrasonographic characteristics except the cyst formation have been described for the SCC.1

Because of the absence of characteristic imaging findings, it is considered difficult to diagnose SCCB using these modalities.1; 6; 8; 9 ; 19 As for intracystic papillary lesion compared with SCC, microlobulated margin is the dominant margin characteristics and is suggested as the common feature of all papillary lesions regardless of whether it is benign or malignant.20

Primary SCCB is treated by surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy, depending on the disease stage, although it often shows a refractory course. Endocrine therapy is often not successful as most tumors are negative for hormone receptors,1; 2; 5; 6; 17 ; 21 as was the case for this patient.

Systemic therapy for preoperative progressive breast cancer is usually centered on chemotherapy; however, SCCB has been found to be resistant to the chemotherapy regimen used for more common types of breast cancer and follows a rapid aggressive course.3; 17 ; 22 It has been suggested that surgery should be prioritized over chemotherapy as the initial treatment for this disease,16 ; 17 and consequently, it is preferable to diagnose SCC preoperatively.

For large intracystic tumors, mammotome biopsy or CNB is rarely performed. Instead, FNA targeted at the tumor inside the cyst is often performed. The accurate diagnosis rate of SCCB using FNA is lower than that for ordinary-type breast cancer.6; 8; 9; 10 ; 19 It is therefore considered difficult to preoperatively diagnose SCCB by FNA alone, and surgical resection is therefore necessary.1; 6; 14; 15 ; 22 Because only adenocarcinoma cells are partly sampled or the intracystic component is sampled in cystic carcinoma, accurate diagnosis becomes difficult.

If the cyst is large, the solid tumor shadow outside the cyst behind or around the cyst may be masked or hidden by the large cyst, which can sometimes yield an unclear view of the tumor shadow or make it impossible to visualize the shadow. In the present case of cystic carcinoma, the contents within the cyst were completely aspirated and collected during the first step (FNA), thereby yielding a clearer, complete view of the solid tumor. Consequently, CNB for the solid tumor could be accurately and safely performed. It is suggested that the combined use of FNA and CNB is useful in making a preoperative diagnosis of cystic-type SCCB.

4. Conclusion

The combined use of FNA and CNB in this very rare case of cystic-type SCCB proved to be useful in making a preoperative diagnosis.

In cases in which a large shadow of a cyst is noted, it is necessary to carefully observe not only the inside of the cyst but also its surroundings including its background in order to ensure that it is not obscuring a solid tumor such as SCC.

Furthermore, FNA should be proactively performed in cases of a large cyst shadow when any abnormality is noted outside the cyst.

References

- 1 J. Grabowski, S.L. Saltzstein, S. Sadler, S. Blair; Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast: a review of 177 cases; Am Surg, 10 (2009), pp. 914–917

- 2 T. Menes, J. Schachter, S. Morgenstern, E. Fenig, H. Lurie, H. Gutman; Squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) of the breast; Am J Clin Oncol, 26 (2003), pp. 571–573

- 3 L. Bhatt, I. Fernando; Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast: achieving long-term control with cisplatin-based chemotherapy; Clin Breast Cancer, 9 (2009), pp. 187–188

- 4 V.J. Nair, V. Kaushal, R. Atri; Pure squamous cell carcinoma of the breast presenting as a pyogenic abscess: a case report; Clin Breast Cancer, 7 (2007), pp. 713–715

- 5 E.R. Fisher, R.M. Gregorio, B. Fisher; The pathology of invasive breast cancer: a syllabus derived from the findings of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (Protocol No 4); Cancer, 36 (1975), pp. 1–85

- 6 M. Honda, S. Saji, S. Horiguchi, E. Suzuki, T. Aruga, K. Horiguchi; Clinicopathological analysis of ten patients with metaplastic squamous cell carcinoma of the breast; Surg Today, 41 (2011), pp. 328–332

- 7 K. Naito, S. Oura, T. Yoshimasu, et al.; A case of squamous cell carcinoma of the breast showing a giant intracystic tumor; J Wakayama Med Soc, 59 (2008), pp. 109–111 [In Japanese]

- 8 S. Hasegawa, Y. Takatsuka, K. Yamazaki, H. Morino; Four cases of primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast; Jpn J Breast Cancer, 14 (1999), pp. 73–77 [In Japanese]

- 9 H. Inutsuka, K. Anan, F. Katsumoto, K. Tamae, S. Mitsuyama; Preoperative diagnosis in nine cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the breast; J Jpn Surg Assoc, 62 (2001), pp. 2145–2150 [In Japanese]

- 10 Y. Shibata, K. Satoh, M. Kodama, H. Nanjyo; A case of squamous cell carcinoma of the breast; Jpn J Breast Cancer, 23 (2008), pp. 425–428

- 11 A. Troell; Zwei Fälle von Palttenepithelcarcinom. Der Brustdrüse; Nord Med Arkiv (1908) Afd.I. (Kirurgi).Häft.1.N:r S.:1–11. [In German]

- 12 N.S. Salemis; Breast abscess as the initial manifestation of primary pure Squamous cell carcinoma: a rare presentation and literature review; Breast Dis, 33 (2011/2012), pp. 125–131

- 13 J. Vera-Alvarez, M.D. García-Prats, M. Marigil-Gómez, M. Abascal-Agorreta, J.I. López-López, J.M. Ramón-Cajal; Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology: a case study using liquid-based cytology; Diagn Cytopathol, 35 (2007), pp. 429–432

- 14 P.P. Rosen; Rosens Breast Pathology; Lippincott Raven, Philadelphia, PA (1996)

- 15 I. Aparicio, A. Martínez, G. Hernández, D. Hardisson, J. De Santiago; Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast; Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 137 (2008), pp. 222–226

- 16 F. Cardoso, C. Leal, A. Meira, et al.; Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast; Breast, 9 (2000), pp. 315–319

- 17 R. Shigenaga, K. Enokido, M. Ikeda, et al.; A case of rapidly growing squamous cell carcinoma of breast; Jpn J Breast Cancer, 27 (2012), pp. 83–88 [In Japanese]

- 18 J. Tashjian, C.C. Kuni, L.E. Bohn; Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast: mammographic findings; Can Assoc Radiol J, 40 (1989), pp. 228–229

- 19 K. Sakurai, H. Okamura, K. Enomoto, et al.; Two cases of primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast; J Nihon Univ Med Assoc, 62 (2003), pp. 673–676 [In Japanese]

- 20 T. Al Hassan, P. Delli Fraine, M. El-Khoury, L. Joseph, J. Zheng, B. Mesurolle; Accuracy of percutaneous core needle biopsy in diagnosing papillary breast lesions and potential impact of sonographic features on their management; J Clin Ultrasound, 41 (2013), pp. 1–9

- 21 B.H. Woodard, A.D. Brinkhous, K.S. McCarty Jr.; Adenosquamous differentiation in mammary carcinoma: an ultrastructural and steroid receptor study; Arch Pathol Lab Med, 104 (1980), pp. 130–133

- 22 N. Uchida, K. Ishiguro, T. Suda, M. Nishimura; A case of aggressive primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast refractory to preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy; Jpn J Cancer Chemother, 36 (2009), pp. 2619–2622 [In Japanese]

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?