Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This study examines the transformation of classroom dynamics brought about by the use of tablets for educational purposes. The empirical bases of this study were defined by the “Samsung Smart School” project, which was developed by Samsung and Spain’s Ministry of Education during academic year 2014-15, in which teachers and 5th and 6th year students attending 15 primary schools across several Autonomous Communities in Spain were provided with tablets. The research sample comprised 166 teachers. A qualitative analysis strategy was applied by means of: a) non-participant observation, b) focus groups, c) semi-structured interviews with teachers, and d) content analysis of teaching units. These techniques enabled us to extract and examine six dimensions of teaching (educational objective, teaching approach, organization of content and activities, teaching resources, space and time, and learning assessment). Our findings show that teachers tend to apply a transversal approach when using tablets to work on different competencies, focusing more on activities than on content through the use of apps. They reclaim the act of play as part of the learning process, and tablet use encourages project-based learning. To sum up, this study shows that teachers view tablets not only as a technological challenge, but also as an opportunity to rethink their traditional teaching models.

1. Introduction and state of the question

The use of mobile devices in the classroom is currently a subject of keen interest for the teaching community (Johnson, Adams-Becker, Estrada, & Freeman, 2014), not only for the huge potential they offer for enriching the educational process (Traxler & Wishart, 2011) but also for their broad acceptance, accessibility and the educational expectations they generate (Maich & Hall, 2016). This recognition is not just a question of the increasingly sophisticated nature of these technological devices in terms of their use in education (Kanematsu & Barry, 2016), but also due to factors such as: the increase in sales of mobile devices over personal computers, the exponential development of educational devices, the potential to access educational resources or the experience of ubiquitous anytime connection that opens up new paths for education and learning (Haßler, Major & Hennessy, 2015; Kim & Frick, 2011).

The huge increase in the use of personal devices at home and school poses important questions concerning their usage and role in the development and process of learning (Chiong & Shuler, 2010, Crescenzi & Grané, 2016; Price, Jewitt, & Crescenzi, 2015; Ruíz & Belmonte, 2014). The presence of these devices in students’ everyday lives means that we can now talk in terms of some serious emerging educational alternatives, with technology such as BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) (Arias-Ortiz & Cristia, 2014) or “the flipped classroom” (Davies, Dean, & Ball, 2013). The potential is even greater when you find the same, or even more, technology at home than at school (Mascheroni & Kjartan, 2014).

However, although the advantages of using mobile devices in the classroom seem evident, the “positive impact” of their emergence in formal education is by no means overwhelming. Several studies show that their use in the classroom improves the quality of education as opposed to traditional learning methods, while others do not find sufficient empirical evidence to justify such positive claims. In this sense, Nguyen, Barton and Nguyen (2015) show that although the use of tablets in the educational context enhances the learning experience, it does not necessarily lead to improvements in performance. Similar studies coincide with works by Leung and Zhang (2016) and Dhir, Gahwaji and Nyman (2013), who point out that while tablet use can stimulate motivation towards learning, its real impact is limited. Instead, motivation to learn is based on challenge, curiosity, cooperation and competitiveness rather than the use of these devices in the classroom (Ciampa, 2014).

Studies on the use of tablets in education tend to report on what works and what does not, or on the scenarios and conditions that must be in place for technology and “mobile learning” to function in class. In other words, they provide good practice models that aim to act as a teacher toolkit on the subject. The question posed by educational studies on tablet use should not be about whether these devices are effective or not, but how they can be deployed in the classroom and whether their use continues to be conditioned by traditional pedagogical or text book-based models (Marés, 2012).

Apart from academic performance, tablets can also enhance the learning experience in the classroom. For example, Kucirkova (2014) shows that the academic value of a tablet depends on the features of the apps and how their content can influence participation in the classroom. Likewise, Falloon (2013) shows how app design and content are crucial for learning in a productive and motivating setting, as demonstrated by the author with an effective intervention programme based on a careful selection of apps for the classroom. Falloon (2015) also shows that tablet usage in the classroom can consistently broaden students’ learning provided there is a carefully designed itinerary based on collaboration, debate and negotiation, and sufficient role changing when group work is undertaken. This type of study, like the work we present here, insists on the pedagogical rather than the technological component (Flewitt, Messer, & Kucirkova, 2015).

According to Ciampa (2014), academic research into tablet use in the classroom should focus on the pedagogical benefits, the device’s potential for self-directed learning, personalization of the device, team work, increasing and improving communication and collaboration, reinforcing autonomous learning, students’ commitment and motivation, the potential for individualized learning (personalized), more effective special needs teaching and the creation of interactive classroom environments (Kim & Jang, 2015). All this forms part of the “pedagogical culture” surrounding technology, and tablets, that all teachers need to develop (Freire, 2015).

So, the use of technology in general, and tablets in particular, should adhere to the premise that pedagogy involves technology, not the reverse (Hennessy & London, 2013). Without an alternative pedagogical model based on good practices, mobile devices amount to no more than a sophisticated resource in the teaching and learning process, one more piece of academic furniture (Suárez-Guerrero, 2014). So, the objective of our study is to understand and characterize the pedagogical model designed to promote the educational use of tablets in the classroom rather than determine if there is a causal link between tablet use and improved academic performance. Our work is aligned to Botha and Herselman (2015) in terms of understanding the process of integrating tablets as one part of the technological and pedagogical ecosystem.

To discover teachers’ perceptions of the digital transformation of the classroom via the educational use of tablets, we analysed the “Samsung Smart School” project set up by Samsung Electronics Iberia, in collaboration with Spain’s Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, and several of the country’s Autonomous Communities involved in the project. The project analysed the educational changes that occurred in classroom dynamics as a result of the implementation of the “Samsung Smart School” in Spain in academic year 2014-15. The project encouraged the use of tablets in 5th– and 6th-year primary schools students in the Autonomous Communities of Aragón, Asturias, Canarias, Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Extremadura, Galicia, Islas Baleares, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia, Navarra, and the Autonomous Cities of Ceuta and Melilla.

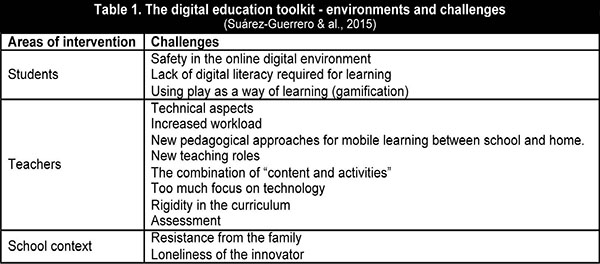

Given that understanding the process by which teachers appropriate the technology is fundamental to identifying the challenges of technology in education, and in order to help teachers manage this process, the study we made also led us to design a Digital Education Toolkit for just such users. The toolkit provides 13 structured didactic recommendations covering three major areas of intervention (table 1) so that teachers in general, and those teachers involved in the “Samsung Smart School” in particular, can learn how to manage tablets better from an educational perspective (Suárez-Guerrero, Lloret-Catalá, & Mengual-Andrés, 2015). This article describes the research process and the results on which the toolkit is based.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Aim of the study

The aim of this was to discover the pedagogical changes that occurred in the classroom as a result of the use of the tablet, based on teachers’ activities and perspectives, within the framework of the “Samsung Smart School” project in Spain in academic year 2014-15. For this project Spain’s Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, through the National Institute of Educational Technologies and Teacher Training (INTEF), and the educational authorities in Spain’s Autonomous Communities and Samsung selected one primary school centre from each of the participating Autonomous Communities and from the Autonomous Cities of Ceuta and Melilla, based on the following criteria: a) schools in remote rural areas, b) areas with high school drop-out rates, c) areas with high levels of unemployment, d) Special Education centres.

2.2. Design

This research applied a qualitative approach based on Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2009) and aimed to study the educational uses of tablets in primary school settings through six pedagogical dimensions:

• Educational Objective: Which competences does the teacher aim to develop in the classroom with tablets?

• Teaching approach: Which approach for student learning does the teacher apply in the use of tablets in the classroom?

• Content and activities: What content does the teacher use and how does he/she develop it with the tablet?

• Teaching resources: What materials does the teacher use to develop learning through tablets?

• Space and time: How do tablets transform education in the classroom and how does the teacher manage time?

• Learning assessment: How are tablets used to evaluate students’ learning?

We studied these dimensions by applying four qualitative data-gathering techniques: a) non-participant observation, b) focus groups, c) virtual interviews, d) analysis of the content of the project’s teaching units.

2.3. Participants and procedure

The study population consisted of 166 teachers and 766 students from 15 primary education centres. Of the teachers, 29.8% were men and 67.5% women, and their average age was 40.5 years. Among the students, 44.5% were girls and 55.5% were boys, aged between 10 and 11.

Firstly, we carried out a non-participant observation in four of the primary education centres involved in the project, in the provinces of Zaragoza, Guadalajara, Madrid and Murcia. These specific units were chosen by random sample. Three observers were responsible for developing this phase of the project. A check table was used to monitor the behaviour of the teachers and students related to the analysis of the dimensions proposed. A total of 12 check lists were formulated for subsequent treatment and analysis.

Secondly, focus groups were set up, and in order for all the centres to be represented, two focus groups were established, each holding a parallel two-hour session, one that consisted of teachers (n=7) and ambassadors –teachers who acted as project coordinators– at the project centres (n=8). The participants were selected by a cluster sampling procedure. The structure of the dynamic dealt with: a) habits, the relation to, and effect of, the use of tablets on students’ attitudes; b) a SWOT analysis of classwork using technology; c) assessment of the “Samsung Smart School” project experience: perceptions, its potential and suitability for profiles/centres, optimization, and recommendations for implementation. The advantage of small-scale focus groups is that each participant’s voice and opinion is heard (Wibeck, Dahlgren, & Oberg, 2007); it is also a common technique for gathering qualitative information in educational research (Puchta & Potter, 2004). Both sessions took place at the same time in two observation rooms with one-way mirrors, and were directed by two expert researchers who had been trained to prevent any deviation from the dimensions of the study. The project researchers had contact with session directors, and they monitored the sessions for later treatment and analysis.

The project also developed 13 virtual interviews consisting of at least one teacher/ambassador in each of the project centres. Using a semi-structured script of 10 open questions based on the six study dimensions, the 30-minute interviews –developed via Adobe Connect– gathered the perceptions of the interviewee on his/her experience of the integration of the technology in the classroom, the difficulties encountered and the recommendations and solutions they saw as feasible for other teachers in order to optimize the “Samsung Smart School” project. The 13 interviews were videoed for later treatment and analysis.

Finally, a qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2000) was carried out on 80 teaching units used by the centres in the programme. The aim of this analysis was to understand the planning behind the teaching and learning process with tablets, as well as to detect good practices in the design of curricula with technology.

2.4. Data gathering and analysis

The data for this study were collected between December 2015 and May 2015. The interviews were videoed for subsequent analysis, with prior authorization from the interviewees. Data on the non-participant observations and focus groups were recorded manually while the teaching units were processed in RTF format. The content of the recordings, the observations, interviews and the teaching units were stored, processed and analysed, always with the utmost respect for the anonymity of the participants. The transcripts of the focus groups, interviews and non-participant observations generated a huge amount of information, so the approach of the analysis in terms of the study objectives helped us to manage these data (Krueger & Casey, 2014). The data gathered by the instruments were processed and analysed using Atlas.ti 7 software, enabling us to analyse the content of the video recordings without the need to transcribe them. Likewise, the use of RTF and PDR files saved time on transcription and analysis.

Content analysis is a research technique suitable for formulating valid reproducible inferences from particular information that can be understood within the study context (Krippendorff, 1990). So, we performed a mixed (deductive and inductive) coding process based on the six dimensions of the study, which gave us an emergent coding (Strauss, 1987). By means of a qualitative analysis estimation –inferring relations rather than generating hypotheses– (Krippendorff, 1990), we ran an individual thematic analysis of the data by reading, codifying, recodifying, family assignation and data categorization –framed by the study dimensions- (Braun & Clarke, 2013). The themes generated were reviewed by the authors together in order to reach common agreement on the findings. The validity of the method used in this research is, therefore, rooted in compliance with the criteria described by Cresswell and Miller (2000): a) triangulation with data and researchers; b) reviewing with the members of the research team.

3. Analysis and results

Here we present the results of the analysis of the non-participant observations, the interviews, focus groups and analysis of the content of the teaching units organized around the six dimensions of the study:

3.1. Educational objective

In the teaching units generated within the project framework, the content analysis and observations reveal a clear trend towards developing learning activities with tablets that integrate the key competences in the various curricular areas. Nevertheless, the analysis of the teaching units shows a marked emphasis on developing the linguistic communication and digital competences. In contrast, mathematics and basic competences in science and technology receive least attention. It is worth noting that the very nature of the “Samsung Smart School” project enabled teachers to develop digital competence to an extent that had not been possible before due to limited access or family financial constraints: “If it weren’t for the project, we could not have stimulated the development of the digital competence” (interview 7).

Furthermore, the interviews and focus groups showed that the teachers on the project saw the use of tablets in terms of learning activities related to the search for, and selection, organization and use of information, either individually or in groups. They also agreed that the educational use of tablets connected to Internet generated different expectations in the students in terms of information sources.

3.2. Teaching approach

The teachers in the interviews and focus groups insisted that tablets in the classroom could only be used effectively if there was a change in methodology, and that such a change must lead to the adoption of active methodologies like Project-Based Learning (PBL) and collaborative learning.

The participants also pointed out that when no pedagogy exists to exploit their educational potential, tablets amount to no more than a sophisticated reproducer of monotonous tasks. For example, one teacher from the ambassadors’ focus group commented that “if you have no pedagogy, then tablets won’t work in the classroom”. And this pedagogy is not necessarily about improving teaching in the classroom but understanding the new activities that students are capable of doing when they use tablets in their learning, either as individual learners or in groups. This means that although PBL and collaborative learning are distinctive features of the project, there are also other pedagogical challenges that can be exploited to get the most out tablets in the classroom.

3.3. Content and learning activities

The interviews and focus groups showed that teachers now view the tablet as a notebook for students to manage their own learning in digital form. Beyond reading and writing, this “new notebook” can stimulate other activities such as investigation or multimedia-based tasks. So, for many teachers on the project, the main function of the classroom tablet is not to provide content, as if it were a book, but to enable students to get involved in, and develop, new types of activities and manage their own learning. One teacher put it like this: “After using a tablet, a class given in the traditional format no longer interests them…teachers must now reinvent their educational activities” (interview 11).

The analysis of the content of the teaching units revealed that two thirds of these units clearly aim to stimulate collaborative use of the tablet among students. In the main, they direct students towards enquiry and dialogue rather than individual work and competition between students. Little of the content analysed attempts to limit tablet usage to the development of one single type of curricular content.

The interviews and focus groups show how teachers now recognize that they are no longer the single source of information, and that the students are now an active component of classwork. Data also show that teachers recognize the considerable creative potential of tablets in the classroom, for example in editing documents, making presentations, scheduling a radio programme, online investigation, book design and editing photos and videos. And these are tasks that can be developed individually and in collaboration thanks to tablet technology.

3.4. Teaching resources

Data show a trend among the teachers to use apps that are not necessarily linked to specific content but which are generic in nature and allow students to perform a variety of learning activities across a spectrum of subject areas. The most popular are “sound and image treatment” apps that enable the students to create and design content (the camera, Tellagami, Aurasma, audio and video editor, etc.), and apps for communication and information browsing. The analysis of the didactic units demonstrated that the teachers use these apps to create activities: “Tablets can help us create learning activities, not just searching for information, which is the function of the book” (interview 4).

Yet the tablet is not the only resource in the classroom. The analysis of the teaching units and the visits to the centres showed how teachers use the tablet for teaching via the TV screen or the interactive digital whiteboard (PDI), if the centre had one, as well as by laptop/PC, and even cell phone. The teachers used tablets in different ways in the classroom, and opinions on their use varied. For example, the interviews revealed how some teachers thought that tablets were more versatile in fomenting the classroom dynamic than the laptop, and others said that PDIs were technological devices that reproduce traditional pedagogical models as opposed to tablets which clearly reinforce group work.

Another useful complement for teachers in class is the digital pencil S Pen, often used in conjunction with the S Note app. The teaching units’ analysis showed that teachers made extensive use of the S Pen in activities involving writing by hand from note taking to drawing, which added value to the teaching in the classroom.

An important aspect that came up in the observations and focus groups was how the teachers saw that tablet as a tool for personalizing learning. In contrast to the conventional blackboard or PDI, which the teachers associated to the dissemination of content towards the class, the tablet represents an important advance in giving students individual attention and monitoring their work more closely. However, the teachers pointed out that to make this work successfully, more time would be needed to plan and develop activities for use on the tablet.

Another positive aspect for teachers is sustainability, which saves on photocopying, but also throws up a new problem in technological incompatibility between operating systems, web apps and files.

3.5. Space and time

The observations, interviews and focus groups noted the teachers’ remarks on the fact that the students are also aware of the changes that have taken place in the classroom, not just due to the physical presence of technology but also for the change in the type of learning activities, the role of the teacher and student, as well as the physical reorganization of the classroom. In the focus group one teacher said: “The students are no longer sat in rows looking at other students’ backs. Classes are now mobile”.

The classroom is no longer a rigid environment with students lined up in rows listening to a teacher but an open flexible space endowed with a different dynamic in which everyone can stand up, walk around and talk to everybody else, and all this thanks to the tablet. Yet the analysis of the teaching units also showed how the teachers rarely used the tablet to move out of the classroom and occupy another area and transform it into an educational space.

The project teachers’ opinions varied in terms of the time students need to be able to work autonomously with a tablet. There was no agreement on a definitive average time required for students to be tablet self-sufficient, as the responses to this question showed, because students’ previous experience with technology and the frequency of tablet use in the classroom were important unquantifiable factors. However, all teachers insisted that the students needed to be given time to manage the device independently and to evolve from using the tablet as a toy to using it as a learning tool.

3.6. Assessing student learning

Although from the visits, interviews and focus groups we learned that some teachers feel that assessment “is the big unresolved issue”, most of the project participants cited four changes in the way students are assessed: assessment as a game, the introduction of rubrics, the immediacy of feedback and the use of online multiple choice assessment. The tools most widely used in this respect are Socrative, Kahoot, Rubistar or Google questionnaires. Analysing the teaching units helped us to see how traditional forms of assessment mixed easily with alternatives such as joint-assessment, self-assessment or even the opportunity to personalize learning. As one focus group member said: “The tablet gives you more flexibility; you can design material specifically for one particular student”.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study forms part of an emergent line of investigation in education, digital pedagogy. This pedagogy is under construction, and is fundamentally centred on assessing educational models that use technology in the classroom, and on detecting its potential use, the challenges it represents and trends in other educational spaces (Boling & Smith, 2014; Chai, Koh, & Tsai, 2013, Gros, 2015; Harris, 2013). This line of investigation, as this present research, is not about technology in itself but aims to know what technology can actually do in the classroom (Flewitt, Messer, & Kucirkova, 2015).

However, we must point out that this study was carried out in optimum technological conditions since, thanks to the “Samsung Smart School” project, teachers and students each had access to a tablet and an Internet connection. So, these pedagogical findings should be measured against settings and situations in which technology access for all students and teachers is not an issue.

The content analysis of the data generated by the four qualitative techniques enables us to infer (Braun & Clarke, 2013) that the project teachers face the challenge of the table not just from a technological perspective but also construct a pedagogical vision of its use in education (Butcher, 2016). Configuring the tablet with this pedagogical vision, as shown in the categorization of the six dimensions studied, is evident in the teachers’ activity with, and perception and programming of, the tablets.

And despite what one might think, the project teachers’ pedagogical vision of the tablet is evident not only in answer to the question “what tool do I use to learn?”, which is associated to the apps in this study, but also in the definition of the educational objective, the conception of the didactics, the development of activities, the representation of educational space and time, and in the assessment of learning. As the results show, technology opens up a wide range of new educational functions that the teacher assumes as part of his/her curricular activity. This seems to be the trend in terms of the educational value of the new conditions generated by mobile devices for learning (Traxler & Kukulska-Hulme, 2016).

In terms of the main educational functions the Internet-connected tablet offers the primary school classroom dynamic, the project teachers recognize that although the most widely worked competences are linguistic communication and digital competence, the tablet enables them to work with various other competences transversally, and that the use of this device for educational purposes involves a change in teaching methodology that fits neatly with the development of Project-Based Learning and collaborative learning. Of course, tablets provide access to information but its main didactic use is not to contribute specific content but, thanks to the generic apps it contains, to develop a wide range of activities that evolve from information consumption to production, and which implies the development of a digital competence that is directly linked to multimedia language. And, the use of tablets can open up a rich seam for personalizing learning and joint-assessment (Botha & Herselman, 2015)

As the interviews and focus groups have shown, it is essential to understand that tablets presage –which does not mean to say that they cause– a series of transitions: the evolution of the tablet from toy to learning tool, from pedagogies of information consumption to pedagogies of creation, from static pedagogies to mobile pedagogies, from the potential of the text book to that of the digital notebook, from content to activities, from managing achievements to managing errors, and the biggest jump, from the image of technology as a neutral tool to one that stimulates change in standard classroom culture.

Changes in education are not just about the use of the tablet in the classroom, rather it is the symbolic tool that teachers can use to think about all the pedagogical elements that range from new functions to transitions that demand going beyond the mere replacement of the old with the new.

Support and acknowledgements

This study was carried out thanks to the support of Samsung Electronics Iberia, and the collaboration of Spain’s Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, and the Autonomous Communities that participated in the project.

References

Arias-Ortiz, E., & Cristia, J. (2014). El BID y la tecnología para mejorar el aprendizaje: ¿Cómo promover programas efectivos? IDB Technical Note (Social Sector. Education Division), IDB-TN-670. (http://goo.gl/EaJ97e) (2016-05-02).

Boling, E., & Smith, K.M. (2014). Critical Issues in Studio Pedagogy: Beyond the Mystique and Down to Business. In B. Hokanson, & A. Gibbons (Eds.), Design in Educational Technology (pp. 37-56). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00927-8_3

Botha A., & Herselman M. (2015). A Teacher Tablet Toolkit to Meet the Challenges Posed by 21st Century Rural Teaching and Learning Environments. South African Journal of Education, 35(4). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n4a1218

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage. (https://goo.gl/JG4ZTQ) (2016-05-02).

Butcher, J. (2016). Can Tablet Computers Enhance Learning in Further Education? Journal of Further and Higher Education, 40(2), 207-226. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.938267

Chai, C.S., Koh, J.H.L., & Tsai, C.C. (2013). A Review of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(2), 31-51. (http://goo.gl/jjdJIy) (2016-05-02).

Chiong, C., & Shuler, C. (2010). Learning: Is there an App for that? Investigations of Young Children’s Usage and Learning with Mobile Devices and Apps. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop (http://goo.gl/MsnjV4) (2016-05-02).

Ciampa K. (2014). Learning in a Mobile Age: An Investigation of Student Motivation. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(1), 82-96. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12036

Crescenzi, L., & Grané, M. (2016). Análisis del diseño interactivo de las mejores apps educativas para niños de cero a ocho años [An Analysis of the Interaction Design of the Best Educational Apps for Children Aged Zero to Eight]. Comunicar, 46, 77-85. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C46-2016-08

Cresswell, J.W. & Miller, D.L. (2000). Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124-130. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Davies, R.S., Dean, D.I., & Ball, N. (2013). Flipping the Classroom and Instructional Technology Integration in a College-level Information Systems Spreadsheet Course. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(4), 563-580, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11423-013-9305-6

Dhir, A., Gahwaji, N.M., & Nyman, G. (2013). The Role of the iPad in the Hands of the Learner. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 19, 706-727. doi: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3217/jucs-019-05-0706

Falloon, G. (2013). Young Students Using iPads: App Design and Content Influences on their Learning Pathways, Computers & Education, 68, 505-521. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.06.006

Falloon, G. (2015). What's the Difference? Learning Collaboratively Using iPads in Conventional Classrooms, Computers & Education, 84, 62-77. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.01.010

Flewitt, R., Messer, D., & Kucirkova, N. (2015). New Directions for Early Literacy in a Digital Age: The iPad. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(3), 289-310. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468798414533560

Freire M.M. (2015). The Tablet is on the Table! The Need for a Teachers’ Self-hetero-eco Technological Formation Program. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 32(4), 209-220. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-10-2014-0022

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2009). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick: Aldine Pub. Co.

Gros, B. (2015). The Dialogue between Emerging Pedagogies and Emerging Technologies. In B. Gros & M. Maina (Eds.), The Future of Ubiquitous Learning. Learning Designs for Emerging Pedagogies (pp. 3-23) doi: http:// 10.1007/978-3-662-47724-3_1

Harris, K.D. (2013). Play, Collaborate, Break, Build, Share: Screwing around in Digital Pedagogy, Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Journal, 3(3). (https://goo.gl/btNntM) (2016-05-02).

Haßler B., Major L., & Hennessy S. (2015). Tablet Use in Schools: A Critical Review of the Evidence for Learning Outcomes. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 32(2), 138-156. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12123

Hennessy, S., & London, L. (2013). Learning from International Experiences with Interactive Whiteboards: The Role of Professional Development in Integrating the Technology. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k49chbsnmls-en

Johnson, L., Adams-Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2014). NMC Horizon Report: 2014 K-12 Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium. (http://goo.gl/04lpc2) (2016-05-02).

Kanematsu, H., & Barry, D.M. (2016). From Desktop Computer to Laptop and Tablets. In H. Kanematsu, & D. M. Barry (Eds.), STEM and ICT Education in Intelligent Environments (pp. 45-49). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19234-5_8

Kim H.J., & Jang H.Y. (2015). Factors Influencing Students' Beliefs about the Future in the Context of Tablet-based Interactive Classrooms. Computers and Education, 89, 1-15. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.08.014

Kim, K.J., & Frick, T.W. (2011). Changes in Student Motivation during Online Learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 44(1), 1-23. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/EC.44.1.a

Krippendorff, K. (1990). Metodología de análisis de contenido: Teoría y práctica. Barcelona: Paidós.

Krueger, R., & Casey, M. (2014). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research (Fifth Edition). London: Sage. (https://goo.gl/U5g4yb) (2016-05-02).

Kucirkova, N. (2014). iPads in Early Education: Separating Assumptions and Evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00715

Leung L., & Zhang R. (2016). Predicting Tablet Use: A Study of Gratifications-sought, Leisure Boredom, and Multitasking. Telematics and Informatics, 33(2), 331-341. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.08.013

Maich K., & Hall C. (2016). Implementing iPads in the Inclusive Classroom Setting. Intervention in School and Clinic, 51(3), 145-150. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1053451215585793

Marés, L. (2012). Tablets en educación, oportunidades y desafíos en políticas uno a uno. Buenos Aires: EOI: (http://goo.gl/w0cHpc) (2016-05-02).

Mascheroni, G., & Kjartan, O. (2014). Net Children Go Mobile. Risks and Opportunities. Milano: Educatt (http://goo.gl/a7CB5H) (2016-05-02).

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), Art. 20. (http://goo.gl/5tRTeY) (2016-05-02).

Nguyen, L., Barton, S.M., & Nguyen, L.T. (2015). iPads in Higher Education – Hype and Hope. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(1), 190-203. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12137

Price S., Jewitt C., & Crescenzi L. (2015). The Role of iPads in Pre-school Children's Mark Making Development. Computers and Education, 87, 131-141. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.003

Puchta, C. & Potter, J. (2004). Focus Group Practice. London: Sage Publications.

Ruiz, F.J. & Belmonte, A.M. (2014). Young People as Users of Branded Applications on Mobile Devices [Young People as Users of Branded Applications on Mobile Devices], Comunicar, 43, 73-81, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-07

Strauss, A. (1987). Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Suárez-Guerrero, C. (2014). Pedagogía Red. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 449, 76-80. (http://goo.gl/Ni0vlI) (2016-05-02).

Suárez-Guerrero, C., Lloret-Catalá, C., & Mengual-Andrés, S. (2015). Guía Práctica de la Educación Digital. Madrid: Samsung. (http://goo.gl/MA9TZ3) (2016-05-02).

Traxler, J., & Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2016). Conclusion: Contextual Challenges for the Next Generation. Mobile Learning: The Next Generation (pp. 208-226). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203076095

Traxler, J., & Wishart, J. (2011). Making Mobile Learning Work: Case Studies of Practice. Bristol: ESCalate, HEA Subject Centre for Education, University of Bristol. (http://escalate.ac.uk/8250) (2016-05-02).

Wibeck, V., Dahlgren, M.A., & Oberg, G. (2007). Learning in Focus Groups: an Analytical Dimension for Enhancing Focus Group Research. Qualitative Research, 7(2), 249-267. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468794107076023

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El presente estudio examina la trasformación de la dinámica del aula a través del uso educativo de las tabletas. La base empírica de este estudio se enmarca en el proyecto «Samsung Smart School», desarrollado entre Samsung y el Ministerio de Educación de España en el curso 2014-15. Se dotó de tabletas a profesores y alumnos de aulas de 5º y 6º de primaria de 15 centros de Educación Primaria de distintas comunidades autónomas del territorio Español. En suma el estudio se llevó a cabo con una muestra comprendida por 166 docentes. Se empleó una estrategia analítica cualitativa mediante: a) observación no participante, b) grupos focales, c) entrevistas semiestructuradas al profesorado y d) análisis de contenido de unidades didácticas. Dichas técnicas permitieron abordar el estudio de seis dimensiones pedagógicas (finalidad educativa, enfoque pedagógico, organización de contenidos y actividades, recursos didácticos, espacio y tiempo y evaluación del aprendizaje). Los hallazgos evidencian la tendencia del profesorado a trabajar con tabletas de forma transversal distintas competencias, centrarse en las actividades más que el contenido a través de las apps, asumir el reto de recuperar el juego como parte del aprendizaje y poner en práctica el aprendizaje basado en proyectos. En suma, la principal evidencia es que los docentes entienden la tableta no solo como un reto tecnológico, sino como la oportunidad para repensar sus modelos pedagógicos tradicionales.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

El uso de los dispositivos móviles en el aula resulta un tema de especial actualidad e interés para la comunidad educativa (Johnson, Adams-Becker, Estrada, & Freeman, 2014); no solo por las múltiples posibilidades que tiene para enriquecer el proceso educativo (Traxler & Wishart, 2011) sino también por la aceptación, accesibilidad y expectativas educativas que generan (Maich & Hall, 2016). Esta aceptación no responde únicamente a la cada vez más sofistica evolución de los dispositivos tecnológicos en la educación (Kanematsu & Barry, 2016), sino también a otros factores como: el incremento de ventas de los dispositivos móviles sobre los ordenadores personales, el desarrollo exponencial de aplicaciones educativas, las posibilidades de acceso a recursos educativos o la experiencia de ubicuidad constante para abrir nuevas rutas de enseñanza y aprendizaje (Haßler, Major, & Hennessy, 2015; Kim & Frick, 2011).

El incremento masivo de dispositivos personales en los hogares y las escuelas plantea importantes cuestiones sobre su uso y rol en el desarrollo y proceso de aprendizaje (Chiong & Shuler, 2010, Crescenzi & Grané, 2016; Price, Jewitt, & Crescenzi, 2015; Ruíz & Belmonte, 2014). La presencia de estos dispositivos en la vida de los estudiantes permite hablar con fundamento sobre alternativas educativas emergentes con tecnología como BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) (Arias-Ortiz & Cristia, 2014) o «flipped classroom» (Davies, Dean, & Ball, 2013). Este potencial se agranda cuando existe tanto o más tecnología en los hogares que en las escuelas (Mascheroni & Kjartan, 2014).

Sin embargo, aun reconociendo una serie de bondades sobre el uso de los dispositivos móviles en el aula, no es posible afirmar con rotundidad que exista un «impacto positivo» de su incorporación a la educación formal. Existen tantos estudios que indican que su uso mejora la calidad educativa frente al aprendizaje tradicional como estudios que no encuentran suficiente base empírica para hablar de mejores resultados. Al respecto Nguyen, Barton y Nguyen (2015) ponen en evidencia que, aunque el uso de las tabletas en el contexto educativo mejora la experiencia de aprendizaje, no necesariamente se producen mejoras en términos de rendimiento. Dichos estudios coinciden con los trabajos de Leung y Zhang (2016) así como Dhir, Gahwaji y Nyman (2013), cuyos resultados indican que mientras el uso de tabletas puede beneficiar la motivación hacia el aprendizaje, su impacto real resulta limitado. En todo caso las mejoras en la motivación hacia el aprendizaje se ponen de manifiesto a través del desafío, la curiosidad, el control, la cooperación y la competitividad que el uso de estos dispositivos propician en el aula (Ciampa, 2014).

Por ello los estudios sobre el uso educativo de las tabletas indican aquello que funciona y aquello que no, los escenarios o condiciones que deben darse para que la tecnología y el «mobile learning» funcionen en clase. Es decir, los estudios proporcionan modelos de buenas prácticas que buscan servir de guía a los profesores. De aquí que las preguntas que impulsen los estudios educativos sobre el uso de las tabletas a día de hoy no deben de girar alrededor de si estos dispositivos son o no efectivos, sino sobre cómo se emplean o si sus prácticas siguen condicionadas sobre la base de modelos pedagógicos tradicionales o los modelos basados en el libro de texto (Marés, 2012).

Las tabletas pueden contribuir de distintas maneras a mejorar la experiencia de aprendizaje en el aula, no solo el rendimiento académico. Por ejemplo, Kucirkova (2014) indica que el valor educativo de las tabletas radica en las características de sus apps y en cómo su contenido puede influir en la participación en el aula. De forma similar, Falloon (2013) demostró que el diseño y contenido de las aplicaciones son condición indispensable para aprender en un entorno motivante y productivo, evidenciando en su trabajo la efectividad de un programa de intervención basado en la selección minuciosa de apps para el aula. En otro trabajo, el mismo Falloon (2015) pone de manifiesto que el uso de las tabletas en el aula puede ampliar el aprendizaje de forma regular siempre que se realice a través de un diseño deliberado de itinerarios basados en la colaboración, el debate, la negociación y cambiando roles en el trabajo de equipo. Este tipo de estudios, al igual que el que aquí se presenta, hacen hincapié en el componente pedagógico más que en el tecnológico (Flewitt, Messer, & Kucirkova, 2015).

En dicho sentido, según Ciampa (2014) la investigación académica sobre el uso de las tabletas en el aula debe orientarse hacia los beneficios pedagógicos, sus posibilidades en el aprendizaje autodirigido, la personalización de los dispositivos, el trabajo en equipo, el aumento y mejora de la comunicación y la colaboración, el incremento del aprendizaje autónomo, el compromiso y la motivación de los alumnos, las posibilidades del aprendizaje individualizado (personalizado) la atención más eficaz a las necesidades educativas especiales, así como, según Kim y Jang (2015) la creación de entornos de aula interactiva. Todo esto supone parte de la «cultura pedagógica» en torno a la tecnología, y a las tabletas, que todo docente debe desarrollar (Freire, 2015).

Por tanto, el uso de la tecnología en general, y el uso de tabletas en particular, deben girar bajo la premisa de que la pedagogía implica a la tecnología, no al revés (Hennessy & London, 2013). Sin un modelo pedagógico alternativo basado en buenas prácticas, los dispositivos móviles pueden ser tan solo un recurso sofisticado en el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje, parte del mobiliario educativo (Suárez-Guerrero, 2014). De aquí que el objetivo de la presente investigación se centre en comprender y caracterizar el modelo pedagógico con el que se promueve el uso educativo de las tabletas en el aula, más que determinar si hay una relación causal entre uso de tabletas y mejora en el rendimiento académico. Esta línea, coincide con el trabajo de Botha y Herselman (2015) a la hora de entender el proceso de integración de las tabletas como parte de un ecosistema basado en la tecnología y la pedagogía.

Para conocer la percepción pedagógica sobre la transformación digital del aula a través del uso educativo de las tabletas se ha analizado el proyecto «Samsung Smart School», promovido por Samsung España en convenio con el Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte de España y las Comunidades Autónomas implicadas en dicho proyecto. La investigación analiza los cambios educativos que se han generado en la dinámica del aula producto de la aplicación del proyecto «Samsung Smart School» en España durante el curso 2014-15. Este proyecto impulsó el uso de las tabletas en aulas de 5º y 6º en 15 centros de Educación Primaria de las comunidades autónomas de Aragón, Asturias, Canarias, Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Extremadura, Galicia, Islas Baleares, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia, Navarra, así como de Ceuta y Melilla.

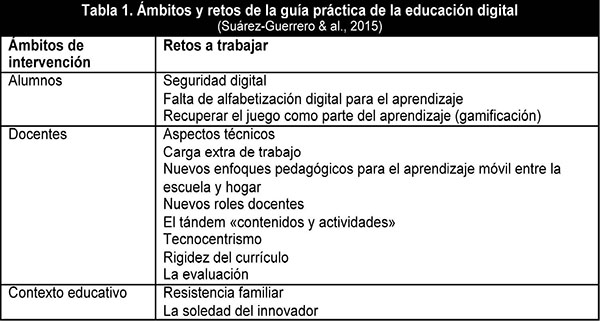

Dado que comprender el proceso de apropiación docente de la tecnología es fundamental para identificar retos y facilitar este proceso a otros docentes, este estudio condujo a la elaboración de la «Guía Práctica de la Educación Digital». Esta guía aportó trece recomendaciones didácticas estructuradas en tres grandes ámbitos de intervención (Tabla 1) para que los docentes en general y, los docentes del proyecto «Samsung Smart School» en particular, puedan mejorar su práctica educativa con las tabletas (Suárez-Guerrero, Lloret-Catalá, & Mengual-Andrés, 2015). En este artículo se detalla el proceso de investigación y los resultados que sostienen la guía práctica.

2. Material y métodos

2.1. Objeto de estudio

El presente estudio pretendió conocer, desde la actividad y visión del docente, los cambios pedagógicos en el aula generados por el uso de la tableta dentro del marco del proyecto «Samsung Smart School» en España durante el curso 2014-15. Para la implementación del proyecto el Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte de España, a través del Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y de Formación del Profesorado (INTEF), las administraciones educativas en las Comunidades Autónomas y Samsung seleccionaron los centros de educación primaria participantes; uno por comunidad autónoma más Ceuta y Melilla, según los siguientes criterios: a) colegios de zonas rurales alejadas, b) áreas con un alto abandono escolar, c) zonas con una ratio elevada de desempleo y d) centros con alumnos de Educación Especial.

2.2 Diseño

La presente investigación se llevó a cabo a través de una aproximación cualitativa mediante la Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2009) y tuvo por objeto de estudio el uso educativo de tabletas en aulas de primaria desde seis dimensiones pedagógicas:

• Finalidad educativa: Conocer las competencias que se proponen desarrollar en el aula con el uso de tabletas.

• Enfoque didáctico: Conocer bajo qué enfoque de aprendizaje el docente usa las tabletas en el aula.

• Contenidos y actividades: Conocer qué y cómo se desarrollan los contenidos de aprendizaje con el uso de las tabletas.

• Recursos didácticos: Conocer qué materiales emplea el docente para el desarrollo del aprendizaje a través de las tabletas.

• Espacio y tiempo: Conocer cómo las tabletas transforman el entorno educativo del aula y cómo se gestiona el tiempo.

• Evaluación del aprendizaje: Conocer cómo se emplea las tabletas para evaluar el aprendizaje de los alumnos.

El estudio de las dimensiones anteriores se abordó a través de cuatro técnicas cualitativas de recogida de información: a) observación no participante, b) grupos focales, c) entrevistas virtuales y d) análisis de contenido de las unidades didácticas del proyecto.

2.3. Participantes y procedimiento

La población del presente estudio estuvo compuesta por 15 centros de educación primaria con un total de 166 docentes y 766 alumnos. El 29,8% de los docentes eran hombres y el 67,5% fueron mujeres. La edad media del profesorado fue de 40,5 años. Por lo que respecta al alumnado, un 44,5% eran chicas y un 55,5% chicos, con edades comprendidas entre los 10 y 11 años.

En primer lugar se realizó una observación no participante en cuatro de las unidades de educación primaria que participaban en el proyecto, ubicadas en las provincias de Zaragoza, Guadalajara, Madrid y Murcia. La elección de dichas unidades se llevó a cabo mediante un muestreo aleatorio simple. En el desarrollo de la técnica participaron tres observadores que asumieron el rol de observador. A través de una lista de cotejo se subrayaron las conductas de los docentes y de los alumnos relacionadas con las dimensiones de análisis propuestas. En total se registraron un total de doce listas de cotejo para su posterior tratamiento y análisis.

En segundo lugar se empleó la técnica del grupo focal. Para lograr en términos generales la representación de todos los centros se configuraron dos grupos focales de dos horas de duración con profesores (n=7) y embajadores –profesores coordinadores del proyecto– de los centros (n=8) participantes en el proyecto. Los participantes se seleccionaron mediante un procedimiento de muestreo por conglomerados. La estructura de la dinámica versó sobre: a) hábitos, relación y efecto del uso de las tabletas en la actitud de los alumnos; b) DAFO sobre el trabajo en el aula con tecnología, y c) evaluación de la experiencia con el proyecto «Samsung Smart School»: percepción, potencial, adecuación a perfiles/centros, optimizaciones, recomendaciones para su implementación. En esencia, la ventaja de los grupos focales de tamaño reducido radica en que cada participante puede tener voz (Wibeck, Dahlgren, & Oberg, 2007), además resulta una técnica común para recoger información cualitativa en la investigación educativa (Puchta & Potter, 2004). Ambas sesiones se desarrollaron en paralelo en dos salas de observación con cristal unidireccional, siendo dirigidas y dinamizadas por dos expertos investigadores que previamente recibieron formación con el objeto de no desviarse de las dimensiones del estudio. Los investigadores del proyecto mantuvieron contacto con los dinamizadores de la sesión y la registraron para su posterior tratamiento y análisis.

Con el objeto de complementar la información obtenida en los grupos focales se decidió realizar entrevistas semiestructuradas. La muestra recogió un total de trece entrevistas virtuales, abarcando al menos un profesor/embajador de cada uno de los centros participantes en el proyecto. Mediante un guion semiestructurado de 10 preguntas abiertas basadas en las seis dimensiones del estudio, alrededor de 30 minutos –a través de Adobe Connect– se recogió la percepción del entrevistado sobre su experiencia en la integración de la tecnología en el aula, las dificultades que había encontrado y las soluciones y recomendaciones que veía posibles hacer a otros docentes con la intención de optimizar el proyecto «Samsung Smart School». Las trece entrevistas fueron grabadas en vídeo para su posterior análisis y tratamiento.

Por último se llevó a cabo un análisis cualitativo de contenido (Mayring, 2000) de 80 unidades didácticas empleadas por los centros participantes en el programa. Con este análisis se buscó entender la forma en que se planificaba el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje con las tabletas, así como detectar buenas prácticas en el diseño curricular con tecnología.

2.4. Recolección y análisis de datos

Los datos de este estudio fueron recogidos entre diciembre de 2014 y mayo de 2015. Las entrevistas fueron grabadas en vídeo para su posterior análisis, previa autorización de los entrevistados. La observación no participante y los grupos focales fueron registrados manualmente mientras que las unidades didácticas fueron procesadas en formato RTF. El contenido de las grabaciones, las observaciones, las entrevistas y las unidades didácticas se almacenaron, procesaron y analizaron respetando el anonimato de los participantes.

La transcripción de los datos registrados de los grupos focales, las entrevistas y la observación no participantes produjo una gran cantidad de información; por ello el enfoque de análisis sobre los objetivos del estudio ayudó en la gestión de la información (Krueger & Casey, 2014). Los datos recolectados a través de los instrumentos se volcaron y analizaron mediante el software Atlas.ti 7, permitiendo poder analizar el contenido de los videos sin necesidad de realizar una transcripción. Del mismo modo la posibilidad de trabajar con ficheros RFT y PDF ahorró tiempo de transcripción y análisis. El análisis de contenido supone una técnica de investigación adecuada para formular, desde cierta información, inferencias reproducibles y válidas que pueden ser entendidas en el contexto del estudio (Krippendorff, 1990). Por ello aquí se llevó a cabo un proceso de codificación mixto –deductivo e inductivo– partiendo de la base de las seis dimensiones del estudio y permitiendo una codificación emergente (Strauss, 1987). A través de un análisis cualitativo de tipo estimatorio –inferir relaciones en vez de generar hipótesis– (Krippendorff, 1990) se realizó un análisis individual temático de los datos, a través de su lectura, codificación, recodificación, asignación de familias y categorización de los datos –por dimensiones del estudio– (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Los temas generados fueron revisados por los autores de forma conjunta con el fin de llegar a un acuerdo común sobre los hallazgos. La validez del método empleado en la presente investigación queda, por tanto, enraizada en el cumplimiento de los criterios descritos por Creswell y Miller (2000): a) triangulación con datos e investigadores; b) comprobación con los miembros de la investigación.

3. Análisis y resultados

A continuación se presentan los resultados procedentes del análisis de la observación no participante, las entrevistas, los grupos focales y el análisis de contenido de las unidades didácticas organizadas en las seis dimensiones de estudio:

3.1. Finalidad educativa

En las unidades didácticas generadas en el marco del proyecto se puede comprobar, gracias al análisis de contenido y las observaciones, una tendencia clara a desarrollar actividades de aprendizaje con tabletas que integran las competencias clave en las distintas áreas curriculares. No obstante, en el análisis de las unidades didácticas se puede ver un marcado énfasis por desarrollar preferentemente la competencia en comunicación lingüística y la competencia digital. Por contra, las que menos se trabajan son la competencia matemática y las competencias básicas en ciencia y tecnología. Cabe destacar que, por las características del proyecto «Samsung Smart School», los docentes pudieron trabajar la competencia digital donde no era posible por limitaciones de acceso o economía familiar: «Si no fuese por el proyecto no habría estimulado el desarrollo de la competencia digital» (entrevista 7).

Con relación a la competencia digital, gracias a las entrevistas y a los grupos focales, los docentes del proyecto plantean el uso de tabletas a actividades de aprendizaje relacionadas con la búsqueda, selección, organización y uso de la información, ya sea individualmente o en equipos. También existe unanimidad en que el uso educativo de las tabletas conectadas a Internet genera una expectativa diferente en los alumnos sobre la fuente de información.

3.2. Enfoque didáctico

Según las entrevistas y los grupos focales, los docentes del proyecto destacan que el uso eficaz de la tableta en el aula no es posible sin un cambio metodológico. También señalan que este cambio debe encaminarse hacia la adopción, fundamentalmente, de metodologías activas como el aprendizaje basado en proyectos (ABP) y el aprendizaje colaborativo.

Otro aspecto singular que los docentes señalan es que, cuando no existe una pedagogía que explote las oportunidades educativas, la tableta puede convertirse en un sofisticado reproductor de tareas monótonas. Por ejemplo en el grupo focal de embajadores, un docente destacó que «si no tienes una pedagogía, las tabletas no funcionan». Ahora bien, esa pedagogía no consiste en mejorar la docencia como dictado de clase, sino en entender las nuevas actividades que los alumnos son capaces de hacer cuando aprenden con la tableta, ya sea de forma personal o en grupo. Esto significa que, aunque el ABP y el aprendizaje colaborativo sean rasgos distintivos en el proyecto, existen otros retos pedagógicos para explotar mejor el potencial de las tabletas en el aula.

3.3. Contenidos y actividades de aprendizaje

Respecto a las actividades, gracias a las entrevistas y los grupos focales, se puede destacar que los docentes tienen la impresión de que la tableta se ha convertido en el cuaderno del alumno que le permite gestionar digitalmente su aprendizaje. Este «nuevo cuaderno» introduce el desarrollo de actividades distintas a leer o escribir, además de promover otras, como las de investigación o las basadas en multimedia, principalmente. Es por ello que para muchos docentes la función principal de la tableta en el aula no es proporcionar contenidos, como es el caso del libro, sino más bien como se pudo ver en las observaciones, permitir que los alumnos realicen y se involucren en actividades más novedosas y en la gestión de su propio aprendizaje. Al respecto de esta idea, un docente destacó que «una clase normal, después de utilizar las tabletas, ya no seduce a los alumnos… Los docentes tenemos que reinventar actividades» (entrevista 11).

Según el análisis de contenido de las unidades didácticas, dos tercios de las unidades analizadas vertebran con claridad un uso colaborativo de las tabletas, la mayoría de las veces fomentando la investigación y el diálogo ante el trabajo individual y competitivo. Además, de las unidades didácticas analizadas, muy pocas limitan el uso de las tabletas al desarrollo de un único contenido curricular.

Gracias a las entrevistas y a los grupos focales se ha podido apreciar que el docente asume que ya no es la única fuente de información y que los alumnos son parte activa del trabajo en clase. También detectan que las tabletas abren posibilidades de creación asociadas a la actividad gráfica en el aula, editar bocetos, realizar presentaciones, maquetar un programa de radio, investigar en red, crear libros y editar vídeos o fotos. Todo esto puede realizarse no solo individualmente, sino también de forma cooperativa, gracias a este dispositivo.

3.4. Recursos didácticos

Se ha detectado una tendencia en el uso docente de apps no ligadas a un contenido específico, sino al uso de apps genéricas que permiten desarrollar distintos tipos de actividades de aprendizaje en cualquier área. Del abanico de aplicaciones empleadas por los docentes, las más utilizadas entrarían en la categoría de «tratamiento de imagen y el sonido», sobre todo aquellas orientadas al diseño y creación de contenido (cámara, Tellagami, Aurasma, editor de vídeo y audio, etc.) así como aplicaciones que permiten la comunicación y la búsqueda de información. La constante, vista en el análisis de las unidades didácticas, es que los docentes buscan usar estas aplicaciones para crear actividades. Por ejemplo, «las tabletas te ofrecen la posibilidad de crear actividades de aprendizaje y no solo realizar consultas como en el caso del libro» (entrevista 4).

Pero la tableta no es el único material en el aula. Tras el análisis de las unidades didácticas y de las visitas a los centros se aprecia un uso educativo de la tableta articulado a la pantalla de TV o a la Pizarra Digital Interactiva (cuando existe), así como al portátil/PC y, con una menor frecuencia, al teléfono móvil. No obstante, existen diferencias sobre su uso en aula. Por ejemplo, según las entrevistas docentes, las tabletas pueden añadir versatilidad a la dinámica de clase por encima de los portátiles. Por otro lado, las PDI son vistas como dispositivos tecnológicos que reproducen los modelos pedagógicos tradicionales, mientras que las tabletas reforzarían claramente el trabajo en grupo.

Un buen complemento del trabajo en aula, asociado normalmente al uso de la aplicación S Note, ha sido el lápiz digital, S Pen. Se ha observado, tras el análisis de las unidades didácticas, que con el S Pen se realizan numerosas actividades que van desde la escritura a mano, para tomar notas, al dibujo, siendo así este dispositivo un valor añadido en el ámbito educativo.

Otro aspecto muy importante, destacado en las observaciones y los grupos focales, es que para los docentes la tableta puede ser una herramienta para personalizar el aprendizaje. Frente al uso de la pizarra convencional y la pizarra digital, que los docentes asocian a la difusión de un contenido para la clase, la tableta ha significado un avance respecto a la atención individualizada y al seguimiento del trabajo de los alumnos. No obstante, también indican que para lograrlo de forma eficiente, se requiere prever más horas de planificación y desarrollo de las actividades con la tableta.

Otro aspecto positivo detectado por los docentes es la sostenibilidad, ya que gracias a las tabletas ya no se necesita fotocopiar material, pero también existe la nueva preocupación docente por resolver los problemas de compatibilidad tecnológica entre los archivos, sistemas operativos y aplicaciones web.

3.5. Entorno y tiempo

Los docentes del proyecto detectan, según las observaciones, las entrevistas y los grupos focales, que los alumnos son conscientes de los cambios que han tenido lugar en el aula, no solo por la presencia física de la tecnología, sino también por el giro experimentado en las actividades de aprendizaje, el cambio del rol docente y del rol del alumno, así como por una nueva forma de organización física del aula. Por ejemplo en el grupo focal de docentes, uno de ellos destacó que «los alumnos ya no están en hileras viendo espaldas. Las clases ahora son móviles». Algunos de estos cambios consisten en asumir que, físicamente, las aulas han pasado de ser entornos rígidos con alumnos sentados en filas escuchando al docente a ser, gracias a la movilidad que brindan las tabletas, espacios abiertos y flexibles que sostienen otra dinámica en la que todos pueden hablar con todos.

Otro aspecto destacable sobre el entorno educativo con tabletas, extraído del análisis de las unidades didácticas, es que pocas veces se usa para salir de ella y transformar educativamente otros espacios.

Respecto al tiempo que necesitan los alumnos para trabajar de forma autónoma con la tableta, los docentes del proyecto han dado respuestas heterogéneas. No se ha llegado a detectar un tiempo promedio, ya que las respuestas han variado en función de las experiencias previas de los alumnos con la tecnología, así como de la frecuencia de uso de las tabletas en aula. Lo que sí se destaca con nitidez es que se requiere de un tiempo, tanto para que el alumno domine de forma autónoma la tableta, como para experimentar un proceso de transición que le permita evolucionar desde el uso de la tableta como un juguete al uso de la misma como herramienta de aprendizaje.

3.6. Evaluación del aprendizaje

Aunque exista un grupo de docentes que señalan, en las visitas, las entrevistas y en los grupos focales, que la evaluación es «nuestra pequeña gran asignatura pendiente», la mayoría de ellos han detectado por lo menos cuatro cambios en la forma de evaluar: evaluación como juego, la introducción de rúbricas, la inmediatez del feed-back y el uso de la evaluación tipo test en red. En todas estas opciones, herramientas como Socrative, Kahoot, Rubistar o los formularios de Google son las más destacadas. Ahora bien, gracias al análisis de las unidades didácticas, se detecta también la convivencia de formas tradicionales de evaluación con otras alternativas, como co-evaluación, autoevaluación e incluso con la posibilidad de personalización del aprendizaje. Como se destacó en el grupo focal de docentes: «A ti te da más juego, puedes hacer un material más específico para ese alumno en concreto».

4. Discusión y conclusiones

El presente estudio forma parte de una línea emergente de investigación educativa denominada pedagogía digital. Toda esta pedagogía está en construcción y se centra, fundamentalmente, en evaluar los modelos educativos que emplean la tecnología en el aula, así como detectar posibles usos, retos y tendencias en otros espacios educativos (Boling & Smith, 2014; Chai, Koh, & Tsai, 2013, Gros, 2015; Harris, 2013). El centro de atención de esta línea, como en esta investigación, no es la tecnología en sí misma, sino conocer qué se puede hacer educativamente con ella (Flewitt, Messer, & Kucirkova, 2015).

No obstante, hay que señalar que este estudio se realizó en condiciones tecnológicas óptimas ya que, gracias al proyecto «Samsung Smart School», tanto profesores como alumnos dispusieron de una tableta por persona, así como acceso a Internet. Por ello es preciso destacar que los hallazgos pedagógicos en este trabajo deben ser interpretados cuando el acceso a la tecnología no es un problema.

El análisis de contenido sobre los datos generados por las cuatro técnicas cualitativas permite inferir (Braun & Clarke, 2013) que los docentes del proyecto encaran el desafío de la tableta no solo como un reto tecnológico, sino que construyen una visión pedagógica de su uso educativo (Butcher, 2016). La configuración de esta visión pedagógica sobre la tableta, manifestada al categorizar las seis dimensiones estudiadas, está presente en la actividad, percepción y programación docente con las tabletas.

Por ello, y contrariamente a lo que pueda pensarse, la visión pedagógica de los docentes del proyecto sobre la tableta no está presente solo cuando dan respuesta a la pregunta «¿con qué aprender?», asociada a las apps en este estudio, sino que también está presente en la definición de la finalidad educativa, en la concepción de una didáctica, en el desarrollo de actividades, en la representación del espacio y tiempo educativo y en la evaluación del aprendizaje. La tecnología abre, como se puede ver en los resultados, un abanico amplio de nuevas funciones educativas que el profesor asume como parte de su actividad curricular. Esta parece ser la tendencia al hablar del valor educativo de las nuevas condiciones que añaden los dispositivos móviles al aprendizaje (Traxler & Kukulska-Hulme, 2016).

Entre las principales funciones educativas que añade la tableta conectada a Internet en la dinámica del aula en primaria, los docentes del proyecto reconocen que aunque se trabaje más la competencia en comunicación lingüística y la competencia digital es posible trabajar de forma transversal distintas competencias, que el uso educativo de la tableta implica un cambio en la metodología docente que de paso al desarrollo del aprendizaje basado en proyectos (ABP) y el aprendizaje colaborativo, que si bien es cierto que las tabletas permiten el acceso a la información su principal uso didáctico no es dotar de contenido específico sino, gracias a las apps genéricas, desarrollar distintos tipos de actividades, que el paso de consumir a producir información supone el desarrollo de la competencia digital asociada especialmente al lenguaje multimedia, que gracias al uso de la tabletas se puede abrir un filón de cara a la personalización del aprendizaje y la co-evaluación (Botha & Herselman, 2015).

Como se ha destacado en las entrevistas y en los grupos focales, hace falta entender que las tabletas auspician –que no significa, causan– una serie de transiciones como: la evolución de la tableta como juguete a tableta como herramienta de aprendizaje, de las pedagogías de consumo de la información a pedagogías de creación, de las pedagogías estáticas a las pedagogía móviles, del potencial del libro texto al potencial del cuaderno digital, de los contenidos a las actividades, de la gestión de logros a la gestión de errores o, la principal, de la imagen de tecnología como herramienta neutral a una que favorece cambios en la cultura estándar del aula.

El cambio educativo no es únicamente la tableta en aula, sino la herramienta simbólica con la que los docentes piensan todos los elementos pedagógicos desde, como se ha podido comprobar, nuevas funciones y transiciones que exigen ir más allá de la réplica de lo antiguo con algo nuevo.

Apoyos y reconocimientos

El presente estudio se ha realizado gracias a Samsung Electronics Iberia y ha contado con la colaboración del Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte del Gobierno de España y las distintas Comunidades Autónomas participantes en el proyecto.

Referencias

Arias-Ortiz, E., & Cristia, J. (2014). El BID y la tecnología para mejorar el aprendizaje: ¿Cómo promover programas efectivos? IDB Technical Note (Social Sector. Education Division), IDB-TN-670. (http://goo.gl/EaJ97e) (2016-05-02).

Boling, E., & Smith, K.M. (2014). Critical Issues in Studio Pedagogy: Beyond the Mystique and Down to Business. In B. Hokanson, & A. Gibbons (Eds.), Design in Educational Technology (pp. 37-56). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00927-8_3

Botha A., & Herselman M. (2015). A Teacher Tablet Toolkit to Meet the Challenges Posed by 21st Century Rural Teaching and Learning Environments. South African Journal of Education, 35(4). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n4a1218

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage. (https://goo.gl/JG4ZTQ) (2016-05-02).

Butcher, J. (2016). Can Tablet Computers Enhance Learning in Further Education? Journal of Further and Higher Education, 40(2), 207-226. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.938267

Chai, C.S., Koh, J.H.L., & Tsai, C.C. (2013). A Review of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(2), 31-51. (http://goo.gl/jjdJIy) (2016-05-02).

Chiong, C., & Shuler, C. (2010). Learning: Is there an App for that? Investigations of Young Children’s Usage and Learning with Mobile Devices and Apps. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop (http://goo.gl/MsnjV4) (2016-05-02).

Ciampa K. (2014). Learning in a Mobile Age: An Investigation of Student Motivation. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(1), 82-96. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12036

Crescenzi, L., & Grané, M. (2016). Análisis del diseño interactivo de las mejores apps educativas para niños de cero a ocho años [An Analysis of the Interaction Design of the Best Educational Apps for Children Aged Zero to Eight]. Comunicar, 46, 77-85. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C46-2016-08

Cresswell, J.W. & Miller, D.L. (2000). Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124-130. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Davies, R.S., Dean, D.I., & Ball, N. (2013). Flipping the Classroom and Instructional Technology Integration in a College-level Information Systems Spreadsheet Course. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(4), 563-580, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11423-013-9305-6

Dhir, A., Gahwaji, N.M., & Nyman, G. (2013). The Role of the iPad in the Hands of the Learner. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 19, 706-727. doi: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3217/jucs-019-05-0706

Falloon, G. (2013). Young Students Using iPads: App Design and Content Influences on their Learning Pathways, Computers & Education, 68, 505-521. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.06.006

Falloon, G. (2015). What's the Difference? Learning Collaboratively Using iPads in Conventional Classrooms, Computers & Education, 84, 62-77. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.01.010

Flewitt, R., Messer, D., & Kucirkova, N. (2015). New Directions for Early Literacy in a Digital Age: The iPad. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(3), 289-310. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468798414533560

Freire M.M. (2015). The Tablet is on the Table! The Need for a Teachers’ Self-hetero-eco Technological Formation Program. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 32(4), 209-220. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-10-2014-0022

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2009). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick: Aldine Pub. Co.

Gros, B. (2015). The Dialogue between Emerging Pedagogies and Emerging Technologies. In B. Gros & M. Maina (Eds.), The Future of Ubiquitous Learning. Learning Designs for Emerging Pedagogies (pp. 3-23) doi: http:// 10.1007/978-3-662-47724-3_1

Harris, K.D. (2013). Play, Collaborate, Break, Build, Share: Screwing around in Digital Pedagogy, Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Journal, 3(3). (https://goo.gl/btNntM) (2016-05-02).

Haßler B., Major L., & Hennessy S. (2015). Tablet Use in Schools: A Critical Review of the Evidence for Learning Outcomes. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 32(2), 138-156. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12123

Hennessy, S., & London, L. (2013). Learning from International Experiences with Interactive Whiteboards: The Role of Professional Development in Integrating the Technology. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k49chbsnmls-en

Johnson, L., Adams-Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2014). NMC Horizon Report: 2014 K-12 Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium. (http://goo.gl/04lpc2) (2016-05-02).

Kanematsu, H., & Barry, D.M. (2016). From Desktop Computer to Laptop and Tablets. In H. Kanematsu, & D. M. Barry (Eds.), STEM and ICT Education in Intelligent Environments (pp. 45-49). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19234-5_8

Kim H.J., & Jang H.Y. (2015). Factors Influencing Students' Beliefs about the Future in the Context of Tablet-based Interactive Classrooms. Computers and Education, 89, 1-15. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.08.014

Kim, K.J., & Frick, T.W. (2011). Changes in Student Motivation during Online Learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 44(1), 1-23. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/EC.44.1.a

Krippendorff, K. (1990). Metodología de análisis de contenido: Teoría y práctica. Barcelona: Paidós.

Krueger, R., & Casey, M. (2014). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research (Fifth Edition). London: Sage. (https://goo.gl/U5g4yb) (2016-05-02).

Kucirkova, N. (2014). iPads in Early Education: Separating Assumptions and Evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00715

Leung L., & Zhang R. (2016). Predicting Tablet Use: A Study of Gratifications-sought, Leisure Boredom, and Multitasking. Telematics and Informatics, 33(2), 331-341. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.08.013

Maich K., & Hall C. (2016). Implementing iPads in the Inclusive Classroom Setting. Intervention in School and Clinic, 51(3), 145-150. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1053451215585793

Marés, L. (2012). Tablets en educación, oportunidades y desafíos en políticas uno a uno. Buenos Aires: EOI: (http://goo.gl/w0cHpc) (2016-05-02).

Mascheroni, G., & Kjartan, O. (2014). Net Children Go Mobile. Risks and Opportunities. Milano: Educatt (http://goo.gl/a7CB5H) (2016-05-02).

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), Art. 20. (http://goo.gl/5tRTeY) (2016-05-02).

Nguyen, L., Barton, S.M., & Nguyen, L.T. (2015). iPads in Higher Education – Hype and Hope. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(1), 190-203. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12137

Price S., Jewitt C., & Crescenzi L. (2015). The Role of iPads in Pre-school Children's Mark Making Development. Computers and Education, 87, 131-141. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.003

Puchta, C. & Potter, J. (2004). Focus Group Practice. London: Sage Publications.

Ruiz, F.J. & Belmonte, A.M. (2014). Young People as Users of Branded Applications on Mobile Devices [Young People as Users of Branded Applications on Mobile Devices], Comunicar, 43, 73-81, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-07

Strauss, A. (1987). Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Suárez-Guerrero, C. (2014). Pedagogía Red. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 449, 76-80. (http://goo.gl/Ni0vlI) (2016-05-02).

Suárez-Guerrero, C., Lloret-Catalá, C., & Mengual-Andrés, S. (2015). Guía Práctica de la Educación Digital. Madrid: Samsung. (http://goo.gl/MA9TZ3) (2016-05-02).

Traxler, J., & Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2016). Conclusion: Contextual Challenges for the Next Generation. Mobile Learning: The Next Generation (pp. 208-226). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203076095

Traxler, J., & Wishart, J. (2011). Making Mobile Learning Work: Case Studies of Practice. Bristol: ESCalate, HEA Subject Centre for Education, University of Bristol. (http://escalate.ac.uk/8250) (2016-05-02).

Wibeck, V., Dahlgren, M.A., & Oberg, G. (2007). Learning in Focus Groups: an Analytical Dimension for Enhancing Focus Group Research. Qualitative Research, 7(2), 249-267. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468794107076023

Document information

Published on 30/09/16

Accepted on 30/09/16

Submitted on 30/09/16

Volume 24, Issue 2, 2016

DOI: 10.3916/C49-2016-08

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?