Abstract

195 countries, 7,000+ officially known languages, thousands of hidden dialects. When we think of languages, words that come to mind are often related to communication. Especially with knowing multiple languages, we think of amplifying relations with interpersonal communication. Yet, a problem exists with the lack of knowledge about bilingualism’s advantage besides these perceptions in globalized societies. This issue impacts monolinguals because of decreasing language education neglecting bilingualism’s increase of cognitive skills. Limited research on the benefits of bilingualism among adolescents exacerbates this problem, as existing studies often focus on infants and older adults, considering these age groups depict clear benefits without confounding variables. However, adolescents have the greatest adaptability for language acquisition, asserting suitability in measuring bilingualism before brain development hinders learning abilities in adulthood (Smith, 2018). The purpose of this study is to underscore the beneficial advantage bilingualism—specifically among adolescents—provides unconsciously daily, ultimately aiding to promote language education.

Introduction

One of the foremost advantages that comes with having a history of both large, unifying empires, and small, fragmented kingdoms is the rich diversity that presents itself as the daily multilingual experience in India. Comprising around 200 languages and dialects, Indian culture is prominent in its heterogeneity, which is why spending an entire childhood in such a country compelled me to inquire about a seemingly simple part of life that has a surprisingly greater impact, especially when compared to largely monolingual countries, like the United States. Many cultural factors, such as societal attitudes toward multilingualism and the role of language in identity formation in countries like India, play a crucial role in shaping the cognitive effects of bilingualism.

Review of Literature

I. History

Since the early 17th century frontier settlements, bilingualism, known as fluency in two languages, has been a part of the journey towards the growth and development of the United States. Considered to be an American tradition, bilingual education began with the settlement of Polish immigrants in colonial Virginia that eventually brought about the establishment of the first dual language schools through increasing ethnic influence (Goldenberg & Wagner, 2015). Ultimately, after depreciating in the 1920s era, bilingualism was reintroduced to American schooling systems through the Bilingual Education Act in 1968 (Goldenberg & Wagner, 2015). However, this rise in dual languages was accompanied by a perceived negative connotation of the effects of bilingualism on cognition. Many of the early scientific studies focusing on this relationship concluded that bilingualism negatively impacted children by delaying their language development due to non-selective coactivation: the unconscious word use and pronunciation from a second language when presently talking in the first. In addition, the studies even depicted a delay in language acquisition, poor phonetic representations of words, and a decreased vocabulary in both languages (Bilingual Children — La Tribu Austin, n.d.). Nonetheless, recent research in the field indicates the opposite, producing discussions of a definitive bilingual advantage in the cognitive executive functions for individuals.

II. Cognition and Executive Functions

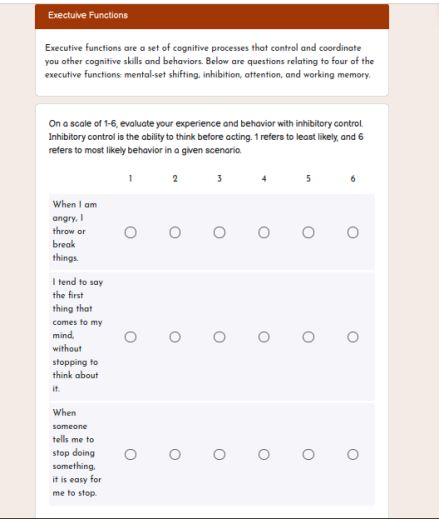

Bilingualism, in the surrounding context of cognition, is not the commonly associated socio-psychological bilingualism, but rather cognitive bilingualism, which refers to the way linguistic systems interact with the neurological systems in an individual. Cognition mostly encompasses intelligence and strategic thinking, problem solving, control of processing, and metalinguistic awareness (Mishra, 2018; Molnar, 2021). As part of our cognitive abilities, executive functions are the most widely used set of skills, entailing inhibition, mental set shifting, working memory and attentional control.

Inhibitory control indicates the capability to control automatic urges by employing rationality, while attention is an individual's capacity to select what they pay attention to. Similarly, mental shifting cites the ability to regularly switch between alternating tasks or mental sets, and working memory is the capability among individuals to retain temporary information (Molnar, 2021). These skills are prominently researched in bilinguals because the constant switching between languages in daily situations is maintained by the active use of these functions in the cerebral cortex. The cortex—present on top of the cerebrum in the brain—carries out essential functions such as thinking, learning, reasoning, consciousness, and sensory functions while housing these functions as well (Molnar, 2021).

III. The Bilingual Advantage

The advantage of bilingualism on cognition is defined as the greater ability of bilinguals to regulate their executive functions, shaped by the prolonged use of their second language. The frequent operation of another language leads to a constant need for interference suppression—to use only one language at a time while blocking the other in response-demanding situations—yielding better inhibitory control for bilinguals compared to monolinguals (Bialystok, 2022).

Additionally, regular switching requires equal processing and managing for both languages. This, when carried out on an everyday basis, produces strong neuroplasticity in bilinguals, and these strong neural pathways eventually strengthen working memory capacity, especially the visuospatial component in the cortical region: the mainly initialized part of working memory in terms of better speed, accuracy, and update of information (Liu, 2021).

Not only does bilingualism enable individuals to store a greater range of word recognition details for both languages, but it also allows for enhanced attentional control when faced with tasks that require conflicting response demands. Stemming from the advanced experience of bilinguals in controlling their two languages in the same modality, such conflict-monitoring processes connect to greater mental-set shifting in the brain, which signifies the most noteworthy measure of cognitive flexibility (Bialystok, 2022; Xie & Zhou, 2020).

IV. Bilingualism in older adults

Research on older adults has shown that bilingualism leads to the maintenance of consistent patterns of reading, verbal fluency, and general intelligence, indicating it as a protective factor against cognitive decline and dementia, as the neural pathways that consist of these aspects are permanently preserved with a frequent second language use (Bak, 2014; Ballarini et al., 2023). More specific reasons for such delayed onset of cognitive decline conditions in older adults is hypermetabolism and decreased brain atrophy. Hypermetabolism refers to the excessive consumption of glucose in bilinguals to maintain the same amount of brain pathology as monolinguals. Such processes, when performed throughout lifetimes, lead to decreased neural loss, or in other words, decreased brain atrophy, hence preventing earlier diagnosis of dementia (Costumero, 2020).

Despite these promising effects against cognitive aging in adults, there are several factors that may affect these benefits, such as the age the language was acquired, and childhood IQ. Furthermore, the advantages of bilingualism do not stem from the mere knowledge of a second language, but from its frequent use and switching which demands a high cognitive control to inhibit potential interferences between languages. Such cognitive control is what strengthens the neural pathways, leading to protection in older adults. Therefore, early vs. late acquisition, frequency of usage, and childhood Intelligence Quotient all collectively impact advantages of bilinguals against dementia (Bak, 2014; Ballarini et al., 2023).

V. Gap, Hypothesis

My gap addresses how bilingualism affects adolescents, as most studies have focused only on infants (early word recognition patterns) or older adults (studying the delays in the onset of dementia). Based on background research, I expect the results to narrate a bilingual advantage through better scores in executive function for bilinguals than monolinguals. Regardless, there is also a possibility of reaching null results, since some limiting factors may produce bias and potentially alter results.

Methods

Design

Because of the nature of my study, I practiced primary research, considering I collected the data myself. This led to an explain approach as I was explaining the connection between executive function scores (inhibition, working memory, attention, and mental shifting) and bilingualism using my data. The overall design type is quasi-experimental, as I used a survey to collect information albeit without a control group and random assignment, as the survey was distributed through the help of teachers in the schools to reach the target age groups.

Method

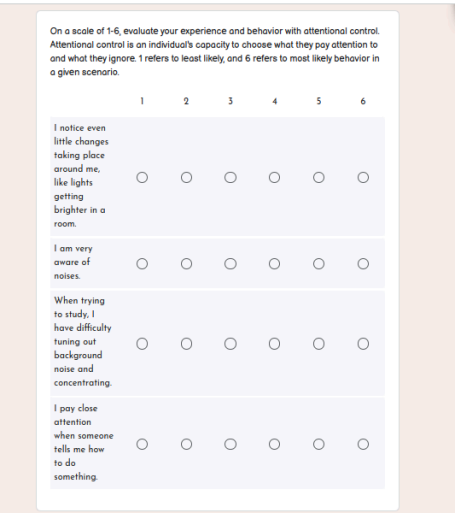

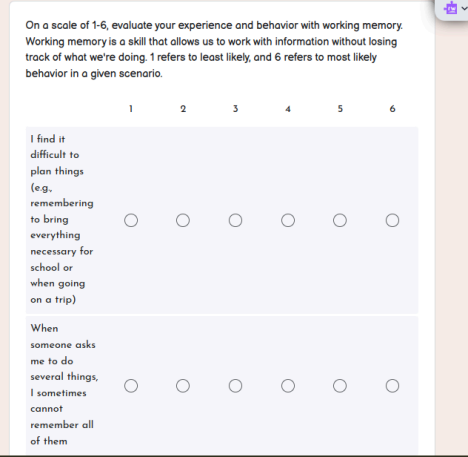

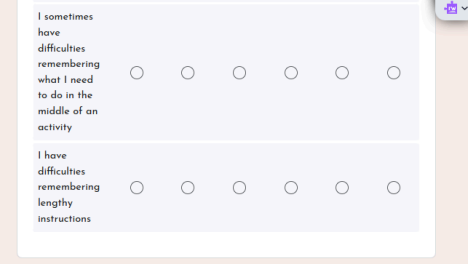

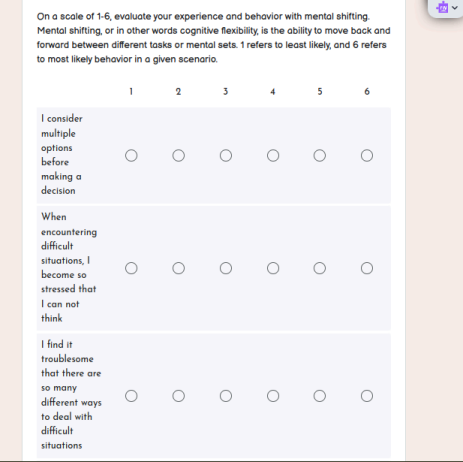

As mentioned above, the experimental design for this research study was quasi-experimental. Moreover, the method of inquiry was a mixed procedure, because I collected both qualitative and quantitative data. The survey gathered numerical, or quantitative, data in the form of executive function scores using a 1-6 likert scale for each behavioral situation. These situations in the survey prompted participants to rate their likely behavior for every daily scenario for the executive functions. Conversely, the relationship of the number of languages spoken to the scores served to be qualitative data. Thus, a mixed method approach justifies the comparison of qualitative factors in dictating the quantitative scores.

Subjects of Study

In this study, the subjects largely researched were adolescents—as mentioned in the gap—of all demographics, ethnicities, genders and socioeconomic status in the age range of 12-18 years. The expected participant responses were approximately 60-90 adolescents. The independent variable of the research was the number of languages spoken by subjects (monolingual or bilingual), while the dependent variable was scenario performance that dictated cognitive advantages based on the number of languages spoken, hence connecting to the main research focus revolving around the impact of bilingualism on cortical executive functions.

Instruments

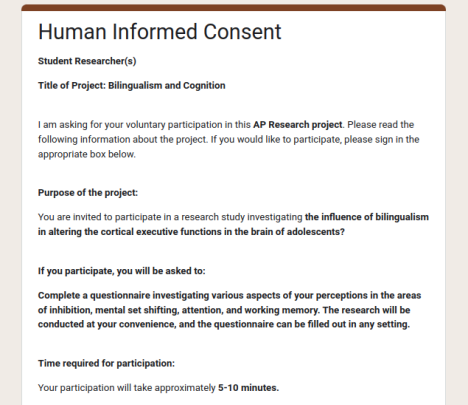

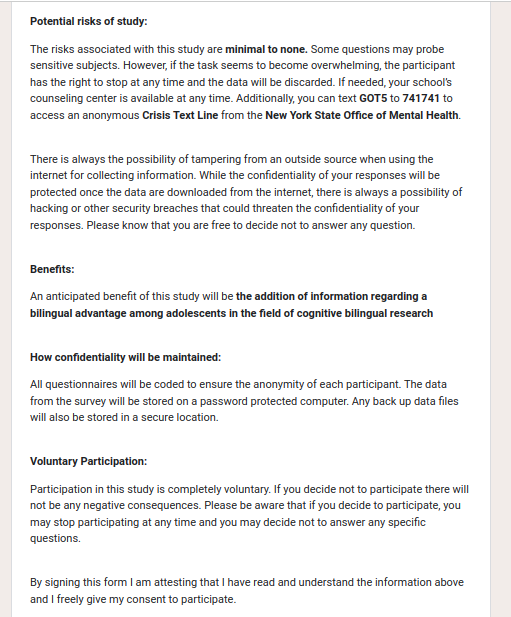

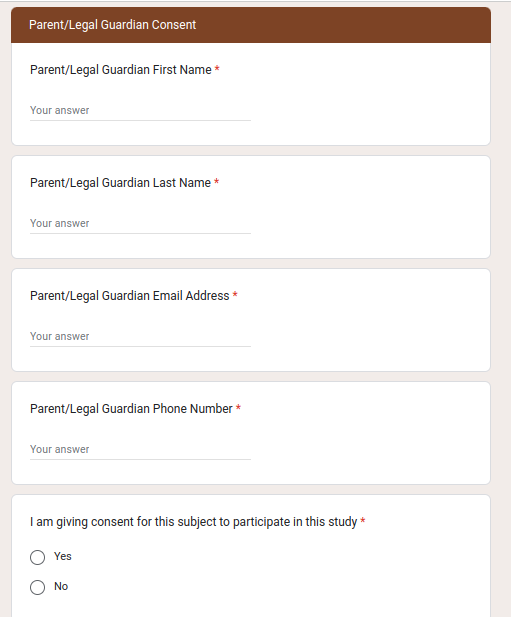

Various instruments were utilized throughout the research to form a cohesive data collection process. A survey (*see Appendix A for survey) created on Google Forms was distributed as the primary mode for gathering data. Google Forms was used as the optimal platform due to its easier accessibility and usage, as well as faster distribution. Additionally, both consent and assent forms (*see Appendix B) were added before the survey in order to comply with the Institutional Review Board’s ethical guidelines, as the participants were mostly minor adolescents. Surveys were also largely distributed, upon the Institutional Review Board’s approval, through collaboration with teachers of classes in the high school and middle school to reach the age range of subjects.

Protocols

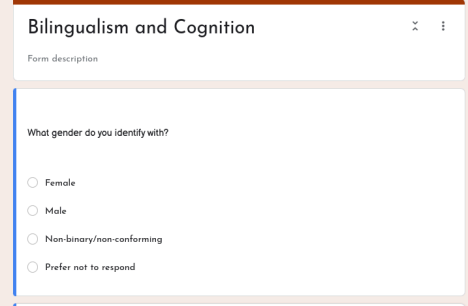

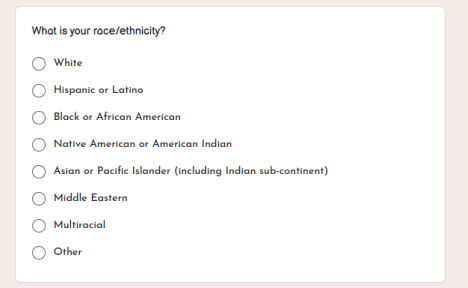

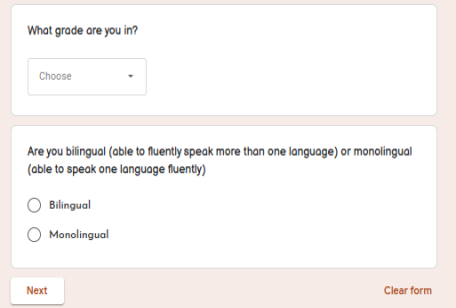

A detailed survey administration process was utilized for efficient distribution and data collection. The steps below outline the main criterion following the consent/assent forms, as well as the information included in the actual survey. Further assessments regarding specific questions of the survey in each category are also included in Appendix B.

1. A consent form is sent through Google Forms to potential subjects of study at the high school and middle school. The first page lists the guidelines, descriptions, and purpose of the study, as well as available contacts (State Mental Health Office, Crisis Text Line) if assistance is needed at any point of participation.

2. The next page in the form outlines parental consent, the questions of which include parent/guardian name, email, phone number etc. Such data were necessary to maintain ethical considerations, and was not used in any form for data analysis.

3. The following page asks for individual assent, where the student attests to voluntary participation. If BOTH consent and assent are received, the individual receives a link to the actual survey upon submission.

4. The pre-questions in the survey prompt the participants’ demographics, age, ethnicity, gender and the number of languages spoken by them. These questions are added as independent variables that could dictate qualitative aspects of the findings and analyses.

5. Then, in the next section, the executive functions are divided into four categories of scenario-based questions: inhibition, working memory, attention, and mental shifting, respectively.

Limitations

Although the procedure of data collection and analysis had minimal obstacles, some limitations occurred when conducting the research. For example, since my survey was reliant on truthful recollection from participants on their behavior, false answers resulted in no definite relationship between bilingualism and cognition. This could mainly occur due to non-response bias: a psychological phenomenon where individuals may answer according to their perception of the desired results instead of honest responses.

Furthermore, the questions in my survey pose a lot of subjectivity for individuals. For example, for the inhibition question, “Do you throw or break things when you’re angry?”a bilingual participant may answer 1 if they believe this behavior never pertains to them. However, a monolingual participant may also answer the same way, if they believe their behavior occurs, but not often enough to account towards 4 or 5 on the scale. Hence, this subjectivity may cause discrepancies in the data regarding what executive functions actually portray bilingual advantages.

Another limitation that stems as a result of the non-response bias is the sample being non-representative of the population. Because of potential inaccuracies in recollection or rating from participants, the results that occur might not apply to the overarching population. Non representativeness is further exemplified due to the survey’s distribution to only one location which may not represent the ideas and demographics of all people, specifically not all adolescents.

Results

Findings and Statistical Analysis

Following several weeks of gathering data, a total sample of 154 survey and consent form responses were received. The results depicted 81 bilingual responses and 73 monolingual responses from an age range of 12-18 year olds. As previously stated, the primary questions answering the research focus revolved around scenario-based prompts for each of the four executive functions of inhibition, working memory, mental shifting and attention. Based on the participants’ rating of their behavior for each situational question on the likert scale (from 1-6), I analyzed the influence of language on cognition, comparing the bilingual scores to the monolingual average responses for all the categories. The following charts illustrate the data collected and examined throughout the course of this research.

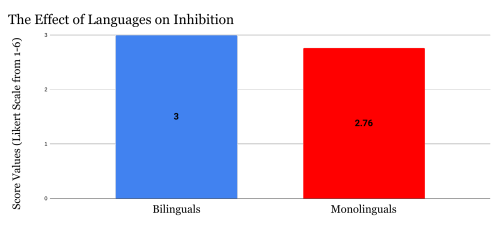

Figure 1: A bar graph comparing the average score responses for the first set of questions involving inhibitory control between monolinguals and bilinguals.

Figure 1: A bar graph comparing the average score responses for the first set of questions involving inhibitory control between monolinguals and bilinguals.

Figure 1 above shows that the mean likert value for bilingual participants was 3.00, while that for monolinguals was 2.76. A two-sample t-test was used to determine if bilinguals had higher inhibition than monolinguals. The results revealed t = 1.788, p = 0.679. This shows that the data is not statistically significant—with a 67.9% probability of the findings due to chance—rendering bilinguals to have lower inhibitory control than bilinguals. Considering that inhibition refers to the control of automatic responses for rationality, lower likert values for this category indicated higher inhibition. For instance, answering more towards 1 on the scale for questions pertaining to volatile scenarios would mean the occurrence of that behavior is rare to none, translating to higher inhibitory control.

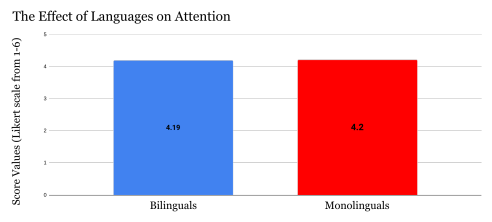

Figure 2: A bar graph comparing the average score responses for the second set of questions involving attentional control between monolinguals and bilinguals.

Figure 2: A bar graph comparing the average score responses for the second set of questions involving attentional control between monolinguals and bilinguals.

Figure 2 above displays that the mean likert value for bilingual participants was 4.19 while that for monolinguals was 4.20. A two-sample t-test was used to determine if bilinguals had higher attention than monolinguals. The results disclosed t = -0.080, p = 0.5317. This acknowledges that the data is not statistically significant—with a 53.17% probability of the findings due to chance—demonstrating bilinguals to have about the same attentional control as monolinguals, not higher.

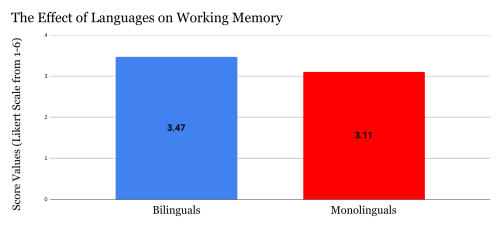

Figure 3: A bar graph illustrating the average score responses for the third set of questions involving working memory between bilinguals and monolinguals.

Figure 3: A bar graph illustrating the average score responses for the third set of questions involving working memory between bilinguals and monolinguals.

Figure 3 above displays a mean likert value of 3.47 for bilinguals, and 3.11 for monolinguals. A two-sample t-test was used to determine if bilinguals had higher working memory than monolinguals. The results showcased t = 1.804, p = 0.0366. This implies that the data is statistically significant, with a 3.66% probability of the findings due to chance, demonstrating bilinguals to have higher working memory capacities than monolinguals on tasks requiring the retention and manipulation of information.

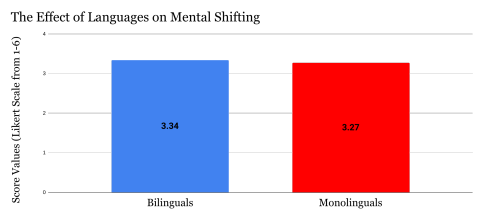

Figure 4: A bar graph showcasing the average score responses for the third set of questions involving working memory between bilinguals and monolinguals

Figure 4: A bar graph showcasing the average score responses for the third set of questions involving working memory between bilinguals and monolinguals

Figure 4 above displays that the mean likert value for bilingual participants was 3.47, compared to the monolinguals’ average of 3.27. A two-sample t-test was used to determine if bilinguals possessed greater mental set-shifting abilities than monolinguals. The results portrayed t= 0.393 p = 0.3473, describing that the data is not statistically significant—with a 34.73% probability of the findings due to chance—narrating bilinguals to have higher working memory capacities than monolinguals, and showing a direct relationship.

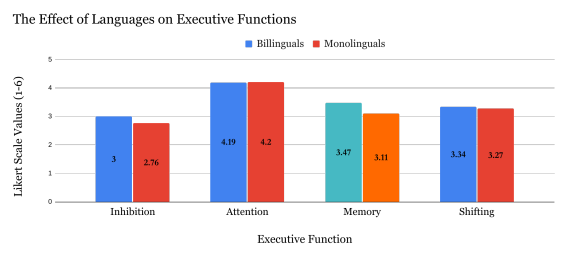

Figure 5: A bar graph displaying a summary of all the mean scores for each executive function.

Figure 5: A bar graph displaying a summary of all the mean scores for each executive function.

After comparing the average ratings for all functions, it is observable that working memory was the sole function with a significant difference between its bilingual and monolingual scores, as seen from the highlighted regions in Figure 5, causing it to be statistically significant in determining greater cognitive development for bilingual advantages. Although inhibition and shifting also possess higher average values, they are not statistically significant, as shown from the p-values from the analytical t-tests.

Analysis

As a result of quantitative data collected in the form of average behavioral values, and qualitative data gathered from illustrations of graphs comparing the effect of languages on cognitive functions, the method of research followed a mixed methods approach. This allowed for the triangulation of data for an enhanced understanding of the research focus through multiple perspectives on the same phenomenon.

Overall, the data displayed statistical significance for working memory (3.66% probability of chance), corresponding to higher values for bilinguals in that category than monolinguals. While most of the functions were measured through direct proportionalities to the likert value ratings, the graph for inhibitory control portrayed an indirect relationship, showcasing lower average scores for monolinguals that translated to greater inhibition.

The statistical analysis conducted through 2 sample t-tests for each variable substantiated the research question, providing data on the influence of bilingualism. Although the expected outcome hypothesized increased efficiency in cognitive performance for bilinguals in all the executive functions, the results supported such effectiveness for working memory only, leading to only part of the expected outcome corroborated. This outcome aligns with previous research on the visuospatial components of working memory that concluded greater capacities for bilinguals (Liu, 2021). However, it raises questions about the implications of executive functions like inhibition, attention and shifting holding true for the neural pathways of older adults, contrary to predictions from prior studies (Costumero, 2020). The aforementioned research on older adults concerning bilingual advantages displays lower cognitive declines if neuroplasticity among all executive functions is maintained. But, with

other factors such as age of acquisition, and childhood IQ also impacting prolonged nerves, advantages from just one function of working memory might not be sufficient to preserve neural pathways, refuting the stated understanding (Bak 2014; Ballarini 2023). In conclusion, my new understanding is that bilingualism presents higher executive functions for only working memory, opposing initial assumptions.

Limitations

When analyzing the data collected, there were some limitations I came across in the process. I noticed that a significant number of responses for a few questions in each category were left unanswered. While participants were not obligated to answer the entirety of the survey, as mentioned in the consent and assent forms for ethical guidelines, blank behavioral ratings may have potentially skewed the results, leading to an unequal comparison basis in terms of the number of responses available for bilinguals vs. monolinguals.

Additionally, I was limited in the number of responses received from the younger age group of adolescents (12-13 years). Ideally, I would have liked to showcase findings that pertained to the entire age range of adolescents (12-18 years), but due to the location of the research that posed difficulties in survey administration to the younger participants, I was restricted in my data analysis and responses from 12-13 year olds. These limitations could lead to misinterpreted findings on what executive functions portrayed bilingual advantages.

Conclusion

Summary of Findings

The principal findings of this study were that eventually, bilinguals and monolinguals had approximately the same level of cognitive enforcement, and that the number of languages known created an impact only for the field of working memory. Part of the expected outcome was met—with statistically significant findings of higher memory ranges for bilinguals—but a major portion of the initial hypothesis concerning greater scores for the remaining three executive functions was refuted. These findings were underscored by the two sample t-tests that displayed p-values greater than 0.05 for inhibitory control, attention and mental shifting. In general, the new understanding reflected bilingual prominence in memory components.

As aforementioned, my findings connect to related research surrounding memory and its visuospatial components, with the same conclusion of such greater capacities in bilingual adolescents reached (Liu, 2021). However, in terms of the other cognitive functions, my results do not replicate similar findings, and probe further investigation to determine whether advantages concerning inhibition, attention and shifting in adolescents persist (Bialystok, 2022; Xie & Zhou, 2020).

Despite not achieving the desired outcomes from my initial hypothesis, my gap regarding bilingual advantages in adolescents was addressed through the research process. The findings and analyses from my survey distribution are a result of adolescent participation from both the high school and middle schools. Even with limited responses from the younger subgroup, my results nonetheless reflect the targeted age range of adolescents, hence fulfilling my gap.

Implications

The results of this study can largely be used in the education field. With growing STEM enthusiasm, continuing humanities knowledge serves to not only open means of discovering society’s values, but also enhance one’s forms of communications. With more than a 17 percent decrease in enrollments for language classes recently, the results of this research especially help highlight the importance of dual language education, and the numerous benefits associated in the field of cognitive perception (Fischer, 2023). Specifically, continuing bilingualism in younger generations could help with faster acquisition—due to higher neuroplasticity—which in turn could boost mental flexibility. Additionally, these results could be used for psychological purposes as well. Since my primary research focus revolved around the cortical executive functions—the results of which can narrate bilingual advantages—studying them in depth could reveal more about the brain’s overall structure, with emphasis on how it functions in bilinguals compared to monolinguals and whether there exist any differences in form for the two groups.

Limitations

While no major obstacles were encountered in the research process, there were still minor limitations that allowed for some inconvenience within the collection and analysis of data. For example, one considerable limitation to my data analysis stemmed from participant bias. Because most of my survey posed subjective scenarios for participants to rate their behavior on, the data from these responses might be skewed due to untruthful recollection. This could then produce non-representative results that might not accurately represent the entire adolescent population. Furthermore, the above stated non-response bias is also compounded by the small location at which the survey was administered. Because of the low level of ethnic diversity, the data is further limited in its validity. Lastly, as mentioned in the Discussion, the small sample of responses specifically from 12-13 year old adolescents serves to restrict the generalizability of the results for a greater population. Although there were responses in general present from this age group, they weren’t significant enough to lead to accurate conclusions.

Further Studies

Upon further reflection on the research and data collection process, it can be concluded that future studies can aid in addressing some of the limitations experienced in this study. Mainly, future research in this field can aim to gather more data from adolescents that avoids restrictions such as non-representativeness and limited location availability. Moreover, future studies can also focus on researching other executive functions present in different areas of the brain. Although my study focused on just the four cortical functions, there exist many more in various regions: like the thalamus, subcortical regions, the putamen, and other lobules. Functions in these areas include aspects of control processing and time management that could be studied. These variables could not be monitored in adolescents, but could also be tested in other age domains like infants and older adults. As seen from previous research in the Review of Literature, bilingualism shows benefits for older adults, in the usage of the four cortical functions, by preventing the onset of cognitive decline and dementia. Further studies about other cognitive factors could explore similar aims, and develop additional knowledge in the field.

In addition, future research could focus on the different variations among bilingual populations, and how this affects cognitive development. For instance, bilinguals in a certain area might be fluent in two languages in terms of both reading and writing (literacy), and speaking and understanding (vocalizations and deep comprehension). Nonetheless, other bilinguals might only be proficient in their second language up to the threshold of speaking and understanding it. Thus, this gap in bilingual literacy could be further explored, showing whether bilingual advantages of inhibition, memory, attention and shifting exist within these groups as well. Similarly, future studies can perform research on the impact of regional dialects on cognitive advancements. With many East Asian languages consisting of multiple dialects, for instance, there may be differences in the degree of bilingualism present that may influence mental processes.

References

Ballarini, T., Kuhn, E., Roske, S., & Altenstein, S. (2023). Linking early-life bilingualism and cognitive advantage in older adulthood. PubMed. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36706574/

Bialystok, E. (2022). The Systematic Effects of Bilingualism on Children's Development. NCBI. Retrieved September 28, 2023, from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5214932/

Bilingual Children — La Tribu Austin. (n.d.). La Tribu Austin. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://latribuaustin.com/bilingual-children

Fischer, K. (2023, November 15). It's a Bleak Climate for Foreign Languages as Enrollments Tumble. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved December 17, 2023, from https://www.chronicle.com/article/its-a-bleak-climate-for-foreign-languages-as-enrollmen ts-tumble

Goldenberg, C., & Wagner, K. (2015). Bilingual Education. American Federation of Teachers. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://www.aft.org/ae/fall2015/goldenberg_wagner

Liu, Q. (2021). A Review on the Relationship between Bilingualism and Working Memory. Scientific Research Publishing. Retrieved September 25, 2023, from

https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=107938

Mishra, R. K. (2018). Bilingualism and Cognitive Control. Springer International Publishing. Molnar, M. (2021, August 26). Measures of Bilingual Cognition – From Infancy to Adolescence. NCBI. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8396129/

Smith, D. G. (2018, May 4). At What Age Does Our Ability to Learn a New Language Like a Native Speaker Disappear? Scientific American. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/at-what-age-does-our-ability-to-learn-a-new-l anguage-like-a-native-speaker-disappear/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7000619/

Appendix A: Survey

Appendix B: Consent and Assent Forms

Document information

Published on 21/10/24

Submitted on 14/10/24

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license