Abstract

We have arrived at a critical juncture when it comes to understanding the numerous ways in which trade interacts with climate change and energy (trade-climate-energy nexus). Trade remains crucial for the sustainable development of the worlds greatest trading nation: China. After clarifying the linkages within the trade, climate change and energy nexus, this article delves into Chinas specific needs and interests related to trade, climate change and energy. Then it explores the ways in which trade can contribute to Chinas needs, to sustainable energy development and to the goals of the global climate agreement that is under negotiation.

One main findings are China is a key participant in negotiations on trade liberalization of environmental technologies and services. These negotiations are in Chinas interests in terms of innovative industries, technological upgrading, employment and public health. China could stand up for the interests of other emerging and developing countries and serve as an example in terms of transitioning to a low-carbon economy. Beyond trade barriers issues of domestic (energy) regulation such as fossil-fuel subsidies as well as investment, competition-policy, trade-facilitation and transit issues related to clean energy need to be addressed.

Building trust between relevant actors across sectors and national borders will be of the essence in order to foster long-term cooperation on technological innovation.

As a way forward, different approaches towards the governance of trade and climate change will be highlighted. Besides discussing the specific aspects of Chinese participation in global trade and climate change governance, this paper aims at offering broader insights into the nexus between trade, energy and climate governance in China.

Keywords

Climate change ; Trade ; Governance ; Sustainable energy goods and services ; Investment ; Emissions trading

1. Introduction: the trade-climate-energy nexus

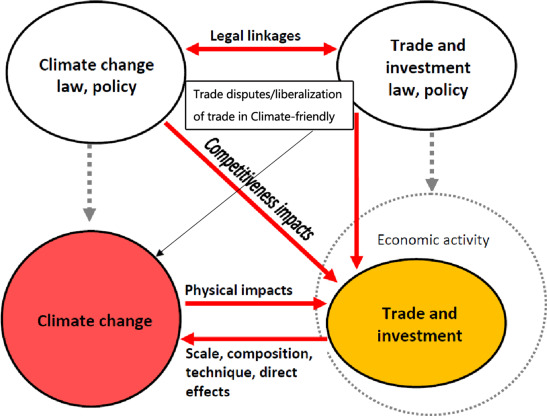

The aim of this article is to explore what contributions trade1 can make to reach the objective of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and other pollution that result from fossil fuel use. The linkages between trade, climate change and energy are intricate and numerous, as a UNEP-WTO report on trade and climate change2 demonstrates. Fig. 1 shows the main linkages between trade and climate change as follows:

- Climate change can have physical impacts on trade, e.g. through changed patterns in agricultural production and impacts on infrastructure such as harbours because of rising sea levels.

- The other way around, trade and economic activity also affect climate change and energy use (through scale,3 composition,4 technique5 and direct6 effects).7

- Then there are the legal linkages between climate change and trade governance, and the competitiveness impacts that these can have, for example when governments put carbon pricing mechanisms in place. In particular developing countries are concerned about climate measures that developed countries can take if those measures affect the exports from developing countries. Therefore both the Kyoto Protocol (in Articles 2.3 and 3.14) and the UNFCCC (in Article 4.8) commit countries to minimize adverse economic, social and environmental impacts on developing countries when responding to climate change (so called response measures).8 Also in the draft negotiating text for COP 20 in Lima there is an option for including an article saying “Unilateral measures are not to constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade.”

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Trade and climate change linkages (Cosbey, 2007 ; black arrow added by author).

|

Although there seem to be few inherent conflicts between climate change and trade policy, in practice specific trade-related policies can be both conflicting and mutually supportive. On the one hand, the number of World Trade Organization (WTO) disputes and other tensions in the area of trade-distortive support for renewable energy has been increasing rapidly, up to the point that some speak of solar trade wars.9 China in particular has been the target of various trade remedies10 because of the ways in which it supported its domestic renewable energy industries (Kasteng, 2013 ). These tensions can damage the solar power industry11 in particular, and they can have an impact on climate change if they continue to hamper the diffusion and development of sustainable energy technologies.12 But fostering trade, for example through lowering trade barriers, can also have a positive impact on climate action. Trade disputes and liberalization of trade related to environmental goods and services (EGS), and more specifically the sub-category of climate friendly goods and services (CFGS, which include mainly renewable energy and energy efficiency technologies) that affect climate change are reflected as the black arrow in Fig. 1 . These specific relations between trade and investment policies reinforce the need to address the overall relation between trade and climate action in a systematic way.

Although the trade and climate regimes have different aims and organization, they do in fact enjoy many common features, as both regimes:

- Aim to promote greater economic efficiency in order to enhance public welfare.

- Recognize linkages between the economy and the environment.

- Look to the future and advocate actions that, while bringing on short-term adjustment costs, anticipate long-run benefits.

- Are worried about free riders and devote considerable attention to securing compliance.

- Have increasingly devolved from the global to other levels and fora. In the face of standstill in the Doha Round, countries have turned from the WTO to bilateral trade agreements and ‘megaregionals’13 in the Transatlantic and Pacific regions. In climate governance, local governments and city alliances14 are stepping up to coordinated governance responses.

- Are deferential to the volitions of developing countries, and follow principles of “special and differential treatment” or “common but differentiated responsibilities”.

- Require a supportive enabling environment based on clear and coherent governance regimes.

Lastly, both regimes are dynamic works-in-progress, continuing institutional improvements during successive negotiations.

Nevertheless, there are also some fundamental differences between both regimes. The climate regime is driven by the need to correct market failure (the impacts of fossil fuels on health and on the environment are currently not priced in). Therefore, governments want maximum flexibility at the national level in using economic instruments to influence individual behaviour. By contrast, the trade regime is not a response to market failure; it is a response to government failure, that is, the distortions of policy fomented by mercantilism and protectionism.

Energy is obviously linked to climate change as the power generation, buildings and transport sectors are major sources of GHG emissions (IEA, 2014 ). Fossil fuel and nuclear feedstock supply for example are very trade intensive, a significant amount of energy is required for producing goods and services that are destined for exports, and energy is needed for enabling trade (e.g. shipping and aviation).

This article is logically structured as follows in order to make it accessible to those who are less familiar with trade (policy) and its relation with climate change and energy. First the article reviews Chinas needs and challenges related to trade, climate change and energy. Then it explores different ways in which trade can contribute to addressing these needs.

Finally, different approaches forward towards more effective governance of the trade-climate-energy nexus will be highlighted.

This section seeks to critically analyse what Chinas goals and needs are for the first part of the 21st century with regards to energy security, environmental sustainability, economic development and employment, technological development and international cooperation all within Chinas wider transition to a low-carbon economy, ecological civilization and a harmonious society within a harmonious world. Chinas rapid economic growth trajectory has dramatically improved standards of living for hundreds of millions of Chinese but it has also come at a considerable environmental cost.15 Demand for water, energy and land now greatly outstrip their sustainable supply; desertification and flooding follow patterns of intensive urbanisation and deforestation; and water and air pollution are the result of rapid industrialisation and slow-to-catch-up (enforcement of) environmental regulations.

In response to some of these concern, and Chinas rising GHG emissions in particular, President Xi announced after the 2014 APEC Leaders' Summit that by the year 2030 at the latest, China will peak its emissions of GHGs and source 20% of its total energy use from non-fossil sources.16 Shortly after that Chinas National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) confirmed that a national Emission Trading System (ETS) will be introduced in China in 2016, and that the carbon market should be fully operative by 2020.17

In order to achieve these targets, seven major needs are identified here that determine decisions on climate change, trade and energy in China:

2.1. Chinas energy needs

The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts China to account for 30% of the non-OECD increase in global energy demand by 2035 as China seeks to maintain its economic development path and improve the living standard for its population. The consulting company Cambridge Energy Research Associates (2014) expects that Chinas total energy demand will double over the next twelve years despite large gains being made in terms of overall energy efficiency.

2.2. Environmental and health needs

Chinas carbon emissions are projected to grow significantly until 2030, the year that China has pledged to let its carbon emissions peak in the deal that was reached with the U.S. in November, 2014. The generation of power accounts for 50% of all Chinese CO2 emissions. Currently around 80% of all Chinese electricity is generated from coal-based sources. The good news is that coal consumption in China has decreased in 2014 (Greenpeace, 2014 ).

Renewable energy has in many cases a high price relative to conventional fossil fuels. This is partly due to the non-pricing of negative environmental and health externalities associated with the use of fossil fuels. The playing field in favour of sustainable energy is further tilted by the almost US$2 trillion in subsidies that are provided to fossil-fuels (IMF, 2013 ).

China is also not immune from the impacts of climate change; powerful examples of the impacts of climate change in China are Himalayan glacier melting and desertification. Approximately 30% of Chinas land surface is desert, and the Gobi Deserts surface area expands by 3600 km2 each year, despite efforts such as the Green Wall of China.18

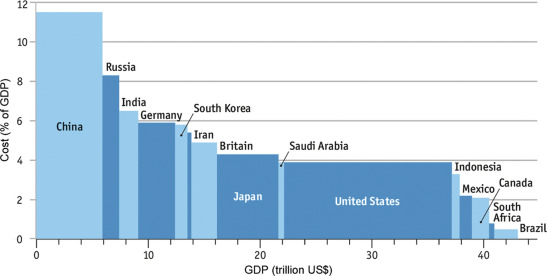

Many of Chinas environmental challenges have been exacerbated by industrial activity related to coal use, Chinas main source of GHG emissions. Coal mining in China has caused considerable damage to the surrounding environment. It has damaged groundwater systems, caused geological disasters and has encountered frequent collapses and other industrial accidents (Pan, 2010 ). The water pollution that results from coal use in China is adding further strain to threatened river systems, further exasperating water scarcity. In 2013, 92% of the Chinese cities failed to meet national ambient air quality standards. This leads to major costs in terms of human health and lives (Fig. 2 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 2. The cost of mortality from PM2.5 exposure (NCE, 2014 ).

|

Many environmental problems in China are related to exports. For example, one-third of Chinas emissions are the result of the manufacturing of exported goods (Weber et al., 2008 ). One reason for this is that Chinas exports are particularly carbon intensive. Whereas Chinas exports produce 2.16 kg of carbon per US$ of exports, the world average is 0.61 kg of carbon per US$ of exports (Jakob et al., 2011 ).

2.3. Chinas employment needs

With large portions of Chinese employment focused on manufacturing and construction, there remains a key problem in the composition of Chinas emerging labour market. China currently produces vastly more university graduates than the number of high-skilled job openings. About 7 million university graduates entered the Chinese workforce each year. Many of these graduates are either unable to find permanent employment or are unwilling to do low-end work. Moreover, the labour cost is rising fast, especially in east coastal regions that were traditional stronghold of low wage and export oriented industries. To meet the needs of its population, the Chinese economy must move up the value-chain in manufacturing as well as services. This need will currently not be met by merely scaling up production and installation of existing technologies. Therefore, the Chinese economy needs to create more jobs in strategic industries,19 many of which are related to low-carbon development.

The structural change that is involved in such a transition to a low-carbon economy could potentially affect millions of Chinese workers. In order to smoothen the transition to a low-carbon society, it needs to be acknowledged that some industries will experience declines in employment—that of coal, cement, and steel—face significant job losses. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that the closure of small coal-power plants will affect over 600,000 Chinese workers between 2003 and 2020. However, if China is able to efficiently ensure these structural shifts, it is expected that 1 million jobs will be created between 2005 and 2020 through the development of low-carbon industries, resulting in a net addition of 400,000 jobs (ILA, 2011 ). Estimates suggest that by 2030, 20 million people could be employed globally in the renewable energy sector, either directly or indirectly. Overall, solar PV offers about eight times more jobs per megawatt of average capacity than a coal-fired power plant (Wei et al., 2010 ). In order to turn the challenges faced by the transition from coal and other old energy sources to new energies into a major economic and social opportunity, major efforts are required in terms of retraining and education of workers, and few countries are as well placed as China is to make this transformation20 .

2.4. Chinas technology and innovation needs

While the low carbon sector is potentially worth considerable amounts of capital,21 it is highly dependent on the continued innovation and implementation of environmentally friendly technology and services within a sound regulatory framework. There is a need for a developing country to grasp the late-mover advantage, so as to benefit from new technologies, trade and the transfer of manufacturing. This allows developing countries to leap-frog their developed counterparts, thus allowing for similar levels of GDP growth with fewer resources. This, however, is easier said than done. Many of the more advanced technologies remain expensive for China, especially for underdeveloped rural regions. Nonetheless, Beijing has made clear that any future developments on trade in low-carbon technologies must take into consideration Beijings policy of indigenous innovation (Tyfield and Wilsdon, 2009 ).

As China exhausts the low-hanging fruit of emission reductions, there will be the inevitable and fundamental need for more sophisticated technologies to restructure the economy through increased energy efficiency and greater utility of low-carbon sources of energy. One priority area is the development of smart grid technology as the renewable energy rich regions (in terms of wind-speed and sun-cover) are located in West and Northwest China which need to carry energy to the energy-intensive eastern coastal regions. It is a well-established fact that many Chinese wind farms that are operational cannot deliver power to consumers due to weaknesses in energy infrastructure and the inability to connect to the grid. To deliver wind-, hydro- and solar-generated electricity to consumers, innovations are required in smart grid technology and energy storage technologies.

2.5. Chinas need for investment

There are considerable levels of investments needed to meet Chinas growing energy demand regardless of Chinas climate change policy. Investment in clean energy in 2013 measured US$56 billion in China, which is the highest in the world (UNEP, 2014a ). But China will have to spend almost 4 times that amount by 2020 to meet its carbon intensity cut and low-carbon energy targets. (TCG, 2013 )

2.6. Chinas need for international cooperation

China has emerged as the global leader in terms of capacity and manufacturing of renewable energy products through huge investment and development incentives. The continued development of these strategic industries will have significant implications for trade and innovation in renewable energy technologies. China, in order to be able to justify its self-proclaimed peaceful rise, has to convince others that it is a responsible member of the international community.22 For most developing and emerging nations, merely complying with international rules and norms would be sufficient. Recent efforts show that China is willing to support other developing countries in addressing climate change. Any move towards sustainable energy sources that are domestically generated could greatly improve Chinas energy security for its domestic economy as well as strategic relations with its regional and international partners. Stronger cooperation between China and the rest of the world on global energy issues, for example through multilateral initiatives for collaboration on low-carbon energy technologies,23 is vital to addressing key global energy and natural resource challenges.

2.7. Chinas need for trade and access to markets

China has become the worlds largest exporter, and the country with the largest GDP in the world (IMF, 2014 ). Beyond exporting manufactured goods, China itself is developing a particular interest in exporting services, its exports of services having grown at over 18% per annum over the last decade. Current negotiations on the plurilateral Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) and negotiations on the Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA) could provide for a framework for the massive scale up of both trade in services related to sustainable energy. China is not (yet) a member to the TiSA negotiations, even though it has shown its interest in joining the talks.

As Chinas economic and developmental transformation has depended on an open multilateral trading system, it has a vested interest in preserving it. What has changed, however, is that China is now an active player in the negotiation process (Mattoo and Subramanian, 2011 ). If China, as well as other emerging economies, is going to actively participate in a process that prevents export protectionism, encourages the liberalisation of goods and services as well as opens government procurement markets then it must be done in such a way that promotes its continued economic growth and sustainable development. For these reasons, an open multilateral trading system remains crucial to China.24

3. The contribution of trade to climate action and sustainable energy

“Therefore, as part of the Sustainable Development Goals, we must promote policy coherence between the economic, financial and trade systems and environmental sustainability, including the climate change agreement.”

This quotation from Ban Ki-Moon shows that the current UN Secretary-General thinks that trade is important for sustainable development, and for climate change in particular. A recent cost-benefit analysis indeed reveals that trade can make phenomenal contributions to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals. (CCC, 2014 ) The Paris Agreement can be expected to include clear linkages to the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals.25 At the time of writing, draft SDG number 13 is “take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts” and SDG number 7 is “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”.

Earlier policy statements and international agreements have already reflected the need for trade governance to be part of such a coherent governance regime. The Rio Declaration of 1992, the preamble to the Marrakesh agreement and the outcome of Rio+20 Conference recognized the contribution of trade and the multilateral trading system to sustainable development. This section will look into the different ways in which trade can support climate action.

3.1. Trade in climate-friendly goods and services

3.1.1. Background

The environmental-social-economic win-win-win situation of trade in environmental goods and services (EGS) is typically given as the prime example of how trade can contribute to climate action and sustainable development in general (WTO and UNEP, 2009 ). Trade and investment play an increasingly important role is the development and diffusion of CFGS. In fact, trade and investment are the main drivers behind clean technology transfer, and they can contribute to a competitive but also collaborative environment which builds trust between companies and countries, and in which consumers are supposed to get higher quality, more innovative products at lower prices.

The size of the global market for environmental technologies is expected to amount to about US$2 trillion by 2020 (UNEP, 2013 and UNEP, 2014b ), and a major part of that market can be linked with sustainable energy. Trade and investment allow for comparative advantages to be exploited and for global competition which has proven to drive prices of sustainable energy down.

3.1.2. Recent developments

In the Doha Ministerial Declaration of 200126 , WTO Members gave the mandate to negotiate the liberalization of trade in EGS. Due to several technical reasons such as the challenge to define environmental goods, and because of the general slump in the Doha Round negotiations, it was difficult to finalize the EGS negotiations at the global level. This changed when APEC-economies announced27 in November 2011 that they would develop a list of environmental goods, on which applied tariffs should be reduced to 5% or less by the end of 2015. In the same declaration, APEC economies announced that they will “eliminate non-tariff barriers, including local content requirements that distort environmental goods and services trade.” In September 2012, the APEC member economies indeed agreed to a list of environmental goods, covering 54 tariff lines.

Soon after, in June 2013, the U.S. issued the Climate Action Plan, which included a clear commitment for an EGA. The EGA could be a stand-alone plurilateral agreement similar to the successful Information Technology Agreement (ITA),28 which is currently being updated at the WTO after the U.S. and China agreed on a list of goods at the 2014 APEC Summit.

3.1.3. The rational behind and overage of the EGA

In the joint statement regarding trade in environmental goods29 that announced the EGA negotiations the Friends of EGS say that “one of the most concrete, immediate contributions that the WTO and its Members can make to protect our planet is to seek agreement to eliminate tariffs for goods that we all need to protect our environment and address climate change”. They further see this effort in the WTO as an important contribution to the environmental and climate change agenda, and to the transition to a Green Economy.30

The statement thus explicitly mentions the removal of tariff barriers, but it also opens the door to “address other issues in the sector”. These could be non-tariff barriers31 (such as subsidies, government procurement, standards, local content requirements, technology transfer etc.) and barriers related to trade in services.32 Even though China made striking commitments to open its services markets as part of its WTO accession negotiations, some explicit restrictions (e.g., limits on foreign ownership) and implicit impediments (e.g., the exercise of regulatory discretion in financial services and the awarding of licenses) still remain.

Another rationale behind the EGA negotiations is that trade related tensions and indeed trade disputes on issues related to renewable energy have been increasing over the past few years, as countries design and implement industrial policies to spur domestic production of CFGS. Governments often try to combine renewable energy goals with objectives such as stimulating domestic industry and greenjobs, and technological upscaling in what promises to be a growing sector in the 21st century.

3.1.4. The structure of the CFGS industry and impacts of an EGA (including on GHG emissions)

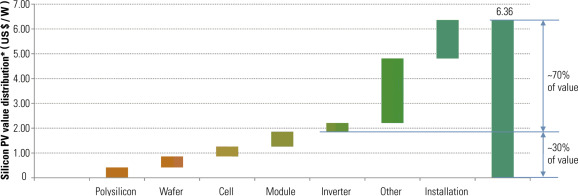

Policies in any country to protect uncompetitive domestic industries from the realities of the global market that we live in today may result in short term profits, or the delay of bankruptcies, but it can be a barrier to robust and efficient global markets which can deliver cheap and innovative forms of clean energy in the long term. The problem is that currently, in many countries the production and diffusion of technologies for non-fossil energy supply and energy efficiency33 is made inefficient by policies and measures affecting trade and investment. In a rapidly integrating world, the CFGS and other technologically advanced industries are typically organized through value chains in which materials, components and technologies from various geographical origins are sourced from and partially processed by a variety of economic agents located in diverse jurisdictions, enabling efficiencies along the entire value chain. One particular issue that policy makers can lose out of sight is the fact that most jobs and added value in value chains of solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies for example are delivered in the installation and maintenance phase, and not in the manufacturing phase of the value chain (Fig. 3 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 3. More than half of the jobs and value generated lie downstream in the US solar PV sector. (CEEW, 2012 ) As the prices of hardware will keep on decreasing, the relative value added in the place of installation can be expected to increase.

|

Because many CFGS are produced in value chains which span several countries, the term Clean Energy Race (between China, the U.S. and European nations in particular) does not do justice to the complex reality of global supply chains. So to speak of goods that are wholly Made in China or Made in the U.S. is misleadingly simplistic (Harder, 2011 ). Although the trade in solar PV products is a seemingly one-way flow from China to the U.S., a value chain perspective reveals that in fact the U.S. has a trade surplus with China in the solar PV sector as it is a main supplier of high-value polysilicon, the raw material used for making PV cells, and of wafers and the capital equipment for solar factories.34

In terms of the impacts of removing import tariffs on EGS, Wooders (2009) demonstrated that the maximum amount of GHG reduction possible from tariff liberalization (using a list of 153 goods proposed in the WTO negotiations on EGS), would be between 0.1% and 0.9% of 2030 total GHG emissions. Jha (2013) calculations show that amongst the countries surveyed, removal of import tariffs on EGs would have the greatest impacts in China in terms of emission reduction (−0.8%) and lowering of electricity prices (−0.3%). Removal of local content requirements (LCRs) would actually increase output, employment, and trade in China and other developing countries such as India and Brazil. The welfare gains that would result from reduced emissions in China through removal of LCRs, import tariffs and feed-in tariffs would amount to more than US$4.5 billion. However, Jha also puts these gains in perspective by pointing out the dramatic effects of the removal of fossil-fuel subsidies, which would lower GHG emissions in China by more than 3.4%. These lowered emissions represent another US$4.5 billion in welfare gains.

Thus, despite all enthusiasm about the prospects for an EGA, it has to be noted that in terms of impacts on GHG emissions and sustainable energy development an EGA is not a panacea. Limiting the most destructive impacts from climate change would require an unprecedented effort in terms of emissions cuts, and a complete overhaul of our economic, social and governance systems, including transformational behavioural changes and the accompanying revaluation of our values and attitudes. Thus, trade regulations are not, and cannot be, a substitute for environmental regulations (Lamy, 2007 ).35 However, what an EGA might do is facilitate alternative or innovative approaches to liberalising sustainable energy goods and services. Moreover, EGA may have a strong systemic impact36 and a symbolical meaning as it shows that the clean tech industry has evolved to a level and scale at which governments consider it worthy of a dedicated global trade agreement.

3.1.5. Chinas role in South–South trade

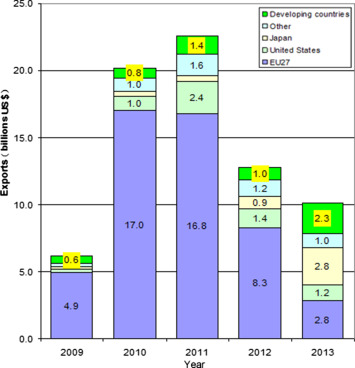

South–South cooperation (that is, cooperation between developing countries), has been rising rapidly in recent years. As exports of PV cells from China to mainly the EU but also the US have decreased because of antidumping and countervailing measures, PV cell exports to developing countries have been growing rapidly (Fig. 4 ). In addition, the Chinese government has encouraged the domestic installation of solar panels at a remarkable speed, aiming at having 100 GW of solar PV capacity in place by 2020.

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Chinese exports of PV cells (national 8-digit tariff line 85414020) by market of destination, 2009–2012 (UNEP, 2014b ).

|

3.2. Standards and labelling

Standards and labelling-schemes represent a measure for countries to realize more ambitious climate goals. Private and public sector actors increasingly make use of non-binding commitments in regards to GHG emissions for different purposes.

From a governmental perspective, voluntary standards can foremost serve to a) foster energy efficiency and b) reduce emission levels while not being regarded as “unjustifiable discrimination between countries”, which is not allowed under WTO rules.

For the private sector, standards and labelling constitute a combined answer to both the call for Corporate Social Responsibility, and the increasing awareness of customers concerning the environmental impact of their purchase decisions. For example, implementing a life-cycle based GHG emissions standard could reduce demand for products that are GHG intensive in both production and use.

Another promising possibility can be the setting of a standard for energy efficiency and the according labelling to indicate the energy efficiency of a product. Chinas greatest potential for energy savings is in ensuring high energy efficiency standards for new construction.

Standards and labelling should be considered valuable tools of climate policy as they can have influence on market penetration and overall environmental effectiveness. The use of voluntary sustainability standards in particular entails several challenges though. Because of varying capability of countries to comply with standards and deliver labelled products to international customers, national producers may suffer disadvantages in trading those products. Especially for developing countries, certain voluntary requirements may become an access barrier to lucrative markets. Moreover standards and labelling are inevitably associated with costs for producers and retailers.

On the other hand, setting international standards on CFGS would provide several benefits. One is trade facilitation stemming from harmonization.37 Another is inducing technological breakthroughs from larger potential markets. Overall, the climate regime has a valid interest in making sure that standards and labels can inform consumers about the ecological footprint of products, with an eye on encouraging both market-based and behaviour-based solutions to climate change.

3.3. Investment, financing and aid for trade

Private investment is pressingly needed to achieve climate-related goals. Incentivizing sustainable energy and infrastructure investments, for instance in public transport networks and efficient buildings, requires a stable investment framework, along with favouring macro-economic conditions such as the availability of skilled workers, existing infrastructure, application of the rule of law, etc. Finance has also been identified as the most important factor in climate technology transfer (UNEP, 2010 ).

The concept of Aid for Trade38 (AfT) and efforts of making developing countries more resilient towards climate change can be related in adaptation and mitigation projects as, for instance, the AfT aim of building economic infrastructure and institutions improves both a countrys ability to trade and its flexibility to shift towards a low carbon economy. A connection between AfT and climate change funds such as the Green Climate Fund would raise the financial opportunities for targets on trade, climate change and sustainable development and create effective synergies. Developing countries could therefore start to request AfT in respect to their trade-related climate adaptation and mitigation measures, and China has an increasingly important role to play in this process as it is rising as a donor of AfT.

3.4. Land use: agriculture and forestry

The Paris Agreement is expected to include a framework for action on deforestation and land use (GA, 2014 ). About one third of global GHG emissions occur due to agriculture and deforestation (CGIAR ). Agriculture and forestry, at the same time, are two of seven sectors (next to fisheries, water supply, human health, coastal zones and infrastructure) considered to be severely affected by climate change. Changing climatic conditions will cause severe losses in crop yields and therefore lead to supply shortages in food products, even inducing hunger crises especially in least developed countries where agriculture and forestry related activities easily account for more than 80% of employment. Food security, trade, livelihoods and long-term development are, thus, directly endangered by climate change. But food production in other countries, such as China and Australia might increase due to changing climates there. Similarly, there may be shifts and greater variation in seasonal food production. This highlights the importance of interregional compensation and the matching of variable food supply and demand through trade.

Given an increasing global demand for food (60% more food will be needed in 2050) and farm products, trade needs to be used for decreasing the carbon footprint of agriculture, Counterintuitively, a favourable geographical location to grow food may have greater advantages in terms of a smaller GHG emissions than the GHG emissions resulting from the international transport of that food. An example that is often given is that it is 4 times more “carbon efficient” to produce lamb meat in New Zealand than in the UK, even when transport from New Zealand to the UK is taken into consideration (Saunders et al., 2006 )39 .

Global forest degradation is responsible for approximately 12–17% of annual global GHG emissions and represents the second largest anthropogenic source of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, after fossil fuel combustion (van der Werf et al., 2009 ). China is the worlds largest importer of illegally harvested timber (Environmental Investigation Agency, 2012 ).

UNEP (2013) illustrates how trade in sustainable forest goods and services is increasingly influenced by national policies, international processes and voluntary procurement practices, e.g., zero deforestation supply chains, which in turn are creating market opportunities for certified producers and traders. One barrier in this field is that sustainable forest products occupy a small share of the global market as it is often difficult to differentiate between products that are produced in a sustainable manner from un-sustainable operations. When there are certification schemes in place, the know-how and cost related to achieve compliance with certification criteria can be another barrier.

3.5. Emissions trading

Emissions trading is considered an increasingly powerful tool to integrate external costs of GHG emissions into economic calculus and thereby reduce the negative impacts of economic activity on climate. The EU started its Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) in 2005, and this remains the biggest carbon trading market in the world. Meanwhile, more than 60 national and sub-national carbon pricing initiatives have been put in place or are planned, including ETS and carbon taxes. It is important also to look at emissions trading because objections against putting an ETS in place are often based on competitiveness concerns: Imports from countries that do not have a carbon price in place are believed to gain an unfair advantage.

Adequately implemented and used, and ETS can deliver a fixed environmental outcome efficiently (at the lowest macroeconomic price) as emission permits are obtained by those who profit most from the emission at the price that represents the economic value of the emission. On the other hand, the most efficient reduction projects are chosen to avoid the acquisition of emission allowances. Carbon trading schemes, as being market-based instruments, do not entail the same disadvantages as carbon taxes (increase in energy prices, uncertainty about the level of tax to attain a GHG reduction goal).

ETS operate flexibly in recession periods and adapt to changing circumstances in an economy, that is, emission prices fluctuate according to the business cycle. Businesses can decide whether to emit and buy the respective permit or implement a project to reduce GHG emissions Cap and trade (maximum total amount of GHG in a given period) therefore incentivizes emission reductions and investment in cleaner technology. As shown in the 2014 Climate Summit in New York, a significant share of private enterprises favour putting a price on carbon.

China is already No. 2 in the world in terms of the size of its domestic emission trading market, having seven pilot emission trading systems in Beijing, Chongqing, Guangdong, Hubei, Shenzhen, Shanghai and Tianjin in operation and planning to initiate a national trading system by 2016, which should be fully operational by 2020.

China in the past has benefitted greatly from the UNFCCCs Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The CDM, under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, allows companies in industrialized countries to buy carbon credits from developing nations in order to comply with requirements to reduce emissions. China has been the single largest recipient, with Chinese companies having sold 229 million metric tons of Certified Emission Reduction credits between 2005 and 2010, equivalent to half the total sold.

One question is how a Chinese ETS could be linked to other systems, such as the EU ETS and the Korea ETS, contributing to larger, more flexible and more robust markets for emissions allowances. Trade policy potentially has an important role to play in governing the linkages of ETSs40 . Creating linkages between national ETS can also resolve the severe problem of “carbon leakage”, which occurs when carbon-intensive companies relocate their production sites/plants in order to avoid ETS and, instead, produce in countries where there is no carbon pricing mechanism in place. This may result in even higher emissions as production may be more carbon intensive in countries with no schemes.

One example of Chinas participation in a global emissions scheme can be found in the aviation sector. After the EU decided in 2008 to include aviation in its ETS,41 and implemented the measure in 2012, there was major resistance from other countries including China. The reason was that China, amongst others, found that taxing emissions in their air space (for example, under the EU ETS, any airline would have to buy emissions allowance for the whole flight from Beijing to London) was a breach of their sovereignty. As a result of the controversy, the EU “stopped the clock” on the inclusion of aviation in the EU ETS and only applies the scheme now to flights within Europe. However, at an International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) meeting in 2013, the EU was able to reach consensus with other ICAO members (including China) on the creation of a global market-based measure for emissions from aviation. This scheme should be agreed upon by the end of 2016, and will enter into force from 2020 onwards. Such a market-based measure (MBM) may have some consequences for trade, as it may make air transport (slightly) more expensive.42 In addition, China has announced that its own domestic ETS will cover the aviation sector.

4. Governance of energy and trade: globally and in China

Previous sections of this article have shown what Chinas needs are regarding trade, climate change and energy, and how trade policies can address those needs. This section will take a closer look at how China is involved in governance of trade, climate change and energy at the international level, and what perspectives Chinas involvement in these issues at the international level offers for the negotiation of, and participation in, related initiatives.

The governance of trade in energy is currently fragmented; diverse institutions are involved in this area of governance, but it is uncertain where the main authority lies both at the domestic and global level.

Addressing the linkages within the trade-climate-energy nexus effectively will require much better domestic coordination between ministries of trade, energy, climate and environment, and preferably also health, finance and infrastructure, and involving not only government but also private sectors and civil society and individual citizens.

Trade in energy falls within the WTOs scope, and the WTO in principle treats energy commodities in the same way as other commodities. The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) is focused on trade and investment in energy. In addition, there are several bilateral agreements on energy and climate change43 that promote trade relations and include approaches to renewable energy promotion and energy efficiency.

A good understanding of relevant public and private bodies and the ways in which they relate to each other is critical for advancing Chinas governance at the nexus of trade and climate change.

The formulation of Chinas climate change negotiating position is influenced by several ministries and administrations, each with varying degrees of influence. The make-up of Chinas negotiating team in international fora is indicative of this confluence of institutional remits. It is the NDRC that heads the delegation (on the vice-minister level) while the lead negotiator is often from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA)s Department of Treaty and Law. In the negotiations, the NDRC and MoFA have the responsibility to ensure that China does not take on any commitments that would be detrimental to Chinas economic development. The policy-making process in the domestic setting is much the same with the process being dominated by the NDRC and MoFA within the National Coordination Committee on Climate Change, and with the Ministry of Environmental Protection being relegated to the second position.

MOFCOM (Ministry of Commerce of Peoples Republic of China) has been designated as the lead agency to negotiate at the WTO and for Chinas preferential trade agreements, including the EGA. Again, given the competitive nature and interests in the political economy that characterizes trade policy, investment and industrial policymaking in any country, in China MOFCOM necessarily has to propel trade liberalization with the consent of all the other ministries with a stake in a Free Trade Agreement before it can submit a negotiation agenda to the State Council for approval.

The task of planning Chinas long-term energy strategy was given to the NDRC as part of the government reorganisation in 2003. In 2008 another round of reforms took place with the creation of the National Energy Administration (NEA) and the National Energy Committee (NEC). The NEA consolidated a number of offices from the NDRC, the existing State Energy Office (SEO) as well as from the Nuclear Power Administration of the Commission of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defence (COSTIND) (Held et al., 2011 : 23–27). The NEA is tasked with managing the energy industry, drafting energy plans and policies, negotiating with international agencies and approving foreign energy investment.

Besides these more bureaucratic actors, and both state-owned enterprises and private companies, new actors such as the mass media, the general public and NGOs have entered Chinas trade and climate change policymaking arena. These actors, usually representing public goods, have long been absent from the negotiating table. But this has had the unforeseen consequence that the decision making process has had to become, at least on the surface, more consultative, open and participatory. The process by which the successive FYPs for example have been constructed is increasingly consultative, incorporating a large number of stakeholders.

5. Conclusion and way forward

This article has shown that Chinas needs in terms of energy security, environmental sustainability, employment, investment and trade are nothing short of astounding. China will need trade and foreign investment (inwards and outwards) to fulfil its needs and address climate change.

China is a key participant in both APECs EGS talks and in the EGA negotiations because of the size of its EGS industry and because of the commitments that China is supposed to make in terms of trade liberalization. It increasingly looks like Chinas interests in terms of innovative industries, technological upgrading, employment and health would be best served in the long term by making trade and access to markets more predictable based on a common understanding of configurations of trade and production of CFGS. In particular, China could ask for clarification of the conditions under which countries can implement trade remedies related to CFGS.

China could further act as a catalyst in the EGA, standing up for the interests of other emerging and developing countries. It could serve as an example for other developing countries in terms of transitioning to a low-carbon economy, thus confirming its role as a constructive and collaborative global partner. Renewable energy trade among developing countries is growing faster than global and north-south RE trade as developing countries, led by China, take advantage of decreasing manufacturing costs, increased investment, and the falling costs of renewables (UNEP, 2014b ).

In order to maximize the benefits from the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA), it is imperative that China joins these talks. To realize this vision, both countries already involved in the TiSA negotiations and China itself should make concessions to bridge the gap on the willingness to dismantle policies that discriminate against foreign service providers in sectors such as financial services, express delivery, telecommunications and audio visuals. What is proposed here in terms of the liberalization of trade in sustainable energy services is a two-stage approach: first more general commitments on services could be included in the TiSA, and these could be worked out in detail in the EGA.

Beyond non-tariff barriers and services, the negotiations could also address issues of domestic (energy) regulation such as fossil-fuel subsidies as well as investment, competition-policy, trade-facilitation and transit issues related to clean energy.

Improved regulation of trade in CFGS could contribute to:

- Levelling the playing field between renewable energy and conventional fossil fuels.

- Benefits for China in terms of energy, trade, technology, environment, creation of policy space, and more predictable trade (less antidumping/countervailing measures).

- Lower tariffs in export markets may not be Chinas first concern; but more predictable access to markets and a framework for a stable environment in which cooperation on innovation and investment can thrive may be more important.

- Enhanced access to foreign clean energy technologies.

- Cleaner air and water as a result of lower fossil fuel use.

- Increased energy independence and energy security.

- Strengthening the image of China as a responsible member of the international community and a constructive partner for other developing and developed countries, for example by reducing deforestation.44

Chinas trade policies need to be not only about securing efficient and functioning markets, but also about addressing trade-related sustainable development concerns and priorities of China as an economy in transition. This also shows the need for building trust between relevant actors, including between private and public sector, and between domestic and foreign companies, in order to foster long-term cooperation on issues such as technological innovation.

Future trade agreements that China will be involved in such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific could offer opportunities for including provisions related to climate change and sustainable energy.

In other words, trade policies should offer the right balance of incentives and guarantees for China and other developing countries to justify the erosion of protection for some of their industries. Therefore, China might wish to include provisions on technical assistance, cooperation or technology transfer.

More work is required in the context of the climate negotiations in order to create synergies in addressing the climate, energy and trade nexus. However, climate negotiators are wary of trespassing their domain and of infringing upon the working area of their colleagues in trade departments and at the WTO. Based on the outcome45 of the Lima COP the most that we can expect to be included in the Paris Agreement is a clause which says that countries cannot take measures that affect trade such as border carbon tariffs on their own (unilaterally), without getting permission from other countries. Based on the potential for trade to contribute positively to climate action as demonstrated in this article, this should be of concern. More explicit language on the ways in which trade can contribute to climate action should therefore be included in the Paris Agreement.

China can be more proactive in promoting better understanding and policy coordination for broader public policy interests by synergizing action on trade, climate and energy from the local to the global level. In addition, greater coordination and cooperation between different government agencies and between the government, private sector and civil society are desirable. As with any major common effort, political will, leadership and the ability to place Chinas concerns holistically within those of the outside world will determine Chinas successful governance and global leadership in the areas of climate change, energy and trade.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank colleagues from the University of Geneva, ICTSD, UNEP, WTO and Zhejiang University for useful insights. This article is based on a case study in his doctoral dissertation on sustainability governance, which will be published as a book in 2016.

References

- APEC, 2011 APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation); Leaders Statement on Environmental Goods and Services; (2011)

- Bajželj et al., 2014 B. Bajželj, K.S. Richards, J.M. Allwood, et al.; Importance of food-demand management for climate mitigation; Nat. Clim. Change, 4 (2014), pp. 924–929

- Borchert et al., 2012 I. Borchert, B. Gootiiz, A. Mattoo; Policy Barriers to International Trade in Services Evidence from a New Database. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6109; (2012) Accessed http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/1813-9450-6109

- CCC, 2014 CCC (Copenhagen Consensus Center); Preliminary benefit-cost assessment of the final OWG outcome; (2014) Accessed http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/sites/default/files/owg_ccc_preliminary_cost-benefit_final_assessment.pdf

- CEEW, 2012 CEEW (Council on Energy, Environment and Water, Natural Resources Defense Council); Laying the foundation for a bright future: Assessing progress under phase 1 of Indias national solar mission; (2012) Accessed http://www.nrdc.org/international/india/files/layingthefoundation.pdf

- CGIAR, 2011 CGIAR; Climate change mitigation and agriculture; (2011)

- Cosbey, 2007 A. Cosbey; Trade and Climate Change Linkages: A Scoping Paper Produced for the Trade Ministers' Dialogue on Climate Change Issues; IISD, Geneva (2007)

- de Melo and Vijil, 2014 J. de Melo, M. Vijil; The Critical Mass Approach to Achieve a Deal on Green Goods and Services: What Is on the Table? How Much to Expect?; (2014) CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP9869

- EIA, 2012 EIA (Environmental Investigation Agency); Appetite for Destruction: Chinas Trade in Illegal Timber; (2012) Accessed http://eia-international.org/reports/appetite-for-destruction-chinas-trade-in-illegal-timber

- GA, 2014 GA (Green Alliance); Paris 2015: Getting a Global Agreement on Climate Change; (2014) Accessed http://www.green-alliance.org.uk/resources/Paris%202015-getting%20a%20global%20agreement%20on%20climate%20change.pdf

- Greenpeace, 2014 Greenpeace; Chinas Coal Use Actually Falling Now (For the First Time This Century); (2014) Accessed http://www.greenpeace.org.uk/newsdesk/energy/data/chinas-coal-use-actually-falling-now-first-time-century

- Harder, 2011 A. Harder; Is America Losing the Clean Energy Race? National Journal; (2011) Accessed http://energy.nationaljournal.com/2011/10/is-america-losing-the-clean-en.php

- Held et al., 2011 D. Held, E. Nag, C. Roger; The governance of climate change in China. LSE-AFD Climate Governance Programme, Working Paper WP 01/2011; (2011)

- ICTSD, 2014 ICTSD (International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development); Linking Emissions Trading Schemes: Considerations and Recommendations for a Joint EU-korean Carbon Market; ICTSD, Geneva (2014)

- IEA, 2014 IEA (International Energy Agency); World Energy Outlook 2014; (2014)

- ILA, 2011 ILA (International Labour Office); Skills for Green Jobs, a Global View: Synthesis Report Based on 21 Country Studies; (2011) Accessed http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-dgreports/–-dcomm/–-publ/documents/publication/wcms_159585.pdf

- IMF, 2013 IMF (International Monetary Fund); IMF Calls for Global Reform of Energy Subsidies: Sees Major Gains for Economic Growth and the Environment; (2013) Accessed http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2013/pr1393.htm

- IMF, 2014 IMF (International Monetary Fund); World Economic Outlook: Legacies, Clouds, Uncertainties; (2014) Accessed http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2014/02/

- Jakob and Marschinski, 2011 M. Jakob, R. Marschinski, M. Hubler; Between a Rock and a Hard Place: A Trade Theory Analysis of Leakage under Production- and Consumption-based Policies; (2011) Accessed http://www.pikpotsdam.de/members/jakob/publications/leakage-bta-paper

- Jha, 2013 V. Jha; Removing Trade Barriers on Selected Renewable Energy Products in the Context of Energy Sector Reforms: Modelling Environmental and Economic Impacts in a General Equilibrium Framework; ICT SD, Geneva (2013)

- Kasteng, 2013 J. Kasteng; Targeting the Environment: Exploring a New Trend in the EUs Trade Defence Investigations; National Board of Trade, Sweden (2013)

- Lamy, 2007 Lamy; Doha could deliver double-win for environment and trade; (2007) accessed https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/sppl_e/sppl83_e.htm

- Mattoo and Subramanian, 2011 A. Mattoo, A. Subramanian; A China Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations, Working Paper1 1–22; Peterson Institute for International Economics (2011)

- NCE, 2014 NCE (New Climate Economy); Better Growth, Better Climate. The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate; (2014) Accessed http://newclimateeconomy.report/TheNewClimateEconomyReport.pdf

- Ng and Mabey, 2011 S.W. Ng, N. Mabey; Chinese Challenge or Low Carbon Opportunity? Third Generation Environmentalism; (2011) Accessed http://www.e3g.org/images/uploads/E3G_Chinese_Challenge_or_Low_Carbon_Opportunity_updated.pdf

- Pan, 2010 J.-H. Pan; Low-carbon Logic. China Dialogue; (2010) Accessed http://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/3927

- Saunders et al., 2006 C. Saunders, A. Barber, G. Taylor; Food Miles: Comparative Energy/emissions Performance of New Zealands Agriculture Industry; AERU Research Report No. 285 Lincoln University, Lincoln, New Zealand (2006)

- TCG, 2013 TCG (The Climate Group); Shaping Chinas Climate Finance Policy; (2013) Accessed http://www.theclimategroup.org/_assets/files/Shaping-Chinas-Climate-Finance-Policy.pdf

- Tyfield and Wilsdon, 2009 D. Tyfield, J. Wilsdon; Low Carbon China: Disruptive Innovation and the Role of International Collaboration; Discussion Paper 41 China Policy Institute, Nottingham (2009)

- UNEP, 2010 UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme); Patents and Clean Energy: Bridging the Gap between Evidence and Policy; (2010)

- UNEP, 2013 UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme); Green economy and Trade-trends, Challenges and Opportunities; (2013) Accessed http://unep.org/greeneconomy/GreenEconomyandTrade/GreenEconomyandTradeReport/tabid/106194/language/en-US/Default.aspx

- UNEP, 2014a UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme); Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2014; (2014) Accessed http://www.unep.org/pdf/Green_energy_2013-Key_findings.pdf

- UNEP, 2014b UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme); South-south Trade in Renewable Energy: A Trade Flow Analysis of Selected Environmental Goods; (2014) Accessed:http://apps.unep.org/publications/index.php?option=com_pmtdata&task=download&file=-South-South%20trade%20in%20renewable%20energy:%20a%20trade%20flow%20analysis%20of%20selected%20environmental%20goods-2014South-South%20Trade_1.pdf

- van der Werf et al., 2009 G.R. van der Werf, D.C. Morton, R.S. DeFries, et al.; CO2 emissions from forest loss ; Nat. Geosci., 2 (2009), pp. 737–738

- Weber et al., 2008 C.L. Weber, G.P. Peters, D. Guan, et al.; The contribution of Chinese exports to climate change; Energy Policy, 36 (9) (2008), pp. 3572–3577 Accessed http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421508002905

- Wei et al., 2010 M. Wei, S. Patadia, D.M. Kammen; Putting renewables and energy efficiency to work: How many jobs can the clean energy industry generate in the US?; Energy Policy, 38 (2010), pp. 919–931

- Wooders, 2009 P. Wooders; Greenhouse Gas Emission Impacts of Liberalizing Trade in Environmental Goods; IISD, Geneva (2009)

- WTO and UNEP, 2009 WTO (World Trade Organization), UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme); (2009) Trade and climate change WTO-UNEP report. Accessed http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/trade_climate_change_e.pdf

Notes

1. In this article, trade is understood to be international trade: the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories.

2. http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/trade_climate_change_e.pdf .

3. More efficient allocation of resources within countries shifts out the global production possibilities frontier, raising the size of the industrial pollution base, resulting in greater global emissions other things being equal.

4. The composition effect measures changes in emissions arising from the change in a countrys industrial composition following trade liberalization. If, for example, liberalization induces an economys service sector to expand and its heavy industry to contract, the countrys total emissions will likely fall since the expanding sector is less emission intensive.

5. The technique effect refers to the numerous channels through which trade liberalization impacts pollution through changes in the stringency of environmental regulation in response to income growth or the political climate surrounding regulation. The technique effect also includes technology transfer facilitated by trade.

6. Direct effects include emissions and environmental damage associated with the physical movement of goods between exporters and importers, resulting for example from transport.

7. Although the optimistic focus in this article is that we can use trade as a tool for addressing climate change, at this point the disclaimer should be included that trade has until now been a major driver of the rise in consumption and in emissions. However, it would be unrealistic to expect that either governments or companies will voluntarily put measures in place that will sacrifice trade or for that matter (short term) economic growth for the sake of climate change mitigation, however desirable that may seem in the eyes of some observers.

8. http://unfccc.int/cooperation_support/response_measures/items/4294.php .

9. Also see http://www.pv-tech.org/topics/solar_trade_war for a timeline of events.

10. Trade remedies include antidumping measures and countervailing measures.

11. In China, ahead of the trade disputes over solar panels, there was overproduction in the Chinese solar industry already and prices were under pressure. Once the trade disputes started, the pressure on Chinese solar manufacturers to reorganize increased further. In a noteworthy turnaround, the Chinese government adapted its support for domestic generation of solar power and China has shifted from exporting 90% of the panels that it produced in 2012 to installing one-third of all solar capacity in the world in 2013.

12. Technologies here includes goods, services and intellectual property.

13. http://forumblog.org/2014/07/trade-what-are-megaregionals/ .

14. Examples are ICLEI (http://www.iclei.org/ ) and the C40 (http://www.c40.org/ending-climate-change-begins-in-the-city ).

15. Chinese PM Li Keqiang has in this context stated that “we will resolutely declare war against pollution as we declared war against poverty”. http://www.reuters.com/assets/print?aid=USBREA2405W20140305 .

16. This target means that the share of Chinas energy consumption from low-carbon sources would have to reach about 20 percent of total consumption by 2030. This would require China to develop up to 1000 GW of renewable energy and nuclear plants. In addition, China and the U.S. also agreed to strengthen joint institutions and cooperation on climate change and clean energy, including further work through the U.S.-China Climate Change Working Group (CCWG) and a joint Clean Energy Research Centre (CERC). The US will also undertake a number of additional projects to promote Chinas energy efficiency and renewables goals, including further cooperation on “smart grids” geared towards the cost-effective integration of renewable energy technology.

17. For the Chinese press release, see http://www.gov.cn/2014-11/25/content_2783092.htm .

18. Also see http://www.economist.com/news/international/21613334-vast-tree-planting-arid-regions-failing-halt-deserts-march-great-green-wall .

19. The National Peoples Congress announced in 2011 that it wanted to develop seven “new strategic industries” to foster Chinas transition from low-cost workshop of the world into producer of high-value, high-technology goods. The seven strategic industries are: alternative fuel cars, biotechnology, environmental and energy-saving technologies, alternative energy, advanced materials, new-generation information technology, and high-end equipment manufacturing.

20. One sign of Chinas unique capability in terms of educational transformation is the fact that in 2003, there were about 2 million university graduates in China, whereas 10 years later this number had increased to more than 7 million.

21. According to the Chinese governments estimate, by 2015 Chinas energy saving and environmental protection sector will be worth CN¥4.5 trillion (Ng and Mabey, 2011 ).

22. The reasons for this have been hotly debated. Some observers attribute Chinas attitude to a socialisation by the prevailing international norms, others more cynically see Chinas behaviour as a calculated attempt to reduce the security dilemma created by Chinas rise, so as to avoid other nations seeking to balance Chinas power. For whatever reason, China has become an integral stakeholder in the current international system. (Wang and Rosenau, 2009).

23. For an overview of such initiatives, see http://www.iea.org/publications/insights/insightpublications/MappingMultilateralCollaboration_FINAL.pdf .

24. Chinas economic growth model is highly trade-oriented; the value of Chinese exports reached an all-time high in 2013, at US$2.2 trillion or 27% of Chinas GDP.

25. For more information on the Sustainable Development Goals, http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300 .

26. In paragraph 31 (iii), http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/min01_e/mindecl_e.htm .

27. For the APEC, 2011 Leaders Statement on Environmental Goods and Services, http://www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Leaders-Declarations/2011/2011_aelm/2011_aelm_annexC.aspx .

28. The ITA model allows for negotiations among a limited group of countries and gives effect to the outcome by adjusting Members goods and services schedules. Consequently, MFN treatment is extended to all Members, meaning that even non-signatories to the agreement benefit from the concessions made by the parties to the agreement. As its subject matter is restricted to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the equivalent for services (GATS), the scope of an ITA type of agreement will be limited. Further, it may only yield rights and not diminish obligations of Members.

29. https://www.ustr.gov/sites/default/files/EGs-Announcement-joint-statement-012414-FINAL.pdf .

30. According to UNEP a green economy is an economy that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. In its simplest expression, a green economy is low carbon, resource efficient and socially inclusive.

31. Non-tariff barriers are five times more important than tariff barriers (de Melo and Vijil, 2014 ).

32. The market for sustainable energy services is at least as big as the market for the related goods, and trade in goods and services is highly complementary in the area of clean energy. However, the tariff-equivalent level of barriers to trade in professional services can be as high as 60% in some regions of the world. (Borchert et al., 2012 ).

33. According to the International Energy Agencys (IEA, 2014 ) energy efficiency has a major role to play GHG emission reductions. Energy efficiency policies are increasingly used to promote and accelerate the deployment of energy efficiency technologies, which include energy performance standards and energy labelling. These requirements, however, can form trade barriers if they differ by country and region and can hinder trade flows in energy efficient goods and technologies.

34. http://www.pv-tech.org/news/exports_of_us_solar_products_to_china_reach_913m_surplus_in_2011 .

35. http://www.wto.org/english/news_e/sppl_e/sppl83_e.htm .

36. Costa Rica for example did not have any ICT-related exports when it joined the ITA in 1996. By now, ICT related exports make up for a quarter of Costa Ricas total exports, so it is important to put the future of the clean tech sector in a dynamic perspective.

37. The WTOs Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement in its Article 2.4 promotes the expanded use of international standards, stating that: “Where technical regulations are required and relevant international standards exist or their completion is imminent, Members shall use them, or the relevant parts of them, as a basis for their technical regulations except when such international standards or relevant parts would be an ineffective or inappropriate means for the fulfilment of the legitimate objectives pursued, for instance because of fundamental climatic or geographical factors or fundamental technological problems.”

38. The World Trade Organization (WTO), which started its Aid for Trade initiative in 2005, provides the following definition: “Aid for Trade is about helping developing countries, in particular the least developed, to build the trade capacity and infrastructure they need to benefit from trade opening”. The WTO notes that “trade has the potential to be an engine for growth that lifts millions of people out of poverty”, but that “internal barriers — lack of knowledge, excessive red tape, inadequate financing, poor infrastructure” hamper that potential.

39. Authors note: In addressing climate mitigation efforts, it makes sense to reconsider meat consumption. Also see Bajželj et al. (2014) .

40. For more details on linking different ETSs, see ICTSD (2014) .

41. Beyond aviation, the EU is also interested in applying market-based measures to emissions from the shipping sector. The International Maritime Organization has until now taken measures related to energy efficiency and ship design for lowering emissions, but its Members could not agree on applying an MBM to the shipping sector.

42. For an assessment of the costs of the EU ETS,http://www.ictsd.org/downloads/2011/11/the-inclusion-of-aviation-in-the-eu-emissions-trading-system.pdf .

43. E.g. the US-Mexico Bilateral Framework on Clean Energy and Climate Change and the Australia-EU Partnership Framework.

44. Here the EUs effort to address illegal (tropical) timber trade by its Action Plan for Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) could serve as an example. FLEGT relies on voluntary participation, focusing on clear tenure rights for forest communities, more transparency and inclusion of all stakeholders in concession allocation, as well as training and awareness-raising for governmental and civil society actors. FLEGT is implemented through so-called Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs) that represent legally binding trade agreements between the EU and partner countries. FLEGT is supposed to prevent illegal timber exports into the EU while enlarging the share of legal timber imported and fostering the demand for timber from sustainably managed sources.

45. Decision -/CP.20 ('Lima call for climate action', available at https://unfccc.int/files/meetings/lima_dec_2014/application/pdf/auv_cop20_lima_call_for_climate_action.pdf .

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?