Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The potential of technology in digital society offers multiple possibilities for learning. E-books constitute one of the technologies to which great attention has to be paid. This article presents a case study on the perceptions held by a teacher and his students on the use of e-textbooks in a Primary education classroom. It examines students’ meaning-making practices and the perceptions that teachers and students have towards their engagement in learning activities in this context. In the analysis of the data generated, the classroom is considered a multimodal learning space, where virtual, physical and cognitive environments overlap, allowing students to negotiate meaning across multiple contexts and reflect upon it. Results show that e-textbook users’ perceptions greatly depend on the institutional culture in which they are embedded. While the adoption of e-textbooks does not necessarily mean a transition from traditional textbooks to e-textbooks, students and teachers may develop a more demanding range of criteria which must be met by e-textbook providers. By doing this, e-books become a real alternative to free internet resources. Although e-textbooks favor a communicatively active style of learning, there are still real challenges to be overcome by publishers so that e-textbooks do not become the next forgotten fad.

1. Introduction

Today’s pedagogical practices are largely permeated by the tools and semiotic resources of the digital age, a period which has lately undergone changes metaphorically described as coming from the solid culture of the 19th and 20th centuries to the liquid information culture of the 21st century (Area & Pessoa, 2012). E-books and e-textbooks may be described as examples of such tools, which offer new opportunities as well as challenges for teachers and learners in a continuously evolving educational landscape. In general, good information on book sales is hard to come by since industry interests influence most figures. However, in order to capture the size and scope of the subject, the US market can be taken as an example, where the consistent growth of e-books demonstrates that publishers have successfully evolved the technology environment for their content. According to the 2013 report presented by BookStats, e-books are now fully embedded in the format infrastructure of trade book publishing (BookStats, 2013). In fact, e-books sales have grown 45% since 2011, comprising 20% of the current trade market and playing an integral role in 2012 trade revenue.

This present research paper examines the perceptions that one teacher and his students have towards e-textbooks in an elementary school. Most research conducted on e-textbooks to date has been on undergraduates (Sun, Flores & Tanguma, 2012; Quan-Haase & Martin, 2011; Rose, 2011; Nicholas, Rowlands & Jamali, 2010), who can be expected to have far more sophisticated study techniques and work practices than students who are in elementary school. An increasing number of primary, middle and high schools are in the process of testing out the switch from printed textbooks to e-textbooks. The Educat 1x1 project, launched by the Education Department of Catalonia, Spain, in 2010, is one such initiative (Veguin, 2010). It aims at the progressive introduction of one computer per student, digital books, and other computerized curriculum materials in the classrooms. In a pool aimed at identifying the perception of teachers participating in the project, Padrós-Rodríguez (2011) found that the majority of them do not see the 1x1 project as necessarily related to the adoption of e-textbooks.

In this paper it is discussed how e-textbook adoption raises questions that greatly depend on institutional culture. Attention focuses on the meaning-making practices of a classroom while performing learning activities. Specifically, classroom interaction and participants’ feedback and comments made on the experience are analyzed in depth. The objective is to gather data on teacher and students’ perception on e-textbook use in the context of an elementary school. Some of the guiding study questions of this present research have been: Do kids have favorable, negative or mixed perceptions on e-textbook use? Do kids and their teacher hold a shared perception on the use of e-textbooks? How does school culture regarding selection of course materials for students influence e-textbook adoption? In writing this paper, we hope to contribute to the understanding of how school culture and classroom idiosyncrasies may pose further considerations regarding whether e-textbooks should be adopted in the classroom.

2. Theoretical basis

The observed classroom is approached as a multimodal learning space, where virtual, physical and cognitive environments overlap. In the first part of the theoretical principals, modality is explored as a useful framework to develop our approach. It leads us to considering e-textbooks as semiotic resources, as will be discussed in the second part of our theoretical basis. In the third part, the relevance of studying student and teacher perceptions on the use of e-textbooks is presented and examined. This way the complexity of pedagogic practices in relation to traditional and new literacy technologies is taken into consideration.

2.1. A multimodal lens on digital technology, literacy and learning

Multimodal literacy emphasizes the fact that schools today do not respond to the multiplicity of texts with which students interact in real life (Kress, 2003; Jewitt, 2006; 2008). Researchers such as Unsworth, Thomas and Bush (2004), Unsworth (2006), Jewitt and Gunther (2003) state that the school continues to focus on the genres of written communication, whereas reality offers multiple modes of communication such as the visual, auditory and gestural.

Significant literature accounts for the technologization of school literacies and pedagogy (Cope & Kalantis 2000; Lankshear & Knobel, 2003; Marsh, 2005; Leander, 2007). Emerging literacies change the educational landscape (Lankshear & Knobel, 2003; Sefton-Green & Sinker, 2000). Teachers can integrate students’ knowledge of narrative characterization into the planning and creation of narratives, either in print (Millard, 2005; Newfield & al., 2003) or multimedia narratives (Burn & Parker, 2003; Marsh, 2006). Multimodal research reflects on the pedagogical use of semiotic resources. This constitutes the point of departure for our study as we understand the transition to e-textbooks is intended to respond to the communicative and technological requirements of a digitalized society. In the following section, we briefly present the definition of the e-textbook used in the present study, taking it as a semiotic resource.

2.2. Pedagogical affordances of digital textbooks

New technologies offer a varied potential for learning. We might expect people’s use of representational and communicative modes of new technologies to re-shape the social interaction experience of the classroom in complex ways. Although both publishers and libraries are unsure about the future and the impact of e-books, there is an increasing awareness that e-books demand further attention. As practitioners and researchers embark on a more extensive engagement with e-books, it has progressively become clear that there is major ongoing confusion on the definition of e-books (Lynch, 2001; Tedd, 2005; Edwards & Lonsdale, 2002). We will adhere to Vassiliou and Rowley (2008)’s e-book definition, which will allow us to move further into its pedagogical articulation. Vassiliou and Rowley (2008) define e-books as digital objects with textual and/or other content –semiotic resources, in a multimodal approach–, which arise as a result of integrating the familiar concept of a book with features that can be provided in an electronic environment. The authors claim e-books typically have in-use features such as search and cross reference functions, hypertext links, bookmarks, annotations, highlights, multimedia objects and interactive tools.

2.3. Teacher and students’ perceptions on e-textbook use

Dillon (2001a, 2001b) mentioned that school administrators might be interested in e-textbooks because they are relatively cheap, easy to handle, and capable of obtaining usage statistics. Even researchers skeptical of the replacement of analogue to digital reading technologies in schools acknowledge that ‘printed textbooks are heavy, quickly outdated, expensive to produce and purchase, and less exciting than the sexy digital content available via devices such as the iPad’ (Thayer, 2011: 2). In fact, at least part of the interest on e-textbooks is justified in terms of the need to identify ways to decrease the cost of college textbooks and supplemental resources, while still supporting academic freedom of faculty members to select high quality course materials for students (Reeves & Sampson, 2013).

Most research conducted on e-textbooks to date was aimed at undergraduates (Brint & Hier, 2005; Sun, Flores & Tanguma, 2012; Quan-Haase & Martin, 2011; Ditmyer & al., 201; Rose, 2011; Nicholas, Rowlands & Jamali, 2010) who naturally have far more sophisticated study techniques and work practices than elementary school students. E-texts receive mixed reviews from undergraduate students (Doering, Pereira & Kuechler, 2012; Jung-Yu & Khire, 2012; Lai & Ulhas, 2012; Rockinson- Szapkiw & al. 2013). Do students in elementary schools present as a varied perception on e-textbooks? Comparatively speaking, few studies have turned to schools for the time being and little is yet known about kids’ preferences in this subject area. Shiratuddin and Landoni (2002, 2003) found that kindergarten children are very much at ease with e-book technology, being able to use devices, e-books, and e-book builder without much effort. Obviously enough, their school level allows no inference on whether they would rather use traditional or e-texbooks. More recently, Shamir and Lifshitz (2013) examined the effect of activity with an educational electronic book (e-book), with/without metacognitive guidance, on the emergent literacy (rhyming) and emergent math (essence of addition, ordinal numbers) again of kindergartners, this time at risk for learning disability (LD). The researchers concluded that there was a significant improvement in the study variables among the two groups of subjects who worked with the e-book when compared to the control group, the experimental group that received metacognitive guidance as part of their e-book experience exhibiting greatest improvement in rhyming.

Thayer (2011) suggests elementary school students would benefit more from the replacement of printed textbooks with e-readers and slate computers, since young people typically have more malleable study habits and academic reading practices than undergraduate students. Though not specifically approaching e-books or e-textbooks, Burke and Rowsell (2008) developed a case study over digital reading practices of young adolescents. It highlighted the complexity of the critical skills young adolescents need to comprehend interactive texts. In the next section, we describe our study on the perception of students and teachers in an elementary school in Spain on e-textbook use.

3. Study method

The study questions which guided our reflections were: 1) Do kids have favorable, negative or mixed perceptions on e-textbook use?; 2) Do kids and their teacher hold a shared perception on the use o e-textbooks?; 3) How does school culture regarding selection of course materials for students influence e-textbook adoption? A case study approach (Yin, 1994, Yuen, Law & Wong, 2003; Hoseth & McLure, 2012) guided by multimodal principles (Jewitt, 2006; Knight, 2011) was adopted.

3.1. Data gathering

Three sources of data were used: 1) Video recording and class observational notes. In-depth focus group interviews, 2) E-textbook online platform. The data language is Catalan, the official language spoken in Catalonia, Spain. Whenever data transcripts are relevant to support analysis presentation, an English version of them will be provided.

3.2. Sampling

The school chosen for the study is a public primary school which does not use traditional textbooks. 14 students were involved in this study, 11 and 12 year olds. They are all Catalan speakers. All students in the observed group had computers at home and all, but one, had Internet connection. In class, each student had a laptop with access to internet and user name and password to access the e-textbook online platform. The teacher in charge of the group has been in this school for five years and has been the school technology planning coordinator for three years. He is 29 years old and uses technology in his classrooms on a regular basis to teach mathematics, social sciences and language.

3.3. Data gathering3.3.1. Lessons observation

The recordings lasted around 40 minutes each and took place in the participants’ usual classroom, a bright aired room which was a familiar setting for them. The classes seem to have had three distinct moments, however, there is no abrupt end and beginning of a new phase: 1) First, students began getting in the classroom, settling down, turning computers on and connecting to internet. The teacher gave brief instructions on the activity that the students were supposed to do and organized group sittings of students who had chosen to study the same period of history together. He also helped some students access the digital pedagogical materials on the server’s online platform. Altogether, this phase lasted about 10 minutes, though, occasionally, one or more students experienced more connections problems than the rest of the class. 2) In the second phase, students would concentrate in reviewing the information available in the e-textbook and in doing the activities the teacher had assigned them on the online platform. This phase lasted about 15 minutes. 3) In the last part of the classes, students would start to do the self correction of their activities. Most of them share their assessment grade with other students and/or the teacher and some of them ask the teacher why they were corrected in a particular way by the e-textbook. For most of the students, the teacher revises the digital textbook correction looking at their own laptops, but a few of the students would occasionally get their correction on the class digital board. This final part of the classes lasted about 15-18 minutes.

3.3.2. Focus group interviews

The focus group interviews were conducted at two different levels: student level and teacher level. The teacher interview lasted 25 minutes. Students were interviewed in groups with 3 or 4 participants. These interviews lasted approximately 10 minutes. All interviews were semi-structured. With consent from the respondents, all the discussions and interviews were video recorded.

3.3.3. The e-textbook

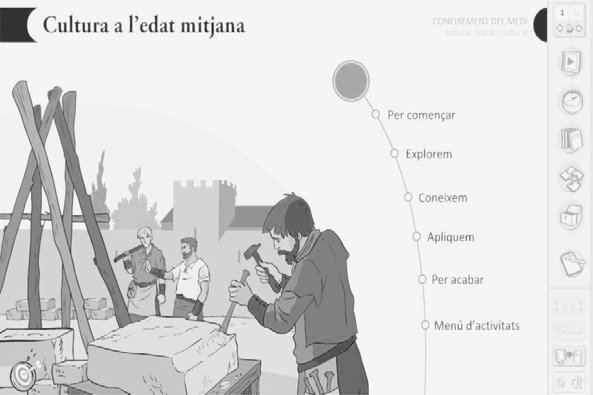

The e-textbook under analysis is available to students on an online educational platform managed by an e-learning content service provider. Each lesson was structured in six parts which can be accessed by a curved verbal side bar menu or from an iconic lateral menu, as can be seen in figure 1. The lessons are organized as follows:

• Get down to work: Students can find introductory text, images and activities.

• Let’s explore: Generally relates the content under study in the lesson to the students’ previous knowledge through self-correcting activities like quizzes, drag and drops, cross words, ordering letters or open questions.

• Let’s learn: Content is presented through a combination of text, images and animations.

• Applying knowledge: Students are expected to form groups and do activities that may involve interaction with their classmates and teacher, less dependent on technology.

• Wrapping it up: Students can find a list of the things they have learned in the lesson.

• Activity menu: Students have access to all the activities which are presented in the different parts of the lesson.

There are no videos in the materials selected by the teacher for the classes observed, neither links to Internet sources of related content. In the lateral side bar menu students could also find a link to a printable version of the unit, in PDF format.

The class recordings and field notes were reviewed and discussed by the authors. This information allowed us to prepare the semi-structured approach of the focus group interviews. At the data analysis phase, the interviews were inductively open coded for emergent themes and analyzed for patterns using grounded theory approach.

4. Analysis and results

Four main themes emerged out of the analysis of the interviews:

• Classroom roles: From the initial 5 minutes, when the teacher would tell the students what activity each group should do, there was no moment when all students were listening to the teacher. Students usually reviewed the content they had assigned to their group and did the corresponding activities. Those who had doubts on the corrections they received from the e-textbook raised their hands or called out the teacher’s name – something that happened pretty often. Students also extensively spoke to their classmates, especially in the self correction phase and after it, making comments on their punctuation, boasting, expressing surprise or complaining about it. The teacher frequently used the digital board to review the answers given by some students and at this moment some other students would listen to what was being said about their colleague’s activity correction.

• Mutual support: Though the teacher instructs the students to do the activity individually, this recommendation is taken in very flexible terms both by the students and by the teacher. When performing the activity, students would frequently check what was on their classmate’s screen, point at it, ask and answer questions. It was usually only after not being able to solve a difficulty by asking nearby colleagues that students would raise their hands and ask for the teacher’s help. The unsolved doubt of a student would become a shared doubt of many students as a consequence of presenting a challenge that none of the students seated near each other could solve. Such doubts could be technical aspects - especially if in the first phase of the class-, related to content, to the activities procedure or feedback, or more generally to the functioning of the e-textbook.

• Complementary literacy technologies: We identified the coexistence of traditional and digital literacy technologies in the pedagogical practice of the teacher in charge of the observed group. For example, apart from drawing on digital resources like the e-textbook lessons the group was using to study different periods of history, the students also created a timeline where they identified historical periods, outstanding historical characters and relevant facts for each period. The timeline was placed on the classroom walls.

It is not surprising that teachers draw on traditional and digital resources in different moments to achieve their pedagogical objectives. However, in the observed classes, the teacher drew on both traditional and digital technologies simultaneously. At the beginning of class, the teacher would give the students printed versions of the lessons they were supposed to study. This means all students received a printed document of the PDF which was available to students online as an option in the e-textbook menu. The teacher had three reasons for doing that: 1) He felt it was important to have an alternative in case the computers did not work properly or Internet was too slow; 2) He thought the printed documents would be useful for the kids at home; 3) He wanted to avoid students from getting lost, in case menu navigation was not enough to help them.

Most students drew on the printed versions of the lessons extensively, checking the computer screen and the paper documents in turns, as can be seen in figure 2. We asked the students if they thought the paper versions of the lessons were necessary. All students but one agreed they would not need them. However, class recordings show students looked for information as much on the printed documents as on the computer screen. In the focus group interviews, students explained they used the printed documents as a personal note taking resource. It seems reading on the screen was an easier step to accomplish than writing down the information they personally considered most important.

• A shared view, different perceptions: When we asked the study participants how well they valued the e-textbooks, we found that the students and the teacher both shared a common view on it, but different perceptions regarding this view. The common view is that both the teacher and the students think the e-textbook used in their history project classes presents very specific, concrete information. This shared view of the digital resource, however, leads to different perceptions on it. While the students liked the resource style, highlighting the easiness to find the information they wanted to do the activities proposed, the teacher valued it negatively because it offered students a limited amount of information.

All students said they liked the e-textbook and they actually preferred using it to traditional textbooks. However, they also seemed to find the information presented in the material insufficient, since one recurrent theme in the focus group interviews was the possibility to complete the information using search engines, like Google, or complementary sources of content, like Wikipedia. The students actually did not seem to draw a definite line distinguishing the e-textbook from other digital resources.

Easiness to do activities and find information, the possibility to see images and videos, and the novelty of e-textbooks were the positive aspects of e-textbooks highlighted by the students. The teacher, on the other hand, was less attracted then students by e-textbooks. The teacher also had a list of other limitations which will probably hinder future e-textbook adoption in the case school. First, the teacher acknowledged this generation of e-textbooks is better than previous materials, which were simply PDFs, but he still missed more multimodal content. Secondly, the perspective given in the materials is frequently farfetched from a more local view of relevant facts.

Thirdly, the teacher thought the economic limitation would be an important obstacle for the adoption of the e-textbook at the case school. The school would have to pay to use the platform and also pay for the educational resources. In the case school, teachers were supposed to develop the curriculum drawing extensively on their own ability to find and elaborate pedagogical materials. In this situation, e-textbooks would have to offer a richness of form and content which does not convince the teacher we interviewed for the moment: «You can find it all on the Internet, and here (e-textbooks) you have to pay. You have to pay for the platform and for the educational resources. If you have it well structured, you can find it all on the net» (Teacher).

Notwithstanding the more than reluctant perception the teacher expressed on e-textbooks, we could notice the students clearly enjoyed using it. We asked the teacher if the students simply enjoyed anything or if he thought there was something special about this material that was calling their attention: «These students are happy to come to school. They want to learn, they like anything that is new to them. I think some time in the future, after they grow up like this, using so much technology, you will give them a sheet of paper and they will «uaaauu», a sheet of paper. That’s so cool» (Teacher). In this respect, the teacher’s perception is that the reason the e-textbook is a success among students is in their own predisposition to learn, on the one hand, and on the resource’s novelty, on the other one.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The use of e-textbooks in the case classroom favored a sort of distributed learning. The teacher was definitely not the protagonist. Students’ work was something intermediate between being individual and collaborative. Additionally, the classroom was both a rich and supportive environment. Not being the centre of attention of the classroom gave the teacher enough freedom of movement to assist those students who requested his presence. There was also plenty of peer to peer support. Combined, those two results seem to indicate positive aspects of e-textbook use, even if they are not specific of this semiotic resource. It is obvious any digital learning object can produce such results, but the fact that an e-textbook does it is something notorious in itself. It shows that even if e-textbooks are not as multimodal as they could be, including videos and sound in the content presentation, they also do not seem to favor traditional teacher centered approaches in which the teacher is the main source of feedback in the classroom.

Literacy technologies change fast, pedagogical practices do not. The case classroom observations showed there was a symbiotic interaction of digital and non digital technologies. The pictures and drawings which changed the classroom wall into a timeline, for example, constitute semiotic work which compliments in symbiotic ways the work done while students engaged with the e-textbooks. Also, while students were using the e-textbook itself, they often referred to the printed version of the lesson provided by their teacher. It is possible they did not need the printed materials, but the class observation clearly shows students extensively use them as scaffolds. There is no simple way to take all the richness of symbolic meaning going on during a classroom into account. Multimodal theory is clearly an attempt to, from the acknowledgement of the diversity of data available to the analyst, makes an effort to systematize impressions not always easy to reconcile. If the analyst only takes into account clear cut realities presented in objective data, much of the meaning making practices going on during the most ordinary classroom will simply be disregarded, though the richness of the evidence.

We asked at the beginning of this paper if kids have favorable, negative or mixed perceptions on e-textbook use, if the kids and their teacher hold a shared perception on the use of e-textbooks and how school culture regarding selection of course materials for students influence e-textbook adoption. Kids participating in this research hold favorable perceptions on e-textbooks. The students enjoyed using the e-textbook and reported preferring it to traditional textbooks, however expressing the need to compliment its information using search engines, like Google, or complementary sources of content, like Wikipedia. The students are not always able to distinguish the e-textbook from other digital resources: the computer (in the case of this present research), the Ipad or the e-book reader seems to be what kids identify as the learning object, not the semiotic resources which educators make available to them on the different pieces of technology they use.

As mentioned above, the students and the teacher basically shared a common view on the e-textbook, but different perceptions regarding the specific e-textbook used. The common view is that the e-textbook used in their history project classes presents very specific, concrete information. The differing perception is that while the students liked the resource style, highlighting the easiness to find the information they wanted to do the activities proposed, the teacher valued it negatively because it offered students a limited amount of information. Finally, it could be said that e-textbook users’ perceptions greatly depend on the institutional culture in which they are embedded. In contexts like the case school, where the adoption of e-textbooks does not mean a transition from traditional textbooks to e-textbooks, students and teachers may develop a more demanding range of criteria which will have to be met by e-textbook providers so as they can become a real alternative to all the resources teachers can find for free on the Internet. The results of this study indicate that although e-textbooks favor a communicative active style of learning and are attractive to elementary school students, there still are real challenges to be overcome by editorials so that e-textbooks do not become the next forgotten fad.

6. Limitations and Ethical considerations

The purpose of this research is not to make any generalized claims on e-textbook use or perception. Thus, the relevance of our case study should be understood as illustrative rather than definitive. More research will be needed to shed light on the wider scope of this intellectual endeavor. Permission must be requested for the video recordings to be shown with the research team, allowing short clips, stills and photos to be used for teaching and dissemination purposes.

References

Area, M. & Pessoa, T. (2012). From Solid to Liquid: New Literacies to the Cultural Challenges of Web 2.0. Comunicar, 38, 13-20. (DOI: 10.3916/C38-2011-02-01).

Armstrong, C., Edwards, L. & Lonsdale, R. (2002). Virtually There? E-books in UK Academic Libraries. Program: Electronic Library and Information Systems, 36, 216-227. (DOI: 10.1108/00330330210447181).

Bookstats (Ed.) (2013). Bookstats 2013 Now Available [Press release]. (www.bookstats.org/pdf/BookStats-Press-Release-2013-highlights.pdf). (20-05-2013)

Burke, A. & Rowsell, J. (2008). Screen Pedagogy: Challenging Perceptions of Digital Reading Practice, Changing English. Studies in Culture and Education, 15(4), 445-456. (DOI: 10.1080/13586840802493092).

Burn, A. & Parker, D. (2003). Tiger’s Big Plan: Multimodality and Moving Image. In C. Jewitt & G. Kress (Eds.), Multimodal literacy, 56-72. New York: Peter Lang.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (Eds). (2000). Multiliteracies. London: Routledge.

Dillon, D. (2001a). E-books: the University of Texas Experience, part 1. Library Hi Tech, 19(2), 113-125.

Dillon, D. (2001b). E-books: the University of Texas Experience, part 2. Library Hi Tech, 19(4), 350-362.

Ditmyer, M.M., Dye, J. & al. (2012). Electronic vs. Traditional Textbook Use: Dental Students’ Perceptions and Study Habits. Journal of Dental Education, 76, 6, 728-738.

Doering, T., Pereira, L. & Kuechler, L. (2012). The Use of E-Textbooks in Higher Education: A Case Study. Berlin (Germany): E-Leader.

Jewitt, C. & Gunther, K. (Eds). (2003). Multimodal Literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, Literacy, Learning: A Multimodality Approach. London: Routledge.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and Literacy in School Classrooms. Review of Research in Education, 32, 241-267. (DOI: 10.3102/0091732X07310586).

Knight, D. (2011). Multimodality and Active Listenership: a Corpus Approach. New York: Continuum.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge.

Lai, J.Y. & Ulhas, K.R. (2012). Understanding Acceptance of Dedicated E-textbook Applications for Learning: Involving Taiwanese University Students. The Electronic Library, 30, 3, 321-338. (DOI: 10.1108/02640471211241618).

Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2003). New Literacies: Changing Knowledge and Classroom Learning. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Leander, K. (2007). Youth Internet Practices and Pleasure: Media Effects Missed by the Discourses of «Reading» and «Design». Keynote Delivered at ESRC Seminar Series: Final Conference. London: Institute of Education.

Lynch, C. (2001). The Battle to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World. First Monday, 6 (6). (http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/864/773) (14-02-2013).

Marsh, J. (2006). Global, Local/Public, Private: Young Children’s Engagement in Digital Literacy Practices in the Home. In K. Pahl & J. Rowsell (Eds.), Travel notes From the New Literacy Studies: Instances of Practice, (pp.19-38). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Marsh, J. (Ed). (2005). Popular Culture, New Media and Digital Literacy in Early Childhood. London: Routledge/Falmer.

Millard, E. (2005). To Enter the Castle of Fear: Engendering Children’s Story Writing from Home to School at KS2. Gender and Education, 17(1), 57-63. (DOI: 10.1080/0954025042000301302).

Newfield, D., Andrew, D., Stein, P. & Maungedzo, R. (2003). No Number Can Describe How Good it Was: Assessment Issues in the Multimodal Classroom. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice 10, 1, 61-81. (DOI: 10.1080/09695940301695).

Nicholas, D; Rowlands, I. & Jamali, H.R. (2010). E-textbook Use, Information Seeking Behavior and its Impact: Case Study Business and Management. Journal of Information Science, 36(2), 263-280. (DOI: 10.1177/0165551510363660).

Padrós-Rodríguez, J. (2011). El Projecte EduCAT1x1. ¿Què pensen els implicats. Espiral, Educación y Tecnología. (http://ciberespiral.org/informe_espiral1x1.pdf) (20-02-2013).

Quan-Haase, A. & Martin, K. (2011). Seeking Knowledge: An Exploratory Study of the Role of Social Networks in the Adoption of Ebooks by Historians. Proceedings of the American Society for Informa-tion Science and Technology, 48, 1-10.

Reeves, D. & Sampson, C. (2013). E-Textbooks and Students: Shifting Perceptions. Paper Presented at Library Technology Conference. Minessota, USA.

Rockinson-Szapkiw, A.J., Courduff, J., Carter, K. & Bennett, D. (2013). Electronic Versus Traditional Print Textbooks: A Comparison Study on the Influence of University Students' Learning. Computers & Education, 63, 259-266. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.022).

Rose, E. (2011). The Phenomenology of On-screen Reading: University Students' Lived Experience of Digitised Text. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42, 515–526. (DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01043.x).

Sefton-Green, J. & Sinker, R. (Ed). (2000). Evaluating Creativity: Making and Learning by Young People. London: Routledge.

Shamir, A. & Lifshitz, I. (2013). E-Books for Supporting the Emergent Literacy and Emergent Math of Children at Risk for Learning Disabilities: can Metacognitive Guidance Make a Difference? European Journal of Special Needs, 28, 1, 33-48. (DOI: 10.1080/08856257.2012.742746).

Shiratuddin, N. & Landoni, M. (2002). E-Books, E-publishers and E-book Builders for Children. New Review of Children's Literature Librarianship, 8, 1, 71-88. (DOI: 10.1080/13614540209510660).

Shiratuddin, N. & Landoni, M. (2003). Children’s E-Book Technology: Devices, Books, and Book Builder. Information Technology in Childhood Education Annual, 1, 105-138. AACE. (www.editlib.org/p/18870) (19-08-2013).

Sun, J., Flores, J. & Tanguma, J. (2012). E-textbooks and Students’ Learning Experiences. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 10, 63-77. (DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4609.2011.00329.x).

Tedd, L.A. (2005). E-books in Academic Libraries: An International Overview. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 11(1), 57-79.

Thayer, A. (2011). The Myth o Paperless School: Replacing Printed Texts with E-readers. Proceedings of the Child Computer Interaction (pp. 18-21).Canada: Vancouver, BC.

Unsworth, L., Thomas, A. & Bush, R. (2004). The Role of Images and Image-text Relations in Group ‘Basic Skills Tests’ of Literacy for Children in the Primary Years. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 27(1), 46-65.

Unworth, L. (2006). Towards a Metalanguage for Multiliteracies Education: Describing the Meaning-Making Resources of Language-Image Interaction. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 5(1), 55-76.

Vassiliou, M. & Rowley, J. (2008). Progressing the Definition of «E-book», Library Hi Tech 26(3), 355-368. (DOI: 10.1108/07378830810903292).

Veguin, J.G. (2010). [Letter]. (www.edubcn.cat/rcs_gene/extra/00_educat_1x1/01_cartes/carta_centre_concertats_novembre10v2.pdf) (14-02-2013).

Yin, R.K. (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Yuen, A.H.K., Law, N. & Wong, K.C. (2003). ICT Implementation and School Leadership: Case Studies of ICT Integration in Teaching and Learning. Journal of Educational Administration. 41, 158-170. (DOI: 10.1108/09578230310464666).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El potencial que posee la tecnología en el marco de una sociedad digitalizada supone también múltiples oportunidades para el aprendizaje. Los libros electrónicos constituyen una de esas tecnologías a las que hay que prestar especial atención. En este artículo se presenta un estudio de caso sobre la percepción de un profesor y sus estudiantes sobre el uso de un libro de texto electrónico en un aula de Educación Primaria. Se examinan prácticas de construcción de significado y actitudes mientras se realizan actividades con un libro de texto electrónico. El aula se considera como un espacio de aprendizaje multimodal en el que se solapan entornos como el virtual, el físico y el cognitivo. Los estudiantes negocian significados en múltiples contextos, reflexionando durante el proceso. Los resultados demuestran que la percepción de los usuarios de los libros de texto electrónicos depende de la cultura institucional en la que están inmersos. Cuando su adopción no significa una transición de los libros de texto tradicionales a los libros de texto electrónicos, existe una gama más exigente de criterios a fin de que puedan convertirse en una alternativa real a los recursos disponibles en Internet. Pese a que los libros de texto electrónicos favorecen un estilo activo y comunicativo de aprendizaje, aún existen desafíos reales que las editoriales deben superar para que el libro de texto electrónico no se convierta en una moda pasajera.

1. Introducción

Las prácticas pedagógicas actuales hacen un gran uso de las herramientas y los recursos semióticos de la era digital, período que últimamente ha sufrido cambios metafóricamente descritos como provenientes de la cultura sólida de los siglos XIX y XX hacia la cultura líquida de la información del siglo XXI (Area & Pessoa, 2012). Los libros electrónicos y los libros de texto electrónicos podrían describirse como ejemplos de dichas herramientas. Para capturar el tamaño y alcance del asunto, podemos tomar el mercado estadounidense como ejemplo. De acuerdo con el informe de 2013 presentado por BookStats, los libros electrónicos ya están totalmente integrados en la infraestructura de formatos de la publicación de libros comerciales (Bookstats, 2013). Los libros electrónicos crecieron un 45% desde 2011 y ahora constituyen el 20% del mercado, jugando un papel fundamental en los ingresos del sector de 2012; el género más vendido fue la ficción para adultos.

La presente investigación examina las percepciones que un profesor y sus estudiantes tienen sobre los libros de texto electrónicos en un centro de Educación Primaria. La mayoría de las investigaciones realizadas hasta la fecha sobre los libros de texto electrónicos se centraban en estudiantes universitarios (Sun, Flores & Tanguma, 2012; Quan-Haase & Martin, 2011; Rose, 2011; Nicholas, Rowlands & Jamali, 2010). Un número creciente de centros de Primaria, secundaria y superior se encuentra en el proceso de probar el cambio de los libros de texto impresos a los libros de texto electrónicos. Una de estas iniciativas es el proyecto Educat 1x1, lanzado por el Departamento de Educación de Cataluña (España) en el 2010 (Veguin, 2010). Su objetivo es introducir progresivamente en las aulas un ordenador por alumno, libros digitales y otro material escolar informatizado. En un equipo formado para identificar la percepción del profesorado participante en el proyecto, Padrós-Rodríguez (2011) destacó que la mayoría de los integrantes no veía el proyecto 1x1 como algo necesariamente relacionado con la adopción de los libros de texto electrónicos.

En este artículo se habla del modo en que la adopción del libro de texto electrónico pone de manifiesto cuestiones que dependen en gran medida de la cultura institucional. En particular, se analiza la interacción de la clase y las respuestas y comentarios de los participantes sobre la experiencia. La finalidad es recabar datos sobre la percepción de estudiantes y profesor sobre el uso del libro de texto electrónico en Educación Primaria. Algunas de las preguntas motoras de esta investigación fueron: ¿El alumnado tiene una percepción positiva, negativa o mixta sobre el uso del libro de texto electrónico? ¿Comparten alumnos y profesor la misma percepción sobre el uso de libros de texto electrónicos? ¿Cómo influye la cultura del centro en materia de elección de materiales del curso para los estudiantes en la adopción del libro de texto electrónico? Al redactar este artículo esperamos ayudar a entender el modo en que la cultura de los centros y la idiosincrasia de las aulas puede revelar nuevos elementos que se deben tener en cuenta para decidir si adoptar o no los libros de texto electrónicos.

2. Base teórica

El aula observada se considera como un espacio de aprendizaje multimodal en el que se solapan entornos como el virtual, el físico y el cognitivo. En la primera parte de los principios teóricos, la modalidad se explora como un marco útil para desarrollar nuestro enfoque. Ello nos lleva a considerar el libro de texto electrónico como un recurso semiótico, como se planteará en la segunda parte de nuestra base teórica. En la tercera parte, se presenta y examina la importancia del estudio de la percepción de estudiantes y profesor sobre el uso del libro de texto electrónico. Así, tenemos en cuenta la complejidad de las prácticas pedagógicas en relación con las tecnologías de alfabetización tradicionales y nuevas.

2.1. Una visión multimodal sobre la tecnología digital, la alfabetización y el aprendizaje

La alfabetización multimodal hace hincapié en el hecho de que los centros educativos actuales no responden a la mutiplicidad de textos con los que los estudiantes interactúan en la vida real (Kress, 2003; Jewitt, 2006; 2008). Investigaciones como las de Unsworth, Thomas y Bush (2004), Unworth (2006), Jewitt y Gunther (2003) ponen de manifiesto que los centros educativos siguen centrándose en los géneros de comunicación escrita, mientras que la realidad ofrece múltiples canales comunicativos como el visual, el auditivo o el gestual.

Hay bastante bibliografía relacionada con la tecnologización de la alfabetización escolar y la pedagogía (Cope & Kalantis 2000; Lankshear & Knobel, 2003; Marsh, 2005; Leander, 2007). Las alfabetizaciones emergentes cambian el entorno educacional (Lankshear & Knobel, 2003; Sefton-Green & Sinker, 2000). El profesorado puede integrar los conocimientos del alumnado en materia de caracterización narrativa en la planificación y creación narrativa, tanto impresa (Millard, 2005; Newfield & al., 2003) como multimedia (Burn & Parker, 2003; Marsh, 2006). La transición a los libros de texto electrónicos tiene por objeto responder a los requisitos comunicativos y tecnológicos de la sociedad digitalizada. En la sección siguiente se aborda brevemente la definición de libro de texto electrónico utilizada en este estudio, tomándolo como recurso semiótico.

2.2. Potencial pedagógico del libro de texto electrónico

Las nuevas tecnologías ofrecen diferentes posibilidades para el aprendizaje. Aunque tanto las editoriales como las bibliotecas no están seguras del futuro ni del impacto del libro electrónico, hay una conciencia cada vez mayor de que los libros electrónicos demandan más atención. Cada vez es más evidente que hay una gran confusión sobre la definición de libro electrónico (Lynch, 2001; Tedd, 2005; Armstrong, Edwards & Lonsdale, 2002). La definición de libro electrónico de Vassiliou y Rowley (2008) permite avanzar hacia su articulación pedagógica. Vassiliou y Rowley (2008) definen el libro electrónico como un objeto digital con contenido textual y/o diferente –fuentes semióticas, desde un enfoque multimodal–, que nace del resultado de integrar el concepto familiar de libro con características que se pueden proporcionar en un entorno electrónico. Los autores sugieren que los libros electrónicos suelen tener características integradas como la búsqueda y las referencias cruzadas, enlaces a hipertextos, marcas, anotaciones, subrayado, objetos multimedia y herramientas interactivas.

2.3. Percepciones de profesor y estudiantes sobre el uso del libro de texto electrónico

Dillon (2001a, 2001b) mencionó que las autoridades educativas podrían estar interesadas en los libros de texto electrónicos porque son relativamente baratos, fáciles de manejar, y capaces de mostrar estadísticas de uso. Incluso los investigadores más escépticos ante la sustitución de las tecnologías de lectura analógicas por las digitales en los centros educativos reconocen que «los libros de texto impresos son pesados, rápidamente obsoletos, caros de producir y comprar, y menos excitantes que el sexy contenido digital disponible a través de dispositivos como el iPad» (Thayer, 2011: 2). Al menos parte del interés de los libros de texto electrónicos se justifica en base a la necesidad de identificar vías de reducir el coste de los libros de texto académicos y recursos adicionales mientras se apoya la libertad académica de los miembros de la facultad para escoger materiales didácticos de gran calidad para los estudiantes (Reeves & Sampson, 2013).

Los libros electrónicos reciben revisiones mixtas por parte de los estudiantes universitarios (Doering, Pereira & Kuechler, 2012; Lai & Ulhas, 2012; Rockinson- Szapkiw & al., 2013). En términos comparativos, pocos estudios se han centrado en los centros de enseñanza primaria. Shiratuddin & Landoni (2002, 2003) descubrieron que los niños de los jardines de infancia se sienten muy cómodos con la tecnología de los libros electrónicos. Shamir y Lifshitz (2013) examinaron el efecto de la actividad con un libro electrónico educativo sobre los conocimientos emergentes (rimas) y las matemáticas emergentes (esencia de la suma, números ordinales) de nuevo en los jardines de infancia, en esta ocasión en riesgo por deficiencia de aprendizaje. Los investigadores llegaron a la conclusión de que había una mejora significativa en las variables de estudio entre los dos grupos de sujetos que trabajaron con los libros electrónicos, en comparación con el grupo de control.

Thayer (2011) sugiere que los estudiantes de Educación Primaria se beneficiarían más con la sustitución de los libros de texto impresos por lectores electrónicos y pantallas-pizarra, puesto que la juventud suele tener hábitos de estudio y prácticas de lectura académica más maleables que los estudiantes universitarios. Si bien no se centraban específicamente en los libros electrónicos o los libros de texto electrónicos, Burke y Rowsell (2008) desarrollaron un estudio de caso sobre las prácticas de lectura digital entre la adolescencia. Este destacaba la complejidad de las habilidades críticas necesarias para entender los textos interactivos. En la sección siguiente describiremos el estudio que hemos realizado para reunir datos sobre la percepción de estudiantes y profesores en un centro de enseñanza primaria de España sobre el uso del libro de texto electrónico.

3. Método de estudio

Las preguntas de estudio que guiaron nuestras reflexiones fueron las siguientes: 1) ¿El alumnado tiene una percepción positiva, negativa o mixta sobre el uso del libro de texto electrónico?; 2) ¿Comparten alumnos y profesor la misma percepción sobre el uso de libros de texto electrónicos?; 3) ¿Cómo influye la cultura del centro en materia de elección de los materiales del curso para los estudiantes en la adopción del libro de texto electrónico? Se adoptó un enfoque de estudio de caso (Yin, 1994, Yuen, Law & Wong, 2003) guiado por principios multimodales (Jewitt, 2006; Knight, 2011).

3.1 Recogida de datos

Se utilizaron tres fuentes de recopilación de datos: 1) Grabación de vídeo y notas de observación de la clase; 2) Entrevistas en profundidad con el grupo objeto de estudio, 3) Plataforma en línea del libro de texto electrónico. El idioma de los datos es el catalán. Siempre que sea preciso realizar transcripciones de los datos para apoyar la presentación del análisis, se proporcionará una versión en inglés de las mismas.

3.2. Muestras

El centro educativo escogido para el estudio es un colegio público de Educación Primaria que no utiliza libros de texto tradicionales. 14 estudiantes de entre 11 y 12 años participaron en este estudio. Todos ellos son hablantes del catalán. Todos los estudiantes del grupo observado tienen ordenadores en casa y todos menos uno tienen conexión a Internet. En el aula, cada estudiante tenía un portátil con acceso a Internet y un usuario y contraseña para acceder a la plataforma en línea del libro de texto electrónico. El profesor encargado del grupo lleva cinco años trabajando en este centro y también ha sido el coordinador de la planificación tecnológica del centro durante tres años. Tiene 29 años, y utiliza habitualmente la tecnología en sus clases para enseñar matemáticas, ciencias sociales y lengua.

3.3. Recogida de datos3.3.1. Observación de las clases

Las grabaciones tenían una duración aproximada de 40 minutos cada una y se realizaban en el aula habitual de los participantes. Las clases parecían tener tres momentos diferenciados, si bien no había un final abrupto ni un inicio entre cada fase nueva: 1) Primero los alumnos entraban en la clase, se sentaban, encendían los ordenadores y se conectaban a Internet. El profesor daba instrucciones breves sobre la actividad que se esperaba que hicieran los estudiantes y organizaba los grupos de estudio. También ayudaba a algunos estudiantes a acceder a los materiales pedagógicos digitales en la plataforma en línea del servidor. En conjunto, esta fase duraba unos 10 minutos, aunque a veces uno o más estudiantes tenían más problemas de conexión que el resto de la clase. 2) En la segunda fase, los alumnos se centrarían en revisar la información disponible en el libro de texto electrónico y en hacer las actividades que el profesor les había asignado en la plataforma en línea. Esta fase duraba unos 15 minutos. 3) En la tercera parte de las clases, los estudiantes empezarían a realizar la autocorrección de sus actividades. La mayoría de ellos compartían sus evaluaciones y puntuación con los otros estudiantes y/o con el profesor, y algunos le preguntaban al profesor por qué el libro de texto electrónico les hacía una determinada corrección. Para la mayoría de los alumnos, el profesor revisaba la corrección del libro de texto digital viendo sus propios portátiles, pero algunos estudiantes, ocasionalmente, obtenían su corrección de la pizarra digital de la clase. Esta última parte de la clase duraba entre 15-18 minutos.

3.3.2. Entrevistas con el grupo objeto del estudio

Las entrevistas con el grupo objeto se realizaron en dos niveles diferentes: nivel del alumno y nivel del profesor. La entrevista del profesor duró 25 minutos. Los estudiantes se entrevistaron en grupos de 3 o 4 participantes. Estas entrevistas tenían una duración aproximada de 10 minutos. Todas las entrevistas estaban semiestructuradas. Con el consentimiento de los entrevistados, todas las discusiones y entrevistas fueron grabadas en vídeo.

3.3.3. El libro de texto electrónico

El libro de texto electrónico en análisis está disponible para los alumnos en una plataforma didáctica en línea gestionada por un proveedor de contenidos de aprendizaje en línea. Cada lección se estructura en seis partes, como se puede ver en la figura 1. Las lecciones se organizan de la siguiente forma:

• Para empezar: textos introductorios, imágenes y actividades.

• Exploremos: mide los conocimientos previos del estudiante a través de actividades de autocorrección como tests, arrastrar y soltar, crucigramas, ordenar letras o preguntas abiertas.

• Aprendamos: una combinación de texto, imágenes y animaciones.

• Apliquemos los conocimientos: actividades que pueden implicar la interacción entre los alumnos y profesor, menos dependientes de la tecnología.

• Para acabar: lista de las cosas que han aprendido en la lección.

• Menú de actividades: se puede acceder a todas las actividades que se presentan en las diferentes partes de la lección.

No hay vídeos en los materiales escogidos por el profesor para las clases observadas, ni enlaces a fuentes de Internet de contenido relacionado. En la barra de menú de la parte lateral los alumnos también pueden encontrar un enlace a una versión imprimible de la unidad, en formato PDF.

Los registros de la clase y las notas de campo fueron revisados y debatidos por los autores. Esta información nos ha permitido preparar el enfoque semiestructurado de las entrevistas al grupo de estudio. Las entrevistas fueron descodificadas de un modo inductivo en temas emergentes, y analizadas por patrones según el enfoque de la teoría de base.

4. Análisis y resultados

Del análisis de las entrevistas se desprendieron cuatro temas principales:

• Papeles en clase: desde los primeros cinco minutos, en los que el profesor explicaba a los alumnos la actividad que debía realizar cada grupo, no hubo ningún otro momento en el que los estudiantes estuvieran escuchando al profesor. Los estudiantes solían revisar el contenido que habían asignado a su grupo y hacían las actividades correspondientes. Los que tenían dudas sobre las correcciones recibidas por parte del libro de texto electrónico levantaban la mano o llamaban al profesor por su nombre, algo que ocurría bastante a menudo. Los estudiantes también hablaban mucho con sus compañeros, especialmente en la fase de la autocorrección y después de esta, comentando sus puntuaciones, presumiendo, expresando sorpresa o quejándose. El profesor con frecuencia recurría a la pizarra digital para revisar las respuestas de algunos alumnos, y en ese momento otros alumnos escuchaban lo que se estaba diciendo sobre la corrección de las actividades de otros compañeros.

• Apoyo mutuo: aunque el profesor diga a los estudiantes que se supone que deben hacer la actividad individualmente, esta recomendación se toma con bastante flexibilidad por parte de los alumnos y del propio profesor. Al realizar la actividad, los estudiantes suelen comprobar lo que aparece en la pantalla de sus compañeros, señalarlo, preguntar y responder. Era frecuente que solo después de no haber podido resolver un problema preguntando a los compañeros más cercanos los estudiantes levantaran la mano para pedir ayuda al profesor. La duda no solucionada de un estudiante se convertiría en una duda compartida por los estudiantes próximos, como consecuencia de presentar un reto que ninguno de los compañeros cercanos podía resolver. Tales dudas podían ser cuestiones técnicas, especialmente en la primera fase de la clase, o relacionadas con el contenido, con el procedimiento de las actividades o respuesta, o, más generalmente, con el funcionamiento del libro de texto electrónico.

• Tecnologías de alfabetización complementarias: identificamos la coexistencia de tecnologías de alfabetización tradicionales y digitales en la práctica docente del profesor a cargo del grupo objeto de estudio. Además de echar mano de los recursos digitales, los estudiantes también dibujaron una línea del tiempo en la que identificaron los períodos históricos, destacando personajes históricos y hechos más destacados de cada período. La línea del tiempo se colocó en las paredes del aula.

En las clases observadas el profesor recurría tanto a tecnologías tradicionales como digitales simultáneamente. Al comienzo de la clase, el profesor daba a los alumnos versiones impresas de las lecciones que iban a estudiar. Todos los estudiantes recibían un documento impreso del PDF disponible en línea en el menú del libro de texto electrónico. El profesor tenía tres motivos para realizar esto: 1) Sentía que era importante tener una alternativa por si los ordenadores no funcionaban adecuadamente o la conexión a Internet era demasiado lenta; 2) Pensaba que los documentos impresos serían útiles para los estudiantes en casa; 3) No quería que los estudiantes se perdieran, en caso de que el menú de navegación no fuera suficiente para ayudarles.

La mayoría de los estudiantes recurría a las versiones impresas de las lecciones muy a menudo, comprobando la pantalla del ordenador y la documentación impresa por turnos, como se puede observar en la figura 2. Preguntamos a los estudiantes si pensaban que las versiones en papel de las lecciones eran necesarias. Todos los estudiantes excepto uno se mostraron de acuerdo en que no las necesitaban. Sin embargo, las grabaciones de las clases muestran cómo los estudiantes buscaban información tanto en los documentos impresos como en la pantalla del ordenador. En las entrevistas al grupo de estudio, los alumnos explicaron que utilizaban la documentación impresa como recurso para tomar notas personales.

• Una visión común, diferentes percepciones: cuando preguntamos a los participantes en el estudio cómo valoraban sus libros de texto electrónicos, comprobamos que los estudiantes y el profesor básicamente compartían un mismo punto de vista que, sin embargo, llevaba a la elaboración de diferentes percepciones. La visión común es la siguiente: tanto el profesor como el alumnado piensa que el libro de texto electrónico utilizado en sus clases de proyecto de historia presenta una información muy concreta y específica. Pero esta perspectiva común sobre la fuente digital lleva a diferentes percepciones sobre ella. Mientras que a los estudiantes les gustaba el estilo de la fuente, destacando la facilidad para encontrar la información que querían para hacer las actividades propuestas, el profesor la valoraba negativamente porque ofrecía a los estudiantes una cantidad limitada de información.

Todos los estudiantes afirmaron que les gustaba el libro de texto electrónico y, de hecho, preferían usar este a los libros de texto tradicionales. No obstante, también encontraban la información presentada en el material insuficiente, puesto que un tema recurrente en las entrevistas al grupo de estudio era la posibilidad de completar la información por medio de motores de búsqueda, como Google, o fuentes complementarias de contenido, como Wikipedia. En realidad, no parecía que los estudiantes trazaran una línea clara de diferenciación entre el libro de texto electrónico y otras fuentes de información digitales.

La facilidad para realizar actividades y encontrar información, la posibilidad de ver imágenes y vídeos, y la novedad de los libros de texto electrónicos eran los aspectos positivos que los alumnos destacaban de los libros de texto electrónicos. El profesor, por el contrario, se sentía menos atraído por el libro de texto electrónico que los alumnos. El profesor también tenía una lista de otras limitaciones que probablemente dificulten la adopción futura del libro de texto electrónico en el centro de estudio. En primer lugar, el profesor reconocía que esta generación de libros de texto electrónicos era mejor que el material previo, formado simplemente por PDFs, pero aún echaba en falta un contenido más multimodal. En segundo lugar, la perspectiva ofrecida en los materiales suele estar sacada de una visión más local de los hechos relevantes.

En tercer lugar, el profesor pensaba que la limitación económica sería un obstáculo importante para la adopción del libro de texto electrónico en su centro, que tendría que pagar para utilizar la plataforma y también para los recursos didácticos. En el centro objeto de estudio, los profesores desarrollan el plan de estudios recurriendo en gran medida a su propia capacidad para encontrar y elaborar materiales didácticos. En esta situación, los libros de texto electrónicos tendrían que ofrecer una riqueza de forma y contenido que, de momento, no convence al profesor que entrevistamos: «Puedes encontrarlo todo en Internet, y esto (libros de texto electrónicos) lo tienes que pagar. Tienes que pagar por la plataforma y por los recursos didácticos. Si lo tienes bien estructurado, puedes encontrarlo todo en la Red» (Profesor).

A pesar de la más que reacia percepción del profesor ante los libros de texto electrónicos, pudimos observar que los estudiantes disfrutaban bastante con su uso. Le preguntamos al profesor si los estudiantes simplemente disfrutaban con todo, o si pensaba que había algo especial en este material que les llamaba la atención: «Estos estudiantes están felices por venir al colegio. Quieren aprender, y les gusta todo lo que sea nuevo para ellos. Creo que dentro de algún tiempo, cuando ya hayan crecido así, utilizando tanta tecnología, les enseñaremos una hoja de papel y dirán « Uaaauu», una hoja de papel. Es genial» (Profesor). A este respecto, la percepción del profesor es que la razón por la que el libro de texto electrónico triunfa entre los estudiantes es inherente a su propia predisposición para aprender, por un lado, y a la novedad del recurso, por otro lado.

5. Debate y conclusión

El uso del libro de texto electrónico en el aula de referencia favorecía un tipo de aprendizaje distribuido. El profesor no era el protagonista. El trabajo de los alumnos estaba a medio camino entre el trabajo individual y el trabajo colaborativo. Había en el aula una atmósfera de gran apoyo. El profesor tenía la libertad de movimiento suficiente para ayudar a los estudiantes que requerían su presencia. También había una gran dosis de ayuda entre compañeros. En conjunto, estos dos resultados parecen reflejar aspectos positivos del uso del libro de texto electrónico, incluso si no son específicos de esta fuente semiótica. Es obvio que cualquier objeto digital de aprendizaje puede producir estos resultados, pero el hecho de que un libro de texto electrónico lo haga es destacable por sí mismo, porque significa que incluso si los libros de texto electrónicos no son todo lo multimodales que podrían ser, incluyendo vídeos y sonidos en la presentación del contenido, no parecen favorecer los enfoques tradicionales centrados en el profesor, en los que el profesor es la principal fuente de respuesta en la clase.

Las tecnologías de alfabetización cambian rápidamente, pero no las prácticas docentes. Las observaciones en el aula de referencia pusieron de manifiesto la interacción simbiótica entre las tecnologías digitales y no digitales. Las imágenes y dibujos que transformaron la pared de la clase en una línea del tiempo, por ejemplo, constituyen una muestra de trabajo semiótico que complementa de modo simbiótico el trabajo hecho mientras los estudiantes interactúan con los libros de texto electrónicos. Además, mientras los estudiantes utilizaban el libro de texto electrónico propiamente, solían recurrir a la versión impresa de la lección que el profesor les había proporcionado. La observación de la clase muestra claramente que los estudiantes utilizan en gran medida este material como apoyo.

Los alumnos que participaron en esta investigación tenían una perfección favorable sobre los libros de texto electrónicos. Los estudiantes disfrutaban utilizando el libro de texto electrónico y afirmaron que lo preferían al libro de texto tradicional, aunque expresaron la necesidad de completar su información con motores de búsqueda, como Google, o fuentes de contenido complementarias, como Wilkipedia. Los estudiantes no siempre son capaces de distinguir el libro de texto electrónico de otros recursos digitales: el ordenador (en el caso de esta investigación), el Ipad o el lector de libros de texto electrónicos parecían conformar lo que los estudiantes identificaban como el objeto de aprendizaje, no las fuentes semióticas que los educadores ponen a su disposición en los distintos elementos de tecnología que utilizan.

Como ya se ha dicho, los estudiantes y el profesor básicamente compartían la visión sobre los libros electrónicos, que llevaba a la elaboración de diferentes percepciones. La visión común era que el libro de texto electrónico utilizado en sus clases de proyecto de historia presenta una información muy concreta y específica. Pero esta perspectiva común sobre la fuente digital lleva a diferentes percepciones sobre ella. Mientras que a los estudiantes les gustaba el estilo de la fuente, destacando la facilidad para encontrar la información que querían para hacer las actividades propuestas, el profesor la valoraba negativamente porque ofrecía a los estudiantes una cantidad limitada de información. Por último, se podría decir que la percepción de los usuarios de los libros de texto electrónicos depende en gran medida de la cultura institucional en la que están inmersos. En contextos como el del centro educativo objeto del estudio, en donde la adopción de libros de texto electrónicos no significa una transición de los libros de texto tradicionales a los libros de texto electrónicos, estudiantes y profesores pueden desarrollar una gama más exigente de criterios que los proveedores de libros de texto electrónicos deben cumplir a fin de que puedan convertirse en una alternativa real a los recursos disponibles gratuitamente en Internet para los profesores. Los resultados de este estudio revelan que, pese a que los libros de texto electrónicos favorecen un estilo activo y comunicativo de aprendizaje y son atractivos para el alumnado de Primaria, aún existen desafíos reales que las editoriales deben superar para que el libro de texto electrónico no se convierta en una moda pasajera.

6. Limitaciones y consideraciones éticas

El propósito de esta investigación no es realizar afirmaciones generalizadas sobre el uso o la percepción del libro de texto electrónico. Así, la importancia de nuestro estudio de caso se debe entender como ilustrativa y no como definitiva. Es necesario pedir permiso para mostrar las grabaciones de vídeo dentro del equipo de investigación, para utilizar los cortometrajes, instantáneas y fotos con fines didácticos y de divulgación.

Referencias

Area, M. & Pessoa, T. (2012). From Solid to Liquid: New Literacies to the Cultural Challenges of Web 2.0. Comunicar, 38, 13-20. (DOI: 10.3916/C38-2011-02-01).

Armstrong, C., Edwards, L. & Lonsdale, R. (2002). Virtually There? E-books in UK Academic Libraries. Program: Electronic Library and Information Systems, 36, 216-227. (DOI: 10.1108/00330330210447181).

Bookstats (Ed.) (2013). Bookstats 2013 Now Available [Press release]. (www.bookstats.org/pdf/BookStats-Press-Release-2013-highlights.pdf). (20-05-2013)

Burke, A. & Rowsell, J. (2008). Screen Pedagogy: Challenging Perceptions of Digital Reading Practice, Changing English. Studies in Culture and Education, 15(4), 445-456. (DOI: 10.1080/13586840802493092).

Burn, A. & Parker, D. (2003). Tiger’s Big Plan: Multimodality and Moving Image. In C. Jewitt & G. Kress (Eds.), Multimodal literacy, 56-72. New York: Peter Lang.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (Eds). (2000). Multiliteracies. London: Routledge.

Dillon, D. (2001a). E-books: the University of Texas Experience, part 1. Library Hi Tech, 19(2), 113-125.

Dillon, D. (2001b). E-books: the University of Texas Experience, part 2. Library Hi Tech, 19(4), 350-362.

Ditmyer, M.M., Dye, J. & al. (2012). Electronic vs. Traditional Textbook Use: Dental Students’ Perceptions and Study Habits. Journal of Dental Education, 76, 6, 728-738.

Doering, T., Pereira, L. & Kuechler, L. (2012). The Use of E-Textbooks in Higher Education: A Case Study. Berlin (Germany): E-Leader.

Jewitt, C. & Gunther, K. (Eds). (2003). Multimodal Literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, Literacy, Learning: A Multimodality Approach. London: Routledge.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and Literacy in School Classrooms. Review of Research in Education, 32, 241-267. (DOI: 10.3102/0091732X07310586).

Knight, D. (2011). Multimodality and Active Listenership: a Corpus Approach. New York: Continuum.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge.

Lai, J.Y. & Ulhas, K.R. (2012). Understanding Acceptance of Dedicated E-textbook Applications for Learning: Involving Taiwanese University Students. The Electronic Library, 30, 3, 321-338. (DOI: 10.1108/02640471211241618).

Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2003). New Literacies: Changing Knowledge and Classroom Learning. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Leander, K. (2007). Youth Internet Practices and Pleasure: Media Effects Missed by the Discourses of «Reading» and «Design». Keynote Delivered at ESRC Seminar Series: Final Conference. London: Institute of Education.

Lynch, C. (2001). The Battle to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World. First Monday, 6 (6). (http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/864/773) (14-02-2013).

Marsh, J. (2006). Global, Local/Public, Private: Young Children’s Engagement in Digital Literacy Practices in the Home. In K. Pahl & J. Rowsell (Eds.), Travel notes From the New Literacy Studies: Instances of Practice, (pp.19-38). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Marsh, J. (Ed). (2005). Popular Culture, New Media and Digital Literacy in Early Childhood. London: Routledge/Falmer.

Millard, E. (2005). To Enter the Castle of Fear: Engendering Children’s Story Writing from Home to School at KS2. Gender and Education, 17(1), 57-63. (DOI: 10.1080/0954025042000301302).

Newfield, D., Andrew, D., Stein, P. & Maungedzo, R. (2003). No Number Can Describe How Good it Was: Assessment Issues in the Multimodal Classroom. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice 10, 1, 61-81. (DOI: 10.1080/09695940301695).

Nicholas, D; Rowlands, I. & Jamali, H.R. (2010). E-textbook Use, Information Seeking Behavior and its Impact: Case Study Business and Management. Journal of Information Science, 36(2), 263-280. (DOI: 10.1177/0165551510363660).

Padrós-Rodríguez, J. (2011). El Projecte EduCAT1x1. ¿Què pensen els implicats. Espiral, Educación y Tecnología. (http://ciberespiral.org/informe_espiral1x1.pdf) (20-02-2013).

Quan-Haase, A. & Martin, K. (2011). Seeking Knowledge: An Exploratory Study of the Role of Social Networks in the Adoption of Ebooks by Historians. Proceedings of the American Society for Informa-tion Science and Technology, 48, 1-10.

Reeves, D. & Sampson, C. (2013). E-Textbooks and Students: Shifting Perceptions. Paper Presented at Library Technology Conference. Minessota, USA.

Rockinson-Szapkiw, A.J., Courduff, J., Carter, K. & Bennett, D. (2013). Electronic Versus Traditional Print Textbooks: A Comparison Study on the Influence of University Students' Learning. Computers & Education, 63, 259-266. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.022).

Rose, E. (2011). The Phenomenology of On-screen Reading: University Students' Lived Experience of Digitised Text. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42, 515–526. (DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01043.x).

Sefton-Green, J. & Sinker, R. (Ed). (2000). Evaluating Creativity: Making and Learning by Young People. London: Routledge.

Shamir, A. & Lifshitz, I. (2013). E-Books for Supporting the Emergent Literacy and Emergent Math of Children at Risk for Learning Disabilities: can Metacognitive Guidance Make a Difference? European Journal of Special Needs, 28, 1, 33-48. (DOI: 10.1080/08856257.2012.742746).

Shiratuddin, N. & Landoni, M. (2002). E-Books, E-publishers and E-book Builders for Children. New Review of Children's Literature Librarianship, 8, 1, 71-88. (DOI: 10.1080/13614540209510660).

Shiratuddin, N. & Landoni, M. (2003). Children’s E-Book Technology: Devices, Books, and Book Builder. Information Technology in Childhood Education Annual, 1, 105-138. AACE. (www.editlib.org/p/18870) (19-08-2013).

Sun, J., Flores, J. & Tanguma, J. (2012). E-textbooks and Students’ Learning Experiences. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 10, 63-77. (DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4609.2011.00329.x).

Tedd, L.A. (2005). E-books in Academic Libraries: An International Overview. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 11(1), 57-79.

Thayer, A. (2011). The Myth o Paperless School: Replacing Printed Texts with E-readers. Proceedings of the Child Computer Interaction (pp. 18-21).Canada: Vancouver, BC.

Unsworth, L., Thomas, A. & Bush, R. (2004). The Role of Images and Image-text Relations in Group ‘Basic Skills Tests’ of Literacy for Children in the Primary Years. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 27(1), 46-65.

Unworth, L. (2006). Towards a Metalanguage for Multiliteracies Education: Describing the Meaning-Making Resources of Language-Image Interaction. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 5(1), 55-76.

Vassiliou, M. & Rowley, J. (2008). Progressing the Definition of «E-book», Library Hi Tech 26(3), 355-368. (DOI: 10.1108/07378830810903292).

Veguin, J.G. (2010). [Letter]. (www.edubcn.cat/rcs_gene/extra/00_educat_1x1/01_cartes/carta_centre_concertats_novembre10v2.pdf) (14-02-2013).

Yin, R.K. (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Yuen, A.H.K., Law, N. & Wong, K.C. (2003). ICT Implementation and School Leadership: Case Studies of ICT Integration in Teaching and Learning. Journal of Educational Administration. 41, 158-170. (DOI: 10.1108/09578230310464666).

Document information

Published on 31/12/13

Accepted on 31/12/13

Submitted on 31/12/13

Volume 22, Issue 1, 2014

DOI: 10.3916/C42-2014-08

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?