Abstract

Classical temples constructed by an entire class are considered as a democratic artifact that symbolizes social and communal beliefs and embodies religious significance. In contrast with these meanings that existing scholars have addressed, this paper investigates the extent to which architecture, as both shelter and artwork, serve as a medium of spatial–textile storytelling, providing a rich sensory context that represents and mediates culture.

This study is drawn from a case study of the Ionic frieze in Parthenon, Athens, considered both a textile and spatial storytelling device. The research method applied in this paper consists of a literature review of references on the ideas on the links between textile-making and architectural ornament by Gottfried Semper, as well as the historical development of the frieze in both textile weaving and classical architecture.

The paper concludes that the significance of the religious Panathenaia festival is not merely depicted by the peplos identified on the central east Ionic frieze, but is also expressed in the entire representational scheme of the Ionic frieze, along with the overall spatial configuration of the Parthenon. Architecture, instantiated by the Parthenon, is regarded as spatial–textile storytelling to communicate meanings.

Keywords

Frieze ; Spatial–textile storytelling ; Medium ; Mediating ; Panathenaia festival

1. Introduction

This paper is based mainly on a discussion of how the frieze metamorphosed from textile to marble storytelling material in architecture and how it contributes to achieving spatial–textile storytelling in the Ionic frieze and the Parthenon. Section 2 is a general discussion of Gottfried Semper׳s idea that original architecture metamorphosed as a meaningful activity of man, from the weaving of branches to the analogous application of stones. In addition to Semper׳s idea, the discourse introduces the frieze in classical architecture and in Ancient Greece as textile storytelling by employing the Panathenaia peplos as the narrative device. Section 3 is a case study of the Ionic frieze in Parthenon, in Greece, as a spatial–textile storytelling device. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2. Weaving the frieze

2.1. Weaving architecture: from branch to stone

For Roland Barthes, architecture is a sign, such that, a building is more than a collection and composition of structural constructive elements: walls, floors, windows, pillars, and ceilings (Barthes, 1977 ). According to Barthes, architectural elements only serve functional purposes. This definition does not concern the relationship of human beings with the building or the architecture, to put it more formally. Architecture cannot be considered as an arbitrary linguistic sign because humans use it all the time. In addition to viewing architecture from outside, humans inhabit it, which signifies different meanings, such as home, warmth, entertainment, and safety among others. This definition prompts the question – if architecture is more than a sign, what does it mean to us?

According to Gottfried Semper, the origin of architecture lies in “man׳s urge to bring the structure of his world to articulate and to sustain this world through embodied representation (cited in Hvattum, 2004 , p. 13),” which involved “not only a genealogy of art, but also speculations on the origin of society (p. 13).”

For Semper, the history of architecture begins with a history of practical art which, in turn, begins with “motifs simultaneously embodying function, techniques and ritual action (Hvattum, 2004 , p. 10).” After his observation of the primary elements of architecture, namely the hearth, mound, roof, and wall—, Semper indicated that each of these elements “corresponds to a particular technique of making, developed both in a ritual and a functional sense in the practical arts (p. 14).” The hearth originated in the firing of clay that consequently evolved into ceramic techniques. Stonework developed into the mound, and carpentry into the roof. The enclosure that originated in the wickerwork of walls was associated with weaving techniques. The key element that contributed to Semper׳s development map of primary architectural elements was the wall motif. The original enclosure, as Semper argued, “was not the solid wall or wood, but rather the primitive fence woven by branches and grass (Semper, 1989 , pp. 103f).” For Semper:

Wickerwork, as the original space divider, retained the full importance of earlier meaning, actually or ideally, when later the light mat walls were transformed into clay tile, brick, or stone walls. Wickerwork was the essence of the wall (Semper, 1989 , p. 103).

Therefore, the wall motif, as it originated from practical art, coincided with weaving, that is, textile art (Rykwert, 1995 , p. 30).

2.2. The frieze in classical architecture

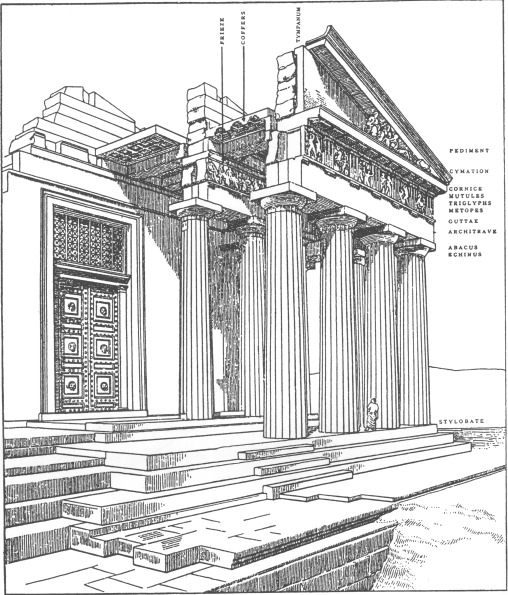

Classical architecture consists of five primary orders: the Doric, Ionic, Tuscan, Corinthian, and the Composite. Even as each order embodies a different meaning, each possesses the same system of architectural composition, including the base, shaft, capitals, and entablature, from the bottom to the top.

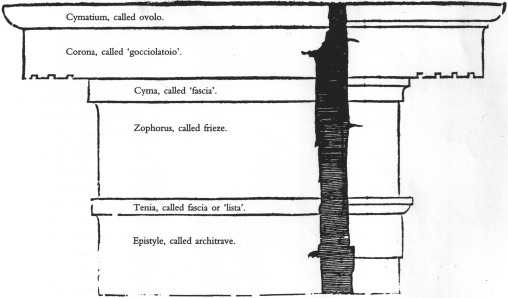

The top section of the order, the “entablature”, is the section where the frieze settles. According to Sebastiano Serlio (1996) , the entablature is composed of six main parts: architrave, fascia, frieze, fascia, cornice, and cymatium (Figure 1 ; from bottom to top, respectively). Joseph Rykwert (1996, p. 182) stated that “frieze” is the modern name for the middle section of the entablature, derived from a corruption of the Latin phrygiones that refers to an embroidered dress, or just an embroidered hem, which imitated the kind of work that the Phrygia women in Central Anatolia were considered particularly good at. Appearing in architecture in the 16th century, the antiqueue technical term for a frieze was zōphoros , which was transliterated from Greek to Latin and portrayed animals and figures, and from Latin to the Italian, fregiare , meaning “to decorate” ( Rykwert, 1996 , p. 182).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Composition of entablature, from bottom to top: architrave; fascia; frieze; fascia; cornice; cymatium (Source : Serlio, 1996 , p. 258).

|

For Vitruvius, the heights of the friezes, which functions as beams, varies according to the representations they contained. A frieze with figures was 25% higher than the architrave so that the sculpture can carry more authority, whereas a frieze with no figures was 25% lower than the architrave. The content or representation of the frieze varies in the five orders. The Doric frieze consists of triglyphs and metopes. Triglyphs are “the slight projections at intervals, on which are cut three angular flutes (Parker, 1986 , p. 120).” Metopes are the “intervals between triglyphs which are frequently enriched with sculptures (p. 120).” The Ionic frieze is a continuous band occasionally enriched with sculptures, and is sometimes “made to swell out in the middle when it is said to be cushioned or pulvinated (p. 120).” The Tuscan frieze is normally plain. Moreover, Corinthian and Composite friezes are “ornamented in a variety of ways but usually either with figures or foliage (p. 120).”

2.3. Weaving the Panathenaia peplos: the frieze as a textile–storytelling device in Ancient Greece

With reference to Semper, the wall, as one of the four primary architectural elements, originated from weaving techniques. However, the meaning of frieze in Classical architecture pertains to decoration. Thus, how can the frieze be woven as in textile storytelling?

In ancient times, the Athenians held an annual festival to express their gratitude to the goddess Athena, the patron of their city, and every four years Athenians held a “particular large version of the festival which was named the Great Panathenaia (Barber, 1992 , p. 112).” One of the central features of the Panathenaia festival was the presentation of a specially woven, rectangular woolen tapestry to the statue of Athena. This woolen tapestry, called the “Panathenaia peplos” was always decorated with the “figures of Athena and Zeus leading the Olympian gods to the victory in the epic Battle of the Gods and the Giants (p. 112).” Usually, nine months before the Great Panathenaia, four girls, probably between the ages of seven 7 and 11, were selected from aristocratic Athenian families to live on the Acropolis for one year to weave the peplos, which was presented to the goddess Athena during the Great Panathenaia festival (p. 113).

According to Mansfield, “Frieze clothing is widely attested and is represented among artifacts found on the Acropolis (Mansfield, 1985 , p. 116).” There were two design forms of the Panathenaia peplos:

One comprised of successive scenes in a series of continuous horizontal friezes going the entire width of the cloth. The one is square panels in a ladder-like arrangement of a dozen small picture-boxes going down the front of the garment (Mansfield, 1985 , p. 115).

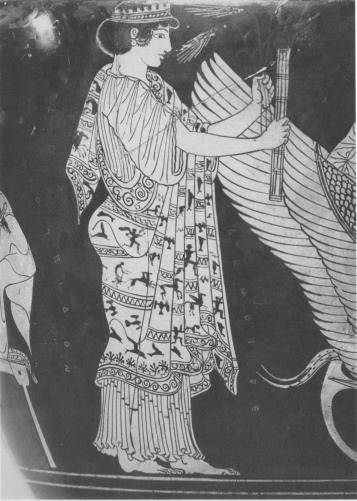

Determining which design was used was not particularly important because the point was to appreciate that sometimes one form was chosen and sometimes the other (Mansfield, 1985 , p. 116). The peplos representing a continuous horizontal story frieze of human and animal figures was commonly worn by Ancient Greek princesses and goddesses as a fashion item (Figure 2 ). The ladder-like frieze type of peplos was, however, worn less often by women (Figure 3 ). Regardless of which form of frieze was selected for the peplos, the dominant color on the peplos was saffron yellow, the color associated with women throughout Greek mythology and tradition.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Horizontal style of frieze (Source : Neils, 1992 , p. 115).

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. Ladder-like frieze (Source : Neils, 1992 , p. 115).

|

To summarize, “the entire ritual of presenting Athena with an ornate new dress was a local relic of the Bronze Age (Mansfield, 1985 , p. 117).” By representing the friezes of the Panathenaia peplos, both horizontal and ladder-like, weaving ritually occupied an integral place in the lives of Athenians, particularly among women. Therefore, the frieze not only functioned as a decorative section on five orders of classical architecture, it was also positioned as an important style of textile storytelling in Ancient Greece, especially the Panathenaia peplos. Based on the above discussion, how was the frieze metamorphose considered as spatial–textile storytelling in architecture? This question is addressed in Section 3 .

3. Weaving the Panathenaia: Ionic frieze on the Parthenon as spatial–textile storytelling

Recalling that the frieze functioned in five Classical orders, this study refers to the Ionic frieze to identify the continuous style of the frieze on the Ionic temples and the Parthenon.

3.1. The Panathenaia in Ancient Greece

In defining their common brotherhood with other Greeks, the citizens of the ancient polis or city-state of Athens, according to the historian Herodotus, cited their shared language and the altars and sacrifices of which we all partake – in short, their common religion (Neils, 1992 , p. 13).

For Ancient Greeks, organized religion centered neither on a sacred text, such as the Bible or the Qur’an nor on the comprehension of abstract dogmas of creed, instead, it was comprised “principally of actions: rituals, festivals, processions, athletic contests, oracles, gift-giving and animal sacrifices (Neils, 1992 , p. 13).” In ancient Athens, one third of the calendar year, or approximately 120 days, was devoted to festivals. The Panathenaia, translated as “rites of all Athenians (Noel, 1996 , p. 57),” was the most important festival celebrated in Ancient Greece; it was believed to be the state festival honoring the city׳s patron deity: Athena Polis (“Athena of the city”) (Neils, 1992 , p. 13), to celebrate the birthday of the goddess Athena.

In 566 BCE , “on the model of the four-yearly festivals at Plypia and Delphi (Neils, 1996 , p. 8),” the Great Panathenaia was created by Pisistratus, a tyrannical ruler of Athens from 546 to 527/8 BCE . Therefore, every four years, the Panathenaia festival was extended over a number of days, with numerous public events consisting of three elements: procession, contests, and sacrifices. In addition to these activities, one of the central features of the festival was the presentation of the peplos – a specially woven, rectangular woolen cloth decorated with scenes of battles between the gods and the giants of Greek mythology – to the wooden statue of the goddess.

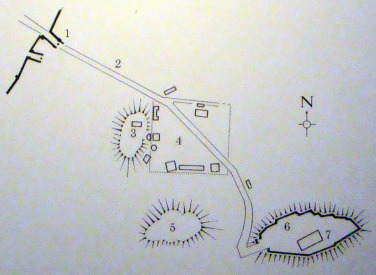

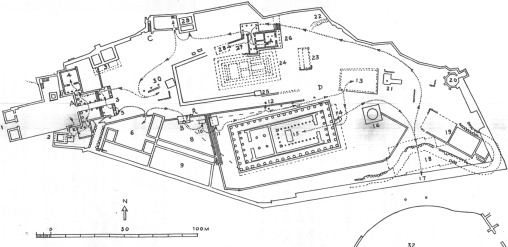

The Panathenaia procession brought together all the inhabitants of the city and the suburbs – young and old, citizens and non-citizens, men and women, soldiers and civilians – to participate in the festival. The starting point of the procession was the Dipylon Gate, which means “double gateway,” at the north-western side of the city. According to the text board in the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum, the procession moved through the potters’ quarter, along the straight road that led into the market place, or agora . Passing through the agora , the procession continues until it arrived at the Acropolis; the great rock situated in the city center (Figure 4 ).

|

|

|

Figure 4. Route of Panathenaia procession in Ancient Greece (Source : text board in Duveen Gallery, British Museum; photo by researcher).

|

3.2. Background information on the Ionic frieze

Unlike a church or mosque, a Greek temple was not normally designed for a congregation. Intended primarily to shelter the image of the divinity to whom it was dedicated, a temple also functioned to secure the property of the divinity, such as the sacred or precious vessels used in their cult, or the votive offerings brought by their worshippers. The Parthenon, without exception, was the place for the statue of Athena. In addition, the Parthenon was “in itself a votive offering which was made in gratitude for past benefit or for the favors yet to come (Corbett, 1959 , p. 8).”

Designed by the architects Ictinus and Callicrates, even though the Parthenon is a Doric temple, it is distinguished from other Doric temples by its exceptional sculptural decoration of the continuous Ionic frieze. A continuous frieze on one face of a Greek temple was normally concerned with one single subject, but if all the faces of the temple were decorated with sculptures, the subjects of different faces were often independent and unconnected.

Such a design, developed over all sides through figures of different kinds variously engaged but all united in one purpose, is found in the Parthenon frieze, and it has no parallel (Robertson and Frantz, 1975 , p. 7).

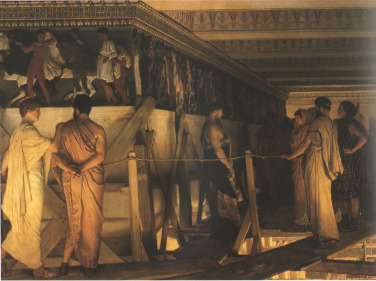

Carved on the upper section of the four side walls of the Parthenon cella, the Ionic frieze was positioned 12 m above the base. Unlike the pediments, which were carved independently in workshops, and some of the separate, single-block metopes, which can be carved on the ground, the Ionic frieze was carved directly onto the wall (Figure 5 ). Given that there are four faces of the Parthenon cella, the Ionic frieze naturally has four sequences; north, south, west, and east. Consisting of 115 single slabs, the total length of the Ionic frieze is 160 m. At 1-m high, the Ionic frieze was carved in low relief 6 m deep above the surface of the wall. The background of the slabs was of a deep blue color, and the style of the relief was richly colored with metal attachments (Figure 6 ).

|

|

|

Figure 5. Perspective section of east side of the Parthenon (Source : Tournkiotis, 1994 , p. 352).

|

|

|

|

Figure 6. Phidias and the Parthenon (Source : Tournkiotis, 1994 , p. 236).

|

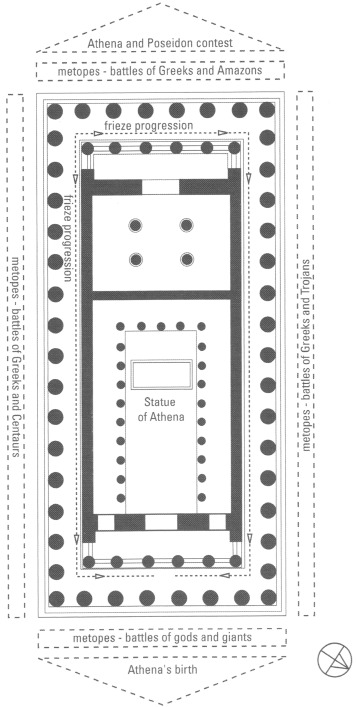

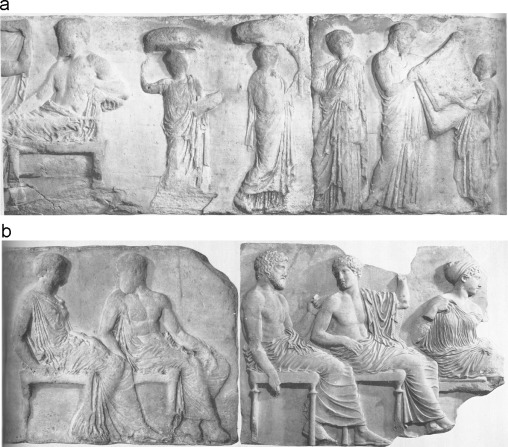

The Ionic frieze depicted the Panathenaia festival procession. According to its subject and sequence, the procession was divided into four parts on the Parthenon (Figure 7 ). Starting at the south-west point of the inner space of the building, the progression followed two routes: one along the south side and the other one along the west and the north sides, meeting at the midpoint of the east side of the cella. The west Ionic frieze was regarded as the procession preparation and was occupied with scenes of long rows of knights on horseback, many of which are grouped loosely, some mounted and some preparing themselves or their beasts. The north and the south Ionic frieze, which constituted the long sides of the Parthenon cella, depicted the procession moving in an easterly direction, with “varied participating groups loosely but not mechanically balanced on north and south (Robertson and Frantz, 1975 , p. 7).” The east Ionic frieze, which is the central and culminating face of the whole, exhibited the dedication of the peplos to the goddess (Figure 8 ).

|

|

|

Figure 7. Plan of the Parthenon showing progression of procession on the frieze, and thematic content of metopes and pediments (Source : Psarra, 2009 , p. 22).

|

|

|

|

Figure 8. (a) East face of Ionic frieze in the Parthenon (Source : Robertson, 1975 , p. 30); (b) central east face of Ionic frieze in the Parthenon (Source : Robertson, 1975 , p. 31).

|

Even though the representation of the Ionic frieze is believed to portray the procession of the Great Panathenaia festival, some argues about the authenticity of the Ionic frieze.

It is indeed difficult to decide how far the frieze can be regarded as true to life; though the general character and many of the details tally with ancient statements about the Panathenaic procession and so support the identification of the subject, the agreement is not complete (Corbett, 1959 , p. 22).

Some details are confirmed by historical accounts; “the most striking instance is the absence of the citizen infantry in full armor (Corbett, 1959 , p. 22).” Figures dominate the whole Ionic frieze – mortals, immortals, and animals – rather than the festival setting. Such expression was usually adopted in the Greek art of that time. In addition, the Ionic frieze sequence, which mirrors the procession order, starting from the secular display of cavalry and chariots to the sacrificial animals, onto the gods, more or less indicated that the progression of the depiction was intentionally designed (p. 22). Hence, all these arguments prompted the belief that:

Although the frieze is based on actuality, the whole subject and its various components have been shaped and remolded into harmony by a powerful and sensitive mind (Corbett, 1959 , p. 23).

Thus, the Ionic frieze is a mediation of the Panathenaia festival by Ancient Greek artists through marble as a visual storytelling. Made of marble, carved on the exterior walls of the Parthenon cella, and distinguished from the Panathenaia festival as recorded by verbal or written storytelling, the Ionic frieze on the Parthenon provides “an ideal embodiment of a recurrent festival (Neils, 1996 , p. 11).” Hence, the frieze, as a device for depicting significant human events, transforms from its original material from textile to marble. Moreover, the Ionic frieze was not merely a visual storytelling device but also part of the Parthenon cella. Therefore, the Panathenaia festival was depicted on the Ionic frieze, as well as in the Parthenon space. If the Ionic frieze was considered as a tangible medium to depict the festival, it was shown that space, as an intangible medium, depicted the festival.

3.3. The Parthenon as a spatial storytelling medium of the Ionic frieze

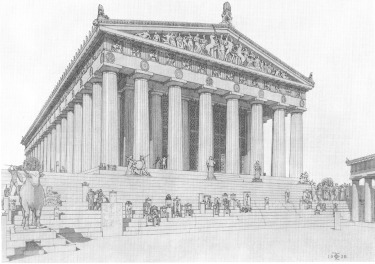

Situated on the south-east side of the Acropolis, the Parthenon needs to be approached by climbing the slopes of the Acropolis to the monumental gateway, the Propylaea (Figure 9 ). On approaching the temple, the temple itself provided the visitors with two orders of interpretation process: the Doric and the Ionic orders as the bearing and the superstructure systems, respectively. As people moved to the temple via the stairs, the first indication of the Ionic order was the eight frontal columns along the short sides of the building, presented as Doric types (see Figure 10 ) (Tournkiotis, 1994 , p. 87).

|

|

|

Figure 9. Plan of the Acropolis (Source : Corbett, 1959 , p. 6).

|

|

|

|

Figure 10. View from the Propylaea (Source : Psarra, 2009 , p. 28).

|

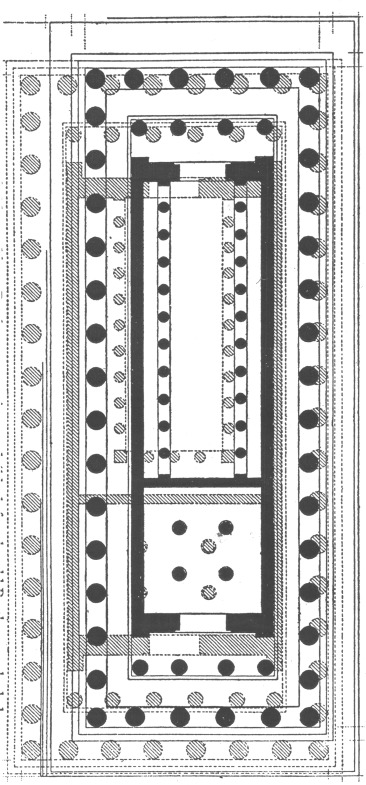

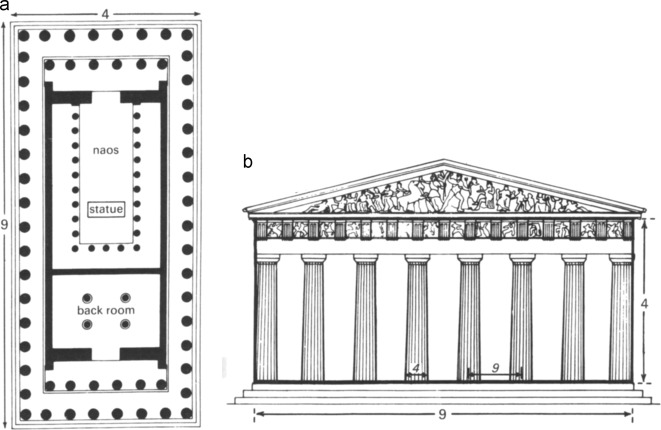

The Periclean Parthenon was constructed on the base of the Old Parthenon, which was destroyed by the Persians (Figure 11 ). Compared with the old plan, the new plan was slightly wider. The former emphasized that the longitudinal axis of the old plan was reduced. The spaces within the cella and the west chamber were both enlarged in proportion to their length. The new plan added more columns on both sides of the peristyle, and the new Parthenon used octastyle instead of hexastyle along each short side, adding one more column along each long side. With 8 and 17 columns on the short and long sides, respectively, the colonnaded space density increased. The height, width, and length of the temple, and even the relationship of the columns to the spaces between them, were linked in a proportion of 9:4 (see Figure 12 ) (Woodford, 1981 , p. 17). From the new ratio of 9:4, a new proportional system was applied throughout the other parts of the building, bestowing a much greater sense of unity on the design (Bruno, 1974 , p. 77).

|

|

|

Figure 11. Superimposed plans of older and later Parthenon (Source : Bruno, 1974 , p. 61).

|

|

|

|

Figure 12. (a) Plan of the Parthenon showing the 9:4 ratio of width to height; (b) elevation of the Parthenon showing the 9:4 ratio of interaxial to diameter of columns (Source : Woodford, 1981 , p. 17).

|

Such dense arrangement of the columns effectively sustained the colonnaded space of the long sides. If the distances between each column were not sufficiently narrower than the distance between the columns and the walls of the cella, the colonnaded space—as the first, semi-open place that transformed the exterior to the interior – loses its coherence and becomes confused with the space outside. The two forces between the cella and the colonnaded space included the force from the wall which pushed the colonnade space outside to increase the interior size of the cella and made the wall as close to the columns as possible; the other was the force held in the colonnaded space formed by the remarkable density of the columns (Tournkiotis, 1994 , p. 90). The colonnaded space was not merely a rectilinear space but a space that flowed around the cella. Hence, the Ionic frieze along the four sides of the cella was sustained by the force created by the colonnaded space.

In addition to this unique feature, the two other features which made the temple so rare: one was that the pronaos and opisthodomos were almost the same size, whereas in other temples the pronaos was usually deeper than the opisthodomos; the other was that both the pronaos and opisthodomos were prostyle, not in antis, as in other traditional temples (Tournkiotis, 1994 , p. 92). Hence, the pronaos and opisthodomos became transitional spaces between the colonnaded space and the cella, and the colonnaded space and the west chamber. The spatial innovations contributed to the creation of the sacred atmosphere of the temple, particularly the Ionic frieze. The focus shifted gradually from outside to the semi-open colonnade space, and from the colonnaded space to the pronaos. The prostyle of the western and eastern sides of the cella hinted at the meanings of the relevant sequence of the Ionic frieze; the preparation for the Panathenaia procession was depicted on the west Ionic frieze, and the presentation of the peplos was displayed on the east Ionic frieze.

Compared with the Old Parthenon plan, the spaces within the cella were enlarged and the interior design was altered. In the old plan, the interior space of the cella was divided into three aisle spaces, with two narrow aisles on each side and one wide aisle in the center. In contrast, the transverse colonnades connected the longitudinal colonnades at the rear of the cella in the new plan, thereby creating a continuously flowing, three-sided composition (see Figure 7 ) (Bruno, 1974 ). Additionally, as it was designed as the place to store the statue of Athena, the three-sided colonnaded space offered a background for the goddess. Hence, regardless of whether it was the interior space of the cella in which the statue of Athena was situated, or the colonnaded space surrounding the cella in which the Ionic frieze was located, both spaces conferred significance to the function of the Parthenon, not only as a place to house the statue of the goddess and any votive offering dedicated to the goddess, but also as a tangible place to display and pass on their culture and memories.

Very few scholars have discussed the lighting conditions in the Parthenon. One scholar, James Fergusson, wrote an essay entitled “The Parthenon: An essay on the mode by which light was introduced into Greek and Roman temples (Fergusson, 1883 ).” However, the essay focused more on the lighting of the interiors of the Parthenon and other Greek temples, rather than on the Parthenon sculptures, particularly the Ionic frieze. Majority of the Parthenon sculptures are positioned either on the exterior colonnades or on the roof. As such, how can this be viewed with regard to the Ionic frieze at 12 m above the ground along the cella?

Positioned behind the metopes, light was introduced from the exterior colonnades (Figure 5 ). From 2010 to 2011, according to the author׳s personal interviews along with Evelyn Vouza, an archeologist working in the Parthenon Gallery in the New Acropolis Museum, Athens, the roof above the Ionic frieze, which was the roof of the colonnaded space, was made of light marble. Therefore, sunlight, which can be gently mediated by the marble roof, was projected onto the Ionic frieze. Thus, the top area of the colonnaded space was not completely dark but was immersed in a gentle light. It can be conceived that the lighting conditions of the Ionic frieze were totally different from those of the other Parthenon sculptures. The Parthenon sculptures exposed to direct sunlight were the focus of the Parthenon when viewed from the outside, but the Ionic frieze, as a part of the Parthenon cella, communicated the meaning of the temple in a mediated lighting condition – a temple as an artifact dedicated to the goddess Athena. Therefore, the frieze, as a device communicating significant events, was transformed from its original form in the tangible textile material to a visual form in the tangible marble material, and finally, to spatial form in the tangible architectural space. The significant event—the Panathenaia festival—was recorded from textile storytelling to visual and spatial storytelling.

4. Conclusion

4.1. Weaving culture: the significance of spatial–textile storytelling

According to Semper, architecture can be regarded as the creative product of the weaving activity and as textile storytelling, where the Panathenaia peplos can be considered the extended ritual product of the weaving activity. Similarly, the Ionic frieze was the ritual product of the weaving activity. With regard to the Panathenaia peplos, friezes – the continuous horizontal and the ladder-like or metope-like friezes – were different styles of textile storytelling. Consequently, the peplos in the Ionic frieze was a permanent ritual symbol identified on the central east Ionic frieze, indicating the significance of the Panathenaia festival.

The Panathenaia festival, as an actual event, occurred primarily in the Acropolis. It was afterwards mediated by the Panathenaia peplos (tangible textile as textile storytelling), then by the Panathenaia procession (marble Ionic frieze as visual storytelling), and eventually by the Parthenon (as spatial–textile storytelling). The religious Panathenaia procession as the subject of the Ionic frieze was “unique in such a context, as indeed is almost every aspect of this extraordinary monument (Robertson and Frantz, 1975 , p. 95).” Storytelling, as a meaningful cognitive action generated by humans, contributed to conveying the meanings of significant human events using diverse forms of different tangible materials.

Regardless of whether the Panathenaia peplos or the Ionic frieze was referred to, both were tangible media that depicted the significance of the Panathenaia. The difference between the Ionic frieze and the Panathenaia peplos was the medium of representation. The significance of the religious Panathenaia festival was not merely depicted by the peplos identified on the central east Ionic frieze, but by the entire Ionic frieze representation and the Parthenon space. The achievement of the Parthenon masters did not bring the development of art and architecture to a standstill by inspiring mere imitation. On the contrary, “the immediate effect of the Parthenon was to stimulate originality and experimentation (Bruno, 1974 , p. 95).”

The Panathenaia festival, the Panathenaia peplos, the Ionic frieze, and the Parthenon were artifacts created by the Ancient Greeks. Within these artifacts, storytelling, as the ability of human beings to communicate with the outside world, evolved from verbal to spatial and from cognitive activity to embodied experience. The significance of the ritual Panathenaia has been constantly mediated by the tangible and intangible media of either the content or the representation of the storytelling. Human beings are neither non-participating spectators nor surveyors of the surrounding world, but are authentic makers, “weaving” and experiencing culture. The Parthenon, as a spatial–textile storytelling medium, tangibly mediates the culture it represents. This may be where the significance of architecture rests – as a creative product of human activity that simultaneously shapes human lives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundamental Funds of the Humanities and Social Sciences of the Beijing Jiaotong University China under the Grant KAJB13007536 .

References

- Barber, 1992 E.J.W. Barber; The Peplos of Athena; J. Neils (Ed.), Goddess and Polis: The Panathenaic Festival in Ancient Athens, Princeton University Press, New Jersey (1992), pp. 103–117

- Barthes, 1977 R. Barthes; Elements of Semiolog, translated From the French by A. Lavers and C. Smith; Hill & Wang, New York (1977)

- Bruno, 1974 Bruno, J.V., 1974. The Parthenon: Illustrations, Introductory Essay, History, Archaeological Analysis, Criticism. Norton, New York.

- Corbett, 1959 E.P. Corbett; The Sculpture of the Parthenon; Penguin, UK (1959)

- Fergusson, 1883 J. Fergusson; The Parthenon: An Essay on the Mode by Which Light Was introduced into Greek and Roman Temples; John Murray, London (1883)

- Hvattum, 2004 M. Hvattum; Gottfried Semper and the Problem of Historicism; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (2004)

- Mansfield, 1985 J. Mansfield; The Robe of Athena and the Panathenaic Peplos (pH.D. thesis); University of California, Berkeley (1985)

- Neils, 1992 J. Neils; Goddess and Polis: The Panathenaic Festival in Ancient Athens; Princeton University Press, New Jersey (1992)

- Neils, 1996 J. Neils; Worshipping Athena: Panathenaia and Parthenon; University of Wisconsin Press, Wisconsin (1996)

- Noel, 1996 R. Noel; Athena׳s shrines and festivals; J. Neils (Ed.), Worshipping Athena: Panathenaia and Parthenon, University of Wisconsin Press, Wisconsin (1996), pp. 27–77

- Parker, 1986 H.J., Parker, 1986. Classic Dictionary of Architecture: A concise glossary of terms used in Grecian, Roman, Italian, and Gothic architecture, revised fourth ed. New Orchard Editions, New York.

- Psarra, 2009 S. Psarra; Architecture and Narrative: The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning, Routledge, Oxford (2009)

- Robertson and Frantz, 1975 M. Robertson, A. Frantz; The Parthenon Frieze; Phaidon, London (1975)

- Rykwert, 1995 J. Rykwert; On Adam׳s House in Paradise: The Idea of the Primitive Hut in Architectural History; MIT Press, Cambridge, MA (1995)

- Rykwert, 1996 J. Rykwert; The Dancing Column: On Order in Architecture; MIT Press, Cambridge, MA (1996)

- Semper, 1989 G. Semper; The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings; H.F. Mallgrave, W. Herramann (Eds.)Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (1989)

- Serlio, 1996 S. Serlio; Sebastiano Serlio on Architecture; H. Vaughan, H. Peter (Eds.)Yale University Press, Connell, USA (1996)

- Tournkiotis, 1994 P. Tournkiotis; The Parthenon and its Impact in Modern Times; Harry N. Abrams, New York (1994)

- Woodford, 1981 S. Woodford; The Parthenon; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (1981)

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?