Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Intervention against cyberbullying and other risks associated with the misuse of ITC and social networks is an important social demand. The «Asegúrate» Program tries to support teachers in this intervention. This research shows the impact of the program among those that have shown to be less sensitive to other ones: cyber-aggressors. Concretely, the impact of the program on the prevalence of aggression in cyberbullying and bullying, sexting and abusive use of the Internet and social networks are analyzed. The evaluation of the program was carried out with a sample of 479 students (54.9% girls) of Compulsory Secondary Education (age M=13.83. SD=1.40) through a quasi-experimental methodology, with two measures over time. The instruments used were the “European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire”, the “European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire”, the ”Internet Related Experiences Questionnaire” and two items about sexting involvement. The results show that the involvement in cyber aggression, sexting, and intrapersonal dimension of abusive use of Internet and social network increases without intervention, whereas it diminishes when the intervention is carried out. Moreover, a significant decrease in the aggression and cyber aggression among cyber aggressors is evidenced. Thus, “Asegúrate” Program is effective for decreasing the prevalence of aggressions and cyber aggressions as well as the involvement in other phenomena considered cyberbullying risk factors.

1. Introduction

1.1. Cyberbullying and its associated risks

Cyberbullying is an emerging phenomenon defined as repeated harm arising from the widespread and generalized use of digital media to communicate with others and engage in social life (Hinduja & Patchin, 2008). Many researchers have approached this construct by holding it up against its counterpart in the physical world (Garaigordobil, 2015), namely bullying, which has an established scientific background (Prodócimo, Cerezo, & Arense, 2014). In fact, despite their differences, primarily owing to the contexts in which they take place (Vannucci, Nocentini, Mazzoni, & Menesini, 2012), we now know that a high degree of co-involvement exists between them (Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015). Previous research on Spanish samples report some diverging prevalence trends. In the most recent study conducted with a representative sample of Spanish adolescents (Sastre, 2016), involvement was 10.2% (3.3% cyber aggression and 6.9% cybervictimization). This figure surpasses the 7.7% found by Cerezo, Arnaiz, Giménez, and Maquilón (2016). These data become dispersed when addressing the various forms, declining in the most serious cases (Álvarez-García, Barreiro-Collazo, & Núñez, 2017).

The efforts that go into understanding these behaviors reveal risk factors for cyber aggressions (Modecki, Barber, & Vernon, 2013). Those of particular relevance when it comes to psychoeducational interventions include the abusive use of social networks and sexting (Del Rey, Casas, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2012). Regarding abusive use, “smartphones” have led to a general increase in time online, especially among the younger populations (Colás, González, & de-Pablos, 2013). Despite this, the actors involved in cyberbullying, particularly cyber aggressors, continue to spend significantly more time connected than their non-involved peers (Hinduja & Patchin, 2008). Sexting, understood as the sending and receiving of messages, images and videos of a sexually explicit nature on a technological device, especially mobile phones (Klettke, Hallford, & Mellor, 2014), deserves special attention not only for being a risk factor for cyberbullying (Livingstone & Smith, 2014), but also for the impact it has in its own right (Korenis & Billick, 2014). What is more, sexting involvement is on the rise among Spanish adolescents (Gámez-Guadix, de Santisteban, & Resett, 2017).

1.2. Interventions against cyberbullying and its associated risks

The need to intervene in cyberbullying is, beyond all doubt, a priority in the current climate given the figures and consequences related to this phenomenon (Ortega, et al., 2012). Empirical findings to date have shown that school-based anti-bullying programs are partially effective in tackling cyberbullying (Williford & al., 2013). However, there is also evidence supporting the view that specific content associated with virtual environments and social networks (Del Rey, & al., 2012) as well as sexting (Hinduja & Patchin, 2012) needs to be introduced.

Steps towards addressing cyberbullying in Spain have gradually been taken. The first public interventions have involved adapting school-based anti-bullying protocols and “convivencia” projects (promoting harmonious interaction) within the cyberbullying domain (Cerezo & Rubio, 2017). One such initiative currently underway is the 2016 Strategic Plan for School Co-existence coordinated by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, which prioritizes violence prevention, teaching how to use information and communication technologies (ICT) and teacher training. On this topic, it has been shown that teachers’ feelings of competence are key to reducing bullying and cyberbullying (Casas, Ortega-Ruiz, & Del Rey, 2015; Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017).

Anti-cyberbullying interventions have also been developed and empirically tested with adolescents. These include Cyber program 2.0 (Garaigordobil & Martínez-Valderrey, 2015) and ConRed (Del Rey, & al., 2012), which have proven to be effective in reducing both cybervictimization and cyber aggression as well as bullying and other risks. The ConRed program has even demonstrated its impact on cyber aggressors (Del Rey, Casas, & Ortega, 2016). However, little is still known about their impact on the prevalence of cyber aggression, which is one of the most difficult objectives to achieve in bullying interventions (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011).

1.3. The “Asegúrate” Program

The “Asegúrate” Program was created to help teachers intervene against cyberbullying and its associated risks. It was also conceived to enhance their feelings of competence in this area. The program is structured around three main pillars:

a) The theory of normative social behavior (Rimal & Lapinski, 2015). This highlights how social behavior is significantly influenced by social norms, where we see changes in conduct that lead to adopting external conventions and patterns, in addition to avoiding dissent. It upholds the notion that our behavior is likely driven by what is perceived as socially acceptable, normal and legal (Del Rey, & al., 2012). Thus, adolescents behave with their peers on social networking sites (as well as in face-to-face interactions) according to how they perceive relationship norms in online settings, where bad relationships occur as a way of mimicking or blending in with the context guided by three normative mechanisms: group identity, expectations and recognized legal norms. Recognizing these keys and positively returning them to the students would be essential in ensuring a successful intervention. “Asegúrate” makes use of the following processes in intervention design: first, it presents positive identification models to the group, highlighting how some behaviors do not entail improved integration among peers; second, it examines students’ expectations in everyday situations and holds them up against the real effects that bad relationships and online bullying have; and third, it analyzes habitual online norms and works alongside students to assess their impact.

b) Self-regulation skills. The inclusion of reflective practice in psychoeducational programs, aimed at enhancing metacognitive skills, has been carried out successfully for some time now (Joseph, 2009). It has been found that people with lower self-regulation skills are more likely to engage in aggressive behavior and are less capable of gauging the consequences their actions have on others (Roncero, Andreu, & Peña, 2016). In the specific case of cyberbullying, a link between low self-regulation and involvement (Vazsonyi, Machackova, Sevcikova, Smahel, & Cerna, 2012) and between less developed metacognitive skills and the use of non-productive coping strategies (Nacimiento, Rosa, & Mora-Merchán, 2017) has also been observed. Thus, it is necessary to include elements that allow and invite us to reflect on our actions, particularly during adolescence, which is a developmental period characterized by lower self-control and greater impulsivity (Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008). These elements are especially relevant when it comes to online communication, given the perceived anonymity, limited consequences and invisibility, which can lead to less inhibitory control and, therefore, increased cyber aggression (Van-Royen, Poels, Vandebosch, & Adam, 2017).

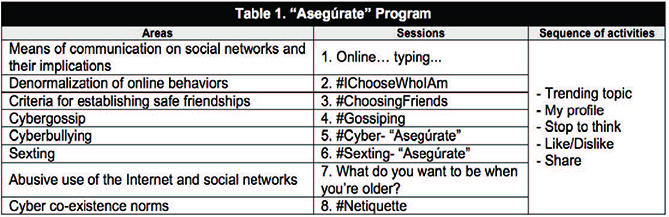

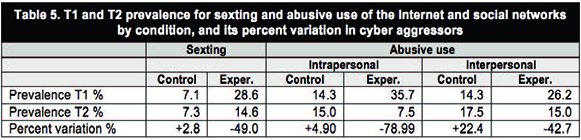

c) The ideas/beliefs held by adolescents. Adhering to the principles of constructivist methodologies (e.g., Powell & Cody, 2009), the sequence of activities (Table 1) is based on identifying pre-existing ideas about virtual environments, in particular, social networks. This is followed by an analysis of one’s behavior in these settings. Next, the emphasis is placed on reflecting on the reasons behind these behaviors. The following step is to analyze the potential consequences of the behaviors exhibited by those at both the giving and receiving ends. The sequence concludes with an activity that seeks to generalize and transfer the achievements to other relationship contexts. All of these tasks adopt a reflective approach, which is necessary for progressively reshaping the students’ beliefs and expectations. This fixed sequence of activities across all sessions allows the teacher, who is responsible for implementing the program, to devise their units of work following a common logic, which can be adapted to the students’ characteristics.

1.4. Aim and objectives

Because this represents a new program and its effectiveness is yet to be determined, particularly among those who have shown to be less sensitive to other programs, the aim of the present study was to analyze the impact of “Asegúrate” on aggression in cyberbullying and bullying, as well as on two of the associated risk factors: sexting and the abusive use of the Internet and social networks. Specifically, we sought to identify the program’s impact relating to three specific objectives: a) the prevalence of aggression in cyberbullying and bullying, sexting, and abusive use of the Internet and social network; b) the intensity of cyber-aggressive and aggressive behaviors; and c) cyber aggressors’ involvement in the risk factors under consideration: sexting and the abusive use of the Internet and social networks.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Four hundred and seventy-nine (479) students aged 12 to 18 years (54.9% girls; M=13.83, SD=1.40) from seven secondary schools in Andalucía (southern Spain) took part in this study. Among them, 292 belonged to five schools assigned to the quasi-experimental group (57.4% girls; M=13.84, SD=1.42) and 187 belonged to two schools assigned to the control group (51.1% girls; M=13.84, SD=1.35).

2.2. Instruments

The aggression subscale pertaining to the “European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire” (ECIPQ; Del Rey & al., 2015) was used to assess cyber aggression. It comprises 11 items that assess the frequency of cyber aggression in the last two months, eliciting Likert-type responses (0=No; 1=Yes, once or twice; 2= Yes, once or twice a month; 3=Yes, around once a week; 4=Yes, more than once a week). Example: “I’ve insulted someone on social networks or WhatsApp”. Reliability of this subscale in the present study was a=.72.

The aggression subscale corresponding to the “European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire” (EBIPQ; Ortega-Ruiz, Del Rey, & Casas, 2016) was used to assess bullying. It comprises seven Likert-type items and evaluates the frequency of aggression using the same response options as the previous measure. Example: “I’ve insulted and said offensive things to someone”. Reliability of this subscale was a=.72.

A method applied in previous research (e.g., Ybarra & Mitchell, 2014) was used to assess sexting involvement. Students were asked to respond to two items, rating their agreement across seven Likert-type options (0=Strongly disagree to 6=Strongly agree). The statements were: “I’ve sent sexually explicit videos, images and messages to my boyfriend/girlfriend” and “I’ve received sexually explicit videos, images, and messages from my boyfriend/girlfriend”.

The “Questionnaire of experiences related to the Internet” (CERI; Casas, Ruiz-Olivares, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2013) was used to assess the abusive use of the Internet and social networks. This Internet-related experiences questionnaire comprises ten Likert-type responses with four options (1=Never; 2=Hardly ever; 3=Often; 4=A lot) measuring the intrapersonal dimension (e.g., “When you have problems, do you find that going on social networks or talking via WhatsApp helps you to escape from them?”) and interpersonal dimension of said use (e.g., “Do you find it easier or more comfortable interacting with people via a social network or WhatsApp than in person?”). The reliability in this study was a inter=.70, a intra=.79, a total=.86.

2.3. Procedure

Incidental sampling was performed. Phone calls were made to the schools to request their collaboration. The centres that agreed to sign up were contacted again in order to arrange a meeting and agree on a schedule and the classes that would take part in the study. The questionnaires were administered by young researchers, trained for this purpose, during school hours, and with the prior consent of the teaching staff. Before testing could commence, the voluntary nature of study participation, anonymity, data confidentiality and the importance of giving honest answers were emphasized.

Following initial data collection, time 1 (hereinafter T1), the program was implemented at five schools (quasi-experimental groups) and not at two schools (control groups). The quasi-experimental schools had to commit to implementing at least four of the program’s teaching modules (of their own choosing). Upon intervention completion at the five quasi-experimental centres, the questionnaires were administered again at least three months from the intervention start date – this time at all seven schools, time 2 (hereinafter T2). The schools that did not participate in the intervention were offered the opportunity to do so once the study had concluded.

The research was undertaken in accordance with APA ethical standards and was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Coordinating Committee of Andalucía, which follows the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice set by the International Conference on Harmonization. The project and instruments to be used were presented to the School Board as part of its Co-existence Project and School Improvement Plan, who gave informed consent to participate in the project.

2.4. Data analysis

To achieve the proposed objectives, the first step was to create four dichotomous variables. Two would relate to aggressive involvement in bullying and cyberbullying, following the criteria set out by the authors of the scales used (Del Rey & al., 2015): aggressors were considered to be those who confirmed having shown offensive actions once or twice a month, or more frequent displays of any of the behaviors that present themselves in bullying or cyber-bullying scenarios, respectively. As for sexting, active individuals were identified as those who responded affirmatively to at least one of the two direct items (“I’ve sent sexually explicit videos, images and messages to my boyfriend/girlfriend” and vice versa). The students’ scores were used to create the abusive use of the Internet and social networks variable. The latter was devised by taking into account three categories (low, medium and high use) based on the 33.33 and 66.66 percentiles in the T1 responses. Students exhibiting abusive use were considered to be those who gave scores in the upper third.

To analyze the program’s impact on the prevalence of aggression in cyberbullying and bullying, as well as sexting and the abusive use of the Internet and social networks, the percent variation in each of the groups (control and quasi-experimental) was calculated. This variation represents the difference between prevalence in T1 and T2 in relation to the value shown in T1. Such variation was calculated using the following formula: [(PrevalenceT2-PrevalenceT1)/ PrevalenceT1] × 100. In addition, a chi-square test, including involvement in cyber aggression, aggression, sexting and abusive use of the Internet and social networks, was used to compare the statistical significance of this variation in T1 and T2, respectively, by condition, control or experimental. The test’s significance would indicate an association in involvement between T1 and T2, that is, involvement has not substantially changed; its absence would indicate that the role has changed.

To achieve the second objective, those students identified as cyber aggressors in T1 were selected. Subsequently, two new quantitative variables for cyber aggression and aggression were calculated based on the means of the items that make up each dimension in order to analyze the variability in both phenomena. Two 2 x 2 repeated measures (2 times, T1 and T2, X 2 conditions, control and experimental) ANOVAs were used to compare changes in the intensity of cyber aggression and aggression, respectively. For the third objective, which was to analyze whether the prevalence of the studied risk factors, sexting and abusive use of the Internet and social networks, varied in the group of students self-identified as cyber aggressors in T1 by the condition, the percent variation for these factors in the aforementioned group of students was calculated.

Coding and data analysis were carried out using the SPSS program, version 21, except for the percent variation calculation which used Excel 2016.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of the “Asegúrate” Program on the prevalence of cyber aggression, sexting and the abusive use of the Internet and social networks

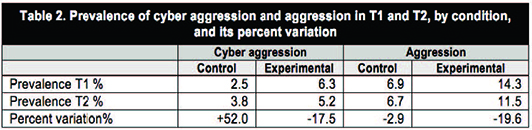

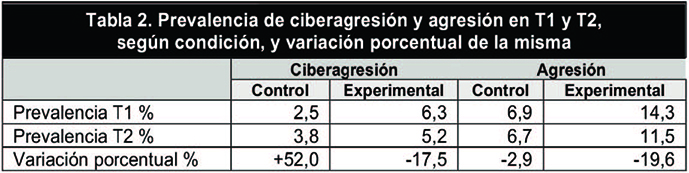

The results relative to the program’s impact on the prevalence of cyber aggression and aggression revealed the different percent variations in the control and experimental groups. Table 2 shows how cyber aggression involvement diminished by 17.5% in the quasi-experimental group and increased by 52% in the control group. Prevalence of bullying aggression diminished in both groups, but more so in the quasi-experimental group (19.6% vs. 2.9%).

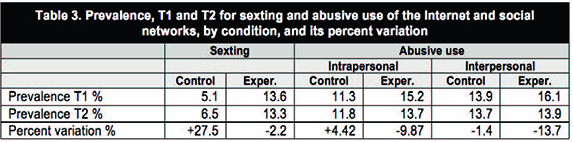

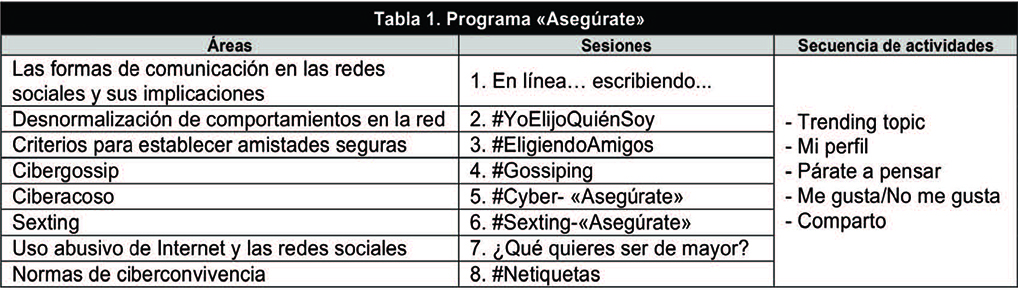

The chi-square test was significant in the control group, ?2 (1, 187)=24.028, p=.001, which means that there is an association between cyber aggression in T1 and T2, whereas the test was not significant in the quasi-experimental group, ?2 (1, 289)=1.198, p=.274. The results for aggression were similar: a significant association in the control group, ?2 (1, 187)=14.026, p=.001, and a non-significant one in the quasi-experimental group, ?2 (1, 290)=0.553, p=.481. Regarding the change in prevalence of the two risk factors, sexting, and abusive use, the results of the percent variation show changes in both groups, but in a different order (Table 3). Thus, the percent variation for sexting and the intrapersonal dimension for abusive use in the control group represents an increase; however, a decrease is observed in the quasi-experimental group for both cases. In terms of the interpersonal dimension for abusive use, a decrease is observed in both the control and quasi-experimental groups; although the magnitude in both groups varied, proving greater in the quasi-experimental group.

For sexting, the chi-square test was significant in the control group, ?2 (1, 187)=41.987, p= .001, and non-significant in the quasi-experimental group, ?2 (1, 280)= 3.345, p=.067, yielding the same outcome as intrapersonal abusive use (?2 control [1, 187])=63.703, p=.001, ?2 quasi-experimental [1, 269]=0.73, p=.787). For interpersonal abusive use, the association was significant in the control group, ?2 (1, 187)=45.120, p=.001, and bordered on significance in the quasi-experimental group, ?2 (1, 269)=3.937, p=.047.

3.2. Impact on the intensity of cyber aggression and aggression in cyber aggressors

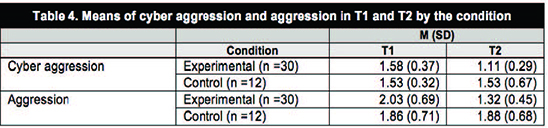

The ANOVA results for cyber aggression showed a significant intra-subject effect of time, F (1, 40)=7.108, p=.011, ?2p=.151, but not of condition, F (1, 40)=3.280, p=.078, ?2p=.076. However, these effects are qualified by the interaction between time and condition, F (1, 40)=6.959, p=.012, ?2p=.148. Regarding aggression, the results followed a similar pattern, a significant effect of time, F (1, 40)=9.034, p=.005, ?2p=.184; a lack of significance for condition, F (1, 40)=1.138, p=.292, ?2p=.028; and a significant interaction, F (1, 40)=9.990, p=.003, ?2p=.200.

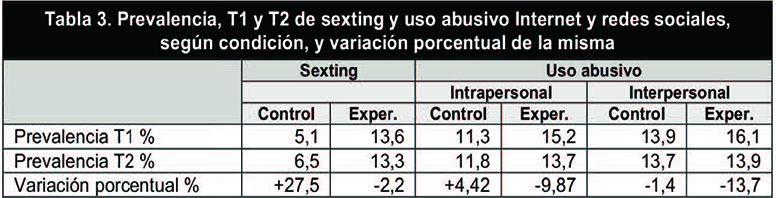

These data reveal a clear decline in cyber aggression and aggression associated with the intervention, as can be observed when comparing the means (Table 4).

3.3. Involvement of cyber aggressors in risk factors

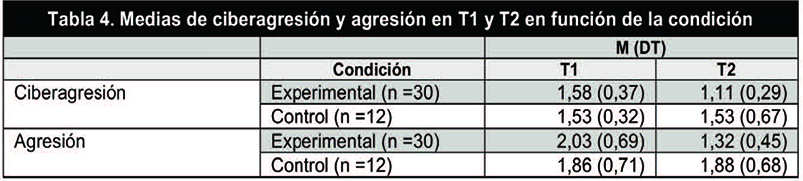

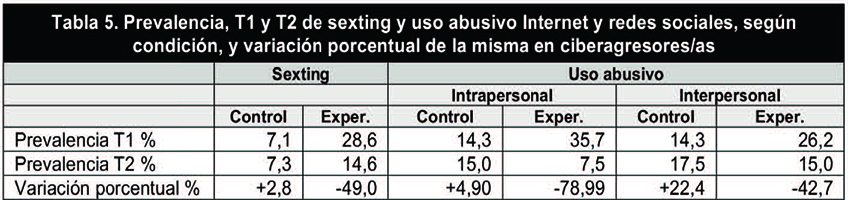

Taking into account those adolescents identified as cyber aggressors in T1, the percent variation in the prevalence of sexting and abusive use of the Internet and social networks in both groups, control and quasi-experimental, was analyzed (Table 5). The results reveal that direct sexting involvement decreased by almost half in the quasi-experimental group, whereas a slight increase was found in the control group. As for abusive use, an increase was observed in the control group, whereas a decrease in both the intrapersonal and interpersonal factors was found in the quasi-experimental group.

For sexting, the chi square was marginally significant in the control group and non-significant in the quasi-experimental group, ?2 control (1, 12)=3.704, p=.054; ?2 quasi-experimental (1, 29)=0.232, p=.630.

For abusive use, the associations were non-significant for group and the intrapersonal factor, ?2 control (1, 12)=1.333, p=.546; ?2 quasi-experimental (1, 28)=0.232, p=.630; and non-significant for the interpersonal factor, ?2 control (1, 12)=3.086, p=.079; ?2quasi-experimental (1, 28)=0.019, p=.891.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The majority of intervention programs tackling bullying and cyberbullying are effective at addressing victimization (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011), but they are scarcely effective at reducing aggressive behaviors. The aim of this study was to analyze the impact of the “Asegúrate” program on cyber aggression and aggression for the cited phenomena. In light of the results obtained, we can conclude that this program is effective at not only reducing the prevalence of cyber aggressions and aggressions, but it is also effective in reducing the involvement in other phenomena considered to be risk factors for cyberbullying: sexting and the abusive use of the Internet and social networks (Del Rey & al., 2016).

Specifically, the results corresponding to the first objective show that, without intervention, involvement in cyber aggression, sexting, and intrapersonal abusive use increases; however, it diminishes with intervention. This percent variation is especially notable in cyber aggression. This aspect is particularly noteworthy given that earlier studies report on how, as these phenomena hold over time, the potential harm for all those involved increases (Livingstone & Smith, 2014). Furthermore, in the case of bullying aggression and the abusive use of the Internet and social networks interpersonal factor, the analysis of the control group results shows that, unlike the previously mentioned phenomena, these tend to diminish over time. However, the comparative assessment demonstrates that the program accelerates this reduction, yielding a percent variation almost seven times greater in aggression and almost ten times greater in interpersonal abusive use in the quasi-experimental groups than in the control groups. A possible explanation for this diminishing aggression in bullying has to do with the phenomenon’s development, given that several studies have observed a decline with advancing age, continuing to fall after the second year of compulsory secondary education (Sastre, 2016). Nevertheless, the program’s impact highlights the importance of intervention to speed up this decline. The decrease found in the abusive use interpersonal factor is, to some extent, surprising, especially given that available data indicate that abusive use increases with advancing age, at least between 9 and 16 years of age (Casas, Ruiz-Olivares, & al., 2013). This aspect coincides with the increase observed in the intrapersonal factor corresponding to the control group. However, in this case, the decline observed in the interpersonal factor, coupled with the fact that intervention does not appear to alter involvement levels substantially, suggest the need for analysis into which of the program’s factors could be responsible for facilitating a more controlled and “less compulsive” use of the Internet and social networks as a way of escaping, but not as a way of interacting with others. Similarly, the fact that a trend shift is observed when the program is developed (in cyber aggression, in sexting and the abusive use intrapersonal factor) emphasizes the appropriateness of the methodology used. This demonstrates the important role that self-regulation plays as an inhibitor of aggression, as previously reported by other authors (Vazsonyi & al., 2012). Another key finding of the present study is that, although “anti-bullying” programs are used to prevent cyberbullying among students (Williford & al., 2013), certain programs geared towards preventing cyberbullying, such as those commented upon in the introduction (Del Rey, & al., 2012; Garaigordobil & Martínez-Valderrey, 2015) and “Asegúrate”, the program subject to study, are also used to prevent aggression in bullying situations.

In terms of the second objective, namely the decline in intensity of aggressive behaviors, the results once again confirm the effectiveness of the program, with significant differences between the control and quasi-experimental groups emerging. From this perspective, and given how difficult it is to change the aggressors’ conduct (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011), the results support the aforementioned effect of self-regulation whereby, not only does it reduce these behaviors in general, but also the students that exhibit them are able to reduce their intensity. What is more, the results demonstrate the transfer of this control from virtual environments (which this program primarily works in) to physical environments. A further explanation for the possible factors responsible for these results has to do with teacher involvement in program implementation. From this perspective, earlier studies show that one of the factors associated with aggression is students’ perceptions of teacher non-involvement (Casas & al., 2015). The fact that “Asegúrate” is a teacher-implemented program could change students’ perceptions in this respect.

Regarding the third and final objective, the results partially corroborate the program’s effect on risk factors in cyber-aggressors. Thus, whereas sexting involvement increases in non-intervened cyber aggressors, a decline by almost a half is observed in the quasi-experimental condition. Conversely, in the case of abusive use, the results do not allow us to confirm whether the program is responsible for the changes observed between the control and quasi-experimental groups. In any case, it is important to highlight the reduced number of students per group in this analysis as a study limitation. We can conclude that “Asegúrate”, besides being a program that reduces and occasionally prevents involvement in interpersonal aggressive behaviors, bullying, and cyberbullying, also reduces and prevents sexting involvement. This dual aspect is especially important given that previous meta-analyses on interventions aimed at reducing school-based aggressions have shown, in general terms, how these programs are effective at reducing levels of aggression when it is high, but not at preventing a potential increase in aggression (Wilson & Lipsey, 2007).

Taken together, the results endorse “Asegúrate” as a useful practice that could well be considered an evidence-based practice to reduce the cyberbullying and bullying phenomena, sexting and certain dimensions corresponding to the abusive use of the Internet and social networks. Given the evidence that the holding of these problems over time heightens their impact and effects, programs like the one presented here should be seen as essential tools in schools’ daily activities.

Lastly, it is important to note the limitations of this study and future lines of research opened up by the results. In addition to the problems inherent in the use of self-report measures, the short-term longitudinal design used represents a strength yet makes it difficult to control certain variables. Thus, there is no leveling between the quasi-experimental group and the control group in terms of the number of participants, schools, and students. Similarly, the control of outside variables, such as the schools’ participation in other activities covered in their co-existence plans, was not possible. Although this hinders the interpretation of the results, it gives them ecological validity, given that this represents the real day-to-day workings of our schools. As for the reality of the phenomena under study, the not very high number of students included in the cyber-aggression analyses, as well as their uneven distribution across the control groups (12) and the quasi-experimental groups (30), means that we should interpret these results with a degree of caution. Regarding future lines of research, we would need to determine whether a longer program would produce stronger or more longer-lasting effects, as reported in other studies. Similarly, we would need to continue investigating the matter to clearly identify which factors that help to prevent cyber aggression also help to prevent traditional aggression and vice-versa, as well as the common and differential associated risk factors, sexting and the abusive use of the Internet and social networks. From this perspective, a more detailed map of these factors would enable us to draw up intervention proposals with common features, based on different risks, and specific features, which are applicable to specific populations and in highly vulnerable developmental periods.

Funding Agency

This program was funded through the I+D project of the 2013-2016 State Plan of Excellence “Sexting, cyberbullying y riesgos emergentes en la red: claves para su comprensión y respuesta educativa (Sexting, cyberbullying and emerging online risks: keys for its understanding and an educational response)” (EDU2013-44627-P).

References

Álvarez-García, D., Barreiro-Collazo, A., & Núñez, J.C. (2017). Ciberagresiones entre adolescentes: prevalencia y diferencias de género. [Cyberaggression among adolescents: prevalence and gender differences]. Comunicar, 25(50), 89-97. https://doi.org/10.3916/C50-2017-08

Casas, J.A., Del Rey, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 580-587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.015

Casas, J.A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Del Rey, R. (2015). Bullying: The impact of teacher management and trait emotional intelligence. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 407-423. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12082

Casas, J.A., Ruiz-Olivares, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Validation of the Internet and Social Networking Experiences Questionnaire in Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 13(1), 40-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1697-2600(13)70006-1

Casey, B. J., Jones, R.M., & Hare, T.A. (2008). The Adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 111-126. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.010

Cerezo, F., & Rubio, F.J. (2017). Medidas relativas al acoso escolar y ciberacoso en la normativa autonómica española. Un estudio comparativo. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 20(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop/20.1.253391

Cerezo, F., Arnaiz, P., Giménez, A.M., & Maquilón, J.J. (2016). Conductas de ciberadicción y experiencias de cyberbullying entre adolescentes. Anales de Psicología, 32(3), 761-769. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.217461

Colás, P., González, T., & de-Pablos, J. (2013). Juventud y redes sociales: motivaciones y usos preferentes. [Young people and social networks: Motivations and preferred uses]. Comunicar, 20(40), 15-23. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-02-01

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., & Ortega, R. (2016). Impact of the ConRed program on different cyberbulling roles. Aggressive Behavior, 42(2), 123-135. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21608

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2012). El programa ConRed: una práctica basada en la evidencia. [The ConRed Program, an evidence-based practice]. Comunicar, 23(45), 129-138. https://doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-03-03

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., … Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.065

Del Rey, R., Elipe, P., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2012). Bullying y cyberbullying: Overlapping and predictive value of the co-ocurrence. Psicothema, 24(4), 608-613.

Gámez-Guadix, M., de Santisteban, P., & Resett, S. (2017). Sexting entre adolescentes españoles: Prevalencia y asociación con variables de personalidad. Psicothema, 29(1), 29-34. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.222

Garaigordobil, M. (2015). Ciberbullying en adolescentes y jóvenes del País Vasco: Cambios con la edad. Anales de Psicología, 31(3), 1069. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.3.179151

Garaigordobil, M., & Martínez-Valderrey, V. (2015). Efectos del Cyberprogram 2.0 en el bullying ‘cara-a-cara’, el cyberbullying y la empatía. Psicothema 27(1), 45-51. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.78

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J.W. (2008). Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behavior, 29(2), 129-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639620701457816

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J.W. (2012). School climate 2.0: Preventing cyberbullying and sexting one classroom at a time. School climate 2.0: Preventing cyberbullying and sexting one classroom at a time. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin Press.

Joseph, N. (2009). Metacognition Needed: Teaching middle and high school students to develop strategic learning skills. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 54(2), 99-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459880903217770

Klettke, B., Hallford, D.J., & Mellor, D.J. (2014). Sexting prevalence and correlates: A systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(1), 44-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.007

Korenis, P., & Billick, S.B. (2014). Forensic implications: Adolescent sexting and cyberbullying. Psychiatric Quarterly, 85(1), 97-101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-013-9277-z

Livingstone, S., & Smith, P.K. (2014). Annual research review: Harms experienced by child users of online and mobile technologies: The nature, prevalence and management of sexual and aggressive risks in the digital age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12197

Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Bullying in schools: the state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(1), 240-253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

Modecki, K. L., Barber, B.L., & Vernon, L. (2013). Mapping developmental precursors of cyber-Aggression: Trajectories of isk predict perpetration and victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(5), 651-661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9887-z

Nacimiento, L., Rosa, I., & Mora-Merchán, J.A. (2017). Valor predictivo de las habilidades metacognitivas en el afrontamiento en situaciones de bullying y cyberbullying. Informes Psicológicos, 17(2), 135-158. https://doi.org/10.18566/infpsic.v17n2a08

Ortega, R., Elipe, P., Mora-Merchán, J.A., Genta, M.L., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., & al. (2012). The emotional impact of bullying and cyberbullying on victims: a European cross-national study. Aggress. Behav. 38, 342-356. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21440

Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R., & Casas, J.A. (2016). Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 71-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.01.004

Powell, K.C.,& Cody, J.K. (2009). Cognitive and social constructivism: developing tools for and effective classroom. Education, 130(2), 241-250.

Prodócimo, E., Cerezo, F., & Arense, J.J. (2014). Acoso escolar: variables sociofamiliares como factores de riesgo o de protección. Behavioral Psychology, 22(2), 345-362.

Rimal, R.N., & Lapinski, M.K. (2015). A re-explication of social norms, ten years later. Communication Theory, 25(4), 393-409. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12080

Roncero, D., Andreu, J., & Peña, M.E. (2016). Procesos cognitivos distorsionados en la conducta agresiva y antisocial en adolescentes Distorted cognitive processes in aggressive and antisocial behavior in adolescents. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 26(1), 88-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apj.2016.04.002

Sastre, A. (2016). Yo a eso no juego. Madrid: Save the Children. https://bit.ly/1oDaq9U

Ttofi, M.M., & Farrington, D.P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 27-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1

Van-Royen, K., Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., & Adam, P. (2017). ‘Thinking before posting?’ Reducing cyber harassment on social networking sites through a reflective message. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 345-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.040

Vannucci, M., Nocentini, A., Mazzoni, G., & Menesini, E. (2012). Recalling unpresented hostile words: False memories predictors of traditional and cyberbullying. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(2), 182-194. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2011.646459

Vazsonyi, A. T., Machackova, H., Sevcikova, A., Smahel, D., & Cerna, A. (2012). Cyberbullying in context: Direct and indirect effects by low self-control across 25 European countries. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(2), 210-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2011.644919

Waasdorp, T.E., & Bradshaw, C.P. (2015). The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(5), 483-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.002

Williford, A., Elledge, L.C., Boulton, A.J., DePaolis, K.J., Little, T.D., & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Effects of the KiVa Antibullying program on cyberbullying and cybervictimization frequency among Finnish youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(6), 820-833. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.787623

Wilson, S.J., & Lipsey, M.W. (2007). School-based interventions for aggressive and disruptive behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33(2), S130-S143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.011

Ybarra, M.L., & Mitchell, K.J. (2014). Sexting and its relation to sexual activity and sexual risk behavior in a national survey of adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(6), 757-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.012

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

La intervención contra el ciberacoso entre escolares y otros riesgos asociados al uso inapropiado de las TIC y las redes sociales, es una importante demanda social. El programa «Asegúrate» pretende facilitar la labor docente en dicha intervención. El presente trabajo da cuenta del impacto de este programa entre quienes han mostrado ser menos sensibles en otros programas: los ciberagresores. Concretamente, se analiza su impacto en la prevalencia de agresión en ciberacoso y acoso escolar, así como en sexting y uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales. La evaluación del programa se desarrolló con un total de 479 estudiantes (54,9% chicas) de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (edad M=13,83. DT=1,40) mediante una metodología cuasi-experimental, con dos mediciones a lo largo del tiempo. Los instrumentos utilizados fueron el «European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire», el «European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire», el «Cuestionario de Experiencias Relacionadas con Internet» y dos ítems sobre implicación en sexting. Los resultados muestran que, en ausencia de intervención, la implicación en ciberagresión, sexting y la dimensión intrapersonal del uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales aumenta mientras que, con intervención, dichas implicaciones disminuyen. Asimismo, se evidencia una disminución significativa de la intensidad de la agresión y ciberagresión en ciberagresores. Por tanto, se puede afirmar que el programa resulta efectivo tanto para disminuir la prevalencia de agresiones y ciberagresiones como la implicación en otros fenómenos considerados factores de riesgo del ciberacoso.

1. Introducción

1.1. Ciberacoso entre escolares y sus riesgos

El ciberacoso entre escolares es un fenómeno emergente de agresión repetida surgido tras la expansión y generalización del uso de los medios digitales para la comunicación y la vida social (Hinduja & Patchin, 2008). Para su estudio, muchos investigadores han tomado de referencia su homólogo en el contexto físico (Garaigordobil, 2015), el acoso escolar, que cuenta con una larga trayectoria científica (Prodócimo, Cerezo, & Arense, 2014). De hecho, a pesar de sus diferencias, principalmente debidas a las existentes entre los contextos en los que acontecen (Vannucci, Nocentini, Mazzoni, & Menesini, 2012), hoy sabemos que existe una alta co-implicación entre ambos (Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015). Los estudios realizados con muestras españolas señalan ciertas divergencias en la prevalencia. En el último estudio realizado con muestra representativa de jóvenes españoles (Sastre, 2016), la implicación resultó del 10,2% (3,3% ciberagresión y 6,9% cibervictimización), cifra superior al 7,7% que hallaban Cerezo, Arnaiz, Giménez y Maquilón (2016). Estos datos se dispersan al atender las diversas formas, disminuyendo en las más graves (Álvarez-García, Barreiro-Collazo, & Núñez, 2017).

Los esfuerzos por comprender estas conductas van mostrando factores de riesgo que facilitan las ciberagresiones (Modecki, Barber, & Vernon, 2013). Entre ellos, parecen tener gran relevancia para la intervención psicoeducativa el uso abusivo de las redes sociales y el sexting (Del Rey, Casas, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2012). En relación con el uso abusivo, los «smartphones» han facilitado un aumento generalizado del tiempo de conexión, particularmente entre los más jóvenes (Colás, González, & de-Pablos, 2013). A pesar de ello, los implicados en ciberacoso entre escolares, particularmente los ciberagresores, siguen estando significativamente más tiempo conectados que los no implicados (Hinduja & Patchin, 2008). Por su parte, el sexting, entendido como el envío y recepción de mensajes, imágenes o vídeos de carácter erótico sexual mediante un dispositivo tecnológico, sobre todo teléfonos móviles (Klettke, Hallford, & Mellor, 2014), merece especial atención tanto por ser un factor de riesgo del ciberacoso (Livingstone & Smith, 2014), como por el impacto que tiene en sí mismo (Korenis & Billick, 2014). Además, la implicación en este fenómeno está aumentando entre la adolescencia española (Gámez-Guadix, de Santisteban, & Resett, 2017).

1.2. Intervenir contra la ciberagresión y sus riesgos

La necesidad de intervenir ante el ciberacoso entre escolares está hoy fuera de toda duda dadas las cifras y consecuencias del fenómeno (Ortega & al., 2012). Los resultados empíricos ponen de manifiesto que los programas contra el acoso escolar son parcialmente efectivos contra el ciberacoso (Williford & al., 2013). No obstante, también existe evidencia de la necesidad de incorporar contenidos específicos referidos a los entornos virtuales y redes sociales (Del Rey & al., 2012) y al sexting (Hinduja & Patchin, 2012).

En España, se han dado pasos, progresivamente, en la atención al ciberacoso entre escolares. Las primeras medidas públicas han consistido en adaptar los protocolos de acoso escolar y los proyectos de convivencia al ciberacoso (Cerezo & Rubio, 2017). Está en marcha el Plan Estratégico de Convivencia Escolar 2016, del Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, donde se priorizan la prevención de la violencia, la educación en el uso de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación y la formación del profesorado. En esta materia, se ha demostrado que el sentimiento de competencia del profesorado es clave para el descenso de los fenómenos de acoso y ciberacoso (Casas, Ortega-Ruiz, & Del Rey, 2015; Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017).

También se han desarrollado y evaluado empíricamente programas contra el ciberacoso entre escolares como Cyberprogram 2.0 (Garaigordobil & Martínez-Valderrey, 2015) y ConRed (Del Rey & al., 2012), entre otros, que han mostrado ser eficaces para disminuir tanto la cibervictimización como la ciberagresión, además del acoso escolar y otros riesgos. El ConRed ha mostrado, incluso, su impacto entre ciberagresores (Del Rey, Casas, & Ortega, 2016). No obstante, aún es poco lo que se sabe del impacto en la prevalencia de la ciberagresión, uno de los objetivos más difíciles de alcanzar en las intervenciones sobre acoso escolar (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011).

1.3. El programa «Asegúrate»

El programa «Asegúrate» nace con intención de facilitar la labor docente en la intervención contra el ciberacoso entre escolares y sus riesgos, y potenciar el sentimiento de competencia del profesorado en esta materia. Dicho programa se asienta sobre tres pilares esenciales:

a) La teoría del comportamiento social normativo (Rimal & Lapinski, 2015). Esta resalta cómo el comportamiento social se ve influenciado de forma significativa por las normas del entorno, modulando la conducta hasta adoptar los patrones y convenciones externos y evitando discrepar con ellos. Defiende que nuestra conducta estaría impulsada por lo que se percibe como socialmente aceptado, normal o legal (Del- Rey & al., 2012). Así, las y los adolescentes se comportan con sus iguales en las redes sociales (también en las relaciones cara a cara) de acuerdo a cómo perciben las normas de relación en los entornos online, apareciendo las malas relaciones como una suerte de mimetización con el contexto guiada por los tres mecanismos normativos: la identidad de grupo, las expectativas y las normas legales reconocidas. Reconocer estas claves y devolverlas en positivo al alumnado sería un elemento esencial para una intervención exitosa. «Asegúrate» parte de estos procesos para diseñar la intervención: por un lado, presentando modelos de identificación positiva con el grupo, destacando cómo algunos comportamientos no suponen mayor integración con los iguales; por otra parte, analizando las expectativas del alumnado ante situaciones cotidianas y oponiéndolas a los efectos reales que tienen las malas relaciones y las situaciones de acoso en la red; y finalmente, analizando las normas existentes en las redes y valorando junto con el alumnado el impacto de las mismas.

b) Las habilidades de autorregulación. La inclusión de elementos reflexivos, dirigidos a potenciar las habilidades metacognitivas en programas de naturaleza psicoeducativa, se lleva realizando desde hace tiempo con éxito (Joseph, 2009). Se ha identificado que las personas con menor autorregulación tienen mayor probabilidad de verse implicadas en conductas de agresión, así como menor capacidad para valorar las consecuencias de sus acciones en los demás (Roncero, Andreu, & Peña, 2016). En el caso concreto del ciberacoso entre escolares, también se ha apreciado una relación entre baja autorregulación e implicación (Vazsonyi, Machackova, Sevcikova, Smahel, & Cerna, 2012) y entre menor dominio de habilidades metacognitivas y uso de estrategias de afrontamiento no productivas (Nacimiento, Rosa, & Mora-Merchán, 2017). De ahí que la inclusión de elementos que faciliten la reflexión sobre las propias acciones, resulte necesaria, en especial en la adolescencia, período evolutivo marcado por más bajo autocontrol y mayor impulsividad (Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008). Elementos especialmente relevantes en la comunicación online, dada la percepción del anonimato, escasas consecuencias e invisibilidad, que pueden promover un menor control inhibitorio y, por ende, un aumento de la conducta ciberagresiva (Van-Royen, Poels, Vandebosch, & Adam, 2017).

c) Las ideas/creencias de las y los jóvenes. Siguiendo los principios de las metodologías constructivistas (p. ej.: Powell & Cody, 2009), la secuencia de actividades (Tabla 1) parte de identificar las ideas previas sobre escenarios virtuales, especialmente redes sociales. Seguidamente se promueve el análisis del propio comportamiento en esos escenarios. Posteriormente, se potencia la reflexión sobre las razones que justifican dichos comportamientos. Tras ello, se analizan las potenciales consecuencias de las conductas expuestas, tanto en quienes las emiten, como en quienes las reciben. Finalmente, se concluye con una actividad para la generalización y transferencia de los logros a otros contextos de relación. Todas estas tareas siguen un planteamiento reflexivo, necesario para la progresiva reformulación de las creencias y expectativas del alumnado. Esta secuencia fija de actividades en todas las sesiones del programa facilita que el profesorado, que es quien aplica el programa, pueda elaborar unidades de trabajo propias siguiendo una lógica común que permita la adaptación a las características de su alumnado.

1.4. Finalidad y objetivos

Dada la novedad del programa y la necesidad de conocer su efectividad, particularmente entre quienes han mostrado ser menos sensibles en otros programas, el objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar el impacto del «Asegúrate» en la agresión en ciberacoso y acoso entre escolares, así como en dos de los factores de riesgo asociados, sexting y uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales. Concretamente, se pretendía conocer el impacto del programa en relación a tres objetivos específicos: a) en la prevalencia de la agresión en ciberacoso y acoso entre escolares, en sexting y en uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales; b) en la intensidad de las ciberagresiones y agresiones; y c) en la implicación de ciberagresores en los factores de riesgo considerados: sexting y uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales.

2. Material y métodos

2.1. Participantes

Han participado 479 estudiantes con un rango de edad de 12 a 18 años (54,9% chicas; edad M=13,83, DT=1,40) procedentes de siete centros educativos de Andalucía (España). Entre ellos, 292 pertenecen a cinco centros del grupo cuasi-experimental (57,4% chicas; edad M=13,84, DT=1,42) y 187 a dos del grupo control (51,1% chicas; edad M=13,84, DT=1,35).

2.2. Instrumentos

Para valorar la ciberagresión, se utilizó la subescala de agresión del «European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire» (ECIPQ) (Del Rey & al., 2015). Dicha escala está compuesta por 11 ítems que evalúan la frecuencia de ciberagresión, en los últimos dos meses, con respuestas en formato Likert (0=No; 1=Sí, 1 vez o 2 veces; 2=Sí, 1 o 2 veces al mes; 3=Sí, alrededor de 1 vez por semana; 4=Sí, más de una vez por semana), p. ej., «He insultado a alguien por las redes sociales o WhatsApp». La fiabilidad de esta subescala en el presente estudio fue a=,72.

Para evaluar la agresión en el acoso entre escolares, se utilizó la subescala de agresión del «European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire» (EBIPQ) (Ortega-Ruiz, Del Rey, & Casas, 2016). Está compuesta por siete ítems tipo Likert y evalúa la frecuencia de agresión con las mismas opciones de respuesta que la escala anterior; p. ej., «He insultado y he dicho palabras ofensivas a alguien». La fiabilidad de esta escala fue a=.72.

Para evaluar la implicación en sexting, siguiendo el método usado en otras investigaciones (p. ej., Ybarra & Mitchell, 2014), se utilizaron dos ítems ante los cuales el alumnado tenía que mostrar su acuerdo en una escala tipo Likert de siete opciones (0=Nada de acuerdo a 6=Totalmente de acuerdo). Las afirmaciones fueron: «He enviado vídeos, imágenes o mensajes de carácter erótico-sexual a mi chico/a» y «He recibido videos, imágenes o mensajes de carácter erótico sexual de mi chico/a».

Para evaluar el uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales se utilizó el «Cuestionario de Experiencias Relacionadas con Internet» (CERI) (Casas, Ruiz-Olivares, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2013). Está compuesto por 10 ítems tipo Likert con cuatro opciones (1=Nunca; 2=Casi nunca; 3=Frecuentemente y 4=Mucho) que miden la dimensión intrapersonal (p. ej., «Cuando tienes problemas, ¿conectarte a las redes sociales o hablar por WhatsApp te ayuda a evadirte de ellos?») e interpersonal de dicho uso (p. ej., «¿Te resulta más fácil o cómodo relacionarte con la gente través de una red social o de WhatsApp que en persona?»). Los índices de fiabilidad en este estudio fueron a inter=.70, a intra=.79, a total=.86.

2.3. Procedimiento

El muestreo realizado fue incidental por accesibilidad. A través de una llamada telefónica se contactó con centros educativos para solicitar su colaboración. Aquellos que accedieron fueron contactados para establecer una cita y acordar tanto el cronograma como los cursos que formarían parte del estudio. Los cuestionarios fueron administrados por personal en formación, entrenado para ello, durante el horario de clase, previo acuerdo con el profesorado. Antes de la administración de la prueba se enfatizó el carácter voluntario de la participación en el estudio, el anonimato y confidencialidad de los datos y la importancia de la sinceridad en las respuestas.

Tras la primera recogida, tiempo 1 (T1 en adelante) en cinco de los centros se llevó a cabo el programa (grupos cuasi-experimentales) y en dos no (grupos control). El compromiso de los centros cuasi-experimentales fue implementar, como mínimo, cuatro de las unidades didácticas que componían el programa (a elección propia). Tras finalizar la intervención en los centros cuasi-experimentales, al menos tres meses después del inicio de la misma, se volvieron a administrar los cuestionarios en los siete centros, tiempo 2 (T2). A los centros que no participaron en la intervención se les ofreció la posibilidad de desarrollar esta una vez finalizado el estudio.

La investigación se desarrolló de acuerdo a los estándares éticos de la Asociación de Padres y Madres, y fue aprobada por el Comité Coordinador de Ética de la Investigación Biomédica de Andalucía, que sigue las directrices de la Conferencia Internacional de la Buena Práctica Clínica. El proyecto y la batería de instrumentos a utilizar se presentaron y explicaron a la dirección del Centro, quienes lo valoraron positivamente. Esta lo presentó al Consejo Escolar, como parte de su Proyecto de Convivencia y del Plan de Mejora del Centro Educativo quien otorgó el consentimiento informado para participar en el mismo.

2.4. Análisis de datos

Con el fin de conseguir los objetivos propuestos, en primer lugar, se crearon cuatro variables dicotómicas. Dos relativas a la implicación en agresión de acoso y ciberacoso entre escolares, siguiendo los criterios propuestos por los autores de las escalas utilizadas (Del Rey & al., 2015): se consideró alumnado agresor a quienes afirmaron haber agredido una o dos veces al mes, o con mayor frecuencia en cualquiera de las conductas que se presentan para acoso o ciberacoso, respectivamente. En relación al sexting se consideraron activos quienes contestaron positivamente, al menos, a uno de los dos ítems directos (He enviado y he recibido vídeos, imágenes o mensajes de carácter erótico-sexual a mi chico/a). Para crear la variable uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales, se utilizaron las propias puntuaciones del alumnado elaborando una variable con tres categorías (uso bajo, medio y alto) a partir de los percentiles 33,33 y 66,66 en las respuestas de T1. Se consideró alumnado con uso abusivo quienes mostraron puntuaciones pertenecientes al tercio superior.

Para analizar el impacto del programa en la prevalencia de la agresión en ciberacoso y acoso escolar, de sexting y de uso abusivo de Internet, se calculó la variación porcentual en cada uno de los grupos (control y cuasi-experimental). Esta variación representa la diferencia entre la prevalencia en T1 y T2 en relación al valor mostrado en T1. Dicha variación se calculó con la siguiente fórmula: [(PrevalenciaT2-PrevalenciaT1)/ PrevalenciaT1] × 100. Adicionalmente, con objeto de contrastar la significación estadística de esta variación, se realizó una prueba Chi cuadrado, incluyendo la implicación en ciberagresión, agresión, sexting y uso abusivo de Internet, respectivamente, en T1 y T2, en función de la condición, control o experimental. La significación de esta prueba indicaría que existe asociación en la implicación entre T1 y T2, es decir, que la implicación no se ha alterado sustancialmente; su ausencia indicaría que ha variado el rol.

Para conseguir el segundo objetivo, se seleccionó al alumnado identificado como ciberagresor en T1. Posteriormente, se calcularon dos nuevas variables cuantitativas de ciberagresión y agresión a partir de las medias de los ítems que componen cada dimensión para poder analizar la variabilidad en los fenómenos. Se utilizaron dos ANOVAS 2 x 2 de medidas repetidas (2 tiempos, T1 y T2, X 2 condiciones, control y experimental) para comparar el cambio en intensidad de ciberagresión y agresión, respectivamente. Para analizar si la prevalencia de los factores de riesgo estudiados, sexting y uso abusivo de Internet, variaba en el grupo de alumnado autoidentificado como ciberagresor en T1, en función de la condición, tercer objetivo, se calculó la variación porcentual en dichos factores entre el citado grupo de alumnos/as.

La codificación y análisis de los datos se ha realizado con el programa SPSS, ver. 21, salvo para el cálculo de la variación porcentual que se utilizó Excel 2016.

3. Resultados

3.1. Impacto del programa «Asegúrate» en la prevalencia de ciberagresión, sexting y uso abusivo de Internet

Los resultados relativos al impacto del programa en la prevalencia de ciberagresión y agresión mostraron variaciones porcentuales diferentes en el grupo control y cuasi-experimental. En la Tabla 2 se muestra cómo la implicación en ciberagresión disminuyó en el grupo cuasi-experimental un 17,5%, mientras que en el grupo control aumentó un 52%. La prevalencia de la agresión de acoso disminuyó en ambos grupos, pero más en el grupo cuasi-experimental (19,6% vs 2,9%).

La prueba Chi cuadrado resultó significativa en el grupo control, ?2 (1, 187)=24,028, p=,001, lo que implica que existe una asociación entre ciberagresión en T1 y T2, mientras que no resultó significativa en el grupo cuasi-experimental, ?2 (1, 289)=1,198, p=,274. En agresión, los resultados fueron similares: asociación significativa en grupo control ?2 (1, 187)=14,026, p=,001, y no significativa en cuasi-experimental, ?2 (1, 290)=0,553, p=,481. En cuanto al cambio en la prevalencia de los factores de riesgo, sexting y uso abusivo, los resultados de la variación porcentual muestran cambios en ambos grupos, pero de diferente orden (Tabla 3). Así, la variación porcentual en el grupo control de sexting y dimensión intrapersonal del uso abusivo supone un aumento, mientras que en el cuasi-experimental hay una disminución en ambos casos. En la dimensión interpersonal del uso abusivo, si bien tanto en grupo control como cuasi-experimental, hay una disminución, la magnitud de ambos grupos varía siendo mayor en el cuasi-experimental.

En sexting, la prueba Chi resultó significativa en el grupo control, ?2 (1,187)=41,987, p=,001, y no en el cuasi-experimental, ?2 (1, 280)=3,345, p=,067, al igual que en uso abusivo intrapersonal (?2 control [1, 187])=63,703, p=,001, ?2 cuasi-experimental [1, 269]=0,73, p=,787). En uso abusivo interpersonal la asociación fue significativa en el grupo control, ?2 (1, 187)=45,120, p=,001, y rozando el límite de la significación en el cuasi-experimental, ?2 (1, 269)=3,937, p=,047.

3.2. Impacto en la intensidad de ciberagresión y agresión en ciberagresores

Los resultados del ANOVA, en relación a la ciberagresión, mostraron un efecto significativo a nivel intra sujeto del tiempo, F (1, 40)=7,108, p=,011, ?2p=,151, pero no de la condición, F (1, 40)=3,280, p=,078, ?2p=,076. Sin embargo, estos efectos están matizados por la interacción entre tiempo y condición, F (1, 40)=6,959, p=,012, ?2p=,148. En relación a la agresión, los resultados siguieron un patrón similar: un efecto significativo del tiempo, F (1, 40)= 9,034, p=,005, ?2p =,184; una ausencia de significación de la condición, F (1, 40)=1,138, p=,292, ?2p=,028; y una interacción significativa, F (1, 40)=9,990, p=,003, ?2p=,200.

Estos datos ponen de manifiesto una clara disminución de ciberagresión y agresión asociada a la intervención, tal y como puede observarse al comparar las medias (Tabla 4).

3.3. Implicación de ciberagresores en factores de riesgo

Asimismo, entre aquellos jóvenes identificados como ciberagresores en T1, se analizó la variación porcentual en la prevalencia del sexting y uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales en ambos grupos, control y cuasi-experimental (Tabla 5). Los resultados muestran que la implicación directa en sexting disminuye casi la mitad en el grupo cuasi-experimental, mientras que en el de control hay un ligero aumento. En relación al uso abusivo, mientras que en el grupo control hay un aumento, en el cuasi-experimental hay una disminución, tanto en el factor intrapersonal como interpersonal.

En sexting, la Chi cuadrado resultó marginalmente significativa en el grupo control y no significativa en el cuasi-experimental, ?2 control (1, 12= 3,704, p=,054; ?2 cuasi-experimental (1, 29 =0,232, p=,630.

En uso abusivo no resultaron significativas las asociaciones de ningún grupo ni en el factor intrapersonal, ?2 control (1, 12)=1,333, p=,546; ?2 cuasi-experimental (1, 28)=0,232, p=,630; ni en el interpersonal, ?2 control (1, 12)=3,086, p=,079; ?2 cuasi-experimental (1, 28)=0,019, p=,891.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

La mayor parte de los programas de intervención en acoso y ciberacoso escolar son efectivos en la victimización (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011), pero escasamente lo son en reducción de la conducta agresiva. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar el impacto del programa «Asegúrate» en ciberagresión y agresión en los fenómenos citados. A la luz de los resultados, podemos concluir que dicho programa resulta efectivo tanto para disminuir la prevalencia de las ciberagresiones y agresiones como la implicación en otros fenómenos considerados factores de riesgo del ciberacoso: sexting y uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales (Del Rey & al., 2016).

En concreto, en relación al primer objetivo, los resultados permiten constatar que sin intervención la implicación de ciberagresión, sexting y uso abusivo intrapersonal aumenta, mientras que con la intervención disminuye, siendo esta variación porcentual especialmente notable en ciberagresión. Este aspecto es especialmente reseñable, ya que estudios previos señalan cómo a medida que estos fenómenos se mantienen en el tiempo aumenta el daño potencial para todos los implicados (Livingstone & Smith, 2014). Por otra parte, tanto en relación a la agresión en acoso escolar como al factor interpersonal del uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales, el análisis de los resultados de los grupos control muestra que, a diferencia de los fenómenos previos, estos tienden a disminuir a medida que pasa el tiempo. No obstante, la comparativa demuestra que el programa acelera esta disminución siendo la variación porcentual casi siete veces mayor en agresión y casi diez veces mayor en uso abusivo interpersonal en los grupos cuasi-experimentales que en los de control. Una posible explicación de la disminución de la agresión en acoso tiene que ver con el propio desarrollo del fenómeno, ya que diversos estudios señalan un decrecimiento en el mismo a medida que aumenta la edad, disminuyendo tras el segundo ciclo de Secundaria (Sastre, 2016). No obstante, el impacto del programa resalta la importancia de intervenir para acelerar este decrecimiento. La disminución encontrada en el factor interpersonal del uso abusivo resulta, en cierta medida, sorprendente, ya que los datos disponibles sugieren un aumento en uso abusivo a medida que se incrementa la edad, al menos entre los 9 y los 16 años (Casas & al., 2013), aspecto este que concuerda con el aumento encontrado en el factor intrapersonal en el grupo control. Sin embargo, el decrecimiento observado en el factor interpersonal, así como el hecho de que la intervención no parezca variar de forma sustancial la implicación, en este caso, plantea la necesidad de analizar qué factores del programa podrían ser los responsables de facilitar un uso más controlado y «menos compulsivo» de Internet y las redes sociales como forma de evasión, pero no como forma de interacción con otros. De igual modo, el hecho de que tanto en ciberagresión como en sexting y factor intrapersonal del uso abusivo haya un cambio de tendencia cuando se interviene enfatiza la pertinencia de la metodología utilizada evidenciando la importancia del elemento de autorregulación como inhibidor de la agresión ya señalado por otros autores (Vazsonyi & al., 2012). Otro hallazgo clave del presente estudio es que, si bien los programas «anti-bullying» sirven para prevenir el ciberacoso entre escolares (Williford & al., 2013), también ciertos programas para prevenir ciberacoso, como los comentados en la introducción (Del Rey & al., 2012; Garaigordobil & Martínez-Valderrey, 2015) y «Asegúrate», programa analizado, sirven para prevenir la agresión en situaciones de acoso escolar.

En relación al segundo objetivo, la disminución de la intensidad de las agresiones, los resultados nuevamente avalan la eficacia del programa apareciendo diferencias significativas entre el grupo control y el cuasi-experimental. En este sentido y dada la dificultad para modificar la conducta de los agresores (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011), los resultados avalan el efecto de autorregulación previamente comentado, haciendo que no solo disminuyan estas conductas en general, sino que el alumnado que las emite reduzca la intensidad de las mismas. Además, estos resultados, ponen de manifiesto la transferencia de este control desde contextos virtuales –que son los que principalmente trabaja el programa– a contextos físicos. Una explicación adicional sobre los posibles factores responsables de estos resultados tiene que ver con la implicación del profesorado en la implementación del programa. En este sentido, estudios previos muestran que uno de los factores asociados con la agresión es la percepción, por parte del alumnado, de no implicación del profesorado (Casas & al., 2015). El hecho de que «Asegúrate» sea implementado por el profesorado podría cambiar la percepción del alumnado a este respecto.

En cuanto al tercer objetivo, los resultados avalan, parcialmente, el efecto del programa en factores de riesgo en ciberagresores. Así, mientras que la implicación en sexting se incrementa en los ciberagresores sin intervención, en el grupo cuasi-experimental se observa una disminución casi a la mitad. En cambio, en el caso del uso abusivo, los resultados no nos permiten afirmar que el programa sea el responsable de los cambios observados entre grupo control y cuasi-experimental. En cualquier caso, es importante señalar como limitación el reducido número de alumnado por grupo en este análisis. Podemos concluir que «Asegúrate» además de ser un programa que reduce y, en ocasiones, revierte la implicación en agresiones interpersonales, acoso y ciberacoso entre escolares, reduce y previene la implicación en sexting. Esta doble vertiente es especialmente importante, ya que meta-análisis previos sobre intervenciones para reducir las agresiones en la escuela han evidenciado que, generalmente, estos programas son efectivos para reducir niveles de agresión cuando ésta es alta pero no para prevenir el incremento potencial en agresión (Wilson & Lipsey, 2007).

Tomados conjuntamente, los resultados avalan «Asegúrate» como una práctica útil que bien podría ser considerada una práctica basada en la evidencia para disminuir los fenómenos de ciberacoso y acoso escolar, así como sexting y ciertas dimensiones del uso abusivo de Internet. Dado que existen evidencias de que el mantenimiento en el tiempo de estos problemas intensifica su impacto y sus efectos, programas como el que aquí presentamos deberían ser herramientas ineludibles en el desarrollo cotidiano de los centros escolares.

Por último, mencionar las limitaciones de este estudio y las líneas futuras de investigación que los presentes resultados dejan abiertas. Además de los problemas inherentes al uso de instrumentos de autoinforme, el diseño utilizado, longitudinal a corto-plazo, supone, por una parte, una fortaleza, pero por otra, hace difícil el control de ciertas variables. Así, no existe igualación entre el grupo cuasi-experimental y el control en cuanto a número de participantes, centros y alumnado. De igual modo, el control de variables extrañas, tales como la participación de los centros escolares en otras actividades que formen parte de su plan de Convivencia, no resulta posible. En cualquier caso, si bien esto dificulta la interpretación de los resultados, aporta validez ecológica a los mismos, ya que este es el día a día real de nuestros centros educativos. Por último, y en relación con la realidad de los fenómenos estudiados, el no muy elevado número de alumnado incluido en los análisis de ciberagresión, así como su desigual distribución entre grupo control, 12, y cuasi-experimental, 30, hace que debamos interpretar los resultados referidos a este grupo con cierta cautela. En cuanto a líneas futuras, resulta necesario constatar si, tal y como se ha evidenciado en otros estudios, un programa más largo produciría efectos más potentes o más duraderos. De igual modo, sería necesario seguir indagando para delimitar de forma clara cuáles de los factores que ayudan a prevenir la ciberagresión ayudan también a prevenir la agresión directa y viceversa, así como factores comunes y diferenciales en los riesgos analizados, sexting y uso abusivo de Internet y redes sociales. En este sentido, un mapa más detallado de estos factores permitiría articular propuestas de intervención con elementos comunes, que estén a la base de diversos riesgos y que sean aplicables a poblaciones específicas o en momentos evolutivos especialmente vulnerables.

Apoyos

Este programa ha sido subvencionado por el proyecto I+D del Plan Estatal 2013-2016 Excelencia «Sexting, ciberbullying y riesgos emergentes en la red: claves para su comprensión y respuesta educativa» (EDU2013-44627-P).

Referencias

Álvarez-García, D., Barreiro-Collazo, A., & Núñez, J.C. (2017). Ciberagresiones entre adolescentes: prevalencia y diferencias de género. [Cyberaggression among adolescents: prevalence and gender differences]. Comunicar, 25(50), 89-97. https://doi.org/10.3916/C50-2017-08

Casas, J.A., Del Rey, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 580-587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.015

Casas, J.A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Del Rey, R. (2015). Bullying: The impact of teacher management and trait emotional intelligence. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 407-423. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12082

Casas, J.A., Ruiz-Olivares, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Validation of the Internet and Social Networking Experiences Questionnaire in Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 13(1), 40-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1697-2600(13)70006-1

Casey, B. J., Jones, R.M., & Hare, T.A. (2008). The Adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 111-126. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.010

Cerezo, F., & Rubio, F.J. (2017). Medidas relativas al acoso escolar y ciberacoso en la normativa autonómica española. Un estudio comparativo. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 20(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop/20.1.253391

Cerezo, F., Arnaiz, P., Giménez, A.M., & Maquilón, J.J. (2016). Conductas de ciberadicción y experiencias de cyberbullying entre adolescentes. Anales de Psicología, 32(3), 761-769. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.217461

Colás, P., González, T., & de-Pablos, J. (2013). Juventud y redes sociales: motivaciones y usos preferentes. [Young people and social networks: Motivations and preferred uses]. Comunicar, 20(40), 15-23. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-02-01

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., & Ortega, R. (2016). Impact of the ConRed program on different cyberbulling roles. Aggressive Behavior, 42(2), 123-135. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21608

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2012). El programa ConRed: una práctica basada en la evidencia. [The ConRed Program, an evidence-based practice]. Comunicar, 23(45), 129-138. https://doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-03-03

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., … Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.065

Del Rey, R., Elipe, P., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2012). Bullying y cyberbullying: Overlapping and predictive value of the co-ocurrence. Psicothema, 24(4), 608-613.

Gámez-Guadix, M., de Santisteban, P., & Resett, S. (2017). Sexting entre adolescentes españoles: Prevalencia y asociación con variables de personalidad. Psicothema, 29(1), 29-34. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.222

Garaigordobil, M. (2015). Ciberbullying en adolescentes y jóvenes del País Vasco: Cambios con la edad. Anales de Psicología, 31(3), 1069. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.3.179151

Garaigordobil, M., & Martínez-Valderrey, V. (2015). Efectos del Cyberprogram 2.0 en el bullying ‘cara-a-cara’, el cyberbullying y la empatía. Psicothema 27(1), 45-51. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.78

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J.W. (2008). Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behavior, 29(2), 129-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639620701457816

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J.W. (2012). School climate 2.0: Preventing cyberbullying and sexting one classroom at a time. School climate 2.0: Preventing cyberbullying and sexting one classroom at a time. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin Press.

Joseph, N. (2009). Metacognition Needed: Teaching middle and high school students to develop strategic learning skills. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 54(2), 99-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459880903217770

Klettke, B., Hallford, D.J., & Mellor, D.J. (2014). Sexting prevalence and correlates: A systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(1), 44-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.007

Korenis, P., & Billick, S.B. (2014). Forensic implications: Adolescent sexting and cyberbullying. Psychiatric Quarterly, 85(1), 97-101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-013-9277-z

Livingstone, S., & Smith, P.K. (2014). Annual research review: Harms experienced by child users of online and mobile technologies: The nature, prevalence and management of sexual and aggressive risks in the digital age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12197

Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Bullying in schools: the state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(1), 240-253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

Modecki, K. L., Barber, B.L., & Vernon, L. (2013). Mapping developmental precursors of cyber-Aggression: Trajectories of isk predict perpetration and victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(5), 651-661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9887-z

Nacimiento, L., Rosa, I., & Mora-Merchán, J.A. (2017). Valor predictivo de las habilidades metacognitivas en el afrontamiento en situaciones de bullying y cyberbullying. Informes Psicológicos, 17(2), 135-158. https://doi.org/10.18566/infpsic.v17n2a08

Ortega, R., Elipe, P., Mora-Merchán, J.A., Genta, M.L., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., & al. (2012). The emotional impact of bullying and cyberbullying on victims: a European cross-national study. Aggress. Behav. 38, 342-356. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21440

Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R., & Casas, J.A. (2016). Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 71-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.01.004

Powell, K.C.,& Cody, J.K. (2009). Cognitive and social constructivism: developing tools for and effective classroom. Education, 130(2), 241-250.

Prodócimo, E., Cerezo, F., & Arense, J.J. (2014). Acoso escolar: variables sociofamiliares como factores de riesgo o de protección. Behavioral Psychology, 22(2), 345-362.

Rimal, R.N., & Lapinski, M.K. (2015). A re-explication of social norms, ten years later. Communication Theory, 25(4), 393-409. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12080

Roncero, D., Andreu, J., & Peña, M.E. (2016). Procesos cognitivos distorsionados en la conducta agresiva y antisocial en adolescentes Distorted cognitive processes in aggressive and antisocial behavior in adolescents. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 26(1), 88-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apj.2016.04.002

Sastre, A. (2016). Yo a eso no juego. Madrid: Save the Children. https://bit.ly/1oDaq9U

Ttofi, M.M., & Farrington, D.P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 27-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1

Van-Royen, K., Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., & Adam, P. (2017). ‘Thinking before posting?’ Reducing cyber harassment on social networking sites through a reflective message. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 345-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.040