Abstract

This article addresses the measurement and validation of socially responsible human resource policies from academic and professional points of view. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has made great progress in recent years in the theoretical realm, showing its importance through different perspectives such as the institutional theory, the stakeholder approach, the theory of legitimacy, and the process of shared value. However, from an empirical standpoint, more research is needed to provide new indicators and evidence of testing socially responsible policies on business performance. This paper aims to devise a set of socially responsible human resource policies, demonstrate the validation of their content through several practices, and review the analysis of their relative weights thanks to the contribution of a panel of academic experts and a professional pretest, conducted in large Spanish companies.

JEL classification

M12;M14

Keywords

Corporate Social Responsibility;Human Resource Management;Panel of experts;Socially responsible policies

1. Introduction

In recent times, several researchers have started showing the relevance of undertaking socially responsible behaviours and actions by firms, and how this process could improve their financial results and relationships with stakeholders (Barrena-Martínez et al., 2016; Molina and Clemente, 2010 ; Saeidi et al., 2015). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has been defined by the European Commission (2011: 6) as the process of integration into business activities about the social, environmental, ethical and human concerns of their interest groups with a double aim: (1) to maximize the value creation of these groups; and (2) to identify, prevent and mitigate the adverse effects of organizational actions on the environment.

The previous definition revolves around the need to create value for all of the external and internal stakeholders, and the commitment to institutionalizing the responsible behaviour demanded by society. Employees are considered as one of the main internal stakeholders in the design and implementation of any organizational strategy. Hence, the satisfaction of workers and the value creation for them must be a key issue in the design of CSR strategies and organizational investments (De la Torre et al., 2015 ; Klimkiewicz and Beck-Krala, 2015). In this matter, it is of great importance to examine whether Human Resource Management (HRM) is assuming the challenge of introducing measurable and responsible indices that guarantee the sustainability for future generations.

Within an international scope, there are many indices which start to standardize and measure CSR policies and practices in the field of HRM. More specifically, Marimon, Alonso-Almeida, Rodríguez, and Cortez Alejandro (2012) highlight two of the main international CSR standards for their wide implementation by companies such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the ISO26000.

This study, based on the previous standards, aims to validate a set of Socially Responsible Human Resource Policies. Methodologically, the article provides results from a panel of experts over three rounds as well as a professional pretest, in which several human resource managers have participated. Finally, the study reports the content of eight socially responsible human resource policies, thirty-two practices and their relative weight. Professional implications, limitations and future lines of research are also presented at the end of the paper.

2. Designing an integrative model of Socially Responsible Human Resource Management (SR-HRM)

The integration of different research perspectives to explain an integrative model in the HRM field is one of the most relevant contributions extracted from the work of Martín-Alcázar, Romero-Fernández, and Sánchez-Gardey (2005). In this paper, Martin-Alcazar et al. propose a sequential and structured integrative model of human resources grounded on the premises of four complementary frameworks: universalistic, contingency, configurational and contextual.

Following the proposal by Martín-Alcázar et al. (2005) and Martín-Alcázar, Romero-Fernández, and Sánchez-Gardey (2008), this article explains the relevance and synergies of introducing socially responsible orientation in human resource management with regard to these four perspectives.

Firstly, the universalistic perspective of the integrative model of Socially Responsible Human Resource Management (SR-HRM) is based on the premise that there are universally successful recipes in the management of human capital for all firms (Delery and Doty, 1996 ; Fernández, 2001). Based on Martín-Alcázar et al. (2008), the first brick to lay in SR-HRM is the need to search for efficient human resource policies and practices, independent of the context, country or other variables. However, this is precisely the main weakness of the universalistic foundations, according to Delery and Doty (1996), namely, the lack of unity between practices and a coherent framework composed of relevant variables such as business strategy, the technology of the company, R + D investments, and other contextual variables. Taking into account the complexity of the environment, it seems logical that a wide number of external variables can affect the results of human resource practices. Therefore, the contingency perspective can contribute to this model by providing a better explanation of the effects and interactions between socially responsible human resource policies and the different internal contingency variables (structure, technology, size, business strategy, etc.) and external variables (organizational environment) with the aim of achieving a more consistent socially responsible system.

On the other hand, the third perspective, the configurational approach, has the value of defining a coherent system of socially responsible human resource policies through capturing the synergies and interactions of these policies with a larger number of internal and external variables. This adjustment can develop behavioural patterns in HRM defined by the organizational environment of the company, thus helping to improve the organizational performance. Specifically, Martín-Alcázar, Romero-Fernández, and Sánchez-Gardey (2009) show the value of the configurational perspective, examining how the combinations and synergies between policies and human resource practices encourage the consistency of HRM firms. In connection with our proposal, a socially responsible orientation must be coherent with the human resources strategy and CSR strategy, something that will provide consistency in the results of the policies and practices. Although the configurational approach provides a good explanation of the effects and interactions of the HRM system, we must consider the role played by institutional pressures and stakeholder requirements in order to gain a better understanding of the adjustments within the context. The contextual perspective could explain this fit (Brewster, 2004). The identification of contextual aspects has been developed in literature by several authors (Brewster, 1995 ; Ferris et al., 1998). In this article, we focus on two, from previous contributions: the socioeconomic context (legal, political, institutional, social, economic and environmental framework, the cultural aspect, trade unions and education system) and the organizational context (working-environment, company size, technology, innovation and interests of certain groups). Regarding the implementation of CSR actions, authors such as Bigné, Chumpitaz, Andreu, and Swaen (2005), Dahlsrud (2008) and Barrena-Martínez, López-Fernández, Márquez-Moreno, and Romero-Fernández (2015) emphasize the idea that this behaviour is increasingly implemented and internalized by companies and institutions. The Global Compact of United Nations, the OECD guidelines, the Green Book of CSR and the White Book in Spain are some of the important initiatives developed, in terms of sustainability. In addition to the international initiatives, there are also associations which develop CSR standards with wide implementation among companies, such as the Global Reporting Initiative and the ISO 26000, as referenced in Castka and Balzarova (2008) and Marimon et al. (2012).

In the Spanish context, there are two important bases for adopting CSR behaviours: the White paper on CSR and the constitution of 1978. In 2005, Spain created a Parliamentary Subcommittee to enhance and promote the social responsibility of business through the establishment of recommendations known as the White Paper on Corporate Social Responsibility. This document has been listed as the first document outlining a socio-economic approach adopted by a national parliament in Europe. It contains 59 appearances of various stakeholders (companies, trade unions, environmental associations, consumers, media, academic experts and regional governments). Additionally, as Fuentes-Ganzo (2006) stressed, the Spanish Constitution, in itself, sets a precedent for responsible behaviour (Article 1: categorizing Spain as a social and democratic state of law; Article 38: freedom recognizing company subordinate to the economic situation, Article 45.2: claiming the need and care of natural resources, taking collective solidarity account). Other legislation at national level emphasizes the importance of promoting socially responsible organizational behaviour, such as the Protection Law of Consumers and Users 26/84, Law 4/1989 of March 27 Conservation of Natural Areas Law 38/1995.

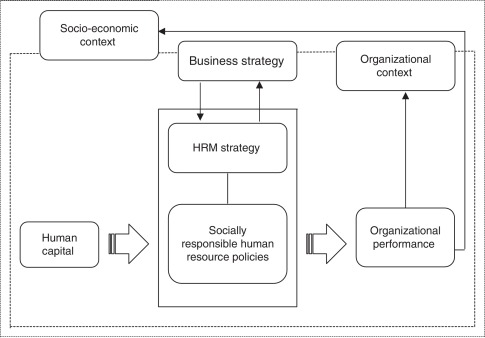

The influence of the previous political, legal and regulatory framework, according to Martín-Alcázar et al. (2005) has a decisive influence on modelling and processing human resource policies and practices in enterprises. Based on these contributions, we deduct the need to find a middle ground between human resource strategy, CSR strategy and the external demands of responsible behaviours as reflected in Fig. 1.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. System of Socially Responsible HRM. Source: Adaptation from Martín-Alcázar et al. (2005). |

After the theoretical framework of the research has been presented, we proceed to explain the process of developing and validating the content of the different socially responsible human resource policies and practices.

3. Method

With the intention of defining a set of human resource policies and practices that include a socially responsible concern for employees and their families, this study has three important tools:

- The analysis of professional content in CSR reports (Spanish IBEX-35 companies) and CSR standards (the GRI and ISO26000) based on Barrena-Martínez, López-Fernández, and Romero-Fernández (2013).

- The development of a panel of experts, aimed at achieving a consensus on the content of the policies and practices; and, (3) A pre-test composed of a number of human resource managers.

The use of this triple method of validation pursues the creation of a set of socially responsible policies and practices, not only able to improve organizational performance in economic terms, but also to focus on the social enhancement aims of improving the satisfaction and well-being of the employees. Following the definition of CSR, as proposed by the European Commission (2011), we can define the term ‘socially responsible human resource policies’ as those which: (1) improve the ethical, social, human and working conditions of workers, promoting their satisfaction and proper development in the company; and (2) obtain a differential added value for companies as a result of this process, increasing in the last term the global employees performance.

Firstly, we performed a detailed examination of the annual CSR reports of the companies that comprise the IBEX-35 (Spanish Stock Market Index) in 2012 from January to April. These companies are market leaders in Spain in terms of competitiveness and make up some of the 100 most responsible companies according to the Corporate Reputation Monitor (Merco1).

The analysis of the CSR reports aims to explore a consistent socially responsible pattern in HRM. Given the difficulty in finding a homogeneous proposal of policies and practices, and considering that most of these companies have certified their processes and management through CSR standards (Global Compact, Carbon Disclosure, DJS index, FTSE4Good), we searched for a common indicator in the majority of them. With the exception of Bankia and Dia, whose CSR reports of 2011, were not available on the date retrieved (January–April, 2012), we noted that 34 of the 36 companies (approximately 94%) had published social and sustainability reports verified by a common independent auditor belonging to the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).

Furthermore, the review of these reports, according to the indicators proposed by the Global Reporting Initiative, 2002; Global Reporting Initiative, 2006 ; Global Reporting Initiative, 2011, gave us a general overview of socially responsible patterns in human resource policies and practices. Specifically, as Table 1 shows, there are six common socially responsible human resource policies identified (Employment, Management of Labour Relations, Occupational Health and Safety at work, Training and Education, Diversity and Equal Opportunities and Equal Remuneration for women and men). According to the study of Marimon et al. (2012), which examines what the most implemented CSR international standards in business management are, we used a second CSR standard to complement the analysis, based on the ISO 26000. ISO 26000 is based on an international consensus among experts on CSR, who encourage the implementation of best practices in social responsibility worldwide. The correct application of this standard certifies socially responsible behaviour for companies in seven key areas of the organization: organizational governance, human rights, labour practices, environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues and active development, and community participation. The content analysis of ISO 26000 in the category of labour management reports the existence of two socially responsible human resource policies appropriate for this analysis (work conditions and social protection, and social dialogue). These two policies complement the previous six identified in the review of the GRI.

| Socially responsible HR policies | GRI | ISO 26000 |

|---|---|---|

| Employment | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labour management relations | ✓ | ✓ |

| Occupational health and safety | ✓ | ✓ |

| Training and education | ✓ | ✓ |

| Diversity and equal opportunities | ✓ | ✓ |

| Equal remuneration for women and men | ✓ | |

| Work conditions and social protection | ✓ | |

| Social dialogue | ✓ |

Source: Barrena-Martínez et al. (2013).

The analysis of the previous indices match a range of eight socially responsible human resources policies, as Barrena-Martínez et al. (2013) reports (see Table 1).

However, the GRI and ISO 26000 only provided indicators that verified the degree of compliance of policies and practices, without specifying their exact contents. Given this situation, a second method of content validity was used. To form this panel of experts, a Delphi methodology of three iterations was used.

As shown in previous literature, a panel of experts is of great utility for exploratory research that does not use already proven constructs (Landeta, 2006). Following the proposal by Astigarraga (2005) we identified four phases in order to correctly implement the Delphi: (a) the formulation of the research problem; (b) the choice of experts; (c) the development and delivery of the questionnaires; and (d) the practical development and examination of results.

In the first stage, we defined the need to find a degree of consensus about the theoretical content of the socially responsible human resource policies and practices as a main research problem.

In the second phase, we came up with four criteria when selecting the experts: (i) academic teaching and notable experience in HRM; (ii) the active participation in conferences, and seminars at national and international level; (iii) publications in the field of human resource management; and (iv) the participation as a reviewer or editor in HRM journals. The review of different academic profiles on the websites of Spanish and International Universities gave us a potential sample of participants for the panel. According to Astigarraga (2005), a sample, which takes into account 7 experts as a minimum, will be enough to bring about guaranteed results. This is because the success of the panel not only depends on the number of respondents, but also on the experience of the experts. Thus, 25 participants were pre-selected to make up the expert panel.

The third step was the development and launch of the questionnaires. In this survey the experts had to assess three criteria for all of the policies and practices: (a) that the policy/practice is correctly defined; (b) that the human resource practice is an element capable of defining a socially responsible policy; and (c) the percentage (relative weight) of the practice based on its importance in defining the policy (a relative weight of 25% was set by default for each of the four practices that defined each policy). These items have three possible answers: YES, NO or NA (no answer). Moreover, each policy included an open space for the experts to make suggestions and observations. The questionnaire was sent to the experts using the virtual platform SurveyMonkey. 2 In this correspondence, we defined the research objectives, the need to achieve a theoretical consensus about the policies and practices, the need for anonymity amongst the participants and the commitment to meeting the deadlines for each of the rounds. In three months (May, June and July 2012), all of the rounds were completed. The results of the different rounds are examined as follows.

4. Results

In the first round of Delphi, we obtained 18 responses from a total of 25 scholars. This round concluded in May 2012. In order to reach an agreement among the experts, we applied a criterion in which those human resources practices that enjoyed 80% or greater of the consensus among experts to be valid. This was in reference to: (i) theoretical content; (ii) whether this practice should be kept or not to define the policy; and (iii) the relative weight attributed to the practice. The information of the results is available in the permanent link (published on 13th April, 2016):http://jesusbarrenamartinez.blogspot.com.es/2016/04/rondas-1-y-2-panel-expertos.html

The review of the above link shows the consensus of the first round regarding the following socially responsible human resource practices:

- Attraction and retention of employees (practices 1.1, 1.2 and 1.4);

- Training and continuous development (practice 2.1);

- Management of employment relations (practice 3.4);

- Communication, transparency and social dialogue (practices 4.1, 4.2, 4.3 and 4.4);

- Diversity and equal opportunities (practices 5.1, 5.2 and 5.4);

- Fair remuneration and social benefits (practices 6.1, 6.2, 6.3 and 6.4);

- Prevention, occupational health and safety at work (practices 7.1, 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4);

- Work-Family Balance (practices 8.1, 8.2, 8.3 and 8.4).

In conclusion to the first round of results, we found that the socially responsible human resource policies 4, 6, 7 and 8 were perfectly understood in terms of their contents by the panel. Finally, a content analysis was performed to examine the definitions and suggestions of experts on each of the practices. The results can be found in the link above.

After analyzing the results of the first round, in June 2012 the second round was implemented. The results, conclusions and observations of the first round were sent to the participants to justify the criteria used to make the changes. Among these corrections, the requirement of experts for a definition of each of the socially responsible policies was highlighted, in order for there to be a proper understanding of their contents and practices.

In the second round, we registered 17 of the 18 academics involved in the first stage of Delphi, which represented approximately 94% of the share, receiving their answers at the end of June, 2012. These experts helped to shape the definitions and relative weights of the different socially responsible human resource practices. Considering the same percentage of consensus (80% or more), the 17 responses were examined.

After the second stage, the third round of Delphi was implemented; sending experts the corrections made to the items at the end of July 2012, and leaving open the possibility of feedback via email and telephone. The practical development and analysis of the results allowed us to validate the content of the socially responsible human resource policies.

After obtaining an academic consensus from the panel of experts, it was considered appropriate to perform a professional pre-test through face-to-face interviews with HR managers in order to properly validate the contents. This process improves the reliability and validity of the items (Báez & De Tudela, 2007). In order to accomplish this process, we randomly selected 15 large Spanish companies with more than 250 employees. We considered this size of company, because of the increased likelihood of there being a person responsible for the management of human capital. After contacting the human resources managers of these companies via phone or e-mail, 11 interviews were conducted with these professionals, which represented a 73.33% share of the initial forecast. A number of recommendations and suggestions helped us reformulate some items of the questionnaire, making them more understandable and easier to answer (Appendix I).

5. Conclusions, limitations & future research lines

The results of this article are a starting point in the debate on the formation of socially responsible human resource indices. The information revised in the CSR reports of IBEX-35 companies, the GRI and ISO 26000 standards during 2012, does not show a possible theoretical development on what we understand a socially responsible human resource policy to be, hence the academic challenge that arose at the beginning of this research. In order to meet this objective, a triple analysis was performed: the content review of CSR reports and standards, a panel of academic experts, and a pretest of interviews with human resource managers.

The review of CSR standards in terms of their content only proposed a checklist for verifying their accomplishments through undergoing an audit, which assesses this list positively or negatively. This aspect does not allow a practical agenda or plan of action in terms of designing a strategic implementation of socially responsible behaviours in HRM. Although the knowledge of corporate social responsibility in the area of human resources is increasing (Barrena-Martínez et al., 2015), this article contributes to the existing literature by providing practical and professional tools such as the CSR reports, GRI and ISO 26000 indicators for translating this implicit knowledge into practices measured day to day. This is precisely one of the strategic priorities of the European CSR Strategy 2011–2014, and consequently one of the professional concerns in Europe for any international company, which operates in this responsible framework. According to the definition of CSR presented by the European Commission, the socially responsible human resource policies and practices we present in this article must aim to achieve a dual purpose: improving the individual performance of employees, their satisfaction and commitment in a positive way, and increasing the economical and financial results of the company at an organizational level. As Triguero-Sánchez et al. (2015: 2) report ‘we need performance indicators that are much closer in terms that they indeed affect HRM practices’. Hence, one of the possible avenues for further research is to measure whether these eight socially responsible human resource policies could be associated with an increase in greater individual and organizational levels of performance.

From an academic point of view, the universalistic perspective represents a coherent HRM basis for testing the existence of the ‘best socially responsible policies’ which are able to bring about this double enhancement in results. Although, we proposed an integrative socially responsible human resource management model composed of complementary perspectives (universalistic, contingency, configurational and contextual), the universalistic approach provides a simpler and more linear way of understanding the relationship between HRM practices and performance.

Despite CSR receiving more attention from journals, conferences and academics, one of the most important aspects highlighted by experts in the rounds was the requirement of a clear definition for each of the socially responsible policies, given the general lack of awareness of how to understand them from a theoretical point of view.

Moreover, in the review of the experts recommendations, it was difficult to come to an agreement regarding the relative weights of the practices, according to their importance in the implementation of each of the policies that they encompassed. One possible reason for this academic incongruence is the difficulty in interpreting CSR actions as differentials, with it being necessary for all of the practices to go beyond the law in collective agreements as well as the Spanish institutional framework. This final aspect, which encompasses justifying the differential value of socially responsible human resource policies with regard to the traditional ones, is undoubtedly one of the major academic and professional limitations. The literature shows similar content in the High Performance Work System framework. In this aspect, socially responsible human resource practices try to add a new social nuance in managing people, with it being necessary that these policies fit the CSR, HRM and general strategy of the firm. Furthermore, the socially responsible orientation must go beyond legality and traditional economic objectives, aimed at achieving not only greater performance at the individual level employees, but also balancing the personal and professional expectations of workers, improving their welfare, and their commitment to the company.

With regard to future research, it would be of great interest to collect responses from executives of large Spanish companies that allow us to validate not only the content but also the statistical validity of the socially responsible policies of human resources. Another aspect of relevance would be to measure the effects of the previous policies on business results, from the universalistic, contingency, configurational and contextual perspectives.

With respect to the direct and indirect impact of these policies on HRM indicators, it would be valuable to analyze whether the socially responsible policies affect the absenteeism, turnover commitment or welfare ratios within the company. Studies such as Greco, Cricelli, and Grimaldi (2013) and Greco, Grimaldi, and Cricelli (2013) show the importance of not only indicators which are directly related to HRM productivity, but also the processes relating to social management, innovation and knowledge transfer. Hence, the relevance of measuring the effects of intangible and social indicators such as corporate social performance, intellectual capital or corporate reputation derived from responsible actions (Barrena-Martinez, 2013). Although this article presents a limited conceptual basis, it represents a vital starting point for testing the importance of the incorporation of socially responsible orientation into the field of human resource management.

Appendix I

Definition of socially responsible human resource policies and practices and their relative weights.

| 1. Attraction and retention of employees: set of activities that aim to facilitate the recruitment process, adaptation and integration and retention of new candidates as well as those most qualified for the organization. | Relative weight |

|---|---|

| 1.1. The tests used in recruitment and selection processes – search candidates, interviews, etc. – are inspired by the suitability of the candidate to the companys culture, training, opportunities for growth and promotion within the organization. | 30% |

| 1.2. Performs specific processes for adaptation and integration of new candidates in the company, delivering them a welcome manual, training on the culture of the company, etc. | 20% |

| 1.3. Sets transparent mechanisms for conducting internal promotion and communication activities of future vacancies and career plans, to make them accessible to the knowledge of all company employees. | 20% |

| 1.4. Promotes retention of skilled and experienced workers through motivational mechanisms and the implementation of an incentive program for meeting certain goals, awards for collaborative attitude, etc. | 30% |

| 2. Training and continuous development: activities that help employees to acquire the knowledge, skills and competencies they really need to perform their tasks appropriately within the company. | Relative weight |

| 2.1. Creates a working environment that stimulates learning, autonomy and a sense of aspiration and continuous improvement through group dynamics and interviews with employees. | 25% |

| 2.2. Periodically detects training needs of staff, establishing learning methodologies – face-to-face seminars, courses, etc. –; and (not face) – training on the intranet, distance learning courses, etc. – in order to improve these lacks. | 20% |

| 2.3. Performs regular performance reviews of employees in order to enhance their professional development and enrichment in their jobs. | 30% |

| 2.4. Promotes interaction and exchange of knowledge among employees through techniques such as internal rotation, group meetings or brainstorming. | 25% |

| 3. Management of employment relations: establishment of a series of activities to help to improve the relationship between the company and workers. | Relative weight |

| 3.1. It cares about achieving a comfortable work environment that respects the dignity of employees, helping to meet their needs and expectations of ethical character, social and employment. | 30% |

| 3.2. Facilitates interaction of workers with their representatives to encourage dialogue and conflict management with the company. | 20% |

| 3.3. Establishes regular meetings and other interaction mechanisms that facilitate a relationship of trust, honesty, reciprocity and commitment between managers and subordinates. | 25% |

| 3.4. Communicates and explains to employees at an earlier statutory minimum period, such changes and notifications that may affect its contractual relationship with the company. | 25% |

| 4. Communication, transparency and social dialogue: set of activities that facilitate the transmission, exchange and feedback between the company and employees. | Relative weight |

| 4.1. Establishes formal and informal communication among employees such as group meetings, personal interviews, newsletters or mailing lists via | 25% |

| 4.2. Communication with employees is transparent, providing information related to the actions and results of the company in the economic, social and environmental scope. | 25% |

| 4.3. Facilitates social dialogue between employees by creating a free media environment in which they can meet, trust each other, used to share information and consult regardless of their status or professional in the company. | 25% |

| 4.4. Encourages participation and the exchange of ideas among workers both horizontally and vertically, using tools such as quality circles, suggestion system, discussions, etc. | 25% |

| 5. Diversity and equal opportunities: set of actions that implement the principles of fairness and non-discrimination and promote the richness and diversity of the workforce in managing the workforce. | Relative weight |

| 5.1. Ensures the implementation of the principles of diversity and equal opportunities in all policies, practices and processes of human resource management of the company creating equality and diversity plans. | 35% |

| 5.2. Detects training needs in employees on diversity and equal opportunity through periodic assessments of their knowledge, in order to overcome these shortcomings. | 25% |

| 5.3. Power the principles of diversity and equal opportunities as essential criteria for excellence in composition, structure and management of the workforce. | 10% |

| 5.4. Creates diverse teams in order to develop ideas, group opinions, workflows and a higher level of creativity in the workforce. | 30% |

| 6. Fair remuneration and social benefits: set of economic rewards and social supplements received by employees fairly for their work. | Relative weight |

| 6.1. Ensures the principles of justice, fairness and transparency both internally and externally in the payment of employees. | 35% |

| 6.2. Remuneration to employees both in terms of the skills that have as their daily performance. | 30% |

| 6.3. Provides benefits to employees as a retention mechanism and encouragement, which are complementary to their remuneration economically scholarships for family, life insurance, checks care, retirement plan, medical service, participation in campaigns from NGOs, etc. | 20% |

| 6.4. Provides tools and resources that represent a direct economic cost savings to rental housing workers, vehicles, etc. – as well as improved working, social and family conditions. | 15% |

| 7. Prevention, health and safety at work: set of activities that seek to establish an appropriate level of welfare for employees and a culture of prevention that minimizes risks, physical and emotional injuries from work. | Relative weight |

| 7.1. Creates training programs and actions aimed at improving the prevention, occupational health and safety of employees that go beyond the legal requirements. | 25% |

| 7.2. Assigns monitoring and control tasks to their employees, in addition to the legally established, on health and safety in order to create a culture concerned with the prevention, physical and emotional well-being in the company. | 20% |

| 7.3. Certifies an appropriate level of safety and health for employees of the company through standards and certifications such as the OSHAS, ISOS, etc. | 25% |

| 7.4. Minimizes physical and emotional risks from work for employees and their families such as absenteeism, stress, occupational diseases and accidents at work. | 30% |

| 8. Work-family balance: set of actions to facilitate an appropriate balance between professional and personal life of employees, according to their needs as well as the needs of the company. | Relative weight |

| 8.1. Facilitates the existence of a proper balance between work and family life of employees. | 35% |

| 8.2. Facilitates modifications of working hours and shifts of employees according to their needs and those of the company. | 25% |

| 8.3. Provides flexibility in granting paternity and maternity leaves, lactation periods of absence, depending on the needs of employees and the company. | 20% |

| 8.4. Facilitates the transfer of employees to other work centres. | 20% |

References

- Astigarraga, 2005 E. Astigarraga; El método Delphi; Universidad de Deusto, San Sebastían (2005)

- Báez and De Tudela, 2007 J. Báez, P. De Tudela; Investigación cualitativa; Esic Editorial, Madrid (2007)

- Barrena-Martinez, 2013 J. Barrena-Martinez; Socially Responsible Human Resource Configurations and organizational results: Intellectual capital as a mediating variable; (2013) Universidad de Cádiz (Spain). Unpublished doctoral thesis. Facultad de Ciencias Economicas y Empresariales

- Barrena-Martínez et al., 2013 J. Barrena-Martínez, M. López-Fernández, P.M. Romero-Fernández; Towards the seeking of HRM policies with a socially responsible orientation: A comparative analysis between IBEX-35 firms and fortunes top 50 most admired companies; Tourism & Management Studies (Special Issue 2) (2013), pp. 488–501

- Barrena-Martínez et al., 2015 J. Barrena-Martínez, M. López-Fernández, C. Márquez-Moreno, P.M. Romero-Fernández; Corporate social responsibility in the process of attracting college graduates; Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22 (6) (2015), pp. 408–423

- Barrena-Martínez et al., 2016 J. Barrena-Martínez, M. López-Fernández, P.M. Romero-Fernández; Corporate social responsibility: Evolution through institutional and stakeholder perspectives; European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 25 (1) (2016), pp. 8–14

- Bigné et al., 2005 E. Bigné, R. Chumpitaz, L. Andreu, V. Swaen; Percepción de la responsabilidad social corporativa: Un análisis cross-cultural; Universia Business Review, 5 (1) (2005), pp. 14–27

- Brewster, 1995 C. Brewster; Towards a ‘European’ model of human resource management; Journal of International Business Studies, 26 (1) (1995), pp. 1–21

- Brewster, 2004 C. Brewster; European perspectives on human resource management; Human Resource Management Review, 14 (4) (2004), pp. 365–382

- European Commission, 2011 European Commission; Renewed EU Strategy for 2011–2014 on the social responsibility of companies; (2011) Brussels, October 25

- Dahlsrud, 2008 A. Dahlsrud; How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions; Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15 (1) (2008), pp. 1–13

- De la Torre et al., 2015 O. De la Torre, E. Galeana, D. Aguilasocho; The use of the sustainable investment against the broad market one. A first test in the Mexican stock market, Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa; (2015) http://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedee.2015.08.002 (in press)

- Delery and Doty, 1996 J.E. Delery, D.H. Doty; Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions; Academy of Management Journal, 39 (4) (1996), pp. 802–835

- Fernández, 2001 M.L. Fernández; Un análisis institucional del contexto y su incidencia en el proceso de cambio en la gestión de los recursos humanos; Tres estudios de casos (Doctoral dissertation, Tesis Doctoral) Universidad de Cádiz, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales (2001)

- Ferris et al., 1998 G.R. Ferris, M.M. Arthur, H.M. Berkson, D.M. Kaplan, G. Harrell-Cook, D.D. Frink; Toward a social context theory of the human resource management-organization effectiveness relationship; Human Resource Management Review, 8 (3) (1998), pp. 235–264

- Fuentes-Ganzo, 2006 E. Fuentes-Ganzo; La responsabilidad social corporativa. Su dimension normativa: Implicaciones para las empresas españolas; Pecvnia, 3 (2006), pp. 1–20

- Global Reporting Initiative, 2002 Global Reporting Initiative; Sustainability reporting guidelines; GRI, Boston, MA (2002)

- Global Reporting Initiative, 2006 Global Reporting Initiative; Sustainability reporting guidelines; GRI, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (2006)

- Global Reporting Initiative, 2011 Global Reporting Initiative; Sustainability reporting guidelines; (2011) Available at: https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/G3.1-Guidelines-Incl-Technical-Protocol.pdf

- Greco et al., 2013 M. Greco, L. Cricelli, M. Grimaldi; A strategic management framework of tangible and intangible assets; European Management Journal, 31 (1) (2013), pp. 55–66

- Greco et al., 2016 M. Greco, M. Grimaldi, L. Cricelli; An analysis of the open innovation effect on firm performance; European Management Journal (2016) http://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.02.008 (in press)

- Castka and Balzarova, 2008 P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova; ISO 26000 and supply chains—On the diffusion of the social responsibility standard; International Journal of Production Economics, 111 (2) (2008), pp. 274–286

- Klimkiewicz and Beck-Krala, 2015 K. Klimkiewicz, E. Beck-Krala; Responsible rewarding systems – the first step to explore the research area. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu; Social Responsibility of Organizations Directions of Changes (2015), pp. 66–79

- Landeta, 2006 J. Landeta; Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences; Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 73 (5) (2006), pp. 467–482

- Marimon et al., 2012 F. Marimon, M.d.M. Alonso-Almeida, M.d.P. Rodríguez, K.A. Cortez Alejandro; The worldwide diffusion of the global reporting initiative: What is the point?; Journal of Cleaner Production, 33 (2012), pp. 132–144

- Martín-Alcázar et al., 2005 F. Martín-Alcázar, P.M. Romero-Fernández, G. Sánchez-Gardey; Strategic human resource management: Integrating the universalistic, contingent, configurational and contextual perspectives; The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16 (5) (2005), pp. 633–659

- Martín-Alcázar et al., 2008 F. Martín-Alcázar, P.M. Romero-Fernández, G. Sánchez-Gardey; Human resource management as a field of research; British Journal of Management, 19 (2) (2008), pp. 103–119

- Martín-Alcázar et al., 2009 F. Martín-Alcázar, P.M. Romero-Fernández, G. Sánchez-Gardey; La investigación en dirección de recursos humanos: Análisis empírico de los procesos de construcción y comprobación de la teoría; Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 18 (3) (2009), pp. 37–64

- Molina and Clemente, 2010 M.C. Molina, I.M. Clemente; El comportamiento financiero de las empresas socialmente responsables; Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 16 (2) (2010), pp. 15–25

- Saeidi et al., 2015 S.P. Saeidi, S. Sofian, P. Saeidi, S.P. Saeidi, S.A. Saaeidi; How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction; Journal of Business Research, 68 (2) (2015), pp. 341–350

- Triguero-Sánchez et al., 2015 R. Triguero-Sánchez, J.C. Peña-Vinces, M. Sánchez-Apellániz; To what extent the employees’ diversity moderates the relationship among HRM practices and organizational performance: Evidences on Spanish firms; Tourism & Management Studies (2015) (in press). Available at: http://personal.us.es/jesuspvinces/HRM%20and%20Diversity%20in%20Spanish%20firm_%20Algarve%20(FINAL%20VERSION).pdf

Notes

1. The merco The Monitor Empresarial de Reputación Corporativa (MERCO) or Corporate Reputation Monitor analyses the corporate reputation of companies operating in Spain. It is a leading monitor on an international scale. Every year, over 700 companies apply, with only 100 of them reaching the general classification, in which EAE has been included for the eighth year running. The MERCO ranking takes the analysis of six key areas of each company into consideration: financial profitability, service quality and customer satisfaction, innovation, Corporate Social Responsibility and environmental policies, internal reputation and employment quality, and international dimension. Source: http://en.eae.es/about-eae/rankings/merco-ranking.html.

2. SurveyMonkey it is a Web platform that allows management software statistical surveys, emails and the tabulation of results exportable to other files. Source: https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk.

Document information

Published on 12/06/17

Submitted on 12/06/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?