Abstract

Housing development has become one of the main strategies to alleviate impoverished communities in developing countries. In the past, policies and programs focused on either economic or social aspects, and numerous imported solutions had failed to produce satisfactory results. At present, holistic approaches integrating all dimensions of human activity and environmental impact are gaining recognition as suitable alternatives for various experiences in developing nations. However, these approaches do not properly consider the local context, which is different for each case, thereby leading to inadequate models and unsuccessful implementations. This paper presents a context-driven and integrated approach for rural areas in developing nations for one of the most basic human endeavors, i.e., constructing a house. The self-building process utilized in constructing houses is a major strategy to help communities overcome poverty. Such a house must be capable of accommodating economic activities; must be durable yet flexible in layout and size; and must offer all basic services, including water, sanitation, and energy. Consequently, the Inclusive Housing Program is developed and employed in Oé-Cusse, a remote region of East Timor, as an integral part of the Regional Plan.

Keywords

Developing countries ; Rural settlements ; Housing program ; Adaptive housing

1. Introduction

This paper presents a strategy for developing rural regions through an inclusive housing program established and implemented in accordance with the Regional Plan of Oé-Cusse Ambeno in East Timor. Although this region includes an urban area (the capital city of Pante Macassar), the overall territory is primarily rural. The city has strong rural features because of the Indonesian occupation and socioeconomic stagnation. The proposed program aims to present an adaptive and resilient approach to development through housing at policy, guideline, and project levels. This approach considers the local economic, social, cultural, and environmental features, all of which are highlighted by the inclusion of concepts such as adaptability and multi-functionality.

In developing countries, majority of the investments in development are targeted toward urban areas because urbanization is a major driver of economic and social transformations (Satterthwaite, 2006 ). Large-scale modern activities, social infrastructures, and decision-making centers can be found only in urban centers (Basu, 1988 ). Such a scenario has led to internal migrations from the countryside, thereby resulting in informal settlements by arriving migrants who cannot find suitable living accommodations. Although poverty is highly prevalent in such urban settlements, people perceive the access to opportunities and employment in nearby cities as justifications for such living conditions (Satterthwaite, 2006 ; Christiaensen and Todo, 2014 ; Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy, 2015 ). This situation has become a closed loop in which the lack of a strategy for rural development leads to increased migrations to the cities, which in turn increasingly fail in meeting the demand for accommodations (Basu, 1988 ). Moreover, the lack of effective strategies for rural areas in developing countries has further worsened the living conditions because of the degradation of basic infrastructures (water, sewage, and energy networks), facilities (education and health), and mobility infrastructures for people and goods (Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy, 2015 ). From a long-term perspective, the rural–urban continuum might become broken, thereby causing severe consequences to the environment (Ward and Shackleton, 2016;Tacoli, 2003 ).

This problem has wider implications on the economy, society, and environment, and is therefore a major concern. It is one of the main issues in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) devised by the United Nations Development Program. This problem is directly linked to SDG 1, 6, 8, and 11 pertaining to poverty, access to infrastructure, and economic growth, all of which must be considered in creating sustainable cities and communities (United Nations, 2016 ).

The present study promotes the potential of housing as a strategy for development. Housing is considered in its broader meaning: “House is a noun and a verb [and] housing is both a process and an end-product” (Reeves, 2013 ). Vitruvio previously perceived the “house” as a shelter from a purely functional view (Hearn, 2006 ). In subsequent years, the significance of the house has become more complex. Rapoport (2003 ) described the house as a “primal site.” In other words, the house is the element attached to and influenced by human culture; it represents society, culture, and history, as well as its transformations. The “house” has a stronger significance in developing countries than in developed countries because it is a place not only for rest but also for generating income, working, and socializing (Wekesa et al., 2011 ; Werna, 2001 ). The daily lives of these populations occur in their own houses. Furthermore, an overwhelming majority of informal housing in developing countries are built by the occupants themselves, thereby strengthening their cultural and social attachment to the house.

Thus, the house, as both a living process and a product, can potentially become the primary strategy for development. This approach must be executed not at the project level, which reduces its impact and efficiency, but at the policy level. This paper presents an inclusive housing program implemented through the Regional Plan of Oé-Cusse Ambeno in East Timor. This program develops an adaptive and resilient approach for development through housing as well as for designing policies and guidelines by dropping the scale to the project level. The proposed approach considers the local economic, social, cultural, and environmental features, all of which are highlighted by the inclusion of concepts such as adaptability and multi-functionality. The process is supported by a public participation scheme to ensure adequacy and to promote community cohesion and shared responsibilities. The strategy was initially implemented through the Regional Plan of Oé-Cusse in June 2016, and solid results were obtained. The statistical results and main conclusions are obtained by further monitoring.

2. Literature review

This paper discusses the development process for building the strategy for the rural region of Oé-Cusse in East Timor through the regional plan of Oé-Cusse Ambeno and to promote development within an inclusive housing program. Since its East Timor became independent in 2002, its capital city of Díli, has rapidly developed, as stated in the country׳s Strategic Development Plan 2011–2030 (Governo da República Democrática de Timor-Leste, 2011 ).

In developing countries, majority of the investments are targeted toward urban areas, where the worst poverty and living conditions can be found (Christiaensen and Todo, 2014 ). This scenario results in migrations from the countryside. However, urban areas cannot meet the demand, and rural settlements become more isolated and thus underdeveloped, thereby creating a closed loop (Lucas, 2011 ; Basu, 1988 ). According to the Multidimensional Poverty Index of 2014, in a sample of 105 countries, 85% of the poorest people live in rural areas (Alkire et al., 2014 ). Donaghy (2013) claimed that in Brazil׳s rural areas, the main concern regarding poverty is the precarious nature of the dwellings themselves; by contrast, in urban areas, the concern is mainly related to the unsanitary conditions generated by overcrowding. This scenario occurs because in urban areas, “people are forced to cram themselves together in tight, often unsanitary and insecure conditions, whereas rural people are more likely to live in unsafe and perilous circumstances” (Donaghy, 2013 ).

In developing countries, isolation induces social, economic, and public health consequences, namely, social exclusion (low access to education, health, and social facilities); economic inactivity (informal and rudimentary economy, unemployment); and precarious living conditions (precarious housing and lack of basic infrastructures such as water, energy, and sewage systems) (Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy, 2015 ), (Porter, 2002 ; Yang et al ., 2016 ). Aside from those associated with major infrastructure projects, private investment is rare in rural areas (Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy, 2015 ; Christiaensen and Todo, 2014 ), thereby impeding development. However, policies and programs for stimulating rural development usually implement approaches based on agricultural production; they rarely include non-farming activities, neglect the need to diversify the local economy, and create a diversified economic environment (Tacoli, 1998 ). In general, the housing initiatives cannot adequately solve problems in the local context

From a rational perspective, housing solutions only suppress the physical problems of the housing stock (providing shelter, basic infrastructure, and building quality). This perspective is driven by an economic viewpoint (Amado and Ramalhete, 2015 ) and it disregards the social, cultural, and environmental adequacy of the house. Many public initiatives for low-cost housing adopt this path by implementing imported models focused on economic premises (Keivani and Werna, 2001 ), which hamper the development of the affected communities (Ramalhete et al., 2016 ).

In East Timor, the best example of such interventions is the Suco–Millennium Housing Program, which has been adopted after the independence; a suco is a territorial unit formed by small villages ( Fitzpatrick, 2012 ). The program implemented prefabricated houses in each suco , thereby resulting in several issues regarding adequacy. The houses lacked access to the public infrastructure network. All of the building materials were imported, thereby increasing the costs. The selected materials did not consider the bioclimatic context, resulting in the creation of uncomfortable and unhealthy homes. The layout failed to consider household dynamic and characteristics ( Wallis and Thu, 2013 ). As pointed out by Wallis and Thu (2013) , “The construction of social housing cannot be conceived merely as a technical feat but as a holistic understanding of local livelihoods and social realities” (Wallis and Thu, 2013 ). In addition, social and cultural features are more evident in rural than in urban settlements Tacoliau, 1998 ). East Timor also has a post-conflict factor, which emphasizes these features in society (Gunn, 1999 ).

Thus, the main challenge is selecting the approach that should be implemented to address the lack of financial, management, and human resources (i.e., skilled labor) while considering the adequacy of the program in the social context. All of these factors demand an adaptive and resilient approach. Progress has been achieved in this area through different approaches and methods, which are discussed in the following chapter.

2.1. Site and service schemes in the rural context

Site and service schemes are typically applied in contexts where the public sector cannot meet the housing demand by itself (Keivani and Werna, 2001 ). This approach is based on self-help in that the public sector acts as an indirect supporter of development by providing subdivided greenfield land with basic infrastructure and social facilities (Greene and Rojas 2008). In some cases, such a provision might include a small dwelling or a “sanitary core” (Gattoni, 2009 ), which can be expanded and/or upgraded by the inhabitants within an incremental process (Aravena and Iacobelli, 2013 ).

In both urban and rural settlements, this approach is hindered by two common issues, namely, scarcity of space and financial means, in this order of importance (MIT Center for Advanced Urbanism, 2016 ). For urban slums, the main problem is the available land for infrastructures and facilities, whereas for rural areas, the scarcity of financial resources is the main issue. In most cases, rural settlements do not justify such huge investments on infrastructure and facilities because of the number of inhabitants and/or the remoteness of their location (MIT Center for Advanced Urbanism, 2016 ). This problem, along with lack of coordination between stakeholders and bureaucracy, leads to the failure of the approach, particularly in rural areas (Blaustein et al., 2014 ). To reverse this trend, community-scale infrastructure was adopted for water and wastewater treatment (Moglia et al ., 2010 ; Ray and Jain, 2014 ). One example is EcoSan in Nepal, where biogas-attached toilets (which, aside from sanitation, produce energy and slurry compost) were adopted in several rural areas (WaterAid, 2008 ), providing not only effective sanitation but also promoting the sustainability and self-sufficiency of the settlement. This project built 517 EcoSan toilets in seven districts of Nepal for five years. In rural Kenya, 2000 bio-sand filters were built in two villages to solve the drinking water problem (Native Energy Inc., 2012 ). This solution is economically viable in rural areas until centralized systems are applied because installation can be performed easily by the population. The filters were prefabricated elements without no moving parts that need repair or replacement, and electricity or plumbing is not necessary because the filtration units are gravity-fed (Native Energy Inc., 2012 ). Centralized systems are often costly to build and operate, particularly in low-density and dispersed settlements (Massoud, Tarhini, and Nasr, 2009 ). By contrast, decentralized infrastructures “can be designed for a specific site, thus overcoming the problems associated with the site conditions” (Massoud et al., 2009 ). This practice will “allow more flexibility in management, and a series of processes can be combined to meet the treatment goals and address environmental and public health protection requirements” (Massoud et al., 2009 ). Although not a long-term solution, such a strategy facilitates an incremental implementation. In other words, the solution will be gradually upgraded to centralized systems according to settlement development and growth (Massoud et al., 2009 ).

The same type of constraint can be found in the provision of public facilities. Given that building a school or a clinic is not viable in rural settlements, a wider approach is necessary. For example, this approach can be observed in East Timor, where several schools practice rotating systems among several grades. This approach is also demonstrated by the School Plus Program in England, which offers services to the community and provides a physical space for other activities inside school buildings (André et al., 2012 ).

Although the public sector provides the land, basic infrastructure, and facilities, the population is responsible for the houses in the self-building context. In this way, the housing deficit can be easily solved by using an existing characteristic of informal settlements, i.e., the ability of people to build their own homes (Gattoni, 2009 ). Turner and Fichter (1973, cited by Gattoni, 2009 ) posited that if the strategies used by the poor were recognized and supported, these strategies might become effective solutions for the housing deficit. However, the lack of technical skills and resources (quality materials) results in the creation of precarious housing units that are similar to what they previously had (Abbott, 2002 , Amado, 2005 ). Unlike the overcrowded and unhealthy housing stock of the cities, precarious housing in rural settlements is marked by low-quality and unsafe building systems, precarious materials, and inefficient designs, i.e., the house functions merely as a simple shelter (Ramalhete et al., 2016 ).

In site and service schemes, some examples were effectively applied and evaluated. One such example is the Aranya Housing Project in India in 1988. This project built approximately 6500 dwellings (serviced by water, storm water drainage, sewer connection, paved access, and public lightening) and was aimed at population with different levels of income, thereby promoting social inclusion (mixed incomes). This project attempted to provide an “architectural vocabulary suitable to both socioeconomic circumstances and the climate [passive solutions]” (Vastu-Shilpa Foundation and Doshi, 1989 ) through assisted self-building. People incrementally built their houses according to the 80 housing models provided by the technical team. The houses varied from a one-room shelter to a large house, all with a service core (infrastructure) and a plinth for further expansion depending on the family income (Vastu-Shilpa Foundation and Doshi, 1989 ). Evaluation studies conducted in 2010 (McGill University, 2010 ) showed that the building stock had improved significantly. People initially used inexpensive materials; however, after social and economic development in later stages, the occupants started applying sturdier and permanent materials, such as reinforced concrete. They also began expanding their houses according to their needs. Such an approach was also applied in the national housing program in Chile in 1993 by allocating plots with a housing core for further expansion (Greene et al., 2008 ; Beattie et al., 2010 ). The Elemental Project, which was of a smaller scale than Aranya, was a result of a public strategy targeted toward both urban (Quinta Monroy, 93 dwellings, 2004) and rural areas (Villa Verde, 484 dwellings, 2013) (Aravena and Iacobelli, 2013 ).

Majority of site and service schemes are supported by a public participation model that encourages communities and local leaders to implement the projects by themselves, thereby promoting social cohesion and shared responsibilities. Community involvement is an ongoing process that starts in the design phase (identification of needs and design of adequate solutions) and continues throughout the monitoring stage (maintaining the housing stock and the public space, among others) (Gattoni, 2009 ).

Site and service schemes are among the most viable solutions for regeneration strategies and housing provision (Devas and Rakodi, 1994 ). However, delays can result from the lack of coordination among stakeholders, which is more apparent in rural settlements. The absence of technical assistance for housing design and building is another major constrain.

2.2. Adaption of building standards: adequacy to economic, social, and cultural context

The adaptation of building standards is generally related to site and service schemes. One of the few constrains of this solution is the slow rate of occupancy because of the lack of financial capacity of households (Wekesa et al., 2011 ; Gattoni, 2009 ). In most cases, these families cannot mobilize savings or obtain financing to build a house that meets the building standards and codes. Another problem is the inadequacy of the building standards with respect to the social and cultural features of the community. As mentioned, in developing countries, the house is simultaneously a shelter and a source of income. This notion is apparent in both urban and rural settlements. In the latter, the main economic activity is agriculture, and the housing plot is often directly adjacent to the farming area or to areas reserved for storage and transformation of produce (Wekesa et al., 2011 ). Nevertheless, other economic activities can be observed, such as handcrafting, weaving, pottery, and carpentry (Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy, 2015 ). According to Ward and Shackleton (2016) , “[r]ural livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa is a different context but nonetheless an area of poverty, and underdevelopment often incorporate non-farm strategies, such as urban-based employment, to supplement the use of land-based strategies.”

Consequently, the adaption of building standards is important to ensure positive results in the housing program. This approach must be supported by the public sector by passing legislation that integrates the concept of home employment (Wekesa et al., 2011 ; Werna, 2001 ). Housing programs and projects should allow for new functions in the housing plot, such as small-scale manufacturing workshops or other activities that do not compromise public health. Such actions should determine the housing size, design, and layout.

Although this approach is suitable for solving the housing deficit and for complementing strategies, such as site and service schemes, the criteria for adapting existing building standards must be carefully evaluated to ensure the minimum conditions regarding safety, quality, and comfort (Amado et al., 2016 ).

The gender issue is a sensible theme in Oé-Cusse because the traditional behavior and low income of families are problems that affect the housing dimension. This new methodology can provide access to adaptive housing and promote better conditions regarding the privacy and lifestyle of male and female residents.

2.3. Partnership scheme

The partnership scheme reduces the public financial effort on regeneration and housing provision, which is also implanted in site and service schemes. The partnership involves the public sector, the private sector, the local community, and the population in regeneration areas, with the objective of developing social and affordable housing (Amado et al ., 2016 ; Mukhija, 2004 ).

Similar to that in site and service schemes, the government in this strategy plays a financial and regulatory role by implementing subsidies, managing of land tenure, and providing the basic infrastructure. Formally, the public sector encourages private investment through tax advantages, incentives, and the opportunity to generate profit from land valorization. The latter is achieved through the creation of major infrastructures (mobility and basic infrastructures) and facilities (Amado et al., 2016 ). However, the government usually holds the responsibility of providing affordable housing for the population with few financial means. It can achieve this social objective by providing social housing based on subsidized rentals (Wekesa et al., 2011 ).

Several authors have discussed different partnership schemes and the effective role of the private sector in providing low-cost housing. In Luanda, Angola, the public sector provides land and infrastructure provision as well as a small allocation of social housing within the national housing program, whereas the private sector offers services, commerce, and housing units directed at the free market, as well as affordable units (Amado et al., 2016 ). The latter might be allocated in the regeneration area or transferred to other locations depending on the demand, urban density, and other factors. This method is similar to the Transferable Development Rights implemented in India (Nijman, 2008 ). In the Turkish approach, the private sector must provide developed land within the government-owned land (Akkar, 2006 ). In Iran, land is provided by the state, and units are subsequently delivered by private developers and co-operatives (Keivani et al., 2008 ). The Moroccan approach, which is based on taxation and financial benefits, adopts a model that uses tax breaks to encourage the private sector to build affordable housing (Zemni and Bogaert, 2011 ).

Thus, partnership schemes rely on the local political, economic, and social contexts as well as on the potential of an inclusive housing program for development. A wider overview is presented for the current political, social, and economic contexts, which are directly linked to land tenure, housing features, and prevailing economic activities (and consequent source of income). The scale of the housing problem and the needed financial effort are important factors to consider. The examples are taken from urban informal settlements and slums. The adaptation to rural settlements must be carefully assessed because the interest of the private sector depends on the region and its opportunities to develop projects.

3. Potential of an inclusive housing program for development

The Region of Oé-Cusse in East Timor has developed rapidly since the implementation of the new Social Market Economic Administrative Region. This new strategy will develop a new paradigm of integrated development based on an inclusive, participatory, and efficient model of socioeconomic growth. The development of a methodology for an inclusive housing program is framed by the regional plan for Oé-Cusse Ambeno, which is a region with many challenges to overcome.

Apart from being an enclave, which geographically isolates the territory, biophysical features and past conflicts (such as the Indonesian invasion) have hampered the development of Oé-Cusse (Bugalski, 2010 ). Its context is marked by informality, lack of infrastructure, and low family income. On the one hand, housing stock has no basic infrastructure service and is built with precarious building materials that can generate public health problems. On the other hand, previous conflicts resulted in strong community bonds and identity because the home acquires much significance, such as a shelter and wealth generator as well as devotional, social, and familiar meanings (Fitzpatrick, 2012 ; Werna, 2001 ). All daily economic activities that occur in the housing plot are critical features of daily living. According to the 2010 census, most of the families in the Oé-Cusse Region work in agriculture, and small businesses may be located inside or near the housing plot itself. The self-building of homes plays an important role in creating a sense of belonging and pride.

The land tenure process is unclear because of recent political transformations. Majority of the land tenure are based on a customary law. Land titles from the Portuguese and Indonesian periods are of dubious application (Fitzpatrick, 2012 ). In Oé-Cusse, the process is partially informal; that is, the public sector (through the regional planning department) is aware of the land owners/users and is even the manager of the land but devoid of any legal framework. This practice has several implications in the territorial and environmental context.

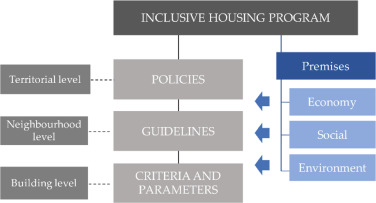

Housing is an important factor for economic and social development that molds territories. That is, “territories are shaped by housing insofar as housing contributes to the creation of a particular territory, as in the shaping or urban blocks and the making of submultiple or infill arrangements” (Rowe and Kan, 2014 ). An inclusive housing program comprising of different levels of approaches and a wide coverage of the economic, social, and environmental context will facilitate an intervention at the territorial level though policies, at the neighborhood level through guidelines (Fig. 1 ), and at the building level through criteria and parameters for adequate housing.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Inclusive housing program: levels of approach. |

The process is accompanied by a public participation scheme to ensure adequacy and promote community cohesion and shared responsibilities. This participation is integrated in the policies as well as in the design and building process.

This paper attempts to answer how an inclusive approach can contribute to solve the housing problem and promote the development of rural areas under the condition of missing governance and with financial, human, and material resources as major constrains. The necessity to work with the local potential to solve the identified needs is highlighted by this question. Furthermore, rather than solving immediate problems, this approach recognizes the need to be adaptive and resilient to future economic and social transformations that will occur in the territory. Thus, a theoretical framework should be established to ensure the adequacy of an empirical and holistic approach.

4. Methodology

The methodology is based on both theoretical and empirical evidence. The latter is particularly important because of the need to adjust the final model to the existing context.

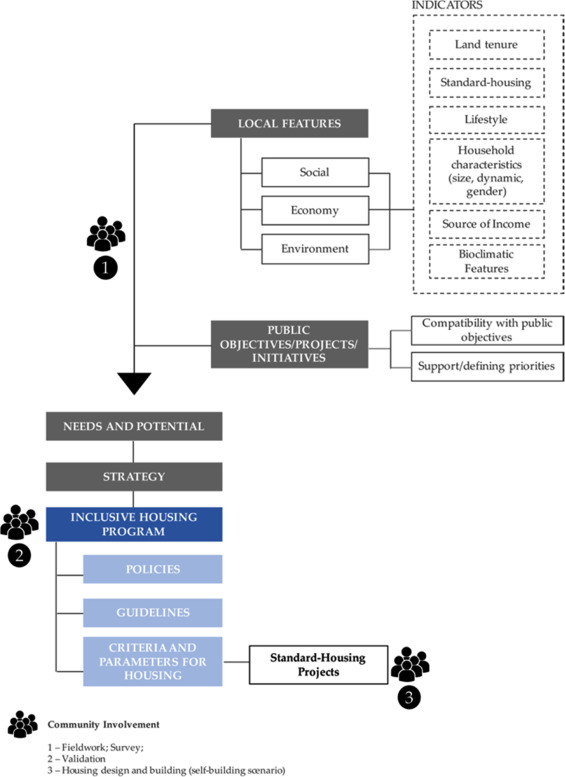

The first stage involves the analysis of local social, economic, and environmental features. A set of indicators are considered, such as land tenure, local dwelling types, lifestyles (concerning housing), household characteristics, source of income, and climate. Land tenure is the first main indicator because it is a fundamental element of the inclusive housing program to define the public and private roles at the policy level. The analysis of standard dwelling types, together with the assessment of local lifestyles, yields the key features that must be considered when designing new homes: how people live and use the house/plot, and how such use defines the layout. Household characteristics, such as the size, dynamics, and gender of the family members, are also important, because these data clarify the housing typology, layout, and incremental schemes. In this context, the source of income is also an important indicator. The source of income, regardless of whether it is agriculture, small businesses, and/or workshops, is usually installed in the housing plot, and this feature should be considered when defining policies and designing new housing models. Finally, bioclimatic analysis ensures the adequacy of housing to the local environment.

The needs and potential of the Oé-Cusse Region have detailed features based on empirical data (fieldwork and survey), namely, land tenure, housing layout, building systems, materials, and economic activities linked to the housing plot. Based on our experience, fieldwork, and the public participation process, these features were the most important to be considered in guaranteeing the effectiveness of the strategy.

To obtain solid evidence, the methodology introduces public participation sessions with local communities. These sessions involved the Suco Council, which is a small community council formed by an elected leader and his political appointees for different areas, such as agriculture, youth, and women. These representatives (between 10 and 12 people) acted on behalf of the community. The sessions were conducted by the team with a local translator of Portuguese and Tétum (both official languages in East Timor) and consisted of two stages. The first stage was a group survey where the council was consulted in several areas. This survey was conducted by the team and all council members freely discussed and answered. The second stage consisted of validating the survey through fieldwork. The members of the council arranged a visit to the suco , showing its main features in terms of social, economic, and environmental aspects. Through observations and contact with the local setting and the people, the team validated the data gathered in the surveys.

The survey considered the following aspects: (I) Origin and occupation; (II) Activities and eating habits; (III) Water, sewage, and waste treatment; (IV) Access to facilities; and (V) Housing.

This stage includes the assessment of the public objectives, initiatives, and projects promoted by the regional authority, which is responsible for the future implementation of the program. At this stage, the compatibility of the proposed strategy for the inclusive housing program is also tested with respect to other current projects.

Identifying the needs and local potential is the main goal of the strategy for the inclusive housing program. The policies, guidelines, criteria, and parameters for housing are founded on these needs and potential to use local resources (potential) to solve the problems (needs). This stage also includes public participation for validation. The Suco Council was consulted to validate the program. If needed, changes and adaptions were introduced. This process ensures the people׳s involvement through shared responsibilities.

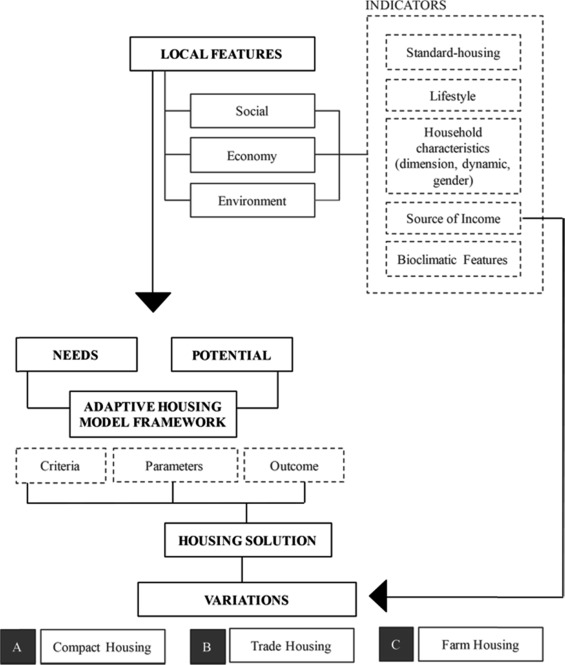

The inclusive housing program consists of three levels of approaches. The first refers to the policies that influence and determine the decisions and actions. The design of proposals and policies defines the working process, partnership scheme, and role of each stakeholder (state, private sector, and population). The second level refers to the general guidelines for an adaptive and sustainable settlement and housing stock. The third level occurs at the building level, at which the criteria and parameters for housing design and their outcomes are considered. This theoretical framework, which is divided into three fields, namely, social, economic, and environment, can provide insights into future housing projects. These units are to be built through a self-building process, and a public participation workshop will support the final housing design options. Fig. 2 .

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Methodology for inclusive housing programs. |

5. Discussion

This paper presents the development of an inclusive housing program for the development of the Oé-Cusse Ambeno Region. The objective of the program is to promote development by solving the housing problem in the region and introducing a new approach for housing development based on inclusive, adaptive, adequate, and sustainable concepts. The lack of financial resources and skilled labor is one of the major constraints of the region. This dilemma introduces the following query: How can the housing program promote development by using the local potential in an inclusive partnership among all stakeholders?

This work proposes a new approach for the housing program by combining a theoretical and holistic framework with an empirical approach to obtain a practical result. In the literature review, these research methods are discussed with respect to the currently applied rural regeneration approaches. Different findings made by various authors are presented, focusing on understanding the positive and negative component of each feature. The contribution of this study is the introduction of an inclusive methodology for housing programs that extends the theoretical approach and solves the immediate problems, making it a widely applicable and sustainable approach. This long-term inclusive approach is supported by population actions and regional institutions. It also includes several operative scales (territory, neighborhood, and building levels). Such considerations are helpful to clarify the current housing problem as well as the economic and social constraints in developing countries.

The power relations in the Oé-Cusse Region are culturally based on male dominance in making decisions concerning all family matters. The current governance model in the region considers the transformation of the women׳s role in the region, and the influence of such transformation on the design of the housing program. The developed polices are related to agriculture, arts, and crafts, which employ a significant number of women working at home. The housing program was created to answer these needs through established criteria and parameters, such as the plot dimension and urbanization process, to provide access to utilities. This approach creates better conditions and facilitates working at home. This participatory context can be replicated given the results of previous experience in preparing the Oé-Cusse Regional Plan and designing the housing program developed under this plan.

5.1. Needs and potential of Oé-Cusse region

The first step of the methodology identifies the main needs and potential of the housing stock. From a total of 18 existing sucos , 11 were selected because of their dimensions to be surveyed within the framework of the development of the regional plan, where this strategy is integrated. In addition to surveys and public participation, the group conducted extensive fieldwork to assess in detail the local housing stock features and people׳s lifestyle.

The first assessment was based on the needs brought forward by the population regarding their housing (the survey included other aspects such as access to social facilities, mobility, and education). Access to infrastructure was voted with the highest priority, particularly the settlements located deep in the mountains or in remote locations. The definition of property boundaries was the second-highest issue in terms of importance. Land tenure is constructed by an informal process that is mainly managed at the suco level by an elected leader, who then informs the regional secretary acting as the government authority. Plots are well defined by the fences, and their expansion is agreed at the Suco Council. The third consideration pertains to the used materials and building systems, which are precarious and vulnerable to storms in most cases.

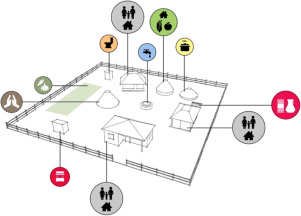

Housing stock conditions have specific features that constrain quality of life in terms not only of materials and building systems but the layout. The house has a specific layout that reflects the local lifestyle. The house comprises several small buildings (Fig. 3 ), such as the bedroom/living room (usually built in cement blocks or a mixed system of straw and canes); the latrine, which might be built in cement blocks or a simple straw wall with no roof; the kitchen, where the fireplace with a cover made of straw is located; and the storage building is also built with straw. Some examples present small workshops for pottery or weaving near the kitchen, a devotional building or altar, or a small business hut for selling products (usually located near the road). In terms of layout, all of these buildings are located around the well, which is the central point of the house. The majority of the plots have an orchard for subsistence farming.

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Standard house in Oé-Cusse Region. |

Several households live in one plot, and their number is associated with the bedroom/living room building (each household has one). The number of buildings grows incrementally in that a new bedroom/living room building is built for each son that gets married.

The major needs identified from the fieldwork and surveys are related to the lack of access to utilities (water, energy, and sewage) and the deficient condition of the housing stock in terms of building materials and construction methods. Although 100% of the territory is already covered by the public power network, the housing stock does not yet have the equipment to make the connection to it. Thus, people still use fire and/or small diesel generators both in the urban area of Pante Macassar and in rural areas. According to the field survey, drinking water is accessed mainly through wells, and the sewage network does not exist at all (the common solution is using private latrines).

The region also has potential for implementing housing initiatives. First, the population must be self-determined to design and build their own houses even without financial resources and materials mainly in remote locations. This feature is crucial to the success of a self-building process. Cultural and social cohesion helps in this process; that is, the community is generally supportive of actions that result in the construction of new buildings. According to the surveys in the sample of Pante Macassar (urban area), 62% of the households built their own houses, whereas the remaining 38% paid other people to perform this task. In rural areas, all families built their own houses with their own resources.

The existence of other functions on the housing plot is another major advantage that should be considered. In addition to a small area for subsistence agriculture, 11% of the surveyed households in Pante Macassar had a small business in the housing plot. In rural areas, this percentage is lower (2%) because people work mostly in agriculture. Moreover, most of the families work informally in subsistence agriculture and/or crafts (weaving, pottery, and carpentry). In urban areas, this condition represents 31% of the surveyed population and is a constant factor.

To solve this issue, the regional government is leading several initiatives to foster development. The main one is the development of a regional plan based on the vision of Oé-Cusse as a “green region”. This plan provided the main guidelines for the present study and considered the region׳s potential for small-scale tourism (community tourism) and environmental protection through the clear definition of the rural settlement boundaries.

5.2. Inclusive partnership

Private and public actors are present in the housing sector in the Oé-Cusse Region. The region recently started its development through a regional authority. The regional Plan (2015) was the first major project for this purpose. The new development actions are now attracting private investment, and the opportunity to build an inclusive housing program with the support of the regional authority (public sector) has emerged. Thus, private/public relationships are now being created, and the effectiveness and sustainability of the relationships are provided. Similarly, actions of entrepreneurship significantly have an important effect after the Housing Program was implemented.

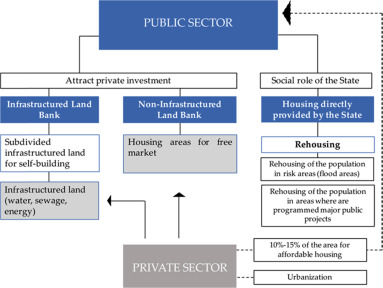

The effectiveness of the housing program lies at the policy level. These policies should clearly define the roles of the stakeholders, namely, the public sector (local authority), private sector, and population, within the housing provision. Following the aforementioned trends, the public sector is perceived as a facilitator rather than a provider to reduce the financial efforts and achieve a more viable approach. Therefore, the public sector is responsible for land management to attract private investment (Fig. 4 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Inclusive housing program strategy. |

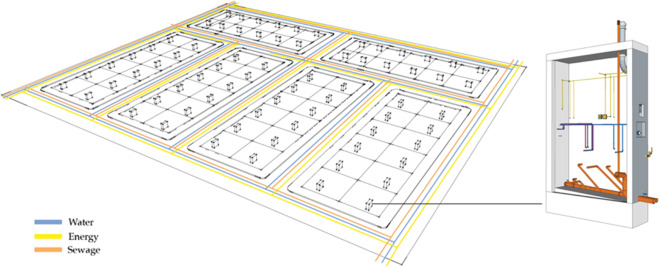

This objective is achieved through two formats: the infrastructure land bank and non-infrastructure land bank. The former refers to a land bank developed by the public sector, and it includes its subdivision and the implementation of infrastructures (water, sewage, and energy systems) to support the self-building process. Inside each plot is an infrastructure core (technical wall) guaranteeing that each dwelling has access to public infrastructures of utilities. The region is mainly rural and rugged, suggesting that a huge system of public infrastructure constitutes networks in some areas. Therefore, community-scale infrastructures, such as bio-sand filters for water treatment and compact wastewater treatment for sewage, can be considered as alternative solutions. In the long term, a part of this community-scale infrastructure can be upgraded according to demand and connected to large systems. The subdivided urbanized land is distributed to the population (through selling, long-term use authorization, and assisted rent), according to previously assessed land rights and needs, so that people can build their own houses (Fig. 5 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 5. Infrastructure land bank with technical wall for self-building. |

The other option of the infrastructure land bank is directed at harnessing private sector investment. The state provides infrastructured land for urbanization by the private sector. In both cases, the state provides surface rights to the users through a variable tax. The value of this tax considers the source of income, size, and age structure of the household. The other format is based on the private sector and is referred to as the provision of non-infrastructured land for real-estate development aimed at the free market. In both formats, the private sector must ensure 10–15% of the urbanized area for affordable housing to contribute to the housing program provision in exchange for the transmission of free land to urbanize. This affordable housing provision can urbanize other locations according to the regulations defined in the Regional Plan of Oé-Cusse Ambeno.

However, the state has a social role of providing housing within rehousing scenarios. These scenarios include people living in risk areas, such as flood-prone districts, and people living in areas where major public projects, such as the Oé-Cusse airport expansion, are intended. In this format, housing is directly provided by public funds in areas that should consider the proximity to the original site and the household source of income.

This approach allows the sharing of financial efforts among stakeholders. The public sector should ensure the conditions not only for development through land and infrastructure provision but also for rehousing as a social role. The private sector, aside from playing a role in urbanization and development within the free market, should accommodate a percentage of affordable housing in exchange for the land and infrastructure, thereby resulting in a shared responsibility for the housing provision. Self-building is an incremental process in which the population can expand and upgrade the housing stock according to needs and financial capacity.

5.3. Guidelines for inclusive housing

The housing program strategy requires long-term actions. The definitions of specific policies that will influence and determine decisions, actions, and guidelines are important tools for assuring the connection between the policy level, housing framework, and development of standard modular projects. These guidelines are composed of the following good practices for supporting the adaptive housing framework:

- implementation of an incremental process to ensure economic feasibility linked to financial capacity and needs;

- legal support to flexible housing models;

- diversity of housing typology to better serve the householder׳s characteristics, and implementing international standards on overcrowding, household size, and gender;

- minimum areas for sanitary reasons and thermal comfort in view of the environmental and economic premises for building costs, energy consumption, and resource management;

- multifunctional housing that considers the household income;

- applying a bioclimatic design with passive solutions for cooling, cross ventilation, and lighting to ensure thermal comfort, decreased consumption, and fewer environmental impacts;

- selection of materials extracted/produced locally (natural or composite) according to their performance, quality, and cost;

- mixed building systems with natural and composite materials that result in decreased building costs and environmental impacts.

The aforementioned systems facilitate the self-building process by using techniques that are familiar to the population. This aspect is related to prefabrication, which is strongly encouraged in the Housing Program because of the economic benefits that it provides (Stallen and Chabannes, 1994 ). According to the field survey, cement blocks/bricks and prefabricated structures (e.g., concrete) are viable solutions for application in the region. First, bricks and blocks are already produced in small local factories in the region. Second, the commercial port will enable easy access to the East Timor mainland. Finally, ongoing road investments determine the tradeoff between the Oé-Cusse Region and the Indonesian border. Although these solutions seem initially problematic because of the transportation costs, the durability and quality of the materials compensate and balance this flaw (Stallen and Chabannes, 1994 ).

These guidelines will provide the following framework for future housing: adequacy in household needs, adequacy in the social and cultural contexts, social inclusion, acceptance, public health, affordability, thermal comfort, decreased costs, economic development, improved quality (durability), reduced energy consumption, and enhanced resource management.

5.4. Adaptive housing framework

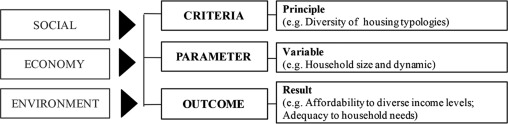

As mentioned, the effectiveness of the strategy of the inclusive housing program for the Oé-Cusse Region is dependent on its continuous process. This condition is achieved by the creation of houses that ensure safety, quality, capability to adapt, and adequacy in household needs. Most houses promoted by standard programs showed a lack of identity or a difficulty in adapting to the social, economic, and environmental reality. In comparison, previous incremental processes were supported by the population, resulting in precarious housing because of the lack of technical knowledge and adequate assistance (Aravena and Iacobelli, 2013 ; Greene and Rojas 2008). Therefore, a framework for developing quality homes is indeed necessary. Nonetheless, this framework must allow adaption to the local context. That is, the main criteria and parameters considered are based on the local context, which are then interpreted and performed by the population with the assistance of technical staff. Fig. 6 and Table 1 , Table 2 ; Table 3 highlight the list of criteria and parameters, and the result of their implementation to better understand how the criteria were developed.

|

|

|

Fig. 6. Inclusive housing program: levels of approach. |

| Criteria | Parameter (s) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Diversity of housing typology | Household dimension and dynamic; International criteria for overcrowding | Affordability; adequacy in household needs |

| Housing flexibility (expansion) | Household dimension and dynamic; International criteria for overcrowding | Adequacy in household needs |

| Optimization of housing layout | Household cultural aspects; Household economic activities | Adequacy in household lifestyle and culture; Individual and collective development; |

| Assisted self-building process | Household/community skills and capacity | Facilitating appropriation process; social inclusion; identity; skills improvement; individual and collective development |

| Application of materials produced/extracted locally | Cost, quality, and performance | Facilitating the appropriation process; social inclusion; collective identity |

| Multifunctional housing | Lifestyle | Adequacy in household lifestyle and culture |

| Criteria | Parameter (s) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum areas | Required minimum areas (international standards) | Fewer building costs; affordability |

| Optimization of housing layout | Passive solutions for cooling, ventilation, and natural light | Fewer energy consumption costs |

| Housing flexibility (expansion) | Household dimension and dynamic | Affordability; meeting household financial capacity |

| Centralization of service areas/Infrastructure | Infrastructure core | Reduced construction and maintenance costs |

| standardization | Prefabricated materials | Quality control; reduced construction and maintenance costs; affordability |

| Application of materials produced/extracted locally | Cost, quality, and performance | Reduced construction costs (labor and transport) |

| Assisted self-construction | Household/community skills and capacity | No costs related to specialized labor; Affordability |

| Multifunctional housing | Source of income | Wealth; Individual and collective development |

| Criteria | Parameter (s) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Construction on stilts | Location; Soil characteristics | Adequacy in local environmental conditions and natural risks |

| Optimization of housing layout | Passive solutions for cooling, ventilation, and natural light | Reduced energy consumption; Thermal comfort |

| Standardization | Prefabricated solutions | Resource management; Reduced waste; Optimization of energy consumption |

| Application of materials produced/extracted locally | Cost, quality, and performance | Reduced energy consumption; Thermal comfort |

| Centralization of service areas/Infrastructure | Infrastructure core | Resource management (less materials) |

The adaptive housing framework is structured in three areas: social, economic, and environment (Fig. 7 ). The main indicators for assessing the criteria and parameters are based on the standard-housing features (understanding them and making them adequate), local lifestyle (accommodating it in the new proposed houses), household characteristics, source of income, and bioclimatic features for both thermal comfort and durability.

|

|

|

Fig. 7. Framework for adaptive housing (example of the structure). |

The framework is presented in Table 1 , Table 2 ; Table 3 .

5.5. Housing projects

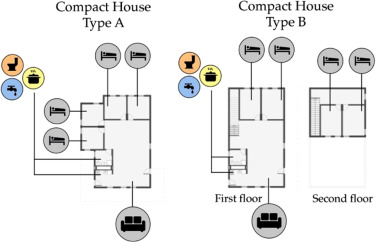

The implementation of the framework resulted in three standard projects to be applied in the Oé-Cusse Region. These standard projects cannot be perceived as restrictive but as an operative support within the assisted self-building scheme. The local technical team can work on these standard projects to support the population and to find the most suitable solution. All housing models are single-family units in accordance with the densities and zoning parameters defined in the regional plan.

Although the plot size might vary, a standard dimension of 500 m2 is considered (Fig. 8 ). An agricultural area between 2000 and 4400 m2 will be added if needed. The size of the agricultural area results from the average size of agricultural areas in the Oé-Cusse Region, and the average size of a family farm is based on the estimate by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. This standard dimension can accommodate the “multifunctional housing” criteria (Fig. 9 ), i.e., the source of income linked to the house, such as agriculture, small businesses, and workshops (pottery, weaving, and carpentry) without compromising public health.

|

|

|

Fig. 8. Compact housing: Types A and B. |

|

|

|

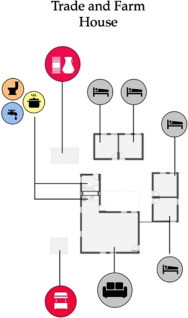

Fig. 9. Diagram of Trade and Farm House. |

The standard projects can be expanded from two-bedroom houses to four-bedroom houses. This allotment for an expansion is based on the average household size in the Oé-Cusse Region according to the 2010 Census (5.6 members per household) articulated under the international standard for overcrowding (≤3 people per bedroom). Thus, a two-bedroom housing core is considered to accommodate 6 people while ensuring that adults and children occupy different bedrooms.

These projects might be built on the ground or on stakes depending on the bioclimatic features and location.

These housing projects are structured in three variations: compact house, trade house, and farm house.

The first is developed for the urban area of Pante Macassar or any other location that envisages higher densities. This project follows an incremental scheme between two-bedroom and four-bedroom houses, and might include a second floor if necessary. For the envisaged density, this project might be materialized in semi-detached housing. The two-bedroom core includes a technical wall (infrastructure core) with a kitchen, a bathroom, a living room, and two bedrooms. The expansion is achieved simply by creating additional bedrooms.

Trade and farm units are more suitable for rural than urban areas, and these units include other functions, such as spaces for small businesses, workshops, and/or agriculture areas. This project is an interpretation of the current standard dwellings in Oé-Cusse. It integrates a central courtyard where daily life occurs through social gatherings and production (workshops). The expansion is implemented by adding bedrooms around the courtyard. This variation also has a small covered area at the front for selling, as is the case in the current model. In the case of the farm house, an agriculture area between 2000 and 4400 m2 is added to the 500 m2 housing plot.

In both of these variations, a passive design is implemented for cooling and cross ventilation. The minimum areas and the number of rooms, which depend on the household size, are considered to ensure a healthy environment. Multi-functionality is introduced to better accommodate the source of income while allowing self-development. The ability to incrementally expand is proposed and materialized by adding bedrooms (the expansion unit of the house). As mentioned, these projects are not restrictive solutions but only serve as basis for an adequate housing design. The local technical team must support the local initiatives.

6. Conclusions

Rural development has been neglected in developing countries. Majority of investments are targeted toward urban areas because of their economic importance, high poverty level, and precarious conditions. Consequently, a closed loop is formed because the absence of a development strategy for rural areas leads to migrations to urban centers, further aggravating the problem. Rural settlements become more isolated and the rural–urban continuum is compromised. Several approaches have been implemented in developing countries, such as site and service schemes and public–private partnerships, to solve the housing problem. However, in most cases, these schemes were aimed at specific social and economic objectives or only solved small parts of the larger problem. Therefore, an inclusive approach that includes several scales and phases is needed.

This paper discusses the development of an inclusive housing program for the Oé-Cusse Region within the regional plan created in 2016. This program is based on the idea of the house as a driver of rural development. This territory is marked by its geographic isolation from the rest of the national territory, lack of infrastructure, and precarious housing that results from past conflicts and political instability. Nonetheless, the self-determination of the population slowly supported the development of this special region. People built their own houses despite the lack of financial and material resources, and they created a small-community economy. The common element is the home where all daily activities occur. The house also reflects the local lifestyle and has a singular layout that demonstrates how various functions can be clearly separated but organized around a common space: the courtyard where the water source is located. The needs and potentials are the matrix for the strategy that can enable and promote sustainable development and contribute to poverty reduction.

A strategy based on a holistic approach that integrates all dimensions of human activity and impact is presented. The strategy considers the social, economic, and environmental context of the region to create an adequate and suitable solution. This inclusive housing program considers several scales from the policy level to the project scale. At the policy level, a partnership model including the regional authority, the private sector, and the population is proposed. This model clearly defines the role of each stakeholder. The public sector should create conditions for development and attract private investment through land and infrastructure provision, taking advantage of the self-determination aspect of the local population within an assisted self-building scheme. The private sector is responsible for urbanizing and developing a share of the affordable houses. These policies directly determine and influence decisions that are supported by guidelines and good practices to develop a framework for housing design. The framework consists of comprised criteria, parameters, and their outcomes at the social, economic, and environmental contexts. Standard projects are proposed not as restrictive solutions but as bases that can be adapted and developed with the assistance of the community supported by a local technical team specialized in self-building processes. The models of compact houses and multi-functional models accommodate different activities in the housing plot, such as small businesses, workshops, and/or agriculture.

The inclusive housing program considers three levels. The first refers to the policies that influence and determine decisions and actions. Policies provide legal support for implementing processes, partnership schemes, and the role of each stakeholder. The second level refers to the guidelines for sustainable settlement and housing development. The third level occurs at the building level at which the criteria and parameters for housing design and their outcomes are considered.

The inclusive housing program is a new approach to housing that uses the current local potential and features to provide a sustainable and effective solution in a context where the lack of resources and the absence of a structured governance network are a major constraints. The main premise is the idea of “doing more with less” in view of an adaptive and resilient response not only for the current needs but also for the future transformation of the territory and society of the Oé-Cusse Region. Self-determination of the population and a relative autonomy for the private sector are the main considerations.

For the main outcomes, the inclusive housing program will provide a viable solution for housing, where the financial efforts are shared not only between the public and private sectors but also with the population through a self-building and participatory scheme. This condition will result in the following economic and social outcomes: community involvement and self-building ensures adequacy, affordability, and opportunity (avoiding the closed loop of urban investment/rural migrations); public sector supports this process at the policy level and with land valorization, sharing the housing provision with the other stakeholders (private sector and population), thereby enabling them to focus on other investments (urbanization). At a different scale (as far as this strategy considers several scales), housing will provide not only a shelter but also wealth according to the current potential of the population and the local economic dynamic.

Further studies should monitor and evaluate the application of this approach during the implementation and use phases. If needed, the program should be adapted to the identified results.

References

- Abbott, 2002 John Abbott; A method-based planning framework for informal settlement upgrading.; Habitat Int., 26 (3) (2002), pp. 317–333 http://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(01)00050-9

- Akkar, 2006 Z.M. Akkar; The concepts, definitions and processes on urban regeneration in the Western literature and Turkey.; J. Chamb. City Plan., 36 (2006), pp. 29–38

- Sabina et al., 2014 Sabina Alkire, Mihika Chatterjee, Adriana Conconi, Suman Seth, Ana Vaz; Poverty in Rural and Urban Areas: direct Comparisons Using the Global MPI 2014 | OPHI; Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford (2014) 〈http://www.ophi.org.uk/poverty-in-rural-and-urban-areas/〉

- Amado, Miguel P, 2005 Amado, Miguel P, 2005. "Planeamento Urbano Sustentável" Edições Caleidoscopio, Casal de Cambra (in Portuguese )

- Amado and Ramalhete., 2015 Miguel P. Amado, Inês Ramalhete; Parametric elements to modular social housing.; Housing the Future: Alternative Approaches for Tomorrow, Libri Publishing, Liverpool (2015)

- Amado et al., 2016 Miguel P. Amado, Inês Ramalhete, António R. Amado, João C. Freitas; Regeneration of informal areas: an integrated approach.; Cities, 58 (2016), pp. 59–69 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.05.015

- André et al., 2012 Isabel André, André Carmo, Alexandre Abreu, Ana Estevens, Jorge Malheiros; Learning for and from the city: the role of education in urban social cohesion.; Belgeo (2012) http://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.8587

- Aravena and Iacobelli, 2013 Alejandro Aravena, Andres Iacobelli; Elemental: incremental Housing and Participatory Design Manual; Hatje Cantz, Berlin (2013)

- Basu, 1988 Ashok Ranjan Basu; Urban Squatter Housing in Third World; Mittal Publications (1988)

- Beattie et al., 2010 Beattie, N., Mayer, C., Yildirim, A., 2010. Incremental housing: solutions to meet the global urban housing challenge. In: Network Session – Global University Consortium – SIGUS-MIT. Rio de Janeiro. 〈http://web.mit.edu/〉 .

- Blaustein et al., 2014 Susan M. Blaustein, Victor Body-Lawson, Priscila Coli, Kirk Finkel, Petra Kempf, Geeta Mehta, Richard Plunz, Maria-Paola Sutto; Spatial strategies for Manyatta: designing for growth (1st ed), The Urban Design Lab at the Earth Institute of Columbia University, New York (2014)

- Bugalski, 2010a Natalie Bugalski; Post conflict housing reconstruction and the right to adequate housing in Timor-Leste: an analysis of the response to the crisis of 2006 and 2007.; Rep. the Hum. Rights Counc.׳S. Sixt. Sess. Post-Disaster Post-Confl. Situat. Asheville: Incl. Dev. Int (2010)

- Christiaensen and Todo, 2014 Luc Christiaensen, Yasuyuki Todo; Poverty Reduction During the Rural–Urban Transformation – The Role of the Missing Middle.; World Dev., 63 (2014), pp. 43–58 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.002

- Devas and Rakodi, 1994 Nick Devas, Carole Rakodi; Managing fast-growing; Urban Stud., 31 (2) (1994), pp. 336–337 http://doi.org/10.1080/00420989420080311

- Donaghy, 2013 Maureen M. Donaghy; Civil Society and Participatory Governance: Municipal Councils and Social Housing Programs in Brazil (1 edition), Routledge, New York, NY (2013)

- Fitzpatrick, 2012 Daniel Fitzpatrick; Land claims in East Timor: a preliminary assessment.; SSRN Electron. J (2012) http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2019775

- Gattoni, 2009 George Gattoni; A case for the incremental housing process in sites-and-services programs and comments on a new initiative in Guyana.; Global University Consortium Exploring Incremental Housing, Global Consortium for Incremental Housing, Rio de Janeiro (2009)

- Governo da República Democrática de Timor-Leste, 2011 Governo da República Democrática de Timor-Leste, 2011. Timor-Leste: Strategic Development Plan 2011–2030. Governo da República Democrática de Timor-Leste. 〈http://timor-leste.gov.tl〉 .

- Greene, Margarita, and Eduardo Rojas, 2008 Greene, Margarita, and Eduardo Rojas; Incremental construction: a strategy to facilitate access to housing.; Environ. Urban., 20 (1) (2008), pp. 89–108 http://doi.org/10.1177/0956247808089150

- Gunn, 1999 Geoffrey C. Gunn; Timor Loro Sae: 500 Years; Livros do Oriente, Macau (1999)

- Hearn, 2006 Fil Hearn; Ideas queue Han Configurado Edificios; Gustavo Gili, Barcelona (2006)

- Keivani et al., 2008 R. Keivani, M. Mattingly, H. Majedi; Public management of urban; Urban Stud., 45 (9) (2008), pp. 1825–1853 http://doi.org/10.1177/0042098008093380

- Keivani and Werna, 2001 R. Keivani, E. Werna; Modes of housing provision in developing countries.; Prog. Plan., 55 (2) (2001), pp. 65–118 http://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-9006(00)00022-2

- Lucas, 2011 Karen Lucas; Making the connections between transport disadvantage and the social exclusion of low income populations in the Tshwane Region of South Africa.; J. Transp. Geogr., 19 (6) (2011), pp. 1320–1334 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.02.007

- Massoud et al., 2009 May A. Massoud, Akram Tarhini, Joumana A. Nasr; Decentralized approaches to wastewater treatment and management: applicability in developing countries.; J. Environ. Manag., 90 (1) (2009), pp. 652–659 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.07.001

- McGill University, 2010 McGill University; Aranya Housing Project – Post-Occupancy Study of Aranya Housing Project: An Architecture for the Developing World; McGill University, Montreal, Canada (2010)

- MIT Center for Advanced MIT Center for Advanced Urbanism, 2016. Scaling Infrastructure, Princeton Architectural Press

- Moglia et al., 2010 Magnus Moglia, Pascal Perez, Stewart Burn; Modelling an urban water system on the edge of chaos.; Environ. Model. Softw., 25 (12) (2010), pp. 1528–1538 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.05.002

- Mukhija, 2004 Vinit Mukhija; The contradictions in enabling private developers of affordable housing: a cautionary case from Ahmedabad, India; Urban Stud., 41 (11) (2004), pp. 2231–2244 http://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000268438

- Native Energy Inc, 2012 Native Energy Inc, 2012. Kenya Clean Water Project. Burlington, VT, USA: Native Energy Inc.,

- Nijman, 2008 Jan Nijman; Against the odds: slum rehabilitation in neoliberal Mumbai; Cities, 25 (2) (2008), pp. 73–85 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2008.01.003

- Porter, 2002 Gina Porter; Living in a walking world: rural mobility and social equity issues in sub-Saharan Africa; World Dev., 30 (2) (2002), pp. 285–300 http://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00106-1

- Ramalhete et al., 2016 Inês Ramalhete, Miguel P. Amado, Hugo Farias; Criteria framework for the conception of an adaptive housing model for sub-Saharan African region; Housing the Future – Alternative Approaches For Tomorrow, Libri Publishing, Oxfordshire (2016) 〈https://www.academia.edu/16996288/Criteria_Framework_for_the_conception_of_an_adaptive_housing_model_for_sub-saharan_african_region〉

- Rapoport, 2003 Amos Rapoport; Cultura, Arquitectura Y Diseño; Barc.: Univ. Politèc. De. Catalunya (2003)

- Ray and Jain, 2014 Ray, C., Jain, R., 2014. Low Cost Emergency Water Purification Technologies: Integrated Water Security Series. 2nd ed. Elsevier Science & Technology, Oxford. 〈https://www.bookdepository.com/Low-Cost-Emergency-Water-Purification-Technologies-Ravi-Jain/9780124114654〉 .

- Reeves, 2013 Paul Reeves; Affordable and Social Housing; Policy and Practice, Routledge (2013)

- Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy, 2015 Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Daniel Hardy; Addressing poverty and inequality in the rural economy from a global perspective.; Appl. Geogr., 61 (July) (2015), pp. 11–23 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.02.005

- Rowe and Kan, 2014 Peter G. Rowe, Har Ye Kan; Urban Intensities; Contemporary Housing Types and Territories, Birkhäuser (2014)

- Satterthwaite, 2006 Satterthwaite, D., 2006. Outside the Large Cities: The Demographic Importance of Small Urban Centres and Large Villages in Africa, Asia and Latin America. International Institute for Environment and Development, London.

- Stallen and Chabannes, 1994 Melanie Stallen, Yves Chabannes; Potentials of prefabrication for self-help and mutual-aid housing in developing countries; Habitat Int., 18 (2) (1994), pp. 13–39

- Tacoli, 2003 C. Tacoli; The links between urban and rural development.; Environ. Urban., 15 (1) (2003), pp. 3–12 http://doi.org/10.1177/095624780301500111

- Cecilia, 1998 Cecilia Tacoli; Rural-urban interactions: a guide to the literature.; Environ. Urban., 10 (1) (1998), pp. 147–166

- United Nations, 2016 United Nations, 2016. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1. New York: United Nations, New York.

- Foundation and Doshi, 1989 Vastu-Shipla Foudation, 1989. Aranya Community Housing - Indore, India. Indore, India: The Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

- Wallis and Thu, 2013 Wallis, J., Thu, P., 2013. In Timor. a New House Does Not Make a Home. School of International, Political and Strategic Studies - ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.

- Ward and Shackleton, 2016 Catherine D. Ward, Charlie M. Shackleton; Natural Resource Use, Incomes, and Poverty Along the Rural–Urban Continuum of Two Medium-Sized, South African Towns.; World Dev., 78 (2016), pp. 80–93 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.025

- WaterAid, 2008 WaterAid; Assessment of Urine-Diverting EcoSan Toilets in Nepal; WaterAid, Nepal (2008)

- Wekesa et al., 2011 B.W. Wekesa, G.S. Steyn, F.A.O. (Fred) Otieno; A review of physical and socio-economic characteristics and intervention approaches of informal settlements.; Habitat Int., 35 (2) (2011), pp. 238–245 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.09.006

- Werna, 2001 Edmundo Werna; Shelter, employment and the informal city in the context of the present economic scene: implications for participatory Government.; Habitat Int., 25 (2) (2001), pp. 209–227 http://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(00)00018-7

- Yang et al., 2016 Ren Yang, Qian Xu, Hualou Long; Spatial distribution characteristics and optimized reconstruction analysis of China׳s rural settlements during the process of rapid urbanization.; J. Rural Stud. , June (2016) http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.05.013

- Zemni and Bogaert, 2011 Sami Zemni, Koenraad Bogaert; Urban renewal and social development in Morocco in an age of neoliberal government.; Rev. Afr. Political Econ., 38 (129) (2011), pp. 403–417 http://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2011.603180

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?