Abstract

This study analyses the presence of gender segregation in Spanish exporting firms. Both womens access to managerial positions (vertical segregation) and womens achievement of managerial roles that are socially associated with communal attributes (horizontal segregation) are tested. We argue that boundary-spanning (henceforth, boundary management) in export interfirm relationships benefits from relational and communal skills and therefore could not only offer an opportunity for women to gain access to management positions but also put them at risk of falling into a rut before achieving other control-based managerial roles. This empirical study examines the characteristics (personal and firm-level) of Spanish female managers in charge of export management through independent channels. A multivariate analysis has been performed to compare female managers with male managers both in boundary management and in the position of finance director, a control position closer to a socially stereotyped masculine role. The results show that women have slightly higher access to boundary management jobs than finance management jobs, as well as a significantly lower promotion time than male colleagues, but they also corroborate that there is a smaller percentage of women than men in any management positions, with female managers working in younger firms with fewer resources for export activity.

JEL classification

J16;M10

Keywords

Gender;Inter-organizational relationships;Boundary management;Externalized export channels;Vertical and horizontal segregation

1. Introduction

Following the question of whether organizations and occupations are gender-neutral or not, debate on access for women and men to managerial roles is a much-discussed but incomplete question in management literature (Acker, 1990; Acker, 1994 ; Lewis, 2014). From a classical feminism perspective, gender stereotypes are considered barriers for equal opportunities that affect women’ chances of rising in corporate executive hierarchies; as a result, women are excluded from opportunities related to managerial roles that are identified with ‘male’ characteristics (Schein, 2007). Most recently, post-feminism has moved the focus to the way women and feminine points of view are being included in contemporary organizations, giving value to the skills and leadership styles associated with feminine traits and raising the notion of feminine management (Kelan, 2008 ; Lewis, 2014). This discourse derives from a liberal feminism of ‘difference’ (in contrast to the original liberal feminism of (masculine) ‘sameness’), which considers the ways in which masculine and feminine traits in organizations can potentially complement each other (Calas, Smircich, & Bourne, 2007).

As women have increasingly moved into managerial positions, vertical and horizontal segregation has been densely reported by the literature. Several reasons have been identified to occupational segregation in management jobs. Because jobs are thought to be gender typified based on requisites that are believed to be gender-linked (Heilman, 1983 ; Heilman, 1995), different management styles have been identified with characteristics assigned to societal gender stereotypes1 (Calas and Smircich, 1993 ; Fletcher, 1994). The masculine norm has dominated much of the gendered management literature, which emphasizes the need for individuals to build a masculine identity to fit the organizational requirements of control, competition, leadership, or success orientation. Therefore, female managers confront the existence of these stereotypes, which generate a conflict between social expectations of female gender roles and the traditional managerial role, which is stereotyped as masculine.

In contrast to this masculine style of management, a new ideal of manager has emerged in recent years that enhances a range of abilities and skills socially associated with women such as empathy, affectivity, sensitivity or assistance (Adkins, 2001; Bruni et al., 2004; Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001; Kelan, 2008; Mueller and Dato-on, 2013 ; Rosener, 1990). Such a feminine management style is particularly welcomed in contemporary organizations that require less hierarchical and more flexible, intuitive, communicative, cooperative, and participative leaders to face markets in constant flux (Pounder and Coleman, 2002 ; Stelter, 2002).

As a result, the traditional masculine-stereotyped manager, based on hierarchical power and control, would be particularly adapted to intra-organizational management settings (Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell, & Ristikari, 2011). However, in current inter-organizational contexts, control and authority are not deemed hierarchical. In these contexts, boundary-spanning (henceforth, boundary management) is characterized by (1) direct involvement in managing the relationship with the partner, entailing intense and extensive ongoing interaction with staff and managers of the other party (Friedman & Podolny, 1992) and (2) serving as the interlocutor in the relationship (Luo, 2006), making decisions about operational and strategic issues. As a result, interfirm management gives primacy to flexibility, communication, mutual sacrifice, trust, relationship commitment, and the need to share information among partners as keys to the success of collaborative agreements (Sahin & Robinson, 2002). These attributes have been found to be closer to managerial traits that have been more commonly associated with women than men (Burke and Collins, 2001; Maxwell et al., 2007 ; Trinidad and Normore, 2005). However, to our knowledge, there is no empirical evidence that specifically analyses the influence of gender in accessing inter-organizational management positions.

Considering such a gap, this paper is intended to analyze the occupational vertical and horizontal segregation that is currently in place in Spanish organizations where both control-based and boundary management positions coexist. We have chosen the international inter-organizational context for three main reasons. Firstly, the role of gender in international trade has scarcely been explored (Orser, Spence, Riding, & Carrington, 2010), so results will provide a better understanding of the role of gender in export management, particularly in the SME context. Secondly, traditional export management, i.e., without attention to the direct management of a relationship with another independent company, has been largely considered a male occupation because it includes business strategy and sales responsibilities (Theodosiou & Katsikea, 2007) and demands skills traditionally considered masculine, such as high technical knowledge about product design, specifications, features, and manufacturing (Katsikea & Skarmeas, 2003); but before such a view, the inclusion of relational skills required to manage foreign interfirm relationships introduces a new dimension to the export management position, enhancing the suitability of a feminine style of management. Thirdly, export arrangements are among the most common inter-organizational relationships, a fact that could make this studys findings more generalizable to other positions in which interfirm relational skills are needed.

To analyze the impact of gender stereotypes when accessing managerial positions, we first compare womens access to both finance and boundary management positions. The former is a control-based post whereas the latter is analyzed regarding a particular type of inter-organizational relationship, namely, export management in firms exporting through independent channels. To identify potential causes of segregation, we examine (1) the characteristics of women and men in management positions, specifically education and experience and (2) the features of their companies, specifically firm age, firm export experience, and the size of the teams engaged in export activities. Our quantitative analysis is based on an online questionnaire administered to SMEs located in Andalusia (Spain) that export regularly and employ independent channels. In our main findings, we observe that women face vertical segregation but also exhibit some characteristics than suggest horizontal segregation. While facing a significantly lower admission to any management jobs, women exhibit slightly greater access to boundary management positions than to finance director positions, have a shorter promotion time to export management than their male colleagues, but manage smaller teams than men do and exhibit less experience in export activities.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The theoretical framework is presented in Section 1, including a literature review of gender segregation in management positions; research hypotheses are developed building on a Social-Role Theory point of view. Section 2 includes the methodological approach followed in our empirical study. In Section 3, univariate and multivariate results are discussed. Conclusions and research limitations are summarized in Section 4.

2. Theoretical framework

Given the controversial debate on the interactions between gender, gender role orientations, and management styles, we use Social Role Theory as a framework (Eagly, 1987). This theory postulates that while managers’ behaviour is primarily affected by their formal organizational role, gender affects them in two ways that promote segregation: on the one hand, people react to managers in terms of social gendered expectations; on the other, managers have internalized gender roles that affect their own behaviour in organizational settings (Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001; Eagly and Wood, 2012 ; Eagly et al., 2000). As a result, we postulate that the ‘think manager, think male’ association is still embedded in organizational structures, which is detrimental to women accessing any management role and leads to vertical segregation. Vertical segregation or ‘glass ceiling’ refers to difficulties of women in accessing top senior positions in the management hierarchy, leaving them stuck in lower managerial levels than men (Instituto de la Mujer, 2008; ISOTES, 2012; Lyness and Heilman, 2006 ; Thornton, 2012). Moreover, the relational attributes associated with boundary management could increase women’ access and promotion to these sorts of managerial jobs compared to intrafirm positions related to hierarchical power and control, which leads to horizontal segregation. Horizontal segregation has also been reported, particularly in large firms where control-based management jobs are held by men, while women are stuck in administrative posts and face barriers to moving laterally into more powerful managerial positions; this point could be of a particular significance because experience in such control-based, powerful positions could be key for advancing to the senior jobs that feed vertical segregation (Blau et al., 2002 ; Lyness and Heilman, 2006). Finally, gender segregation is expected to be particularly entrenched when the firm is more consolidated and larger (Berenguer, Cerver, de la Torre, & Torcal, 2004).

2.1. Gender influence on management styles

Managers play organizational roles defined by their hierarchical position in the firm but simultaneously behave under the constraints of their socially based gender. As a result, the influence of gender in management is usually discussed in terms of the congruency, or lack thereof, between leadership styles and gender roles (Eagly and Johnson, 1990 ; Eagly et al., 2003). Because each individual adopts a gender-role orientation2 that exhibits a higher heterogeneity based purely on sex differences (Gupta et al., 2009; Mueller and Dato-on, 2008; Mueller and Dato-on, 2013 ; Watson and Newby, 2005), men and women could mobilize both masculine (agentic) and feminine (communal) traits when managing businesses even if empirical research suggests women are more likely to adopt feminine gender roles than men, particularly in Spanish samples (Mueller and Dato-on, 2013 ; Pérez-Quintana and Hormiga, 2015).

Leadership styles refer to patterns of behaviour displayed by managers and can be classified under multiple scales. Authors such as Bales (1950) or Stogdill (1963) distinguished between a task-oriented style, which adopts task accomplishment based on organizing and assigning relevant activities, and an interpersonally oriented style, which adopts a social welfare concern based on maintaining interpersonal relationships. Later, a democratic/participative style vs. autocratic/directive style of management was adopted as focus of gender research (e.g., Eagly and Johnson, 1990 ; Vroom and Yetton, 1973); managers following a participative style are expected to allow subordinates to participate in decision making processes but those following a directive style are expected to discourage such participation. More recently, three modes of leadership have been identified in contemporary business based on the relationship between the leader and subordinates: transactional, transformational and laissez-faire styles (Bass, 1998 ; Burns, 1978). Transactional managers establish relationships with subordinates based on clarifying responsibilities, monitoring tasks, and establishing an objective-based rewarding policy; also known as ‘management by exception’ style, managers act only in the case of problems to adopt corrective measures. In contrast, transformational managers focus on mentoring subordinates to develop their potential to contribute to the full organization by establishing high-standards of behaviour and building trust; it considers motivation and creativity as key forces in management.3

Gender roles refer to the stereotypes that people have about the behaviour of women and men according their sex. They are based on the distinction between agentic and communal attributes (Eagly et al., 2000). Agentic characteristics are attributed more strongly to men than women and include traits such as assertiveness, control, and confidence, leading to aggressive, ambitious, dominant, independent, competitive and self-confident behaviour. In management settings, it would match with a problem-focused behaviour of the manager based on task assignation, competing for attention, speaking aggressively, or looking to influence others (Eagly & Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001). Communal attributes are attributed more strongly to women than men, including aspects such as interpersonal affectivity, empathy, kindness, sensitivity and assistance. In management settings, it would match with a relational-focused behaviour of the manager that was based on speaking cautiously, sharing attention, and supporting others (Eagly & Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001).

Correspondence of leadership styles and gender roles has been deeply researched with contradictory results about whether the question of management style is gender stereotypic or depends on the formal position in the organization (for literature reviews see Eagly and Johnson, 1990 ; Eagly et al., 2003). Social psychological researchers claim that women and men have distinctive management styles, which would be reflected in management skills such as communication, leadership, negotiation, organization and control (Claes, 1999). As a result, female managers have been reported to be less hierarchical, more collaborative, and more concerned about others’ welfare than male managers (Book, 2000 ; Helgesen, 1990), which matches with a more democratic, interpersonally oriented, and transformational style of management than men. In contrast, social structural researchers maintain that there are no significant differences in the management styles of women and men (Powell, 1990); because male and female managers occupying equivalent positions have been selected based on the same organizational criteria and provided with clear guidelines for managing effectively, no significant differences should be found in their management style.

As the most balanced approach, we adopt the Social-Role Theory that postulates that the influence of both gender and organizational roles in management styles is due to cultural expectations for the appropriate conduct of managers (Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001 ; Moskowitz et al., 1994). While managers are expected to carry out specific activities and conform to norms in their organizational role with independence from their gender, they also have some freedom about the way to carry out these requirements in which gender socialization processes could play a role. As a result, womens managerial behaviour would be influenced by the organizational role being played but also by sex differences experienced through life (internalized gender roles) along with peoples expectations of their behaviour based on their socially identified sex (Eagly et al., 2000). Thus, women could play different femininities when managing firms (Lewis, 2014), including the individualized entrepreneurial one, characterized by a distancing from the traits of traditional femininity and an adoption of classical (masculine) traits, as well as the relational one, which promotes a more empathetic, mutually empowered way of doing business.4 These arguments are agreed with particular evidence on the behaviour of Spanish female managers, who are observed to share some attributes with men (e.g., being competitive, creative, resolute, efficient in solving problems, communicative), but still score higher in communal characteristics in terms of being more participative, empathetic, flexible, democratic, collaborative and more focused on interpersonal relationships than men (Barbera et al., 2000; Berenguer et al., 2004 ; Charlo and Núñez, 2012).

2.2. Gender segregation in managerial positions

Because gender can foster different expectations of management styles, it could lead to incongruences between social demands of the female gender role and the traditional manager role; the higher this incongruence is, the smaller the access and promotion of women to managerial positions (Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001; Eagly et al., 2003 ; Lyness and Heilman, 2006). Moreover, evidence shows that women and men typically prioritize work and family roles differently (Chuang, 2010; ILO, 2004; Jennings and McDougald, 2007 ; OECD, 2011). In Spain specifically, women have traditionally served as caregivers and domestic workers and are willing to make greater sacrifices of job performance to family life than men (Iglesias & Llorente, 2008), which affects their chances of accessing top-managerial positions because of the lack of work–family life balance (Barbera et al., 2000).

Consequently, there is significant evidence of vertical gender segregation in managerial positions. Bingham and Quigley (1995) report that, in the United States, women occupy only 21% of sales management positions, whereas Solomon (1998) reports just 13–14% of international assignments go to women. In Spain, the report by ISOTES (2012) indicates that the proportion of women in commercial/sales management positions is only 10%. In line with previous data, the finance director position also seems to be more likely held by a man than a woman (according to ISOTES, 2012, 83% vs. 17%, respectively). Therefore, we postulate the presence of vertical segregation in managerial positions of Spanish exporting firms, as follows:

H1.

The percentage of women performing the managerial role is lower than the percentage of men in both finance and boundary management.

As factors that could impact on vertical segregation, both educational background and experiential profile must be analyzed (Bingham & Quigley, 1995). Educational background is considered of great importance for accessing management positions in general and export activity in particular (Leonidou et al., 1998 ; Wayne et al., 1999). However, while not being conclusive, literature on career development has established differences in the paths to managerial career success related to educational level. Authors such as Stroh, Brett, and Reilly (1992), Tharenou, Latimer, and Conroy (1994) or Eddleston, Baldridge, and Veiga (2004) find education to benefit mens career more than womens in managerial advancement. Along the same lines, Liff, Worrall, and Cooper (1997) find that women are slightly more educated than men, although they hold a lower percentage of managerial positions. A similar situation is observed in Spain, as reported by Charlo and Núñez (2012); additionally, the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sports reports that during the academic year 2013–2014, 54.4% of students enrolled in the Spanish university system were women, a slight increase since 1998–1999 when the percentage was 53.3%.5 These data show that in the last 15 years women have had greater access to higher education than men; in 2012–2013, 57.3% of students who completed university studies were women. In 2014, the percentage of employed women with higher education was 46.6%, while the corresponding percentage for men was 38.2%. However, this situation has not produced higher wages, greater access to decision-making positions, or greater job stability for women (Instituto de la Mujer, 2007). According to data for 2014, in Andalusia 7.3% of employed men with higher education and doctoral degrees were managers, but in the case of women, the corresponding percentage was less than half, only 3.2%, although the total number of employed women with such academic degrees was 103.6% of the number for men.6 Thus we predict that,

H2a.

The average educational level of female managers is higher than the average educational level of male ones.

Given that explicit or articulable knowledge acquired through formal education is a crucial resource for competitive advantage, male managers’ relatively lower education could cut into management efficiency and business performance. However, we must also take into account that tacit knowledge gained by experience can improve performance (Hitt, Bierman, Shimizu, & Kochlar, 2001). Time spent performing the same or similar activities or working in the same sector can be considered a proxy for experience, making up for any deficiencies in academic background or strengthening it, and therefore, companies may promote or keep people with more experience (Stroh et al., 1992).

However, the literature has reported differences in career development in terms of tenure, with mens work management experience being reported to be more highly valued than womens (Kirchmeyer, 2002). In this line, Bingham and Quigley (1995) find that female managers have less experience than male ones in sales and management and usually have less time in the firm. Liff et al. (1997) note that, when women are asked about their highest level of education, they list degrees, while men cite professional qualifications. Finally, a larger proportion of women have entered the Spanish labour market only in recent decades, so they have less experience than men, which is a situation that should be corrected in the future (Barbera et al., 2000). Therefore, we predict that

H2b.

The average experience in managerial activities of women is lower than the average experience of men.

H2c.

The female managers’ average experience in the industry is lower than the average experience of male managers.

However, horizontal segregation could also emerge as a result of role congruity because managerial supporting functions are closer to the communal qualities that are associated with women, while technical managerial functions are nearer to the agentic qualities that people identify with men. Moreover, if female managers have interiorized gender-stereotypic expectations, they might gain self-confidence in their capability for leadership in positions that require a more democratic, transformational style of behaviour while avoiding other managerial positions characterized by a higher level of control and competitiveness (Barbera et al., 2000; Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001 ; Eagly et al., 2003). Along these lines, Berenguer et al. (2004) report managers have a general perception of women playing a more protective role towards employees than men, while men achieve a higher cohesion of workers. Such perception is particularly strong among female managers who define themselves as more flexible, protective, charming, and with a higher capacity for solving conflicts and delegating than masculine colleagues. Other studies, including those by the ILO (2004), Lyness and Schrader (2006), Guillaume and Pochic (2009), Charlo and Núñez (2012) and ISOTES (2012), report women getting positions in administration or supporting functions (e.g., marketing or human resources), while men occupy more technical and operational posts. The report prepared by Thornton (2012) explicitly states that, in senior management positions, women are better represented in human resources jobs. In Spain, the Instituto de la Mujer (2008) reports that positions related to strategy are more likely to be occupied by men (28.3% of male managers) than by women (9.8% of female managers), who are engaged mainly in administrative responsibilities (12.1% of female managers vs. 5.4% of male managers) and human resources (12.9% vs. 8.0%).

The export manager position requires different abilities, including not only market skills but also relational skills to manage relationships with foreign intermediary businesses (Kaleka, 2002 ; Piercy et al., 2003). Firstly, the export manager has to assume the responsibility and risks of internationalization, requiring a high level of expertise and customer orientation to achieve good export performance in increasingly uncertain markets (Katsikea and Skarmeas, 2003 ; Morgan et al., 2004). Secondly, people in charge of exporting are in permanent contact with staff and managers of foreign intermediary companies as well as their own export team; managing the relationship with the intermediary business is hampered by greater psychic distance (Bello, Chelariu, & Zhang, 2003), so the person responsible for exports must have high social, relational, and communication abilities (Williams & Chaston, 2004).

As far as market skills are concerned, Chang, Polsa, and Chen (2003) show that a participatory and supportive management style can enhance the customer orientation to the marketing channel and thus performance, while autocratic styles can avoid it. Regarding relational skills, cultural sensitivity of the people responsible for international sales can improve relations between buyer and seller (Harich & LaBahn, 1998). Along these lines, Katsikeas, Skarmeas, and Katsikea (2000) and Bello et al. (2003) argue that the development by the exporting company of norms of flexibility, solidarity, mutuality, commitment and information exchange encourage relationships with intermediaries, improving export performance. Similarly, Doole, Grimes, and Demack (2006) note in their study of SMEs that relational and networking abilities are critical to enhancing exporting capacity. As a result, export relationships have been found to achieve a higher performance when managed using a social management control system characterized by interpersonal interactions between partners (Flórez et al., 2012). In sales management, some findings suggest that men pursue a more behaviour-control oriented approach than women, who are characterized by a higher proactive discussion, participative training, intrinsic motivation, and interpersonal relationships (Piercy, Cravens, & Lane, 2001). Moreover, management literature proposes that women are more democratic and oriented towards interpersonal relationships than men and have a perception about the world that gives more importance to social relations and networks (e.g., Burke and Collins, 2001 ; Linstead et al., 2005). As a result, a feminine gender-role orientation could be found as particularly suitable to the characteristics which are socially expected for the position of boundary manager, and therefore gendered expectancies could encourage (i) a greater access and (ii) a quicker promotion for women to inter-organizational managerial positions than to other posts (Eagly & Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001). The above arguments lead us to propose that,

H3.

The percentage of women performing the export boundary manager role is higher than the percentage of women performing the finance director role.

H4a.

The average time for promotion of women performing the export boundary manager role is lower than the average time for promotion of women performing the finance director role.

H4b.

The average time for promotion of female export boundary managers is lower than the average time for promotion of male ones.

2.3. Features of firms with female vs. male boundary managers

Women may encounter more barriers to hiring and promotion in large firms, characterized by a more hierarchical, masculine-based style of management. In Spain, according to data for 2009, 23.8% of managers in companies with 10 or more employees are women, a figure that rises to 30.3% for firms with fewer than 10 employees, and almost 45.7% for firms without employees. Cliff (1998) argues that female owners tend to set limits for the growth of their companies. Empirical studies on Spanish SMEs (Berenguer et al., 2004; Díaz and Jiménez, 2010 ; García et al., 2012) suggest that companies being run by women are smaller than those run by men. Moreover, the ILO (2004) has noted that women often prefer to devote their efforts and know-how to more flexible (but smaller) organizations or to start their own businesses. Because boundary export management usually involves managing a team, the desired flexibility can be achieved, inter alia, by means of a small team. In this line, Charlo and Núñez (2012) find Spanish female managers lead significantly smaller teams than men, which is also as a consequence of working in smaller organizations. Thus, there may be a negative association between the size of export teams (also a proxy of firm size) and gender, so we formulate the following hypothesis,

H5.

The number of employees engaged in export activities in firms where women are managing export boundaries is lower than in companies where men are playing this role.

Although García et al. (2012) found no significant differences in firm age between men and women in SMEs, other studies have found that more consolidated Spanish companies have more women in positions requiring high qualifications (Ministerio de Sanidad & Política Social e Igualdad, 2011). Analysing Spanish boards of directors, the Instituto de la Mujer (2008) finds that there is a correlation between the oldest companies and women directors. De Cabo, Gimeno, and Escot (2010) also show that the oldest Spanish companies have more women on boards of directors and argue that firms that discriminate against women have worse long-term performance and survival probability because they are less efficient than those firms that do not discriminate by gender. If the same logic of efficiency applies to export boundary management, then we argue that the greater the age of the company, both since its founding and since the beginning of its export venture, the more likely that the company has hired women in the position:

H6a.

The average age of firms with female export boundary managers is higher than the average age of companies with male ones.

H6b.

The average experience in export activities of firms with female export boundary managers is higher than the average experience of companies with male ones.

3. Methods

We designed an online questionnaire based on the methodology proposed by Dillman (2000) and submitted it to people in charge of export and finance activities in Andalusian firms that export regularly through externalized channels. The population was composed of 656 firms identified by means of a database provided by EXTENDA, an Andalusian public agency that supports internationalization. We obtained 193 valid questionnaires from export managers (29.42%) and 85 from finance directors (12.96%). Due to differences in response rates between both groups, a Fisher-exact test was performed to compare both finance-manager and export-manager samples; results confirmed significant differences between the two response rates (p-value < 0.05), so generalization of group-comparison results should be taken with caution. The response rate of each management group was closely similar to or even over those from previous export management literature,7 allowing us to assume the reliability of each individual sample.

In addition to the respondents gender, the questionnaire asked for information on the characteristics of the person in the post (formal education in terms of academic degree, time working in the firm, time working in the industry, time working in the current position, and experience in export activities) and the features of the firm (relative size of export team in relation to competitors, time engaged in the main industry, and experience in export activities). Table 1 summarizes the main descriptive statistics.

| Boundary managers | Finance directors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Difference | Women | Men | Difference | |

| Total respondents (% over total number) | 42 | 151 | 17 | 68 | ||

| 21.76% | 78.24% | 56.48% | 20.00% | 80.00% | 60.00% | |

| Personal characteristics | ||||||

| Formal education/academic degree (% over total number of women or men) | ||||||

| Primary education | 0.00% | 2.65% | −2.65% | 0.00% | 2.94% | −2.94% |

| Secondary education | 21.43% | 20.53% | 0.90% | 17.65% | 22.06% | −4.41% |

| Higher education: Diplomatura (3-years degree) or equivalent | 26.19% | 21.85% | 4.34% | 35.29% | 17.65% | 17.64% |

| Higher education: Licenciatura (5-years degree) or equivalent | 47.62% | 50.99% | −3.37% | 41.18% | 52.94% | −11.76% |

| Average experience in export/finance activities (standard deviation) | 6.94 years (6.40) | 9.96 years (7.95) | −3.02 years | 6.75 years (5.05) | 7.94 years (6.26) | −1.19 years |

| Average time in the industry (standard deviation) | 8.42 years (7.97) | 12.05 years (9.00) | −3.63 years | 9.22 years (5.35) | 11.17 years (8.23) | −1.95 years |

| Average time working in the firm (standard deviation) | 5.42 years (4.59) | 9.98 years (8.34) | −4.56 years | 6.32 years (5.60) | 8.47 years (7.92) | −2.15 years |

| Average time in the position (standard deviation) | 4.15 years (4.03) | 7.75 years (6.68) | −3.60 years | 4.97 years (4.33) | 7.24 years (6.44) | −3.60 years |

| Average lag between entry into the company and promotion | 1.27 years | 2.23 years | −0.96 years | 1.35 years | 1.23 years | 0.12 years |

| Firm-level characteristics | ||||||

| Export team sizea | 2.87 | 3.35 | −0.48 | 3.64 | 3.64 | 0.00 |

| Average time of the firm in the main industry (standard deviation) | 27.85 years (27.74) | 33.50 years (43.07)b | −5.65 years | 25.50 years (27.52)b | 31.83 years (44.19)b | −6.33 years |

| Average experience of the firm in export activities (standard deviation) | 9.39 years (7.78) | 20.39 years (36.86)b | −11.00 years | 7.69 years (5.17) | 20.61 years (33.34)b | −12.92 years |

a. Managers were asked whether the number of full-time employees devoted to export activities was lower than, equal to, or higher than the number at the companys main competitors. Answers were measured on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Much lower) to 7 (Much higher) with the mean value being 4 (Equal).

b. The presence of a standard deviation above the average is due to the existence of a high dispersion and asymmetry in the data distribution, so the mean is not considered as representative of the distribution (Pearson variation coefficient > 1). In this case, the means equality test is not appropriate to analyze the differences between samples.

4. Results

4.1. Womens access to management roles in export firms. A univariate study

A simple analysis of percentages reveals significant differences in the level of access for men and women to managerial roles (Table 1), suggesting the presence of vertical segregation in the sample of exporting firms (H1). In particular, 80% of finance directors and 78.24% of export managers were men compared to 20% and 21.76% of women, respectively. These data show that in Andalusia the percentage of women in export management through intermediaries is similar to sales managers’ data in the U.S. (Bingham & Quigley, 1995) but higher than in Spain (ISOTES, 2012). A Fisher-exact test was run to test if proportions of women and men were the same; as expected, results rejected the gender parity hypothesis for both samples (p-value < 0.05), so the proportion of men is found to be statistically higher than the proportion of women for both the finance director and export manager positions (p-value < 0.05).

The presence of horizontal segregation was also tested using a Fisher-exact test (H3); while descriptive data showed a slightly higher percentage of women in boundary management positions than in finance ones (1.76%), such a difference was not found as statistically significant (p-value > 0.05); thus, even if there is some evidence of the higher presence of female managers in the boundary management position, which requires more intense relational attributes than the financial job, H3 cannot be confirmed. However, if no percentage differences can be confirmed, the analysis of personal and firm characteristics associated to each position (boundary vs. finance management) could provide a more realistic view of potential gender differences between managers in each role.

4.1.1. Personal characteristics

To obtain a deeper understanding of segregation in Spanish exporting firms, we examined differences in the highest academic degree attained (H2a), experience in export activities (H2b) and experience in the industry (H2c) for female and male managers. Moreover, we compared time in the firm and time in the position between export managers and financial directors for women and men to search for reasons of potential differences in managerial promotion due to horizontal segregation (H4).8 Nonparametric tests of equality of means (Mann–Whitney U test) and equality of medians were used to test previous hypotheses ( Table 2).

| Gender-based comparison of boundary managers and finance directors | Comparison between boundary managers and finance directors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender-based differences (boundary managers) | Gender-based differences (finance directors) | Boundary managers vs. finance directors (women) | Boundary managers vs. finance directors (men) | |||||

| Mann–Whitney test p-value | Median test (non-parametric) p-value | Mann–Whitney test p-value | Median test (non-parametric) p-value | Mann–Whitney test p-value | Median test (non-parametric) p-value | Mann–Whitney test p-value | Median test (non-parametric) p-value | |

| Personal characteristics | ||||||||

| Formal education | 0.070 (0.944) | n.a. | 0.295 (0.768) | n.a. | 0.496 (0.620) | 0.088 (0.767) | 0.373 (0.709) | n.a. |

| Experience in export/finance activities | 2.518 (0.012)* | 3.320 (0.068)+ | 0.643 (0.520) | 0.007 (0.936) | −0.182 (0.855) | 0.010 (0.920) | 1.690 (0.093)+ | 1.412 (0.234) |

| Time in industry | 2.603 (0.010)* | 3.476 (0.062)+ | 0.572 (0.657) | 0.078 (0.780) | −1.050 (0.294) | 3.049 (0.081)+ | 0.434 (0.665) | 0.003 (0.954) |

| Time working in the firm | 3.369 (0.001)** | 2.729 (0.099)+ | 0.766 (0.444) | 0.029 (0.865) | −0.652 (0.515) | 0.310 (0.578) | 1.328 (0.184) | 1.013 (0.314) |

| Time in the position | 3.803 (0.001)** | 6.018 (0.014)* | 1.202 (0.229) | 3.098 (0.078)+ | −1.045 (0.296) | 0.018 (0.892) | 0.635 (0.525) | 0.019 (0.917) |

| Lag between entry into the company and promotion | 0.284 (0.776) | 0.009 (0.923) | 0.380 (0.704) | 0.000 (0.986) | 0.706 (0.480) | 0.109 (0.741) | 0.745 (0.456) | 0.036 (0.849) |

| Firm-level characteristics | ||||||||

| Export team size | 1.677 (0.094)+ | 0.543 (0.461) | −0.358 (0.720) | 3.265 (0.071)+ | −1.684 (0.093)+ | 1.248 (0.264) | −0.154 (0.125) | 0.005 (0.942) |

| Time of the firm in the main industry | 0.077 (0.939) | 0.010 (0.920) | 0.699 (0.484) | 0.028 (0.867) | 0.627 (0.531) | 0.088 (0.767) | 0.129 (0.897) | 0.223 (0.637) |

| Experience of the firm in export activities | 1.830 (0.067)+ | 2.002 (0.157) | 1.952 (0.050)* | 0.912 (0.340) | 0.355 (0.723) | 0.216 (0.642) | −0.660 (0.509) | 0.387 (0.534) |

- . p < 0.05.

- . p < 0.01.

+. p < 0.10.

n.a., not available; Stata 11.1 software.

Results show no significant gender differences in formal education (p-value > 0.05) for either boundary managers or finance managers; thus hypothesis H2a was rejected. Additionally, the comparative univariate analysis indicated no statistically significant differences in formal education (p-value > 0.05) between women in export management and women in finance direction positions.

However, the univariate analysis shows that men have more export experience than women, with an average difference of 3.02 years, being 95% statistically significant (H2b).9 Similarly, the analysis of the time of experience in the industry (H2c) shows a strong significant difference of 3.63 years between male export directors and female ones (p < 0.01). In the case of finance managers, such a gender difference is reduced to a statistically non-significant 1.95 years. Moreover, analysis showed no differences in within-sector experience between women in export management and women in finance direction, suggesting the shorter experience of women in the industry is common to any managerial position. Finally, a slightly significant difference in experience is observed between export and finance managers for men but not for women (p-value < 0.1): while men in export management average 9.96 years of experience, men in finance management average 7.94 years. This difference might suggest that export management requires more abilities associated with experience in similar activities than finance management does, even if no statistically significant differences were observed in the case of women; it might also imply that finance management positions have more rotation for men (promotion within the firm or expectation of higher salary in other firms) than export management positions.

Regarding H4, female export managers were found to have a lower time in the firm than men (average difference of 4.56 years, p-value < 0.01), as well as significantly lower average experience in export direction (3.60 years of difference in average, p-value < 0.01). Such results corroborate that male managers gained positions in the company as export directors before female managers did, a situation that initially could be attributed to the late incorporation of women into the management market in Spain. However, further analysis reveals that the average lag for women between entry into the company and promotion into the boundary managerial position is 1.27 years (see Table 1), almost one year less than the average time required by men (2.23 years). Even if such a difference is not statistically significant at 95%, it could be interpreted in terms that the rising awareness of Spanish firms and society about the need to eradicate gender-based differences has favoured faster promotion for female managers in recent years, both in the export and finance roles (female intra-position differences not being statistically significant, H4b is not supported). However, the quite different lag pattern for male and female finance directors (1.23 vs. 1.35 years, respectively) suggests two other likely explanations: (i) on the one hand, vertical segregation in export activities may have acted as a filter, allowing access only to specially qualified women who have been promoted faster; (ii) on the other hand, the socially ascribed characteristics of boundary management, linked to communal attributes, might have favoured faster promotion of women compared to men than in other managerial roles.

4.1.2. Firm-level features

Regarding the intensity of human resources devoted to export (H5), on a scale running from 1 (my export team is much smaller than our main competitors’ teams) to 7 (my team is much larger than our competitors’ teams), both male (3.34) and female (2.89) managers perceived that they were at a staffing disadvantage vis-à-vis their competitors (a score of 4 would have indicated equality). The gender difference being slightly significant (p-value < 0.1) suggests that women do manage smaller export teams than male managers. This difference may be due either to womens search for flexibility or to the fact that they work on smaller firms and thus are assigned fewer human resources than men.

About the companys experience in the main industry (H6a) and in export activities (H6b), the high dispersion of the data has reduced the reliability of the univariate test. However, a descriptive analysis suggests that, contrary to predictions in H6a and H6b, men work in older firms than women (p < 0.05), which are also slightly more experienced in export activities10 (p-value < 0.1). One explanation of such a connection between gender and firm experience could be that firms with a longer export tradition value experienced staff more than newer export companies do and therefore prefer male managers. Another likely explanation has to do less with efficiency and more with culture because export management is one of the areas most influenced by tradition and inertia (Huerta & García, 2006). Older firms may be subject to more traditional values and beliefs that prevent or hinder womens access to jobs in export management, both because these firms were founded in times less favourable for women and because their organizational practices, reproduced over time, are considered legitimate and necessary for survival.

4.2. Gender impact on boundary export management. A multivariate study

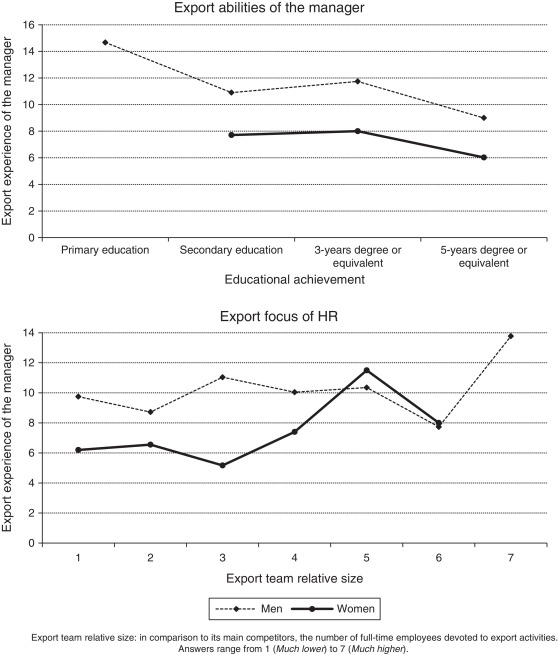

To obtain a more complete view of gender impact in boundary export management, we performed a hierarchical logistic regression analysis whose dependent variable was the male (0) or female (1) gender of the export manager. The independent variables were added in three successive stages to achieve a more stable model and to reduce problems related to multicollinearity (Orser et al., 2010). In the first and second stages, personal and firm-level factors were, respectively, included, while interactions between personal and/or firm-level factors were added in the third stage: export abilities of the manager (formal education × experience in export activities); overall experience in the industry (time of the manager in the industry × time of the firm in the main industry); overall export experience (experience of the manager in export activities × experience of the firm in export activities); export focus of human resources (export team size × experience of the manager in export activities); and firms experiential knowledge (experience of the firm in export activities × time of the firm in the main industry11). The results in Table 3 show a comprehensive picture of the causes of observed gender differences in access to boundary management.

| Base model: personal variables | Extended model (1): firm-level variables | Extended model (2): interactions among personal and firm-level variables | Final model | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | Standard error | p-Value | eb | b | Standard error | p-Value | eb | b | Standard error | p-Value | eb | b | Standard error | p-Value | eb | |

| Formal education | −0.176 | 0.162 | 0.277 | 0.838 | ||||||||||||

| Personal experience (time) in the firm | −0.102 | 0.035 | 0.004 | 0.903 | −0.058 | 0.030 | 0.049 | 0.943 | −0.111 | 0.033 | 0.001 | 0.895 | −0.124 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.884 |

| Personal experience (time) in the position | −0.081 | 0.041 | 0.048 | 0.922 | −0.072 | 0.037 | 0.052 | 0.930 | ||||||||

| Personal experience (time) in the industry | 0.049 | 0.026 | 0.062 | 1.050 | ||||||||||||

| Personal experience in export activities | −0.017 | 0.023 | 0.449 | 0.983 | ||||||||||||

| Constant | 1.564 | 0.632 | 0.013 | |||||||||||||

| Time of the firm in the main industry | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.065 | 1.010 | ||||||||||||

| Experience of the firm in export activities | −0.030 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.971 | 0.005 | 0.017 | 0.793 | 1.005 | ||||||||

| Export team size | −0.189 | 0.0889 | 0.032 | 0.827 | −0.490 | 0.148 | 0.001 | 0.613 | −0.476 | 0.133 | 0.000 | 0.621 | ||||

| Constant | 1.654 | 0.365 | 0.000 | |||||||||||||

| Export abilities of the manager (formal education × experience in export activities) | −0.029 | 0.013 | 0.022 | 0.971 | −0.033 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.968 | ||||||||

| Overall experience in the industry (time of the manager in the industry × time of the firm in the main industry) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.691 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Overall export experience (Experience of the manager in export activities × experience of the firm in export activities) | −0.003 | 0.001 | 0.271 | 0.997 | ||||||||||||

| Export focus of HR (export team size × experience of the manager in export activities) | 0.035 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 1.036 | 0.028 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 1.023 | ||||||||

| Firms experiential knowledge (experience of the firm in export activities × time of the firm in the main industry) | −0.464 | 0.422 | 0.271 | 0.629 | ||||||||||||

| Constant | 2.766 | 0.549 | 0.000 | |||||||||||||

| R2 McFadden: 0.091R2 Cox-Snell: 0.118R2 Nagelkerke: 0.157 Overall signif. (Omnibus) p: 0.000 | R2 McFadden: 0.130R2 Cox: 0.165R2 Nagelkerke: 0.220 Overall signif. (Omnibus) p: 0.000 | R2 McFadden: 0.134R2 Cox: 0.170R2 Nagelkerke: 0.226 Overall signif. (Omnibus) p: 0.000 | R2 McFadden: 0.112R2 Cox: 0.143R2 Nagelkerke: 0.191 Overall signif. (Omnibus) p: 0.000 | |||||||||||||

Note: A value odd (eb) lower or higher than 1 indicates a greater relative impact of the variable analyzed on men compared to women, or vice versa.

The base model (stage 1) shows statistically significant evidence that, as experience in the business and the position increases, managers tend to be male (p < 0.05). These results are consistent with our previous univariate analysis as well as the findings of Orser et al. (2010). In the first extended model (second stage), firm variables were added to gain explanatory power (in terms of several pseudo-R2 measures12). The results confirm that male export managers in comparison to their female counterparts work in firms with more experience in export activities (p < 0.05), a slightly longer experience in the industry (p < 0.1), and lead larger export teams (p < 0.05).

The second extended model (third stage), which considers interactions between personal and firm variables, just marginally added some explanatory power. Removing statistically non-significant variables from this model yields the final model included in Table 3. The results reveal that male export managers have not only higher experience in the company and larger teams but also a higher export ability (p < 0.05). Moreover, as the export focus of human resources increases, the proportion of women being export managers increases (p < 0.05). Although it could be argued that new companies with a strong internationalization strategy could be less influenced by a sociocultural history of gender segregation and might then have relied on female executives, in this context we obtain no evidence that firms experiential knowledge has a significant effect on the likelihood of export managers being men or women.

Fig. 1 helps to explicate the real meaning of interactions previously found as statistically significant. Regarding the export ability variable, at any given level of education, men are found to be more experienced than women, even if an inverse relationship is observed between these two variables. Regarding the export focus of human resources, the average experience of male managers is higher than female managers’ experience when export teams are small or mid-sized, but for larger teams, gender differences are reduced.13 It is possible that, to qualify for the leadership of bigger export teams, women are required to have more experience than men, which explains the odd value observed.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Interactive effects between variables: Export abilities of the manager and export focus of human resources.

|

5. Concluding remarks

Bearing in mind the potential for gender segregation in management positions, this article analyses the access and promotion of female managers in Spanish exporting firms. Together with traditional, debated vertical gender segregation (‘glass ceiling’), we investigate whether social expectations on gender roles impact the acceptance of women into boundary export management positions, a position that is more largely characterized by communal attributes than traditional, control-based management positions. Following a Social-Role Theory perspective, we postulate that social perceptions on the way men and women manage organizations together with interiorized gender-stereotypic expectations of managers may lead to horizontal segregation in contemporary firms.

Results confirmed the presence of vertical segregation in any managerial position because figures demonstrate that women still occupy fewer of these positions than men (in 1:4 proportion). Among personal variables, no significant differences are found in the level of formal education among women and men either as export managers or finance managers (control group). In contrast, male managers, especially export boundary managers, exhibit a longer experience than women both in the company and in the position, which could be explained by the still recent access of women to managerial roles. Moreover, a company profile shows that women work in younger, much less internationalized firms than men.

Regarding horizontal segregation, while descriptive results show a higher percentage of female managers in boundary management than in the finance position, such a numerical difference is not found to be statistically significant. However, if horizontal segregation could not be statistically confirmed, it was observed in terms of significant differences in the characteristics of managers for each position. In particular, women take, on average, one year less to reach boundary management positions than men, a difference in promotion that does not appear in the financial area. Such a faster promotion may indicate that communal skills that are socially ascribed to women are particularly welcomed in managing relationships with independent channels, promoting horizontal segregation.

In spite of results on the potential fit between the communal skills socially ascribed to women and inter-organizational export management roles, figures demonstrate that female export directors lead smaller teams than male ones do. Reasons for such a difference could be either because the women are working in small firms since they prefer to work with more flexible teams, or as a result of working in younger firms with a shorter export experience that would devote less resources to international activities. However, an alternative explanation could be that women are not given enough resources to develop export activity, which would suggest discrimination against women on the part of senior management. In this line, multivariate results suggest that women need to demonstrate a greater experience than men to obtain a large staff; again, this seems to reveal a lack of confidence by senior managers, who demand more guarantees from female managers than from male managers, although such an argument should be further analyzed.

Our research has several limitations. First, the study has used a direct question on biological sex as a proxy for gender in line with most of social surveys. Following Westbrook and Sapersteins (2015) suggestions, in the future, a questionnaire should be designed that distinguishes between sex and gender, incorporating aspects such as self-identified sex orientation and extending the binary gender categories to multiple gender-role orientations. Moreover, the effect of the androgynous gender-role orientation on boundary management should be particularly analyzed because recent research suggests it exhibits more desirable managerial traits than pure masculine or feminine stereotypes (Mueller and Dato-on, 2013 ; Pérez-Quintana and Hormiga, 2015). In addition, the design of our study is cross-sectional and survey-based, leading to data limitations that impede obtaining in-depth explanations of empirical results. Thus, it is not possible to know whether mens higher experience is the reason for their greater access to managerial positions (experience being deemed key to business performance by top management, see Hitt et al., 2001), or whether it is a consequence of womens managerial vertical segregation (the ‘glass ceiling’); qualitative case studies and longitudinal studies would add valuable evidence to answer this question and represent potential avenues of research for the future. Moreover, additional attributes of female managers such as ethnicity, culture, class, age, location and education could influence womens access to and experience of business management and should be deeply investigated (Marlow, 2014).

References

- Acker, 1990 J. Acker; Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations; Gender and Society, 4 (1990), pp. 139–158

- Acker, 1994 J. Acker; The gender regime of Swedish banks; Scandinavian Journal of Management, 10 (1994), pp. 117–130

- Adkins, 2001 L. Adkins; Cultural feminization: ‘Money, sex and power’ for women; Signs, 26 (2001), pp. 669–695

- Bales, 1950 R.F. Bales; Interaction process analysis: A method for the study of small groups; Addison-Wesley, Ready (1950)

- Barbera et al., 2000 E. Barbera, M. Sarrió, A. Ramos; Mujeres y estilos de dirección. El valor de la diversidad; Intervención Psicosocial, 9 (1) (2000), pp. 49–62

- Bass, 1998 B.M. Bass; Transformational leadership: Industry, military, and educational impact; Erlbaum, Mahwah (1998)

- Bello et al., 2003 D.C. Bello, C. Chelariu, L. Zhang; The antecedents and performance consequences of relationalism in export distribution channels; Journal of Business Research, 56 (2003), pp. 1–16

- Berenguer et al., 2004 G. Berenguer, E. Cerver, A. de la Torre, V. Torcal; El estilo directivo de las mujeres y su influencia sobre la gestión del equipo de trabajo en las cooperativas valencianas; CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 50 (2004), pp. 123–149

- Bingham and Quigley, 1995 F.G. Bingham Jr., C.J. Quigley Jr.; The effect of gender on sales managers’ and salespeoples perceptions of sales force control tools; Journal of Marketing Management, 5 (1995), pp. 62–70

- Blau et al., 2002 F.D. Blau, M.A. Ferber, A.E. Winkler; The economics of women, men and work; Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River (2002)

- Book, 2000 E.W. Book; Why the best man for the job is a woman; HarperCollins, New York (2000)

- Bruni et al., 2004 A. Bruni, G. Gherardi, B. Poggio; Entrepreneurship-mentality, gender and the study of women entrepreneurs; Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17 (2004), pp. 256–269

- Burke and Collins, 2001 S. Burke, K.M. Collins; Gender differences in leadership styles and management skills; Women in Management Review, 16 (2001), pp. 244–256

- Burns, 1978 J.M. Burns; Leadership; Harper & Row, New York (1978)

- Calas and Smircich, 1993 M.B. Calas, L. Smircich; Dangerous liaisons: The ‘feminine-in-management’ meets ‘globalization’; Business Horizons, 36 (1993), pp. 71–81

- Calas et al., 2007 M.B. Calas, L. Smircich, K.A. Bourne; Knowing Lisa? Feminist analyses of gender and entrepreneurship; D. Bilimoria, S.K. Piderit (Eds.), Handbook on women in business and management, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (2007), pp. 78–105

- Chang et al., 2003 T.-Z. Chang, P. Polsa, S.-J. Chen; Manufacturer channel management behavior and retailers performance: An empirical investigation of automotive channel; Supply Chain Management, 8 (2003), pp. 132–139

- Charlo and Núñez, 2012 M.J. Charlo, M. Núñez; La mujer directiva en la gran empresa española: Perfil, competencias y estilos de dirección; Estudios Gerenciales, 28 (124) (2012), pp. 87–105

- Chuang, 2010 Y.-S. Chuang; Balancing the stress of international business travel successfully: The impact of work-family conflict and personal stress; Journal of Global Business Management, 6 (2010), pp. 1–9

- Claes, 1999 M.T. Claes; Women, men and management styles; International Labor Review, 138 (4) (1999), pp. 431–446

- Cliff, 1998 J.E. Cliff; Does one size fit all? Exploring the relationship between attitudes towards growth, gender, and business size; Journal of Business Venturing, 13 (1998), pp. 523–542

- De Cabo et al., 2010 R.M. De Cabo, R. Gimeno, L. Escot; Discriminación en consejos de Administración: Análisis e implicaciones económicas; Revista de Economía Aplicada, 18 (2010), pp. 131–162

- Díaz and Jiménez, 2010 M.C. Díaz, J.J. Jiménez; Recursos y resultados de las pequeñas empresas: Nuevas perspectivas del efecto género; Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la Empresa, 42 (2010), pp. 151–176

- Dillman, 2000 D.A. Dillman; Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method; John Wiley & Sons, New York (2000)

- Doole et al., 2006 I. Doole, T. Grimes, S. Demack; An exploration of the management practices and processes most closely associated with high levels of export capability in SMEs; Marketing, Intelligence & Planning, 24 (2006), pp. 632–647

- Eagly, 1987 A.H. Eagly; Sex differences in social behavior: A social role interpretation; Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ (1987)

- Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt, 2001 A.H. Eagly, M.C. Johannesen-Schmidt; The leadership styles of women and men; Journal of Social Issues, 57 (2001), pp. 781–797

- Eagly et al., 2003 A.H. Eagly, M.C. Johannesen-Schmidt, M. Van Engen; Transformational, transactional, and laissez-fair leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men; Psychological Bulletin, 129 (2003), pp. 569–591

- Eagly and Johnson, 1990 A.H. Eagly, B.T. Johnson; Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis; Psychological Bulletin, 108 (2) (1990), pp. 233–256

- Eagly and Steffen, 1984 A.H. Eagly, V.J. Steffen; Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles; Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46 (4) (1984), pp. 735–754

- Eagly and Wood, 2012 A.H. Eagly, W. Wood; Social role theory; P.A.M. Van Lange, A.W. Kruglanski, E.T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology, Vol. 2, Sage, Thousand Oaks (2012), pp. 458–476

- Eagly et al., 2000 A.H. Eagly, W. Wood, A. Diekman; Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal; T. Eckes, H.M. Trautner (Eds.), The developmental social psychology of gender, Erlbaum, Mahwah (2000), pp. 123–174

- Eddleston et al., 2004 K.A. Eddleston, D.C. Baldridge, J.F. Veiga; Toward modelling the predictors of managerial career success: Does gender matter?; Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19 (4) (2004), pp. 360–385

- Fletcher, 1994 J.K. Fletcher; Castrating the female advantage: Feminist standpoint research and management science; Journal of Management Inquiry, 3 (1994), pp. 74–82

- Flórez et al., 2012 R. Flórez, J.M. Ramón, M.L. Vélez, J.M. Sánchez, P. Araújo, M.C. Álvarez-Dardet; The role of management control systems in interorganizational efficiency: An analysis of export performance; A. Davila, M.J. Epstein, J.-F. Manzoni (Eds.), Performance measurements & management control: Global issues, studies in managerial and financial accounting, Vol. 25, Emerald, Bingley (2012), pp. 195–222

- Friedman and Podolny, 1992 R.A. Friedman, J. Podolny; Differentiation of boundary spanning roles: Labor negotiations and implications for role conflict; Administrative Science Quarterly, 37 (1992), pp. 28–47

- García et al., 2012 M. García, D. García, A. Madrid; Caracterización del comportamiento de las Pymes según el género del gerente: Un estudio empírico; Cuadernos de Administración, 47 (2012), pp. 37–53

- Guillaume and Pochic, 2009 C. Guillaume, S. Pochic; What would you sacrifice? Access to top management and the work–life balance; Gender, Work and Organization, 16 (2009), pp. 14–36

- Gupta et al., 2009 V. Gupta, D.B. Turban, S.A. Wasti, A. Sikdar; The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur; Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 33 (2) (2009), pp. 397–417

- Harich and LaBahn, 1998 K.R. Harich, D.W. LaBahn; Enhancing international business relationships: A focus on customer perceptions of salesperson role performance including cultural sensitivity; Journal of Business Research, 42 (1998), pp. 87–101

- Heilman, 1983 M.E. Heilman; Sex bias in work settings: The lack of fit model; Research in Organizational Behavior, 5 (1983), pp. 269–298

- Heilman, 1995 M.E. Heilman; Sex stereotypes and their effects in the workplace: What we know and what we don’t know; Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 10 (6) (1995), pp. 3–26

- Helgesen, 1990 S. Helgesen; The female advantage; Doubleday, New York (1990)

- Hitt et al., 2001 M.A. Hitt, L. Bierman, K. Shimizu, R. Kochlar; Direct and moderating effects of human capital on strategy and performance in professional service firms: A resource-based perspective; Academy of Management Journal, 44 (2001), pp. 13–28

- Huerta and García, 2006 E. Huerta, C. García; La frontera de la innovación. ¿Dónde se encuentra la empresa española?; Claves de la economía mundial, Instituto Español de Comercio Exterior (2006), pp. 100–109

- Iglesias and Llorente, 2008 C. Iglesias, R. Llorente; Evolución reciente de la segregación laboral por género en España. Working Paper 13/2008; Instituto Universitario de Análisis Económico y Social (2008)

- ILO, 2004 ILO; Breaking through the glass ceiling: Women in management; International Labour Office, Geneva (2004)

- Instituto de la Mujer, 2007 Instituto de la Mujer; La discriminación laboral de la mujer: Una década a examen; Ministerio de Igualdad, Madrid (2007)

- Instituto de la Mujer, 2008 Instituto de la Mujer; Experiencias y perspectivas de competitividad en empresas con presencia de mujeres en los consejos de administración; Ministerio de Igualdad, Madrid (2008)

- ISOTES, 2012 ISOTES; La mujer directiva en España. Women as leaders; PriceWaterhouseCooper (2012)

- Jennings and McDougald, 2007 J.E. Jennings, M.S. McDougald; Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice; Academy of Management Review, 32 (2007), pp. 747–760

- Kaleka, 2002 A. Kaleka; Resources and capabilities driving competitive advantage in export markets: Guidelines for industrial exporters; Industrial Marketing Management, 31 (3) (2002), pp. 273–283

- Katsikea and Skarmeas, 2003 E. Katsikea, D.A. Skarmeas; Organisational and managerial drivers of effective export sales organisations: An empirical investigation; European Journal of Marketing, 37 (2003), pp. 1723–1745

- Katsikeas et al., 2000 C.S. Katsikeas, D.A. Skarmeas, E. Katsikea; Level of import development and transaction cost analysis; Industrial Marketing Management, 29 (2000), pp. 575–588

- Kelan, 2008 E.K. Kelan; The discursive construction of gender in contemporary management literature; Journal of Business Ethics, 81 (2008), pp. 427–445

- Kirchmeyer, 2002 C. Kirchmeyer; Gender differences in managerial careers: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow; Journal of Business Ethics, 37 (2002), pp. 5–24

- Koenig et al., 2011 A.M. Koenig, A.H. Eagly, A.A. Mitchell, T. Ristikari; Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms; Psychological Bulletin, 137 (2011), pp. 616–642

- Leonidou et al., 1998 L.C. Leonidou, C.S. Katsikeas, N.F. Piercy; Identifying managerial influences on exporting: Past research and future directions; Journal of International Marketing, 6 (1998), pp. 74–102

- Leonidou et al., 2006 L.C. Leonidou, D. Palihawadana, M. Theodosiou; An integrated model of the behavioural dimensions of the industrial buyer–seller relationships; European Journal of Marketing, 40 (1/2) (2006), pp. 145–173

- Lewis, 2014 P. Lewis; Postfeminism, femininities and organization studies: Exploring a new agenda; Organization Studies, 35 (12) (2014), pp. 1845–1866

- Liff et al., 1997 S. Liff, L. Worrall, C.L. Cooper; Attitudes to women in management: An analysis of West Midlands businesses; Personnel Review, 26 (1997), pp. 152–173

- Linstead et al., 2005 S. Linstead, J. Brewis, A. Linstead; Gender in change: Gendering change; Journal of Organizational Change Management, 18 (2005), pp. 542–560

- Love et al., 2016 J.H. Love, S. Roger, Y. Zhou; Experience, age, and exporting performance in UK SMEs; International Business Review, 25 (4) (2016), pp. 806–819

- Luo, 2006 Y. Luo; Toward the micro- and macro-level consequences of interactional justice in cross-cultural joint ventures; Human Relations, 59 (2006), pp. 1019–1047

- Lyness and Heilman, 2006 K.S. Lyness, M.E. Heilman; When fit is fundamental: Performance evaluations and promotions of upper-level female and male managers; Journal of Applied Psychology, 91 (2006), pp. 777–785

- Lyness and Schrader, 2006 K.S. Lyness, C.A. Schrader; Moving ahead or just moving? An examination of gender differences in senior corporate management appointments; Group & Organization Management, 31 (2006), pp. 651–676

- Marlow, 2014 S. Marlow; Exploring the future research agendas in the field of gender and entrepreneurship; International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 6 (2014), pp. 102–120

- Maxwell et al., 2007 G.A. Maxwell, S.M. Ogden, D. McTavish; Enabling the career development of female managers in finance and retail; Women in Management Review, 22 (2007), pp. 353–370

- Ministerio de Sanidad and Política Social e Igualdad, 2011 Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad; Trayectorias laborales de las mujeres que ocupan puestos de alta cualificación. Madrid; (2011)

- Morgan et al., 2004 N.A. Morgan, A. Kaleka, C.S. Katsikea; Antecedents of export venture performance: A theoretical model and empirical assessment; The Journal of Marketing, 68 (1) (2004), pp. 90–108

- Moskowitz et al., 1994 D.S. Moskowitz, E.J. Suh, J. Desaulniers; Situational influences on gender differences in agency and communion; Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66 (4) (1994), pp. 753–761

- Mueller and Dato-on, 2008 S.L. Mueller, M.C. Dato-on; Gender-role orientation as a determinant of entrepreneurial self-efficacy; Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 13 (1) (2008), pp. 3–20

- Mueller and Dato-on, 2013 S.L. Mueller, M.C. Dato-on; A cross cultural study of gender-role orientation and entrepreneurial self-efficacy; International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 9 (1) (2013), pp. 1–20

- OECD, 2011 OECD; Report on the Gender Initiative: Gender equality in education, employment and entrepreneurship; Meeting of the OECD Council at Ministerial Level, OECD, Paris, 25–26 May (2011)

- Orser et al., 2010 B. Orser, M. Spence, A. Riding, C.A. Carrington; Gender and export propensity; Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34 (2010), pp. 933–957

- Pérez-Quintana and Hormiga, 2015 A. Pérez-Quintana, E. Hormiga; The role of androgynous gender stereotypes in entrepreneurship. Working Papers Universitat de Barcelona; Collecció d’Empresa 2015/2 (2015)

- Piercy et al., 2003 N.F. Piercy, D.W. Cravens, N. Lane; The new gender agenda in sales management; Business Horizons, 46 (2003), pp. 39–46

- Piercy et al., 2001 N.F. Piercy, D.W. Cravens, N. Lane; Sales manager control strategy and its consequences: The impact of gender differences; Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 21 (1) (2001), pp. 25–35

- Pounder and Coleman, 2002 J.S. Pounder, M. Coleman; Women – better leaders than men? In general and educational management it still ‘all depends’; Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23 (3) (2002), pp. 122–133

- Powell, 1990 G.N. Powell; One more time: Do female and male managers differ; The Executive (August) (1990), pp. 68–75

- Rosener, 1990 J.B. Rosener; Ways women lead; Harvard Business Review, 68 (6) (1990), pp. 119–124

- Rosenkrantz et al., 1968 P. Rosenkrantz, S. Vogel, H. Bee, I. Broverman, D.M. Broverman; Sex-role stereotypes and self-concepts in college students; Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 32 (1968), pp. 287–295

- Sahin and Robinson, 2002 F. Sahin, E.P. Robinson; Flow coordination and information sharing in supply chains: Review, implications, and directions for future research; Decision Sciences, 33 (2002), pp. 505–536

- Schein, 2007 V.E. Schein; Women in management: Reflections and projections; Women in Management Review, 22 (2007), pp. 6–18

- Solomon, 1998 C.M. Solomon; Todays global mobility: Short-term assignments and other solutions; Global Workforce, 3 (4) (1998), pp. 12–17

- Stelter, 2002 N.Z. Stelter; Gender differences in leadership: Current social issues and future organizational implications; Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 8 (4) (2002), pp. 88–99

- Stogdill, 1963 R.M. Stogdill; Manual for the leader behavior description questionnaire-form XII; Bureau of Business Research, Ohio State University, Ohio (1963)

- Stroh et al., 1992 L.K. Stroh, J.M. Brett, A.H. Reilly; All the right stuff: A comparison of female and male managers career progression; Journal of Applied Psychology, 77 (3) (1992), pp. 251–260

- Tharenou et al., 1994 P. Tharenou, S. Latimer, D. Conroy; How do you make it to the top? An examination of influences on womens and mens managerial advancement; Academy of Management Journal, 37 (1994), pp. 899–931

- Theodosiou and Katsikea, 2007 M. Theodosiou, E. Katsikea; How management control and job-related characteristics influence the performance of export sales managers; Journal of Business Research, 60 (2007), pp. 1261–1271

- Thornton, 2012 G. Thornton; Women in senior management: Still not enough; Grant Thornton International Business Report (2012)

- Trinidad and Normore, 2005 C. Trinidad, A.H. Normore; Leadership and gender: A dangerous liaison?; Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26 (2005), pp. 574–590

- Vroom and Yetton, 1973 V.H. Vroom, P.W. Yetton; Leadership and decision-making; University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh (1973)

- Watson and Newby, 2005 J. Watson, R. Newby; Biological sex, stereotypical sex-roles, and SME owner characteristics; International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 11 (2) (2005), pp. 129–143

- Wayne et al., 1999 S.J. Wayne, R.C. Liden, M.L. Kraimer, I.K. Graf; The role of human capital, motivation and supervisor sponsorship in predicting career success; Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20 (1999), pp. 577–595

- Westbrook and Saperstein, 2015 L. Westbrook, A. Saperstein; New categories are not enough. Rethinking the measurement of sex and gender in Social Surveys; Gender & Society, 29 (4) (2015), pp. 534–560

- Williams and Chaston, 2004 J.E.M. Williams, I. Chaston; Links between the linguistic ability and international experience of export managers and their export marketing intelligence behavior; International Small Business Journal, 22 (2004), pp. 463–486

Notes

1. Gender stereotypes refer to social beliefs about the characteristics and attributes associated with each sex (Rosenkrantz, Vogel, Bee, Broverman, & Broverman, 1968).

2. Gender roles refer to the legitimate social function for each sex (Eagly & Steffen, 1984). As a result, the gender-role orientation refers to the degree of identification of a person with the attitudes, social behaviours and careers that are consistent with the social gender stereotypes; four gender roles are identified depending on scores of multiple gender traits: masculine, feminine, highly masculine and feminine (androgynous), and lowly masculine and feminine (undifferentiated).

3. Laissez-faire style managers would fail to take responsibility for managing, with no particular gender association.

4. Additionally, a maternal femininity and an excessive femininity are defined with the first restricting women’ activity to motherhood-based businesses and the second restricting womens behaviour to a dependent, vulnerable, and passive one seeking male approval, which prevents them from success (Lewis, 2014). We consider such femininities not being representative of female export managers in our cross-sectional study.

5. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. EPA-2005. Encuesta de Población Activa (metodología 2005). Available at: http://www.ine.es Retrieved 23.02.16.

6. Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. Encuesta de Población Activa. Available at: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia Retrieved 23.02.16.

7. For example, Leonidou et al. (2006) report a response rate of 13.51% when analyzing exporter-importer relationships.

8. Rapidness in promotion can be obtained as a difference between time in the firm and time in the position; we preferred to analyze both variables separately for a better comprehension of potential differences in promotion.

9. A p-value <0.1 was obtained in the median test, also suggesting a weakly significant difference in median values.

10. Additionally, a gender difference in the experience in finance activity experience was observed for the finance director sample (p-value < 0.05).

11. Love et al. (2016) state that each variable in this interaction term represents a different dimension of the firms experiential knowledge and could even run in opposite directions. Experience of the firm in export activities would inform on the accumulated knowledge of international markets, which would be expected to have a positive effect on the potential for international learning; time of the firm in the main industry, as a proxy for firm age, would inform on the internal organizational experience, including managerial routines with different levels of flexibility (or rigidity) that could enhance (or reduce, respectively) the potential for acquiring new knowledge, particularly that originating in international markets.

12. Due to the absence of a single statistics of goodness-of-fit for logistic regression, R2 of McFadden, R2 of Cox-Snell and R2 of Nagelkerke were considered to compare alternative models.

13. However, no women reported having management teams of the largest size, value 7 on a 7-point Likert scale).

Document information

Published on 12/06/17

Submitted on 12/06/17

Licence: Other

Share this document