Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The aim of the study was to understand the components associated with the types of perfectionism described as adaptive/healthy, maladaptive/unhealthy or non-perfectionism, which could offer positive or negative aspects to improve excellence and well-being, exploring the number and content of the latent perfectionism structure as a multidimensional construct in a sample of High Intellectual Abilities (HIA) students. Links with Positive and Negative perfectionism were also compared across perfectionism latent profiles. A total of n=137 HIA students, mean age 13.77 years (SD=1.99), participated in a survey. The Almost Perfect Scale Revised (APS-R) and Positive and Negative Perfectionism Scale-12 (PNPS-12) were used. Results obtained showed three latent classes (LC): ‘Unhealthy’ (LC1), ‘Healthy’ (LC2) and ‘No perfectionism’ (LC3). LC1 showed high scores on Discrepancy subscales but low in Order and High Standards. LC2 displayed higher scores on High Standards and Order. LC3 displayed low scores across all perfectionism facets. Statistically significant differences were found across latent profiles in almost all perfectionism features. Different patterns of associations with Positive and Negative perfectionism were obtained across latent profiles. These findings address the latent structure of perfectionisms in HIA students and allow us to delimit, analyze, and understand the tentative latent profiles within the HIA arena.

1. Introduction

High Intellectual Ability (HIA) is not a static attribute but the result of the expression of a neurobiological high potential for intellectual abilities, modulated by intra and interpersonal variables through the developmental trajectory, from infancy to adulthood (Olzewski-Kubilius, Subotnik, & Worrell, 2015). One of the intrapersonal variables that could influence the expression from the initial High potential to the adult eminence (or genius) is perfectionism.

Perfectionism is a multidimensional construct related to a cognitive control style with high standards of performance and different concerns about committing mistakes (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990; Hewitt & Flett, 1991). The concept of perfectionism has moved from a unidimensional to a multidimensional approach (Leone & Wade, 2017; Shafran, Cooper, & Fairburn, 2002). Thus, the vision of perfectionism is, nowadays, characterized as composed of multiple dimensions with a variety of measures that need to be considered when analyzing the different profiles that can be observed (Flett & al., 2014).

Perfectionism could be considered as a healthy construct with positive outcomes, including higher performance and academic achievement (Damian & al., 2017; Damian, Stoeber, Negru, & B?ban, 2014), but it could be associated with anxiety or depressive symptoms (Flett, Besser, & Hewitt, 2014; Roxborough & al., 2012). Hence, efforts are now devoted to gaining a deeper understanding of the many differences in the aspects that articulate each profile of perfectionism (Sastre-Riba, Pérez-Albéniz, & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2016).

Perfectionism is also considered to have a key role in the construction of personality traits and is considered a cognitive pattern. In addition, it has also been related to high intellectual ability as different potentialities that can lead to the achievement of excellence (Pyryt, 2007). Thus, perfectionism in HIA is interpreted as a cognitive style linked to the idea of excellence and performance in academic and different settings, (Damian, Stoeber, Negru-Subtirica, & B?ban, 2017; Pyryt, 2007), and well-being.

The study of perfectionism in HIA children and adolescents has received increasing attention due to the fact that some HIA students have shown high standards for achievement, sometimes extreme and impossible to reach, as well as negative reactions to academic failure (Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012). Nonetheless, the question about whether perfectionism is higher among children and adolescents with high intellectual abilities is, at this moment, in need of more empirical evidence (Baker, 1996; Parker, Portesová, & Stumpf, 2001) in order to provide better resources to parents, teachers and psychologists associated with the optimization of school performance and its role in the students’ digital culture.

Previous studies have supported the idea of a multidimensional manifestation of perfectionism in HIA students with healthy/adaptive and unhealthy/maladaptive consequences (Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012). For instance, the study by Parker (2002) revealed three different types of perfectionism in middle-school gifted students by means of the Frost and others’ scale (Frost & al., 1990) with students in the healthy/adaptive group scoring lower on neuroticism and higher on extroversion and agreeableness, and students in the unhealthy/maladaptive group scoring higher on neurosis, lower on agreeableness, but also higher on openness to experience, and finally, a third group of non-perfectionists. Other studies have found similar results. (Dixon, Lapsley, & Hanchon, 2004; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Parker & al., 2001; Rice & Richardson, 2014; Schuler, 2000; Sironic & Reeve, 2015; Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, & Ashby, 2001; Smith & Saklofske, 2017). For example, Dixon and others (2004), revealed analogous types of perfectionist students in a group of HIA adolescents, next to another group characterized by having negative perfectionism, that included high scores on organization, high standards, and concern for mistakes. This group was related with more psychological symptoms and dysfunctional coping.

Another study proposed three classes of perfectionism after controlling for neuroticism and conscientiousness, described as non-perfectionism, adaptive perfectionism and maladaptive perfectionism (Rice, Richardson, & Tueller, 2014). Recently, these three types of perfectionism were established in different samples of adolescents across the world, (Wang, Puri, Slaney, Methikalam, & Chadha, 2012; Wang, Yuen, & Slaney; Ortega, Wang, Slaney, & Morales, 2014). Other studies, however, propose a 6-class model after applying a latent class analysis of adolescents, where three of them were categorized as perfectionists and were labeled as adaptive perfectionism, non-perfectionism, externally motivated, maladaptive perfectionism, and mixed maladaptive perfectionism, whereas the other three represented non- perfectionism expressions (Sironic & Reeve, 2015).

It is worth noting that across most studies, healthy/adaptive perfectionism is linked with positive effects, excellence, and with higher levels of self-esteem, order and satisfaction in the relation with peers (Pyryt, 2007), On the contrary, unhealthy/maladaptive perfectionism is considered as negative, showing low levels of self-esteem, high levels of anxiety or discrepancy, whereas levels of well-being of non-perfectionism seem to be in between the two other groups (Wang, Permyakova, & Sheveleva, 2016).

In sum, depending on its composition, perfectionism could have a positive or negative impact, facilitating or inhibiting relevant skills, for instance, problem solving, metacognitive regulation, and excellence. Thus, perfectionism could promote or limit the optimal expression of the initial high intellectual potential and the well-being of these students and, therefore, the scientific, technological, artistic, or social progress in today’s digital world.

In order to establish appropriate interventions for the expression of talent, it is necessary to carry out an adequate evaluation of perfectionism in specific target groups, for instance HIA students. Thus, it may be interesting to analyze the typology of perfectionism using new methodological approaches to solve some limitations of previous cluster analyses in this area. With this regard, the latent class analysis (LCA) (dichotomous outcome) or the latent profile analysis (LPA) (continuous outcome) are relatively novel techniques that could enable a better understanding of the groups and profiles of perfectionism.

1.1. Objectives

The general objective was the understanding of the components associated with the types of perfectionism described as adaptive/healthy, maladaptive/unhealthy (Chan, 2007; Costa & al., 2016; Damian & al., 2017; Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012; Parker, 2002), or non-perfectionism, which could offer the positive aspects to improve excellence and well-being, as research in HIA literature supports.

The specific objectives were: a) to capture the latent structure of perfectionism dimensions in HIA children and adolescents; b) to establish associations with Positive and Negative Perfectionism through latent profiles of perfectionism, trying to distinguish the more healthy/adaptive ones to promote the optimal expression of high intellectual potential as a challenge for the digital era.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

A total of n=137 students with a previous professional diagnosis of HIA participated (60.8% male, 39.2% female) in the study. The ages ranged between 12 and 16 years old (M=13.77 years old; SD=1.99). All of them belonged to the enrichment program at the University of La Rioja.

2.2. Instruments

The measure of perfectionism was obtained applying:

a) The Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (APS-R) (Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, & Ashby, 2001). The APS-R consists of 23 items to measure adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism. It contains the subscales: 1) High Standards (7 items) which assesses the high standards the individual establishes; 2) Discrepancy subscale (12 items) aims to measure perception of inadequacy about personal standards and achievements; and 3) Order (4 items), related to the preference for neatness and orderliness. A seven-point Likert scale was used (1=‘Strongly disagree’, to 7=‘Strongly agree’). Previous studies have shown the adequate psychometric properties of the Spanish version with score reliability ranging from .67 (Standards) to .85 (Discrepancy) (Sastre-Riba & al., 2016).

b) The Positive and Negative Perfectionism Scale-12 (PNPS-12) (Chan, 2007; 2010). The PNPS consists of 12 items that intend to measure positive and negative perfectionism. There are two subscales: Positive (students’ realistic striving for excellence; 6 items), and Negative (students’ rigid adherence to perfection as well as a preoccupation for avoiding mistakes; 6 items). The PNPS has a five-point Likert scale (1=‘Strongly disagree’, and 5=‘Strongly agree’). The Spanish adaptation of the PNPS-12 was carried out according to the international regulation regarding test translation (Muñiz, Elosua, & Hambleton, 2013).

2.3. Procedure

A multidimensional intellectual measurement was administered to all HIA participants in the Enrichment program (Sastre-Riba, 2013), in order to amplify and standardize the intellectual profiles. Concretely: a) The Differential Aptitude Test (DAT) (Bennet, Seashore, & Wesman, 2000); and b) Torrance’s Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) (Torrance, 1974). The measurement instruments were administered to groups of no more than 10 students.

According to Castelló & Batlle (1998), participants scoring equal or over the 75th percentile in all the intellectual competencies were classified as gifted; participants with scores equal or above the 90th percentile in at least one or various convergent or divergent aptitudes (but not all) were considered as talented.

Informed written authorization was provided by parents or legal tutors. The confidentiality and the voluntary nature of the study was informed to all participants and parents. Participants did not receive any kind of incentive for their engagement. The researchers supervised the administration of the different tests and questionnaires. The study received the approval of the bioethics committee at the University of La Rioja and it was conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.4. Data analysis

Different steps were followed for data analysis:

1) Descriptive statistics for the measurements, and the correlation between APS-R and PNPS-12 by means of Pearson’s coefficient.

2) Latent profile analysis (LPA) using APS-R subscales, transformed into z scores, was performed to analyse whether there were discrete groups (classes) showing similar profiles. LPA models had to be compared in order to establish the optimal number of classes (i.e., class numbering). First, a 1-class model had to be evaluated. Then latent classes were added till the most suitable class solution was found. Several adjustment indexes, including likelihood ratios were considered to establish the best model. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (Akaike, 1987), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (Schwarz, 1978), and the sample-size adjusted BIC (ssaBIC) (Sciove, 1987) were analysed to have a better adjustment when lower values were reached. We attended to the Lo-Mendell-Rubin’s likelihood ratio test (LRT) (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001).

The likelihood ratios of the k-1 and k class models examine the null hypothesis of no statistically significant difference. Therefore, a p<0.05 suggests that the k class model provides a more accepted solution model than the k 1 class model. In addition, values of statistical significance (p>gt;gt;0.05) indicate that the solution (k-1) should be favoured with regards to its precision in reflecting the data. Then, it is possible to assess if the number of classes selected is appropriate by means of the bootstrapped parametric likelihood ratio test.

We also tested for the standardized measure of entropy. This value ranges from 0 to 1 and it measures the relative accuracy in participants’ classification. A higher value in this parameter reflects that the groups found are more separated (Ramaswamy, DeSarbo, Reibstein, & Robinson, 1993).

3) Calculation of the effect of latent class membership on the APS-R and PNPS-12 subscales by means of multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). Gender and age were used as covariates. Partial eta squared (2) indicated the effect size.

The statistical packages SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp Released, 2013) and Mplus 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2015) were used.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations

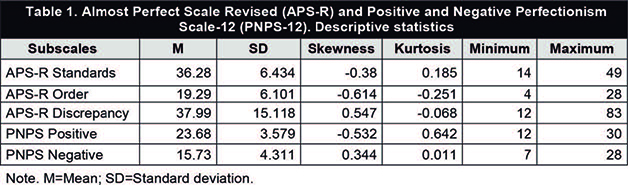

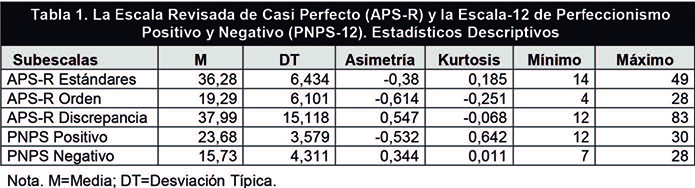

Descriptive statistics of the measures are depicted on Table 1.

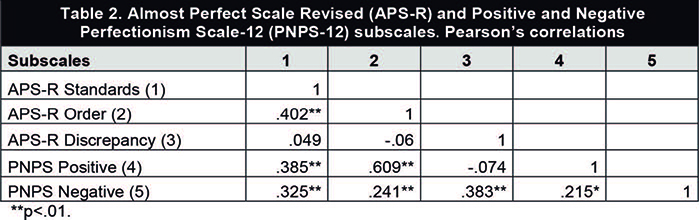

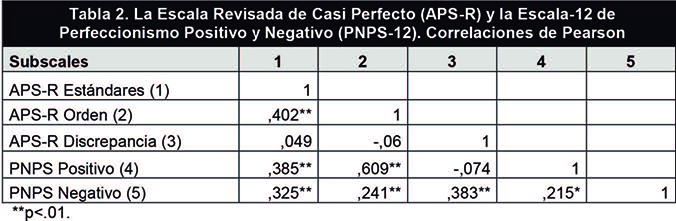

As reflected on Table 2, most correlations between APS-R subscales were statistically significant. The positive perfectionism subscale PNPS-12 was associated with Order. The Negative Perfectionism subscale (PNPS-12) was strongly associated with Discrepancy.

3.2. Identification of the latent profiles of perfectionism

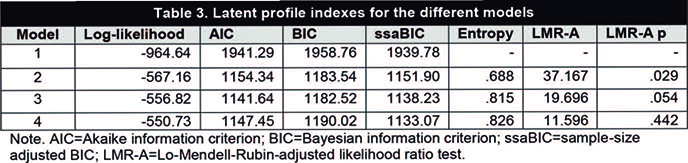

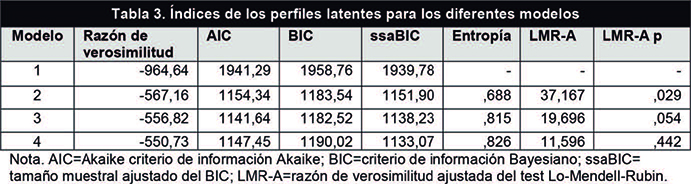

Four latent profile solutions were analyzed. The goodness-of-fit values for the different perfectionism models computed are shown in Table 3. The entropy value was <0.90 for the different solutions. The LMR-A p index for the 2-class model revealed that, compared to the 1-class model, there was an improvement that was statistically significant. Then, the comparison between the 2-class and 3-class solutions revealed lower values of AIC, BIC, ssaBIC and, in addition, a marginal significant LMR-A-LRT p-value (0.054) in the case of the 3-class model, indicating, thus, that this solution should be prioritized. The 4-class solution revealed non-significant LMR-A p value and similar AIC, BIC and ssaBIC values than the 3-class model. Thus, we chose the 3-class model as the most suitable one. For class 1, class 2, and class 3, the different average class membership was as follows: 0.928, 0.936, 0.85, and 0.90. These values revealed adequate discrimination.

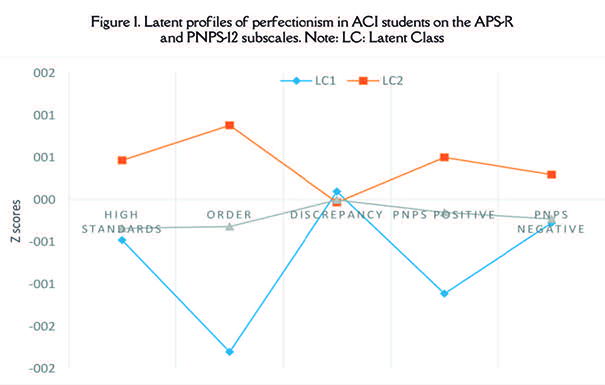

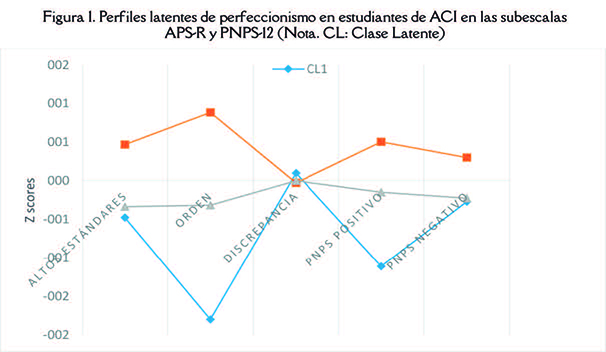

Following the 3-class model, a 14.59% (n=20) was included in class 1 (LC1), class 2 described (LC2) 44.52% (n=61), and class 3 (LC3) 40.87% (n=56) of the participants. Class 1, named ‘Unhealthy perfectionism’, revealed high scores on Discrepancy subscales and low in the rest. Participants in Class 2, identified as ‘Healthy perfectionism’, displayed higher scores on High Standards and Order. Participants in Class 3 denominated ‘Non perfectionism’, revealed low scores across all perfectionism components. Figure 1 depicts these three perfectionism profiles.

3.3. Validation of the perfectionism latent profiles

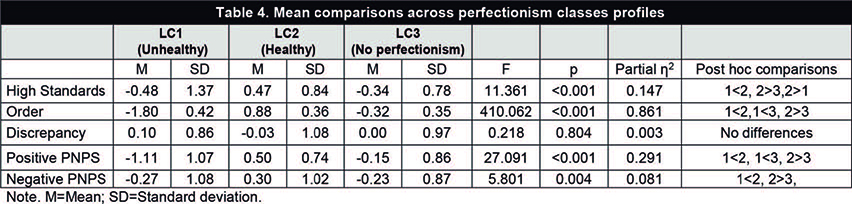

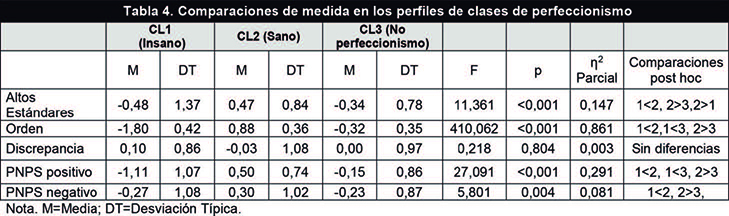

The MANCOVA values indicated a significant effect for group latent profiles [Wilk´s ?=0.131, F(10, 256)=45.029; p<0.001]. The mean and standard deviation and the p-values and effect sizes for 3-latent profile solution are shown in Table 4.

Attending to the Discrepancy scores, no significant statistical differences across the latent profiles were found. Different configurations of associations with Positive and Negative perfectionism of the PNPS-12 were found. In particular, ‘Healthy perfectionism’ scored higher, when compared to other latent classes, in High Standards, Order, and Positive Perfectionism.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Perfectionism is a multidimensional construct related to the accomplishment of excellence and well-being. Perfectionism is expressed as a continuum (Chan, 2007; Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012) of thoughts and behaviors with positive and negative aspects that are particularly relevant in high intellectual ability students, as they could modulate the striving for excellence expected in them (Pyryt, 2007).

Beyond the pathological and clinical point of view (Costa, Hausenblas, Oliva, Cuzzocrea, & Larcan, 2016; Donahue, Reilly, Anderson, Scharmer, & Anderson, 2018), this study takes a perspective of perfectionism as a cognitive trait regarded as irrelevant in the high intellectual capacity, trying to differentiate the healthy/adaptive perfectionism from the unhealthy/maladaptive perfectionism. Considering the relationship between perfectionism, academic and personal achievement goals, and the fact that perfectionism is related to the inhibition or enhancement of different behaviors related to the consecution of these goals, detecting the different types of perfectionism and its components is indicated. This can lead to a better understanding of the student and enable the optimization of their motivation, efforts and executive regulation, preserving their well-being and providing a higher performance in academic settings. This is even more relevant in HIA individuals, where the existence of a high potential does not ensure the consecution of their goals.

Results obtained in the present study, by means of latent cluster analyses, performed applying the APS-R scale, found a three-cluster solution of perfectionism, similar to Frost’s model (Frost & al., 1990) or the APS-R. This three-cluster solution is different to the 2 dimensional model (Healthy - Non Healthy) found by Stoeber (2018). Conversely, the results found are similar to Slaney’s and others (2001) revealing a three-cluster structure: Cluster 1 (Unhealthy/Maladaptive perfectionism); Cluster 2 (Healthy/Adaptive perfectionism); and Cluster 3 (Non-Perfectionism). Contrary to Mofield and Parker-Peters (2015), the three clusters are validated, including Cluster 2.

Nevertheless, some differences regarding the scores of clusters’ components arise. Cluster 1 (Unhealthy/Maladaptive perfectionism) was defined by high scores on Standards and Discrepancy, and low scores in Order (Parker, 2002; Speirs-Neumeister, 2007), but contrary to other studies (Chan, 2012; Mofield & others, 2015), which show high scores in all components. Cluster 2 (Healthy/Adaptive perfectionism) revealed high scores in Standards and Order but not on Discrepancy, corroborating the results of Chan (2012) and Parker (1997), suggesting that these students could be more adaptive than those of Cluster 1. Cluster 3 (Non perfectionism), similar to previous studies, (Chan, 2007; Chan, 2010) scored lower than the other two groups on all components except on Discrepancy where no statistically significant differences were found. Thus, and considering the absence of significant differences in Discrepancy, this component cannot be considered, attending to the results found in this study, as a differential element of Healthy/adaptive perfectionism or Unhealthy/non adaptive perfectionism, contrary to Chan (2012). Correlation analyses between the PNPS-R and the APS-R showed a significant and positive correlation between Order and High Standards with Positive Perfectionism; on the other hand, a high correlation was obtained between Discrepancy and Negative perfectionism, but not with Positive Perfectionism. In addition, Discrepancy showed a significant correlation with Unhealthy/maladaptive perfectionism, and with Healthy/adaptive perfectionism.

The results found in the present study could provide relevant insight regarding the need to differentiate the positive from the negative perfectionism, as well as the Healthy/adaptive versus Unhealthy/maladaptive perfectionism in students with HIA (Chan, 2012). The early identification and guidance of HIA students with perfectionism could be essential in order to optimize the striving for excellence and achievement goals as a manifestation of their whole potential. In all, it is necessary to promote Healthy/ Adaptive perfectionism and adult eminence with exceptional products offered by what society calls genius. (Chan, 2012).

The results also enable a deeper understanding of the manifestation of perfectionism in HIA as one of its modulating variables to the expression of genius in adulthood. This could have a relevant impact in parents, educators, and psychologists at schools as the manifestation of perfectionism in HIA is heterogeneous. Some students reveal no perfectionism, others display healthy perfectionism, and, finally, others show an unhealthy manifestation of this psychological construct. Therefore, parents and professionals at school should promote activities and interventions in which the components of healthy perfectionism (high standards and order) can be enhanced. The digital era is generating a new scenario. Children and adolescents are surrounded by stimuli, devices, and activities that generate a new perspective in the development of cognitive skills and the way in which executive functions regulate their cognitive skills. Therefore, research must be done in order to better understand this phenomenon and this new context.

Finally, and considering the key role of motivation for the manifestation of high intellectual potential, more research about the relationship between motivation and perfectionism is needed, in order to promote an optimal expression of the intellectual potential and well-being of HIA students (Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012). The consideration of all these aspects will enable better school intervention of HIA students that could lead to the implementation of educational interventions that take into consideration these and other relevant aspects such as digital culture.

Funding Agency

This research is financed by the Spanish Ministry of Education with the National project of Excellence EDU2016-78440P, and by the Convention with the Ministry of Education, Training and Employment of the Autonomous Government of La Rioja (Spain).

References

Akaike, H. (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52, 317-332. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294359

Baker, J.A. (1996). Everyday stressors of academically gifted adolescents. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 7(2), 356-368. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X9600700203

Bennet, G.K., Seashore, H.G., & Wesman, A.G. (2000). DAT-5. Test de Aptitudes Diferenciales. Madrid: TEA.

Castelló, A., & Batlle, C. (1998). Aspectos teóricos e instrumentales en la identificación del alumnado superdotado y talentoso. Propuesta de un protocolo. Faisca Revista Altas Capacidades, 6, 26-66.

Chan, D.W. (2007). Positive and negative perfectionism among Chinese gifted students in Hong Kong: Their relationships to general self-efficacy and subjective well-being. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 31, 77-102. https://doi.org/10.4219/jeg-2007-512

Chan, D.W. (2010). Perfectonism among Chinese gifted and nongifted students in Hong-Kong: The use of the revised almost perfect scale. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34, 68-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235321003400104

Chan, D.W. (2012). Life satisfaction, happiness, and the growth mindset of healthy and unhealthy perfectionists among hong kong chinese gifted students. Roeper Review, 34(4), 224-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2012.715333

Costa, S., Hausenblas, H.A., Oliva, P., Cuzzocrea, F., & Larcan, R. (2016). Maladaptive perfectionism as mediator among psychological control, eating disorders, and exercise dependence symptoms in habitual exerciser. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 77-89. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.004

Damian, L.E., Stoeber, J., Negru, O., & B?ban, A. (2014). Perfectionism and achievement goal orientations in adolescent school students. Psychology in the Schools, 51(9), 960-971. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21794

Damian, L.E., Stoeber, J., Negru-Subtirica, O., & B?ban, A. (2017). On the development of perfectionism: The longitudinal role of academic achievement and academic efficacy. Journal of Personality, 85(4), 565-577. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12261

Dixon, F.A., Lapsley, D.K., & Hanchon, T.A. (2004). An empirical typology of perfectionism in gifted adolescents. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(2), 95-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620404800203

Donahue, J.M., Reilly, E.E., Anderson, L.M., Scharmer, C., & Anderson, D.A. (2018). Evaluating Associations between perfectionism, emotion regulation, and eating disorder symptoms in a mixed-gender sample. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(11), 900-904. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000895

Fletcher, K.L., & Speirs-Neumeister, K.L. (2012). Research on perfectionism and achievement motivation: implications for gifted students. Psychology in the Schools, 49(7), 668-677. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21623

Flett, G.L., Besser, A., & Hewitt, P.L. (2014). Perfectionism and interpersonal orientations in depression: An analysis of validation seeking and rejection sensitivity in a community sample of young adults. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 77(1), 67-85. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2014.77.1.67

Frost, R.O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449-468. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172967

Hewitt, P.L., & Flett, G.L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456-70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

IBM Corp Released (Ed.) (2013). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Leone, E.M., & Wade, T.D. (2017). Measuring perfectionism in children: A systematic review of the mental health literature. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(5), 553-567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1078-8

Lo, Y., Mendell, N.R., & Rubin, D.B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767-778. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/88.3.767

Mofield, E.L., & Parker Peters, M. (2015). The relationship between perfectionism and overexcitabilities in gifted adolescents. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 38(4), 405-427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353215607324

Muñiz, J., Elosua, P., & Hambleton, R.K. (2013). Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests. Psicothema, 25, 151-157. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.24

Muthén, L.K., & Muthén, B.O. (n.d.). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. http://bit.ly/2YI5PWA

Olzewski-Kubilius, P., Subotnik, R.F., & Worrell, F.C. (2015). Repensando las altas capacidades: una aproximación evolutiva. Revista de Educación, 368, 40-65. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2015-368-297

Ortega, N.E., Wang, K.T., Slaney, R.B., Hayes, J.A., & Morales, A. (2014). Personal and familial aspects of perfectionism in latino/a students. The Counseling Psychologist, 42(3), 406-427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012473166

Parker, W.D. (1997). An empirical typology of perfectionism in academically talented children. American Educational Research Journal, 34(3), 545. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163249

Parker, W.D. (2002). Perfectionism and adjustment in gifted children. In Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 133-148). Washington: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-005

Parker, W.D., Portesová, S., & Stumpf, H. (2001). Perfectionism in mathematically gifted and typical czech students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 25(2), 138-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320102500203

Pyryt, M.C. (2007). The Giftedness/perfectionism connection: Recent research and implications. Gifted Education International, 23(3), 273-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940702300308

Ramaswamy, V., DeSarbo, W.S., Reibstein, D.J., & Robinson, W.T. (1993). An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science, 12, 103-124. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.12.1.103.

Rice, K.G., & Richardson, C.M.E. (2014). Classification challenges in perfectionism. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(4), 641-648. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000040

Rice, K.G., Richardson, C.M.E., & Tueller, S. (2014). The Short form of the revised almost perfect scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96(3), 368-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.838172

Roxborough, H.M., Hewitt, P.L., Kaldas, J., Flett, G.L., Caelian, C.M., Sherry, S., & Sherry, D.L. (2012). Perfectionistic Self-presentation, socially prescribed perfectionism, and suicide in youth: A test of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(2), 217-233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00084.x

Sastre-Riba, S. (2013). High intellectual ability: Extracurricular enrichment and cognitive management. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 36(1), 119-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353212472407

Sastre-Riba, S., Pérez-Albéniz, A., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2016). Assessing perfectionism in children and adolescents: Psychometric properties of the almost perfect scale revised. Learning and Individual Differences, 49, 386-392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.022

Schuler, P.A. (2000). Perfectionism and gifted adolescents. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 11(4), 183-196. https://doi.org/10.4219/jsge-2000-629

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics, 6, 461-464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136

Sciove, S.L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52, 333-343. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294360

Shafran, R., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C.G. (2002). Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 773-791. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00059-6

Sironic, A., & Reeve, R.A. (2015). A combined analysis of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS), Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS), and Almost Perfect Scale - Revised (APS-R): Different perfectionist profiles in adolescent high school students. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1471-1483. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000137

Slaney, R., Rice, K., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J.S. (2001). The Revised almost perfect scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 34(3), 130-145. https://doi.org/10.1037/t02161-000

Smith, M.M., & Saklofske, D.H. (2017). The structure of multidimensional perfectionism: Support for a bifactor model with a dominant general factor. Journal of Personality Assessment, 99(3), 297-303. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2016.1208209

Speirs-Neumeister, K. (2007). Perfectionism in gifted students: An overview of current research. Gifted Education International, 23(3), 254-263. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940702300306

Stoeber, J. (2018). Comparing Two short forms of the hewitt-flett multidimensional perfectionism scale. Assessment, 25(5), 578-588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116659740

Torrance, E. (1974). The Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking - Norms -Technical manual research Edition. Princeton, NJ: Personnel. https://doi.org/10.1037/t05532-000

Wang, K.T., Permyakova, T M., & Sheveleva, M.S. (2016). Assessing perfectionism in Russia: Classifying perfectionists with the short almost perfect scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 92, 174-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2015.12.044

Wang, K.T., Puri, R., Slaney, R.B., Methikalam, B., & Chadha, N. (2012). Cultural validity of perfectionism among Indian students. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 45(1), 32-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175611423109

Wang, K.T., Yuen, M., & Slaney, R.B. (2009). Perfectionism, depression, loneliness, and life satisfaction. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(2), 249-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000008315975

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El objetivo de este estudio fue comprender los componentes asociados a distintos tipos de perfeccionismo descrito como: adaptativo/sano, mal adaptativo/insano o no perfeccionismo que pueden tener efectos positivos o negativos para el logro de la excelencia. Se exploró el número y contenido de las estructuras latentes del perfeccionismo como constructo multidimensional en una muestra de n=137 estudiantes con Altas Capacidades Intelectuales (ACI) con una media de edad de 13,77 años (DT=1,99). La conexión con el perfeccionismo positivo y negativo se analizó sobre la base de los diferentes perfiles de perfeccionismo. Se utilizaron las escalas «Almost Perfect Scale Revised» (APS-R) y la «Positive and Negative Perfectionism Scale-12». Los resultados mostraron tres clases latentes de perfeccionismo: «No Sano» (CL1), «Sano» (CL2) y «No Perfeccionista» (CL3). La CL1 mostró puntuaciones más altas en las subescalas de Discrepancia y bajas en Orden y Altos Estándares. La CL2 reveló puntuaciones altas en Altos Estándares y Orden. La CL3 mostró bajas puntuaciones en todos los dominios de perfeccionismo. Las diferencias fueron estadísticamente significativas entre las clases latentes en los dominios del perfeccionismo. Asimismo, se encontraron diferentes patrones de asociaciones de las clases latentes con el perfeccionismo Positivo y Negativo. Los resultados encontrados permiten atender a las estructuras latentes de perfeccionismo en estudiantes con ACI, que posibilitan delimitar, analizar y entender posibles perfiles latentes.

1. Introducción

La Alta Capacidad Intelectual (ACI) no es un atributo estable, sino el resultado de la expresión de un alto potencial neurobiológico para la competencia intelectual, modulado por variables intra e interpersonales a lo largo de la trayectoria del desarrollo, desde la pequeña infancia hasta la adultez (Olzewski-Kubilius, Subotnik, & Worrell, 2015). Una de las variables intrapersonales que puede influir en la expresión del alto potencial inicial hasta la eminencia adulta (o genio) es el perfeccionismo.

El perfeccionismo es un constructo multidimensional relacionado con un estilo de control cognitivo configurado por estándares de rendimiento y preocupación en mayor o menor medida por cometer errores (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990; Hewitt & Flett, 1991). El concepto de perfeccionismo ha cambiado desde una visión inicialmente unidimensional hacia la multidimensional (Leone & Wade, 2017; Shafran, Cooper, & Fairburn, 2002). En consecuencia, actualmente se caracteriza por estar compuesto por múltiples dimensiones que dan lugar a distintos instrumentos de medida, cuestión a tener en cuenta al analizar los perfiles posibles que se observen (Flett & al., 2014).

El perfeccionismo puede ser un constructo saludable con resultados positivos que pueden incluir altos logros y rendimiento académico (Damian & al., 2017; Damian, Stoeber, Negru, & B?ban, 2014), pero a veces puede estar asociado con síntomas de ansiedad y depresión (Flett, Besser, & Hewitt, 2014; Roxborough & al., 2012). Por ello, el esfuerzo actual se dirige a comprender con mayor precisión las diferencias entre los aspectos que articulan el perfil de perfeccionismo (Sastre-Riba, Pérez-Albéniz, & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2016). También se considera que el perfeccionismo puede tener un rol central en la construcción de rasgos de personalidad, considerándose un patrón cognitivo. También, ha sido vinculado con la Alta Capacidad Intelectual (ACI), dada su relación con la consecución de logros de excelencia (Pyryt, 2007). Por ello, se interpreta como un estilo cognitivo ligado a la idea de excelencia, rendimiento académico y bienestar (Damian, Stoeber, Negru-Subtirica, & B?ban, 2017; Pyryt, 2007) y bienestar.

El estudio del perfeccionismo en niños y adolescentes se ha incrementado recientemente, dado que algunos estudiantes con ACI muestran altos estándares de rendimiento, a veces excesivos e imposibles de alcanzar, así como reacciones negativas frente al fracaso académico (Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012). No obstante, la cuestión sobre si existe mayor prevalencia del perfeccionismo en estudiantes con ACI todavía no está resuelta, siendo preciso obtener más evidencias (Baker, 1996; Parker, Portesová, & Stumpf, 2001) con el fin de poder ofrecer guía y soporte a los padres, profesores y profesionales vinculados a la optimización del rendimiento escolar y el papel de este en la cultura digital de los estudiantes.

Algunos estudios previos han mostrado que el perfeccionismo tiene una manifestación multidimensional en la ACI con consecuencias saludables/adaptativas pero también no saludables/mal adaptativas (Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012). Por ejemplo, Parker (2002), administrando la escala de Frost y otros (1990), mostró tres tipos de perfeccionismo: un grupo saludable/adaptativo, con bajas puntuaciones en neuroticismo y mayor extroversión y agradabilidad, otro grupo no saludable/mal adaptativo con alta puntuación en neuroticismo, baja en agradabilidad y alta en apertura a la experiencia y, finalmente, otro grupo de no perfeccionistas. Otros estudios han obtenido resultados similares (Dixon, Lapsley, & Hanchon, 2004; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Parker & al., 2001; Rice & Richardson, 2014; Schuler, 2000; Sironic & Reeve, 2015; Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, & Ashby, 2001; Smith & Saklofske, 2017). Por ejemplo, Dixon y otros (2004) revelaron los mismos tipos de estudiantes perfeccionistas en un grupo de adolescentes con ACI, junto a otro grupo caracterizado por mostrar un perfeccionismo negativo incluyendo altas puntuaciones en organización, altos estándares y preocupación por los errores. Este grupo fue el de mayor número de síntomas psicológicos y adaptación disfuncional. Otra investigación propuso tres tipos de perfeccionismo tras controlar su neuroticismo y gusto por el detalle, denominados como: no perfeccionismo, perfeccionismo adaptativo y perfeccionismo mal adaptativo (Rice, Richardson, & Tueller, 2014). Recientemente, estos tres tipos de perfeccionismo se han corroborado en otros estudios en diferentes países (Wang, Puri, Slaney, Methikalam, & Chadha, 2012; Wang, Yuen, & Slaney, 2009; Ortega, Wang, Slaney, & Morales, 2014). No obstante, otras investigaciones proponen un modelo de 6 clases tras aplicar un análisis de clases latentes a adolescentes. Tres de ellos fueron categorizados como perfeccionistas y distribuidos como perfeccionismo adaptativo, no-perfeccionismo, motivado externamente, perfeccionismo mal adaptativo y perfeccionismo mal adaptativo mixto, mientras que las otras tres clases representaban expresiones del no perfeccionismo (Sironic & Reeve, 2015).

Es interesante señalar que en casi todos los estudios el perfeccionismo saludable/adaptativo se relaciona con efectos positivos, excelencia y altos niveles de autoestima, orden y satisfacción con la relación entre iguales (Pyryt, 2007). En cambio, el perfeccionismo no saludable/mal adaptativo se considera negativo dado que muestra bajos niveles de autoestima, altos niveles de ansiedad o discrepancia; mientras que los niveles de bienestar que acompañan al no perfeccionismo se sitúan entre los de los otros dos grupos descritos (Wang, Permyakova, & Sheveleva, 2016).

En suma, en función de su composición, el perfeccionismo puede tener un impacto positivo o negativo, facilitando o inhibiendo habilidades relevantes para, por ejemplo, la resolución de problemas, regulación metacognitiva y la excelencia. Por lo tanto, puede promover o limitar la óptima expresión del alto potencial intelectual inicial, así como el bienestar de estos estudiantes y, consecuentemente, el progreso científico, tecnológico artístico o social en el mundo actual y digital.

Con el fin de establecer las intervenciones apropiadas para la expresión del talento, es necesario llevar a cabo una evaluación fiable del perfeccionismo en grupos diferenciados, por ejemplo, con altas capacidades intelectuales. Por ello, es importante analizar la tipología del perfeccionismo mediante el uso de nuevas metodologías que permitan resolver algunas limitaciones de los análisis de clúster existentes; de ahí que el análisis de clases latentes (ACL) (dicotómico) o el análisis del perfil latente (APL) (continuo) son técnicas novedosas que podrían facilitar una mejor comprensión de los grupos y perfiles de perfeccionismo.

1.1. Objetivos

El objetivo general consistió en comprender los componentes asociados con los tipos de perfeccionismo descritos como adaptativo/saludable, mal adaptativo/no saludable (Chan, 2007; Costa & al., 2016; Damian & al., 2017; Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012; Parker, 2002), o no-perfeccionismo, que podrían identificar los aspectos positivos para optimizar el logro de la excelencia y el bienestar, de acuerdo con las evidencias de la literatura científica sobre ACI.

Los objetivos específicos son: a) capturar la estructura latente de las dimensiones de perfeccionismo en niños y adolescentes con ACI; b) establecer asociaciones con el Perfeccionismo Positivo y Negativo mediante los perfiles latentes de perfeccionismo, intentando distinguir los más saludables/adaptativos para promover la óptima expresión del alto potencial intelectual como uno de los cambios en la era digital.

2. Materiales y métodos

2.1. Participantes

Un total de n=137 estudiantes con diagnóstico de ACI participaron en el estudio (60,8% hombres, 39,2% mujeres). Las edades oscilaron entre los 12 y 16 años (M=13,77; DT=1,99). Todos los estudiantes asistían al programa de enriquecimiento de la Universidad de La Rioja y tenían un diagnóstico profesional previo de ACI.

2.2. Instrumentos

Las medidas de perfeccionismo se obtuvieron mediante la aplicación de:

a) La «Almost Perfect Scale-Revised» (APS-R) (Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, & Ashby, 2001). La APS-R está formada por 23 ítems que miden el perfeccionismo adaptativo y mal adaptativo. La APS-R contiene las siguientes subescalas: 1) Alto estándar (7 ítems) que mide los altos estándares que establece la persona; 2) Discrepancia (12 ítems) destinada a medir la percepción de inadecuación sobre los estándares individuales y el logro; y 3) Orden (4 ítems), relacionada con la preferencia hacia la pulcritud y la organización. La escala tiene un formato de respuesta Likert con 7 opciones de respuesta (1=«Totalmente en desacuerdo», 7=«Totalmente de acuerdo»). Estudios previos han mostrado unas adecuadas propiedades psicométricas de las subescalas en la versión española con índices de fiabilidad de las puntuaciones oscilando entre 0,67 (Estándares) y 0,85 (Discrepancia) (Sastre-Riba & al., 2016).

b) La «Positive and Negative Perfectionism Scale-12» (PNPS-12) (Chan, 2007; 2010). La PNPS-12 está formada por 12 ítems que pretenden medir perfeccionismo positivo y negativo. Existen dos subescalas: Positivo (esfuerzo realista de los estudiantes para lograr la excelencia; 6 ítems) y Negativo (adherencia rígida de los estudiantes a la perfección, además de preocupación por evitar errores; 6 ítems). La PNPS-12 tiene un formato de respuesta tipo Likert con cinco opciones de respuesta (1=«Totalmente en desacuerdo» y 5=«Totalmente de acuerdo»). La adaptación al castellano de la PNPS-12 se llevó a cabo atendiendo a la normativa internacional para la traducción de test (Muñiz, Elosua, & Hambleton, 2013).

2.3. Procedimiento

Una medida multidimensional de funcionamiento intelectual fue administrada a todos los participantes con ACI del programa de Enriquecimiento (Sastre-Riba, 2013) con el fin de estandarizar los perfiles intelectuales. En concreto: a) El test de Aptitudes Diferenciales «Differential Aptitude Test» DAT (Bennet, Seashore, & Wesman, 2000); y b) El test de Torrance de pensamiento creativo («Torrance Creative Thinking Test», TCTT) (Torrance, 1974). Los instrumentos de medida fueron administrados en grupos de no más de 10 estudiantes. Siguiendo a Castelló y Batlle (1998), los participantes con puntuaciones iguales o superiores al percentil 75 en todas las competencias intelectuales fueron clasificados como superdotados; los participantes con puntuaciones iguales o superiores al percentil 90 en al menos una o varias aptitudes convergentes o divergentes (no en todas) fueron considerados como talentosos.

Los padres o tutores legales proporcionaron consentimiento escrito. Se informó a los padres y a todos los participantes acerca de la confidencialidad de las respuestas y la naturaleza voluntaria del estudio. Los participantes no recibieron ningún tipo de incentivo por su participación. Los investigadores supervisaron la administración de los diferentes test y cuestionarios. El estudio recibió la aprobación del comité de bioética de la Universidad de La Rioja y se llevó a cabo siguiendo los principios de la Declaración de Helsinki.

2.4. Análisis de datos

Los pasos para el análisis de datos fueron los que siguen:

1) Cálculo de los estadísticos descriptivos de las medidas y la correlación entre la APS-R y la PNPS-12 mediante el coeficiente de Pearson.

2) Análisis de clases latentes (ACL) usando las subescalas de la APS-R, trasformadas en puntuaciones z, para analizar si había grupos discrecionales (clases), que mostraran perfiles semejantes. Los modelos del ACL se comparan con el fin de establecer el número óptimo de clases (por ejemplo, la numeración de clases). Primeramente, el modelo de una clase es evaluado. A continuación, se añaden clases latentes hasta que se alcanza la solución más indicada. Diferentes índices de ajuste, incluyendo la razón de verosimilitud, son considerados para establecer el mejor modelo. El Criterio de Información Akaike («Akaike Information Criterion», AIC) (Akaike, 1987), el criterio de Información Bayesiano («Bayesian Information Criterion», BIC) (Schwarz, 1978) y el criterio de ajuste del tamaño muestral del BIC («sample size adjusted BIC», ssaBIC) (Sciove, 1987) son analizados y muestran un mayor ajuste cuando se alcanzan valores inferiores. Se atendió al test de la razón de verosimilitud de Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LRT) (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001).

Las ratios de verosimilitud de los modelos de clase de k-1 y k examinan la hipótesis nula de que no existen diferencias estadísticamente significativas. Por lo tanto, una p<lt;lt;0.05 sugiere que el modelo de k clases tiene una solución más aceptada que el modelo de clases k-1. Además, los valores de significación estadística (p>gt;gt;0.05) indican que la solución (k-1) debería de escogerse como más indicada a la hora de reflejar de manera más precisa los datos. Por lo tanto, es posible medir si el número de clases seleccionadas es adecuado mediante el test de remuestreo paramétrico de la razón de verosimilitud. También se analizó la medida estandarizada de entropía. Este valor oscila entre 0 y 1 y mide la precisión relativa alcanzada en la clasificación de los participantes. Un valor más alto en este parámetro refleja que los grupos encontrados se encuentran más separados (Ramaswamy, DeSarbo, Reibstein, & Robinson, 1993).

3) Cálculo del efecto de los miembros de clases latentes en las subescalas de la APS-R y la PNPS-12 por medio del análisis multivariado de la covarianza (MANCOVA). Se utilizaron el género y la edad como covariables. Como indicador del tamaño del efecto se utilizó el eta cuadrado parcial (2). Se utilizaron los paquetes estadísticos SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp Released, 2013) y Mplus 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2015).

3. Resultados

3.1. Descriptivos estadísticos y correlaciones de Pearson

Los estadísticos descriptivos de las medidas se muestran en la Tabla 1. Como puede observarse en la Tabla 2, la mayoría de las correlaciones entre las sub-escalas de la APS-R fueron estadísticamente significativas. La subescala de perfeccionismo Positivo de la PNPS-12 se asoció con Orden. La subescala de perfeccionismo Negativo (PNPS-12) mostró una fuerte correlación con Discrepancia.

3.2. Identificación de los perfiles latentes de perfeccionismo

Se analizaron cuatro soluciones de clases latentes. Los valores de bondad de ajuste para los diferentes modelos computados se muestran en la Tabla 3. El valor de entropía de las diferentes soluciones fue <lt;lt;0.90. El índice p de LMR-A para el modelo de dos clases reveló que había una mejora que fue estadísticamente significativa en comparación con el modelo de una clase. A continuación, la comparación entre el modelo de dos clases y el modelo de tres clases reveló unos valores de AIC, BIC, ssaBIC y, además, un valor p marginal significativo de LMR-A-LT (0,054) en el caso del modelo de tres clases, indicando, por lo tanto, que se debía priorizar el modelo de tres clases. El modelo de cuatro clases mostró valores de p no significativos en el LMR-A y valores de AIC, BIC y ssaBIC similares al modelo de tres clases. Por ello, se escogió el modelo de tres clases como el más indicado. Para las clases 1, 2 y 3, las diferentes medias de pertenencia a la clase fueron las siguientes: 0,928, 0,936, 0,85 y 0,90. Estos valores indican una adecuada discriminación.

Atendiendo al modelo de 3 clases, un 14.59% (n=20) se asignó en la clase 1 (CL1), la clase 2 (CL2) comprendió un 44,52% (n=61) y la clase 3 (CL3) un 40,87% (n=56) de los participantes. La Clase 1, denominada «Perfeccionismo Insano», reveló puntuaciones altas en la subescala de Discrepancia y bajas en el resto. Los participantes de la Clase 2, identificada como «Perfeccionismo Sano», mostraron unas puntuaciones más elevadas en Altos Estándares y en Orden. Los participantes en la Clase 3, denominada «No Perfeccionismo», revelaron unas puntuaciones bajas en todos los dominios del perfeccionismo. La Figura 1 refleja los tres perfiles de perfeccionismo.

3.3. Validación de los perfiles de clases latentes de perfeccionismo

Los valores del MANCOVA indicaron un efecto significativo para los perfiles latentes de grupo [?Wilk=0,131, F(10, 256)=45,029; p<lt;lt;0,001]. La media y la desviación típica, así como los valores p y el tamaño del efecto para la solución de 3 clases latentes se muestran en la Tabla 4. Atendiendo a las puntuaciones de Discrepancia, no se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en los perfiles latentes. Se encontraron diferentes configuraciones de asociaciones con el perfeccionismo positivo y negativo de la PNPS-12. En concreto, los perfeccionistas «Sanos» puntuaron más alto, comparados con otras clases latentes, en Altos Estándares, Orden y Perfeccionismo Positivo.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

El perfeccionismo es un constructo multidimensional relacionado con el logro de la excelencia y el bienestar. Se expresa como un continuum (Chan, 2007; Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012) de pensamientos y conductas con aspectos positivos y negativos particularmente relevantes en los estudiantes con ACI dado que modulan el logro de la excelencia esperada en ellos (Pyryt, 2007).

Más allá del punto de vista clínico y patológico (Costa, Hausenblas, Oliva, Cuzzocrea, & Larcan, 2016; Donahue, Reilly, Anderson, Scharmer, & Anderson, 2018), este estudio adopta una perspectiva sobre el perfeccionismo que le considera como un rasgo cognitivo considerado irrelevante en la alta capacidad intelectual, intentando diferenciar el perfeccionismo saludable/adaptativo del perfeccionismo no saludable/mal adaptativo. Dado la relación entre perfeccionismo con los objetivos personales y el rendimiento académico y dado que el perfeccionismo se relaciona con su facilitación o inhibición para conseguirlos, es preciso detectar los componentes de los diferentes tipos de perfeccionismo ya que puede permitir la mejor comprensión del estudiante y optimizar su motivación, esfuerzos y regulación ejecutiva, preservando su bienestar y facilitando la consecución del alto rendimiento en ámbitos académicos, cuestión especialmente relevante en la ACI dado que la existencia de una alta potencialidad no asegura la consecución de objetivos de logro relevantes.

Los resultados obtenidos en el presente estudio mediante el análisis de clústers latentes aplicado a los resultados de la administración de las escalas APS-R encuentran una solución de 3 clústers de perfeccionismo similar al modelo de Frost (Frost & al., 1990) o de las escalas APS-R. Esta solución de tres clústers es diferente del modelo de dos dimensiones (Saludable / No saludable) encontrado por Stoeber (2018). En cambio, los resultados son similares a los de Slaney y otros (2001) revelando una estructura de 3 clúster: Clúster 1 (Perfeccionismo No saludable/Mal adaptativo); Clúster 2 (Perfeccionismo saludable/Adaptativo); y Clúster 3 (No Perfeccionismo). En contraste con Mofield y Parker-Peters (2015), los tres Clúster han sido validados, incluso el Clúster 2.

No obstante, emergen algunas diferencias respecto a las puntuaciones que configuran los clústers hallados. El Clúster 1 (Perfeccionismo No saludable/Mal adaptativo) se define por altas puntuaciones en Estándares y Discrepancia, y bajas puntuaciones en Orden (Parker, 2002; Speirs-Neumeister, 2007), pero contrariamente a otros estudios (Chan, 2012; Mofield & al., 2015), que muestran la existencia de altas puntuaciones en todos los componentes. El Clúster 2 (Perfeccionismo saludable/Adaptativo) revela alta puntuación en Estándares y Orden pero no en Discrepancia, corroborando los resultados de Chan (2012) Parker (1997), y sugiriendo que estos estudiantes podrían ser más adaptativos que los incluidos en el Clúster 1. El Clúster 3 (No perfeccionismo), es similar al obtenido por otros investigadores (Chan, 2007; Chan, 2010) mostrando menores puntuaciones que los otros dos grupos en todos los componentes excepto en Discrepancia, no hallando en ella diferencias estadísticamente significativas. Por lo tanto, dada la ausencia en este estudio de diferencias significativas en Discrepancia, este componente no puede ser considerado como un componente diferencial del perfeccionismo No saludable/Mal adaptativo versus el Saludable/Adaptativo, al contrario de lo postulado por Chan (2012).

Los análisis de correlación entre la escala PNPS-R y la APS-R muestran una correlación positiva y significativa entre Orden y Altos Estándares con el Perfeccionismo Positivo; por otra parte, se ha hallado alta correlación entre Discrepancia y el Perfeccionismo Negativo, pero no con el Perfeccionismo Positivo. Además, la Discrepancia muestra una correlación significativa con el Perfeccionismo No saludable/Mal adaptativo y con el Perfeccionismo Saludable/Adaptativo.

Estos resultados sugieren importantes ideas respecto a la necesidad de diferenciar el perfeccionismo positivo del negativo así como del Saludable/Adaptativo respecto del no Saludable/Mal adaptativo en estudiantes con ACI (Chan, 2012). La identificación temprana y la guía de estudiantes perfeccionistas son esenciales con el fin de optimizar su esfuerzo y consecución de la excelencia, así como el logro de objetivos de rendimiento como manifestación de su alto potencial. En suma, es preciso promocionar el perfeccionismo Saludable/Adaptativo para conseguir la excelencia y la eminencia adulta con productos excepcionales ofrecidos por los que la sociedad denomina genios (Chan, 2012).

Los resultados obtenidos facilitan una mayor comprensión de la manifestación del perfeccionismo en la ACI como una de sus variables moduladoras para la expresión del genio en la adultez. Esta cuestión puede tener un impacto relevante en padres, educadores y psicólogos en las escuelas ya que la manifestación del perfeccionismo en la ACI es heterogénea. Algunos estudiantes no revelan perfeccionismo, otros revelan un perfeccionismo saludable y otros muestran una manifestación negativa de este constructo psicológico. En consecuencia, los padres y profesionales de la educación deben promover actividades e intervenciones en las que los componentes del perfeccionismo saludable (alto estándar y orden) estén presentes. La era digital está generando un nuevo escenario en el que niños y adolescentes están rodeados por estímulos, dispositivos y actividades relacionadas con estos que ofrecen una nueva perspectiva para el desarrollo de las habilidades cognitivas y su regulación ejecutiva. Por lo tanto, es preciso esforzarse para comprender mejor este fenómeno y nuevo contexto.

Finalmente, y considerando el rol fundamental de la motivación para la manifestación del alto potencial intelectual, es necesario realizar mayor número de investigaciones que aborden la relación entre la motivación y el perfeccionismo con el fin de promover la óptima expresión del potencial intelectual y el bienestar de los estudiantes con ACI (Fletcher & Speirs-Neumeister, 2012). La consideración de estos aspectos puede mejora la intervención educativa con estudiantes de ACI mediante la implementación de medidas educativas que atiendan a estos y otros aspectos como el de la cultura digital.

Apoyos

Esta investigación ha recibido el apoyo del Ministerio Español de Competitividad con el Proyecto Nacional de Excelencia EDU2016-78440P y del Convenio con la Consejería de Educación, Formación y Empleo del Gobierno Autónomo de La Rioja (España).

Referencias

Akaike, H. (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52, 317-332. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294359

Baker, J.A. (1996). Everyday stressors of academically gifted adolescents. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 7(2), 356-368. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X9600700203

Bennet, G.K., Seashore, H.G., & Wesman, A.G. (2000). DAT-5. Test de Aptitudes Diferenciales. Madrid: TEA.

Castelló, A., & Batlle, C. (1998). Aspectos teóricos e instrumentales en la identificación del alumnado superdotado y talentoso. Propuesta de un protocolo. Faisca Revista Altas Capacidades, 6, 26-66.

Chan, D.W. (2007). Positive and negative perfectionism among Chinese gifted students in Hong Kong: Their relationships to general self-efficacy and subjective well-being. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 31, 77-102. https://doi.org/10.4219/jeg-2007-512

Chan, D.W. (2010). Perfectonism among Chinese gifted and nongifted students in Hong-Kong: The use of the revised almost perfect scale. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34, 68-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235321003400104

Chan, D.W. (2012). Life satisfaction, happiness, and the growth mindset of healthy and unhealthy perfectionists among hong kong chinese gifted students. Roeper Review, 34(4), 224-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2012.715333

Costa, S., Hausenblas, H.A., Oliva, P., Cuzzocrea, F., & Larcan, R. (2016). Maladaptive perfectionism as mediator among psychological control, eating disorders, and exercise dependence symptoms in habitual exerciser. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 77-89. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.004

Damian, L.E., Stoeber, J., Negru, O., & B?ban, A. (2014). Perfectionism and achievement goal orientations in adolescent school students. Psychology in the Schools, 51(9), 960-971. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21794

Damian, L.E., Stoeber, J., Negru-Subtirica, O., & B?ban, A. (2017). On the development of perfectionism: The longitudinal role of academic achievement and academic efficacy. Journal of Personality, 85(4), 565-577. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12261

Dixon, F.A., Lapsley, D.K., & Hanchon, T.A. (2004). An empirical typology of perfectionism in gifted adolescents. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(2), 95-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620404800203

Donahue, J.M., Reilly, E.E., Anderson, L.M., Scharmer, C., & Anderson, D.A. (2018). Evaluating Associations between perfectionism, emotion regulation, and eating disorder symptoms in a mixed-gender sample. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(11), 900-904. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000895

Fletcher, K.L., & Speirs-Neumeister, K.L. (2012). Research on perfectionism and achievement motivation: implications for gifted students. Psychology in the Schools, 49(7), 668-677. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21623

Flett, G.L., Besser, A., & Hewitt, P.L. (2014). Perfectionism and interpersonal orientations in depression: An analysis of validation seeking and rejection sensitivity in a community sample of young adults. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 77(1), 67-85. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2014.77.1.67

Frost, R.O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449-468. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172967

Hewitt, P.L., & Flett, G.L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456-70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

IBM Corp Released (Ed.) (2013). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Leone, E.M., & Wade, T.D. (2017). Measuring perfectionism in children: A systematic review of the mental health literature. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(5), 553-567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1078-8

Lo, Y., Mendell, N.R., & Rubin, D.B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767-778. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/88.3.767

Mofield, E.L., & Parker Peters, M. (2015). The relationship between perfectionism and overexcitabilities in gifted adolescents. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 38(4), 405-427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353215607324

Muñiz, J., Elosua, P., & Hambleton, R.K. (2013). Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests. Psicothema, 25, 151-157. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.24

Muthén, L.K., & Muthén, B.O. (n.d.). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. http://bit.ly/2YI5PWA

Olzewski-Kubilius, P., Subotnik, R.F., & Worrell, F.C. (2015). Repensando las altas capacidades: una aproximación evolutiva. Revista de Educación, 368, 40-65. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2015-368-297

Ortega, N.E., Wang, K.T., Slaney, R.B., Hayes, J.A., & Morales, A. (2014). Personal and familial aspects of perfectionism in latino/a students. The Counseling Psychologist, 42(3), 406-427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012473166

Parker, W.D. (1997). An empirical typology of perfectionism in academically talented children. American Educational Research Journal, 34(3), 545. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163249

Parker, W.D. (2002). Perfectionism and adjustment in gifted children. In Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 133-148). Washington: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-005

Parker, W.D., Portesová, S., & Stumpf, H. (2001). Perfectionism in mathematically gifted and typical czech students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 25(2), 138-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320102500203

Pyryt, M.C. (2007). The Giftedness/perfectionism connection: Recent research and implications. Gifted Education International, 23(3), 273-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940702300308

Ramaswamy, V., DeSarbo, W.S., Reibstein, D.J., & Robinson, W.T. (1993). An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science, 12, 103-124. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.12.1.103.

Rice, K.G., & Richardson, C.M.E. (2014). Classification challenges in perfectionism. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(4), 641-648. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000040

Rice, K.G., Richardson, C.M.E., & Tueller, S. (2014). The Short form of the revised almost perfect scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96(3), 368-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.838172

Roxborough, H.M., Hewitt, P.L., Kaldas, J., Flett, G.L., Caelian, C.M., Sherry, S., & Sherry, D.L. (2012). Perfectionistic Self-presentation, socially prescribed perfectionism, and suicide in youth: A test of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(2), 217-233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00084.x

Sastre-Riba, S. (2013). High intellectual ability: Extracurricular enrichment and cognitive management. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 36(1), 119-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353212472407

Sastre-Riba, S., Pérez-Albéniz, A., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2016). Assessing perfectionism in children and adolescents: Psychometric properties of the almost perfect scale revised. Learning and Individual Differences, 49, 386-392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.022

Schuler, P.A. (2000). Perfectionism and gifted adolescents. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 11(4), 183-196. https://doi.org/10.4219/jsge-2000-629

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics, 6, 461-464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136

Sciove, S.L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52, 333-343. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294360

Shafran, R., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C.G. (2002). Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 773-791. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00059-6

Sironic, A., & Reeve, R.A. (2015). A combined analysis of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS), Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS), and Almost Perfect Scale - Revised (APS-R): Different perfectionist profiles in adolescent high school students. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1471-1483. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000137

Slaney, R., Rice, K., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J.S. (2001). The Revised almost perfect scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 34(3), 130-145. https://doi.org/10.1037/t02161-000

Smith, M.M., & Saklofske, D.H. (2017). The structure of multidimensional perfectionism: Support for a bifactor model with a dominant general factor. Journal of Personality Assessment, 99(3), 297-303. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2016.1208209

Speirs-Neumeister, K. (2007). Perfectionism in gifted students: An overview of current research. Gifted Education International, 23(3), 254-263. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940702300306

Stoeber, J. (2018). Comparing Two short forms of the hewitt-flett multidimensional perfectionism scale. Assessment, 25(5), 578-588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116659740

Torrance, E. (1974). The Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking - Norms -Technical manual research Edition. Princeton, NJ: Personnel. https://doi.org/10.1037/t05532-000

Wang, K.T., Permyakova, T M., & Sheveleva, M.S. (2016). Assessing perfectionism in Russia: Classifying perfectionists with the short almost perfect scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 92, 174-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2015.12.044

Wang, K.T., Puri, R., Slaney, R.B., Methikalam, B., & Chadha, N. (2012). Cultural validity of perfectionism among Indian students. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 45(1), 32-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175611423109

Wang, K.T., Yuen, M., & Slaney, R.B. (2009). Perfectionism, depression, loneliness, and life satisfaction. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(2), 249-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000008315975

Document information

Published on 30/06/19

Accepted on 30/06/19

Submitted on 30/06/19

Volume 27, Issue 2, 2019

DOI: 10.3916/C60-2019-01

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?