Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The worldwide boom in digital video may be one of the reasons behind the exponential growth of MOOCs. The evaluation of a MOOC requires a great degree of multimedia and collaborative interaction. Given that videos are one of the main elements in these courses, it would be interesting to work on innovations that would allow users to interact with multimedia and collaborative activities within the videos. This paper is part of a collaboration project whose main objective is «to design and develop multimedia annotation tools to improve user interaction with contents». This paper will discuss the assessment of two tools: Collaborative Annotation Tool (CaTool) and Open Video Annotation (OVA). The latter was developed by the aforementioned project and integrated into the edX MOOC. The project spanned two academic years (2012-2014) and the assessment tools were tested on different groups in the Faculty of Education, with responses from a total of 180 students. Data obtained from both tools were compared by using average contrasts. Results showed significant differences in favour of the second tool (OVA). The project concludes with a useful video annotation tool, whose design was approved by users, and which is also a quick and user-friendly instrument to evaluate any software or MOOC. A comprehensive review of video annotation tools was also carried out at the end of the project.

1. Introduction

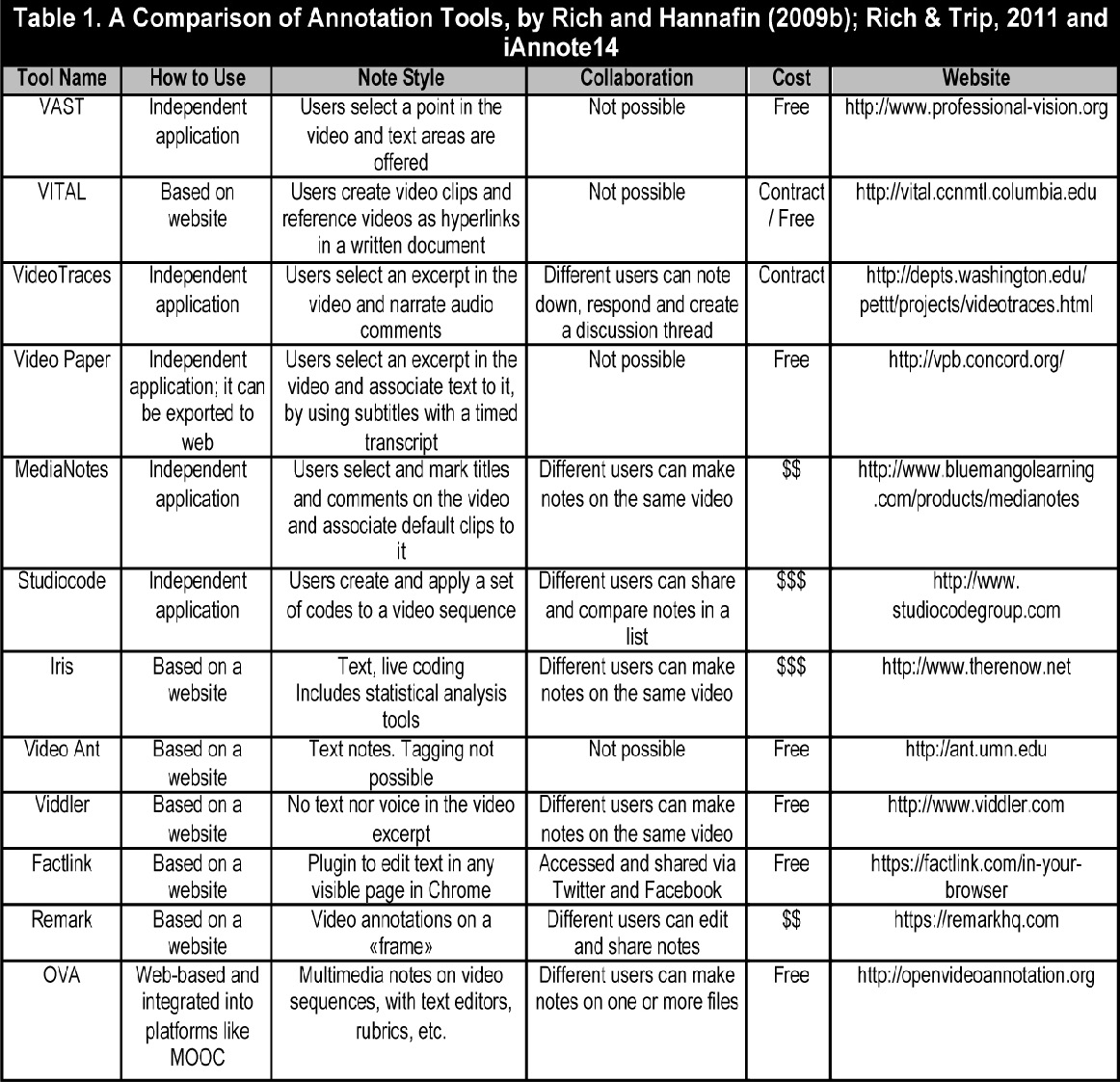

The development of digital video has allowed users greater accessibility; it has made its way into our homes and lives, turning consumer and retail services such as YouTube into a sociological phenomenon. YouTube viewings currently account for an average of 6 million video hours per month1. Clearly much has changed since the Lumière brothers invented cinema (Díaz-Arias, 2009: 64). This development has provided the gateway for developing technologies that allow users to share and collaborate (Computer Supported Collaborative Learning: CSCL). Such technologies also include collaborative video annotation technologies (Yang, Zhang, Su & Tsai, 2011), which have led to the emergence of innovative social projects where video annotation tools are collectively used (Angehrn, Luccini & Maxwell, 2009). The digitization of videos (Bartolomé, 2003) opened up new interactive possibities in education, along with hypermedia (García-Valcarcel, 2008), and has represented a breakthrough for learning and teaching by leaving behind the passive reading of videos (Colasante, 2011). There is a long history of experimental studies on how to apply videos in education (Ferrés, 1992; Cebrián, 1994; Bartolomé, 1997; Cabero, 2004; Area Moreira, 2005; Aguaded and Sánchez, 2008; Salinas, 2013). In the field of teacher training, there are examples related to the concept of microteaching, which has been questioned due to its reductionist approach to teacher initial training. Nevertheless, it was such an effort to come up with a rather rigorous idea of teaching. Leaving aside the theoretical starting point of this paper, there are some recent studies and developments of video annotation tools that, supported by other conceptions of teaching (Schön, 1998; Giroux, 2001), have shown efficacy in meta-evaluations for initial training (Hattie, 2009). The application contexts of the above studies are many and varied, and address processes such as reflection, shared evaluation and collective analysis of classroom situations. Therefore, they have proven to be effective tools for teachers and teacher trainees to collectively analyse everyday teacher practice (Rich & Hannafin, 2009a; Hosack, 2010; Rich & Trip, 2011; Picci, Calvani & Bonaiuti, 2012; Etscheidt & Curran, 2012; Ingram, 2014). In relation to initial training and the development of reflective skills, Orland-Barak & Rachamim (2009) carried out an interesting review and study by comparing different models of reflection using videos as a support. Rich and Hannafin (2009b) conducted another significant review of technological solutions and the potential of video annotation tools for teaching. They conducted a comparative analysis of these tools based on the following criteria: how to use, note style, collaboration, safety, online-offline, format, resource import vs. export, learning curve and cost (free/hiring research teams). We then found an even more extensive review (Rich & Trip, 2011), shown in table 1, which was completed by solutions, presented in the last international workshop on multimedia notes ‘iAnnote14’2.

2. Integrating collaborative annotation tools in MOOC

Video and other related emerging technologies (analysis of big data, ontologies, semantic web, geolocation, multimedia notes, rubric-based assessment, federation technologies, etc.) quickly gained prominence in MOOCs, shaping the core structure of these courses. The appealing and widespread use of videos may have played a role in the boom of MOOCs, prompting a search for new interactive ways to read videos and general contents. It was only recently that MOOCs have incorporated previous experiences and developments on the features of collaborative multimedia annotations; allowing for a more interactive, multimedia learning process, and sharing users’ views on these platforms. This has also provided the gateway for a new model of learning community within the MOOC, which can manage a significant flow of meanings extracted from reading contents and from annotations in different codes, namely: video, text, image and sound notes, as well as hyperlinks and eRubrics (Cebrián-de-la-Serna & Bergman, 2014; Cebrián-de-la-Serna & Monedero Moya, 2014).

These notes can be made in different formats and codes showing contents, such as: annotations in videos, texts, images, maps, charts, etc. as well as annotations created by users. The above possibilities open up a whole new line of new technological developments and research on the dynamic narrative of messages, given the speed with which MOOC platforms and courses are being implemented worldwide. Therefore, we need to innovate in the design and content of video tools based on their new interactive possibilities, in order not to replicate mistakes from the past, when, in the early stage of a new technology, the narrative models of preceding technologies would be incorporated without exploring the interactive potential of the new formats. Something similar happened during the transition from radio messages to television messages, as pointed out by Guo, Kim & Rubin (2014), who conducted a study on the video sessions of four edX courses. They checked the different formats used and concluded that recording cannot be extrapolated to MOOC, because students do not pay enough attention. As a consequence, they suggested a list of recommendations that can be summarized as follows: more interactive and easy- o-edit videos, shorter (6 minutes), and easy-to -share notes. The development of educational software and the possibilities offered by free software have generated a community of developers who share their experience. The fact that these products get feedback from users also constitutes a model of software production; as communities of practice emerge around tools, services and specific platforms such as GitHub3.

The symbiotic relationship between developers and communities of practice has allowed MOOCs to evolve from structured approaches (xMOOCs) to communicative and collaborative approaches (cMOOC)s in their platforms and courses. However, both approaches require new interactive features in the videos. An example of such features is the project here presented, which has been led by the HarvardX team for integration into the edX MOOC, and whose objectives are as follows: on the one hand, designing high-capacity multimedia annotation tools to create multimedia meaning and sharing it with users; and on the other, competence assessment, self-assessment and peer assessment through eRubrics. In order to quickly introduce these changes of great impact, we must count on assessment strategies for end-users to evaluate tools while they are being developed. Tools must be quick and easy to use, in order to collect data that will guide production (technical and content production), even before the beta version emerges. This is why our GTEA group carries out a design, test and evaluation line for educational software, which aims to find a balance between educational innovation and technological innovation, i.e. between generating new environments and users’ usability and satisfaction. The ultimate aim is for new interactive methodologies such as multimedia annotation tools for MOOCs, to be validated by end-users. To do so, we need to create a parallel line of research and evaluation instruments that are reliable and valid for decision-taking when designing educational software. We must take into account all possible elements for software evaluation from the users’ perspective (satisfaction, usability, cost, portability, productivity, accessibility, safety, etc.), in order to examine their ease of use (aka usability), regardless of their context, personal differences, different supports (tablets, mobile phones, computers, etc.).

This paper uses the following definition of usability: ‘the extent to which a product can be used by certain users to achieve specific goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a particular context of use’ (Bevan, 1997). Satisfaction is often seen as a construct within usability studies and instruments, although we believe it is rather the opposite. The ease of use of a tool or service is an element that belongs to the overall user satisfaction. The satisfaction of technological tools and services can even be considered as a sub-category within user satisfaction studies, as shown by studies on students’ satisfaction of university life (Blázquez, Chamizo, Cano & Gutiérrez, 2013). This is a live debate, given the massive presence of technological services and resources, and the digitisation that most communication, teaching, research and administration processes have recently gone through within universities. Both usability and user satisfaction are measured by questionnaires completed by users. We can find usability questionnaires in websites and systems (Bangor, Kortum & Miller, 2008; 2009; Kirakowski & Corbett, 1988; Molich, Ede, Kaasgaard & Karyukin, 2004; Sauro, 2011), satisfaction questionnaires, and questionnaires on both usability and satisfaction (Bargas-Avila, Lötscher, Orsini & Opwis, 2009; McNamaran & Kirakowski, 2011).

3. Methodology

The present project started from the mutual interest shared by our team and HarvardX Annotation Management in creating tools to facilitate meaning processes based on collective multimedia annotations. The general aim of the project was to create a new tool for multimedia annotations specifically designed to respond to the new features of technological progress (e.g. semantic web, annotation ontology, etc.), as well as to the social practices that are currently being developed by users on the Internet (learning in communities of practice, using mobile devices, collaborative work, communication in social networks, creating eRubrics, etc.). The tool is currently integrated into the edX MOOC, and has been in use since January 2014 in the courses offered by HarvardX4. The technological development started from scratch, although it was based on the progress that had been made in the field of multimedia annotations on the Open Annotation Community Group, and taking into account the aforementioned literature as well as other developments by Harvard University. The results presented here are part of a collaborative project and show users’ opinions on the usability and user satisfaction in relation to an instrument designed to assess web tools. Such data is often required to design and improve tools. This is why the methodology used in this paper contrasted end-users’ usability and satisfaction in the Collaborative Annotation Tool (CaTool) (created by Harvard University, 2012), against the added features of the new tool created by the Open Video Annotation project (OVA).

For methodological purposes, the new added features of video annotation were considered as the independent variable. The development had a dual purpose: to serve as a collective multimedia annotation service, and to integrate the new features into the edX MOOC. The present paper will only show the results of assessing the video annotation features that had been added to the edX MOOC. However, this platform hosted the full-featured OVA video annotation, text, sound and quality image (the last two in experimental stages).

The study was divided into two parts: a) The first stage during the 2012-13 academic year, where the Collaborative Annotation Tool (CaTool) was trialled on groups of different subjects in the Faculty of Educational Sciences at the University of Malaga (Spain). The usability and user satisfaction instrument that we had already created for other tools was also tested during this stage. b) The second stage during the 2013-14 academic year, where the usability and user satisfaction instrument designed during the fist stage was improved and applied to two groups from the Degree of Education that shared the same teacher, methods and tasks; we compared two different annotation tools: CaTool and a beta tool that only had the OVA video annotation feature. In the first stage (2012-13) the Collaborative Video Annotation tool was tested in the class within the Education department and on different types of subjects within the degree programme (core subjects, elective subjects, internships, etc.). The tool was federated by our team, and its combination with other tools, such as eRubric and federation technology, had provided interesting features in practice (see Image no.1). The state of the art in relation to the design, creation and assessment of previous video annotation tools was also collected at this stage.

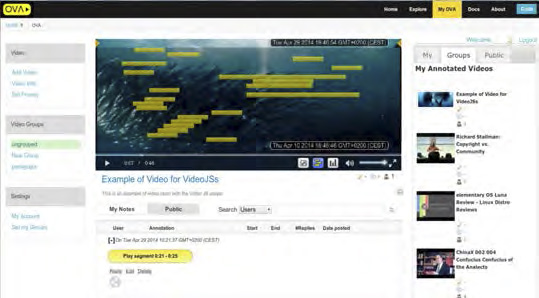

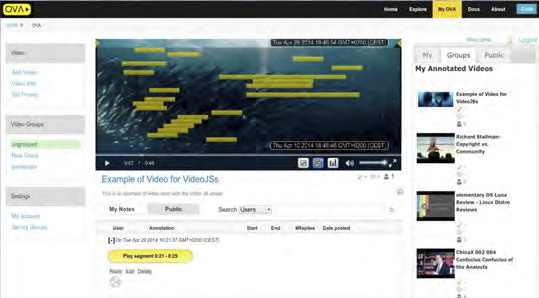

At the second stage, during the second half of 2013, a new Open Video Annotation (OVA)5 was created (image 2), which responded to an interactive and communicative teaching model in the MOOC. The creation and design of this tool was guided by the HarvardX annotation manager, and included the following features: a) Editing entries could be done in a multimedia format (video, text, image, etc.). b) Multimedia annotations could be added within the resource itself (in the video, image, etc.). c) Annotations could be shared and discussed by a large number of users, so that when someone received a message with a note on it, a simple click would take them to that particular note within the resource. d) Editing tags in a database of ontological annotations was possible. As an option, each entry also had the possibility of geolocating. f) Annotations could easily be shared on social networks. eRubrics could be created when editing annotations.

Figure 1: eRubric tool integrated into CaTool annotations.

Figure 2: Multimedia annotation tool.

During the 2013-14 academic year, CaTool and OVA were tested. The test involved the same teacher, methodology, class lab and all the student groups (180 in total) of the mandatory second year technological resources course within the degree of Education in the Faculty of Educational Sciences at the University of Malaga. After this, the enhanced instrument of usability and user satisfaction from stage 1 was used. The first experiment was performed on the CaTool, and the second on a beta tool (a month later); but only on the OVA video annotation feature, and with some limitations (it could only be used with the Chrome browser).

4. Analysis and results

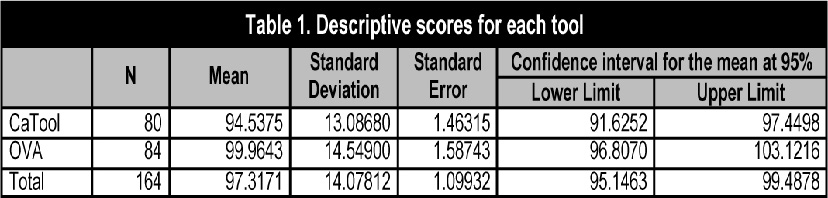

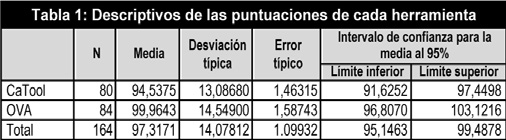

The participant sample consisted of all the students from the aforementioned mandatory course in the Faculty of Educational Sciences who got to work with these tools for the first time. Once they performed the task set by the teacher, they were asked to answer a questionnaire on usability and user satisfaction. The questionnaire consisted of a series of descriptive questions (age, gender, user level, etc.), followed by 26 sentences to be rated on a Likert rating scale of 1 to 5. There were direct sentences (1=the worst; 5=the best) as well as indirect sentences (1= the best; 5=the worst). As for usability, there were 17 sentences: 5 direct and 12 indirect. For user satisfaction there were 9: 7 direct and 2 indirect. The order of the sentences in the questionnaire was random, in order to avoid answering without reading. There was an open question at the end, for students to write free comments. The average response time was 4 minutes. The questionnaire was filled out online by using LimeSurvey, while data was analyzed by using the SPSS (version 20). For analysis purposes, we ensured answers had to be thought through, and sentences could not be rated by simply filling out the questionnaire. To this end, we detected 16 answers that marked similar values ??in blocks corresponding to direct and indirect sentences, so they were therefore considered as non-valid answers. We carried out the y=6-x transformation in the values ??of indirect sentences, so that calculations could not be counteracted.

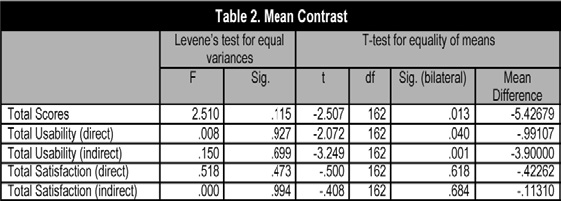

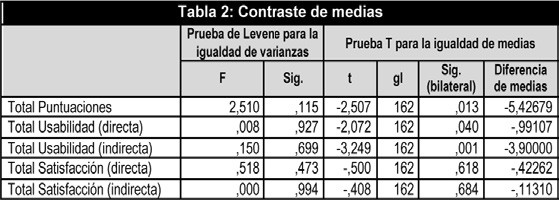

Significant differences were found in favour of OVA among the means of the questionnaire. When analysing the questionnaire by blocks, significant differences were also found in the usability blocks, but not in the user satisfaction blocks (table 2).

The contrast of the usability and satisfaction instrument between the two tools throws up significant differences in favour of OVA in the following items: ‘I found the application to be pleasant’, ‘I found the application exhausting to use’, ‘The application does not need explaining to be used’, I needed help to access the application’, ‘I ran into technical problems’, ‘It requires expert help’, ‘The response time in the interaction is slow’.

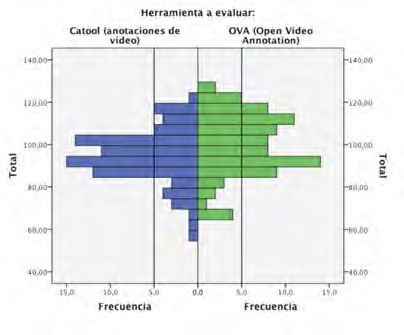

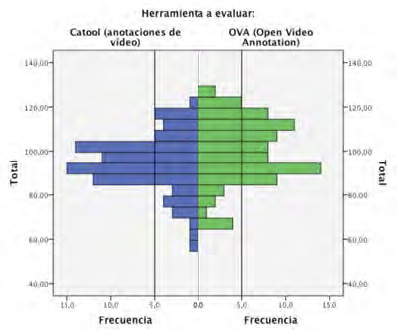

Figure 3: Histograms of total scores on the two tools.

Graph 1 shows the histograms of the total scores for each tool. It shows that, from the 105 score onwards, there are more ratings for OVA than for CaTool, while the opposite goes for scores under 105. According to their comments, respondants support the questionnaire results: they consider these tools to be easy, useful and innovative. The negative aspects were mainly attributed to technical issues: Internet access, slow server or browser limitations in the beta version.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The potential of the video digitalizing process has been foreseen for a long time, along with new teaching processes at universities (Aguaded & Macías, 2008: 687), except that nowadays we look forward to even further possibilities that go beyond past predictions. Socialization and distribution of information, free access to premium content, networks and learning communities to share and generate new ways of learning, the technological development of the Internet (augmented reality, mobile technology, wearable, network capacity, etc.) are forcing universities to respond to new challenges.

MOOC platforms are not immune to these changes, and will soon incorporate experiences and developments in the area of collective multimedia annotations. Innovations find in these massive platforms an ideal setting for developing, testing and experimenting with educational research. Certainly, we consider this new environment as an ideal setting for conducting new experiments, studies and educational projects such as the one put forward here. The present project has shown that collective multimedia annotations are generally highly-rated by students when they are easy to use (as observed in the aforementioned mean differences), and when displaying certain features that are fashionable amongst the young. For instance, features related to mobility, social networks, collective interaction and broadcast of shared meanings, as could be observed in the best rated features and in the open essay answers when the two tools were compared. These features were added to the new Open Video Annotation (OVA) tool, which aims to be in line with university students’ symbolic and communicative competence. Students should be therefore more critical and prepared for what Castell (2012: 23-24) defines as mass self-communication. He considers this to be vital in symbolic construction, as it mainly depends on «the created frameworks, i.e. the fact that the transformation of the communication environment directly affects the way in which meaning is constructed».

We believe that collective multimedia annotation has many educational possibilities in university teaching. Some of these possibilities go beyond the existing format, reaching the aforementioned ‘created framework’ nowadays represented by MOOCs. Their application and research can be interesting in further educational settings beyond those studied in this project, such as: a) Blended learning models currently developed at universities, which use materials and resources to support teaching; b) Learning objects with multimedia annotations and semantic web (García-Barriocanal, Sicilia, Sánchez-Alonso & Lytras, 2011); c) Supervision during the Practicum (Miller & Carney, 2009) with ePortfolios (electronic portfolios), filled with multimedia proof of learning and where the meanings given to annotations can be shared. d. Dissemination of scientific knowledge, as suggested by Vázquez-Cano (2013: 90), by combining the written format with the video-article and the scientific pill. Such combination would provide scientific production with more visibility, broadcast and flow of exchange. All the above contexts and experiences are innovative and consistent with the practice that we wish to widely implement in universities, thus representing a strong leadership in the knowledge society.

Support and notes

The collaborative project was entitled Open Video Annotation Project (2012-2014) (http://goo.gl/51W37d) and was made possible through the joint funding of institutions such as: Talentia scholarships and Gtea Group (http://gtea.uma.es) PAI SEJ-462 Andalusian Regional Government, University of Malaga and Center for Hellenic Studies –CHS– (Harvard University) (http://chs.harvard.edu (09-07-2014).

1 YouTube Statistics (http://goo.gl/AlYrCL) (09-07-2014).

2 International Workshop on Multimedia Annotations ‘iAnnote14’, San Francisco, California (USA), April 3-6, 2014 http://iannotate.org (09-07-2014).

3 Open Source Platform http://github.com.

4 The first course using OVA was ‘Poetry in America: Whitman’, in edX Harvard University http://goo.gl/I9bupN (09-07-2014).

5 OVA Tool (http://openvideoannotation.org) (09-07-2014).

References

Aguaded, I. & Sánchez, J. (2008). Niños adolescentes tras el visor de la cámara: expe-riencias de alfabetización audiovisual. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 14, 293-308.

Aguaded, J. & Macías, Y. (2008). Televisión universitaria y servicio público. Co-municar, 31, XVI, 681-689. (http://doi.org/cd4fkw).

Angehrn, A., Luccini, A. & Maxwell, K. (2009). InnoTube: A Video-based Connection Tool Supporting Collaborative Innovation. Interactive Learning Environments, 17, 3, 205-220. (http://doi.org/bw48vv).

Area, M. (2005). Los criterios de calidad en el diseño y desarrollo de materiales didácticos para la www. Comunicación y Pedagogía, 204, 66-72.

Bangor, A., Kortum, P.T. & Miller, J.T. (2008). An Empirical Evaluation of the System Usability Scale. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24(6), 574-594.

Bangor, A., Kortum, P.T. & Miller, J.T. (2009). Determining What Individual SUS Scores Mean: Adding an Adjective Rating Scale. Journal of Usability Studies. 4 (3), 114-123.

Bargas, J.A., Lötscher, J., Orsini, S. & Opwis, K. (2009). Intranet Satisfaction Questionnaire: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Measure User Satisfaction with the Intranet. Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 1241-1250. (http://doi.org/b39md8).

Bartolomé, A. (1997). Uso interactivo del vídeo. In J. Ferrés & P. Marques (Coord.), Comunicación educativa y nuevas tecnologías. Barcelona: Praxis. 320 (1-13).

Bartolomé, A. (2003). Vídeo digital. Comunicar, 21, 39-47. (http://goo.gl/MDcYOt) (29-04-2014).

Bevan, N. (1997). Quality and Usability: A New Framework. In Van Veenendaal, E. & McMullan, J. (Eds.), Achieving Software Product Quality. Netherlands: Tutein Nolthenius, 25-34.

Blázquez, J.J., Chamizo, J., Cano, E. & Gutiérrez, S. (2013). Calidad de vida universitaria: Identificación de los principales indicadores de satisfacción estudiantil. Revista de Educación, 362, 458-484. (http://doi.org/tp5).

Cabero, J. (2004). El diseño de vídeos didácticos. In J. Salinas, J. Cabero & I. Aguaded (Coords.), Tecnologías para la educación: diseño, producción y evaluación de medios para la formación docente (PP. 141-156). Madrid: Alianza.

Castells, M. (2012). Redes de indignación y esperanza. Madrid: Alianza.

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M. & Bergman, M. (2014). Formative Assessment with eRubrics: an Approach to the State of the Art. Revista de Docencia Universitaria. 12, 1, 23-29. (http://goo.gl/A4cpaa).

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M. & Monedero, J.J. (2014). Evolución en el diseño y fun-cionalidad de las rúbricas: desde las rúbricas «cuadradas» a las erúbricas federadas. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 12, 1, 81-98. (http://goo.gl/xNhnqR).

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M. (1994). Los vídeos didácticos: claves para su producción y evaluación. Pixel Bit. Sevilla, 1, 31-42. (http://goo.gl/w3Ayi6).

Colasante, M. (2011). Using Video Annotation to Reflect on and Evaluate Physical Education Pre-service Teaching Practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(1), 66-88. (http://goo.gl/f2HfZB).

Díaz-Arias, R. (2009). El vídeo en el ciberespacio: usos y lenguaje. Comunicar, 33, 17, 63-71. (http://doi.org/ftt5qr).

Etscheidt, S. & Curran, C. (2012). Promoting Reflection in Teacher Preparation Pro-grams: A Multilevel Model. Teacher Education and Special Education 35(1) 7-26. (http://doi.org/dk53x2).

Ferrés, J. (1992). Vídeo y educación. Barcelona: Paidós.

García-Barriocanal, E., Sicilia, M.A., Sánchez-Alonso, S. & Lytras, M. (2009). Se-mantic Annotation of Video Fragments as Learning Objects: A Case Study with YouTube Videos and the Gene Ontology. Interactive Learning Environments, 19, 1, 25-44. (http://doi.org/b2pkpf).

García-Valcárcel, A. (2008). El hipervídeo y su potencialidad pedagógica. Revista Lati-noamericana de Tecnología Educativa (RELATEC), 7, 2, 69-79.

Giroux, H.A. (2001). Cultura, política y práctica educativa. Barcelona: Graó.

Guo, P., Kim, H. & Rubin, R. (2014). How Video Production Affects Student En-gagement: An Empirical Study of MOOC Videos. Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning @ scale conference (pp. 41-50. March 4-5, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. (http://doi.org/tp6).

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hosack, B. (2010). VideoANT: Extending Online Video Annotation Beyond Content Delivery. TechTrends, 54, 3, 45-49.

Ingram, J. (2014). Supporting Student Teachers in Developing and Applying Pro-fessional Knowledge with Videoed Events. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(1), 51-62. (http://doi.org/tp7).

Kirakowski, J. & Corbett, M. (1988). Measuring User Satisfaction. 4ª Conference of the British Computer Society Human-Computer Interaction Specialist Group, 329-338.

McNamara, N. & Kirakowski, J. (2011). Measuring User-satisfaction with Electronic Consumer Products: The Consumer Products Questionnaire. International Journal Human-Computer Studies. 69, 375-386. (http://doi.org/d5xzqn).

Miller, M. & Carney, J. (2009). Lost in Translation: Using Video Annotation Software to Examine How a Clinical Supervisor Interprets and Applies a State-mandated Teacher Assessment Instrument. The Teacher Educator, 44(4), 217-231, (http://doi.org/dhj2bv).

Molich, R., Ede, M.R., Kaasgaard, K. & Karyukin, B. (2004). Comparative Usability Evaluation. Behaviour & Information Technology, 23(1), 65-74.

Orland-Barak, L. & Rachamim, M. (2009). Simultaneous Reflections by Video in a Second-order Action Research-mentoring Model: Lessons for the Mentor and the Mentee. Reflective Practice, 10, 5, 601-613. (http://doi.org/db82mr).

Picci, P., Calvani, A. & Bonaiuti, G. (2012). The Use of Digital Video Annotation in Teacher Training: The Teachers’ Perspective. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 600-613. (http://doi.org/tp8).

Rich, P. & Trip, T. (2011). Ten Essential Questions Educators Should Ask When Using Video Annotation Tools. TechTrends, 55, 6, 16-24.

Rich, P. J., & Hannafin, M. (2009a). Scaffolded Video Self-analysis: Discrepancies between Preservice Teachers’ Perceived and Actual Instructional Decisions. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 21(2), 128-145.

Rich, P.J. & Hannafin, M. (2009b). Video Annotation Tools. Technologies to Scaffold, Structure, and Transform Teacher Reflection. Journal of Teacher Education, 60, 1, 52-67. (http://doi.org/dzdv4n).

Salinas, J. (2013). Audio y vídeo Podcast para el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras en la formación docente inicial. IV Jornadas Internacionales de Campus Virtuales. 14-15 Febrero. Universidad de las Islas Baleares. (http://goo.gl/EHq2Jo) (29-04-2014).

Sauro, J. (2011). Measuring Usability with the System Usability Scale (SUS) (http://goo.gl/63krpp) (29-04-2014).

Schön, D.A. (1998). El profesional reflexivo: ¿cómo piensan los profesionales cuando actúan? Barcelona: Paidós.

Vázquez-Cano, E. (2013). El videoartículo: nuevo formato de divulgación en revistas científicas y su integración en MOOC. Comunicar, 41, XXI, 83-91.(http://doi.org/tnk).

Yang, S., Zhang, J., Su, A. & Tsai, J. (2011). A collaborative multimedia annotation tool for enhancing knowledge sharing in CSCL. Interactive Learning Environments 19, 1, 45-62. (http://doi.org/cdtxd7).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El auge del vídeo digital a nivel mundial puede ser una de las causas del crecimiento exponencial de los MOOC. Las evaluaciones de los MOOC recomiendan una mayor interacción multimedia y colaborativa. Siendo los vídeos unos de los elementos destacados en estos cursos, será interesante trabajar en innovaciones que permitan una mayor capacidad a los usuarios para interactuar con anotaciones multimedia y colaborativas dentro de los vídeos. El presente artículo es parte del proyecto de colaboración, cuyo objetivo principal fue «El diseño y creación de herramientas de anotaciones multimedia para mejorar la interactividad de los usuarios con los contenidos». En este artículo mostraremos la evaluación de dos herramientas como fueron Collaborative Annotation Tool (CaTool) y Open Video Annotation (OVA) esta última desarrollada por el proyecto e integrada en el MOOC de edX. El proyecto abarcó dos cursos académicos (2012-14) y se aplicó un instrumento de evaluación en diferentes grupos de la Facultad de Educación a un total de 180 estudiantes. Se compararon los datos obtenidos entre ambas herramientas con contrastes de media, resultando diferencias significativas a favor de la segunda herramienta. Al concluir el proyecto se dispone de una herramienta de anotaciones de vídeo con diseño validado por los usuarios; además de un instrumento sencillo y rápido de aplicar para evaluar cualquier software y MOOC. Se realizó también una revisión amplia sobre herramientas de anotaciones de vídeos.

1. Introducción

El desarrollo del vídeo digital ha permitido mayor accesibilidad a los usuarios, acomodándose con facilidad en los hogares y nuestras vidas, y encontrando en servicios de distribución y consumo como YouTube todo un fenómeno sociológico. En la actualidad la lectura diaria de vídeo en esta plataforma muestra una media de seis millones de horas de vídeo al mes1. Esto representa un cambio de consumo de vértigo si tomamos la perspectiva desde los hermanos Lumière hasta nuestros días en YouTube (DíazArias, 2009: 64). Esta realidad ha abonado el desarrollo de tecnologías, que permiten a los usuarios compartir y colaborar (Computer Supported collaborative Learning: CSCL), dentro de las cuales se encuentran las tecnologías de anotaciones de vídeo colaborativas (Yang, Zhang, Su & Tsai, 2011), que ha facilitado el surgimiento de innovadores proyectos sociales donde se utilizan las herramientas de vídeoanotaciones de forma colectiva (Angehrn, Luccini & Maxwell, 2009). Con la digitalización de los vídeos (Bartolomé, 2003) se abrieron también nuevas posibilidades interactivas e hipermedia en educación (GarcíaValcárcel, 2008), representando todo un avance para el aprendizaje y la enseñanza al permitir abandonar la lectura pasiva de los vídeos (Colasante, 2011). En la actualidad se dispone de una larga trayectoria de experimentación y estudios sobre la aplicación de los vídeos en la educación (Ferrés, 1992; Cebrián, 1994; Bartolomé, 1997; Cabero, 2004; Area, 2005; Aguaded & Sánchez, 2008; Salinas, 2013). Dentro del área de la formación inicial de enseñantes existen experiencias que se inician con los «microteaching» muy cuestionados en su momento por su enfoque reduccionista para la formación inicial de docentes, pero que significó un esfuerzo por plantear una investigación más rigurosa de la enseñanza. Con posterioridad y abandonando en gran parte el marco teórico de partida, existen recientes estudios y desarrollos de herramientas de anotaciones de vídeo que apoyados en otras concepciones de la enseñanza (Schön, 1998; Giroux, 2001) han demostrado su eficacia en las evaluaciones de metaanálisis realizadas para la formación inicial (Hattie, 2009). Los contextos de aplicación de estos trabajos son muchos y abordan procesos como la reflexión, la evaluación compartida y el análisis colectivo de situaciones de aula. Demostrando que son unas herramientas eficaces para que los docentes en servicio y formación inicial analicen sus prácticas de forma colectiva (Rich & Hannafin, 2009a; Hosack, 2010; Rich & Trip, 2011; Picci, Calvani & Bonaiuti, 2012; Etscheidt & Curran, 2012; Ingram, 2014). Dentro de la formación inicial y especialmente del desarrollo de capacidades reflexivas, OrlandBarak y Rachamim (2009) realizan una interesante revisión y estudio comparando diferentes modelos de reflexión utilizando los vídeos como soporte. El trabajo de Rich y Hannafin (2009b) es otra significativa revisión de estas soluciones tecnológicas y las posibilidades que ofrecen las herramientas de anotaciones de vídeo para la enseñanza. En su trabajo recogen un análisis comparativo con los siguientes criterios: modo de uso, estilo de anotación, colaboración, seguridad, onlineoffline, formatos, importación vs. exportación de recursos, curva de aprendizaje y coste (libre y con contratos a equipos de investigación). Con posterioridad encontramos otra revisión aún más amplia (Rich & Trip, 2011) que recogemos en el cuadro 1, y a las que añadimos otras soluciones presentadas en el último workshop internacional sobre anotaciones multimedia «iAnnote14»2.

2. La integración de herramientas de anotaciones colaborativas en los MOOC

No es extraño que los vídeos y las tecnologías emergentes asociadas (análisis de big data, ontologías, web semántica, geolocalización, anotaciones multimedia, evaluación de competencias por erúbricas, tecnologías de federación…) tomaran protagonismo rápidamente en los MOOC, configurando la estructura medular de sus cursos. Puede ser que este atractivo y la práctica generalizada de vídeos haya influido en el auge que han tomado en un primer momento los MOOC, y que han obligado en poco tiempo y con gran necesidad, a la búsqueda de nuevas lecturas más interactivas en sus vídeos y contenidos en general. Ha sido más recientemente cuando se han incorporado en los MOOC todas las experiencias y desarrollos producidos con anterioridad sobre las funciones de anotaciones multimedia colaborativas. Permitiendo un proceso de aprendizaje más interactivo, multimedia y compartido de las interpretaciones que realizan sus usuarios en estas plataformas. Esto está permitiendo hoy el desarrollo de un modelo de comunidades de aprendizaje dentro de los MOOC, que intercambian un importante flujo de significados producidos por la lectura de los contenidos, y mediante anotaciones con diferentes códigos: anotaciones de vídeo, texto, imagen y sonido, hipervínculos y erubricas (Cebrián de la Serna & Bergman, 2014; Cebrián de la Serna & Monedero Moya, 2014).

Estas anotaciones pueden realizarse dentro de los diferentes formatos y códigos que muestren los contenidos como serían: anotaciones dentro de los vídeos, de los textos, de las imágenes, mapas, gráficos… y sobre otras anotaciones creadas por los usuarios. Sin duda, estas posibilidades abren toda una línea de nuevos desarrollos tecnológicos e investigaciones en el futuro inmediato sobre la narrativa de los mensajes, especialmente dinámica y creciente, dada la velocidad con la que se están implementando las plataformas y cursos MOOC en todo el mundo. De tal forma, que debemos innovar en el diseño de contenidos y de herramientas de vídeos, según estas nuevas posibilidades interactivas, para no cometer el mismo error como ha sucedido en otras ocasiones, cuando en los primeros momentos de aparecer una nueva tecnología se incorporaban los modelos narrativos de las anteriores, sin explotar las posibilidades interactivas de los nuevos formatos. Caso similar ocurrió con el paso en la construcción de mensajes de la radio a la televisión, como nos recuerdan Guo, Kim y Rubin (2014), quienes realizaron un estudio de las sesiones de los vídeos de cuatro cursos en edX, comprobando los distintos formatos utilizados, y concluyendo que no puede trasladarse la grabación de clase tal cual a los MOOC, porque los estudiantes no muestran gran capacidad de atención. Por lo que los autores proponen una lista de recomendaciones que podríamos resumir en vídeos más cortos (seis minutos), más interactivos y fáciles de editar y compartir anotaciones. El desarrollo de software educativo y las posibilidades que ofrece el software libre han propiciado conjuntamente una comunidad de desarrolladores que comparten componentes y desarrollos. Viene siendo también un modelo de producción de software que estos productos se retroalimenten con los usuarios, constituyéndose en comunidades de prácticas alrededor de las herramientas, servicios y plataformas específicas como por ejemplo GitHub3.

Esta simbiosis estrecha entre comunidades de desarrolladores y comunidades de prácticas ha permitido evolucionar a los MOOC desde enfoques más estructurados de sus plataformas y cursos (xMOOC) a otros más comunicativos y colaborativos (cMOOC). No obstante, ambos planteamientos reclaman nuevas funciones interactivas en los vídeos. Como el proyecto que se presenta aquí, dirigido por el equipo de HarvadX para su integración en el MOOC de edX, y que tuvo como objetivos: por un lado, la creación de herramientas de anotaciones multimedia de gran capacidad para crear significados multimedia y el intercambio de las mismas entre los usuarios; y por otro lado, la evaluación por competencias, la autoevaluación y la evaluación de pares por medio de erúbricas. Para introducir estos cambios de especial calado y con gran rapidez es necesario disponer de estrategias e instrumentos de evaluación de los usuarios finales mientras se desarrollan las herramientas, que sean sencillas y rápidas para recoger datos que orienten la producción (técnica y de contenidos), incluso antes de que surjan como versiones beta. Por tal motivo, nuestro grupo GTEA lleva una línea de diseño, experimentación y evaluación de software educativo, que pretende buscar un equilibrio entre la innovación educativa y la innovación tecnológica, entre la producción de nuevos entornos y la usabilidad y satisfacción de usuarios. De tal forma, que la búsqueda de nuevas metodologías más interactivas como es el caso de la producción de herramientas de anotaciones multimedia para los cursos MOOC, esté validada por los usuarios finales. Para ello, hemos necesitado crear una línea paralela de instrumentos de investigación y evaluación que fueran fiables y válidos para la toma de decisiones en la producción de software educativo. Sin agotar todos los elementos posibles para la evaluación de software desde la perspectiva de uso (satisfacción, usabilidad, coste, portabilidad, productividad, accesibilidad, seguridad…), pero sí para conocer la facilidad de uso o usabilidad que manifiestan los usuarios, no importa sus condiciones contextuales, diferencias personales, los diferentes soportes que utilicen (tabletas, móviles, ordenadores de mesa…), etc.

Partimos del concepto de usabilidad, según la norma ISO 924111 recogida en Bevan (1997): «el grado en que un producto puede ser usado por determinados usuarios para conseguir objetivos específicos con efectividad, eficiencia y satisfacción en un contexto de uso específico». Por su parte, satisfacción suele considerarse como un constructo dentro de los estudios e instrumentos de usabilidad, cuando sería todo lo contrario. La facilidad de uso de una herramienta o servicio es un elemento de la satisfacción general de los usuarios. Incluso la satisfacción de herramientas y servicios tecnológicos, suelen ser subcategorías de los estudios de satisfacción de los usuarios. Como así se aplica en los estudios de satisfacción de la vida universitaria por los estudiantes (Blázquez, Chamizo, Cano & Gutiérrez, 2013). Actualmente de mucha relevancia por la presencia masiva de servicios y recursos tecnológicos, como de la digitalización que sufren la mayoría de los procesos de comunicación, de enseñanza, investigación y administración en las universidades. Tanto la usabilidad como la satisfacción del usuario se miden mediante cuestionarios contestados por usuarios. Pudiéndose encontrar cuestionarios de usabilidad de sitios web y de sistemas (Bangor, Kortum & Miller, 2008, 2009; Kirakowski & Corbett, 1988; Molich, Ede, Kaasgaard & Karyukin, 2004; Sauro, 2011), como cuestionarios sobre satisfacción, a la vez que cuestionarios de usabilidad y satisfacción conjuntamente (Bargas, Lötscher, Orsini & Opwis, 2009; McNamaran & Kirakowski, 2011).

3. Metodología

El proyecto parte del interés mutuo por nuestro equipo y la dirección de anotaciones en HarvadX por crear herramientas conjuntamente que faciliten los procesos de significación mediante las anotaciones multimedia colectivas. El proyecto tuvo como objetivo general la realización de una nueva herramienta de anotaciones multimedia que respondiera en su diseño a las nuevas características del avance tecnológico (ejemplo, la web semántica, la ontología de anotaciones…), como de las prácticas sociales que actualmente desarrollan los usuarios en Internet (aprendizaje en comunidades de prácticas, uso de dispositivos móviles, trabajo colaborativo, comunicación en redes sociales, elaboración de erúbricas, etc.). En estos momentos, la herramienta está integrada en el MOOC de edX, y se ha comenzado a utilizar a partir del mes de enero del 2014 en los cursos que oferta HarvardX4. Para el desarrollo tecnológico se partió desde cero, pero teniendo en cuenta lo que se había avanzado en este campo de las anotaciones multimedia en Open Annotation Community Group; así como, considerando las referencias de la literatura ya citada anteriormente, como de otros desarrollos generados desde la misma Harvard University. Los resultados que se presentan aquí son partes de este proyecto de colaboración, y muestra los resultados en la opinión sobre la usabilidad y satisfacción por los usuarios desde un instrumento creado para evaluar herramientas web. Datos necesarios para el diseño y mejora en la creación de herramientas. Esta es la razón por la cual, la metodología seguida comparó la usabilidad y satisfacción de los usuarios finales en Collaborative Annotation Tool (CaTool) creada por Harvard University (2012), frente a las funcionalidades añadidas a la nueva herramienta creada en el proyecto Open Video Annotation (OVA).

Considerando, por tanto, estas nuevas funciones añadidas de vídeo anotaciones como variable independiente en la metodología. Si bien, el desarrollo creado consiguió una doble finalidad, servir esta herramienta como servicio de anotaciones multimedia colectivas, a la vez que, integrar sus nuevas y diferentes funciones dentro del MOOC de edX. Aquí solo se presentan los resultados de la evaluación en las funciones de anotaciones de vídeo añadidas al MOOC de edX; si bien, en esta plataforma se instalaron todas las funciones de Open Video Annotation (OVA): anotaciones de vídeo, texto, sonido e imagen de calidad (estas dos últimas en fases experimental).

La realización de la experiencia que se muestra aquí tuvo dos partes: a) Una primera fase durante el curso 201213 donde se experimentó la herramienta Collaborative Annotation Tool (CaTool) en grupos de asignaturas diferentes de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación de la Universidad Málaga. También se puso a prueba el instrumento de usabilidad y satisfacción que teníamos ya creado para otras herramientas; b) En una segunda fase durante el curso 201314 se mejoró el instrumento de usabilidad y satisfacción pasado en la primera fase, y se aplicó a dos grupos del Grado de Pedagogía con el mismo docente, metodología y tareas, solo que comparando dos herramientas de anotaciones diferentes: CaTool y una herramienta beta solo con la función de vídeo anotaciones de OVA. Veamos estas fases más detenidamente: en una primera fase y durante el curso 201213 se experimentó en el Grado de Pedagogía y en diferentes asignaturas (troncales, optativas, prácticas externas…) la herramienta de Anotaciones de Vídeo Colaborativa (CaTool). Esta herramienta fue federada por nuestro equipo y con la combinación de otras herramientas como la erúbrica y la tecnología de federación han proporcionado una interesante combinación de funcionalidades en la práctica (gráfico 1). También se recogió en esta fase el estado del arte en cuanto al diseño, creación y evaluación de otras herramientas de anotaciones de vídeos existentes hasta la fecha.

En una segunda fase y durante el segundo semestre del año 2013 se creó una nueva herramienta Open Video Annotation (OVA)5 (gráfico 2) que respondiera a un modelo pedagógico más interactivo y comunicativo en los MOOC. Se planteó el diseño y creación bajo la dirección del director de anotaciones de HarvardX, con las funciones siguientes: a) Edición de anotaciones en formato multimedia (vídeo, texto, imagen, etc.); b) Que las anotaciones multimedia pudieran realizarse dentro del mismo recurso (dentro del vídeo, de la imagen...); c) Que las anotaciones pudieran compartirse y comentarse por un gran número de usuarios, de modo que cuando alguien recibiera un mensaje con una anotación, con un solo clic le llevase a la anotación específica realizada dentro del recurso; d) Editar etiquetas dentro de una base de datos de anotaciones ontológicas; e) De forma opcional, que cada anotación tuviera la posibilidad de geolocalización; f) Que las anotaciones pudieran compartirse fácilmente por las redes sociales; g) Que en la edición de las anotaciones pudieran crearse erúbricas.

Figura 1: Herramienta erúbrica integrada en anotaciones CaTool.

Figura 2: Herramienta de anotaciones multimedia.

Durante el curso 2013-14 se experimentaron las dos herramientas (CaTool y Ova) con el mismo docente, metodología, laboratorio de clase y todos los grupos de estudiantes (180 en total) de la troncal Recursos Tecnológicos (segundo curso) del Grado de Pedagogía de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación de la Universidad de Málaga. Tras finalizar la experiencia se pasó el mismo instrumento de usabilidad y satisfacción mejorado de la fase I. La primera experiencia se realizó con la herramienta CaTool, y transcurrido un mes se experimentó con una herramienta beta, solo con la función de vídeo anotaciones de OVA y algunas limitaciones (solo podía utilizarse con el navegador Chrome).

4. Análisis y resultados

La muestra participante está formada por todos lo estudiantes de la mencionada asignatura troncal de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación que trabajaron con estas herramientas por primera vez. Una vez que han realizado la misma tarea encargada por el profesor se les pidió que contestaran al cuestionario de usabilidad y satisfacción. El cuestionario estaba conformado de unas preguntas descriptivas (edad, género, nivel de usuario, etc.), seguido de 26 sentencias a valorar en una escala Likert de uno a cinco. Había sentencias enunciadas de forma directa (uno como lo peor, a cinco como lo mejor) y sentencias indirectas (uno como lo mejor, a cinco como lo peor). Sobre usabilidad había 17 sentencias, cinco en forma directa y 12 en forma indirecta, y de satisfacción hay nueve: siete de forma directa y dos de forma indirecta. El orden de las sentencias en el cuestionario era aleatorio, para evitar respuestas sin leer los enunciados. Al final se dejó una pregunta abierta para que pudieran escribir las observaciones que consideraran. El tiempo medio para responder era de cuatro minutos. El cuestionario se rellenaba en línea con ayuda de LimeSurvey, en tanto que los datos obtenidos se analizaron con el SPSS (versión 20). Para su análisis previamente hemos comprobado que las respuestas eran reflexivas, y no se habían contestado por el simple hecho de rellenar el cuestionario. A tal efecto, hemos detectado 16 respuestas que han marcado valores semejantes en los bloques correspondientes a sentencias directas y en los de sentencias indirectas, considerándolas como respuestas no válidas. Hemos realizado la transformación y=6x en los valores correspondientes a las sentencias indirectas, para que no se contrarresten en los cálculos.

Hemos encontrado diferencias significativas a favor de OVA entre las medias del total del cuestionario. Estudiándolo por bloques también hay diferencias significativas en los bloques de usabilidad, pero no en los de satisfacción.

La comparación del mismo instrumento de usabilidad y satisfacción entre las dos herramientas nos da diferencias significativas a favor de OVA en los ítems siguientes: «La aplicación me resultó agradable»; «Fue agotador utilizar la aplicación»; «Se puede usar sin necesidad de explicaciones previas»; «He necesitado ayuda para acceder»; «Me encontré con problemas técnicos»; «Requiere ayuda de un experto. El tiempo de respuesta en la interacción es lento».

Figura 3: Histogramas del total de puntuaciones en las dos herramientas.

En el gráfico 1 se muestran los histogramas correspondientes al total de las puntuaciones para cada una de las herramientas, donde se observa que a partir de la puntuación total de 105 hay más valoraciones para OVA que para CaTool, y ocurre lo contrario para las valoraciones inferiores a 105. De las observaciones escritas por los encuestados apoyan los resultados obtenidos en el análisis del cuestionario pudiéndose resumir: en general, todos valoran estas herramientas como fáciles, útiles e innovadoras. Los aspectos negativos los atribuyen principalmente a problemas de índole técnico: acceso a Internet, lentitud del servidor en el que se alojan o limitaciones por el navegador en la versión beta.

5. Discusión y conclusiones

Hace tiempo que se adelantaban las posibilidades que abrirían la digitalización del vídeo y los procesos de enseñanza para las universidades (Aguaded & Macías, 2008: 687), solo que actualmente cuando miramos hacia adelante nos encontramos con otras posibilidades que superan lo imaginable tiempo atrás. La socialización y distribución de la información, el acceso gratuito a contenidos de calidad, las redes y las comunidades de aprendizaje para compartir y generar nuevas formas de aprender, el desarrollo tecnológico que se está produciendo en Internet (realidad aumentada, tecnología móvil, wearable…) y la capacidad de las redes… obligan a instituciones universitarias a replantear sus departamentos para responder con inteligencia a estos retos. Las plataformas MOOC no son ajenas a estos cambios, y en un futuro inmediato van a incorporar toda las experiencias y desarrollos en el área de las anotaciones multimedia colectivas, innovaciones que en estos momentos encuentran en estas plataformas masivas un escenario ideal de desarrollo, a la vez que una prueba y experimentación para la investigación educativa.

Sin duda, en estos nuevos entornos encontramos un espacio idóneo para el desarrollo de nuevas experimentaciones, estudios y desarrollos educativos como el que planteamos con el proyecto que presentamos. Donde hemos podido comprobar cómo en general, las anotaciones multimedia colectivas están más valoradas por los estudiantes cuando son más fáciles de utilizar (como se observa en las diferencias de medias), y reúnen ciertas funcionalidades específicas que representan las prácticas y tendencias encontradas en los jóvenes de hoy. Como serían aquellas relacionadas con la movilidad, las redes sociales, la interacción colectiva y la profusión de significados compartidos, como se observa en las funciones más valoradas y en las respuestas abiertas al comparar las dos herramientas. Son funciones añadidas a la nueva herramienta Open Video Annotation (OVA) que pretende estar también en sintonía con una competencia simbólica y comunicativa del estudiante universitario, más crítico y preparado para lo que Castell (2012: 2324) define como «autocomunicación de masas»; y que considera vital en la «construcción simbólica» al depender en gran medida «de los marcos creados.... es decir, la transformación del entorno de las comunicaciones afecta directamente a la forma en que se construye el significado».

Consideramos que son muchas las posibilidades formativas de las anotaciones multimedia colectivas para la enseñanza universitaria, y van más allá del propio formato existente y alcanza este «marco creado» que representan hoy los MOOC, siendo interesante su aplicación e investigación en contextos educativos diferentes a los estudiados en este trabajo, como podrían ser: a) Los modelos semipresenciales desarrollados actualmente en las universidades con materiales y recursos de apoyo a la docencia; b) Objetos de aprendizaje con anotaciones multimedia y web semántica (GarcíaBarriocanal, Sicilia, SánchezAlonso & Lytras, 2011); c) Supervisión en el practicum (Miller & Carney, 2009) con eportafolios (portafolios electrónicos) de evidencias multimedia donde de forma colectiva se compartan los significados otorgados en las anotaciones; d) Incluso para la difusión científica, como propone VázquezCano (2013: 90) combinando el formato escrito con el «videoartículo» y la «píldora científica»; hecho que le proporcionaría mayor difusión, visibilidad y flujo de intercambio a la producción científica. Contextos y experiencias todos ellas innovadoras, y acordes con las prácticas que deseamos que se produzcan de forma generalizada en las universidades, representando un liderazgo más decidido en la «sociedad del conocimiento».

Apoyos y notas

El proyecto de colaboración «Open Video Annotation Project» (20122014) (http://goo.gl/51W37d) fue posible gracias a la financiación conjunta de instituciones como: Becas Talentia Junta de Andalucía), Grupo GTEA (PAI: SEJ462) (http://gtea.uma.es) de la Junta de Andalucía y la Universidad de Málaga y The Center for Hellenic Studies (CHS) (Harvard University) (http://chs.harvard.edu) (09072014).

1 Estadística de YouTube (http://goo.gl/AlYrCL) (09072014).

2 Workshop internacional sobre anotaciones multimedia «iAnnote14», San Francisco. California (EEUU), April 36, 2014 (http://iannotate.org). (09072014).

3 Plataforma de software libre http://github.com.

4 El primer curso que utilizó OVA fue Poetry in America: Whitman en edX Harvard University (http://goo.gl/I9bupN) (09072014).

5 Herramienta OVA (http://openvideoannotation.org) (09072014).

Referencias

Aguaded, I. & Sánchez, J. (2008). Niños adolescentes tras el visor de la cámara: expe-riencias de alfabetización audiovisual. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 14, 293-308.

Aguaded, J. & Macías, Y. (2008). Televisión universitaria y servicio público. Co-municar, 31, XVI, 681-689. (http://doi.org/cd4fkw).

Angehrn, A., Luccini, A. & Maxwell, K. (2009). InnoTube: A Video-based Connection Tool Supporting Collaborative Innovation. Interactive Learning Environments, 17, 3, 205-220. (http://doi.org/bw48vv).

Area, M. (2005). Los criterios de calidad en el diseño y desarrollo de materiales didácticos para la www. Comunicación y Pedagogía, 204, 66-72.

Bangor, A., Kortum, P.T. & Miller, J.T. (2008). An Empirical Evaluation of the System Usability Scale. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24(6), 574-594.

Bangor, A., Kortum, P.T. & Miller, J.T. (2009). Determining What Individual SUS Scores Mean: Adding an Adjective Rating Scale. Journal of Usability Studies. 4 (3), 114-123.

Bargas, J.A., Lötscher, J., Orsini, S. & Opwis, K. (2009). Intranet Satisfaction Questionnaire: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Measure User Satisfaction with the Intranet. Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 1241-1250. (http://doi.org/b39md8).

Bartolomé, A. (1997). Uso interactivo del vídeo. In J. Ferrés & P. Marques (Coord.), Comunicación educativa y nuevas tecnologías. Barcelona: Praxis. 320 (1-13).

Bartolomé, A. (2003). Vídeo digital. Comunicar, 21, 39-47. (http://goo.gl/MDcYOt) (29-04-2014).

Bevan, N. (1997). Quality and Usability: A New Framework. In Van Veenendaal, E. & McMullan, J. (Eds.), Achieving Software Product Quality. Netherlands: Tutein Nolthenius, 25-34.

Blázquez, J.J., Chamizo, J., Cano, E. & Gutiérrez, S. (2013). Calidad de vida universitaria: Identificación de los principales indicadores de satisfacción estudiantil. Revista de Educación, 362, 458-484. (http://doi.org/tp5).

Cabero, J. (2004). El diseño de vídeos didácticos. In J. Salinas, J. Cabero & I. Aguaded (Coords.), Tecnologías para la educación: diseño, producción y evaluación de medios para la formación docente (PP. 141-156). Madrid: Alianza.

Castells, M. (2012). Redes de indignación y esperanza. Madrid: Alianza.

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M. & Bergman, M. (2014). Formative Assessment with eRubrics: an Approach to the State of the Art. Revista de Docencia Universitaria. 12, 1, 23-29. (http://goo.gl/A4cpaa).

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M. & Monedero, J.J. (2014). Evolución en el diseño y fun-cionalidad de las rúbricas: desde las rúbricas «cuadradas» a las erúbricas federadas. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 12, 1, 81-98. (http://goo.gl/xNhnqR).

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M. (1994). Los vídeos didácticos: claves para su producción y evaluación. Pixel Bit. Sevilla, 1, 31-42. (http://goo.gl/w3Ayi6).

Colasante, M. (2011). Using Video Annotation to Reflect on and Evaluate Physical Education Pre-service Teaching Practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(1), 66-88. (http://goo.gl/f2HfZB).

Díaz-Arias, R. (2009). El vídeo en el ciberespacio: usos y lenguaje. Comunicar, 33, 17, 63-71. (http://doi.org/ftt5qr).

Etscheidt, S. & Curran, C. (2012). Promoting Reflection in Teacher Preparation Pro-grams: A Multilevel Model. Teacher Education and Special Education 35(1) 7-26. (http://doi.org/dk53x2).

Ferrés, J. (1992). Vídeo y educación. Barcelona: Paidós.

García-Barriocanal, E., Sicilia, M.A., Sánchez-Alonso, S. & Lytras, M. (2009). Se-mantic Annotation of Video Fragments as Learning Objects: A Case Study with YouTube Videos and the Gene Ontology. Interactive Learning Environments, 19, 1, 25-44. (http://doi.org/b2pkpf).

García-Valcárcel, A. (2008). El hipervídeo y su potencialidad pedagógica. Revista Lati-noamericana de Tecnología Educativa (RELATEC), 7, 2, 69-79.

Giroux, H.A. (2001). Cultura, política y práctica educativa. Barcelona: Graó.

Guo, P., Kim, H. & Rubin, R. (2014). How Video Production Affects Student En-gagement: An Empirical Study of MOOC Videos. Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning @ scale conference (pp. 41-50. March 4-5, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. (http://doi.org/tp6).

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hosack, B. (2010). VideoANT: Extending Online Video Annotation Beyond Content Delivery. TechTrends, 54, 3, 45-49.

Ingram, J. (2014). Supporting Student Teachers in Developing and Applying Pro-fessional Knowledge with Videoed Events. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(1), 51-62. (http://doi.org/tp7).

Kirakowski, J. & Corbett, M. (1988). Measuring User Satisfaction. 4ª Conference of the British Computer Society Human-Computer Interaction Specialist Group, 329-338.

McNamara, N. & Kirakowski, J. (2011). Measuring User-satisfaction with Electronic Consumer Products: The Consumer Products Questionnaire. International Journal Human-Computer Studies. 69, 375-386. (http://doi.org/d5xzqn).

Miller, M. & Carney, J. (2009). Lost in Translation: Using Video Annotation Software to Examine How a Clinical Supervisor Interprets and Applies a State-mandated Teacher Assessment Instrument. The Teacher Educator, 44(4), 217-231, (http://doi.org/dhj2bv).

Molich, R., Ede, M.R., Kaasgaard, K. & Karyukin, B. (2004). Comparative Usability Evaluation. Behaviour & Information Technology, 23(1), 65-74.

Orland-Barak, L. & Rachamim, M. (2009). Simultaneous Reflections by Video in a Second-order Action Research-mentoring Model: Lessons for the Mentor and the Mentee. Reflective Practice, 10, 5, 601-613. (http://doi.org/db82mr).

Picci, P., Calvani, A. & Bonaiuti, G. (2012). The Use of Digital Video Annotation in Teacher Training: The Teachers’ Perspective. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 600-613. (http://doi.org/tp8).

Rich, P. & Trip, T. (2011). Ten Essential Questions Educators Should Ask When Using Video Annotation Tools. TechTrends, 55, 6, 16-24.

Rich, P. J., & Hannafin, M. (2009a). Scaffolded Video Self-analysis: Discrepancies between Preservice Teachers’ Perceived and Actual Instructional Decisions. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 21(2), 128-145.

Rich, P.J. & Hannafin, M. (2009b). Video Annotation Tools. Technologies to Scaffold, Structure, and Transform Teacher Reflection. Journal of Teacher Education, 60, 1, 52-67. (http://doi.org/dzdv4n).

Salinas, J. (2013). Audio y vídeo Podcast para el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras en la formación docente inicial. IV Jornadas Internacionales de Campus Virtuales. 14-15 Febrero. Universidad de las Islas Baleares. (http://goo.gl/EHq2Jo) (29-04-2014).

Sauro, J. (2011). Measuring Usability with the System Usability Scale (SUS) (http://goo.gl/63krpp) (29-04-2014).

Schön, D.A. (1998). El profesional reflexivo: ¿cómo piensan los profesionales cuando actúan? Barcelona: Paidós.

Vázquez-Cano, E. (2013). El videoartículo: nuevo formato de divulgación en revistas científicas y su integración en MOOC. Comunicar, 41, XXI, 83-91.(http://doi.org/tnk).

Yang, S., Zhang, J., Su, A. & Tsai, J. (2011). A collaborative multimedia annotation tool for enhancing knowledge sharing in CSCL. Interactive Learning Environments 19, 1, 45-62. (http://doi.org/cdtxd7).

Document information

Published on 31/12/14

Accepted on 31/12/14

Submitted on 31/12/14

Volume 23, Issue 1, 2015

DOI: 10.3916/C44-2015-06

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?