(→2.4. Multiple characteristic optimisation) |

|||

| Line 405: | Line 405: | ||

| colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 3'''. Fuzzy rules | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 3'''. Fuzzy rules | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION= | =3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION= | ||

Revision as of 13:20, 1 September 2021

Abstract

A hybrid multi-output approach which combined the Taguchi method and fuzzy logic was used in this research in order to optimise the mechanical and physical properties of PVC pipes. Eight techological parameters which mostly define the extrusion process were taken into consideration in order to obtain the best possible results for six measurable quality characteristics of PVC pipes. Eighteen experiments with the same number of different parameter value sets were conducted resulting in eighteen various PVC pipe samples. The sample from the second experiment showed the highest value of comprehensive output measure (COM = 0.615), while the lowest COM value (0.359) was noted with the sample no. 13. The results of ANOVA revealed that traction speed is the most significant parameter affecting multiple characteristics with contribution of 28.86%. The optimum combination of factors and their levels is , , , , , , , – the sample produced at traction speed of 8.8 m/min, nozzle temperature of 211℃, expander doser speed of 23.2 rpm, extruder screw speed of 17.5 rpm, coextruder screw speed of 40.6 rpm, barrel temperature of 178 ℃, extruder mixture doser speed of 28.1 rpm and the coextruder mixture doser speed of 36.4 rpm.

Keywords: PVC, extrusion, Taguchi method, fuzzy logic, multicriteria optimisation

1. Introduction

Drainage pipes made of plastic materials play a significant role in the construction of complex infrastructure pipeline systems. Today, they are almost the default option for draining different types of wastewater from the immediate human environment to a treatment plant or to a direct discharge in a suitable receiver.Easy installation, relatively low price, good hydraulic properties, long period of exploitation, the possibility of complete recycling, as well as other specific properties give them a huge advantage over pipes made of classic materials.

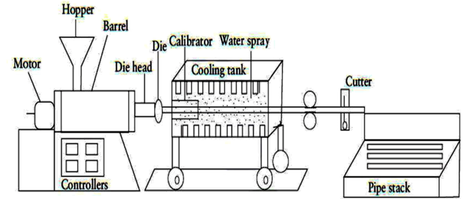

According to estimates, about 60% of the total world production of plastic pipes refers to PVC pipes [1], among which the dominant role is dedicated to pipes made of hard or unplasticized polyvinyl chloride (uPVC) and thermoplastic polyethylene (PE). Their production is based on the technological process of extrusion (Figure 1) [2].

|

| Figure 1. PVC pipe extrusion (Source: [2]) |

The quality of mechanical and physical properties of the extruded PVC pipes is measured through several characteristics out of which the following six were chosen as the most important from this papers’ point of view: ring stiffness, ring flexibility, TIR (true impact rate) test, wall thickness, longitudinal shrinking and the thickness of the outer and inner layers.

Achieving the desired quality level of the listed characteristics is of great importance for the functional behavior of the product. Optimal parameter tuning is considered to be the most significant factor for improvement of extruded products’ quality [3]. Therefore, a hybrid multi-output quality optimisation approach, based on the combination of fuzzy logic and Taguchi method was applied in this paper in order to determine the optimal values of eight extrusion parameters ie. factors included in the production of PVC pipes: (1) traction speed, (2) nozzle temperature, (3) expander doser, (4) extruder screw speed, (5) coextruder screw speed, (6) barrel temperature, (7) extruder mixture doser, (8) coextruder mixture doser.

Taguchi’s method optimises the quality characteristics of a product “through the settings of process parameters and reduces the sensitivity of the system performance to sources of variation” [4]. Many researchers studied the effects of optimal machining parameters selection with aid of the Taguchi method. Diaz et al. [5] applied the Taguchi's method of robust design to “obtain the most appropriate values of a set of control factors in several design situations“. Ćurić et al. [6] compared two methodologies for identification of process parameters that affect geometric deviations in plastic injection molding for production of housing. Wang et al. [7] investigated the mechanism of micro injection molding parameters on cavity pressure and temperature. Sandip et al. [8]used Taguchi techniques to “study the defects in the plastic pipe and to optimise its manufacturing process”. Narasimha and Rejikumar [9] presented a systematic approach to establishing the root causes for the occurrence of defects and wastes in plastic extrusion process. Pawar et al. [10], Kumar et al. [11] and Kerealme et al. [12] used the Taguchi method to optimise PVC pipes’ wall thickness by tuning four ie. eight extrusion process parameters.Ariani et al. [13] tuned five parameters, while Verma and Dubey [14] and Sharma et al. [15] tuned three parameters in order to optimise one quality characteristic of PVC pipes.

Various authors tuned various extrusion process parameters but none of them tuned them to simultaneously improve multiple output quality characteristics of PVC pipes. However, adaptations of process parameters and multi-output optimisations through the implementation of fuzzy based Taguchi methods are not a novelty in other areas of creativity. Gupta et al. [4]applied the Taguchi method “with logical fuzzy reasoning for multiple output optimisation of high speed CNC turning of AISI P-20 tool steel using TiN coated tungsten carbide coatings”. Five machining parameters were tuned in their research to optimise four responses ie. output quality characteristics. Abd et al. [16] coupled Taguchi method with fuzzy logic to deal with “multi-objective optimisation problems for dynamic scheduling in robotic flexible assembly cells (RFACs)”. “The application of the Taguchi method with fuzzy logic for optimising the electrical discharge machining process with multiple performance characteristics” has been reported by Lin et al. [17], while Tarng et al. [18] used “fuzzy logic in the Taguchi method to optimise the submerged arc welding process with multiple performance characteristics”. The authors of those papers optimised six and five machining parameters respectively with considerations of two output quality characteristics. Although multi-output optimisations are a well known issue in the literature, proposed paper presents the first research where eight process parameters were tuned in order to optimise six output quality characteristics.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Design of experiment by Taguchi method

For the design of the experiment by Taguchi method, the number of parameters (factors) and their levels needed to be established at first. The experiment was based on eight most important process parameters which affect the quality of PVC pipes. They are designated with letters A to H and shown in Table 1 (A – traction speed, B – nozzle temperature, C – expander doser, D – extruder screw speed, E – coextruder screw speed, F – barrel temperature, G – extruder mixture doser and H – coextruder mixture doser).

| Symbol | Extrusion process parameters | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Traction speed (m/min) | 8.8 | 9.1 | - |

| B | Nozzle temperature (°C) | 201 | 206 | 211 |

| C | Expander doser (rpm) | 19.2 | 21.2 | 23.2 |

| D | Extruder screw speed (rpm) | 16.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 |

| E | Coextruder screw speed (rpm) | 39.6 | 40.6 | 41.6 |

| F | Barrel temperature (°C) | 174 | 176 | 178 |

| G | Extruder mixture doser (rpm) | 24.1 | 26.1 | 28.1 |

| H | Coextruder mixture doser (rpm) | 34.4 | 36.4 | 38.4 |

Chosing an appropriate orthogonal array is crucial for the success of designed experiment [19]. It depends on the number of process parameters and their levels. In this experiment, one parameter had two levels (21) and seven parameters had three levels (37). Thus, the orthogonal array of 18 experimental runs was applied () resulting in the same number of various PVC pipe samples (Table 2).

| Ex. No. |

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.8 | 201 | 19.2 | 16.5 | 39.6 | 174 | 24.1 | 34.4 |

| 2 | 8.8 | 201 | 21.2 | 17.5 | 40.6 | 176 | 26.1 | 36.4 |

| 3 | 8.8 | 201 | 23.2 | 18.5 | 41.6 | 178 | 28.1 | 38.4 |

| 4 | 8.8 | 206 | 19.2 | 16.5 | 40.6 | 176 | 28.1 | 38.4 |

| 5 | 8.8 | 206 | 21.2 | 17.5 | 41.6 | 178 | 24.1 | 34.4 |

| 6 | 8.8 | 206 | 23.2 | 18.5 | 39.6 | 174 | 26.1 | 36.4 |

| 7 | 8.8 | 211 | 19.2 | 17.5 | 39.6 | 178 | 26.1 | 38.4 |

| 8 | 8.8 | 211 | 21.2 | 18.5 | 40.6 | 174 | 28.1 | 34.4 |

| 9 | 8.8 | 211 | 23.2 | 16.5 | 41.6 | 176 | 24.1 | 36.4 |

| 10 | 9.1 | 201 | 19.2 | 18.5 | 41.6 | 176 | 26.1 | 34.4 |

| 11 | 9.1 | 201 | 21.2 | 16.5 | 39.6 | 178 | 28.1 | 36.4 |

| 12 | 9.1 | 201 | 23.2 | 17.5 | 40.6 | 174 | 24.1 | 38.4 |

| 13 | 9.1 | 206 | 19.2 | 17.5 | 41.6 | 174 | 28.1 | 36.4 |

| 14 | 9.1 | 206 | 21.2 | 18.5 | 39.6 | 176 | 24.1 | 38.4 |

| 15 | 9.1 | 206 | 23.2 | 16.5 | 40.6 | 178 | 26.1 | 34.4 |

| 16 | 9.1 | 211 | 19.2 | 18.5 | 40.6 | 178 | 24.1 | 36.4 |

| 17 | 9.1 | 211 | 21.2 | 16.5 | 41.6 | 174 | 26.1 | 38.4 |

| 18 | 9.1 | 211 | 23.2 | 17.5 | 39.1 | 176 | 28.1 | 34.4 |

2.2. Sample quality characteristics measuring

Testing the physical and mechanical characteristics of the produced samples (three-layer unplasticized PVC pipes with outside diameter of 110 mm) was carried out 24 hours after the production process. It should be noted that samples were manufactured according to standard EN 13476-1:2018 [20] in the Company for Polymer Processing “Peštan”, Serbia. Theysohn Twin-Screw Extruder was used for the extrusion process.

Pipe ring stifness (expressed in kN/m2) and flexibility (expressed in N) were tested with Shimadzu AGS-X 20 kN dynamometer. Treshold values for these parameters are defined by standards SRPS EN ISO 9969:2016 [21] and SRPS EN ISO 13968:2009 [22], respectively.

Shock test apparatus IMPACT 2000, designed on Faculty of Technical Sciences, Čačak, Serbia was used for testing the pipe’s resistance to external blows (TIR test). Treshold values for this test are expressed in % and are defined by standard SRPS EN 744:2008 [23].

Wall thickness (in mm) was measured with a digital vernier caliper with accuracy of 0.01 mm. Reference values are defined in SRPS EN ISO 3126:2009 [24].

Longitudinal shrinking (expressed in %) was measured in Binder furnace dryers. The temperature inside the furnace was monitored by thermocouples, while the temperature of the tube was measured using a non-contact IR thermometer HT6889. Obtained measures were compared with the ones defined in SRPS EN ISO 2505:2013 [25].

The thickness of the outer and inner smooth layers were measured using a millimeter image distribution with Atorn 8x, whereas the treshold values are expressed in mm and defined in SRPS EN 13476-2:2009 [26].

2.3. Signal-to-noise ratios and single characteristic optimisation

Results of quality characteristics measurments for eighteen samples were transformed to signal-to-noise ratios (S/N) in order to obtain the best comination of factors (parameters) for each characteristic.

The S/N ratios were calculated by the logarithmic transformation of loss function [19]

|

|

(1) |

|

|

(2) |

|

|

(3) |

where to , = observed response value at each experiment, = number of observations in each experiment and = variance.

Pipe ring stiffness and flexibility are desirable to have the highest possible values. Thus, the higher the better function was used for calculation of their S/N ratios (Eq. (1)). For the TIR test and longitudinal shrinkage, the lowest possible values are desired so the lower the better function was selected for calculation of their S/N ratios (Eq. (2)). S/N ratios for the wall thickness and the thickness of the outer and inner layers are obtained by Eq. (3) since those two characteristics require nominal measures (nominal is the best function).

Finally, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for the evaluation of the most influential factor for each quality characteristic of unplasticized PVC pipes.

2.4. Multiple characteristic optimisation

Since the Taguchi method is “designed to handle the optimisation of a single performance characteristic” [4], fuzzy logic was used to identify the optimal combination of process parameters that should simultaneously improve all the quality characteristics of PVC pipes. Implementation of fuzzy logic was intended to result in one value ie. response called comprehensive output measure (COM), for all the six considered quality characteristics.

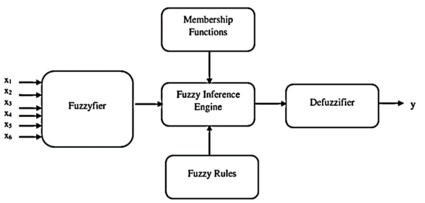

A fuzzy system ie. fuzzy logic unit (FLU) is composed of a fuzzifier, membership functions, a fuzzy

rule base, an inference engine and a defuzzifier. The structure of the six-input-one-output fuzzy logic computing architecture used in this research is shown in Figure 2.

|

|

| Figure 2. Structure of the six-input-one-output fuzzy logic unit |

Input variables for the fuzzy inference rules in the present study were the S/N ratios for six quality characteristics of PVC pipes (). The output variable () represents the COM which is derived by a defuzzification method. The larger is the COM, the better are the performance characteristics. In this study, the center of gravity method is applied to transform the fuzzy inference output into a non-fuzzy value

|

|

(4) |

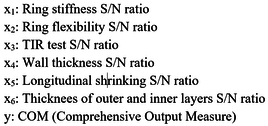

The fuzzy rule base with sixty four fuzzy if–then rules is graphically presented in Figure 3.

|

|

|

| Figure 3. Fuzzy rules |

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Optimisation of individual characteristics

The results of testing the mechanical and physical properties of the produced pipe samples are shown in Table 3. It has been noticed that there was a significant influence of varying the level of parameters on the given quality characteristics.

| Sample | Ring stiffness

[kN/m2] |

Ring flexibility

[N] |

TIR test

[%] |

Wall

thickness [mm] |

Longitudinal shrinking

[%] |

Thickness of the outer and inner layers

[mm] |

| 1 | 4.40 | 969.70 | 7.90 | 3.10 | 7.47 | 0.59 |

| 2 | 7.40 | 969.70 | 7.90 | 3.58 | 5.77 | 0.71 |

| 3 | 6.50 | 1153.90 | 15.60 | 3.50 | 5.47 | 0.80 |

| 4 | 6.00 | 1258.40 | 7.30 | 3.28 | 6.57 | 0.78 |

| 5 | 5.60 | 1224.50 | 30.60 | 3.25 | 5.67 | 0.77 |

| 6 | 6.50 | 1172.80 | 7.70 | 3.63 | 6.57 | 0.81 |

| 7 | 4.60 | 1005.60 | 1.00 | 3.25 | 5.47 | 0.73 |

| 8 | 6.80 | 1166.80 | 13.40 | 3.48 | 6.87 | 0.82 |

| 9 | 5.90 | 1142.90 | 5.60 | 3.35 | 4.57 | 0.82 |

| 10 | 4.20 | 862.50 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 7.97 | 0.65 |

| 11 | 5.10 | 982.80 | 1.50 | 3.25 | 5.17 | 0.82 |

| 12 | 5.60 | 1028.60 | 9.20 | 3.25 | 6.17 | 0.74 |

| 13 | 4.50 | 1032.50 | 3.40 | 3.15 | 7.77 | 0.56 |

| 14 | 4.70 | 1061.40 | 8.40 | 3.30 | 7.17 | 0.63 |

| 15 | 5.00 | 1142.00 | 8.40 | 3.35 | 6.37 | 0.62 |

| 16 | 4.70 | 975.80 | 7.90 | 3.10 | 6.47 | 0.78 |

| 17 | 5.10 | 1136.00 | 14.20 | 3.20 | 6.17 | 0.73 |

| 18 | 7.20 | 1240.50 | 7.90 | 3.55 | 5.77 | 0.71 |

Calculated values of signal-to-noise ratios are given in Table 4.

| Sample | Ring stiffness | Ring flexibility | TIR test | Wall thickness | Longitudinal shrinking | Thickness of the outer and inner layers |

| 1 | 12.869 | 59.733 | -17.952 | -0.819 | -17.466 | -0.114 |

| 2 | 17.384 | 59.733 | -17.952 | -0.241 | -15.223 | 3.487 |

| 3 | 16.258 | 61.243 | -23.862 | -1.072 | -14.760 | -1.840 |

| 4 | 15.563 | 61.994 | -17.266 | -1.886 | -16.351 | -0.894 |

| 5 | 14.964 | 61.759 | -29.714 | -0.535 | -15.072 | -2.509 |

| 6 | 16.259 | 61.384 | -17.729 | -0.972 | -16.351 | -0.895 |

| 7 | 13.256 | 60.048 | -1.5836 | -0.106 | -14.759 | -1.656 |

| 8 | 16.650 | 61.340 | -22.542 | -0.522 | -16.739 | -0.893 |

| 9 | 15.417 | 61.160 | -14.963 | -0.610 | -13.198 | 1.538 |

| 10 | 12.465 | 58.715 | -3.5218 | -0.745 | -18.029 | 0.549 |

| 11 | 14.151 | 59.849 | -3.5218 | -0.535 | -14.269 | -0.892 |

| 12 | 14.964 | 60.250 | -19.276 | -1.305 | -15.806 | -2.508 |

| 13 | 13.064 | 60.278 | -10.630 | -2.033 | -17.808 | -1.412 |

| 14 | 13.442 | 60.518 | -18.486 | -1.708 | -17.110 | -2.425 |

| 15 | 13.979 | 61.153 | -18.486 | -2.092 | -16.083 | -2.425 |

| 16 | 13.442 | 59.787 | -17.953 | -0.010 | -16.218 | 0.465 |

| 17 | 14.151 | 61.108 | -23.046 | -0.106 | -15.806 | -1.656 |

| 18 | 17.147 | 61.872 | -17.952 | -0.747 | -15.223 | -1.659 |

Calculated values of S/N ratios served as input values for the ANOVA analysis as well as for determination of the best combinations of factors for each quality characteristic. Table 5 shows the results of ANOVA analysis for ring flexibility S/N ratios.

| Variable (Factor) | Average level | Degree of freedom | Sum of squares | Mean of squares | F-ratio | Contribution (%) | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| A | 60.93 | 60.39 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.319 | 1.319 | 2.67 | 9.34 |

| B | 59.92 | 61.18 | 60.89 | 2 | 5.226 | 2.612 | 5.29 | 37.02 |

| C | 60.09 | 60.72 | 61.18 | 2 | 3.549 | 1.774 | 3.59 | 25.14 |

| D | 60.83 | 60.66 | 60.50 | 2 | 0.337 | 0.169 | 0.34 | 2.39 |

| E | 60.57 | 60.71 | 60.71 | 2 | 0.008 | 0.040 | 0.08 | 0.57 |

| F | 60.68 | 60.67 | 60.64 | 2 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| G | 60.53 | 60.36 | 61.10 | 2 | 1.790 | 0.895 | 1.81 | 12.68 |

| H | 60.76 | 60.37 | 60.86 | 2 | 0.822 | 0.411 | 0.83 | 5.83 |

| Error | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | 7 |

| Total | - | - | - | 17 | - | - | - | 100 |

ANOVA results revealed that nozzle temperature (factor B) has the greatest contribution to the pipe ring flexibility (37.02%). The best combination of factors and their levels which affect the ring flexibility is A1, B2, C3, D1, E2, F1, G3, H3.

The same analysis procedure was applied to optimise the other five quality characteristics of PVC pipes. Table 6 shows the best combinations of factors and their levels which affect the appropriate qulity characteristics. The most influential factors are also determined for each quality characteristic.

| Quality characteristics | Combination of factors | The most infulential factor |

| Ring stiffness | A1, B3, C3, D2, E2, F2, G3, H2 | C – 39.82% |

| Ring flexibility | A1, B2, C3, D1, E2, F1, G3, H3 | B – 37.02% |

| TIR test | A2, B1, C1, D1, E1, F2, G2, H2 | C – 24.32% |

| Wall thickness | A1, B3, C3, D2, E1, F3, G2, H2 | B – 57.26% |

| Longitudinal shrinking | A1, B3, C3, D1, E3, F3, G1, H2 | C – 27.02% |

| Thickness of the outer and inner layers | A1, B1, C1, D1, E2, F2, G2, H2 | H – 36.48% |

The doser expander has the largest influence on three analyzed characteristics: ring stiffness, TIR test and longitudinal shrinking, with contributions of 39,82%, 24,32% and 27,02%, respectively. Nozzle temperature has the largest influence on ring flexibility (37,02%) and wall thickness (57,26%), while the thickness of the outer and inner layers is mostly influenced by coextruder mixture doser with contribution of 36.48%.

3.2. Optimisation of multiple characteristics

Previous table makes it clear that the parameter set that optimises one quality characteristics does not match a parameter set that optimises another one. Thus, the defined fuzzy logic unit (figure 2) was applied and single responses for six charactersitics were obtained for 18 pipe samples in the form of comprehensive output measures (Table 7). The sample from the second experiment showed the highest COM value (0.615), while the lowest COM value (0.359) was noted with the sample no. 13.

| Sample | COM |

| 1 | 0.432 |

| 2 | 0.615 |

| 3 | 0.521 |

| 4 | 0.468 |

| 5 | 0.518 |

| 6 | 0.504 |

| 7 | 0.519 |

| 8 | 0.512 |

| 9 | 0.583 |

| 10 | 0.376 |

| 11 | 0.530 |

| 12 | 0.445 |

| 13 | 0.359 |

| 14 | 0.373 |

| 15 | 0.440 |

| 16 | 0.484 |

| 17 | 0.470 |

| 18 | 0.540 |

The results of ANOVA for comprehensive output measures are shown in Table 8. Traction speed (factor A) is the most significant parameter which affects multiple characteristics with contribution of 28.86%. Nozzle temperature (factor B) and expander doser (factor C) also have a large influence on multiple characteristics (20.74% and 20.01%). Factors with insignificant influence on multiple quality characteristics [27] are coextruder screw speed (factor E – 2.48%) and extruder mixture doser (factor G – 1.06%).

| Variable (Factor) | COM level averages | Degree of freedom | Sum of squares | Mean of squares | F-ratio | Contribution (%) | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| A | 0.519 | 0.446 | 0.00 | 1 | 8.291 | 8.291 | 10.60 | 28.86 |

| B | 0.486 | 0.444 | 0.518 | 2 | 5.960 | 2.980 | 3.81 | 20.74 |

| C | 0.440 | 0.503 | 0.506 | 2 | 5.749 | 2.875 | 3.67 | 20.01 |

| D | 0.487 | 0.499 | 0.462 | 2 | 1.383 | 0.692 | 0.88 | 4.81 |

| E | 0.483 | 0.494 | 0.471 | 2 | 0.712 | 0.356 | 0.46 | 2.48 |

| F | 0.497 | 0.492 | 0.502 | 2 | 2.625 | 1.313 | 1.68 | 9.14 |

| G | 0.484 | 0.494 | 0.514 | 2 | 0.304 | 0.152 | 0.19 | 1.06 |

| H | 0.470 | 0.538 | 0.484 | 2 | 2.138 | 1.069 | 1.37 | 7.44 |

| Error | - | - | - | 2 | 1.565 | 0.783 | - | 5.45 |

| Total | - | - | - | 17 | - | - | - | 100 |

The optimum combination of factors and their levels which affect all the measured quality characteristics is A1, B3, C3, D2, E2, F3, G3, H2.

Optimum combination of factors was used to produce three more control samples (designated with O) whose output quality characteristics were then measured, averaged and compared with the measures from the experiment with highest COM value – sample 2 (A1, B1, C2, D2, E2, F2, G2, H2). The comparison of these measurements is shown in table 9.

| Sample | Ring stiffness

(kN/m2) |

Ring flexibility

(N) |

TIR test (%) | Wall thickness

(mm) |

Longitudinal shrinking

(%) |

Thicknees of outer and inner layers (mm) | COM |

| Sample 2 | 7.40 | 969.70 | 7.90 | 3.58 | 5.77 | 0.71 | 0.615 |

| Sample O | 7.09 | 1385.89 | 0 | 3.67 | 6.37 | 0.80 | 0.813 |

| Improvement | -4% | +43% | +100% | +2.50% | -10% | +13% | +32% |

Results of comparison show that ring flexibility, wall thickness and thickness of outer and inner layers were significantly improved (43%, 2.5% and 13%, respectively). TIR test was reduced by 100%. Ring stiffness and longitudinal shrinking showed slightly worse results (-4% and -10%).

Finally, COM value for sample O has been improved by 0.198 (32%) compared to sample 2. COM values was calculated by the following equation:

|

|

(5) |

where ηm is the total mean of the comprehensive output measure (COM) for all experimental runs, is the mean of comprehensive output measure at the optimum level of control factors and q is the number of the process parameters that significantly affect the multiple performance characteristics.

4. CONCLUSION

The main focus of this study was to propose a solution to the problem of optimisation of the extrusion process. Defined methodology can help the polymer processing industry to obtain a solution that is not only economical because of the small number of experiments required but also ensures a high level of product quality.

Based on the presented results, conclusions can be drawn in several directions:

- Generally, proposed hybrid multi-output approach which combines the Taguchi method and fuzzy logic can succesfully be used in order to optimise the quality characteristics of PVC pipes.

- Significant influence of process parameters tuning on the quality of the product, expressed through the measures of six mechanical and physical properties was noted.

- Taguchi method, in a well established manner, can succesfully be used for optimisation of one output in form of individual quality characteristics.

- The best combinations of factors and their levels which affect different characteristics are: A1, B3, C3, D2, E2, F2, G3, H2 for ring stifness; A1, B2, C3, D1, E2, F1, G3, H3 for ring flexibility; A2, B1, C1, D1, E1, F2, G2, H2 for TIR test; A1, B3, C3, D2, E1, F3, G2, H2 for wall thickness; A1, B3, C3, D1, E3, F3, G1, H2 for longitudinal shrinking; A1, B1, C1, D1, E2, F2, G2, H2 for the thickness of the outer and inner layers.

- ANOVA revealed which factor influences which characteristic the most. The doser expander has the largest influence on three analyzed characteristics: ring stiffness, TIR test and longitudinal shrinking, with contributions of 39.82%, 24.32% and 27.02%, respectively. Nozzle temperature has the largest influence on ring flexibility (37.02%) and wall thickness (57.26%), while the thickness of the outer and inner layers is mostly influenced by coextruder mixture doser with contribution of 36.48%.

- Fuzzy logic was employed upon the data already processed by the Taguchi metod in order to simultaneously optimise multiple quality characteristics.

- The sample from the second experiment (A1, B1, C2, D2, E2, F2, G2, H2) showed the highest COM value (0.615), while the lowest COM value (0.359) was noted with the sample no. 13.

- The results of ANOVA revealed that traction speed (factor A) is the most significant parameter which affects multiple characteristics with contribution of 28.86%. Nozzle temperature (factor B) and expander doser (factor C) also have a large influence on multiple characteristics (20.74% and 20.01%). Factors with insignificant influence on multiple quality characteristics are coextruder screw speed (factor E – 2.48%) and extruder mixture doser (factor G – 1.06%).

- The optimum combination of factors and their levels which affect all the measured quality characteristics is A1, B3, C3, D2, E2, F3, G3, H2 – the sample produced at traction speed of 8.8 m/min, nozzle temperature of 211℃, expander doser speed of 23.2 rpm, extruder screw speed of 17.5 rpm, coextruder screw speed of 40.6 rpm, barrel temperature of 178 ℃, extruder mixture doser speed of 28.1 rpm and the coextruder mixture doser speed of 36.4 rpm

- Results of comparison of the optimum sample with the sample from the experiment with highest COM value showed that ring flexibility, wall thickness and thickness of outer and inner layers and TIR test were significantly improved (43%, 2.5%, 13%, 100% respectively). Ring stiffness and longitudinal shrinking showed slightly worse results (-4% and -10%). Finally, COM value for sample O has been improved by 0.198 (32%) compared to sample 2.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia, and these results are parts of the Grant No. 451-03-68/2020-14/200132 with University of Kragujevac – Faculty of Technical Sciences Čačak.

The authors would like to express their deepest gratitude to the Company for Polymer Processing “Peštan”, Serbia, for technical and logistical support in this study.

REFERENCES

- [1] PVC Pipes Market – Global Industry Trends, Share, Size, Growth, Opportunity and Forecast 2017-2022, available at: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/pvc-pipes-market---global-industry-trends-share-size-growth-opportunity-and-forecast-2017-2022-300420579.html, Accessed in February 2020

- [2] Muralisrinivasan, N. Update on troubleshooting the PVC extrusion process. iSmithers, 2011.

- [3] Raju, G., Sharma, M., Meena, L. Recent methods for optimisation of plastic extrusion process: A Literature Review. International Journal of Advanced Mechanical Engineering, 4(6): 583-588, 2014.

- [4] Gupta, A., Singh, H., Aggarwal, A. Taguchi-fuzzy multi output optimisation (MOO) in high speed CNC turning of AISI P-20 tool steel. Expert Systems with Applications, 38: 6822–6828, 2011.

- [5] Díaz, J., Hernandez, S., Romera, L., Fontan, A. Diseño y análisis térmico bajo incertidumbre en estructuras aeronáuticas. Revista internacional de métodos numéricos para cálculo y diseño en ingeniería, 27(2): 95-104, 2011.

- [6] Ćurić, D., Veljković, Z., Duhovnik, J. Comparison of methodologies for identification of process parameters affecting geometric deviations in plastic injection molding of housing using Taguchi method. Mechanika, 18(6): 671-676, 2012.

- [7] Wang, Q., Yang, C., Kaihui, D., Zhenghuan, W. Effect of Micro Injection Molding Parameters on Cavity Pressure and Temperature Assisted by Taguchi Method. Mechanika, 25(4): 261-268, 2019.

- [8] Gadekar, S., Khan, J., Dalu, R. Analysis of process parameters for optimisation of plastic extrusion in pipe manufacturing. International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications, 5(5): 71-74, 2015.

- [9] Narasimha, M., Rejikumar, R. Plastic pipe defects minimization. International Journal of Innovative Research & Development, 2:1337-1351, 2013.

- [10] Pawar, K., Jadhav, S., Dumbre, A., Sunny, A.V., Girish, H.S., Yadav, A. Experimental investigation to optimize the extrusion process for PVC pipe: A Case of Industry. International Journal of Advance Research and Innovative Ideas In Education, 3(2), 2017.

- [11] Kumar, D., Goyal, S., Joshi, R. Optimization of process parameters in extrusion of PVC pipes, using Taguchi method. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 8(1): 70-72, 2019.

- [12] Kerealme, S., Srirangarajalu, N., Asmare, A. Parameter Optimisation of Extrusion Machine Producing uPVC Pipes using Taguchi Method: A Case of Amhara Pipe Factory, International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 5(1): 65-75, 2016.

- [13] Ariani, F., Siregar, K., Syahputri, K., Rizkya, I. Improving quality of PVC pipes using Taguchi method. E3S Web of Conferences 125, 22004 ICENIS 2019.

- [14] Verma, K. M. Dubey, M. Optimisation of process parameters of plastic extrusion in pipe manufacturing. International Journal of Engineering and Management Research, 5(6): 276-280, 2015.

- [15] Sharma, G. V. S. S., Rao, R. U., Rao, P. S. A Taguchi approach on optimal process control parameters for HDPE pipe extrusion proces. Journal of Industrial Engineering International, 13: 215-228, 2017.

- [16] Abd, K., Abhary, K., Marian, R. Multi-objective optimisation of dynamic scheduling in robotic flexible assembly cells via fuzzy-based Taguchi approach. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 99: 250-259, 2016.

- [17] Lin, J.L. Wang, K.S. Yan, B.H. Tarng, Y.S. Optimisation of the electrical discharge machining process based on the Taguchi method with fuzzy logics. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 102(1-3), 48-55, 2000.

- [18] Tarng, Y.S., Yang, W.H. Juang, S.C. The Use of Fuzzy Logic in the Taguchi Method for the Optimisation of the Submerged Arc Welding Process. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 16: 688-694, 2000.

- [19] Ross, P. Taguchi Techniques for Quality Engineering. Tata McGraw Hill Publishing Co Ltd, 2005.

- [20] EN 13476-1:2018 – BSI Standards Publication – Plastics piping systems for non-pressure underground drainage and sewerage – Structured wall piping systems of unplasticized polyvinyl chloride (PVC-U), polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE).

- [21] SRPS EN ISO 9969:2016 – Thermoplastics pipes – Determination of ring stiffness

- [22] SRPS EN ISO 13968:2009 – Plastics piping and ducting systems — Thermoplastics pipes — Determination of ring flexibility

- [23] SRPS EN 744:2008 – Plastics piping and ducting systems - Thermoplastics pipes - Test method for resistance to external blows by the round-the-clock method

- [24] SRPS EN ISO 3126:2009 – Plastics piping systems — Plastics components — Determination of dimensions

- [25] SRPS EN ISO 2505:2013 – Thermoplastics pipes — Longitudinal reversion — Test method and parameters

- [26] SRPS EN 13476-2:2009 – Plastics piping systems for non-pressure underground drainage and sewerage - Structured-wall piping systems of unplasticized poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC-U), polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE) - Part 2: Specifications for pipes and fittings with smooth internal and external surface and the system, Type A

- [27] Kamaruddin, S., Khan, Z., Wan, K. S. The Use of the Taguchi Method in Determining the Optimum Plastic Injection Moulding Parameters for the Production of a Consumer Product. Jurnal Mekanikal, 18: 98-110, 2004.

Document information

Published on 07/09/21

Accepted on 31/08/21

Submitted on 02/09/20

Volume 37, Issue 3, 2021

DOI: 10.23967/j.rimni.2021.09.001

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?