(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== The t...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 142058344 to Velandia-Mesa et al 2017a) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 13:28, 27 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The training in research is fundamental in the quality of higher education and within this context, the technological mediation becomes pivotal to reach the student-centered learning objectives in any moment and at any time. The findings of a study, whose purpose has been to evaluate the results of the formative research of two groups of students that have interacted in learning environments (E-learning y U-learning), are presented. The research follows a quasi-experimental study with a design of chronological series and multiple treatment, framed in three stages that were defined as referencing, systematization, and analysis. The sample has been constituted by 189 students of 4th year degree in Childhood Education, at Universidad El Bosque in Bogotá, Colombia. The results reveal that U-learning environments strengthen and consolidate the formative research as a permanent process to learn educational research through the personalization, adaptation, and the situational learning, marking meaningful differences with respect to E-learning environments during the systematization stage. The intervention with U-learning environments has brought challenges and needs in the academic curriculum such as strengthening the link between evaluation and educational research in the field of professional practice, as well as the inclusion of technology to the end of making it something natural, adaptable, and interoperable, in a way that students would use it without even thinking about it.

1. Introduction

Quality in education is a key issue that has been included in the agendas of the Ibero-American governments in the last decade. The Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN, 2015-2016) points out that quality education is a generator of opportunities that change realities. In this context, quality in higher education is related to the capacity of university institutions to make it possible for students to achieve academic results directly related with their learning process and their area of study, through technology, professional practice, and research (Ardila, 2011).

Higher education should be essentially an ongoing process of research mediated by the development of science and technology, since these elements are fundamental for consolidating high quality education (Restrepo, 2003). This process requires an ongoing dialogue between the appropriation of knowledge, its transformation, and its linkage to the professional practice in order to ensure that students adapt to the conditions and requirements of the context, understanding that the quality of education is associated with the research practices and, at the same time, these are linked to the search for, construction, and appropriation of knowledge (Herrera, 2013).

It is in this context that formative research, which is conceived as the research process that is developed so that the student is educated from problematic situations close to the curricular context and their professional future, becomes meaningful (Restrepo, 2003). The academic scenario of our work and that of the participants fourth-year students on the Early Childhood Education degree at El Bosque University, in Bogotá, Colombia-, necessarily leads us to contemplate formative research for academic training in Educational research from the perspective of the experiences and paradigmatic and methodological approaches that logic and their particular activities impose in the field of education.

Strengthening the link between educational research and professional practice is one of the fundamental objectives of the Higher Education Institutions and, therefore, it is an element of essential importance for the generation of new knowledge. From this perspective, the student is expected to follow the path of educational research through continuous and systematic praxis, and in so doing, to fulfill student-centered learning objectives. Academic training for research should take advantage of all those activities that are oriented towards the «learning to learn» process with the purpose of strengthening and consolidating skills and knowledge in students that enable them to successfully develop activities related to academic research, development, and innovation.

In Colombia, for 65.000 students which represents 5% of the entire child population according to the National Accreditation Council (CNA, 2015), virtual assistance has been essential in their formative process. In the context of the study presented in this article, technological tools have been used to assist and evaluate the formative processes in educational research, particularly through applications which capture and edit digital data, software for the analysis and systematization of information, electronic resources for bibliometric studies, and platforms for evaluation and research evaluation. Recent technological developments have also allowed access to databases and referencing managers for formative processes in research, which has facilitated the use of specialized sources of information (Velandia, 2014). Similarly, technological progress has strengthened research in the way that it has initiated collaborative work and communication between peer researchers in accessing research practices, socializations and disclosures (Herrera, 2013). Another fundamental factor that is associated with technological development in formative research processes has been the orientation and flexibilization of tutoring in synchronous and asynchronous manners, which in terms of quality of education is considered to play a pivotal role in the development of research competence through the formative assessment of the student. (Martínez, Pérez, & Martínez, 2016).

Nevertheless, for the participants in this study, who are being trained as future teachers in Early Childhood Education, there are conditions and elements where virtual environments do not facilitate a permanent dialogue between educational research and the reality of the student in his/her professional practice. Only 54.3% of the students carry out their professional practice in urban and rural areas (Velandia, 2014), where internet connection becomes a factor that makes the systematization of the pedagogical experience and the tracking process of formative research difficult. Although digital resources have allowed the extension of guidance processes in other scenarios beyond the classroom, certain requirements such as access to electronic devices and the quality of the internet connection are still to be met, under the assumption of effective functioning of the tools at any time and location. Strengthening the link between technology and formative research in the field of professional teaching practice implies restructuring the educational experience to consider acknowledged standards for the academic community and, at the same time, it must respect the rigor of the systematization. This task requires an intellectual labour, the manifestation of skills, and the implementation of those resources that assist the process. Educational research must systematize the experience in which analysis is key to build knowledge and to developing professional competences. With this statement in mind and with the contextual need to build environments that allow the monitoring of the processes of formative research at any time and place, an ad hoc U-learning environment was designed and implemented. Although communication and information exchange through learning environments that are mediated by digital technologies have made relevant formative processes possible, the need to analyze ubiquitous learning environments has arisen as a possibility for strengthening scenarios of pedagogical practices for the educational research training in higher education and to determine if there are differences regarding the use of virtual environments.

The articulation of educational research with professional practice requires the systematization of the pedagogical experience, which is understood as an ongoing exercise in the production of critical knowledge from practice (Jara, 2012). This process implies considering and interpreting what takes place and reconstructing what has happened by engaging in the identification of elements that have intervened in the experience from a critical perspective in order to understand it from the basis of the practice itself. The articulation of educational research with professional practice has 3 stages that are sequenced and called referencing, systematization, and analysis. The initial or referencing stage involves the construction of antecedents, theoretical referents, and epistemological frameworks that are determined by the emergent issues in the pedagogical practice scenarios; the intermediate or systematization stage (Torres, 1999) embraces data collection and processing of the context, and the final or analysis stage corresponds to the triangulation, interpretation, and discussion of findings (Correa-García, 2003). This process requires technological assistance that allows access and ongoing information tracking, in addition to a formative evaluation that provides students with feedback. In the same way, the process cannot be limited to a physical and temporal space, given the fact that knowledge is built in a conscious and unconscious way at any time and place.

2. State of art

The use of technological tools in educational process began around the 1950s with distance education, in which media were positioned as an alternative for democratising learning and which allowed the extension of academic participation to different scenarios in which printed texts, manuals, and books sent via mail sealed the beginning of an education generation blessed with technological resources (Aparici, 2002). Later, towards the 1970s the concept of 1.0 formation was born, it was considered as an analogical stage characterized by unidirectional mediation through radio and television: a static network for transmitting information and knowledge in a unidirectional way (Sevillano-García, Quicios-García, & González García, 2016). Towards the early 1990s, offline learning incorporated multimodality (Díaz, 2009). CD-ROM and computer science enabled the student to interact in two ways, teacher-digital medium-student (Capacho, 2011). The great advances in the field of science and technology at a virtual educational level (E-learning) have transformed economic, educational, political, social, and cultural sectors since the early 1990s; the so called digital era has produced great development and challenges that must be taken on board in the face of the dynamics imposed by the information and knowledge society (García, 2006). The incorporation of technology in face-to-face learning processes led to blended learning (Hinojo, Aznar, & Cáceres, 2009). Similarly, the combination of electronic learning and smart mobile devices (Smartphone, iPod, Tablet, PDA) was seen, developments that allowed combining geographical mobility with virtual scenarios (Marcos, Támez, & Lozano, 2009).

2.1. Genesis and development of U-learning

Ubiquitous learning (U-learning) emerges as an inclusive learning paradigm, since it assimilates elements of each one of the modalities that were previously mentioned and, it also seeks to integrate technology in the assessment and monitoring of educational processes of the students in a natural way with a high dose of spontaneity, breaking the barriers that are framed by place and time. On the other hand, U-learning comes from the intelligent computing field, the artificial neuronal networks and the diffused logic whose main objective is that technological systems develop tasks of identifying patterns tasks in different sets of data in order to make decisions based on the optimization of processes. As an e-innovation agent, U-learning has been consolidated as an important concept in the last decade, since the technological development of mobile devices has allowed the operational focus to be the user, allowing student centered learning mediated by technology. In other words, at the beginning a computer was shared by several users, later, the use of personal computers was incorporated and, today we find that further development has led to the incorporation of ubiquitous technology, a third paradigm , which seeks to put different interconnected devices at the user’s service. Through this technological approach, the devices are integrated into people’s life; instead of intentionally interacting with only one device, technological ubiquity looks for simultaneous interaction with several devices for solving everyday tasks and, in many cases, without the person’s awareness.

Strictly focusing on U-learning scenarios, there are different studies that have focused on the definition, construction, characterization, and application of ubiquitous learning environments as a situation of total immersion in the learning process. Jones & Jo (2004) develop a U-learning model based on intelligent computing and adaptive learning; the authors point out that digital devices are, day by day, naturally embedded in every aspect of our lives, making ubiquitous learning a certainty for the future of education. The research group (I+G) incorporates the concept of adaptive learning and, in this way, builds digital systems that adjust themselves to the needs of each student based on the personalized teaching method (Paramythis & Loidl-Reisinger, 2004).

Dey (2000) and Hornby (1950) agree on considering that students are able to assimilate knowledge when it is built as part of everyday context or real environments. Within this scenario, the student’s profile and contextual information are used to collect, systematize, and evaluate data in order to respond to students’ requirements at the moment they require them. In the study conducted by Chen, & Li (2010), the student’s learning process is monitored by keeping track of his/her location, learning time, leisure time, time available to work on learning objectives and, time for group and individual work using artificial neuronal networks. Hwang & al. (2012) and Kim & al. (2011), both research teams at the «Anticipatory Computing Lab at Intel Labs» who developed an anticipatory communication model for the scientist Stephen Hawking, pointing out that systems can predict actions only with information from the context. The technological devices for forecasting the weather, transport routes and other events are commonly used today to improve quality of life. U-learning environments seek to predict the learning path of students and, in that way, anticipate guiding elements and activities that are synchronized with the suggested learning objectives. Through the interaction of students with electronic devices, it is intended to register their academic training and, in this way, to compare objectives and evaluation of learning, allowing the system to anticipate and adapt the answer so that students and teachers make decisions regarding the formative process.

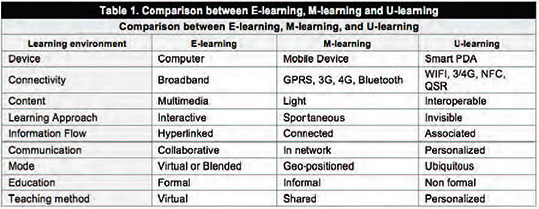

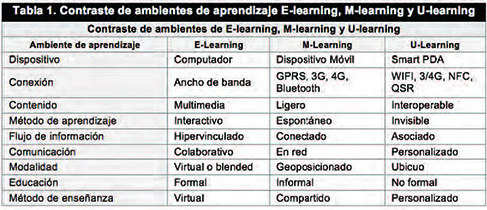

At a general level, both E-learning and U-learning have differentiating characteristics regarding the type of interaction in the construction of learning and, in the use of communication technologies. The construction of the referents in this study has led us to synthetize the characteristics of E-learning, M-learning, and U-learning based on the proposal by Laouris & Eteokleous (2005) as shown in Table 1.

Based on the characteristics of the aforementioned technological environments and the contextual needs determined by the pedagogical practice, an ad hoc U-learning environment was designed and validated at El Bosque University with the purpose of analyzing its influence in the educational research that is required from fourth-year students in the Early Childhood Education degree. This process was conducted under the assumption that assessment and monitoring are key elements that facilitate the development of autonomous skills in these students (learning to learn) in the necessary research training that is required for the completion of the thesis work. In particular, in this study we ask: Does the designed ad hoc U-learning environment for the development of research competence significantly improve the learning process of the fourth-year students of the Early Childhood Education degree at El Bosque University, compared to those who have learnt through an E-learning environment?

3. Materials and method

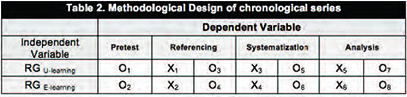

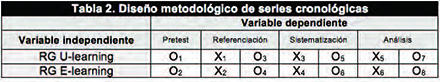

This is a quasi-experimental study with a pretest-posttest approach and a chronological series design with multiple treatments and a non-equivalent control group (Campbell & Stanley, 1995). The purpose of this study is to analyze the influence of U-learning environments on the learning outcomes of the formative research or academic training in educational research across three established moments in the process of systematizing the pedagogical experiences (referencing, systematization, and analysis), that are carried out through virtual classrooms. The students in the control group had access to the aforementioned academic training process through the E-learning virtual classrooms, while the students in the experimental group interacted with a U-learning environment. Both environments were built with the same educational research learning environments. The design in this study is shown in Table 2.

In the framework of a quasi-experimental design, the initial equivalence of the two groups is not guaranteed; this is because there is not random assignment (Hernández, Fernández, & Baptista, 2010). This is our case due to the fact that both groups were arranged in the process of student enrollment according to the criteria of academic management of the participating university and therefore, before this study started. The sample of this study is a total of 189 students (all of them women) in the fourth-year of the degree in Early Childhood Education in the Education Faculty at El Bosque University in Bogotá, Colombia. Out of the 189 students, 96 were the experimental group (U-learning environment) and 93 were the control group (E-learning environment). All of them were in academic training to become teachers through pedagogical practice and, at the same time, they take the educational research formative program. This program seeks to develop students’ competences in research in order to contribute to the building of new knowledge in different fields of the educational system and to elaborate the research document (thesis) that is a requirement for them to graduate. Moreover, in the aforementioned program research topics that are related to the professional pedagogical practice are defined. The characteristic features of U-learning environments seek to accompany the formative process in different learning scenarios. Students from an education degree were selected to participate as they were already carrying out their teaching practicum in an educational context and that allowed the two components to be articulated into the thesis process.

The systematization of experiences carried out in the U-learning environments registers in a databank the interoperation between devices, location, time synchronization, characterization of learning paths, monitoring of learning goals, and notifications regarding each user’s personalization, adjusting the goals to the student’s needs. The systematization of experiences based on the suggested parameters in the educational research processes, enables the student to take advantage of the articulation of the referencing, systematization, and analysis stages, understanding that they are a sequence of interdependent operations. During these stages, contents were structured and tools for data analysis were provided, thus establishing connections between the context and the educational research processes.

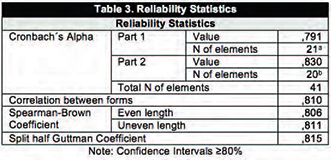

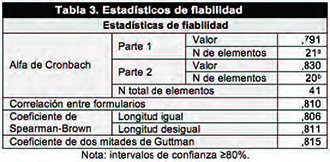

The evaluation of the research competence of students from both groups (control and experimental) was done through evaluation rubrics (Andrade, 2013), taking as reference the models of research in ubiquitous and mobile contexts in higher education (Sevillano & Vázquez, 2015). The instrument has 41 items, each with four levels of achievement that are distributed as follows: Ten value the learning outcomes linked to the referencing stage of the context, twenty to the strategies of systematization, and eleven to the analysis and reflection of the experience. The analyses conducted, Cronbach’s Alpha model and the Guttmann’s split-half reliability method, revealed that the instrument to collect data has a high internal consistency since it showed a value of a= 0.80 (Table 3).

With the purpose of guaranteeing methodological rigor, contents, activities, and interoperable learning objectives were implemented, elements that intervened in both environments and were structured from the student-centered learning theory according to the proposal by Fink (2008). After the theoretical and epistemological foundation, and the strategic planning of the methodological design, the consent form was distributed to the participating students. Later, a piloting test was carried out in three sessions: academic training, personalization, and the configuration of both learning environments proposed in this study.

As a consequence, the intervention in the learning environments to accompany the participating students in their context-situated research process took place, a process in which the first stage (referencing) was simultaneously evaluated and monitored. In the next stage the data was collected and the second phase (systematization) was implemented; later, the data analysis and the implementation of the third stage of the formative research process took place. Finally, we worked on the reflection on and publishing of the results. The field study allowed collection and storage of data in a real context. Each stage of the formative research required 12 sessions that corresponded to three academic semesters.

Prior to the confirmatory analysis of the data, the parametric assumptions of normality and the population distribution were compared through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Levene test for homogeneity variables. Regarding the inter-group analysis differences, and given the non-equivalence between them, the possibility was opened for the Student’s T-test for independent samples with parametric data, or the Mann-Whitney U test for independent groups with non-parametric data. The comparison between the dependent variables was done through the average scores obtained by the students in the evaluation rubrics at the beginning of the program (pre-test) and along the three points (referencing, systematization and analysis). The critical value assumed for the contrast hypothesis is a<0.05. The analytical treatment of the data was carried out with the IBM SPSS 23 statistic software.

4. Analysis and results

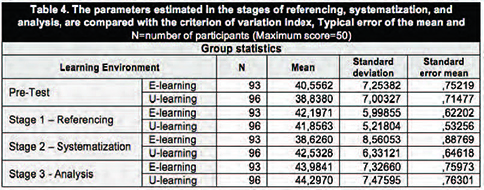

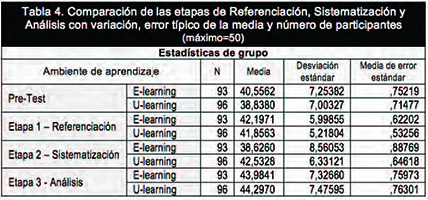

Table 4 summarizes the results that were obtained in the pretest and in the three subsequent stages of the intervention in formative research processes in both environments: U-learning (experimental group) y E-learning (control group).

Table 4 shows the means for each moment of the study (dependent variables) and for both groups. Taking into account that the coefficient on the variation does not exceed 25% in any of the dependent variables, the mean is statistically considered as a good criterion to apply the contrast hypothesis with parametric tests (Wayne, 2003). Subsequently, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was applied and the results show probability values higher than 9.05, indicating that the data of the dependent variables are adjusted to a normal distribution. The homogeneity of variance (Leven test) and the normality in the distribution of the implied variables led us to make the choice of parametric techniques for the analysis of possible differences between the control and the experimental group. The average values obtained in the diagnostic test of the pretest were similar for both groups (xp=38.83, s=7; xp=40.55. s=7.25), which was confirmed through the Student’s T-test for the independent samples, since significant differences are not observed between the two groups prior to being exposed to both experimental situations (t=-1.66; p>.05).

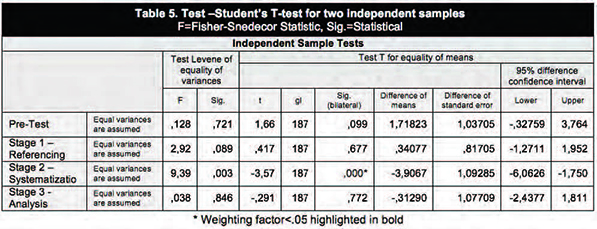

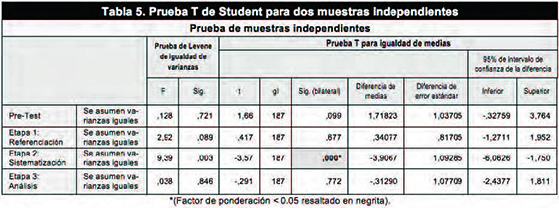

Table 5 shows the results of contrasting the differences between means for independent samples in the three stages of the intervention (referencing, systematization, and analysis). In stage 1, there was an improvement in the mean scores of the E-learning group in comparison with the experimental group U-learning (x1ee=42.19 versus x1u=41.85) with a homogenization of less dispersion in the experimental group (s1e=5.99 vs s1u= 5.21), showing that there are no statistically significant differences in the referencing stage between the two groups that interact in E-learning and U-learning environments (t=–0.42; p>.05). Both groups of students improve referencing activities in the educational research process, regardless of the learning environment in which they had interacted.

In the intermediate stage of systematization, the results indicate that there are significant differences between the means of the two groups (x2e-x2u=–3.9). In this case, the students of the control group are the ones who obtained the lowest results in the intervention, increasing the dispersion with a coefficient of variation higher than 20%; on the contrary, the experimental group (U-learning) showed a stable dispersion (Figure 1). The inter-groups analysis through Student’s T-test confirms that such differences are significant between the E-learning and U-learning groups of students in the processes of systematization of the pedagogical experiences with (t=–3.58 y p<.05), being the one with the best average scores. The results, therefore, reveal that the students who interact with a U-learning environment meaningfully improve their systematization processes in their educational research training in contrast to those who only interact in the virtual classrooms.

Finally, regarding the last stage of the intervention (analysis), the lowest mean difference is observed concerning the rest of the independent variables in the work (x3e-x3u=0.31). The comparison of means between the E-learning and U-learning groups through the Student’s T test evidences that there are no significant differences between the two groups (t=0.29 y p>.05). Therefore, the students’ achievements in the activities for the analysis of the formative research process in which they have participated, is independent of the learning environment in which they have interacted.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The intervention with U-learning environments in general shows positive results in the processes of formative research so that students learn the logic and the proper educational research activities in the pedagogical practice scenarios through the ongoing dialogue between the pervasive technology and the students’ reality at any time and place. The experimental results explain that ubiquitous learning environments facilitate contextual learning given the fact that proper content is provided at the right time and place, this in line with the statement by Chen and Li (2010). The actions performed in the U-learning environment (personalization, contextual information, comparison between evaluation and learning objectives) show that students in research formative process make the knowledge their own in a more meaningful way if pedagogical experiences are systematized in real contexts; customization, adaptation, and situational learning are fundamental factors for the technological system to anticipate and adapt the formative needs of different academic actors.

There are no significant differences between the learning outcomes achieved by students who have interacted in both environments (U-learning versus E-learning) along the referencing and analysis stages of our own formative research proposal. Nevertheless, the use of U-learning environments to systematize experiences makes a significant positive difference in the research formative process of those students who have used E-learning environments. This conclusion leads us to support the belief that ubiquitous learning environments consolidate higher education as a permanent research process when integrated with science and technological development. While it is true that virtual education generates opportunities that change realities (MEN, 2015-2016), education that is supported with U-learning environments seems to extend this picture and to affect the quality of education through assessment, monitoring, adaptation, and situational learning.

Based on the evidence and on the level of acceptance by the different participants in the study, the need to suggest and develop intervention initiatives with U-learning environments in different educational contexts is shown. This might allow comparing our findings and assessing their level of generalization. The positive results of the intervention in U-learning environments in higher education are the beginning of new studies in search of the inclusion of technology in academic formative processes with the goal of making it something so incorporated, so adaptable, so natural, so interoperable that we can use it without even thinking about it.

Finally, it is important to note that the incorporation of ubiquitous learning environments requires a significant investment of human and physical resources, which is both a limitation and a challenge. Nevertheless, the impact of the academic training is reflected in the creation of personalized and contextually adapted systems, the building of learning paths and technology that monitors student-centered learning objectives through diagnostic, formative, and summative evaluation. The development and conclusions of this study have meant an ongoing challenge of innovation and the improvement of the curriculum and of the learning and teaching process of the afore mentioned course and group of students, which has meant the consolidation of a link between technology and educational research training in the field of professional practice. The formative research processes in ubiquitous contexts strengthen the evaluation due to the assessment and ongoing monitoring of professional practice. One of the fundamental conditions for the construction and intervention of U-learning environments in the formative process, is the incorporation of experienced teachers in the research groups with pedagogical, technological, and research skills, understanding possible deductions and opening space for future research regarding the use of smart learning environments, evaluation of the impact of virtual and distance educational policies, and the construction of learning paths in formative research.

Funding agency

El Bosque University (Bogotá, Colombia). Research Vice-presidency and Faculty of Education, Early Childhood Education Program in which Doctoral Program in Education of the International School of Doctoral studies from the Department of research and methods and diagnosis collaborate with the Early Childhood Program. Research Group: Education and Investigation UNBOSQUE.

References

Andrade, H.G. (2013). Teaching with Rubrics: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. College Teaching, 53(1), 27-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930902862859

Aparici, R. (2002). Mitos de la educación a distancia y de las nuevas tecnologías. [The Myths of distance Education and New Technologies]. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 5(1), 9-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/ried.5.1.1128

Ardila, M. (2011). Calidad de la educación superior en Colombia, ¿problema de compromiso colectivo? Educación y Desarrollo Social, 6(2), 44-55. (http://goo.gl/vfhKcR) (2016-06-01).

Campbell, D.T., & Stanley, J.C. (1995). Diseños experimentales y cuasiexperimentales en la investigación social. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu Editores.

Capacho, J.R. (2011). Evaluación del aprendizaje en espacios virtuales-TIC. Barranquilla (Colombia): Universidad del Norte-ECOE Ediciones.

Chen, C.M., & Li, Y.L. (2010). Personalised Context-Aware Ubiquitous Learning System for Supporting Effective English Vocabulary Learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 18(4), 341-364. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10494820802602329

Consejo Nacional de Acreditación (2015). Lineamientos para la acreditación de programas de Pregrado. Bogotá: CNA.

Correa-García, R.I. (2003). Estrategias de investigación educativa en un mundo globalizado. [Educational Research Proposals in a Global Society]. Comunicar, 20, 53-62. (https://goo.gl/AkMAa9) (2016-06-01).

Dey, A.K. (2000). Providing Architectural Support for Building Context-Aware Applications. PhD Thesis. USA: Georgia Institute of Technology.

Díaz, J. (2009). Multimedia y modalidades de lectura: una aproximación al estado de la cuestión. [Multimedia and Reading Ways: A State of the Art]. Comunicar, 33, 213-219. https://doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-03-013

Fink, D. (2008). Evaluating Teaching: A New Approach to an Old Problem. Resources Network in Higher Education for Faculty, 26, 3-21. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

García, F.A. (2006). Una visión actual de las comunidades de «e-learning». [A Current View of The e-learning Communities]. Comunicar, 27, 143-148. (http://goo.gl/VAaAiu) (2016-07-05).

Hernández, R., Fernández-Collado, C., & Baptista, P. (2010). Metodología de la investigación. México: McGraw-Hill.

Herrera, J.D. (2013). Pensar la educación, hacer investigación. Bogotá: Universidad de la Salle.

Hinojo, F.J., Aznar, I., & Cáceres, M.P. (2009). Percepciones del alumnado sobre el blended learning en la universidad [Student's Perceptions of Blended Learning at University]. Comunicar, 33(XVII), 165-174. https://dx.doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-03-008

Hornby, A.S. (1950). The Situational Approach in Language Teaching. English Language Teaching, 4, 98-104. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/IV.4.98

Hwang, I., Jang, H., Park, T., Choi, A., Lee, Y., Hwang, C., & Song, J. (2012). Leveraging Children’s Behavioral Distribution and Singularities in New Interactive Environments: Study in Kindergarten Field Trips. 10th International Conference on Pervasive Computing, 39-56. Newcastle, UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31205-2_3

Jara, O. (2012). Sistematización de experiencias, investigación y evaluación: Aproximaciones desde tres ángulos. The International Journal for Global and Development Education Research, 1, 56-70. (http://goo.gl/6bpdm2) (2016-03-02).

Jones, V., & Jo, J.H. (2004). Ubiquitous Learning Environment: An Adaptive Teaching System Using ubiquitous technology. In R. Atkinson, C. McBeath, D. Jonas-Dwyer, & R. Phillips (Eds.), Beyond the comfort Zone: Proceedings of the 21st ASCILITE Conference (pp. 468-474). Perth, 5-8 December (https://goo.gl/HUHWtN) (2016-05-07).

Kim, B., Ha, J.Y., Lee, S., Kang, S., Lee, Y., Rhee, Y..., & Song, J. (2011). AdNext: A Visit-pattern-Aware Mobile Advertising System for Urban Commercial Complexes. In Proceedings of the 12th Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems and Applications (pp. 7-12). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2184489.2184492

Laouris, Y., & Eteokleous, N. (2005). We Need an Educationally Relevant Definition of Mobile Learning. In Proceedings of the 4th World Conference on Mobile Learning. USA: Neuroscience & Technology Institute Cyprus. (http://goo.gl/zWzanm) (2016-02-15).

Marcos, L., Támez, R., & Lozano, A. (2009). Aprendizaje móvil y desarrollo de habilidades en foros asincrónicos de comunicación [Mobile Learning as a Tool for the Development of Communication Skills in Virtual Discussion Board]. Comunicar, 33(XVII), 93-100. https://dx.doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-02-009

Martínez, P., Pérez, J., & Martínez, M. (2016). Las TIC y el entorno virtual para la tutoría universitaria. Educación XXI, 19(1), 287-310. https://dx.doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.13942

Ministerio de Educación Nacional (2015-2016). Calidad en educación superior camino a la prosperidad. Bogotá: MEN. (http://goo.gl/4OIc7x) (2016-02-14).

Paramythis, A., & Loidl-Reisinger, S. (2004). Adaptive Learning Environments and e-Learning Standards. Electronic Journal on e-Learning, 2(1), 181-194. (http://goo.gl/YcsFvs) (2016-02-15).

Restrepo, B. (2003). Concepto y aplicaciones de la investigación formativa, y criterios para evaluar. investigación científica en sentido estricto. Bogotá: CNA. (https://goo.gl/ahVj7P) (2016-02-13).

Sevillano, M.L., & Vázquez-Cano, E. (2015). Modelos de investigación en contextos ubicuos y móviles en Educación Superior. Educatio Siglo XXI, 33(2), 329-332.

Sevillano, M.L., Quicios-García, M.P., & González-García, J.L. (2016). Posibilidades ubicuas del ordenador portátil: percepción de estudiantes universitarios españoles [The Ubiquitous Possibilities of the Laptop: Spanish University Students’ Perceptions]. Comunicar, 46(XXIV), 87-95. https://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C46-2016-09

Torres, A. (1999). La sistematización de experiencias educativas. Reflexiones sobre una práctica reciente. Pedagogía y Saberes, 13(4), 5-16.

Velandia, C. (2014). Modelo de acompañamiento y seguimiento en ambientes U-learning. K. Gherab (Presidencia), Congreso Internacional de Educación y Aprendizaje. New York: Symposium XXI International Conference on Learning Common Ground in Lander College for Women.

Wayne, W.D. (2003). Bioestadística: Base para el análisis de ciencias de la salud. México: Limusa Wiley.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

La formación en investigación es fundamental en la calidad de la Educación Superior y en este contexto, la mediación tecnológica resulta esencial para alcanzar objetivos de aprendizaje centrados en el estudiante en cualquier momento y lugar. Se presentan los hallazgos de un estudio cuyo propósito ha sido evaluar los resultados de la investigación formativa de dos grupos de estudiantes que han interactuado en ambientes de aprendizaje E-learning y U-learning. La investigación obedece a un estudio cuasi-experimental con un diseño de series cronológicas y tratamiento múltiple, enmarcada en tres etapas definidas como referenciación, sistematización y análisis. La muestra ha estado constituida por 189 estudiantes de cuarto año de Licenciatura en Educación Infantil de la Universidad El Bosque en Bogotá, Colombia. Los resultados revelan que los ambientes U-learning fortalecen la evaluación y consolidan la investigación formativa como un proceso permanente para aprender investigación educativa por medio de la personalización, adaptación y el aprendizaje situacional, marcando diferencias significativas con respecto a los ambientes E-learning durante la etapa de sistematización. La intervención con ambientes U-learning ha traído consigo retos y oportunidades de innovación en el currículo académico, tales como el fortalecimiento del vínculo entre la evaluación y la investigación educativa en los campos de práctica profesional, así como la inclusión de la tecnología hasta convertirla en algo natural, adaptable e interoperable, de modo que los estudiantes pueden utilizarla sin tan siquiera pensar en ella.

1. Introducción

La calidad en educación es un tema trascendental que se ha incluido en las agendas gubernamentales de los países iberoamericanos en la última década. El Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2015-2016) señala que una educación de calidad es generadora de oportunidades que cambian realidades. En este panorama, la calidad de la Educación Superior se relaciona con la capacidad que tienen las instituciones universitarias para lograr que los estudiantes alcancen resultados académicos directamente relacionados con su proceso de aprendizaje y con su área de estudio, mediante la tecnología, la práctica profesional y la investigación (Ardila, 2011).

La Educación Superior debe ser en esencia un proceso permanente de investigación mediado por el desarrollo de la ciencia y de la tecnología, ya que estos elementos son fundamentales para consolidar una educación de alta calidad (Restrepo, 2003). Este proceso exige mantener un diálogo permanente entre la apropiación de saberes, su transformación y su vinculación con la práctica profesional para garantizar que los estudiantes se adapten a las condiciones y necesidades del contexto, entendiendo que la calidad de la educación está asociada a las prácticas investigativas y estas a su vez están ligadas a la búsqueda, construcción y apropiación de conocimiento (Herrera, 2013).

Es, en este contexto, donde cobra sentido la investigación formativa, concebida como el proceso investigativo que se desarrolla para que el alumno se forme para la investigación partiendo de situaciones problemáticas cercanas a su entorno curricular y profesional futuro (Restrepo, 2003). El escenario académico de nuestro trabajo y de sus participantes –estudiantes del cuarto año de la Licenciatura en Educación Infantil de la Universidad El Bosque de Bogotá, en Colombia–, necesariamente nos lleva a contemplar la investigación formativa para la formación en (aprender en) investigación educativa desde las problemáticas, planteamientos paradigmáticos y metodológicos que impone la lógica y las actividades propias de la investigación en el ámbito de la educación.

Fortalecer la relación de la investigación educativa con las prácticas profesionales es uno de los objetivos fundamentales de las instituciones de Educación Superior y es, por tanto, un elemento de esencial importancia para la generación de nuevo conocimiento. Desde esta perspectiva, se pretende que el estudiante recorra el camino de la investigación educativa mediante una praxis continua y sistemática, y así, dar cumplimiento a objetivos de aprendizaje centrados en el estudiante. La formación para la investigación debe valerse de todas aquellas acciones orientadas al proceso de «aprender a aprender» con el propósito de fortalecer y consolidar habilidades y conocimientos en los alumnos que les permitan desempeñar con éxito las actividades asociadas a la investigación científica, al desarrollo y a la innovación.

En Colombia, para 65.000 estudiantes que representan el 5% de población estudiantil de acuerdo con cifras del Consejo Nacional de Acreditación (Consejo Nacional de Acreditación, 2015), la asistencia virtual ha sido sustancial en sus procesos de formación. En el contexto del estudio presentado en este artículo, se han utilizado herramientas tecnológicas para asistir y evaluar los procesos de formación en investigación educativa, particularmente por medio de aplicaciones para la captura y edición de datos digitales, software para el análisis y sistematización de información, recursos electrónicos para los estudios bibliométricos y plataformas para la evaluación de producción científica. El desarrollo tecnológico reciente también ha permitido el acceso a bases de datos y gestores de referenciación para la formación en investigación, facilitando el acercamiento a fuentes especializadas de información (Velandia, 2014); de igual forma, el avance tecnológico ha fortalecido las redes de investigación al poner en marcha el trabajo colaborativo y la comunicación entre pares investigadores para acceder a prácticas, socializaciones y divulgaciones investigativas (Herrera, 2013). Otro factor fundamental y asociado al desarrollo tecnológico en los procesos de investigación formativa ha sido la orientación y flexibilización de la tutoría de forma sincrónica y asincrónica, lo que en términos de calidad de la educación se considera como parte primordial para el desarrollo de la competencia investigadora a través del acompañamiento formativo del alumno (Martínez, Pérez, & Martínez, 2016).

Sin embargo, para los participantes del presente trabajo que se forman como futuros profesores en Educación Infantil, existen condiciones y elementos donde los ambientes virtuales no facilitan un permanente diálogo entre la investigación educativa y la realidad del estudiante en su práctica profesional. El 54,3% de los alumnos llevan a cabo sus prácticas profesionales en zonas urbanas y rurales (Velandia, 2014), donde la conectividad se convierte en un elemento que dificulta la sistematización de la experiencia pedagógica y el seguimiento de los procesos de formación investigativa. Aunque los recursos digitales han permitido la extensión de la formación a otros escenarios más allá de las aulas de clase, aún se han de cubrir determinadas necesidades tales como el acceso a dispositivos electrónicos y la calidad de la conexión a Internet, bajo la premisa de un buen funcionamiento de las herramientas en cualquier instante y ubicación. Fortalecer el vínculo entre la tecnología y la formación en investigación en los campos de práctica docente profesional implica una reestructuración de la experiencia educativa considerando estándares reconocidos por la comunidad científica y, a su vez, debe respetar el rigor de la sistematicidad. Esta tarea exige una labor intelectual, la manifestación de habilidades y la puesta en marcha de recursos que asistan el proceso. La investigación educativa debe sistematizar la experiencia cuyo análisis es clave para la construcción del saber y el desarrollo de competencias profesionales. De acuerdo con este planteamiento y con la necesidad contextual de construir ambientes que permitan monitorear los procesos de formación investigativa en cualquier momento y lugar, se diseñó y se implementó un ambiente U-learning ad hoc. Aunque la comunicación y el intercambio de información a través de ambientes de aprendizaje mediados por tecnologías digitales han posibilitado procesos formativos pertinentes, surge la necesidad de analizar los ambientes de aprendizaje ubicuos (U-learning) como posibilidad de fortalecer los escenarios de prácticas pedagógicas para la investigación formativa en Educación Superior y determinar si existen diferencias respecto al uso de ambientes virtuales de aprendizaje.

La articulación entre la investigación educativa y la práctica profesional requiere llevar a cabo la sistematización de la experiencia pedagógica, entendida como un ejercicio permanente de producción de conocimiento crítico desde la práctica (Jara, 2012); este proceso implica considerar e interpretar lo que acontece y reconstruir lo que ha sucedido incurriendo en la identificación de elementos que han intervenido en la experiencia desde una postura crítica, para comprenderla desde la propia práctica. La articulación entre la investigación educativa y la práctica profesional comprende tres etapas secuenciadas, denominadas: referenciación, sistematización y análisis. La etapa inicial o de referenciación implica la construcción de antecedentes, referentes teóricos y marcos epistemológicos que son determinados por las problemáticas emergentes en los escenarios de prácticas pedagógicas; la etapa intermedia o de sistematización (Torres, 1999) contempla la recogida y procesamiento de los datos del contexto y la fase final o de análisis se corresponde con los procesos de triangulación, interpretación y discusión de los resultados (Correa-García, 2003). Este proceso demanda una asistencia tecnológica que permita el acceso y el registro de información permanentemente, además de una evaluación formativa que proporcione retroalimentación al alumnado. De la misma manera, el proceso no puede estar limitado a un espacio físico y temporal, pues el conocimiento se construye de manera consciente o inconsciente en cualquier momento y lugar.

2. Estado de la cuestión

El uso de herramientas tecnológicas en los procesos educativos se inicia alrededor de la década de los 50 con la educación a distancia, donde los medios de comunicación se posicionan como una alternativa para democratizar el aprendizaje al permitir extender la oferta académica a diferentes escenarios donde textos impresos, manuales y cartillas por correspondencia sellaban el inicio de una generación educativa marcada con recursos tecnológicos (Aparici, 2002). Posteriormente, hacia los años 70 nace el concepto de formación 1.0, considerada como una etapa analógica caracterizada por la mediación unidireccional a través de la radio y la televisión; una red estática transmisora de información y conocimiento de manera unidireccional (Sevillano, Quicios-García, & González-García, 2016). A principios de la década de los 90 el aprendizaje offline incorpora la multimedialidad (Díaz, 2009), el CD-ROM y la informática, posibilitando al estudiante interactuar en doble vía, docente-medio digital-alumno (Capacho, 2011). Los grandes avances en materia de ciencia y tecnología a nivel de educación virtual (E-learning) han transformado sectores económicos, educativos, políticos, sociales y culturales desde principios de los años 90; la llamada era digital ha producido grandes avances y retos que se deben asumir frente a la dinámica impuesta por la sociedad de la información y el conocimiento (García, 2006). La incorporación de la tecnología en los procesos educativos presenciales dio lugar al aprendizaje combinado o blended learning (Hinojo, Aznar, & Cáceres, 2009). Similarmente, se ve la conjunción entre el electronic learning y los dispositivos móviles inteligentes (smartphone, iPod, tablet, PDA), de donde nace el concepto de mobile learning (M-learning), avances que posibilitan combinar la movilidad geográfica con la virtualidad (Marcos, Támez, & Lozano, 2009).

2.1 Génesis y desarrollo del U-learning

El aprendizaje ubicuo (U-learning) emerge como un paradigma incluyente de aprendizaje, pues asimila elementos de cada una de las modalidades anteriormente mencionadas y busca la integración de la tecnología en el acompañamiento y seguimiento de los procesos educativos de los estudiantes de manera natural y con una alta dosis de espontaneidad, rompiendo las barreras enmarcadas a un lugar o a un momento. Por otra parte, el U-learning procede de la línea de la computación inteligente, las redes neuronales artificiales y la lógica difusa cuyo objetivo es que los sistemas tecnológicos desarrollen tareas de identificación de patrones en diferentes conjuntos de datos para tomar decisiones basadas en la optimización de procesos. El U-learning como agente de e-innovación, se ha consolidado durante la última década como un concepto importante, ya que los avances tecnológicos de los dispositivos móviles han permitido que el foco de operación sea el usuario, permitiendo el aprendizaje centrado en el estudiante mediado por la tecnología. En otras palabras, en principio un ordenador era compartido por varios usuarios, posteriormente se incorporó el uso de computadores personales y hoy tenemos que el desarrollo ha desembocado en la incorporación de un tercer paradigma que es la tecnología ubicua, la cual busca poner al servicio del usuario diferentes dispositivos interconectados. Desde este planteamiento tecnológico, son los dispositivos los que se integran en la vida de las personas; en lugar de interactuar intencionadamente con un solo dispositivo, la ubicuidad tecnológica busca la interacción simultánea con diferentes dispositivos para las tareas cotidianas y, en muchas ocasiones, sin que la persona sea consciente de ello. Entrando en el escenario estrictamente del U-learning, existen diferentes estudios que se han enfocado en la definición, construcción, caracterización y aplicación de ambientes de aprendizaje ubicuo, como una situación de total inmersión en el proceso de aprendizaje. Jones y Jo (2004) desarrollan un modelo U-learning tomando como referencia la computación inteligente y el aprendizaje adaptativo; los autores señalan que los dispositivos digitales son, día a día, incluidos de manera natural en todos los aspectos de nuestras vidas, siendo el aprendizaje ubicuo una certidumbre para el futuro de la educación. El equipo de investigación (I+G) incorpora el concepto de aprendizaje adaptativo y de esta manera, construye sistemas digitales que se ajustan a las necesidades de cada estudiante a partir del método de enseñanza personalizado (Paramythis & Loidl-Reisinger, 2004).

Dey (2000) y Hornby (1950) coinciden en considerar que los estudiantes logran asimilar el conocimiento cuando este se construye formando parte de contextos cotidianos o entornos reales. Dentro de este escenario, el perfil del alumno y la información contextual se utilizan para recoger datos, sistematizarlos, evaluarlos y dar respuesta a los requerimientos del alumno en el momento que lo requiera. En la investigación llevada a cabo por Chen y Li (2010), el proceso de aprendizaje del estudiante se monitorea registrando su ubicación, el tiempo de avance en el aprendizaje, el tiempo de ocio, el tiempo del que dispone para trabajar en objetivos de aprendizaje y el tiempo de trabajo grupal e individual utilizando redes neuronales artificiales.

Hwang y otros (2012), y Kim y otros (2011), equipos de trabajo del Departamento de Computación Anticipatoria del Laboratorio Intel Labs que desarrollaron el modelo anticipatorio de comunicación para el científico Stephen Hawking, señalan que los sistemas pueden predecir acciones solo con la información del contexto. Los dispositivos tecnológicos para predecir el clima, las rutas de transporte y otros eventos son comúnmente utilizados hoy en día para mejorar la calidad de vida. En los ambientes U-learning se pretende predecir la ruta de aprendizaje de los estudiantes y así anticipar elementos y actividades de formación que estén en sintonía con los objetivos de aprendizaje propuestos. A lo largo de la interacción de los alumnos con dispositivos electrónicos, se pretende registrar el avance en su formación y, de esta manera, llevar a cabo una comparación entre objetivos y evaluación del aprendizaje, permitiendo que el sistema anticipe y adapte la respuesta para que estudiantes y docentes tomen decisiones frente a los procesos formativos.

A nivel general, los ambientes E-learning y U-learning poseen características diferenciadoras respecto al tipo de interacción en la construcción del aprendizaje y en la utilización de tecnologías de comunicación. La construcción de los referentes de esta investigación nos ha llevado a sintetizar las características del E-learning, M-learning y U-learning a partir de lo propuesto por Laouris y Eteokleous (2005) como se refleja en la Tabla 1.

De acuerdo con los rasgos característicos de los ambientes tecnológicos mencionados y con las necesidades contextuales determinadas por las prácticas de profesionalización pedagógica, se diseñó y se validó un ambiente de aprendizaje U-learning ad hoc en la Universidad El Bosque con el propósito de analizar su influencia en la investigación educativa que se exige a los estudiantes del cuarto año de la Licenciatura en Educación Infantil; ello bajo la conjetura de que el acompañamiento y seguimiento son las claves que posibilitan a estos alumnos el desarrollo de las habilidades autónomas (aprender a aprender) en la formación para la investigación necesaria que supone la realización de su tesis de grado. En particular, con el presente trabajo nos planteamos: ¿el ambiente U-learning diseñado ad hoc para el desarrollo de la competencia investigadora mejora significativamente los aprendizajes de los discentes del cuarto curso de la Licenciatura en Educación Infantil de la Universidad El Bosque, frente a aquellos otros que han aprendido mediante un ambiente E-learning?

3. Material y método

La investigación obedece a un tipo de estudio cuasi-experimental con un enfoque pretest-postest y un diseño de series cronológicas con tratamiento múltiple y grupo de control no equivalente (Campbell & Stanley, 1995). El propósito del estudio se centra en analizar la influencia de los ambientes de aprendizaje U-learning en los resultados de aprendizaje de la formación investigativa o formación en investigación educativa durante tres momentos definidos en el proceso de sistematización de las experiencias pedagógicas (referenciación, sistematización y análisis) llevados a cabo con la mediación de aulas virtuales. Los estudiantes del grupo de control tuvieron acceso al proceso de formación citado a través de aulas virtuales definido en el estudio como un ambiente E-learning, mientras que los discentes del grupo experimental interactuaron con el ambiente U-learning; los dos ambientes se construyeron bajo los mismos objetivos de aprendizaje en investigación educativa. El diseño de esta investigación se plasma en la Tabla 2.

En el marco del diseño cuasi-experimental no se garantiza la equivalencia inicial de los grupos, ya que no hay una asignación aleatoria (Hernández & al., 2010) y este es nuestro caso, ya que ambos grupos se han configurado en el proceso de matriculación del alumnado según los criterios de gestión académica de la universidad participante y, por tanto, antes del desarrollo del trabajo. La muestra de estudio está constituida por un total de 189 estudiantes (todas mujeres) del cuarto año de la Licenciatura en Pedagogía Infantil de la Facultad de Educación en la Universidad El Bosque de Bogotá, Colombia, perteneciendo 96 de ellas al grupo experimental (ambiente U-learning) y 93 al grupo de control (ambiente E-learning). Todas las participantes se forman como profesoras a través de las prácticas pedagógicas y, a su vez, cursan parte del programa de formación para la investigación educativa; este programa pretende que las estudiantes desarrollen competencias en investigación para contribuir a la construcción de nuevo conocimiento en diferentes ramas del sistema educativo, y a su vez, desarrollen su trabajo de investigación (tesis de grado) como requisito indispensable para graduarse. Además, en dicho programa se definen temas de investigación que estén ligados a las prácticas pedagógicas profesionales. Los rasgos característicos de los ambientes de aprendizaje U-learning procuran acompañar procesos de formación en diferentes escenarios de aprendizaje. Se optó por discentes de licenciatura como participantes del estudio, debido a su labor educativa en contextos de práctica pedagógica que están articulados con los procesos de formación investigativa.

La sistematización de experiencias llevada a cabo en los ambientes de aprendizaje U-learning registra en un banco de datos la interoperación entre dispositivos, ubicación, tiempo de sincronización, caracterización de rutas de aprendizaje, seguimiento a metas de aprendizaje y notificaciones respecto a la personalización de cada usuario, ajustándose a las necesidades del estudiante. La sistematización de experiencias establecida desde los parámetros propuestos en los procesos de la investigación educativa permite que el estudiante aproveche la coyuntura entre las etapas de referenciación, sistematización y análisis, entendiendo que son una secuencia de operaciones interdependientes. Durante estas etapas se estructuraron contenidos y se proporcionaron herramientas de análisis de información, estableciendo así conexiones entre el contexto y los procesos de investigación educativa.

La valoración de la competencia investigativa de las estudiantes de ambos grupos se realizó mediante rúbricas de evaluación (Andrade, 2013), tomando como referencia los modelos de investigación en contextos ubicuos y móviles en Educación Superior (Sevillano & Vázquez, 2015). El instrumento consta de 41 ítems, cada uno con cuatro niveles de logro distribuidos de esta forma: 10 valoran resultados de aprendizaje vinculados con la etapa de referenciación del contexto, 20 con las estrategias de sistematización y 11 con las del análisis y la reflexión de la experiencia. Los análisis realizados, modelo Alfa de Cronbach y el método de las dos mitades aleatorias de Guttman, revelan que el instrumento de recogida de información utilizado goza de una alta consistencia interna al arrojar un valor de a=0.80 (Tabla 3).

Con el objetivo de garantizar el rigor metodológico, se implementaron contenidos, actividades y objetivos de aprendizaje interoperables, los cuales intervinieron en ambos ambientes y fueron estructurados desde la teoría del aprendizaje centrado en el estudiante de acuerdo a la propuesta de Fink (2008). Tras la fundamentación teórica y epistemológica y la planificación estratégica del diseño metodológico, se procedió a la aplicación del consentimiento informado a las alumnas participantes. Posteriormente, se llevó a cabo la prueba piloto desarrollada en tres sesiones de capacitación, personalización y configuración con los dos ambientes de aprendizaje propuestos en el estudio.

En consecuencia, se llevó a cabo la intervención de los ambientes de aprendizaje para acompañar a las estudiantes participantes en su proceso de investigación en el contexto de ocurrencia, donde se evaluó y se monitorizó simultáneamente la primera etapa de formación investigativa (referenciación). En la siguiente etapa se procedió a la recogida de información y puesta en marcha de la segunda fase de investigación (sistematización); posteriormente, se llevó a cabo el análisis de datos y la aplicación de la tercera etapa del proceso de investigación formativa. Finalmente, se trabajó en la reflexión y divulgación de los resultados. El estudio de campo permitió recopilar y almacenar datos en el contexto real. Cada etapa de investigación formativa requirió 12 sesiones, correspondiente a tres semestres académicos.

Previo al análisis confirmatorio de los datos, se contrastaron los supuestos paramétricos de normalidad y distribución poblacional a través de la prueba de bondad y ajuste de Kolmogorov-Smirnov, y de homogeneidad de las varianzas optando por la prueba de Levene. Respecto al análisis de diferencias inter-grupos y dada la no equivalencia entre los mismos, se dejó abierta la posibilidad de la prueba T-Student para muestras independientes con datos paramétricos o la prueba de U de Mann-Whitney para grupos independientes con datos no paramétricos. Se realizó la comparación entre las variables dependientes a través de las puntuaciones medias obtenidas por las estudiantes en las rúbricas de evaluación al iniciar el programa (pretest) y durante los tres momentos del mismo (referenciación, sistematización y análisis). El valor crítico que se ha asumido para el contraste de hipótesis es a<0.05. El tratamiento analítico de los datos se ha llevado a cabo con el software estadístico IBM SPSS 23.

4. Análisis y resultados

La Tabla 4 sintetiza los resultados obtenidos en el pretest y en las tres etapas posteriores de la intervención en los procesos de investigación formativa en ambos ambientes de aprendizaje: U-learning (grupo experimental) y E-learning (grupo de control).

En la Tabla 4 se representan las medias de cada uno de los momentos del estudio (variables dependientes) y para ambos grupos; teniendo en cuenta que el coeficiente de variación no supera el 25% en ninguna de las variables dependientes, se considera que la media es un buen criterio estadístico para aplicar el contraste de hipótesis con pruebas paramétricas (Wayne, 2003). Posteriormente, se aplicó la prueba de normalidad de Kolmogorov-Smirnov y los resultados evidencian valores de probabilidad mayores a 0.05, lo que indica que los datos de las variables dependientes se ajustan a una distribución normal. La homogeneidad de las varianzas (prueba de Levene) y la normalidad en las distribuciones de las variables implicadas llevaron a la elección de técnicas paramétricas para el análisis de posibles diferencias entre los grupos de control y experimental. Los valores promedio obtenidos en la prueba diagnóstica del pretest fueron similares para ambos grupos (xp=38.83, s=7; xp=40.55. s=7.25), lo que se confirma mediante la prueba T-Student para muestras independientes al no observarse diferencias significativas de partida entre los grupos antes de ser sometidos a ambas situaciones experimentales (t=–1.66; p>.05).

En la Tabla 5 se indican los resultados de contraste de las diferencias entre medias para muestras independientes en las tres etapas de intervención (referenciación, sistematización y análisis). En la etapa 1 se ha producido una mejora en las puntuaciones medias del grupo E-learning respecto al grupo experimental U-learning (x1e=42.19 versus x1u=41.85) con una homogenización de menor dispersión por parte del grupo experimental (s1e=5.99 vs s1u=5.21) reflejando que no hay diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la etapa de referenciación entre los grupos que interactúan en ambientes de aprendizaje E-learning y U-learning (t=–0.42; p>.05). Ambos grupos de estudiantes mejoran las actividades de referenciación en los procesos de investigación educativa, independientemente del ambiente de aprendizaje con el que han interactuado.

En la etapa intermedia de sistematización, los resultados indican que sí hay diferencias entre las medias de los grupos (x2e-x2u=–3.9). En este caso son las alumnas del grupo de control quienes obtienen los resultados más bajos de la intervención, aumentando la dispersión con un coeficiente de variación mayor al 20%; por el contrario, el grupo experimental (U-learning) presentó una dispersión estable (Figura 1). El análisis inter-grupos a través de la prueba T-Student confirma que tales diferencias son significativas entre las estudiantes de los grupos E-learning y U-learning en los procesos de sistematización de experiencias pedagógicas con (t=–3.58 y p<.05), siendo estas últimas quienes han obtenido mejores puntuaciones medias. Los resultados, por tanto, revelan que las alumnas que interactúan con un ambiente U-learning mejoran significativamente sus procesos de sistematización en su formación para la investigación educativa respecto a quienes interactúan solamente con aulas virtuales.

Finalmente, en cuanto a la última etapa de la intervención (analítica), se observa la diferencia de medias más baja respecto al resto de las variables dependientes del trabajo (x3e-x3u=0.31); La comparación de medias entre los grupos E-learning y U-learning mediante la prueba T-Student, evidencia que no se producen diferencias significativas entre ambos (t=0.29; p>.05). Por ende, los logros de las alumnas en las actividades de análisis del proceso de investigación formativa en el que han participado, es independiente del ambiente de aprendizaje con el que han interactuado.

5. Discusión y conclusiones

La intervención con los ambientes U-learning, en general, arroja resultados positivos en los procesos de la investigación formativa para que los estudiantes aprendan la lógica y las actividades propias de la investigación educativa en los escenarios de prácticas pedagógicas mediante el diálogo permanente entre tecnología pervasiva y la realidad del discente en cualquier momento y lugar. Los resultados experimentales justifican que los ambientes de aprendizaje ubicuos facilitan el aprendizaje contextual si se les proporciona el contenido apropiado, en el momento adecuado y en el lugar indicado, coincidiendo con el planteamiento de Chen y Li (2010). Las acciones realizadas en el ambiente U-learning (personalización, información contextual, comparación entre evaluación y objetivos de aprendizaje) reflejan que los estudiantes en formación investigativa apropian el conocimiento de manera más significativa si las experiencias pedagógicas se sistematizan en contextos reales; la personalización, la adaptación y el aprendizaje situacional son factores fundamentales para que el sistema tecnológico se anticipe y se adapte a las necesidades de formación de los diferentes actores académicos.

No existen diferencias significativas entre los resultados de aprendizaje logrados por los alumnos que han interactuado en ambos ambientes (U-learning versus E-learning) durante las etapas de referenciación y de análisis de nuestra propuesta de investigación formativa. Sin embargo, el uso de ambientes U-learning para la sistematización de experiencias marca una diferencia significativa positiva en la formación investigativa de las estudiantes con respecto a aquellas otras que han utilizado ambientes E-learning. Esta conclusión nos lleva a apoyar la creencia de que los ambientes ubicuos de aprendizaje consolidan la Educación Superior como un proceso de investigación permanente vinculado al desarrollo de la ciencia y de la tecnología. Si bien la educación virtual es generadora de oportunidades que cambian realidades (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2015-2016), la educación asistida con ambientes U-learning parece extender este panorama e incide en la calidad de la educación a través del acompañamiento, seguimiento, adaptación y aprendizaje situacional.

Basados en la evidencia y apoyados en la aceptación por parte de los actores de la investigación, se refleja la necesidad de plantear y desarrollar iniciativas de intervención con ambientes U-learning en diferentes contextos de formación; ello permitirá contrastar nuestros hallazgos y valorar el nivel de generalización de los mismos. Los resultados positivos de la intervención en los ambientes U-learning en Educación Superior, constituyen la génesis de nuevas investigaciones en busca de la inclusión de la tecnología en la formación hasta convertirla en algo tan incorporado, adaptable, natural e interoperable que podamos aplicarla sin tan siquiera pensar en ella.

Finalmente, es importante destacar que la incorporación de los ambientes ubicuos de aprendizaje requiere una alta inversión en recursos humanos y materiales, lo que, a su vez, es una limitación y un desafío. No obstante, el impacto de la formación se refleja en la creación de sistemas con personalización y adaptación contextual, construcción de rutas de aprendizaje y tecnología que monitorea los objetivos centrados en el estudiante por medio de una evaluación diagnóstica, formativa y sumativa. El desarrollo y las conclusiones de este trabajo han supuesto un reto permanente de innovación y mejora en el currículo y en el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje del citado curso y grupo de estudiantes que se ha traducido en la consolidación del vínculo entre la tecnología y la formación para investigación educativa en los campos de práctica profesional. Los procesos de investigación formativa en contextos ubicuos fortalecen la evaluación debido al acompañamiento y seguimiento permanente en dichos campos. Una de las condiciones fundamentales para la construcción e intervención de ambientes U-learning en la formación, es la incorporación de profesionales a los grupos de investigación con habilidades pedagógicas, tecnológicas e investigativas, concibiendo posibles deducciones y abriendo la brecha a futuras investigaciones en torno a la aplicación de ambientes inteligentes de aprendizaje, evaluación del impacto de políticas de educación virtual y a distancia y la construcción de rutas de aprendizaje en investigación formativa.

Apoyos

Este trabajo ha recibido apoyo de la Universidad El Bosque (Bogotá, Colombia); la Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones y la Facultad de Educación en el programa Pedagogía Infantil en el que colabora el Departamento de Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación de la Universidad de Murcia (España), a través de su programa de Doctorado en Educación de la Escuela Internacional de Doctorado; y el Grupo de Investigación: Educación e Investigación UNBOSQUE Colciencias.

Referencias

Andrade, H.G. (2013). Teaching with Rubrics: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. College Teaching, 53(1), 27-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930902862859

Aparici, R. (2002). Mitos de la educación a distancia y de las nuevas tecnologías. [The Myths of distance Education and New Technologies]. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 5(1), 9-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/ried.5.1.1128

Ardila, M. (2011). Calidad de la educación superior en Colombia, ¿problema de compromiso colectivo? Educación y Desarrollo Social, 6(2), 44-55. (http://goo.gl/vfhKcR) (2016-06-01).

Campbell, D.T., & Stanley, J.C. (1995). Diseños experimentales y cuasiexperimentales en la investigación social. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu Editores.

Capacho, J.R. (2011). Evaluación del aprendizaje en espacios virtuales-TIC. Barranquilla (Colombia): Universidad del Norte-ECOE Ediciones.

Chen, C.M., & Li, Y.L. (2010). Personalised Context-Aware Ubiquitous Learning System for Supporting Effective English Vocabulary Learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 18(4), 341-364. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10494820802602329

Consejo Nacional de Acreditación (2015). Lineamientos para la acreditación de programas de Pregrado. Bogotá: CNA.

Correa-García, R.I. (2003). Estrategias de investigación educativa en un mundo globalizado. [Educational Research Proposals in a Global Society]. Comunicar, 20, 53-62. (https://goo.gl/AkMAa9) (2016-06-01).

Dey, A.K. (2000). Providing Architectural Support for Building Context-Aware Applications. PhD Thesis. USA: Georgia Institute of Technology.

Díaz, J. (2009). Multimedia y modalidades de lectura: una aproximación al estado de la cuestión. [Multimedia and Reading Ways: A State of the Art]. Comunicar, 33, 213-219. https://doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-03-013

Fink, D. (2008). Evaluating Teaching: A New Approach to an Old Problem. Resources Network in Higher Education for Faculty, 26, 3-21. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

García, F.A. (2006). Una visión actual de las comunidades de «e-learning». [A Current View of The e-learning Communities]. Comunicar, 27, 143-148. (http://goo.gl/VAaAiu) (2016-07-05).

Hernández, R., Fernández-Collado, C., & Baptista, P. (2010). Metodología de la investigación. México: McGraw-Hill.

Herrera, J.D. (2013). Pensar la educación, hacer investigación. Bogotá: Universidad de la Salle.

Hinojo, F.J., Aznar, I., & Cáceres, M.P. (2009). Percepciones del alumnado sobre el blended learning en la universidad [Student's Perceptions of Blended Learning at University]. Comunicar, 33(XVII), 165-174. https://dx.doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-03-008

Hornby, A.S. (1950). The Situational Approach in Language Teaching. English Language Teaching, 4, 98-104. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/IV.4.98

Hwang, I., Jang, H., Park, T., Choi, A., Lee, Y., Hwang, C., & Song, J. (2012). Leveraging Children’s Behavioral Distribution and Singularities in New Interactive Environments: Study in Kindergarten Field Trips. 10th International Conference on Pervasive Computing, 39-56. Newcastle, UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31205-2_3

Jara, O. (2012). Sistematización de experiencias, investigación y evaluación: Aproximaciones desde tres ángulos. The International Journal for Global and Development Education Research, 1, 56-70. (http://goo.gl/6bpdm2) (2016-03-02).

Jones, V., & Jo, J.H. (2004). Ubiquitous Learning Environment: An Adaptive Teaching System Using ubiquitous technology. In R. Atkinson, C. McBeath, D. Jonas-Dwyer, & R. Phillips (Eds.), Beyond the comfort Zone: Proceedings of the 21st ASCILITE Conference (pp. 468-474). Perth, 5-8 December (https://goo.gl/HUHWtN) (2016-05-07).

Kim, B., Ha, J.Y., Lee, S., Kang, S., Lee, Y., Rhee, Y..., & Song, J. (2011). AdNext: A Visit-pattern-Aware Mobile Advertising System for Urban Commercial Complexes. In Proceedings of the 12th Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems and Applications (pp. 7-12). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2184489.2184492

Laouris, Y., & Eteokleous, N. (2005). We Need an Educationally Relevant Definition of Mobile Learning. In Proceedings of the 4th World Conference on Mobile Learning. USA: Neuroscience & Technology Institute Cyprus. (http://goo.gl/zWzanm) (2016-02-15).

Marcos, L., Támez, R., & Lozano, A. (2009). Aprendizaje móvil y desarrollo de habilidades en foros asincrónicos de comunicación [Mobile Learning as a Tool for the Development of Communication Skills in Virtual Discussion Board]. Comunicar, 33(XVII), 93-100. https://dx.doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-02-009

Martínez, P., Pérez, J., & Martínez, M. (2016). Las TIC y el entorno virtual para la tutoría universitaria. Educación XXI, 19(1), 287-310. https://dx.doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.13942

Ministerio de Educación Nacional (2015-2016). Calidad en educación superior camino a la prosperidad. Bogotá: MEN. (http://goo.gl/4OIc7x) (2016-02-14).

Paramythis, A., & Loidl-Reisinger, S. (2004). Adaptive Learning Environments and e-Learning Standards. Electronic Journal on e-Learning, 2(1), 181-194. (http://goo.gl/YcsFvs) (2016-02-15).

Restrepo, B. (2003). Concepto y aplicaciones de la investigación formativa, y criterios para evaluar. investigación científica en sentido estricto. Bogotá: CNA. (https://goo.gl/ahVj7P) (2016-02-13).

Sevillano, M.L., & Vázquez-Cano, E. (2015). Modelos de investigación en contextos ubicuos y móviles en Educación Superior. Educatio Siglo XXI, 33(2), 329-332.

Sevillano, M.L., Quicios-García, M.P., & González-García, J.L. (2016). Posibilidades ubicuas del ordenador portátil: percepción de estudiantes universitarios españoles [The Ubiquitous Possibilities of the Laptop: Spanish University Students’ Perceptions]. Comunicar, 46(XXIV), 87-95. https://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C46-2016-09

Torres, A. (1999). La sistematización de experiencias educativas. Reflexiones sobre una práctica reciente. Pedagogía y Saberes, 13(4), 5-16.

Velandia, C. (2014). Modelo de acompañamiento y seguimiento en ambientes U-learning. K. Gherab (Presidencia), Congreso Internacional de Educación y Aprendizaje. New York: Symposium XXI International Conference on Learning Common Ground in Lander College for Women.

Wayne, W.D. (2003). Bioestadística: Base para el análisis de ciencias de la salud. México: Limusa Wiley.

Document information

Published on 31/03/17

Accepted on 31/03/17

Submitted on 31/03/17

Volume 25, Issue 1, 2017

DOI: 10.3916/C51-2017-01

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?