| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | <!-- metadata commented in wiki content | ||

| + | ==Spatio-temporal point process analysis of Mexico State wildfires== | ||

| − | + | '''Luis Ramón Munive-Hernándezcbi2202800068@izt.uam.mx, luis.ramon.munive@alumnos.uacm.edu.mx<sup>a</sup>, Antonio Villanueva-Moralesavillanuevam@chapingo.mx<sup>b</sup>''' | |

| + | --> | ||

| − | + | ==Abstract== | |

| − | == | + | Wildfires are an example of a phenomenon that can be investigated using point process theory. We analyze public data from the National Forestry Commission. It consists of wildfire records, specifically their coordinates and dates of occurrence in Mexico State from 2010 to 2018. The spatial component was examined, and we found that wildfires tend to cluster. Afterwards, a time series analysis was conducted. This shows that the data comes from a stationary stochastic process. Finally, some spatio-temporal features that demonstrate the point process' regular behavior in space and time were investigated. This research could be a reference to describe wildfire behavior in a specific space and time. |

| − | < | + | |

| + | '''keywords''' Environmental statistics, point processes, spatio-temporal statistics, wildfires. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==1 Introduction== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wildfires are complex phenomena with serious socio-environmental consequences, including economic and biodiversity losses, among others. Anthropogenic factors are responsible for nearly all wildfires in Mexico State, according to data from the National Forestry Commission (Conafor, its Spanish acronym) [serieconafor] (see Figure [[#img-1|1]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-Causes donut chart-1.png|282px|Mexico State wildfire causes (2010-2018).]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 1:''' Mexico State wildfire causes (2010-2018). | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is plenty of specialized literature available on wildfires (see [rodriguez2014incendios] and [rodriguez2015incendios]). The authors of [garcia2012analisis] use a logistic regression model to assess the risk of wildfire in Puebla, Mexico, taking into account land cover, meteorological, topographic, and social variables. Using two different data sources: Conafor's open data and Modis' (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) data, the authors of [de2017spatial] show that wildfire spatial patterns in Mexico tend to cluster. The spatial and temporal relationships between Conafor's wildfire records from 2005 to 2015 and the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) were investigated [marin2018drought]. Machine learning techniques were used to determine the wildfire propensity in Mexico using Conafor's open data [hernandezprediccion]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The spatio-temporal behavior of wildfires could be critical for improving fire management strategies. The point processes approach can be used to model random events in time, space, or space-time, such as wildfires. In this study, we used point processes theory to describe the spatio-temporal behavior of wildfires in Mexico State from 2010 to 2018. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2 Point processes basic theory== | ||

| + | |||

| + | A point process is a random set in which the number of points and their locations are both random [baddeley2008analysing]. A point process could occur in any completely separable metric space <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>, such as <math display="inline">d</math>-dimensional Euclidean space <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^d</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Definition 1: The point process <math display="inline">Y</math>, with state space <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>, is a measurable mapping from a probability space <math display="inline">(\Omega , \mathcal{F}, \mathbb{P})</math> to the measure space of the point process' realizations equipped with the counting measure, <math display="inline">\left(\mathcal{Y}_{\mathcal{S}}^{\# }, \mathcal{B} \left(\mathcal{Y}_{\mathcal{S}}^{\# } \right), \mu _{\# } \right)</math>. Where <math display="inline">\mathcal{Y}_{\mathcal{S}}^{\# } = \left\lbrace \mu _{\# } : \mathcal{B}\left(\mathcal{S} \right)\rightarrow \mathbb{N} \; \middle | \; \mu _{\# }(A) < \infty , A \in \mathcal{B} \left(\mathcal{S} \right)\right\rbrace </math> is the space of all finite counting measures on a <math display="inline">\sigma </math>-algebra <math display="inline">\mathcal{B} \left(\mathcal{S} \right)</math> of subsets of <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>, <math display="inline">\mathcal{B} \left(\mathcal{Y}_{\mathcal{S}}^{\# } \right)</math> is a <math display="inline">\sigma </math>-algebra of subsets of the space <math display="inline">\mathcal{Y}_{\mathcal{S}}^{\# }</math> and <math display="inline">\mu _{\# }</math> is the counting measure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The commutative diagram in Figure [[#img-2|2]] illustrates the point process definition. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-2'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 2:''' Commutative diagram of point process definition. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The mapping <math display="inline">\varphi _A</math> takes measures <math display="inline">\mu _{\# } \in \mathcal{Y}_{\mathcal{S}}^{\# }</math> and maps them into <math display="inline">\mu _{\# } (A)</math>. As a result, the mapping <math display="inline">\varphi _A</math> in terms of the point process <math display="inline">Y</math> is <math display="inline">\varphi _A : Y(\omega , \cdot ) \mapsto Y(\omega , A)</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Furthermore, the commutative diagram reveals the equivalences: <math display="inline">Y(\omega , A) = \varphi _A \left(Y(\omega , \cdot ) \right)= Y_A(\omega )</math> and <math display="inline">Y_A^{-1} (B) = Y^{-1} \left(\varphi _A^{-1} (B) \right)</math>, for any <math display="inline">B \in \mathcal{P}\left(\mathbb{N} \right)</math>, where <math display="inline">\mathcal{P}\left(\mathbb{N} \right)</math> denotes the power set of <math display="inline">\mathbb{N}</math>, so <math display="inline">\left(\mathbb{N}, \mathcal{P} \left(\mathbb{N} \right)\right)</math> is a measurable space, [daley2007introduction], [baddeley2007spatial]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following are some fundamental properties of a point process [baddeley2007spatial]: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <li>Is additive, this is </li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>Y(\omega , A_1 \cup A_2) = Y(\omega , A_1) + Y(\omega , A_2),</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | whenever <math display="inline">A_1 \cap A_2 = \varnothing </math>, <math display="inline">A_1, A_2 \subset \mathcal{S}</math> and of course | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>Y(\omega , \varnothing ) = 0.</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <li>Is locally finite </li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\mathbb{P}\left(Y(\omega , A) < \infty \right)= 1,</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | for any <math display="inline">A \subset \mathcal{S}</math>. | ||

| + | <li>Is simple </li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\mathbb{P}\left(Y(\omega , \{ \boldsymbol{s}\} ) \leq 1\right)= 1,</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | for any point <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s} \in \mathcal{S}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | For simplification, we will write <math display="inline">Y(\omega , A) = Y(A)</math> in the foregoing. When the point process <math display="inline">Y</math> is observed, we have a point pattern denoted by <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{Y}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In order to generate models, some assumptions about a point process must be made. Stationarity and isotropy are the most important assumptions. The former refers to statistical invariance under translations, whereas the latter refers to statistical invariance under rotations [baddeley2007spatial], [baddeley2015spatial]. Nonetheless, some research on non-stationary and anisotropic processes has been conducted (see [gabriel2022mapping] and [villanueva2008modified]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Definition 2: A point process <math display="inline">Y</math> on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math> is stationary if, for any fixed <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s} \in \mathcal{S}</math>, the distribution of the process <math display="inline">Y + \boldsymbol{s}</math> is identical to the distribution of <math display="inline">Y</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===2.1 Poisson process=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The general Poisson point process in some space <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math> can be defined as follows [baddeley2007spatial], [baddeley2015spatial]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id='theorem-Poisson process def'></span>Definition 3: The Poisson process <math display="inline">Y</math> on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math> with intensity measure <math display="inline">\Lambda </math> is a point process such that: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <li>For every compact set <math display="inline">A \subset \mathcal{S}</math>, the random variable <math display="inline">Y(A) \sim \mathrm{Poisson}\left(\Lambda (A) \right)</math>. </li> | ||

| + | <li>If <math display="inline">A_1, \ldots , A_n \subset \mathcal{S}</math> are disjoint compact sets, then <math display="inline">Y(A_1), \ldots , Y(A_n)</math> are independent random variables. </li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where the intensity measure <math display="inline">\Lambda </math> is defined, for any <math display="inline">A \subset \mathcal{S}</math>, as <math display="inline">\Lambda (A) = \mathbb{E} \left(Y(A) \right)</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If the state space is <math display="inline">\mathcal{S} = \mathbb{R}^2 \times \mathbb{R}_+</math> and the expected value of the point process <math display="inline">Y</math> in <math display="inline">S \times T</math>, with <math display="inline">S \subset \mathbb{R}^2</math> and <math display="inline">T \subset \mathbb{R}_+</math>, can be written as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\mathbb{E}\left(Y(S \times T) \right)= \lambda \; \mu _{L}(S) \; \mu _{L}(T),</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math display="inline">\lambda > 0</math> and <math display="inline">\mu _L</math> is the Lebesgue measure, then we have the spatio-temporal homogeneous Poisson point process [gabriel2013stpp]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The simplest stochastic mechanism for generating point patterns is the homogeneous Poisson point process. As a data model, it is almost never plausible. Regardless, it is the fundamental reference or benchmark model of a point process [baddeley2008analysing]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The homogeneous Poisson point process is also known as complete spatial (or spatio-temporal) randomness. Additionally, the Poisson point process is stationary and isotropic [baddeley2007spatial]. | ||

| + | |||

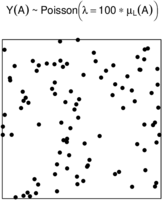

| + | Figure [[#img-3|3]] depicts a spatial point pattern generated by a homogeneous Poisson point process. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-3'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-Poisson spatial pattern-1.png|162px|Simulation of a spatial homogeneous Poisson process.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 3:''' Simulation of a spatial homogeneous Poisson process. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==3 Point pattern's data analysis== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Distances between points are a straightforward way to examine a point pattern. The most common statistics used in exploratory analysis of a point pattern are as follows. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.1 <span id='lb-3.1'></span>Empty-space function F=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math display="inline">Y</math> be a stationary point process on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>. The shortest distance between a given point <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s} \in \mathcal{S}</math> and the nearest observed point <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{y}_i \in \boldsymbol{Y}</math> is denoted as <math display="inline">\mathrm{d}(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{Y}) = \min _{i} \left\lbrace \lVert \boldsymbol{s} - \boldsymbol{y}_i \rVert \right\rbrace </math>. It is called the empty-space distance, spherical contact distance, or simply contact distance [baddeley2008analysing], [baddeley2007spatial], [baddeley2015spatial]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-4'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-picture-f945a7.png|600px|Empty-space distance illustration.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 4:''' Empty-space distance illustration. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note that | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="eq-2"></span> | ||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\mathrm{d}(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{Y}) \leq r \Leftrightarrow Y\left(B_r(\boldsymbol{s}) \right)> 0, </math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (2) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math display="inline">B_r(\boldsymbol{s})</math> is the neighborhood of radius <math display="inline">r</math> centered on <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In other words, as shown in Figure [[#img-4|4]], the empty-space distance satisfies the logical equivalence of the biconditional ([[#eq-2|2]]), <math display="inline">\mathrm{d}(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{Y}) > r \Leftrightarrow Y\left(B_r(\boldsymbol{s}) \right)= 0</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Moreover, because <math display="inline">\left\lbrace Y\left(B_r(\boldsymbol{s}) \right)> 0 \right\rbrace </math> is measurable, the event <math display="inline">\left\lbrace \mathrm{d}(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{Y}) \leq r \right\rbrace </math> is measurable, implying that the contact distance is a well-defined random element. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Definition 4: Let <math display="inline">Y</math> be a stationary point process on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>. The empty-space function <math display="inline">F</math> is the cumulative distribution function of the empty-space distance | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>F(r) = \mathbb{P}\left(\mathrm{d}(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{Y}) \leq r \right).</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math display="inline">Y</math> is a homogeneous Poisson process on <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^d</math> with intensity <math display="inline">\lambda </math>, then the empty-space function is | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>F(r) = 1 - \exp \left(- \lambda \; \mu _L \left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)\; r^d \right),</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math display="inline">r \geq 0</math>, <math display="inline">\mu _L \left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)= \frac{\pi ^{d / 2}}{\Gamma \left(\frac{d}{2} + 1 \right)}</math> denotes the volume of the unitary <math display="inline">d</math>-ball in <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^d</math> and <math display="inline">\Gamma </math> is the usual gamma function. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.2 <span id='lb-3.2'></span>Nearest-neighbour function G=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The nearest-neighbour distance, denoted by <math display="inline">\mathrm{d}_i = \min _{i \neq j} \left\lbrace \lVert \boldsymbol{y}_i - \boldsymbol{y}_j \rVert \right\rbrace </math>, is the distance between each point <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{y}_i \in \boldsymbol{Y}</math> and its nearest neighbour in the set <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{Y} | ||

| + | |||

| + | \{ \boldsymbol{y}_i \} </math>, [baddeley2008analysing], [baddeley2007spatial]. It is worth noting that <math display="inline">\mathrm{d}_i</math> can also be written as <math display="inline">\mathrm{d}_i = \mathrm{d}\left(\boldsymbol{y}_i, \boldsymbol{Y} | ||

| + | |||

| + | \{ \boldsymbol{y}_i \} \right)</math>, [baddeley2015spatial]. This distance is depicted in Figure [[#img-5|5]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-5'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-picture-35d204.png|600px|Nearest-neighbour distance illustration.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 5:''' Nearest-neighbour distance illustration. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Definition 5: Let <math display="inline">Y</math> be a stationary point process on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>. The nearest-neighbour function <math display="inline">G</math> is the cumulative distribution function of the nearest-neighbour distance | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>G(r) = \mathbb{P}\left(\mathrm{d}\left(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{Y} </math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\{ \boldsymbol{s} \} \right)\leq r \; \middle | \; \boldsymbol{s} \in \boldsymbol{Y} \right),</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math display="inline">r \geq 0</math> and <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s}</math> is any location in the state space <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math display="inline">Y</math> is a homogeneous Poisson process on <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^d</math> with intensity <math display="inline">\lambda </math>, then the nearest-neighbour function is | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>G(r) = 1 - \exp \left(- \lambda \; \mu _L \left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)\; r^d \right).</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this case, we have that <math display="inline">F(r) = G(r)</math>, i.e., under complete spatial randomness, the points of the Poisson process are independent of each other, so conditioning does not affect them. Therefore, <math display="inline">F</math> is equivalent to <math display="inline">G</math>, [baddeley2008analysing]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.3 Intensity=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The intensity function describes the first-order properties of a point process [cressie1991statistics], [diggle2013statistical]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The average number of points per spatial (or spatio-temporal) unit defines the intensity of a point process. In this regard, intensity is analogous to the expected value of a random variable [baddeley2007spatial]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Similarly, we can investigate the analogue of a point process' variance or covariance throughout the second-order properties. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As we will see in the following, the intensity measure <math display="inline">\Lambda </math> of a point process <math display="inline">Y</math> is clearly a set function, whereas the “instantaneous” intensity function <math display="inline">\lambda </math> is an atomic function. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Definition 6: Let <math display="inline">Y</math> be a point process on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>. The first-order intensity is defined as | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\lambda (\boldsymbol{s}) = \lim _{\nu \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s} \right)\to 0} \frac{\mathbb{E}\left(Y(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s}) \right)}{\nu \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s} \right)},</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math display="inline">\nu </math> is a suitable measure on <math display="inline">\left(\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{B}\left(\mathcal{S} \right)\right)</math> and <math display="inline">\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{s}</math> defines a infinitesimally small region around <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math display="inline">Y</math> is a point process on <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^d</math> with intensity measure <math display="inline">\Lambda </math>, it satisfies | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\Lambda (A) = \int _A \lambda (\boldsymbol{s}) \; \mu _L \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s} \right),</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | for some function <math display="inline">\lambda </math> and any <math display="inline">A \subset \mathbb{R}^d</math>. Then <math display="inline">\lambda </math> is called the intensity function of <math display="inline">Y</math> [baddeley2007spatial]. If <math display="inline">\lambda </math> is constant, then <math display="inline">Y</math> is said to be homogeneous, otherwise is said to be inhomogeneous [moller2003statistical]. Likewise, if the intensity function exists, we can interpret it as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\mathbb{P}\left(Y (\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s}) > 0 \right)\approx \mathbb{E} \left(Y (\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s}) \right)\approx \lambda (\boldsymbol{s}) \; \mu _L \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s} \right).</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The <math display="inline">K</math> function and pair correlation are both second-moment properties, so the second-order intensity must be defined [diggle2013statistical]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Definition 7: Let <math display="inline">Y</math> be a point process on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>. The second-order intensity is defined as | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\lambda _2(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{u}) = \lim _{\begin{matrix}\nu \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s} \right)\to 0 \\ \nu \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{u} \right)\to 0\end{matrix}} \frac{\mathbb{E}\left(Y(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s}) \; Y(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{u}) \right)}{\nu \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s} \right)\; \nu \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{u} \right)}.</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | We already have the fundamental elements for defining the following pair of second-order properties. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.4 <span id='lb-3.4'></span>K function=== | ||

| + | |||

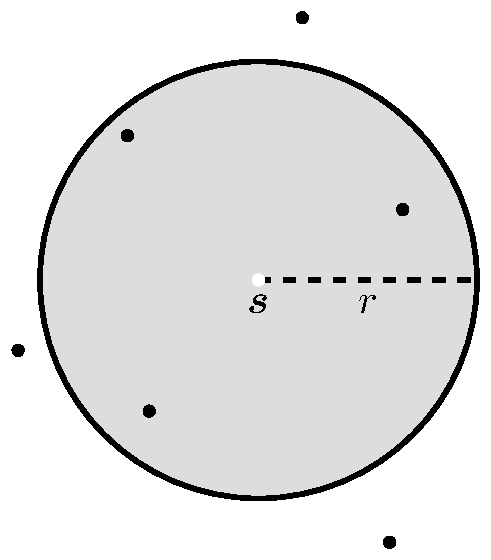

| + | The <math display="inline">K</math> function counts the number of locations within a certain radius of a given point (see Figure [[#img-6|6]]), [baddeley2015spatial], [bivand2008applied]. Ripley defined it in [ripley1977modelling]. We present the following definition [baddeley2008analysing], [diggle2013statistical]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Definition 8: Let <math display="inline">Y</math> be a stationary and isotropic point process on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math> with intensity <math display="inline">\lambda </math>. The <math display="inline">K</math> function is defined as | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>K(r) = \frac{1}{\lambda } \mathbb{E} \left(Y\left(\boldsymbol{Y} \cap B_r(\boldsymbol{s}) </math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\{ \boldsymbol{s} \} \right)\; \middle | \; \boldsymbol{s} \in \boldsymbol{Y} \right),</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math display="inline">r \geq 0</math> and <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s}</math> is any location in <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-6'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-picture-641c24.png|600px|K function illustration.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 6:''' <math>K</math> function illustration. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math display="inline">\mathcal{S} = \mathbb{R}^d</math> and the point process <math display="inline">Y</math> is assumed to be stationary, then hold <math display="inline">\lambda _2 \left(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{u} \right)= \lambda _2 \left(\boldsymbol{s} - \boldsymbol{u} \right)</math>. Also, if <math display="inline">Y</math> is isotropic, hence <math display="inline">\lambda _2(\boldsymbol{s} - \boldsymbol{u}) = \lambda _2(r)</math>, where <math display="inline">r = \lVert \boldsymbol{s} - \boldsymbol{u} \rVert </math>. These conditions implies that [cressie1991statistics], [diggle2013statistical], | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="eq-3"></span> | ||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\lambda \; K(r) = \frac{d \; \mu _L\left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)}{\lambda } \int _0^r \lambda _2 (z) \; z^{d-1} \; \mathrm{d}z. </math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (3) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The above expression provides a relationship between the <math display="inline">K</math> function and the second-order intensity under the assumptions of stationarity and isotropy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math display="inline">Y</math> is a homogeneous Poisson process on <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^d</math>, then the <math display="inline">K</math> function is [baddeley2007spatial], | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>K(r) = \mu _L\left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)\; r^d.</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.5 <span id='lb-3.5'></span>Pair correlation function g=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | In general, the pair correlation function is a quotient of probabilities; that is, the probability of observing a pair of points separated by a given distance is divided by the same probability, assuming a Poisson point process [baddeley2008analysing]. In the strictest sense, it is neither a distribution nor a correlation function [diggle2013statistical]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some authors consider the pair correlation function to be the most informative second-order property because it provides information more simply than, say, the <math display="inline">K</math> function [illian2008statistical]. We present the following definition [baddeley2007spatial], [moller2003statistical]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Definition 9: Let <math display="inline">Y</math> be a point process on <math display="inline">\mathcal{S}</math> with intensity function <math display="inline">\lambda </math> and second-moment density <math display="inline">g_2</math>. The pair correlation function <math display="inline">g</math> is defined as | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>g(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{u}) = \frac{g_2(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{u})}{\lambda (\boldsymbol{s}) \; \lambda (\boldsymbol{u})},</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | for any <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{u} \in \boldsymbol{Y}</math>, where the second-moment density is such that | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nu _{[2]}(C) = \int _C g_2(\boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{u}) \; \nu \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{s} \right)\nu \left(\mathrm{d} \boldsymbol{u} \right),</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | for any compact set <math display="inline">C \subset \mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{S}</math>, where <math display="inline">\nu </math> is a suitable measure on <math display="inline">\left(\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{B}\left(\mathcal{S} \right)\right)</math> (e.g., if <math display="inline">\mathcal{S} = \mathbb{R}^d</math>, so <math display="inline">\nu = \mu _L</math>), and <math display="inline">\nu _{[2]}(A_1 \times A_2) = \mathbb{E}\left(Y(A_1) \; Y(A_2) \right)- \mathbb{E}\left(Y\left(A_1 \cap A_2 \right)\right)</math>, with <math display="inline">A_1, A_2 \subset \mathcal{S}</math>, is the second factorial moment measure of <math display="inline">Y</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math display="inline">Y</math> is stationary and isotropic, it follows from ([[#eq-3|3]]) that [diggle2013statistical], [illian2008statistical], | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>g(r) = \frac{K'(r)}{d \; \mu _L\left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)\; r^{d - 1}}.</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

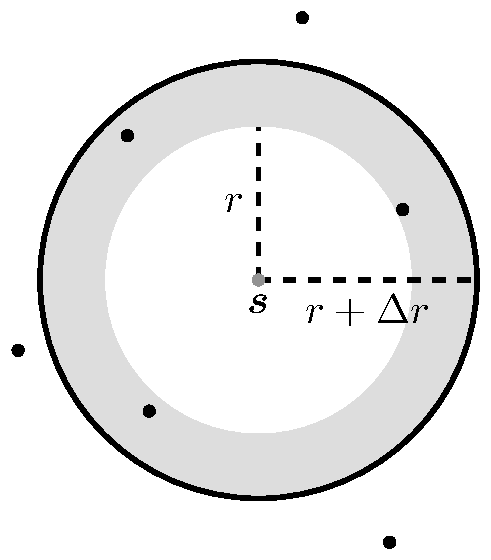

| + | We can define <math display="inline">g</math> graphically by taking two concentric circles with radius <math display="inline">r</math> and <math display="inline">r + \Delta r </math>, where <math display="inline">\Delta r</math> is a small increment, and counting the points that fall within the ring (see Figure [[#img-7|7]]), [baddeley2015spatial]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-7'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-picture-a17dd3.png|600px|Pair correlation function g illustration.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 7:''' Pair correlation function <math>g</math> illustration. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math display="inline">Y</math> is stationary and isotropic, the expected number of locations in the ring is <math display="inline">\lambda \; K (r + \Delta r) - \lambda \; K(r)</math>. Dividing it by the expected value of points assuming a Poisson process, we obtain | ||

| + | |||

| + | g_r(r) = \frac{\left(K(r + r) - K(r) \right)}{ _L\left(B_1(0) \right)\left(\left(r + r\right)^d - r^d \right)} | ||

| + | |||

| + | = \frac{K(r + r) - K(r)}{_L\left(B_1(0) \right)\left(_k=0^d dk r^d - k r^k - r^d \right)}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All binomial expansion components in the denominator of the second line in ([[#lb-3.5|3.5]]) lose significance except for <math display="inline">d \; r^{d - 1} \Delta r</math>, so | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>g_{\Delta r}(r) \approx \frac{K(r + \Delta r) - K(r)}{\mu _L\left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)\; d \; r^{d-1} \Delta r}.</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Taking the following limit, we get | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\lim _{\Delta r \to 0} g_{\Delta r} (r) \approx \lim _{\Delta r \to 0} \frac{K(r + \Delta r) - K(r)}{d \; \mu _L\left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)\; r^{d - 1} \; \Delta r} </math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> = \frac{K'(r)}{d \; \mu _L\left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)\; r^{d - 1}} </math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> = g(r). </math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math display="inline">Y</math> is a homogeneous Poisson process on <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^d</math>, then the pair correlation function is <math display="inline">g(r) = 1</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==4 Wildfires' data analysis== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Conafor data are licensed for free use (see details in https://datos.gob.mx/libreusomx). It includes wildfire geographical coordinates and dates, as well as variables like forest type affected and severity, among other things. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===4.1 Spatial analysis=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | This spatial analysis focuses on the <math display="inline">F</math> and <math display="inline">G</math> functions to determine whether the wildfire spatial point pattern is aggregated, complete spatial random, or regular. In addition, the intensity was estimated to support the evidence about point pattern behavior. | ||

| + | |||

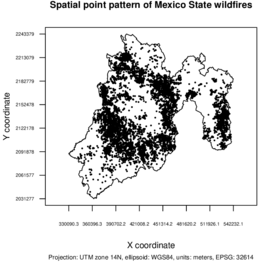

| + | Plotting the spatial point pattern is a good starting point for understanding its behavior. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figure [[#img-8|8]] shows the spatial point pattern. The wildfires do not appear to be the result of a Poisson process. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are multiple ways to prove if a point pattern comes from a Poisson point process (see [baddeley2015spatial]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-8'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-Spatial point pattern-1.png|258px|Spatial point pattern of Mexico State wildfires.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 8:''' Spatial point pattern of Mexico State wildfires. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The simulation envelopes provide a formal way to decide if the spatial pattern comes from the Poisson process. It is equivalent to performing a hypothesis test. The simulation envelopes are obtained under the assumption of a Poisson process [baddeley2008analysing], [baddeley2015spatial], [bivand2008applied]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If the empirical curve falls within the envelope, we can conclude that the point pattern comes from a Poisson process. | ||

| + | |||

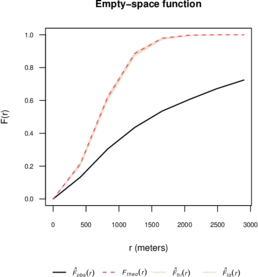

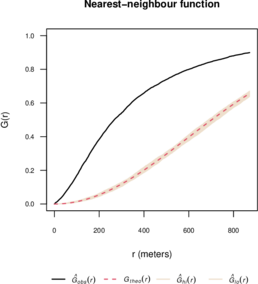

| + | Figures [[#img-9|9]] and [[#img-10|10]] show the estimated <math display="inline">F</math> and <math display="inline">G</math> functions, as well as the theoretical functions for the Poisson process and simulation envelopes. For this, we use the <code>R</code> package <code>spatstat</code> [spatstat2005]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Clearly, the spatial point pattern does not follow the Poisson model. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-9'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-F function-1.png|258px|Estimated F function and simulation envelopes.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 9:''' Estimated <math>F</math> function and simulation envelopes. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-10'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-G function-1.png|258px|Estimated G function and simulation envelopes.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 10:''' Estimated <math>G</math> function and simulation envelopes. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Figure [[#img-9|9]] note that <math display="inline">\widehat{F}_{\hbox{obs}}(r) < F_{\hbox{theo}}(r)</math>, i.e., the point pattern has longer empty-space distances than a Poisson process. This suggests a clustered point pattern [baddeley2008analysing]. While in Figure [[#img-10|10]] we observe that <math display="inline">\widehat{G}_{\hbox{obs}}(r) > G_{\hbox{theo}}(r)</math>, i.e., the point pattern has shorter nearest-neighbour distances than a Poisson model, indicating a clustered pattern [baddeley2008analysing]. | ||

| + | |||

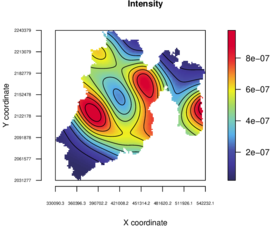

| + | Figure [[#img-11|11]] depicts the estimated intensity using a Gaussian kernel with bandwidth of 17 km. It can be used to locate wildfire hotspots. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-11'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-Intensity-1.png|270px|Estimated intensity.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 11:''' Estimated intensity. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===4.2 Time series analysis=== | ||

| + | |||

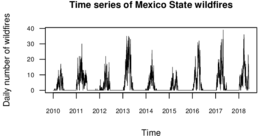

| + | This time series analysis was carried out to describe the temporal behavior of wildfires. Figure [[#img-12|12]] displays the daily number of wildfires. This immediately suggests that the wildfire time series is seasonal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-12'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-Time series-1.png|258px|Time series of Mexico State wildfires.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 12:''' Time series of Mexico State wildfires. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The augmented Dickey-Fuller test is used to prove that the time series is seasonal (see details in [timeseries2016davis]). This test is included in the <code>R</code> package <code>tseries</code> [tseries2022], where the null hypothesis is that the time series is non-stationary, against the alternative hypothesis that the time series is stationary. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table [[#table-1|1]] displays the results of the augmented Dickey-Fuller test for the wildfire time series, with a significance level of <math display="inline">\alpha = 0.05</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | ||

| + | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-1'></span>Table. 1 Augmented Dickey-Fuller test results. | ||

| + | |- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | ||

| + | | Test statistic | ||

| + | | <math>p</math>-value | ||

| + | |- style="border-bottom: 2px solid;" | ||

| + | | -5.1037 | ||

| + | | <math>< 0.01</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===4.3 Spatio-temporal analysis=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | To demonstrate clustering or regularity in a spatio-temporal point pattern, the space-time inhomogeneous <math display="inline">K</math> function (STIK) and space-time pair correlation function (STPC) can be used [gabriel2013stpp]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the assumption that the point process <math display="inline">Y</math> on <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^d</math> is second-order stationary, that is, their first-order and second-order properties are invariant under translations, the <math display="inline">K</math> function is [gabriel2009second], | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="eq-4"></span> | ||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>K(r) = d \; \mu _L \left(B_1(\boldsymbol{0}) \right)\int _0^r g(z) \; z^{d - 1} \mathrm{d} z. </math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (4) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition, a spatio-temporal point process is second-order intensity reweighted stationary and isotropic if its intensity function is bounded away from zero, and its <math display="inline">g</math> function is solely determined by <math display="inline">(u, v)</math>, where <math display="inline">u = \lVert \boldsymbol{s}_i - \boldsymbol{s}_j \rVert </math> and <math display="inline">v = \left |t_i - t_j \right |</math>, with <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{s}_i, \boldsymbol{s}_j \in \mathbb{R}^2</math>, <math display="inline">t_i, t_j \in \mathbb{R}_+</math>, [gabriel2013stpp]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math display="inline">Y</math> be a second-order intensity reweighted stationary and isotropic spatio-temporal point process with intensity <math display="inline">\lambda </math>; then, from ([[#eq-4|4]]), its STIK function is, [gabriel2013stpp], [gabriel2009second], | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>K_{ST}(u, v) = 2 \pi \int _0^v \int _0^u g(w, z) \; w \; \mathrm{d} w \; \mathrm{d} z,</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math display="inline">g(u, v) = \frac{\lambda _2(u, v)}{\lambda (\boldsymbol{s}_i, t_i) \; \lambda (\boldsymbol{s}_j, t_j)}</math> is the spatio-temporal pair correlation function <math display="inline">g</math> of <math display="inline">Y</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For any inhomogeneous spatio-temporal Poisson process with intensity bounded away from zero, | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>K_{ST}(u, v) = \pi u^2 v.</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

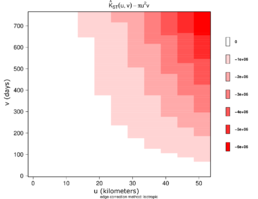

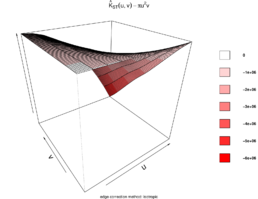

| + | Figures [[#img-13|13]] and [[#img-14|14]] show the estimated STIK function in contour and perspective plots, respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The values <math display="inline">\widehat{K}_{ST}(u, v) - \pi u^2 v</math> were plotted in order to use them as a measure of spatiotemporal aggregation or regularity. According to [gabriel2009second], <math display="inline">\widehat{K}_{ST}(u, v) - \pi u^2 v < 0</math> indicates regularity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-13'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-STIKL_image.png|258px|Estimated STIK function contour plot.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 13:''' Estimated STIK function contour plot. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-14'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-STIKL persp.png|258px|Estimated STIK function perspective plot.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 14:''' Estimated STIK function perspective plot. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

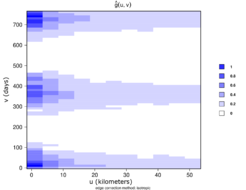

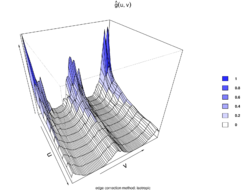

| + | Figures [[#img-15|15]] and [[#img-16|16]] illustrate estimated STPC function in contour and perspective plots, respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For a spatio-temporal Poisson point process, <math display="inline">g(u, v) = 1</math>. This reference can be used to determine how much more or less likely it is that a pair of events will occur at specific locations than in a Poisson process of equal intensity [gabriel2013stpp]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-15'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-gPCF_image.png|246px|Estimated STPC function contour plot.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 15:''' Estimated STPC function contour plot. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-16'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Review_481725695542-gPCF persp.png|246px|Estimated STPC function perspective plot.]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 16:''' Estimated STPC function perspective plot. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Surface behavior is regular; that is, there is yearly seasonality at distances less than 10 km, implying spatio-temporal regularity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==5 Conclusions and perspectives== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The spatio-temporal point pattern of Mexico State wildfires from 2010 to 2018 tends to cluster spatially, as shown by Figures [[#img-8|8]], [[#img-9|9]], [[#img-10|10]], and [[#img-11|11]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the temporal behavior is stationary, as illustrated in Figure [[#img-12|12]] and Table [[#table-1|1]], there is a yearly wildfire season during the first semester of each year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, as shown in Figures [[#img-13|13]], [[#img-14|14]], [[#img-15|15]], and [[#img-16|16]], we demonstrate that the spatio-temporal behavior is regular. This means that wildfires tend to occur in the same season and in the same areas each year. This regular spatio-temporal behavior suggests that the underlying point process is predictable in some ways. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This research could be expanded by looking into models such as spatio-temporal log-Gaussian Cox processes [taylor2013lgcp], which can be used to make spatio-temporal predictions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Acknowledgments== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Appendix== | ||

| + | |||

| + | This analysis was performed using the statistical programming language <code>R</code> [r2022]. The developed code is available in the repository: | ||

| + | |||

| + | https://github.com/LuisMunive/Spatio-temporal-point-process-analysis-of-Mexico-State-wildfires. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===BIBLIOGRAPHY=== | ||

Revision as of 03:13, 27 November 2022

Abstract

Wildfires are an example of a phenomenon that can be investigated using point process theory. We analyze public data from the National Forestry Commission. It consists of wildfire records, specifically their coordinates and dates of occurrence in Mexico State from 2010 to 2018. The spatial component was examined, and we found that wildfires tend to cluster. Afterwards, a time series analysis was conducted. This shows that the data comes from a stationary stochastic process. Finally, some spatio-temporal features that demonstrate the point process' regular behavior in space and time were investigated. This research could be a reference to describe wildfire behavior in a specific space and time.

keywords Environmental statistics, point processes, spatio-temporal statistics, wildfires.

1 Introduction

Wildfires are complex phenomena with serious socio-environmental consequences, including economic and biodiversity losses, among others. Anthropogenic factors are responsible for nearly all wildfires in Mexico State, according to data from the National Forestry Commission (Conafor, its Spanish acronym) [serieconafor] (see Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1: Mexico State wildfire causes (2010-2018). |

There is plenty of specialized literature available on wildfires (see [rodriguez2014incendios] and [rodriguez2015incendios]). The authors of [garcia2012analisis] use a logistic regression model to assess the risk of wildfire in Puebla, Mexico, taking into account land cover, meteorological, topographic, and social variables. Using two different data sources: Conafor's open data and Modis' (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) data, the authors of [de2017spatial] show that wildfire spatial patterns in Mexico tend to cluster. The spatial and temporal relationships between Conafor's wildfire records from 2005 to 2015 and the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) were investigated [marin2018drought]. Machine learning techniques were used to determine the wildfire propensity in Mexico using Conafor's open data [hernandezprediccion].

The spatio-temporal behavior of wildfires could be critical for improving fire management strategies. The point processes approach can be used to model random events in time, space, or space-time, such as wildfires. In this study, we used point processes theory to describe the spatio-temporal behavior of wildfires in Mexico State from 2010 to 2018.

2 Point processes basic theory

A point process is a random set in which the number of points and their locations are both random [baddeley2008analysing]. A point process could occur in any completely separable metric space , such as -dimensional Euclidean space .

Definition 1: The point process , with state space , is a measurable mapping from a probability space to the measure space of the point process' realizations equipped with the counting measure, . Where Failed to parse (unknown function "\middle"): {\textstyle \mathcal{Y}_{\mathcal{S}}^{\# } = \left\lbrace \mu _{\# } : \mathcal{B}\left(\mathcal{S} \right)\rightarrow \mathbb{N} \; \middle | \; \mu _{\# }(A) < \infty , A \in \mathcal{B} \left(\mathcal{S} \right)\right\rbrace }

is the space of all finite counting measures on a -algebra of subsets of , is a -algebra of subsets of the space and is the counting measure.

The commutative diagram in Figure 2 illustrates the point process definition.

| Figure 2: Commutative diagram of point process definition. |

The mapping takes measures and maps them into . As a result, the mapping in terms of the point process is .

Furthermore, the commutative diagram reveals the equivalences: and , for any , where denotes the power set of , so is a measurable space, [daley2007introduction], [baddeley2007spatial].

The following are some fundamental properties of a point process [baddeley2007spatial]:

- Is additive, this is

- Is locally finite

- Is simple

|

|

whenever , and of course

|

|

|

|

for any .

|

|

for any point .

For simplification, we will write in the foregoing. When the point process is observed, we have a point pattern denoted by .

In order to generate models, some assumptions about a point process must be made. Stationarity and isotropy are the most important assumptions. The former refers to statistical invariance under translations, whereas the latter refers to statistical invariance under rotations [baddeley2007spatial], [baddeley2015spatial]. Nonetheless, some research on non-stationary and anisotropic processes has been conducted (see [gabriel2022mapping] and [villanueva2008modified]).

Definition 2: A point process on is stationary if, for any fixed , the distribution of the process is identical to the distribution of .

2.1 Poisson process

The general Poisson point process in some space can be defined as follows [baddeley2007spatial], [baddeley2015spatial].

Definition 3: The Poisson process on with intensity measure is a point process such that:

- For every compact set , the random variable .

- If are disjoint compact sets, then are independent random variables.

Where the intensity measure is defined, for any , as .

If the state space is and the expected value of the point process in , with and , can be written as follows:

|

|

where and is the Lebesgue measure, then we have the spatio-temporal homogeneous Poisson point process [gabriel2013stpp].

The simplest stochastic mechanism for generating point patterns is the homogeneous Poisson point process. As a data model, it is almost never plausible. Regardless, it is the fundamental reference or benchmark model of a point process [baddeley2008analysing].

The homogeneous Poisson point process is also known as complete spatial (or spatio-temporal) randomness. Additionally, the Poisson point process is stationary and isotropic [baddeley2007spatial].

Figure 3 depicts a spatial point pattern generated by a homogeneous Poisson point process.

|

| Figure 3: Simulation of a spatial homogeneous Poisson process. |

3 Point pattern's data analysis

Distances between points are a straightforward way to examine a point pattern. The most common statistics used in exploratory analysis of a point pattern are as follows.

3.1 Empty-space function F

Let be a stationary point process on . The shortest distance between a given point and the nearest observed point is denoted as . It is called the empty-space distance, spherical contact distance, or simply contact distance [baddeley2008analysing], [baddeley2007spatial], [baddeley2015spatial].

| Empty-space distance illustration. |

| Figure 4: Empty-space distance illustration. |

Note that

|

|

(2) |

where is the neighborhood of radius centered on .

In other words, as shown in Figure 4, the empty-space distance satisfies the logical equivalence of the biconditional (2), .

Moreover, because is measurable, the event is measurable, implying that the contact distance is a well-defined random element.

Definition 4: Let be a stationary point process on . The empty-space function is the cumulative distribution function of the empty-space distance

|

|

If is a homogeneous Poisson process on with intensity , then the empty-space function is

|

|

where , denotes the volume of the unitary -ball in and is the usual gamma function.

3.2 Nearest-neighbour function G

The nearest-neighbour distance, denoted by , is the distance between each point and its nearest neighbour in the set , [baddeley2008analysing], [baddeley2007spatial]. It is worth noting that can also be written as , [baddeley2015spatial]. This distance is depicted in Figure 5.

| Nearest-neighbour distance illustration. |

| Figure 5: Nearest-neighbour distance illustration. |

Definition 5: Let be a stationary point process on . The nearest-neighbour function is the cumulative distribution function of the nearest-neighbour distance

|

where and is any location in the state space .

If is a homogeneous Poisson process on with intensity , then the nearest-neighbour function is

|

|

In this case, we have that , i.e., under complete spatial randomness, the points of the Poisson process are independent of each other, so conditioning does not affect them. Therefore, is equivalent to , [baddeley2008analysing].

3.3 Intensity

The intensity function describes the first-order properties of a point process [cressie1991statistics], [diggle2013statistical].

The average number of points per spatial (or spatio-temporal) unit defines the intensity of a point process. In this regard, intensity is analogous to the expected value of a random variable [baddeley2007spatial].

Similarly, we can investigate the analogue of a point process' variance or covariance throughout the second-order properties.

As we will see in the following, the intensity measure of a point process is clearly a set function, whereas the “instantaneous” intensity function is an atomic function.

Definition 6: Let be a point process on . The first-order intensity is defined as

|

|

where is a suitable measure on and defines a infinitesimally small region around .

If is a point process on with intensity measure , it satisfies

|

|

for some function and any . Then is called the intensity function of [baddeley2007spatial]. If is constant, then is said to be homogeneous, otherwise is said to be inhomogeneous [moller2003statistical]. Likewise, if the intensity function exists, we can interpret it as follows:

|

|

The function and pair correlation are both second-moment properties, so the second-order intensity must be defined [diggle2013statistical].

Definition 7: Let be a point process on . The second-order intensity is defined as

|

|

We already have the fundamental elements for defining the following pair of second-order properties.

3.4 K function

The function counts the number of locations within a certain radius of a given point (see Figure 6), [baddeley2015spatial], [bivand2008applied]. Ripley defined it in [ripley1977modelling]. We present the following definition [baddeley2008analysing], [diggle2013statistical].

Definition 8: Let be a stationary and isotropic point process on with intensity . The function is defined as

|

where and is any location in .

|

| Figure 6: function illustration. |

If and the point process is assumed to be stationary, then hold . Also, if is isotropic, hence , where . These conditions implies that [cressie1991statistics], [diggle2013statistical],

|

|

(3) |

The above expression provides a relationship between the function and the second-order intensity under the assumptions of stationarity and isotropy.

If is a homogeneous Poisson process on , then the function is [baddeley2007spatial],

|

|

3.5 Pair correlation function g

In general, the pair correlation function is a quotient of probabilities; that is, the probability of observing a pair of points separated by a given distance is divided by the same probability, assuming a Poisson point process [baddeley2008analysing]. In the strictest sense, it is neither a distribution nor a correlation function [diggle2013statistical].

Some authors consider the pair correlation function to be the most informative second-order property because it provides information more simply than, say, the function [illian2008statistical]. We present the following definition [baddeley2007spatial], [moller2003statistical].

Definition 9: Let be a point process on with intensity function and second-moment density . The pair correlation function is defined as

|

|

for any , where the second-moment density is such that

|

|

for any compact set , where is a suitable measure on (e.g., if , so ), and , with , is the second factorial moment measure of .

If is stationary and isotropic, it follows from (3) that [diggle2013statistical], [illian2008statistical],

|

|

We can define graphically by taking two concentric circles with radius and , where is a small increment, and counting the points that fall within the ring (see Figure 7), [baddeley2015spatial].

|

| Figure 7: Pair correlation function illustration. |

If is stationary and isotropic, the expected number of locations in the ring is . Dividing it by the expected value of points assuming a Poisson process, we obtain

g_r(r) = \frac{\left(K(r + r) - K(r) \right)}{ _L\left(B_1(0) \right)\left(\left(r + r\right)^d - r^d \right)}

= \frac{K(r + r) - K(r)}{_L\left(B_1(0) \right)\left(_k=0^d dk r^d - k r^k - r^d \right)}.

All binomial expansion components in the denominator of the second line in (3.5) lose significance except for , so

|

|

Taking the following limit, we get

|

|

If is a homogeneous Poisson process on , then the pair correlation function is .

4 Wildfires' data analysis

Conafor data are licensed for free use (see details in https://datos.gob.mx/libreusomx). It includes wildfire geographical coordinates and dates, as well as variables like forest type affected and severity, among other things.

4.1 Spatial analysis

This spatial analysis focuses on the and functions to determine whether the wildfire spatial point pattern is aggregated, complete spatial random, or regular. In addition, the intensity was estimated to support the evidence about point pattern behavior.

Plotting the spatial point pattern is a good starting point for understanding its behavior.

Figure 8 shows the spatial point pattern. The wildfires do not appear to be the result of a Poisson process.

There are multiple ways to prove if a point pattern comes from a Poisson point process (see [baddeley2015spatial]).

|

| Figure 8: Spatial point pattern of Mexico State wildfires. |

The simulation envelopes provide a formal way to decide if the spatial pattern comes from the Poisson process. It is equivalent to performing a hypothesis test. The simulation envelopes are obtained under the assumption of a Poisson process [baddeley2008analysing], [baddeley2015spatial], [bivand2008applied].

If the empirical curve falls within the envelope, we can conclude that the point pattern comes from a Poisson process.

Figures 9 and 10 show the estimated and functions, as well as the theoretical functions for the Poisson process and simulation envelopes. For this, we use the R package spatstat [spatstat2005].

Clearly, the spatial point pattern does not follow the Poisson model.

|

| Figure 9: Estimated function and simulation envelopes. |

|

| Figure 10: Estimated function and simulation envelopes. |

In Figure 9 note that , i.e., the point pattern has longer empty-space distances than a Poisson process. This suggests a clustered point pattern [baddeley2008analysing]. While in Figure 10 we observe that , i.e., the point pattern has shorter nearest-neighbour distances than a Poisson model, indicating a clustered pattern [baddeley2008analysing].

Figure 11 depicts the estimated intensity using a Gaussian kernel with bandwidth of 17 km. It can be used to locate wildfire hotspots.

|

| Figure 11: Estimated intensity. |

4.2 Time series analysis

This time series analysis was carried out to describe the temporal behavior of wildfires. Figure 12 displays the daily number of wildfires. This immediately suggests that the wildfire time series is seasonal.

|

| Figure 12: Time series of Mexico State wildfires. |

The augmented Dickey-Fuller test is used to prove that the time series is seasonal (see details in [timeseries2016davis]). This test is included in the R package tseries [tseries2022], where the null hypothesis is that the time series is non-stationary, against the alternative hypothesis that the time series is stationary.

Table 1 displays the results of the augmented Dickey-Fuller test for the wildfire time series, with a significance level of .

| Test statistic | -value |

| -5.1037 |

4.3 Spatio-temporal analysis

To demonstrate clustering or regularity in a spatio-temporal point pattern, the space-time inhomogeneous function (STIK) and space-time pair correlation function (STPC) can be used [gabriel2013stpp].

On the assumption that the point process on is second-order stationary, that is, their first-order and second-order properties are invariant under translations, the function is [gabriel2009second],

|

|

(4) |

In addition, a spatio-temporal point process is second-order intensity reweighted stationary and isotropic if its intensity function is bounded away from zero, and its function is solely determined by , where and , with , , [gabriel2013stpp].

Let be a second-order intensity reweighted stationary and isotropic spatio-temporal point process with intensity ; then, from (4), its STIK function is, [gabriel2013stpp], [gabriel2009second],

|

|

where is the spatio-temporal pair correlation function of .

For any inhomogeneous spatio-temporal Poisson process with intensity bounded away from zero,

|

|

Figures 13 and 14 show the estimated STIK function in contour and perspective plots, respectively.

The values were plotted in order to use them as a measure of spatiotemporal aggregation or regularity. According to [gabriel2009second], indicates regularity.

|

| Figure 13: Estimated STIK function contour plot. |

|

| Figure 14: Estimated STIK function perspective plot. |

Figures 15 and 16 illustrate estimated STPC function in contour and perspective plots, respectively.

For a spatio-temporal Poisson point process, . This reference can be used to determine how much more or less likely it is that a pair of events will occur at specific locations than in a Poisson process of equal intensity [gabriel2013stpp].

|

| Figure 15: Estimated STPC function contour plot. |

|

| Figure 16: Estimated STPC function perspective plot. |

Surface behavior is regular; that is, there is yearly seasonality at distances less than 10 km, implying spatio-temporal regularity.

5 Conclusions and perspectives

The spatio-temporal point pattern of Mexico State wildfires from 2010 to 2018 tends to cluster spatially, as shown by Figures 8, 9, 10, and 11.

While the temporal behavior is stationary, as illustrated in Figure 12 and Table 1, there is a yearly wildfire season during the first semester of each year.

Finally, as shown in Figures 13, 14, 15, and 16, we demonstrate that the spatio-temporal behavior is regular. This means that wildfires tend to occur in the same season and in the same areas each year. This regular spatio-temporal behavior suggests that the underlying point process is predictable in some ways.

This research could be expanded by looking into models such as spatio-temporal log-Gaussian Cox processes [taylor2013lgcp], which can be used to make spatio-temporal predictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo.

Appendix

This analysis was performed using the statistical programming language R [r2022]. The developed code is available in the repository:

https://github.com/LuisMunive/Spatio-temporal-point-process-analysis-of-Mexico-State-wildfires.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Document information

Published on 13/12/22

Submitted on 26/10/22

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?