(Created page with "==Summary== ====Background==== Adequate bowel preparation is an important quality indicator of colonoscopy. This study validated whether the bowel cleansing quality and aden...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 348808830 to Kang et al 2014a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 11:59, 15 May 2017

Summary

Background

Adequate bowel preparation is an important quality indicator of colonoscopy. This study validated whether the bowel cleansing quality and adenoma detection rate (ADR) could be different between two bowel preparation schedules in individuals receiving health examinations.

Methods

We enrolled individuals who had received a colonoscopy as part of the regimen for their health checkup program with split-dose phosphosoda for bowel preparation. Prior to December 31, 2012, the second dose of phosphosoda was administered at 10:00 pm before the day of the colonoscopy and the individuals were defined as the 10-pm group. After January 1, 2013, the schedule was changed to 4:00 am the same day as the colonoscopy and was defined as the 4-am group. The bowel cleansing quality was assessed using the Aronchick scale.

Results

A total of 431 individuals were included, 259 in the 10-pm group and 172 in the 4-am group. The 4-am group individuals had a higher rate of excellent or good bowel cleansing quality as compared with the 10-PM group (77.3% vs. 22%, respectively; p < 0.001). The ADR was also higher in the 4-am group than in the 10-pm group (36% vs. 25.5%, respectively; p = 0.019).

Conclusion

Modifying the time schedule of bowel preparation could improve bowel cleansing quality and increase the colonic ADR in a health management center.

Keywords

Adenoma detection rate ; Bowel cleansing quality ; Bowel preparation ; Colonoscopy

Introduction

Screening and surveillance colonoscopy can reduce the disease burden and also decreases the mortality rate of colorectal cancer [1] ; [2] ; [3] ; [4] . However, up to 9% of colorectal cancers are interval cancers and > 70% of interval cancers are attributed to missed lesions [5] . Thus, examining how to better achieve a high quality colonoscopy should be considered very important [6] ; [7] .

Proper bowel preparation is important in order to provide a high quality colonoscopy and improve the adenoma detection rate (ADR). A split-dose regimen is commonly applied for the preprocedure bowel preparation [8] ; [9] . Recent studies emphasize that the time of the second dose of administration of cleansing agent being within < 6 hours prior to colonoscopy may improve the bowel preparation quality, especially for the right-side colon [10] ; [11] ; [12] .

Because colorectal cancer screening accounts for 50% of incidence and 53% of mortality reduction, screening colonoscopy is now an important examination involved in the health checkup programs for many in the general population [4] . We thus validated whether the bowel cleansing quality and ADR could be improved by modifying the time schedules of bowel preparation in individuals receiving screening or surveillance colonoscopy as part of their health examination.

Participants and methods

We conducted this study at the health management center of the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan. The participants were enrolled between July 2012 and June 2013. During July 2012 to December 2012, the enrolled individuals received 45 mL of sodium phosphate twice (Fleet; C.B. Fleet Company Inc., Lynchburg, VA, USA) as part of their bowel preparation program at noon and at 10:00 pm on the day before their colonoscopy (10-pm group). Between January 1, 2013 and June 30, 2013 the Fleet timing schedule was changed, and the individuals received Fleet at 6:00 pm in the evening on the day before their colonoscopy and at 4:00 am on the morning of the colonoscopy (4-am group). Accordingly, this was an interventional study with a nonconcurrent control group (4-am as intervention group and 10-pm as control group). The primary endpoint was the bowel cleansing quality and the secondary endpoint was the ADR, as compared between both groups.

All the participants who received colonoscopy as part of their health checkup program with split-dose sodium phosphate for bowel preparation were enrolled. The patients were excluded from the analysis if any of the following criteria were present: (1) the colonoscopy was not completed; (2) they did not follow the bowel preparation schedule; (3) they had a history of previous intestinal surgery; (4) the patients did not receive further polypectomy in our hospital to provide the histological result.

All the participants provided signed informed consents and completed a patient report form, which recorded the actual administration time of the second dose. The colonoscopies were scheduled between 9:00 am and noon. Before their examination, participants received detailed information with regard to diet and the standard split-dose bowel preparation regimen with Fleet (1 bottle taken 2 times).

All colonoscopies were performed by experienced endoscopists. Most participants received premedication of antispasmodic agents and were sedated with intravenous propofol infusion if there were no contraindications. The smaller colonic neoplasms were removed by biopsy forceps or cold snare polypectomy during the examination. If the neoplasms were too large, a second colonoscopy was scheduled to remove those by cauterized polypectomy. All removed specimens were then sent for histological analysis.

The bowel cleansing quality was analyzed by a validated Aronchick scale [13] . It provided a qualitative global assessment based on the percentage of mucosal surface seen and the amount of liquid/solid stool present: excellent (> 95% of surface seen); good (> 90% of surface seen); fair (some semisolid stool that could be suctioned or washed away but > 90% of surface seen); and poor (< 90% of surface seen).

The location of the colorectal lesion was recorded as an anatomical location or as the distance from the anal verge. A proximal lesion was defined as a lesion located above the splenic flexure or > 40 cm above the anal verge. A distal lesion was defined as a lesion located between the descending colon and the rectum or < 40 cm above the anal verge. The definition of advanced colorectal neoplasm was polyp size > 1 cm, villous component, high-grade dysplasia, or adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, the possible confounding factors of bowel cleansing quality and colorectal neoplasm were also recorded for statistical analysis, such as body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking, alcohol, colon polyp history, and so on.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS software version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for statistical analysis. The Chi-square test and the Student t test were used for measurement of the statistical difference between the two study groups. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was taken to be significant. In order to attain statistical power at 0.8 with a two-sided test, a sample size of at least 126 individuals in each group was estimated based on achieving the primary endpoint of increasing the bowel cleansing rate from 70% to 85%. The univariate correlation and multivariate regression model were analyzed to determine the independent factors related to bowel cleansing quality and ADR.

Results

A total of 534 adults received colonoscopy with sodium phosphate as their bowel preparation during the study period. Seven participants with failure of cecal intubation and another 27 patients that did not write the actual administration time of the second dose of Fleet on their patient report form were all excluded. Seven participants who dropped out, by not returning for the polypectomy at the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, were also excluded. In addition, 43 participants (14.3%) in the 10-pm group and 26 participants (13.2%) in the 4-am group did not comply with the advised bowel preparation schedule. These participants were also excluded. Accordingly, a total of 431 participants were finally enrolled for analysis, including 259 in the 10-PM group and 172 in the 4-am group.

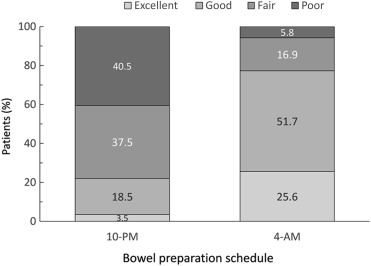

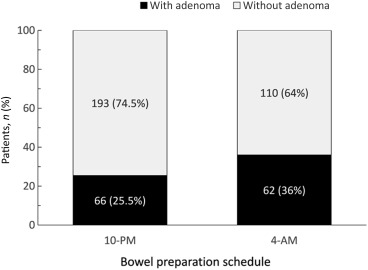

The demographic data, including risk factors of colorectal neoplasm, BMI, obesity, personal history of smoking, alcohol, colon polyp, and family history of colon cancer, were similar between the two study groups (Table 1 ). As shown in Fig. 1 , the individuals in the 4-am group had a significantly better bowel cleansing quality than those in the 10-pm group. Accordingly, 77.3% of individuals in the 4-am group had excellent or good bowel cleansing quality compared to 22% in the 10-pm group (p < 0.001). Of the 431 enrolled participants, 128 were detected as having adenoma during the colonoscopy with an overall ADR of 29.7%. The ADR in the 10-pm group was 25.5% (66/259) and it significantly improved to 36% (62/172) in the 4-am group (p = 0.019; Fig. 2 ). The mean number of adenoma in the 10-pm group was 0.45 and it increased significantly to 0.77 in the 4-am group (p = 0.008). However, the advanced ADR was not significantly different between the 10-pm and 4-am groups (4.6% vs. 4.1%, p = NS).

| 10-pm group (N = 259) | 4-am group (N = 172) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 47.7 ± 10.6 | 47.8 ± 9.6 | NS |

| Age ≥ 50 y [% (N )] | 45.2 (117) | 48.8 (84) | NS |

| Sex (M/F) | 153/106 | 102/70 | NS |

| Obesity [BMI > 27; % (N )] | 14.7 (38) | 13.4 (23) | NS |

| Central obesity [% (N )] | 37.1 (96) | 40.1 (70) | NS |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 200.7 ± 43.3 | 204.2 ± 37.8 | NS |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 131.0 ± 90.5 | 115.2 ± 72.1 | NS |

| High-density lipoprotein (mg/dL) | 53.6 ± 15.8 | 56.2 ± 17.4 | NS |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | NS |

| Smoking (N ) | 70 | 47 | NS |

| Alcohol (N ) | 104 | 76 | NS |

| Personal history of colon polyp (N ) | 21 | 25 | NS |

| Family history of colon cancer (N ) | 27 | 25 | NS |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD unless otherwise stated.

F = female; HbA1c = hemoglobin; M = male; NS = not significant (by Chi-square test or Student t test); SD = standard deviation.

|

|

|

Figure 1. The bowel cleansing quality assessed by the Aronchick scale was significantly better in the 4-am group as compared with the 10-pm group (p < 0.001, Chi-square test). |

|

|

|

Figure 2. The adenoma detection rate (ADR) was significantly higher in the 4-am group as compared with the 10-pm group (36% vs. 25.5%; p = 0.019, Chi-square test). |

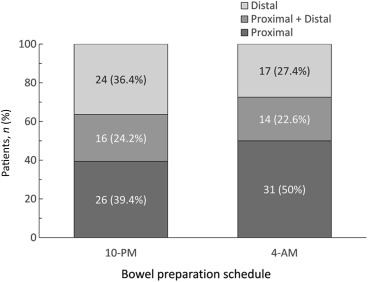

Of the 128 participants with adenoma, 57 (44.5%) of the patients' adenomas were located in the proximal colon, 41 (32.0%) in the distal colon, and the other 30 (23.4%) had both proximal and distal adenomas. The distribution of adenoma is shown in Fig. 3 —the trend shows that more proximal adenoma was found in the patients from the 4-am group as compared with the 10-pm group, but this did not attain statistical significance. A total of 26 advanced colonic neoplasms were found in 19 (4.4%) of the 128 participants, which were 22 adenomas larger than 1 cm, five were tubulovillous adenomas, and one was invasive cancer. There were no villous adenomas or high-grade dysplastic neoplasms. The advanced ADR was similar between the 10-pm and 4-am groups (4.6% vs. 4.1%; p > 0.05). In addition, large-sized adenomas and serrated adenomas were more frequently detected in the proximal colon ( Table 2 ).

|

|

|

Figure 3. The distribution of colonic adenoma between the two study groups was not statistically significant. |

| Distribution | Advanced adenoma, % (N ) | Size ≥ 1 cm | Histopathology data (N ) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA | SA/P | TVA | VA | TA with moderate dysplasia | Invasive cancer | |||

| Proximal | 69.2 (18) | 16 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Distal | 30.8 (8) | 6 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 100 (26) | 22 | 13 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

SA/P = serrated adenoma/polyp; TA = tubular adenoma; TVA = tubulovillous adenoma; VA = villous adenoma.

Furthermore, univariate and multivariate analyses were done for the possible confounding factors related to the endpoint. In the univariate analysis, the sex, preparation schedule, serum triglyceride, and serum lipoprotein were associated with the bowel cleansing quality, and age, sex, preparation schedule, obesity, diabetes, adenoma, and colon cancer history were associated with the ADR. These factors were further analyzed by multivariate analysis and shown in Table 3 . In the multivariate analysis the bowel preparation schedule, age, sex, and family history of colon cancer were all associated with the ADR, but only sex and bowel preparation schedule were independent factors related to bowel cleansing quality.

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel cleansing quality | |||

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.54 | 0.32–0.92 | 0.023 |

| Preparation schedule (4-am vs. 10-pm ) | 12.82 | 7.94–20.7 | < 0.001 |

| Serum triglyceride (per mg/dL) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.45 |

| Serum high-density lipoprotein (per mg/dL) | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.51 |

| ADR | |||

| Age (per y) | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.002 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 2.10 | 1.31–3.35 | 0.002 |

| Preparation schedule (4-am vs. 10-pm ) | 1.65 | 1.06–2.57 | 0.025 |

| Central obesity (yes vs. no) | 1.55 | 0.99–2.43 | 0.055 |

| Diabetes (yes vs. no) | 1.83 | 0.83–4.03 | 0.13 |

| Personal history of adenoma (yes vs. no) | 0.95 | 0.48–1.90 | 0.88 |

| Family history of colon cancer (yes vs. no) | 2.64 | 1.40–4.99 | 0.003 |

ADR = adenoma detection rate; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Discussion

Several items influence the quality of colonoscopy, including bowel cleansing quality, cecal intubation rate, adenoma detection rate, withdrawal time, the experience of the colonoscopist, and rates of postprocedure bleeding or perforation [6] ; [7] ; [10] ; [12] . Adequate bowel preparation seems to be one of the most important quality indicators and is related to cecal intubation rate and ADR [6] ; [7] ; [12] ; [14] ; [15] ; [16] ; [17] ; [18] ; [19] . The acceptable level of proportion of excellent or good bowel preparation is at least 90% [19] . A split dose of cleansing agents is usually used to obtain adequate bowel cleansing quality, but the time schedules are different among various studies [20] ; [21] . Some studies emphasize that the timing of the second dose of cleansing agent is important for the bowel cleansing effect [20] ; [22] . Our present study further confirmed that by merely changing the bowel preparation schedule from the 10-pm group to the 4-am group, which shortened the preparation for colonoscopy interval, resulted in a dramatic improvement of bowel cleansing quality (Fig. 1 ). Moreover, our study showed that males had a higher adenoma detection rate compared to females, even though the bowel cleansing quality was relatively poor. These results are compatible with previous studies [23] ; [24] . In both univariate and multivariate analyses, the bowel preparation schedule is an independent factor of improved bowel cleansing quality. The percentage of excellent or good bowel preparation greatly increased from 22% in the 10-pm group to 77.3% in the 4-am group.

In addition to improving bowel cleansing quality, the ADR also significantly increased from 25.5% to 36% when the bowel preparation schedules were changed from 10-pm to 4-am , as well as the mean number of adenomas per patient. However, the advanced ADR was not increased, possibly due to case number limitation or the young age of the study population. Moreover, except for the preparation schedule, the age, sex, and family history of colon cancer were also independent factors related to ADR, which is similar to other previous studies.

Our study had a much higher ADR of 29.7%, when compared with another Taiwanese study that had 15.4% [25] . The possible reasons to account for these findings include that we enrolled both screening and surveillance colonoscopy and did not exclude participants with bowel habit changes, body weight loss, colon polyp history, or family history of colorectal cancer in this study, which in turn would lead to higher ADR.

Because interval cancer tends to locate at the proximal colon, proximal adenoma detection becomes crucial to alter the tumor biology by the protection effect of colonoscopy [2] ; [26] ; [27] ; [28] ; [29] ; [30] . Studies in eastern and western countries revealed an increased prevalence of right-side adenoma or cancer with increasing age [25] ; [31] ; [32] ; [33] ; [34] . Similarly, this study showed a trend of increased proximal adenoma in older participants. Moreover, advanced or serrated adenomas were more frequently found in the proximal colon. These results emphasize the importance of bowel preparation quality as they relate to the protective effect of screening colonoscopy.

In previous studies on split-dose bowel preparation, the second dose of the cleansing agent was usually administrated between 5:00 am and 7:00 am[8] ; [11] . Considering that the duration of the Fleet effect was around 2 hours and participants needed to arrive at the health management center before 8:00 am , the time of the second dose of Fleet was set at 4:00 am in our study. One may suggest that the 4-am schedule is too early to achieve adequate bowel preparation compliance. Nevertheless, > 85% of participants in both groups could comply with the time schedule and there were no statistically significant differences.

Although this study was a hospital-based study and the sample size was relatively limited, our results demonstrated the importance of the bowel preparation schedule on bowel cleansing quality and were also linked to improvement of the ADR. It indicated that by simply changing the timing of the bowel preparation schedule we could improve the adenoma detection efficacy. However, our study has a number of limitations that should be noted. First, our study population was relatively young with a mean age < 50 years, but both advanced and proximal neoplasms are more likely to be detected in the older population. Thus, our result of no significant difference in distribution of advanced neoplasm between the study groups does not reflect the actual situation of the older high-risk population. However, a study endpoint analysis confined to the high-risk population could not be performed because the case number of participants older than 50 years did not achieve a statistical level of power. Second, the nonconcurrent control group (10-pm group) may have some selection bias. However, the possible confounding factors were not different between the study groups (Table 1 ); this may indicate that the influence of the bias was small. Third, we excluded participants receiving polyethylene glycol (Klean Prep), who may have been older. This may also underestimate adenoma prevalence. Fourth, we did not prospectively record the other modifiable risk factors for final analysis, such as diet pattern and physical activity [35] .

In summary, modifying the time schedule for bowel preparation can improve the bowel cleansing quality and increase the colonic ADR in a health management center.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1] Bureau of Health Promotion. Annual Report 2012. Taiwan: Bureau of Health Promotion.

- [2] S.J. Winawer, A.G. Zauber, M.N. Ho, M.J. O'Brien, L.S. Gottlieb, S.S. Sternberg, et al.; Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup; N Engl J Med, 329 (1993), pp. 1977–1981

- [3] A.G. Zauber, S.J. Winawer, M.J. O’Brien, I. Lansdorp-Vogelaar, M. van Ballegooijen, B.F. Hankey, et al.; Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths; N Engl J Med, 366 (2012), pp. 687–696

- [4] B.K. Edwards, E. Ward, B.A. Kohler, C. Eheman, A.G. Zauber, R.N. Anderson, et al.; Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates; Cancer, 116 (2010), pp. 544–573

- [5] H. Pohl, D.J. Robertson; Colorectal cancers detected after colonoscopy frequently result from missed lesions; Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 8 (2010), pp. 858–864

- [6] D.K. Rex, J.L. Petrini, T.H. Baron, A. Chak, J. Cohen, S.E. Deal, et al.; Quality indicators for colonoscopy; Am J Gastroenterol, 101 (2006), pp. 873–885

- [7] M.F. Kaminski, J. Regula, E. Kraszewska, M. Polkowski, U. Wojciechowska, J. Didkowska, et al.; Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer; N Engl J Med, 362 (2010), pp. 1795–1803

- [8] L.B. Cohen; Split dosing of bowel preparations for colonoscopy: an analysis of its efficacy, safety, and tolerability; Gastrointest Endosc, 72 (2010), pp. 406–412

- [9] C. Hassan, M. Bretthauer, M.F. Kaminski, M. Polkowski, B. Rembacken, B. Saunders, et al.; Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline; Endoscopy, 45 (2013), pp. 142–150

- [10] A.A. Siddiqui, K. Yang, S.J. Spechler, B. Cryer, R. Davila, D. Cipher, et al.; Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality; Gastrointest Endosc, 69 (2009), pp. 700–706

- [11] E.H. Seo, T.O. Kim, M.J. Park, H.R. Joo, N.Y. Heo, J. Park, et al.; Optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy interval in split-dose PEG bowel preparation determines satisfactory bowel preparation quality: an observational prospective study; Gastrointest Endosc, 75 (2012), pp. 583–590

- [12] B. Lebwohl, F. Kastrinos, M. Glick, A.J. Rosenbaum, T. Wang, A.I. Neugut; The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy; Gastrointest Endosc, 73 (2011), pp. 1207–1214

- [13] C.A. Aronchick, W.H. Lipshutz, S.H. Wright, F. Dufrayne, G. Bergman; A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda; Gastrointest Endosc, 52 (2000), pp. 346–352

- [14] R.L. Barclay, J.J. Vicari, A.S. Doughty, J.F. Johanson, R.L. Greenlaw; Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy; N Engl J Med, 355 (2006), pp. 2533–2541

- [15] N.N. Baxter, R. Sutradhar, S.S. Forbes, L.F. Paszat, R. Saskin, L. Rabeneck; Analysis of administrative data finds endoscopist quality measures associated with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer; Gastroenterology, 140 (2011), pp. 65–72

- [16] H. Pohl, A. Srivastava, S.P. Bensen, P. Anderson, R.I. Rothstein, S.R. Gordon, et al.; Incomplete polyp resection during colonoscopy-results of the complete adenoma resection (CARE) study; Gastroenterology, 144 (2013), pp. 74–80 e1

- [17] M. Khashab, E. Eid, M. Rusche, D.K. Rex; Incidence and predictors of “late” recurrences after endoscopic piecemeal resection of large sessile adenomas; Gastrointest Endosc, 70 (2009), pp. 344–349

- [18] F. Froehlich, V. Wietlisbach, J.J. Gonvers, B. Burnand, J.P. Vader; Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study; Gastrointest Endosc, 61 (2005), pp. 378–384

- [19] B. Rembacken, C. Hassan, J.F. Riemann, A. Chilton, M. Rutter, J.M. Dumonceau, et al.; Quality in screening colonoscopy: position statement of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE); Endoscopy, 44 (2012), pp. 957–968

- [20] J.M. Church; Effectiveness of polyethylene glycol antegrade gut lavage bowel preparation for colonoscopy—timing is the key!; Dis Colon Rectum, 41 (1998), pp. 1223–1225

- [21] D. Frommer; Cleansing ability and tolerance of three bowel preparations for colonoscopy; Dis Colon Rectum, 40 (1997), pp. 100–104

- [22] H.M. Chiu, J.T. Lin, Y.C. Lee, J.T. Liang, C.T. Shun, H.P. Wang, et al.; Different bowel preparation schedule leads to different diagnostic yield of proximal and nonpolypoid colorectal neoplasm at screening colonoscopy in average-risk population; Dis Colon Rectum, 54 (2011), pp. 1570–1577

- [23] B. Lebwohl, T.C. Wang, A.I. Neugut; Socioeconomic and other predictors of colonoscopy preparation quality; Digest Dis Sci, 55 (2010), pp. 2014–2020

- [24] T.D. Gohel, C.A. Burke, P. Lankaala, A. Podugu, R.P. Kiran, P.N. Thota, et al.; Polypectomy rate: a surrogate for adenoma detection rate varies by colon segment, gender, and endoscopist; Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 12 (2014), pp. 1137–1142

- [25] H.M. Chiu, H.P. Wang, Y.C. Lee, S.P. Huang, Y.P. Lai, C.T. Shun, et al.; A prospective study of the frequency and the topographical distribution of colon neoplasia in asymptomatic average-risk Chinese adults as determined by colonoscopic screening; Gastrointest Endosc, 61 (2005), pp. 547–553

- [26] K. Leung, P. Pinsky, A.O. Laiyemo, E. Lanza, A. Schatzkin, R.E. Schoen; Ongoing colorectal cancer risk despite surveillance colonoscopy: the Polyp Prevention Trial Continued Follow-up Study; Gastrointest Endosc, 71 (2010), pp. 111–117

- [27] J. Lakoff, L.F. Paszat, R. Saskin, L. Rabeneck; Risk of developing proximal versus distal colorectal cancer after a negative colonoscopy: a population-based study; Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 6 (2008), pp. 1117–1121 quiz 1064

- [28] H. Singh, D. Turner, L. Xue, L.E. Targownik, C.N. Bernstein; Risk of developing colorectal cancer following a negative colonoscopy examination: evidence for a 10-year interval between colonoscopies; JAMA, 295 (2006), pp. 2366–2373

- [29] A. Pabby, R.E. Schoen, J.L. Weissfeld, R. Burt, J.W. Kikendall, P. Lance, et al.; Analysis of colorectal cancer occurrence during surveillance colonoscopy in the dietary Polyp Prevention Trial; Gastrointest Endosc, 61 (2005), pp. 385–391

- [30] B. Leggett, V. Whitehall; Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis; Gastroenterology, 138 (2010), pp. 2088–2100

- [31] P. Schoenfeld, B. Cash, A. Flood, R. Dobhan, J. Eastone, W. Coyle, et al.; Colonoscopic screening of average-risk women for colorectal neoplasia; N Engl J Med, 352 (2005), pp. 2061–2068

- [32] E.C. Gonzalez, R.G. Roetzheim, J.M. Ferrante, R. Campbell; Predictors of proximal vs. distal colorectal cancers; Dis Colon Rectum, 44 (2001), pp. 251–258

- [33] G.S. Cooper, F. Xu, J.S. Barnholtz Sloan, M.D. Schluchter, S.M. Koroukian; Prevalence and predictors of interval colorectal cancers in Medicare beneficiaries; Cancer, 118 (2012), pp. 3044–3052

- [34] M. Okamoto, Y. Shiratori, Y. Yamaji, J. Kato, T. Ikenoue, G. Togo, et al.; Relationship between age and site of colorectal cancer based on colonoscopy findings; Gastrointest Endosc, 55 (2002), pp. 548–551

- [35] A.T. Chan, E.L. Giovannucci; Primary prevention of colorectal cancer; Gastroenterology, 138 (2010), pp. 2029–2043 e10

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?