(Created page with "==Abstract== This paper reviews the research, policy proposals and recommendations, implemented policies, and programs on sustainable transportation since 2000, with regional...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 859806558 to Zhou 2012a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 11:38, 12 May 2017

Abstract

This paper reviews the research, policy proposals and recommendations, implemented policies, and programs on sustainable transportation since 2000, with regional focus on the US, using the UK (related to the European Union if appropriate), and Canada as references. The paper finds that the concept of sustainable transportation has been given increased attention in all places. There are significant variances between the research, policy proposal, and implementation. Efforts made towards sustainable transportation, and the focus of the efforts at entities within and outside the US also vary notably. As a whole, the US did more research on sustainable transportation than the reference countries and it even undertook several studies of sustainable transportation practices in West Europe. The US federal government is less aggressive than its foreign counterparts in marketing and implementing sustainable transportation. This is evidenced by a lack of overarching federal policy (mandate) on and a universal working definition for sustainable transportation, and absence of a gateway and dedicated website to market and disseminate the idea of sustainable development in general and sustainable transportation in particular.

Keywords

Transportation ; Sustainability ; Research ; Policy ; Program

1. Introduction

Past literature on the sustainability issue in the US has focused more on local-level policies and initiatives than on federal-level ones. This might be due to many factors. For instance, there is a lack of governmental mandates for sustainability actions (Deakin, 2002 ), and there are (rightly so) more local sustainability initiatives and programs than federal ones (see Portney, 2002 ; Portney, 2003 ; Chifos, 2001 ; Chifos, 2007 ; Public Technology, Inc, 1996 ; Black and Sato, 2007 ).1 Regardless of the underlying causes, the relative paucity of literature on federal-level sustainability policy is a fact (Chifos, 2007 ). To effectively implement sustainable transportation policies, however, national (federal) governments are major driving forces that “bridge the gap between policy recommendations and their implementation” (European Conference of Ministers of Transport [ECMT], 2002, p. 3 ). Bearing this fact in mind, I undertake three tasks in this paper. The first task is to review existing definitions of sustainable transportation to identify the commonalities among them. Fulfilling this task would help us delimit, select, and prioritize any “sustainable transportation” research, policies, or programs. The second task is to review goals, visions, and strategies for sustainable transportation at the national level in the US and two reference countries according to the “commonalities” identified. Accomplishing this task somewhat help fill the gap in existing literature on sustainable transportation. The third task is to explore whether there are significant gaps among what have been researched, proposed, and adopted, by making comparisons between the US and the reference countries and between what was proposed and what was implemented. The purpose of this task is to provide guides about consolidating discrete efforts in sustainable transportation research, policy analysis, and implementation.

To facilitate efficient completion of these tasks I have limited the regional focus and time frame for the studies. The US is the primary focus, but special attention is also given to Canada, and the UK (sometimes expanded to the European Union [EU], when required). The Canadian and UK cases were selected as “reference countries” to engage the US scholarship and to help identify gaps in the sustainable transportation efforts undertaken in the US. Canada and the UK are more comparable to the US than most other developed countries, politically, culturally, and economically. Thus they should be good subjects for comparisons or good references, particularly when one wants to find transferrable knowledge for the US. Regarding time frame, literature and efforts after 2000 were accorded the most importance, as they reflect the most recent trends or practices and would represent some of the most valuable knowledge and experiences about sustainable transportation.

This paper is organized into five sections. Section 2 discusses the genesis of “sustainable transportation” and how “sustainable transportation” has been defined. The discussion provides some common ground for ensuing summaries of existing goals, visions, and strategies about sustainable transportation. Section 3 reviews existing goals, visions and strategies about sustainable transportation by individuals. It is assumed that since individual research and proposals are often not bounded by as many political constraints facing government agencies or other entities, individuals should be able to think more boldly. Thus they should have advanced the most innovative and comprehensive ideas about sustainable transportation. Section 4 reviews goals, visions, and strategies proposed by high-profile entities, including NGOs, international banks, think tanks, intergovernmental organizations, national governments, and governmental agencies. It is argued that what was prescribed by these entities is generally closer to actions than those by individuals or is actual implementation of ideas about sustainable transportation. Section 5 discusses potential gaps in sustainable transportation efforts undertaken in the US. Section 6 concludes the paper, presenting the overall findings and discussing future research directions.

2. Defining sustainable transportation

An important task of sustainable transportation research and policy is reaching an agreed-upon definition of “sustainable transportation”. Without such a definition, we simply do not know where to start, let alone to persuade others into pursuing sustainable transportation. Specifically, if decision-makers do not know clearly what they mean by “sustainable transportation”, it is almost impossible for them to promote it, as it will be a moving target and policies and programs based on it would not be consistent and decisive.

About 15 years ago, OECD (1996) commented that there had been extensive research on defining and setting conditions for sustainable development but comparatively little on sustainable transportation. With respect to “sustainable development”, the most influential definition is probably the one given in The Brundtland Report—Our Common Future , a publication by the World Commission on Environment and Development of the United Nations. In this report, sustainable development is defined as development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs” ( The World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987 ). Many entities have simply adopted the above sustainable development definition as theirs, as indicated in Sustainable Development Commission (2011) , Black (2005) , and Transport Canada (1997) . In academia, voluminous research has been done on how sustainable development is constituted and how to approach it, for instance, Eichler (1995) , Benton (1996) , Castro (2004) , and Rogers et al. (2008) all provide a review of existing research and efforts, using different ways to categorize a large body of materials they identified.

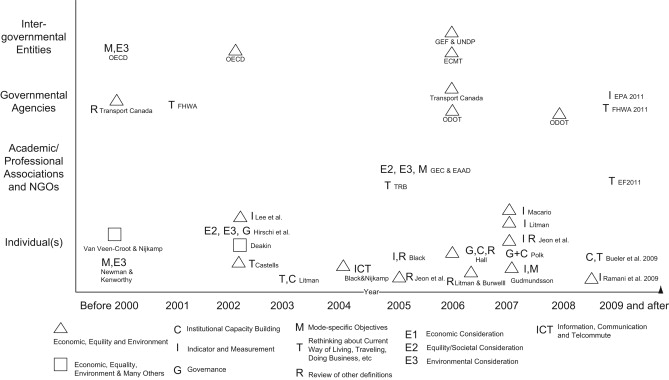

Partially built on the research on sustainable development, the past 10 years or so have seen several reviews of different definitions of sustainable transportation (e.g., Black, 2005 ; Hall, 2006 ; Litman and Burwell, 2006 ; Jeon et al ., 2007 ; Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), 2011 ; Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), 2006 ; ODOT, 2008 ). In each of the reviews, authors were able to identify many definitions of “sustainable transportation”. The lack of discussion on definitions of “sustainable transportation” argued by OECD (1996) thus now is no longer the case. To substantiate, Fig. 1 highlights some sustainable transportation definitions since 2000.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Selected work on defining and indicating “sustainable transportation”. (US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2011) ; FHWA (2001) ; GEF and United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (2006) ; General Exhibitions Corporation (GEC) and the Environmental Agency in Abu Dhabi (EAAD) (2005) ; Hirschi et al. (2002) ; Newman and Kenworthy (1999) ; Polk (2007) ; Ramani et al. (2009) . |

Most authors believe that “sustainable transportation” is derived from the idea of sustainable development (OECD, 1996 ; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2002 ; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2002 ; Hall, 2002 ; Hall, 2006 ). In its totality, sustainable transportation has three equally-weighted considerations: environment, economy, and equity (society) (e.g., Litman and Burwell, 2006 ; Hall, 2006 ; Deakin, 2002 ; Lee et al ., 2002 ). This argument is consistent with those by governmental or intergovernmental entities such as Transport Canada (1997) and ECMT (2002) . “Although there is no single, commonly held definition of sustainable transportation, for the department the concept means that the transportation system, and transportation activity in general, must be sustainable on three counts—economic, environmental and social” (Transport Canada, 1997 ). To ECMT, “sustainable urban travel” is providing mobility with little or no harmful impact on health and environment and is providing mobility that ensures economic prosperity at no danger of depleting limited natural resources.

In discussing sustainable transportation, the early focus has been on environmental degradation caused by automobile and resource depletion as a result of petroleum usage (Deakin, 2002 ; Black and Sato, 2007 ). In recent years, authors have gone beyond the focus and have attempted to define and to approach sustainable transportation in more dimensions. These dimensions include: seeking an “integrated solution” to sustainable transportation (Litman and Burwell, 2006 ), building institutional capacity and reforming existing institutions (Hall, 2006 ), benchmarking transportation sustainability (Black, 2005 ), operationalizing the definition of sustainable transportation at the regional level (Jeon et al., 2007 ) and integrate sustainability into routine transportation planning processes at the local and state levels (FHWA, 2011 ).

Arguing that sustainable transportation has both a “narrow definition” and a “broader definition”, Litman and Burwell (2006) contend that the latter enables people to think more comprehensively about all the impacts of transportation. Narrowly defined sustainable transportation focuses on resource depletion and air pollution, while broadly defined sustainable transportation considers not only the aforementioned but also “economic and social welfare, equity, human health and ecological integrity”. The latter facilitates people to search for “opportunities for coordinated solutions”, which encompass “improved travel choices”, “economic incentives”, “institutional reforms”, and “technological innovation”. It would also contribute to an “integrated solution” to sustainable transportation.

Built on OECD (1996) , Hall (2002) , Litman and Burwell (2006) , Victoria Transport Policy Institute (VTPI) (2005) , and Hall (2006) argues that sustainable transportation needs to look at these elements: environment, economy, equity, and governance. He contends that the most existing definitions of sustainable transportation are lack of “system-/sector-centric views that tend to be less cognizant of the wider issues (p. 478)”. He advocates a comprehensive definition for sustainable transportation which “include[s] the transportation sectors interconnections with other sectors” (p. 478). This definition would help address the lack of an integrated approach to decision-making within the US federal system, which is a major obstacle to progress towards sustainable development and sustainable transportation (Hall and Sussman, 2007 ).

Commissioned by the Transportation Research Board (2005) and Black (2005) conducts a systematic review of existing definitions on sustainable transportation. He argues that there are multiple ways to define and indicate sustainable transportation but all the ways are “moving toward measurement at some point (p. 37)”. Sustainable transportation should consider measurement of these phenomena related to, or impacts of the transportation sector:

- Diminishing petroleum reserves;

- Global atmospheric impacts;

- Fatalities and injuries;

- Local air quality impacts;

- Congestion;

- Noise;

- Biological impacts;

- Equality.

In the same vein, Black and Sato (2007) argue that sustainable transportation results from peoples widespread concern over global warming, which is a component in the sustainable development (Deakin, 2002 ). According to Black and Sato (2007) , sustainable transportation could be best defined by the factors that make transport unsustainable and by what can be done about such “negative externalities” of transportation.

Interested in measuring sustainable transportation and the progresses made in Atlanta, GA, Jeon and Amekudzi (2005) and Jeon et al. (2007) explore working definitions of sustainable transportation used by different government agencies, professional, and academic entities. Their work indicates that multiple governmental agencies, academic/professional entities, NGOs, and international organizations had been pursuing “sustainable transportation”, no matter they had defined sustainable transportation or not at the outset. The US Department of Transportation (USDOT) and 14 State DOTs had listed the sustainability-related objectives in their respective mission statements as of 2007. Despite this, many of them did not even define what “sustainable transportation”. Outside the US, according to Jeon and Amekudzi (2005) and Jeon et al. (2007) , institutions in Canada, for instance, VTPI and the Center for Sustainable Transportation (CST) had working definitions for sustainable transportation in place since 2003 and 2005, respectively. VTPIs definition emphasizes social and equity aspects of transportation systems “attentive to basic human needs”. CSTs definition encompasses economic, environmental, and social aspects of transportation. Per the CST definition, sustainable transportation should account for multiple objectives simultaneously: access needs of individuals, safety, transportation system operation efficiency, environmental protection, and economic vitality.

Putting all the above work on defining “sustainable transportation” together, we can see that there is still not a universally accepted definition of “sustainable transportation”. Collectively, the definitions identified still show that

- The idea of “sustainable transportation” derives from the concept of sustainable development.

- Sustainable transportation is about a balanced pursuit of multiple objectives. At the minimum, sustainable transportation should equally account for the transportation sectors impacts on local society, economy, and the environment.

- To better define or pursue sustainable transportation, it is necessary to somehow measure how “sustainable” or “unsustainable” existing or planned transportation systems are. This also means that when pursuing sustainable transportation, there should be a task about establishing a measurement or accounting system for transportation.

- Sustainable transportation is not just about how a transportation system performs or is measured. It is also about institutional capacity building, institutional reform, governance, interconnections between the transportation sector and other sectors, among others.

- Lack of a working definition of “sustainable transportation does not prevent people from promoting “sustainable transportation”.

Bearing the above findings in mind, the following discussion on goals, visions, and strategies of sustainable transportation adopt a broad rather than narrow perspective. This allows us to look at various goals, visions, and strategies directly or indirectly related to “broadly defined” rather than “narrowly defined” sustainable transportation, which “dominates nearly all research in transport” (Black and Sato, 2007 ).

3. Goals, visions, and strategies by individuals

No matter how they defined “sustainable transportation”, individuals and entities have proposed different goals, visions and strategies of “sustainable transportation”. At some risk of oversimplifying, I have summarized existing goals, visions and strategies by individuals into the following groups, according to: what people think sustainable transportation is all about, how they trace the root of sustainable transportation, and how they think sustainable transportation ideas can be materialized.

3.1. Sustainable transportation is about measurement

If one does not know how sustainable or unsustainable the current transportation system is, she or he probably does not know exactly what to do next about the system (Black, 2005 ). Table 2 summarizes the indicators and measurements for “sustainable transportation” proposed by different authors. On the one hand, the indicators and measurements quantify impacts of different transportation systems; on the other hand, they partially represented the directions where the authors want “sustainable transportation” to go, and which areas “sustainable transportation” strategies/goals should focus on.

3.2. Sustainable transportation is about changes

With a thought that “sustainable development is the code word for the most important social debate of our time”, Castells (2002) questions the current ways of consumption and transportation. He argues that sustainable development and sustainable transportation are both about changes in general and about changes in large cities in particular—“it is in large cities where we generate most of the CO2 emissions that attack the ozone layers” and “[it] is our urban model of consumption and transportation that constitutes the main cause of the process of global warming and can irreversibly damage the condition of livelihood”. Similarly, Litman (2003) asks for “rethinking” about the end, focus, and decision-making process in transportation planning—“sustainability requires rethinking how we measure transportation”. Vehicle movement should not be “an end in itself” and transportation planners should consider “access” and “comprehensive decision-making”. To him, better planned “access” reduces the needs for travel while not compromising quality of life. “Comprehensive decision-making” requires people look at both “direct” and “indirect” impacts of transportation.

3.3. Sustainable transportation as a part of sustainable development

Deakin (2002) argues that sustainable development is an outcome of peoples increased concerns about environmental quality, social equally, economic vitality, and the threat of global climate change. The strategies for increasing transportation sustainability, a “principal component” of sustainable development, include demand management, operation management, pricing policies, vehicle technologies, clean fuels, and integrated land use and transportation planning (pp. 5–6). In the same vein, Benfield and Replogle (2002) maintained that sustainable transportation is an essential component of sustainable development as transportation is a “prerequisite to development in general” and “contributes substantially to a wide range of environmental problems, including energy waste, global warming, degradation of air and water, noise, ecosystem loss and fragmentation, and decentralization of landscape”. They point out that “legal and political framework for sustainability in American transportation has been improved” since 1992 but the US federal government had not addressed “matters related to fuel efficiency and emissions control through vehicle technology”. Their proposed federal-level strategies for sustainable transportation are:

- Establish and work towards goals for energy conservation and equity;

- Recognize “induced demand” in transportation planning and management;

- Provide subsidy for less polluting transportation modes;

- Encourage use-based car insurance;

- Improve and expand pedestrian and bicycle facilities;

- Expand incentives for affordable housing near jobs and transit;

- Improve motor vehicle fuel economy with stronger CAFE standards.

3.4. Sustainable transportation is beyond transportation

Instead of focusing on specific strategies or visions for sustainable transportation, Hall (2006) focuses on a decision-support framework and a “road map for developing policy that will move the transportation system towards sustainability”. Hall argues that sustainable transportation is not just about the transportation sector, and that there is a lack of integrated decision-making mechanism for promoting sustainable development within the US federal political system. According to him, federal agencies, especially USDOT should be “enlightened” and lead efforts towards sustainable transportation. Hall identifies major challenges faced by the US for promoting sustainable transportation as the “problems of horizontal, vertical, spatial, and temporal integration”. He asserts that in the current political setting, USDOT is relatively weak given the “division of transportation functions across Congressional committees, powerful policy networks that promote modal interests without necessarily being concerned about the wider system impacts (p. 667)”. In addition, despite there were “a number of federal initiatives that support the progress of specific aspects of sustainable transportation”, “the effectiveness of these initiatives is likely to be reduced by the fact that there is no federal mechanism to coordinate or integrate these activities (p. 687)”. Thus, Hall (2006) recommends that different elements (i.e., economic, social, and environmental objectives) of sustainable transportation be pursued separately. “Given the lack of Congressional interest in sustainable development, a better approach than pushing the ST (Sustainable Transportation) framework in a unified manner might be to repackage and promote the various elements of the framework individually (p. 631)”.

4. Goals, visions, and strategies by high-profile entities

Since the publication of Our Common Future in 1987, the concept of sustainable development has been increasingly accepted by NGOs, governmental and intergovernmental agencies, professional associations, academic organizations, among others. As an important element of the concept, sustainable transportation has also been increasingly attended to. Many high-profile entities have articulated their specific visions, goals, and strategies for sustainable transportation. Unlike what was discussed in academia, opinions or positions explicitly expressed by these entities that are closer to public policies and actions. The following subsections discuss the visions, goals, and/or strategies for sustainable transportation by these entities.

4.1. Entities with a global perspective

Other than the United Nations, the World Bank is another influential entity which has a global presence and which is interested in promoting sustainability. The World Bank started addressing the issue of sustainable transportation in its publication in 1996. It argued that then there were three challenges facing the transportation sector in different countries:

- Increasing responsiveness to customer needs;

- Adjusting to global trade patterns;

- Coping with rapid motorization.

To cope with these challenges, it recommends nations reform transportation policy, incorporating the idea of “sustainability”. It interprets “sustainability” as a three-fold concept: economic and financial sustainability, environmental and ecological sustainability, and social sustainability. Economic and financial sustainability means that “resources be used efficiently and that assets be maintained properly”. Environmental and ecological sustainability indicates that “the external effects of transport be taken into account fully when public or private decisions are made that determine future development”. Social sustainability requires that “the benefits of improved transport reach all sections of the community” (World Bank, 1996 ). The above concept has long standing impacts on how other entities define sustainable transportation and deal with related issues. For instance, in a background paper prepared for the World Resources Institute (WRI), Lagan and McKenzie (2004) recommend that the WRI refer to the concept. In 2011, a sustainable transportation guidebook by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) (FHWA, 2011 ) also adopts the above concept.

As a global environmental think tank, in 2002, the WRI also established EMBARQ, the WRI Center for Sustainable Transport, which “fosters government-business-civil society partnerships whose members are committed to finding solutions to the transportation-related problems in their cities (EMBARQ, 2012 )”. Similar to EMBARQ, several other NGOs with an international presence have worked on transportation system sustainability across nations. Most of these entities do not have an explicit definition of “sustainable transportation” but are very active in areas such Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), clean fuel, green freight trucks, and urban design. Good examples of these entities are the Institute of Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), The Energy Foundation (EF), and Clean Air Initiative for Asian Cities (CAI-AC). More specifically, ITDP helped deliver the Guangzhou BRT project. Working with Calthorpe Associates, EF published a guide for low-carbon neighborhood design. In this document, innovative street design is used to promote transit and non-motorized modes of transportation (The Energy Foundation, 2011 ). CAI-AC has completed several “green trucks” projects in Guangzhou and Manila.

In recent years, Brookings, an influential think tank in the US has also shown an interest in sustainable transportation. In 2009, it sponsored a report on Germanys sustainable transportation experience. In this report, the authors argue that density and income do not explain the differences in car dependence in the US and in Germany. They recommend the following strategies for the US based what Germany did and achieve in sustainable transportation:

- Using pricing to encourage the use of less polluting cars, driving at non-peak hours and more use of public transit;

- Fully coordinate and integrate transportation-land use planning;

- Increase public awareness of sustainability;

- Implement policies in stages with a long term perspective (Buehler et al., 2009 ).

4.2. Entities in Europe

ECMT is one of the first intergovernmental organizations that articulated policy tools for “sustainable urban travel”, an alternative name for sustainable transportation (Black, 2005 ). As early as 1995, the ECMT released a report titled “Urban Travel and Sustainable Development”. In this report, the ECMT emphasizes the following policy tools:

- Economic incentives and disincentives;

- Land-use planning;

- Traffic management schemes;

- Marketing, telematics and other innovations to improve public transport.

In 2000, the ECMT further elaborated the above tools to cover the following sustainable transportation policy goals:

- Improved decision making incorporating best practice in cost benefit analysis and environmental assessment;

- Efficient and coherent pricing and financing of infrastructure;

- Reducing CO2 emissions from road transport;

- Promoting the use of low emission trucks;

- Improving the competitiveness of road alternatives – rail and inland shipping – and removing barriers to international development of their markets;

- Improving road safety;

- Resolving conflicts between transport and sustainable development in urban environments (ECMT, 2000 )

In another document focusing on urban transportation sustainability, ECMT (2002, p. 12) believe that cities could reduce car travel to “achieve sustainable urban development”. For member national governments pursuing sustainable transportation, ECMTs recommended strategies are:

- Establish supportive national policy frameworks;

- Improve institutional co-ordination and co-operation;

- Encourage effective public participation, partnerships and communication;

- Provide a supportive legal and regulatory framework;

- Ensure a comprehensive pricing and fiscal structure;

- Rationalize financing and investment stream;

- Improve data collection, monitoring and research.

In 2003, the European Council of Town Planners (ECTP) released The New Charter of Athens 2003 , which details ECTP members’ shared visions on the future of European cities. In the document, ECTP emphasizes that European cities of future should provide their citizens with “a varied choice of transportation modes” and “accessible and responsible information networks”. ECTP points out that sustainable transportation should cover the movement of “persons”, “materials”, as well as “information flows”. At different “scales”, ECTP puts forward different strategies and goals for sustainable transportation. At the strategic scale, ECTP treats sustainability as one of the four goals for the future EU transportation network. 2 At the city level, ECTP regards “ease of movement and access” and “greater choice in the mode of transportation” as “critical element[s] of city living”. Within the city transportation network, ECTP attaches great importance to interchange facilities and separation of residences and rapid transportation networks. At the travel demand management scale, ECTP advocates for “full integration of transportation and town planning”, “imaginative urban design”, and “easier information access” (ECTP, 2003 ).

In the UK, one of the most notable steps towards sustainable transportation is on-line information sharing and marketing. To increase public awareness of the UKs sustainable development strategy, for instance, the UK government launched a gateway website in 2005 (The Sustainable Development Unit, 2007 ). This website is not specifically dedicated to sustainable transportation, however, transportation was mentioned as a component of “sustainable communities”, one the four key priority areas in the UKs sustainable development strategy.3 Per the strategy, a sustainable community should be “well connected—with good transport services and communication linking people to jobs, schools, health and other services”. The strategy also lays out 68 indicators to evaluate the sustainability at the national level. Of these indicators, many are transportation-related, such as GHG emissions, road transport connectivity and efficiency, accessibility, and road accidents.4

The UK Department for Transport (DfT), following the UK governments footstep, has published a series of on-line reports covering in-depth the following topics that are related to sustainable transportation:

- Alternatives to travel: how employees can reduce trips while do not compromise productivities;

- How GHG emissions can be measured and reported according to the Dft requirements (DfT, 2011a );

- Information about biofules (DfT, 2011b );

- How to consider sustainable transportation in new development (DfT, 2008 );

- How 15 local governments in the UK had simultaneously addressed the sustainable transportation and housing growth issues (DfT, 2010 );

- How different individuals can use travel plans to make more green trips (DfT, 2011c );

- Guides for local governments about how to deliver sustainable, low carbon, travel (DfT, 2009 ).

4.3. Canadian Entities

In Canada, Transport Canada, whose US equivalent is the USDOT, developed probably one of the most comprehensive websites on sustainable transportation by a government agency as of 2009. The website defines what “sustainable transportation” is, explains how sustainable development is related to sustainable transportation, and articulates Transport Canadas strategies to cope with sustainable transportation. Transport Canada (2007) thinks that a sustainable transportation system should be “safe, efficient and environmentally friendly”. To turn such a system into reality, it requires integration of “economic, social and environmental considerations” into transportation policy-making. Per Transport Canada, it is challenging to “balance” the above considerations but there were always “win–win–win opportunities”. In terms of the relationship between sustainable development and sustainable transportation, Transport Canada regards the latter as natural derivative of former, while Our Common Future laid out the theoretical foundation for both.

At the strategy and action plan levels, Transport Canada has published four editions of “Transport Canadas Sustainable Development Strategies” since 1997, to help integrate sustainability into transportation policymaking process. These documents address specific sustainable transportation challenges facing Canada and strategies that Transport Canada should adopt to overcome the challenges. In the most recent version of the documents, Transport Canada (2006) indicates that Canada was faced by the following challenges and its commitments would focus on the challenges “to influence in order to promote a sustainable transportation system”:

- Encourage Canadians to make more sustainable transportation choices;

- Enhance innovation and skills development;

- Increase system efficiency and optimize modal choices;

- Enhance efficiency of vehicles, fuels and fueling infrastructure;

- Improve performance of carriers and operators;

- Improve decision-making by governments and the transportation sector;

- Improve management of Transport Canada operations and lands.

Besides Transport Canada, many other Canadian federal departments are also required to prepare their respective sustainable development strategies every three years.5 Ad-hoc committees are also organized to review these strategies to ensure that they are coordinated. The above efforts indicate that the Canadian federal government has realized the importance to adopt a comprehensive and coordinated approach to achieving sustainability.

Outside the government, VTPI has been another active non-governmental entity which has generated quite a few documents on sustainable transportation. Notably, the following topics have been covered by in VTPIs publications on the following topics are available on-line freely to the general public:

- How to define sustainability and its goals, objectives and performance indicators;

- Paradigm shift needed to reconciled transportation and sustainability objectives;

- Indicators that can be used in sustainable transportation planning;

- How to reduce emissions from the transportation sector;

- How to evaluate transportation land use impacts;

- How to consider equity in transportation.6

4.4. Entities in the US

4.4.1. Advisory entities

In the US, TRB leads the nations brainstorming of sustainable transportation. By default, TRB is not a government agency and is only an entity that is to “promote innovation and progress in transportation through research. In an objective and interdisciplinary setting, TRB facilitates the sharing of information on transportation practice and policy by researchers and practitioners; stimulates research and offers research management services that promote technical excellence; provide expert advice on transportation policy and programs; and disseminates research results broadly and encouraged their implementation (TRB, 2012 )”.

In 2003, a Sustainable Transportation Symposium was held in the TRBs annual meeting in Washington D.C. Experts were invited to present their ideas about sustainable transportation theories and practices at various scales.7 A year later, TRB organized another meeting on sustainable transportation in the US. In the subsequent publication, 70+ participating experts provide their shared vision of sustainable transportation. Along the original concept of “sustainable development”, this vision highlights that “a sustainable transportation system is one that meets the transportation and other needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” (TRB, 2005, p. 3 ). Regarding the characteristics of a sustainable transportation system, the vision emphasizes:

- The role of transportation planners;

- The nurturance of sustainable transportation culture;

- Provision of transportation funding;

- Accountability;

- Feedback loop of planning activities;

- The role of flexibility and innovation in the transportation system.

The authors argue that transportation planners and providers should realize that there are multiple goals when sustainability comes into the field of transportation and they have to “struggle with” the trade-offs among those goals. Sustainable transportation culture is one that “not only sees sustainability as desirable but also accepts the inclusion of sustainability concepts (p. 3)”. “Adequate and reliable transportation funding consistent with fiscal constraints” is a necessity to promote the sustainable transportation culture (p. 3). Learning from the past and from real-time feedback of ongoing planning processes would enable people to make informed and better decisions about sustainable transportation.

After the above warming-up conferences, TRB has recently started working on indicators for sustainable transportation planning. In 2007 and 2008, two papers on such indicators were published by an individual who had participated in the TRB-sponsored efforts to develop the indicators (Litman, 2007 ; Litman, 2008 ).

At a much higher advisory position for the US government than TRB, the US National Academies (USNA) has embedded sustainable transportation into a much wider picture of sustainable development rather than treating the topic in-depth separately. In its projects since 2003, USNA has focused on general topics such as using scientific knowledge in policy and program decisions in developing countries, urban environmental sustainability in the developing world, pollution prevention and abatement handbook, biofuels, and ecosystem services. Sustainable transportation, if ever mentioned, was mostly considered as a subtopic within a broader backdrop of general sustainability within an international context.

4.4.2. Governmental entities

4.4.2.1. Federal-level

Unlike its counterparts in the UK and Canada, the US federal government did not have a gateway website for sustainable development or sustainable transportation as of 2011.8 Climate change, an important topic related to sustainable development or transportation; however, has garnered increased attention since about the 1990s (Black and Sato, 2007 ). For instance, there have been the US Climate Change Science/Technology Programs under the Office of President, White House, since 2002. If there were any specific federal-level visions, mission statements, or organizational goals about sustainable development and/or sustainable transportation, they are scattered across websites and/or documents of different agencies or their branches. Using key words such as “sustainability”, “clean air”, “climate change”, and “biofuels” to search across different federal agencies’ official websites, the author was able to identify sustainability-related goals or mission statements of four agencies. The author also found four five-year (2006–2011) strategic plans of these agencies. These plans were mandated by the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993.

EPA: In the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Strategic Plan, five long-term goals are proposed:

- Goal 1: Clean air and global climate change;

- Goal 2: Clean and safe water;

- Goal 3: Land preservation and restoration;

- Goal 4: Healthy communities and ecosystems;

- Goal 5: Compliance and environmental stewardship.

Relative to the notion of “sustainable transportation” as defined by individual authors mentioned above, Goals 1, 3, 4 and 5 are directly related to sustainable transportation. EPA has also set up some sub-objectives under these goals for the transportation sector. EPA emphasizes that reduction of emissions from the transportation sector should be a sub-objective. To achieve this sub-objective, EPA regards vehicle fuel-efficiency, alternative fuel, innovative technology, and international collaboration as major strategies (US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2007) ).

USDOT: In the strategic plan of USDOT, sustainability is only implicitly mentioned. USDOT puts forward six goals in the plan: safety, reduced congestion, environmental stewardship, security, preparedness and response, and organizational excellence (USDOT, 2006 ). The word “sustainability” is not explicitly used in any of the goals. However, if one uses the definitions sustainable transportation mentioned above, one can still find that some elements of sustainable transportation in the plan, for instance, safety, decreased accidents, reduction of GHG emissions, and environmental protection. Partially encouraged by this fact, some branches of USDOT have undertaken more explicit efforts towards transportation sustainability. In 2011, for instance, FHWA (2011) published a report titled “Transportation Planning for Sustainability Guidebook” for agencies working on sustainable transportation planning. This report reviews existing definitions of sustainable transportation. It also discusses how sustainability issues are addressed in different processes or subareas of transportation planning:

- Strategic planning;

- Fiscally-constraint planning;

- Performance measurement and performance-based planning;

- Climate change and transportation;

- Freight planning;

- Social sustainability in transportation.

In addition, the report summarizes domestic as well as international practices in sustainable transportation planning. In 2001, FHWA once sent a delegation to West Europe to study the sustainable transportation there. The delegation summarizes its findings as:

- Many sustainable transportation strategies and measures being implemented in West Europe had also been implemented in the US;

- The implementation saw different consequences in West Europe and in the US;

- The above differences caused by: (a) West Europe had started integrating sustainability into the planning process while the US was still focusing on mitigating the negative impacts of transportation; (b) Transportation agencies in West Europe had been given more authority over sustainability.

HUD: Similar to USDOT, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) also implicitly covers sustainability in its strategic plan. Of the six goals in the HUD plan, the words of “sustainability” or “sustainable” are rarely used. Only Goal C, “Strengthen Communities,” calls for sustainability: “enhance sustainability of communities by expanding economic opportunities” (HUD, 2006 ). Thus, despite the fact that HUD is the lead agency at the federal level responsible for urban development, urban sustainability, and related elements such as sustainable urban transportation and land use are not explicitly pursued in its strategic plan. This might indicate that, like the USDOTs pursuit of sustainability, HUD also faced barriers such as “uncertainties about the problem and the best ways to address it, uncertainties about public support, and lack of a clear mandate for action” (Deakin, 2002, p. 1 ). In addition, internal culture of sustainability may not be there yet as the plan was draft (cf, TRB, 2005 ).

Interdepartmental partnership: To better address sustainability issues across the administrative boundary, HUD, EPA and USDOT launched a joint program called “Partnership for Sustainable Communities (PfSC)” in 2009. The mission of the program is “to help improve access to affordable housing, more transportation options, and lower transportation costs while protecting the environment in communities nationwide. Through a set of guiding livability principles and a partnership agreement that will guide the agencies’ efforts, this partnership will coordinate federal housing, transportation, and other infrastructure investments to protect the environment, promote equitable development, and help to address the challenges of climate change The livability principles are:

- Provide more transportation choices : Develop safe, reliable, and economical transportation choices to decrease household transportation costs, reduce our nations dependence on foreign oil, improve air quality, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and promote public health.

- Promote equitable, affordable housing : Expand location- and energy-efficient housing choices for people of all ages, incomes, races, and ethnicities to increase mobility and lower the combined cost of housing and transportation.

- Enhance economic competitiveness : Improve economic competitiveness through reliable and timely access to employment centers, educational opportunities, services and other basic needs by workers, as well as expanded business access to markets.

- Support existing communities : Target federal funding toward existing communities—through strategies like transit oriented, mixed-use development, and land recycling—to increase community revitalization and the efficiency of public works investments and safeguard rural landscapes.

- Coordinate and leverage federal policies and investment : Align federal policies and funding to remove barriers to collaboration, leverage funding, and increase the accountability and effectiveness of all levels of government to plan for future growth, including making smart energy choices such as locally generated renewable energy.

- Value communities and neighborhoods : Enhance the unique characteristics of all communities by investing in healthy, safe, and walkable neighborhoods—rural, urban, or suburban ( EPA, 2011 ).

So in its mission statement or interpretation of “livability principles”, PfSC avoids using the word of “sustainability”. In the PfSC written agreement, there are not any performance measures or indicators to for the participating agencies to evaluate their respective progresses made towards livability (EPA, 2009 ).

DOE: Besides EPA, USDOT, and HUD, the US Department of Energy (DOE) has some interest in sustainable transportation as well. This interest is reflected in the DOEs aims specified in the programs it operated or sponsored. In its vehicle technologies program, for instance, DOE stresses that it is “developing more energy efficient and environmentally friendly highway transportation technologies…the long-term aim is to develop ‘leap frog’ technologies that will provide Americans with greater freedom of mobility and energy security, while lowering costs and reducing impacts on the environment” (DOE, 2007a ). At the city level, DOE has the Clean Cities program, which aims to “develop public/private partnerships to promote alternative fuels and advanced vehicles, fuel blends, fuel economy, hybrid vehicles, and idle reduction” (DOE, 2007b ).

In DOEs 2006–2011 strategic plan, sustainability is not specifically mentioned either. In the plan, “security” rather than “sustainability” is the code word. The plan describes DOEs vision as “to achieve results in our lifetime ensuring: Energy Security; Nuclear Security; Science-Driven Technology Revolutions; and One Department of Energy—Keeping our Commitments” (DOE, 2006 ). DOEs emphasis on sustainability is tied to economic development. For example, the DOE argues that taking actions specified in the plan ensure that “we are enhancing Americas energy security and sustaining our economic vitality (DOE, 2006 ).

4.4.2.2. State- and local levels

Compared to the US federal government, several states in the US are much more active in promoting sustainable transportation. The state-level sustainable transportation planning is not the focus of this paper. Interested readers can refer to FHWA (2011) , Oregon Department of Transportation (2008) , and Mineta Transportation Institute (2002) . They all contain a review of relevant efforts and documents. According to the above references, in addition to Washington D.C., there were five states in the US has a specific sustainable transportation plan and/or program in place: Oregon, Massachusetts, California, Washington, and Pennsylvania. At the local level, there have been more substantial efforts to link sustainability to transportation planning processes (e.g., Lee et al ., 2002 ; Jeon et al ., 2007 ; Portney, 2002 ; Portney, 2003 ).

In addition to the above, two state-level legislations in California are notable: AB 32 and SB 375. AB 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 sets the 2020 GHG emission reduction goal into Californias law. AB 375, Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act of 2008 enhances Californias ability to reach its AB 32 goals by promoting good planning with the goal of more sustainable communities. These two laws become precedents for the US. Despite both laws do not deal with transportation sustainability per sec, they do require significant reduction of GHG emissions from Californias transportation sector.

5. Gaps between research, proposals and programs

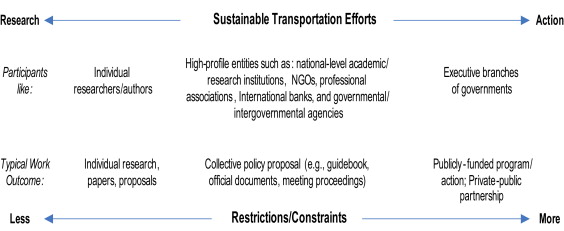

The foregoing section identifies and reviews existing efforts towards sustainable transportation. To better evaluate different efforts as a whole, there must be a way to synthesize them. Fig. 2 is the “taxonomy” used in this paper to complete the synthesis while Table 2 groups different efforts (especially proposed approaches to, and strategies for sustainable transportation) into a two-dimension table per the prescribed taxonomy. The taxonomy uses influence (ownership), status of participant, scope/content, and relation to research/action to classify different efforts.

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Taxonomy used to classify efforts towards sustainable transportation. |

In Table 2 , horizontally, depending on ownership, efforts are organized into three levels:

- Level 1: Research findings or proposals by individuals;

- Level 2: Policy proposals, recommendations, principles or proposed strategies by entities (including NGOs, international banks, think tanks, intergovernmental organizations, governmental agencies, among others);

- Level 3: programs and actions undertaken by governmental agencies.

Vertically, different strategies for, specific approaches to sustainable transportation are classified into 19 first-, 18 second-, and 6 third-level categories, respectively. Abbreviations in parentheses indicated ownership of research, proposals, or programs. All Level 1 and some Level 2 strategies were not differentiated by place as many of them are not place-specific. Visions and goals for sustainable transportation are not included in Table 2 since most of them are more or less reflected in the related strategies, as shown in Table 1 .

| Level 1: individual proposal | Level 2: entity proposal | Level 3: governmental agencies’ program/action | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Demand management | X (e.g., Deakin, 2002 ) | ||

| 2. Operation management | X (e.g., Deakin, 2002 ) | X (US) | |

| 3. Traffic management | X (US,UK) | ||

| 4. Pricing, subsidy, incentives, and disincentives | X (e.g., Deakin, 2002 ) | X (US,UK/EU) | |

| 4.1. Congestion fees | |||

| 4.2. Use-based insurance | X (US) | ||

| 4.3. Subsidy for “cleaner” modes | X (e.g., Lee et al., 2002 ) | X (US) | |

| 4.3.1. Bike and pedestrian facilities | X (e.g., Lee et al., 2002 ) | X (US) | |

| 4.3.2. Public transit | X (e.g., Lee et al., 2002 ) | X (UK) | |

| 4.4. Subsidy for TOD | |||

| 5. Technologies | |||

| 5.1. Fuels | X (e.g., Deakin, 2002 ) | X (US) | X (US) |

| 5.2. Vehicles | X (e.g., Deakin, 2002 ) | X (US) | X (US) |

| 5.3. Roads | |||

| 5.4. IT Technologies and communication | X (e.g., Black and Nijkamp, 2004 ) | X (UK/EU) | |

| 6. Institution | |||

| 6.1. Organization design and reform | X (e.g., Hall, 2006 ; Hall and Sussman, 2007 ) | ||

| 6.2. Legal/Policy framework | X (e.g., Benfield and Replogle, 2002 ) | X (CA,UK) | |

| 6.2.1. Fuel-economy requirements | X (e.g., Benfield and Replogle, 2002 ) | ||

| 6.2.2. Stronger vehicle emissions standards | X (e.g., Benfield and Replogle, 2002 ) | ||

| 6.3. Institutional co-ordination and co-operation | X (UK/EU) | X (US) | |

| 7. Planning and design | |||

| 7.1. Land use and transportation integration | X (e.g., Deakin, 2002 ) | X (US,UK/EU) | X (US) |

| 7.1.1. Jobs-housing balance | X (e.g., Lee et al., 2002 ) | ||

| 7.1.2. Induced demand in “transportation planning” | X (e.g., Lee et al., 2002 ) | ||

| 7.2. Urban design | X (e.g., Lee et al., 2002 ) | X (US, EU) | |

| 7.3. Access planning | X (e.g., Litman, 2003 ) | X (EU) | |

| 7.4. Accountability | X (US) | ||

| 7.5. Human resources | X (US) | ||

| 8. Finance and investment | X (e.g., Lee et al ., 2002 ; Jeon et al ., 2007 ) | X (UK/EU) | X (US) |

| 9. Marketing and promotion | X (UK/EU) | ||

| 10. Culture | X (US) | ||

| 11. Global perspectives | X (US) | X (US) | |

| 12. Information provision/dissemination | |||

| 12.1. Gateway websites/Dedicated websites | X (UK, CA) | X (UK,CA) | |

| 13. Data collection/analysis | X (UK/EU/US) | ||

| 14. Equality and society | X (e.g., Gudmundsson, 2007 ) | ||

| 15. Changes in thinking/behaviors | X (e.g.,Castells, 2002 ; Litman, 2003 ) | ||

| 16. Public participation | X (EU) | X (US)b | |

| 17. Safety | X (e.g., Black, 2005 ) | X (UK,CA) | X (US,UK,CA) |

| 18. Economic development | X (e.g., Litman and Burwell, 2006 ) | ||

| 18.1. Economic opportunities to promote community sustainability | X (US,UK,CA) | ||

| 19. Program evaluation | X (e.g., Jeon et al., 2007 ) | X (CA,UK) | |

| 19.1. Indicator development | X (see Table 2 ) | X (UK,CA,US) | X (UK) |

a. Abbreviations in parentheses: US: United States, UK: United Kingdom, EU: European Union or intergovernmental agencies within EU, and CA: Canada.

b. NEPA requires public involvement in environmental reviews and this could potentially be incorporated into sustainable transportation policy.

Of course, the synthesis in Table 2 is done at some risk of having some overlapping areas, as different strategies are not always mutually exclusive and there are multiple ways to differentiate and categorize them. Nevertheless, this synthesis provides an efficient and simple way to look at the sustainable transportation ideas that have been proposed and/or implemented.

| Author (Year) | Context/geographic area | Indicator/measurement | I/M reflected in proposed definition of, and strategies for sustainable transportation? | I/M adopted in practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Veen-Croot and Nijkamp (1998) | Posed policy proposal to the government based on the ‘factor four’ concept by Weizacuker et al. (1997) | Both negative and positive impacts of transportation (access, mobility, diversity of supply, cheaper goods/services, accidents, noise, air quality, visual intrusion/damage) | Partially | Not explicitly mentioned |

| Lee et al. (2002) | Reviewed California General Plan process can be utilize to promote local sustainable transportation system | Impacts of transportation on economy, environment, equity, and health | Yes | Vary from one local general plan to another, but many local plans have sustainable transportation policies. The linkage between transportation and land use is emphasized in the policy. |

| Transportation finance | ||||

| Use of auto/alternative modes of travel | ||||

| Need of travel | ||||

| Emission levels of different modes of travel | ||||

| Black and Nijkamp (2004) | Studied the trends in transportation, communication and mobility in Europe and US and highlighted the importance of the comparative and sustainability perspectives | Impacts of transportation on congestion, fatality, pollution, and landscape destruction; interdependence of information and communication technology and sustainable transportation. | Partially | Not explicitly mentioned |

| Gudmundsson (2007) | Reported on a project focusing on individual travel behavior and transport sustainability | Emissions, noise, safety, regional development, equality, accessibility | Partially | Emissions, safety, regional development, accessible, transportation system, energy saving, visual environment |

| Macario and Marques (2007) | Synthesized the urban mobility measures used in 19 European cities and studied their transferability | Transport information and management | Yes | Yes, I/M or their analogs were used in 19 European cities |

| Multimodal Interchanges | ||||

| Mobility Management | ||||

| Cycling | ||||

| Car Sharing and Car Pooling | ||||

| Zones with controlled access | ||||

| Clean vehicles and Fuels | ||||

| Public Transport | ||||

| Goods distribution and logistics services | ||||

| Parking management | ||||

| Road Urban Pricing | ||||

| Jeon et al. (2007) | Studied how local planning agencies can evaluate transportation system sustainability, using Atlanta as an example | Economic efficiency | Partially | A composite sustainability index was developed. The index was based on freeway speed, vehicle miles traveled per capita, emissions, vehicle hours travel per capita and exposure to emissions. |

| Economic development | ||||

| Financial affordability | ||||

| Social equality | ||||

| Safety | ||||

| Health | ||||

| Quality of life | ||||

| Natural resources | ||||

| System resilience | ||||

| Environmental integrity | ||||

| Black (2005) | Reviewed existing definitions of sustainable transportation and how the definitions affect related policy-making | Petroleum supply | Yes | Automobile emissions, biological effects, congestion, safety, and noise |

| Emissions | ||||

| Safety | ||||

| Congestion | ||||

| Noise | ||||

| Biological impact | ||||

| Equality | ||||

| DeLuchi et al. (2005) | Health | Partially | Not explicitly mentioned | |

| Climate change | ||||

| Energy | ||||

| Equality | ||||

| Land and community impact of transportation | ||||

| Impact of transportation on habitats and ecosystems |

Based on Table 2 , there are more Levels 1 and 2 proposals or strategies than what were implemented at Level 3. This echoes the conclusion made by ECMT (2002) : “Whilst the recommendations set out in Urban Travel and Sustainable Development have been well received, their implementation has proven easier said than done for a great number of cities and countries” (p. 3). The Levels 1 and 2 strategies/proposals that have been translated into Level 3 ones were often the least controversial ones, for instance, R&D of alternative fuels, innovations of vehicle technologies, and increasing sustainability through economic development. Complicated or subtle issues such as the nurturing of sustainable transportation culture, reforming current organizations to better promote sustainability, and pricing strategy still mostly stay at Levels 1 and 2. Some of the most promising progresses, however, are that attention has been given to:

- Benchmarking and evaluating transportation sustainability within the overall sustainability framework (e.g., The Sustainable Development Unit, 2007 );

- Guides about integrating sustainability in transportation planning (e.g., FHWA, 2011 );

- Interdepartmental collaboration on sustainability issues (e.g., PfSC);

- State-level efforts to promote some aspects of sustainable transportation (e.g., AB 32 and SB 375);

- One-stop website to get informed about sustainable development and sustainable transportation (e.g., The Sustainable Development Unit, the UK Government, 2007 ; Transport Canada, 2007 ).

In terms of Levels 2 and 3 proposals or programs/actions, significant variances exist between the US and the references. As a whole, the US seems to have more Level 2 proposals than the UK, EU, and Canada. However, only some of these had been actually translated into Level 3 programs or actions. Existing sustainable transportation related programs in the US have focused on these aspects: vehicle technologies, safety, international collaboration (assistance), and economic development. Unlike the UK and Canada, the US has not paid much attention to the evaluation of sustainability at the federal level. At the program/implementation level within the central/federal government, either UK or Canada have undertaken more actions on such issues as information dissemination, national-level legal and policy frameworks, and program evaluation.

Some of the above variances are gaps that need to be filled in the US’ federal-level efforts towards sustainable transportation, for instance, gateway websites, governmental initiatives, and indicators for general and transport sustainability. In the UK and in Canada, gateway websites have been established by governmental agencies to promote sustainable development and/or sustainable transportation. However, except the PfSCs website, author was not able to locate such websites by the US federal government as of 2011. Within the EU, ECMT as an intergovernmental organization has been very active in studying sustainable transportation and in making holistic policy recommendations to members’ national governments since the 1990s. Periodic checks of the implementation of the recommended also seem to be underway (e.g., ECMT, 2002 ). In Canada, similar efforts have been made within the federal government since 1997 as well. Many Canadian federal departments are even required by law to prepare a strategic plan on sustainable development every 3 years (The Canadian Government, 2004 ; The Canadian Government, 2007 ). In the US, research institutions and academic organizations have been very active in proposing policy recommendations for sustainable transportation but the federal government agencies have not done as much, for many reasons (Deakin, 2002 ; Hall, 2006 ; Black and Sato, 2007 ). Unlike Canada, there is no mandate for the US federal departments to prepare and update a strategic plan for department-specific sustainable development periodically. Probably due to this, the strategic plans by individual federal agencies such as USDOT, DOE, EPA, and HUD largely treat sustainability implicitly. This could also be due to the fact that the US federal government does not have an official working definition of overall sustainability. This is probably not a secret for most. Rockefeller Foundation, an entity is only marginally related to transportation issues, for instance, has criticized this lack at the US federal government like this: “In fact, the United States has no national transportation objectives. The federal government provides close to $50 billion a year for transportation infrastructure, but where that money goes is driven not by the societal outcomes it could achieve, but by the political benefit it delivers and by the need to satisfy state demands for perceived fair share. At every level of government where transportation decisions are made, too little attention is paid to return on investment or to maintaining the infrastructure we already have (Rockefeller Foundation, 2012 )”.

6. Conclusions

Despite there has been an increased amount of research on “sustainable transportation”, most individual authors, entities, and agencies still do not have an agreed-upon definition of “sustainable transportation”. This poses challenges to the review of existing literature and to the promotion of “sustainable transportation.” An inconsistent definition more or less means that we have a moving target in the collective effort towards “sustainable transportation.” However, this shortfall seems not to deter individuals, entities, and governmental agencies from engaging in the cause of “sustainable transportation”, as reflected in Table 1 ; Table 2 .

Adopting a broadly defined sustainable transportation concept based on synthesizing of selected definitions and classifying existing sustainable efforts with a prescribed taxonomy, this paper finds that sustainable transportation has garnered increased attention at all three levels: research, policy proposal, and program/implementation. However, there are still notable variances, and some of which are gaps to be filled as we muddle through the cause of sustainable transportation. This paper shows that there are significantly more Levels 1 and 2 proposals than Level 3 programs or actions. On the one hand, this reflects the fact that there is always a long way to go before most Levels 1 and 2 proposals are translated into Level 3 ones. On the other hand, there could be possibilities that:

- Most Levels 1 and 2 proposals are too generic to have substantive relevance to practices;

- Governmental agencies are not aware of the useful Levels 1 and 2 proposals;

- There are simply too many barriers for us to actually pursue sustainable transportation at the national level, no matter how.

The above possibilities open great room for further research, which could help bridge the gaps in and between different levels of research, proposals and/or actions. Some possible research questions for the future are:

- What is the relationship between different levels of research, proposals and/or actions?;

- How we could better inform governmental agencies of Levels 1 and 2 proposals?;

- What are some of the typical barriers for us to actually pursue sustainable transportation at the national, state and local levels?;

- How we can overcome the above barriers?.

Particularly, this paper finds that there are notable variances between the sustainable transportation efforts in the US, the UK, and Canada at the national level in the following aspects:

- Defining “sustainable transportation”;

- Disseminating information about sustainable transportation;

- Formulating overarching national sustainable transportation policy.

Compared to its UK and Canadian counterparts, the US federal government does not have an official definition of “sustainability”, does not have a mandate for departmental strategies/initiatives on sustainable development, and does not have a gateway website for marketing sustainability. But some entities and federal departments in the US have been quite active in pursuing sustainability and sustainable transportation. They even funded at least two in-depth studies of sustainable transportation practices in West Europe. A Canadian researcher was also involved in the development of sustainable transportation indicators sponsored by TRB. At the state and local levels, there have been many efforts to link sustainability to transportation planning processes. The above disconnect between the local/state and federal governments, nevertheless, begets the following research questions that the author can further work on:

- Which factors have prevented the US federal government from aggressively promote sustainable transportation as its UK and Canadian counterparts?

- Why some local and state governments in the US so actively pursue sustainable transportation despite there is a lack of federal policy on sustainable transportation?

- Would state- and local-level efforts towards sustainable transportation eventually give rise to the national sustainable transportation policy in the US?

- What are some of the lessons that other countries or regions can learn from the US, Canada and the UK experiences in sustainable transportation?

All in all, this paper is simply a baby step of our thousand-mile journey to sustainable transportation. It covers only a small portion of existing literature on sustainable transportation. It also uses a relatively simple research design. It only looks at what happens in the developed nations. But this baby step still shows that a periodic review of existing efforts towards sustainable transportation would generate new insights into the coordination and consolidation of the future efforts. In the long run, how much we can achieve in the cause of sustainable transportation may simply depend on how we learn from past experience of our own and relevant others.

References

- Benfield and Replogle, 2002 F.K. Benfield, M. Replogle; The roads more traveled: Sustainable transportation in America-or not; ELR News and Analysis, 6 (2002) Available at: 〈htpp://www.eli.org〉 (accessed 16.12.2006)

- Benton, 1996 T. Benton (Ed.), The Greening of Marxism, Guilford, London (1996)

- Black, 2005 Black, W.R., 2005. Sustainable Transport Definitions and Responses. In: Transportation Research Board. 2005. TRB Conference Proceedings 37: Integrating Sustainability into the Transportation Planning Process. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

- Black and Sato, 2007 W.R. Black, N. Sato; From global warming to sustainable transport 1989–2006; International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 1 (2007), pp. 73–89

- Black and Nijkamp, 2004 Black, W.R., P. Nijkamp, 2004. Transportation, Communication and Sustainability: In Search of a Pathway to Comparative Research. Available from: 〈ftp://zappa.ubvu.vu.nl/20040024.pdf〉 (accessed 4.06.2008).

- Buehler et al., 2009 R.J. Buehler, Pucher, U. Kunert; Making Transportation Sustainable: Insights from Germany; Brookings, Washington, D.C (2009)

- Castells, 2002 M. Castells; Preface; P.B. Evans (Ed.), Livable Cities?: Urban Struggles for Livelihood and Sustainability, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA (2002), pp. ix–xi 2002

- Castro, 2004 C. Castro; Sustainable development: Mainstream and critical perspectives; Organisation and Environment, 17 (2) (2004), pp. 195–226

- Chifos, 2001 Chifos, C., 2001. From Sustainable Development to Livable Cities: Changing Terms or Changing Focus? Implications for US urban policy. Presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Urban Affairs Association, Detroit, MI, April.

- Chifos, 2007 C. Chifos; The sustainable communities experiment in the United States: Insights from three federal-level initiatives; Journal of Planning Education and Research, 26 (2007), pp. 435–449

- Deakin, 2002 E. Deakin; Sustainable transportation: US dilemmas and European experiences; Transportation Research Record, 1792 (2002), pp. 1–11

- DeLuchi et al., 2005 DeLuchi, M., Ogden, J., Wang, M., Heanue, K.E., Johnston, B., Poorman, J.P., Nelson, A., Lookwood, S., Sanchez, T., Casgar, C., Schipper, L., Lee-Gosselin, M. Presentations on Transportation Sustainability Indicators. In: Transportation Research Board. 2005. TRB Conference Proceeding 37. Integrating Sustainability into the Transportation Planning Process. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

- Department for Transport (DfT), 2008 Department for Transport (DfT); Building Sustainable Transport into New Developments; DfT, UK, London (2008)

- DfT, 2009 DfT; Delivering Sustainable Low Carbon Travel: An Essential Guide for Local Authorities; DfT,UK, London (2009)

- DfT, 2010 DfT; Delivering Sustainable Transport Solutions for Housing Growth; (2010)

- DfT, 2011a DfT; Measuring and Reporting Greenhouse Gas Emissions-A DfT Guide to Work-related Travel; DfT,UK, London (2011)

- DfT, 2011b DfT, 2011b. Biofuels. Available from: 〈http://www2.dft.gov.uk/pgr/sustainable/biofuels/index.html〉 (accessed 02.01.2012).

- DfT, 2011c DfT, 2011c. Alternative to Travel. Available from: 〈http://www2.dft.gov.uk/pgr/sustainable/alternativestotravel.html〉 (accessed 02.01.2012).

- Eichler, 1995 M. Eichler; Change of Plans: Towards a Non-sexist, Sustainable City; Garamond, Toronto (1995)

- EMBARQ, 2012 EMBARQ, 2012. About EMBARQ. Available from: 〈http://www.embarq.org/en/about/about-embarq〉 (accessed 01.01.2012).

- EPA, 2009 EPA, 2009. HUD, DOT and EPA Partnership: Sustainable Communities. Available from: 〈http://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/pdf/dot-hud-epa-partnership-agreement.pdf〉 (accessed 02.01.2012)

- EPA, 2011 EPA, 2011. HUD, DOT and EPA Partnership for Sustainable Communities. Available from: 〈http://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/partnership/index.html〉 (accessed 02.01.2012)

- European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT), 2002 European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT); Implementing Sustainable Urban Travel Policies: Final Report; OECD Publications Services (2002)

- ECMT, 2000 ECMT; Sustainable Transport Policies; OECD Publications Services, Paris (2000)

- Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), 2011 Federal Highway Administration (FHWA); Transportation Planning for Sustainability Guidebook; FHWA, Washington, D.C (2011)

- FHWA, 2001 FHWA; Sustainable Transportation Practices in Europe; FHWA, Washington, D.C (2001)

- GEF and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2006 GEF and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2006. The GEF Small Grant Programme: Experiences and Lessons from Community Initiatives, New York. Available from: 〈http://www.undp.org/sgp/download/GEF_SGP_Sustainable_Transport_and_Climate_Change.pdf〉 (accessed 4.06.2008).

- General Exhibitions Corporation (GEC) and the Environmental Agency in Abu Dhabi (EAAD), 2005 General Exhibitions Corporation (GEC) and the Environmental Agency in Abu Dhabi (EAAD), 2005. International Conference on Sustainable Transportation in Developing Countries Brochure, 2005. Available from: 〈http://www.ead.ae/TacSoft/FileManager/Conferences%20&%20Exhibitions/2005/Brochure.pdf〉 (accessed 4.06.2008).

- Gudmundsson, 2007 Gudmundsson, H., 2007. Implementing Sustainable Urban Transportation in Scandinavia. The 2007 Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting CD-ROM, Washington D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

- Hall, 2002 R.P. Hall; Introducing the Concept of Sustainable Transportation to the US DOT through the Reauthorization of TEA-21; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA (2002)

- Hall, 2006 Hall, R.P., 2006. Understanding and Applying the Concept of Sustainable Development to Transportation Planning and Decision-Making in the US, MIT Ph.D. Thesis.

- Hall and Sussman, 2007 Hall, R.P., Sussman, J.M., 2007. Promoting the concept of sustainable transportation within the federal system—The need to reinvent the US DOT. The 2007 Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting CD-ROM. Washington D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

- Hall and Sussman, 2007 Hall, Ralph P., Sussman, J.M., 2007. Promoting the Concept of Sustainable Transportation within the Federal System—The Need to Reinvent the US DOT. Paper submitted to the 86thAnnual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board January 21–25, 2007, in Washington, D.C. Available from: 〈http://esd.mit.edu/wps/esd-wp-2006-13.pdf〉 (accessed 5.01.2012)

- Hirschi et al., 2002 C. Hirschi, W. Schenkel, T. Widmer; Designing sustainable transportation policy for acceptance: A comparison of Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland; German Policies Studies/Politikfeldanalyse, 2 (2002), p. 4

- Jeon et al., 2007 Jeon, C.M., Amekudzi, A.A., Guensler, R.L., 2007. Evaluating transportation system sustainability: Atlanta Metropolitan Region. The 2007 Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting CD-ROM. Washington D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

- Jeon and Amekudzi, 2005 C.M. Jeon, A. Amekudzi; Addressing sustainability in transportation systems: Definitions, indicators, and metrics; Journal of Infrastructure Systems, 11 (2005), p. 1

- Lagan and McKenzie, 2004 C. Lagan, J. McKenzie; The EMBARQ Background Paper on Global Transportation and Motor Vehicle Growth in the Developing World—Implications for the Environment; The World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C (2004)

- Lee et al., 2002 R.W. Lee, P. Wack, J. Deertrack, S. Duiven, L. Wise; The California General Plan Process and Sustainable Transportation Planning; San Jose State University, Mineta Transportation Institute. San Jose, CA (2002)

- Litman, 2003 T. Litman; Reinvent Transportation: Exploring the Paradigm Shift Needed to Reconcile Transportation and Sustainability Objectives; Victoria Transport Policy Institute, Victoria, Canada (2003)

- Litman, 2007 T. Litman; Developing indicators for comprehensive and sustainable transport planning; Transportation Research Record, 2017 (1) (2007), pp. 10–15

- Litman, 2008 Litman, T., 2008. Sustainable Transportation Indicators: A Recommended Research Program for Developing Sustainable Transportation Indicators, presented at the 2009 Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting, Washington, D.C.

- Litman and Burwell, 2006 T. Litman, D. Burwell; Issues in sustainable transportation; International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 6 (4) (2006)

- Macario and Marques, 2007 Macario, R., Marques, C.F., 2007. Transferability of Sustainable Urban Mobility Measures. The 2007 Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting CD-ROM. Washington D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

- Mineta Transportation Institute, 2002 Mineta Transportation Institute; The California General Plan Process and Sustainable Transportation Planning; San José State University, San Jose, CA (2002)

- Newman and Kenworthy, 1999 P. Newman, J. Kenworthy; Sustainability and Cities; Island Press, Washington D.C (1999)

- OECD, 1996 OECD, 1996. OECD Proceedings: Towards Sustainable Transportation. Conference Organized by the OECD, Hosted by the Government of Canada, Vancouver, British Columbia, March 24–27. Available from: 〈www.oecd.org/dataoecd/28/54/2396815.pdf〉 (accessed 2.06.2008).

- Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), 2006 Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), 2006. Oregon Transportation Plan Update: Sustainable Transportation and Sustainable Development. Available from: 〈www.oregon.gov/ODOT/TD/TP/docs/otpPubs/SustainTransDev.pdf〉 (accessed 4.06.2008)

- ODOT, 2008 ODOT; The Oregon Department of Transportation Sustainability Plan; Salem, OR (2008)