| (212 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Abstract== | ==Abstract== | ||

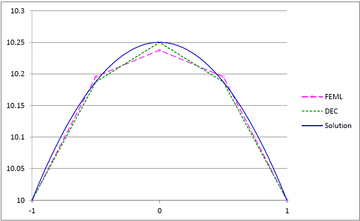

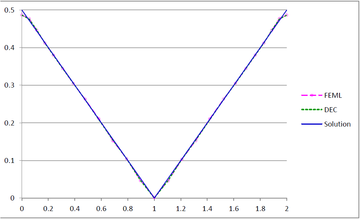

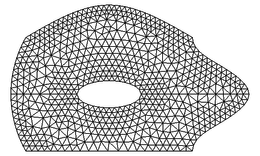

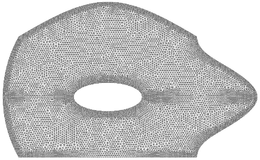

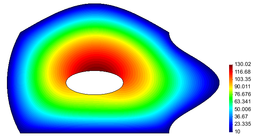

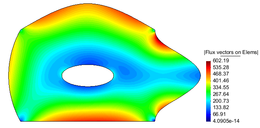

We revisit the theory of Discrete Exterior Calculus (DEC) in 2D for general triangulations, relying only on Vector Calculus and Matrix Algebra. We present DEC numerical solutions of the Poisson equation and compare them against those found using the Finite Element Method with linear elements (FEML). | We revisit the theory of Discrete Exterior Calculus (DEC) in 2D for general triangulations, relying only on Vector Calculus and Matrix Algebra. We present DEC numerical solutions of the Poisson equation and compare them against those found using the Finite Element Method with linear elements (FEML). | ||

| − | ==1 Introduction== | + | '''Keywords''': Discrete element method, Poisson equation |

| + | |||

| + | ==1. Introduction== | ||

| − | The purpose of this paper is to introduce the theory of Discrete Exterior Calculus (DEC) to the widest possible audience and, therefore, we will rely mainly on Vector Calculus and Matrix Algebra. Discrete Exterior Calculus is a relatively new method for solving partial differential equations <span id='citeF-8'></span>[[#cite-8|[8]]] based on the idea of discretizing the mathematical theory of Exterior Differential Calculus, a theory that goes back to | + | The purpose of this paper is to introduce the theory of Discrete Exterior Calculus (DEC) to the widest possible audience and, therefore, we will rely mainly on Vector Calculus and Matrix Algebra. Discrete Exterior Calculus is a relatively new method for solving partial differential equations <span id='citeF-8'></span>[[#cite-8|[8]]] based on the idea of discretizing the mathematical theory of Exterior Differential Calculus, a theory that goes back to Cartan <span id='citeF-3'></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]] and is fundamental in the areas of Differential Geometry and Differential Topology. Although Exterior Differential Calculus is an abstract mathematical theory, it has been introduced in various fields such as in digital geometry processing <span id='citeF-4'></span>[[#cite-4|[4]]], numerical schemes for partial differential equations <span id='citeF-8'></span><span id='citeF-1'></span>[[#cite-8|[1,8]]], etc. |

In his PhD thesis <span id='citeF-8'></span>[[#cite-8|[8]]], Hirani laid down the fundamental concepts of Discrete Exterior Calculus (DEC), using discrete combinatorial and geometric operations on simplicial complexes (in any dimension), proposing discrete equivalents for differential forms, vector fields, differential and geometric operators, etc. Perhaps the first numerical application of DEC to PDE was given in <span id='citeF-9'></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]] in order to solve Darcy flow and Poisson's equation. In <span id='citeF-7'></span>[[#cite-7|[7]]], the authors develop a modification of DEC and show that in simple cases (e.g. flat geometry and regular meshes), the equations resulting from DEC are equivalent to classical numerical schemes such as finite difference or finite volume discretizations. In <span id='citeF-11'></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]], the authors used DEC to solve the Navier-Stokes equations and, in <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]] DEC was used with a discrete lattice model to simulate elasticity, plasticity and failure of isotropic materials. | In his PhD thesis <span id='citeF-8'></span>[[#cite-8|[8]]], Hirani laid down the fundamental concepts of Discrete Exterior Calculus (DEC), using discrete combinatorial and geometric operations on simplicial complexes (in any dimension), proposing discrete equivalents for differential forms, vector fields, differential and geometric operators, etc. Perhaps the first numerical application of DEC to PDE was given in <span id='citeF-9'></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]] in order to solve Darcy flow and Poisson's equation. In <span id='citeF-7'></span>[[#cite-7|[7]]], the authors develop a modification of DEC and show that in simple cases (e.g. flat geometry and regular meshes), the equations resulting from DEC are equivalent to classical numerical schemes such as finite difference or finite volume discretizations. In <span id='citeF-11'></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]], the authors used DEC to solve the Navier-Stokes equations and, in <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]] DEC was used with a discrete lattice model to simulate elasticity, plasticity and failure of isotropic materials. | ||

| Line 32: | Line 15: | ||

The paper is organized as follows. In Section [[#2 2D Exterior Differential Calculus as Vector Calculus|2]], we introduce the wedge product of vectors and the ''geometric'' Hodge star operator, and rewrite Green's theorem appropriately in order to display the duality between the differentiation and the boundary operators. In Section [[#3 Discrete Exterior Calculus|3]], we present the operators of DEC (mesh, dual mesh, discrete derivation, discrete Hodge star operator), showing simple examples throughout. In Section [[#4 DEC for general triangulations|4]], we present the formulation of DEC on arbitrary triangulations. In Section [[#5 Numerical examples|5]], we present the numerical solution of a Poisson equation with DEC and FEML, in order to compare their performance. In Section [[#6 Conclusions|6]], we present our conclusions. | The paper is organized as follows. In Section [[#2 2D Exterior Differential Calculus as Vector Calculus|2]], we introduce the wedge product of vectors and the ''geometric'' Hodge star operator, and rewrite Green's theorem appropriately in order to display the duality between the differentiation and the boundary operators. In Section [[#3 Discrete Exterior Calculus|3]], we present the operators of DEC (mesh, dual mesh, discrete derivation, discrete Hodge star operator), showing simple examples throughout. In Section [[#4 DEC for general triangulations|4]], we present the formulation of DEC on arbitrary triangulations. In Section [[#5 Numerical examples|5]], we present the numerical solution of a Poisson equation with DEC and FEML, in order to compare their performance. In Section [[#6 Conclusions|6]], we present our conclusions. | ||

| − | ==2 2D Exterior Differential Calculus as Vector Calculus== | + | ==2. 2D Exterior Differential Calculus as Vector Calculus== |

In this section we introduce two geometric operators (the wedge product and the Hodge star) and explain how to use them together with the gradient operator in order to obtain the Laplacian. | In this section we introduce two geometric operators (the wedge product and the Hodge star) and explain how to use them together with the gradient operator in order to obtain the Laplacian. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 28: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\textstyle \ | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\textstyle \wedge ^2\mathbb{R}^2</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 56: | Line 39: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\mathbb{R}, \quad \quad \mathbb{R}^2, \quad \quad \ | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\mathbb{R}, \quad \quad \mathbb{R}^2, \quad \quad \wedge^2\mathbb{R}^2</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 71: | Line 54: | ||

|} | |} | ||

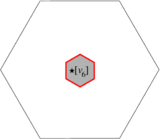

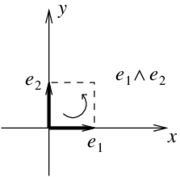

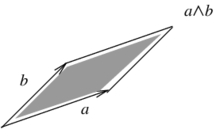

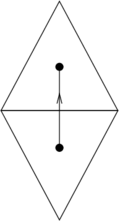

| − | which is read as "<math display="inline">e_1</math> wedge <math display="inline">e_2</math>" ( | + | which is read as "<math display="inline">e_1</math> wedge <math display="inline">e_2</math>" (Figure [[#lb-2.1|1]]). |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_6178_text-Square00-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_6178_text-Square00-eps-converted-to.png|180px]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 1'''. Wedge product of two vectors |

| − | |} | + | |} |

| + | |||

In <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^2</math>, this represents an “element” of unit area. | In <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^2</math>, this represents an “element” of unit area. | ||

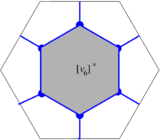

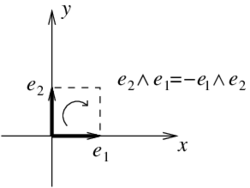

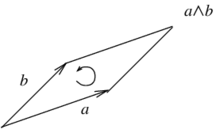

| − | Note that if we list the vectors in the opposite order, we have a different orientation and, therefore, the algebraic objects must satisfy <math display="inline">e_2\wedge e_1=-e_1\wedge e_2</math> ( | + | Note that if we list the vectors in the opposite order, we have a different orientation and, therefore, the algebraic objects must satisfy <math display="inline">e_2\wedge e_1=-e_1\wedge e_2</math> (Figure [[#lb-2.1|2]]). |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width:35%;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_6648_text-Square01-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_6648_text-Square01-eps-converted-to.png|250px|Change of orientation of the parallelogram implies anticommutativity in the wedge product of two vectors.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 2 | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 2'''. Change of orientation of the parallelogram implies anticommutativity in the wedge product of two vectors |

| − | |} | + | |} |

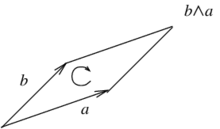

| − | More generally, given two vectors <math display="inline">a,b\in \mathbb{R}^2</math>, their wedge product <math display="inline">a\wedge b</math> looks as follows ( | + | More generally, given two vectors <math display="inline">a,b\in \mathbb{R}^2</math>, their wedge product <math display="inline">a\wedge b</math> looks as follows (Figure [[#lb-2.1|3]]). |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_4688_text-Parallelogram-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_4688_text-Parallelogram-eps-converted-to.png|220px|The wedge product of the vectors <math>a</math> and <math>b</math>.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 3'''. The wedge product of the vectors <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> |

| − | |} | + | |} |

The properties of the wedge product are | The properties of the wedge product are | ||

| − | * it is anticommutative: <math display="inline">a\wedge b = - b\wedge a</math> ( | + | * it is anticommutative: <math display="inline">a\wedge b = - b\wedge a</math> (Figure [[#lb-2.1|4]]) |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_4197_text-ParalPos-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_4197_text-ParalPos-eps-converted-to.png|220px|]] |

| − | | | + | |style="padding:10px;"|[[File:Review_239195285364_6087_text-ParalNeg-eps-converted-to.png|220px|]] |

| − | [[File:Review_239195285364_6087_text-ParalNeg-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan=" | + | | colspan="2" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 4'''. Anticommutativity of the wedge product |

| − | |} | + | |} |

| − | |||

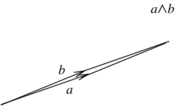

| − | + | * <math display="inline">a\wedge a = 0</math> since it is a parallelogram with area zero (Figure [[#lb-2.1|5]]) | |

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_7320_text-ParalZero-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_7320_text-ParalZero-eps-converted-to.png|180px]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 5'''. Parallelogram with very small area, depicting what happens when <math>b</math> tends to <math>a</math> |

| − | |} | + | |} |

| + | |||

* it is distributive | * it is distributive | ||

| Line 131: | Line 116: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(a + b )\wedge c = a\wedge c + b\wedge c | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(a + b )\wedge c = a\wedge c + b\wedge c</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 141: | Line 126: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(a \wedge b )\wedge c = a\wedge (b \wedge c) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(a \wedge b )\wedge c = a\wedge (b \wedge c)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 152: | Line 137: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>a= (a_1,a_2)\,\, = a_1 e_1 + a_2 e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>a= (a_1,a_2)\,\, = a_1 e_1 + a_2 e_2</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> b= (b_1,b_2)\,\, \,= b_1 e_1 + b_2 e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> b= (b_1,b_2)\,\, \,= b_1 e_1 + b_2 e_2 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 171: | Line 156: | ||

| style="text-align: center;" | <math> =a_1b_2\, e_1\wedge e_2 - a_2b_1\, e_1\wedge e_2 </math> | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> =a_1b_2\, e_1\wedge e_2 - a_2b_1\, e_1\wedge e_2 </math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> =(a_1b_2 - a_2b_1)\, e_1\wedge e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> =(a_1b_2 - a_2b_1)\, e_1\wedge e_2 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 199: | Line 184: | ||

| style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star e_1 = e_2</math> | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star e_1 = e_2</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}\star e_2 = -e_1 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}\star e_2 = -e_1 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 210: | Line 195: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>w\wedge (\star v) = (w\cdot v) \, e_1\wedge e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>w\wedge (\star v) = (w\cdot v) \, e_1\wedge e_2</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 221: | Line 206: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>v\wedge (\star v) = |v|^2 \, e_1\wedge e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>v\wedge (\star v) = |v|^2 \, e_1\wedge e_2</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 227: | Line 212: | ||

which means that <math display="inline">v</math> and <math display="inline">\star v</math> form a square of area <math display="inline">|v|^2</math>. Thus, the Hodge star operator on a vector <math display="inline">v\in \mathbb{R}^2</math> can be thought of as finding the vector that makes with <math display="inline">v</math> a positively oriented square of area <math display="inline">\vert v\vert ^2</math>. | which means that <math display="inline">v</math> and <math display="inline">\star v</math> form a square of area <math display="inline">|v|^2</math>. Thus, the Hodge star operator on a vector <math display="inline">v\in \mathbb{R}^2</math> can be thought of as finding the vector that makes with <math display="inline">v</math> a positively oriented square of area <math display="inline">\vert v\vert ^2</math>. | ||

| − | It is somewhat less intuitive to work out the Hodge star of a bivector. First of all, we have to treat bivectors as vectors of a different space, namely the space of bivectors <math display="inline">\textstyle \ | + | It is somewhat less intuitive to work out the Hodge star of a bivector. First of all, we have to treat bivectors as vectors of a different space, namely the space of bivectors <math display="inline">\textstyle \wedge ^2\mathbb{R}^2</math>. Secondly, the length of a bivector <math display="inline">v\wedge w</math> is its area |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 234: | Line 219: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{length}(v\wedge w):= {Area}(v\wedge w) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{length}(v\wedge w):= {Area}(v\wedge w)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 256: | Line 241: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(v\wedge w)\wedge \star (v\wedge w) = {Area}(v\wedge w)^2 e_1\wedge e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(v\wedge w)\wedge \star (v\wedge w) = {Area}(v\wedge w)^2 e_1\wedge e_2 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 267: | Line 252: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star (v\wedge w)={Area}(v\wedge w) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star (v\wedge w)={Area}(v\wedge w)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 278: | Line 263: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star (e_1\wedge e_2) = 1 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star (e_1\wedge e_2) = 1</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 289: | Line 274: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star \lambda =\lambda \, e_1\wedge e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star \lambda =\lambda \, e_1\wedge e_2</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 302: | Line 287: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nabla f = {\partial f\over \partial x}e_1+{\partial f\over \partial y}e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nabla f = {\partial f\over \partial x}e_1+{\partial f\over \partial y}e_2</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 313: | Line 298: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star \nabla f = {\partial f\over \partial x} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star \nabla f = {\partial f\over \partial x} \star e_1+{\partial f\over \partial y} \star e_2</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> = {\partial f\over \partial x}e_2-{\partial f\over \partial y}e_1 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> = {\partial f\over \partial x}e_2-{\partial f\over \partial y}e_1</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 326: | Line 311: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nabla \wedge \star \nabla f := \nabla \left({\partial f\over \partial x}\right)\wedge e_2-\nabla \left({\partial f\over \partial y}\right)\wedge e_1</math> | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nabla^\wedge \star \nabla f := \nabla \left({\partial f\over \partial x}\right)\wedge e_2-\nabla \left({\partial f\over \partial y}\right)\wedge e_1</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| style="text-align: center;" | <math> = \left({\partial ^2 f\over \partial x^2}e_1+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial y\partial x}e_2\right)\wedge e_2 -\left({\partial ^2 f\over \partial x\partial y}e_1+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial ^2 y}e_2\right)\wedge e_1</math> | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> = \left({\partial ^2 f\over \partial x^2}e_1+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial y\partial x}e_2\right)\wedge e_2 -\left({\partial ^2 f\over \partial x\partial y}e_1+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial ^2 y}e_2\right)\wedge e_1</math> | ||

| Line 332: | Line 317: | ||

| style="text-align: center;" | <math> = {\partial ^2 f\over \partial x^2}e_1\wedge e_2+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial y\partial x}e_2\wedge e_2 -{\partial ^2 f\over \partial x\partial y}e_1\wedge e_1-{\partial ^2 f\over \partial ^2 y}e_2\wedge e_1</math> | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> = {\partial ^2 f\over \partial x^2}e_1\wedge e_2+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial y\partial x}e_2\wedge e_2 -{\partial ^2 f\over \partial x\partial y}e_1\wedge e_1-{\partial ^2 f\over \partial ^2 y}e_2\wedge e_1</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> = \left({\partial ^2 f\over \partial x^2}+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial ^2 y}\right)e_1\wedge e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> = \left({\partial ^2 f\over \partial x^2}+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial ^2 y}\right)e_1\wedge e_2 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 343: | Line 328: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star \nabla \wedge \star \nabla (f) = {\partial ^2 f\over \partial x^2}+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial ^2 y} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star \nabla ^\wedge \star \nabla (f) = {\partial ^2 f\over \partial x^2}+{\partial ^2 f\over \partial ^2 y} </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 351: | Line 336: | ||

(i) This rather convoluted looking way of computing the Laplacian of a function is based on Exterior Differential Calculus, a theory that generalizes the operators of vector calculus (gradient, curl and divergence) to arbitrary dimensions, and is the basis for the differential topological theory of deRham cohomology. | (i) This rather convoluted looking way of computing the Laplacian of a function is based on Exterior Differential Calculus, a theory that generalizes the operators of vector calculus (gradient, curl and divergence) to arbitrary dimensions, and is the basis for the differential topological theory of deRham cohomology. | ||

| − | (ii) We would like to emphasize the necessity of using the Hodge star operator <math display="inline"> | + | (ii) We would like to emphasize the necessity of using the Hodge star operator <math display="inline">\star</math> in order to make the combination of differentiation and wedge product produce the correct answer. |

===2.4 Duality in Green's theorem=== | ===2.4 Duality in Green's theorem=== | ||

| Line 377: | Line 362: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>F= Le_1+Me_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>F= Le_1+Me_2</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 396: | Line 381: | ||

| style="text-align: center;" | <math> ={\partial L\over \partial y}e_2\wedge e_1 +{\partial M\over \partial x}e_1\wedge e_2</math> | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> ={\partial L\over \partial y}e_2\wedge e_1 +{\partial M\over \partial x}e_1\wedge e_2</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> =\left({\partial M\over \partial x} -{\partial L\over \partial y}\right)e_1\wedge e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> =\left({\partial M\over \partial x} -{\partial L\over \partial y}\right)e_1\wedge e_2 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 407: | Line 392: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star \nabla ^\wedge (L e_1 + M e_2) =\left({\partial M\over \partial x} -{\partial L\over \partial y}\right) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star \nabla ^\wedge (L e_1 + M e_2) =\left({\partial M\over \partial x} -{\partial L\over \partial y}\right) </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 444: | Line 429: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\int _C (L,M)\cdot (dx,dy) = \ll (L,M), C\gg | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\int _C (L,M)\cdot (dx,dy) = \ll (L,M), C\gg </math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \int _D\nabla ^\wedge (L, M)dxdy = \ll \nabla ^\wedge (L,M), D\gg | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \int _D\nabla ^\wedge (L, M)dxdy = \ll \nabla ^\wedge (L,M), D\gg </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 457: | Line 442: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\ll \nabla ^\wedge (L,M), D\gg \,\,=\,\,\ll (L,M), \partial D\gg | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\ll \nabla ^\wedge (L,M), D\gg \,\,=\,\,\ll (L,M), \partial D\gg</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 465: | Line 450: | ||

'''Remark'''. The previous observation is fundamental in the development of DEC, since the boundary operator is well understood and easy to calculate on meshes. | '''Remark'''. The previous observation is fundamental in the development of DEC, since the boundary operator is well understood and easy to calculate on meshes. | ||

| − | ==3 Discrete Exterior Calculus== | + | ==3. Discrete Exterior Calculus== |

Now we will discretize the differentiation operator <math display="inline">\nabla ^\wedge </math> presented above. We will start by describing the discrete version of the boundary operator on simplices/triangles. Afterwards, we will treat the differentiation operator as the transpose of the boundary operator. | Now we will discretize the differentiation operator <math display="inline">\nabla ^\wedge </math> presented above. We will start by describing the discrete version of the boundary operator on simplices/triangles. Afterwards, we will treat the differentiation operator as the transpose of the boundary operator. | ||

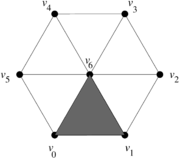

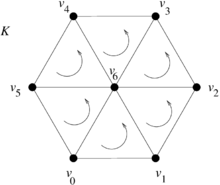

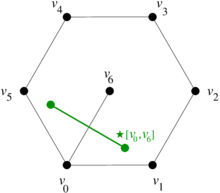

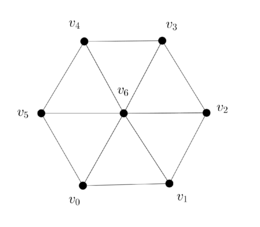

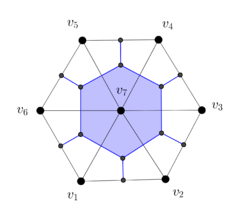

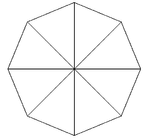

| − | We are interested in using certain geometric subsets of a given triangular mesh of a 2D region. Such subsets include vertices/nodes, edges/sides and faces/triangles. We will describe each one of them by means of the ordered list of vertices whose convex closure constitutes the subset of interest. For instance, consider the triangular mesh of the planar hexagonal region in Figure [[#3 Discrete Exterior Calculus| | + | We are interested in using certain geometric subsets of a given triangular mesh of a 2D region. Such subsets include vertices/nodes, edges/sides and faces/triangles. We will describe each one of them by means of the ordered list of vertices whose convex closure constitutes the subset of interest. For instance, consider the triangular mesh of the planar hexagonal region in Figure [[#3 Discrete Exterior Calculus|6]], |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_2873_text-Region-01-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_2873_text-Region-01-eps-converted-to.png|180px|]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 6'''. Triangular mesh of a planar hexagonal region |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

where the shaded triangle will be denoted by <math display="inline">[v_0,v_1,v_6]</math>, and its edge joining the vertices <math display="inline">v_0</math> and <math display="inline">v_1</math> will be denoted by <math display="inline">[v_0,v_1]</math>. For the sake of notational consistency, we will denote the vertices also enclosed in brackets, e.g. <math display="inline">[v_0]</math>. | where the shaded triangle will be denoted by <math display="inline">[v_0,v_1,v_6]</math>, and its edge joining the vertices <math display="inline">v_0</math> and <math display="inline">v_1</math> will be denoted by <math display="inline">[v_0,v_1]</math>. For the sake of notational consistency, we will denote the vertices also enclosed in brackets, e.g. <math display="inline">[v_0]</math>. | ||

| − | ===3.1 Boundary operator=== | + | ===3.1 Boundary operator and discrete derivative=== |

There is a well known boundary operator <math display="inline">\partial </math> for oriented triangles, edges and points: | There is a well known boundary operator <math display="inline">\partial </math> for oriented triangles, edges and points: | ||

| Line 487: | Line 471: | ||

* For points/vertices: | * For points/vertices: | ||

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_9903_text-boundary00-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_9903_text-boundary00-eps-converted-to.png|80px|]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 7'''. Boundary of a vertex: <math>\partial [v_0] = 0</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 497: | Line 481: | ||

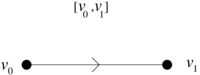

* For sides/edges: | * For sides/edges: | ||

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_1507_text-boundary01-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_1507_text-boundary01-eps-converted-to.png|200px|]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 8'''. Boundary of an edge: <math>\partial [v_0,v_1] = [v_1] - [v_0]</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

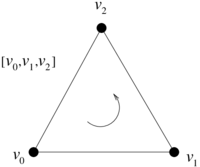

* For faces/triangles: | * For faces/triangles: | ||

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_1837_text-boundary02-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_1837_text-boundary02-eps-converted-to.png|200px|]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 9'''. Boundary of a face: <math>\partial [v_0,v_1,v_2] = [v_1,v_2] - [v_0,v_2]+[v_0,v_1]</math> |

|} | |} | ||

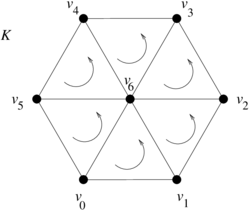

| − | '''Example'''. Let us consider again the mesh of the planar hexagonal (with oriented triangles) in Figure [[#3.1 Boundary operator| | + | '''Example'''. Let us consider again the mesh of the planar hexagonal (with oriented triangles) in Figure [[#3.1 Boundary operator|10]]. |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_6355_text-boundary04-eps-converted-to.png| | + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_6355_text-boundary04-eps-converted-to.png|250px|]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="1" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 10'''. Oriented triangular mesh of a planar hexagonal region |

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

We will denote a triangle by the list of its vertices listed in order according to the orientation of the tringle. Thus, we have the following ordered lists: | We will denote a triangle by the list of its vertices listed in order according to the orientation of the tringle. Thus, we have the following ordered lists: | ||

| Line 534: | Line 517: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \{ | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \{[v_0,v_1,v_6],[v_1,v_2,v_6],[v_2,v_3,v_6], [v_3,v_4,v_6],[v_4,v_5,v_6],[v_5,v_0,v_6]\} </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 544: | Line 527: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \{ [v_0,v_6], [v_1,v_6], [v_2,v_6], [v_3,v_6], [v_4,v_6], [v_5,v_6], [v_0,v_1], [v_1,v_2], [v_2,v_3], [v_3,v_4], [v_4,v_5], [v_5,v_0] \} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \{ [v_0,v_6], [v_1,v_6], [v_2,v_6], [v_3,v_6], [v_4,v_6], [v_5,v_6], [v_0,v_1], [v_1,v_2], [v_2,v_3], [v_3,v_4], [v_4,v_5], [v_5,v_0] \} </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 554: | Line 537: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \{ [v_0],[v_1],[v_2],[v_3],[v_4],[v_5],[v_6] \} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \{ [v_0],[v_1],[v_2],[v_3],[v_4],[v_5],[v_6] \} </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | A key idea in DEC is to consider each face as an element of a basis of a vector space. Namely, coordinate vectors are associated to faces as follows: | + | A key idea in DEC is to consider each face as an element of a basis of a vector space. Namely, column coordinate vectors are associated to faces as follows: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 565: | Line 548: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>[v_0,v_1,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>[v_0,v_1,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_1,v_2,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_1,v_2,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_2,v_3,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_2,v_3,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_3,v_4,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_3,v_4,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_4,v_5,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_4,v_5,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_5,v_0,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {}[v_5,v_0,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1)^T</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 586: | Line 569: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{} [v_0,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{} [v_0,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_4,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_4,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_5,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_5,v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_0,v_1] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_0,v_1] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1,v_2] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1,v_2] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2,v_3] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2,v_3] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3,v_4] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3,v_4] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_4,v_5] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_4,v_5] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_5,v_0] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_5,v_0] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1)^T</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 619: | Line 602: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{} [v_0] \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{} [v_0] \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1] \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1] \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_4] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_4] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_5] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_5] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,1) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_6] \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,1)^T</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 642: | Line 625: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial [v_0,v_1,v_6] = [v_1,v_6] - [v_0,v_6]+[v_0,v_1] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial [v_0,v_1,v_6] = [v_1,v_6] - [v_0,v_6]+[v_0,v_1]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_1,v_2,v_6] = [v_2,v_6] - [v_1,v_6]+[v_1,v_2] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_1,v_2,v_6] = [v_2,v_6] - [v_1,v_6]+[v_1,v_2]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_2,v_3,v_6] = [v_3,v_6] - [v_2,v_6]+[v_2,v_3] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_2,v_3,v_6] = [v_3,v_6] - [v_2,v_6]+[v_2,v_3]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_3,v_4,v_6] = [v_4,v_6] - [v_3,v_6]+[v_3,v_4] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_3,v_4,v_6] = [v_4,v_6] - [v_3,v_6]+[v_3,v_4]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_4,v_5,v_6] = [v_5,v_6] - [v_4,v_6]+[v_4,v_5] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_4,v_5,v_6] = [v_5,v_6] - [v_4,v_6]+[v_4,v_5]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_5,v_0,v_6] = [v_0,v_6] - [v_5,v_6]+[v_5,v_0] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_5,v_0,v_6] = [v_0,v_6] - [v_5,v_6]+[v_5,v_0] </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | which, under the previous assignments of coordinate vectors, corresponds to the linear transformation given by the following matrix | + | which, under the previous assignments of coordinate vectors, corresponds to the linear transformation given by the following matrix which will multiply the column coordinate vectors on the left |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 663: | Line 646: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial _{2,1}=\left(\begin{array}{rrrrrr} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 &0 & 0\\ 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 &0 &0 & 1 & -1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1\\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 &0 &0 &0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial _{2,1}=\left(\begin{array}{rrrrrr} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 &0 & 0\\ 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 &0 &0 & 1 & -1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1\\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 &0 &0 &0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 674: | Line 657: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial [v_0,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_0] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial [v_0,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_0]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_1,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_1] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_1,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_1]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_2,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_2] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_2,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_2]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_3,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_3] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_3,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_3]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_4,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_4] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_4,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_4]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_5,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_5] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_5,v_6] = [v_6] - [v_5]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_0,v_1] = [v_1] - [v_0] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_0,v_1] = [v_1] - [v_0]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_1,v_2] = [v_2] - [v_1] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_1,v_2] = [v_2] - [v_1]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_2,v_3] = [v_3] - [v_2] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_2,v_3] = [v_3] - [v_2]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_3,v_4] = [v_4] - [v_3] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_3,v_4] = [v_4] - [v_3]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_4,v_5] = [v_5] - [v_4] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_4,v_5] = [v_5] - [v_4]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_5,v_0] = [v_0] - [v_5] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial [v_5,v_0] = [v_0] - [v_5] </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 707: | Line 690: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial _{1,0}=\left( \begin{array}{rrrrrr|rrrrrr} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1\\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial _{1,0}=\left( \begin{array}{rrrrrr|rrrrrr} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1\\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 731: | Line 714: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nabla ^\wedge _{0,1}=\left(\begin{array}{rrrrrrr} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1\\ -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1& 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1& 0 \end{array} \right) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nabla ^\wedge _{0,1}=\left(\begin{array}{rrrrrrr} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1\\ -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1& 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1& 0 \end{array} \right)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 739: | Line 722: | ||

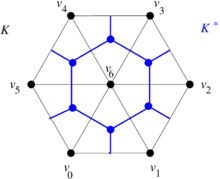

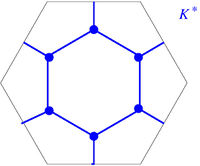

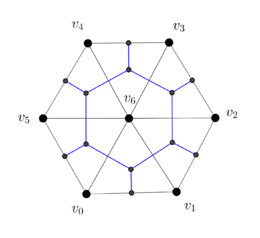

In order to discretize the Hodge star operator, we must first introduce the notion of the dual mesh of a triangular mesh. | In order to discretize the Hodge star operator, we must first introduce the notion of the dual mesh of a triangular mesh. | ||

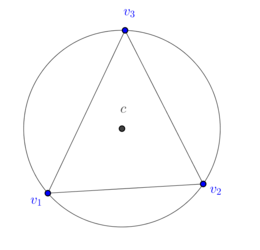

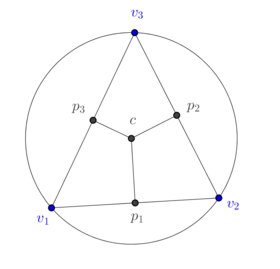

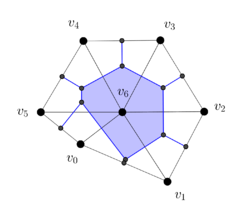

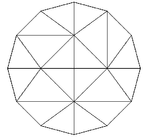

| − | Consider the triangular mesh <math display="inline">K</math> in Figure [[#3.2 Dual mesh| | + | Consider the triangular mesh <math display="inline">K</math> in Figure [[#3.2 Dual mesh|11]](a). The construction of the dual mesh <math display="inline">K^*</math> is carried out as follows: |

| − | * The vertices of the dual mesh <math display="inline">K^*</math> are the circumcenters of the faces/triangles of the original mesh (the blue dots in Figures [[#3.2 Dual mesh| | + | * The vertices of the dual mesh <math display="inline">K^*</math> are the circumcenters of the faces/triangles of the original mesh (the blue dots in Figures [[#3.2 Dual mesh|11]](b) and [[#3.2 Dual mesh|11]](c)). For instance, the dual of the face <math display="inline">[v_0,v_1,v_6]</math> will be denoted by <math display="inline">[v_0,v_1,v_6]^*</math>. |

| − | * The edges of <math display="inline">K^*</math> are the straight line segments joining the circumcenters of two adjacent triangles (those which share an edge). Note that the resulting line segments are orthogonal to one of the original edges (the blue straight line segments in in Figures [[#3.2 Dual mesh| | + | * The edges of <math display="inline">K^*</math> are the straight line segments joining the circumcenters of two adjacent triangles (those which share an edge). Note that the resulting line segments are orthogonal to one of the original edges (the blue straight line segments in in Figures [[#3.2 Dual mesh|11]](b) and [[#3.2 Dual mesh|11]](c)). For instance, the dual of the edge <math display="inline">[v_0,v_6]</math> will be denoted by <math display="inline">[v_0,v_6]^*</math>. |

| − | * The faces or cells of <math display="inline">K^*</math> are the areas enclosed by the new polygons determined by the new edges. For instance, the dual of the | + | * The faces or cells of <math display="inline">K^*</math> are the areas enclosed by the new polygons determined by the new edges. For instance, the dual of the vertex <math display="inline">[v_6]</math> is the inner blue hexagon in in Figures [[#3.2 Dual mesh|11]](b) and [[#3.2 Dual mesh|11]](c) and will be denoted by <math display="inline">[v_6]^*</math>. |

| − | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" | |

| − | + | ||

| − | {| | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_6808_text-boundary04-eps-converted-to.png|220px|]] | ||

| + | | style="padding:10px;"|[[Image:Review_239195285364_2587_text-Dual00-eps-converted-to.png|220px|]] | ||

| + | | style="padding:10px;"|[[File:Review_239195285364_6445_Dual01-eps-converted-to.jpg|200px|]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| (a) | | (a) | ||

| (b) | | (b) | ||

| (c) | | (c) | ||

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="3" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="3" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 11'''. Dual mesh construction. (a) Triangular mesh <math>K</math>. (b) Dual mesh <math>K^*</math> superimposed on the mesh <math>K</math>. (c) Dual mesh <math>K^*</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

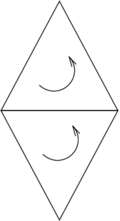

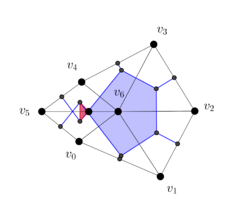

| − | {| | + | The orientation of the dual edges is given by the following recipe. If we have two adjacent triangles oriented as in Figure [[#3.2 Dual mesh|12]](a), the dual edge crossing the edge of adjacency is oriented as in Figure [[#3.2 Dual mesh|12]](b). |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" | |

| − | + | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_3618_text-TwoTriangles01-eps-converted-to.png|120px|]] | ||

| + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_1851_text-TwoTriangles02-eps-converted-to.png|120px|]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| (a) | | (a) | ||

| (b) | | (b) | ||

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan=" | + | | colspan="2" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 12'''. (a) Two adjacent oriented triangles. (b) Compatibly oriented dual edge |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

===3.3 Boundary operator on the dual mesh=== | ===3.3 Boundary operator on the dual mesh=== | ||

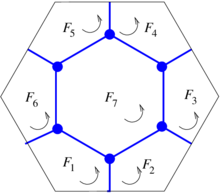

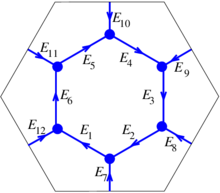

| − | Consider the dual mesh in Figure [[#3.3 Boundary operator on the dual mesh| | + | Consider the dual mesh in Figure [[#3.3 Boundary operator on the dual mesh|13]] with the given labels and orientations. |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_5980_text-Dual01a-eps-converted-to.png| | + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_5980_text-Dual01a-eps-converted-to.png|220px|]] |

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_7382_text-Dual01b-eps-converted-to.png| | + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_7382_text-Dual01b-eps-converted-to.png|220px|n]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="2" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="2" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 13'''. Oriented dual mesh |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 794: | Line 775: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_1 = E_{1} + E_{7} - E_{12} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_1 = E_{1} + E_{7} - E_{12}</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_2 = E_{2} - E_{7} + E_{8} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_2 = E_{2} - E_{7} + E_{8}</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_3 = E_{3} - E_{8} + E_{9} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_3 = E_{3} - E_{8} + E_{9} </math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_4 = E_{4} - E_{9} + E_{10} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_4 = E_{4} - E_{9} + E_{10}</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_5 = E_{5} - E_{10} + E_{11} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_5 = E_{5} - E_{10} + E_{11}</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_6 = E_{6} - E_{11} + E_{12} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_6 = E_{6} - E_{11} + E_{12}</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_7 = -E_{1}- E_{2}- E_{3}- E_{4}- E_{5}- E_{6} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \partial ^{dual}_{2,1} F_7 = -E_{1}- E_{2}- E_{3}- E_{4}- E_{5}- E_{6} </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 817: | Line 798: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>F_1 \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>F_1 \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_2 \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_2 \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_3 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_3 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_4 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_4 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_5 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_5 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_6 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_6 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_7 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,1) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> F_7 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,1)^T</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 840: | Line 821: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>E_1 \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>E_1 \longleftrightarrow (1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_2 \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_2 \longleftrightarrow (0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_3 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_3 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_4 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_4 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_5 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_5 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_6 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_6 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_7 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_7 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_8 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_8 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_9 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_9 \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_{10} \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_{10} \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_{11} \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_{11} \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0)^T</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_{12} \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> E_{12} \longleftrightarrow (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1)^T</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 873: | Line 854: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial _{2,1}^{dual}=\left(\begin{array}{rrrrrrr} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1\\ 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1& 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1& 0 \end{array} \right) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial _{2,1}^{dual}=\left(\begin{array}{rrrrrrr} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & -1\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1\\ 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1& 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1& 0 \end{array} \right)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 884: | Line 865: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial _{2,1}^{dual}=-\left(\partial _{1,0}\right)^T | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\partial _{2,1}^{dual}=-\left(\partial _{1,0}\right)^T</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 895: | Line 876: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nabla _{1,2}^{\wedge ,dual}=\left(\partial _{2,1}^{dual}\right)^T=-\partial _{1,0}=-\left(\nabla ^\wedge _{0,1}\right)^T | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\nabla _{1,2}^{\wedge ,dual}=\left(\partial _{2,1}^{dual}\right)^T=-\partial _{1,0}=-\left(\nabla ^\wedge _{0,1}\right)^T</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 901: | Line 882: | ||

===3.4 Discrete Hodge star=== | ===3.4 Discrete Hodge star=== | ||

| − | The discretization of the Hodge star <math display="inline">\star </math> uses the geometrical ideas described in Section [[#lb-2.2|2.2]] and the dual mesh. More precisely, the 2D Hodge star operator rotates a vector <math display="inline">90^\circ </math> counterclockwise. For the sake of clarity, let us focus on the edge <math display="inline">[v_0,v_6]</math>, its mesh dual <math display="inline">[v_0,v_6]^*</math> and its Hodge star image <math display="inline">\star [v_0,v_6]</math>. They are represented in Figure [[#3.4 Discrete Hodge star| | + | The discretization of the Hodge star <math display="inline">\star </math> uses the geometrical ideas described in Section [[#lb-2.2|2.2]] and the dual mesh. More precisely, the 2D Hodge star operator rotates a vector <math display="inline">90^\circ </math> counterclockwise. For the sake of clarity, let us focus on the edge <math display="inline">[v_0,v_6]</math>, its mesh dual <math display="inline">[v_0,v_6]^*</math> and its Hodge star image <math display="inline">\star [v_0,v_6]</math>. They are represented in Figure [[#3.4 Discrete Hodge star|14]]. |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_9611_text-Dual00a-eps-converted-to.png| | + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_9611_text-Dual00a-eps-converted-to.png|220px]] |

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_4015_text-Dual00aa-eps-converted-to.png| | + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_4015_text-Dual00aa-eps-converted-to.png|220px]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="2" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="2" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 14'''. Oriented dual mesh |

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

Since | Since | ||

| Line 918: | Line 900: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{length}(\star [v_0,v_6])={length}([v_0,v_6]) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{length}(\star [v_0,v_6])={length}([v_0,v_6])</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 929: | Line 911: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{1\over {length}([v_0,v_6]^*)}[v_0,v_6]^*= {1\over {length}([v_0,v_6])}\star [v_0,v_6] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{1\over {length}([v_0,v_6]^*)}[v_0,v_6]^*= {1\over {length}([v_0,v_6])}\star [v_0,v_6]</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 940: | Line 922: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>M_{1,1}=\left(\begin{array}{ccccc} {{length}([v_0,v_6]^*)\over {length}([v_0,v_6])} & 0 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & {{length}([v_1,v_6]^*)\over {length}([v_1,v_6])} & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & {{length}([v_2,v_6]^*)\over {length}([v_2,v_6])} & \dots & 0\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots &\vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \dots & {{length}([v_5,v_0]^*)\over {length}([v_5,v_0])} \end{array} \right) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>M_{1,1}=\left(\begin{array}{ccccc} {{length}([v_0,v_6]^*)\over {length}([v_0,v_6])} & 0 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & {{length}([v_1,v_6]^*)\over {length}([v_1,v_6])} & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & {{length}([v_2,v_6]^*)\over {length}([v_2,v_6])} & \dots & 0\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots &\vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \dots & {{length}([v_5,v_0]^*)\over {length}([v_5,v_0])} \end{array} \right)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 953: | Line 935: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star 1=e_1\wedge e_2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\star 1=e_1\wedge e_2</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 959: | Line 941: | ||

which geometrically means that the Hodge star <math display="inline">\star [v_6]</math> must be a polygon with area equal to 1 (classically, it is a parallelogram, but can also be a hexahedron of area 1 as in this example). | which geometrically means that the Hodge star <math display="inline">\star [v_6]</math> must be a polygon with area equal to 1 (classically, it is a parallelogram, but can also be a hexahedron of area 1 as in this example). | ||

| − | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center | + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; " |

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | |

| + | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''[[Image:Review_239195285364_3989_text-HodgeStarPoint01-eps-converted-to.png|160px|]]''</span></div> | ||

|} | |} | ||

However, in the dual mesh we have the polygon <math display="inline">[v_6]^*</math> | However, in the dual mesh we have the polygon <math display="inline">[v_6]^*</math> | ||

| − | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center | + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; " |

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | |

| + | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''[[Image:Review_239195285364_2797_text-HodgeStarPoint00-eps-converted-to.png|160px|]]''</span></div> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 978: | Line 962: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>[v_6]^*={Area}([v_6]^*)\, \star [v_6] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>[v_6]^*={Area}([v_6]^*)\, \star [v_6]</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 989: | Line 973: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> M_{0,2}=\left( \begin{array}{cccc} {Area}([v_0]^*) & 0 & \dots & 0\\ 0 & {Area}([v_1]^*) & \dots & 0\\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & {Area}([v_6]^*) \end{array} \right) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> M_{0,2}=\left( \begin{array}{cccc} {Area}([v_0]^*) & 0 & \dots & 0\\ 0 & {Area}([v_1]^*) & \dots & 0\\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & {Area}([v_6]^*) \end{array} \right)</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,006: | Line 990: | ||

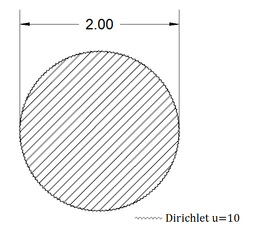

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\kappa \Delta f= q | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\kappa \Delta f= q</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,017: | Line 1,001: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\kappa \,\,\star \nabla ^\wedge \star \nabla (f) = q | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\kappa \,\,\star \nabla ^\wedge \star \nabla (f) = q </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Suppose that we wish to solve the equation | + | Suppose that we wish to solve the equation using the mesh <math display="inline">K</math>. Let us denote by <math display="inline">[f]</math> and <math display="inline">[q]</math> the column vector discretizations of the functions <math display="inline">K</math> and <math display="inline">q</math> at the nodes. According to DEC, the first derivation <math display="inline">\nabla(f)</math> is achieved left-multiplying <math display="inline">[f]</math> by the matrix <math display="inline">\nabla ^\wedge _{0,1}</math> of Subsection 3.1. |

| + | The resulting column vector is a collection of (unknown) directional derivative values of <math display="inline">f</math> assigned to the ordered set of edges. At | ||

| + | this point we need to transfer such a set of values to the ordered set of dual edges of the dual mesh with the appropriate geometrical scaling, which is achieved multiplying on the left by the matrix <math display="inline">M_{1,1}</math> of Subsection 3.4. Now, the discrete version of the second derivation <math display="inline">\nabla^\wedge</math> is given by left multiplication with the matrix <math display="inline">\nabla^\wedge_{1,2}</math> of Subsection 3.3, which gives a column vector of (unknown) values assigned to the ordered set of 2-dimensional cells of the dual mesh. Finally, the task of mapping such values (with the appropriate scaling) to the ordered set of vertices of the original mesh is achieved by left multiplication with the matrix <math display="inline">M_{2,0}</math> of Subsection 3.4. Thus, the Poisson equation is discretized as the matrix equation | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 1,032: | Line 1,018: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | Later on, it will be convenient to work with the equivalent system | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 1,043: | Line 1,029: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | ==4 DEC for general triangulations== | + | Note that the DEC-discretization of <math display="inline">\nabla(f)</math> is not a (discretized) flow vector. It is a collection of values |

| + | of directional derivatives of <math display="inline">f</math>, one such value for each oriented edge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==4. DEC for general triangulations== | ||

Since the boundary operator is really concerned with the connectivity of the mesh and does not change under deformation of the mesh, the change in the setup of DEC for a deformed mesh must be contained in the discrete Hodge star matrices. Since such matrices are computed in terms of lengths and areas of oriented elements of the mesh, we will now examine how those ingredients transform under deformation, a problem that was first considered in <span id='citeF-10'></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]]. | Since the boundary operator is really concerned with the connectivity of the mesh and does not change under deformation of the mesh, the change in the setup of DEC for a deformed mesh must be contained in the discrete Hodge star matrices. Since such matrices are computed in terms of lengths and areas of oriented elements of the mesh, we will now examine how those ingredients transform under deformation, a problem that was first considered in <span id='citeF-10'></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]]. | ||

| Line 1,049: | Line 1,038: | ||

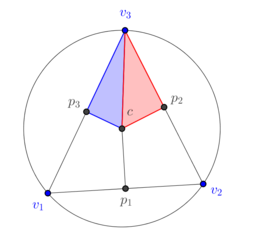

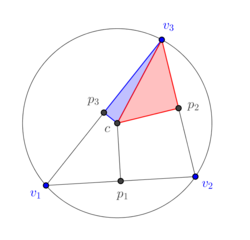

===4.1 Dual mesh of an arbitrary triangle=== | ===4.1 Dual mesh of an arbitrary triangle=== | ||

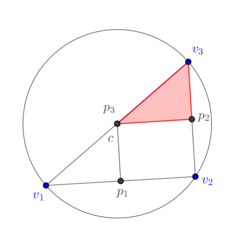

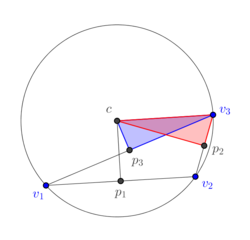

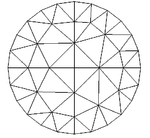

| − | In order to explain how to implement DEC for general triangulations, let us consider first a mesh consisting of a single well-centered triangle, as well as its dual mesh ( | + | In order to explain how to implement DEC for general triangulations, let us consider first a mesh consisting of a single well-centered triangle, as well as its dual mesh (Figure [[#4.1 Dual mesh of an arbitrary triangle|15]]). |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_2549_NewCircumscribedTriangle00.png| | + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_2549_NewCircumscribedTriangle00.png|260px|]] |

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_2438_NewCircumscribedTriangle00b.png| | + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_2438_NewCircumscribedTriangle00b.png|280px|]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="2" | '''Figure | + | | colspan="2" style="padding:10px;"| '''Figure 15'''. Well-centered triangle and its dual mesh |

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

The dual cells are given as follows: | The dual cells are given as follows: | ||

| Line 1,067: | Line 1,056: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{} [v_1,v_2,v_3]^*= [c] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>{} [v_1,v_2,v_3]^*= [c]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1,v_2]^*= [p_1,c] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1,v_2]^*= [p_1,c]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2,v_3]^*= [p_2,c] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2,v_3]^*= [p_2,c]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3,v_1]^*= [p_3,c] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3,v_1]^*= [p_3,c]</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1]^* = [v_1,p_1,c,p_3] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_1]^* = [v_1,p_1,c,p_3] </math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2]^* = [v_2,p_2,c,p_1] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_2]^* = [v_2,p_2,c,p_1] </math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3]^* = [v_3,p_3,c,p_2] | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> {} [v_3]^* = [v_3,p_3,c,p_2] </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Now consider the cell <math display="inline">[v_3]^* = [v_3,p_3,c,p_2]</math> subdivided as in Figure [[#4.1 Dual mesh of an arbitrary triangle| | + | Now consider the cell <math display="inline">[v_3]^* = [v_3,p_3,c,p_2]</math> subdivided as in Figure [[#4.1 Dual mesh of an arbitrary triangle|16]]. |

| − | {| | + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: auto;max-width: auto;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Review_239195285364_1856_NewCircumscribedTriangle00a.png| | + | | style="padding:10px;"| [[Image:Review_239195285364_1856_NewCircumscribedTriangle00a.png|260px|]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||