m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 818140696 to Gonzalez-Sanmamed et al 2020a) |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | <span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>[[#article_en|Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)]]</span> | |

| + | |||

| + | [[Media:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170.pdf|<span style="color:#0645AD; font-weight: bold">Download the PDF version</span>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Resumen == | ||

| + | |||

| + | This study analyses the extent to which university faculty use the technological resources that make up their Learning Ecologies to promote their professional development as educators. The interest of this research lies on the growing impact of Learning Ecologies as a framework to examine the multiple learning opportunities provided by a complex digital landscape. Global data referred to the use of technological resources grouped in three dimensions (information access, search and management resources, creation and content editing resources, and interaction and communication resources) has been identified. In addition, the influence of different variables such as gender, age, years of teaching experience and the field of knowledge were also examined. The study was conducted using a survey-based quantitative methodology. The sample consisted of 1,652 faculty belonging to 50 Spanish universities. To respond to the objectives of the study, descriptive and inferential analyses (ANOVA) were carried out. On the one hand, a moderate use of technological resources for professional development was noted while on the other hand, significant differences were observed on all variables analyzed. The results suggest a need to promote, both at the individual and institutional levels, more enriched Learning Ecologies, in such a way that each professor can harness the learning opportunities afforded by the networked society. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Resumen= | ||

| + | |||

| + | En este estudio se analiza en qué medida el profesorado universitario utiliza los recursos tecnológicos que configuran sus Ecologías de Aprendizaje para propiciar su desarrollo profesional como docentes. El interés de esta investigación radica en el creciente impacto del constructo de las Ecologías de Aprendizaje como marco para examinar e interpretar las múltiples oportunidades de aprendizaje que ofrece el complejo panorama digital actual. Además de identificar los datos globales referidos al uso de los recursos tecnológicos agrupados en tres dimensiones (recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información, recursos de creación y edición de contenido, y recursos de interacción y comunicación), también se examina la influencia de diferentes variables como el género, la edad, los años de experiencia docente y la rama de conocimiento. La metodología empleada ha sido de corte cuantitativo a través de encuesta. La muestra está compuesta por 1.652 profesores pertenecientes a 50 universidades españolas. Para dar respuesta al objetivo del estudio se llevaron a cabo análisis descriptivos e inferenciales (ANOVA). Se constata un empleo moderado de los recursos tecnológicos para el desarrollo profesional y, además, se observan diferencias significativas en función de las variables analizadas. Los resultados alertan de la necesidad de fomentar, tanto a nivel individual como institucional, Ecologías de Aprendizaje más enriquecidas, de manera que cada docente pueda aprovechar mejor las posibilidades de aprendizaje que ofrece la sociedad en red. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Continuing education, teacher education, professional development, university teachers, higher education, learning ecologies, technological resources, informal learning | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Palabras clave==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Formación permanente, formación del profesorado, desarrollo profesional, profesorado universitario, educación superior, ecologías de aprendizaje, recursos tecnológicos, aprendizaje informal | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introduction and state of the art== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The unrelenting explosion and expansion of knowledge, along with its obsolescence, generate great instability both at an individual and institutional levels, demanding the need for lifelong learning as a basic requirement for personal and professional development. But, in addition, learning has undergone a metamorphosis (González-Sanmamed, Sangrà, Souto-Seijo, & Estévez, 2018) as new formats have been fostered, time and space have been extended, and informal and non-formal models of knowledge acquisition have been strengthened. Thus, learning is characterized as ubiquitous (Díez-Gutiérrez & Díaz-Nafría, 2018), invisible (Cobo & Moravec, 2011), connected (Siemens, 2007) or rhizomatic (Cormier, 2008). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this attempt to answer questions about what, how, when and where learning takes place in a networked society, the concept of Learning Ecologies (LE) emerges as a perspective to analyze and arbitrate proposals that account for the open, dynamic and complex mechanisms from which knowledge is constructed and shared. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several authors have upheld the relevance of LE as a construct that enables the appreciation and promotion of the broad and diverse learning opportunities offered by the current context (Looi, 2001; Barron, 2006; Jackson, 2013; Sangrà, González-Sanmamed, & Guitert, 2013; Maina & García, 2016). Specifically, Jackson (2013: 7) states that LE “understand the processes and variety of contexts and interactions that provide individuals with opportunities and resources to learn, to develop and to achieve”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The recent review by Sangrá, Raffaghelli and Guitert-Catasús (2019) reveals the interest aroused by this concept and the studies being conducted with various groups to reveal how they benefit from, and also how they could promote, their LE. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In particular, analyses have been developed to explore in-service teachers' LE and their links with learning processes and teachers’ professional development (Sangrá, Guitert, Pérez-Mateo, & Ernest, 2011; Sangrà, González-Sanmamed, & Guitert, 2013; González-Sanmamed, Santos, & Muñoz-Carril, 2016; Ranieri, Giampaolo, & Bruni, 2019; Van-den-Beemt & Diiepstraten, 2016). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The confluence of both lines of reflection and inquiry is promising, especially when considering the assumption of professional development as a process of continuous learning, in which each teacher tries to improve their own training, taking advantage of the resources available through various mechanisms and contexts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The demand for a teaching staff that is up to date, with the skills and knowledge that guarantee their adequate performance, and with the commitment required for the task of training future generations, takes on special relevance in the field of higher education. The professional development of university professors is a key factor in guaranteeing quality higher education (Darling-Hammond & Richardson, 2009; Inamorato, Gausas, Mackeviciute, Jotautyte, & Martinaitis, 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Various studies have identified the characteristics, conditions and models of professional development for university faculty, and have also assessed the improvements these provide (Gast, Schildkamp & Van-der-Veen, 2017; Van Waes, De-Maeyer, Moolenaar, Van-Petegem, & Van-den-Bossche, 2018; Jaramillo-Baquerizo, Valcke, & Vanderlinde, 2019). The expansion of technology is generating new formats for professional development (Parsons & al., 2019) by facilitating learning anytime, anywhere (Trust, Krutka, & Carpenter, 2016). Specifically, university professors have begun to create opportunities for their own professional development using different resources such as video tutorials or social networks (Brill & Park, 2011; Seaman & Tinti-Kane, 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | These and other studies highlight the relevance of technological resources in the learning and professional development processes of university professors. The importance of resources has been recognized by various authors (Barron, 2006; Jackson, 2013; González-Sanmamed, Muñoz-Carril, & Santos-Caamaño, 2019) as one of the components of LE which, together with contexts, actions and relationships, represent the pillars upon which individuals can articulate, manage and promote their own LE. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As He and Li (2019) noted, learning is becoming increasingly self-directed and informal with the support of technology, hence the need to explore the resources used by faculty to foster their professional development from an integrative vision provided by LE. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the one hand, we have to assume the importance and control of educators to direct their own learning according to their needs, interests and potentialities, determining aspects of professional development (Muijs, Day, Harris, & Lindsay, 2004), but we also have to take into account how resources influence or may influence the development of the other components of LE (fostering actions, stimulating relationships, generating contexts, etc.) that will contribute to the development of personalized learning and professional development modalities (Yurkofsky, Blum-Smith, & Brennan, 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Materials and methods== | ||

| + | |||

| + | This study is part of a wider project that analyses the LE of university professors and their impact on learning processes and professional development related to teaching. Specifically, the purpose of this study was to identify the technological tools that make up the LE of university professors, and to assess the extent to which they are used to promote their professional development. The following hypotheses were put forward: | ||

| + | |||

| + | The demand for a teaching staff that is up to date, with the skills and knowledge that guarantee their adequate performance, and with the commitment required for the task of training future generations, takes on special relevance in the field of higher education. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1) Gender is associated with significant differences in the use of technological resources for the professional development of university professors from the LE perspective. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2) Age is a significant factor in the use of technological tools for the professional development of university professors. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3) Experience generates significant differences in the use of technological tools for the professional development of university professors from the LE viewpoint. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4) The professor's field of knowledge leads to significant differences in the use of technological tools for the professional development of university professors within the LE framework. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A descriptive methodology with a cross-sectional design was applied using a survey-based method. The data were collected through a questionnaire designed ad hoc from a systematic review of the literature on LE. To establish the validity of the content, the initial instrument was submitted to expert judgement. Nine professionals with training on the study subject (LE) and educational research methodology participated in the validation process, all of them with more than 12 years of professional experience at the university level. Based on their assessments, the first version was reworked and then a pilot test was conducted on 210 subjects to determine the reliability of the questionnaire. After verifying adequate psychometric levels and reviewing some grammatical aspects, the final version was created in digital format (Google Forms) and administered online. The application was open for 5 months. Different institutional managers collaborated and distributed the instrument by e-mail. A presentation was included explaining the objective of the study, framed within its research project, and providing anonymity and confidentiality guarantees. All questions had to be answered and the average response time was around 12 minutes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The complete questionnaire included seven scales. The first four evaluated constructs within the personal dimension of LE and the next three delved into the experiential dimension of the Ecologies (González-Sanmamed, Muñoz-Carril, & Santos-Caamaño, 2019). To carry out this study, one of the scales included in the experiential dimension was used, namely the Resource Scale. Its design was based on the typology of digital tools proposed by Adell and Castañeda (2010), Castañeda and Adell (2013), Kop (2011), as well as Dabbagh and Kitsantas (2012). | ||

| + | |||

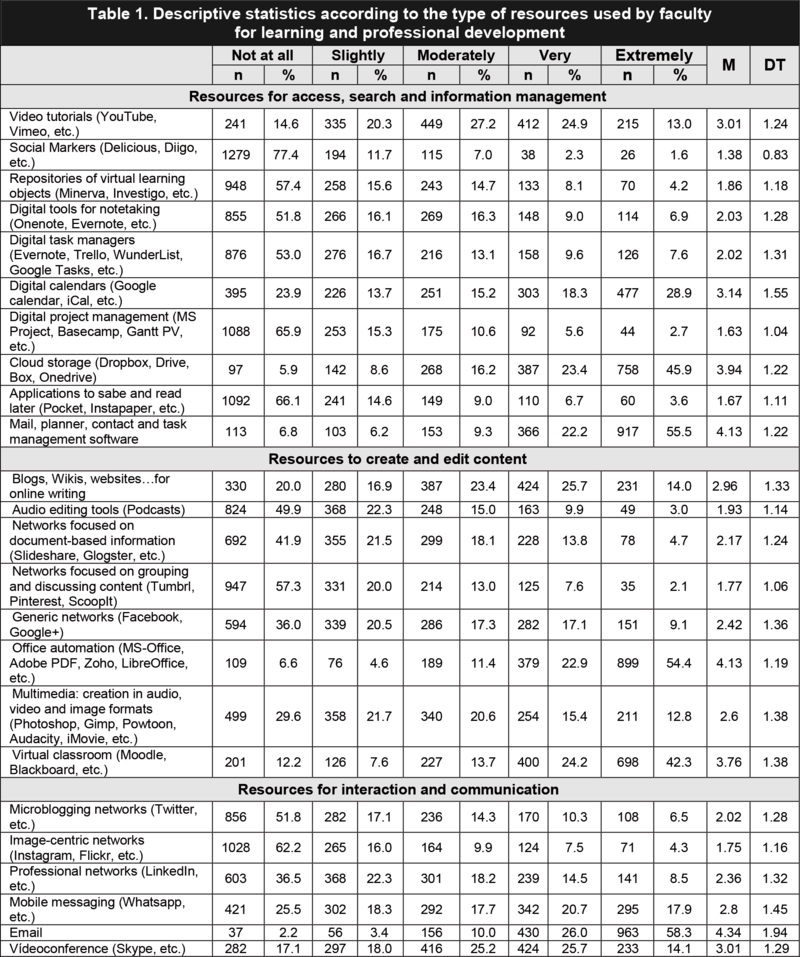

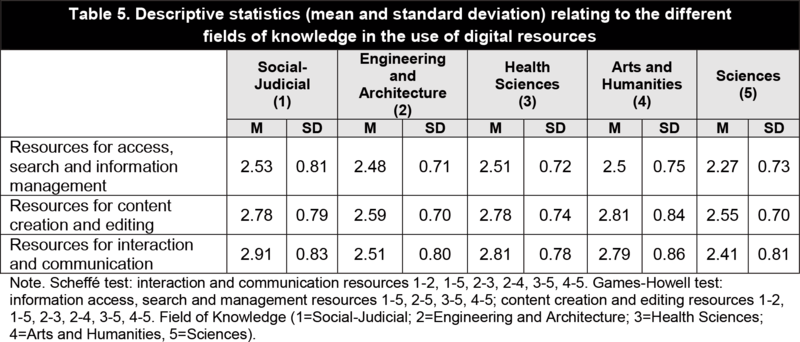

| + | The Resource Scale is comprised of 24 items (Table 1), with a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), distributed into three factors. The first of these, with 10 items, includes the “resources for access, search and information management”; the second factor includes the “resources for creating and editing content”, with eight items; and finally, the third factor, made up of six items, groups the “interaction and communication resources”. Once the questionnaire had been administered and the criteria of reliability had been met once again, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was calculated, both globally (α=.90) and for each of the dimensions making up the questionnaire: resources for access, search and management of information (α=.82), content creation and editing resources (α=.75), as well as interaction and communication resources (α=.75). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170-e898fc81-f67d-4e54-b947-8724f3d9644d-ueng-01-01.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/bc6b60cd-46dd-4d11-bb20-8cad35ee1168/image/e898fc81-f67d-4e54-b947-8724f3d9644d-ueng-01-01.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Non-probability, convenience sampling was used. The sample was comprised of 1,652 university professors belonging to 50 Spanish universities, 50.5% male and 49.5% female. In terms of age, 23.8% were under 40 years of age; 33.1% were between 41 and 50 years of age, and 43.2% were over 51 years of age. 33.4% had less than 10 years of teaching experience; 26.3% had between 11 and 20 years, and 40.3% had more than 20 years of experience. The distribution by field of knowledge was the following: 28% belonged to the Social-Judicial field, 21.4% to the field of Engineering and Architecture, 25.2% to Health Sciences, 13.8% to Arts and Humanities and, finally, 11.1% to the field of Sciences. Data was analyzed with the IBM SPSS (v.25) software. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Analysis and results== | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Table 1, through the descriptive statistics of each item, organized into the three dimensions considered, it is possible to appreciate the tools that are used to a greater or lesser degree. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170-2ebdc681-b511-46fc-910b-f319f2de0d3c-ueng-01-02.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/bc6b60cd-46dd-4d11-bb20-8cad35ee1168/image/2ebdc681-b511-46fc-910b-f319f2de0d3c-ueng-01-02.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

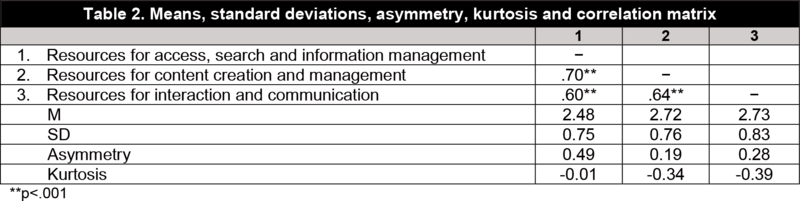

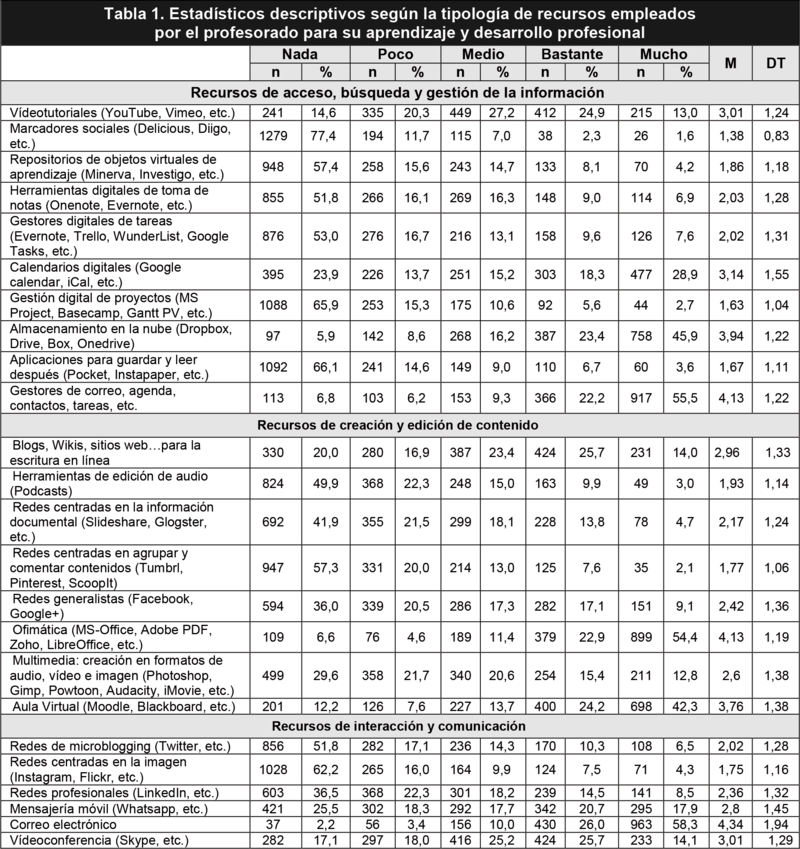

| + | Table 2 provides the means, standard deviations, asymmetry, kurtosis, as well as the Pearson correlation coefficients for the dependent variables used in this study. The normal distribution of the variables was analyzed based on the criteria adopted by Finney and DiStefano (2006), who indicate maximum values of two and seven for asymmetry and kurtosis, respectively. It can be concluded that the variables included in this study exhibit normal distributions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170-2e081719-30a1-42e8-97ff-a0bfb69beac1-ueng-01-03.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/bc6b60cd-46dd-4d11-bb20-8cad35ee1168/image/2e081719-30a1-42e8-97ff-a0bfb69beac1-ueng-01-03.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In terms of correlations, there is a significant and positive relationship between the use of resources for access, search and management of information and resources for content creation and management (r=.70; p<.001); furthermore, there is also the relationship between the use of resources for content creation and management and resources for interaction and communication (r=.64; p<.001), and finally the one between the use of resources for creation and management and resources for interaction and communication (r=.60; p<.001). | ||

| + | |||

| + | First, taking gender as an independent variable, and the three types of resources as dependent variables, the ANOVA results show that there are statistically significant differences with a small effect size in the use of information access, search and management resources [F<sub id="subscript-5">(1.1650)</sub>=3.962, p<.05; η<sub id="subscript-6">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-5">2</sup>=.002], as well as in the use of resources to create and edit content [F<sub id="subscript-7">(1.1650)</sub>=38.917, p<.001; η<sub id="subscript-8">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-6">2</sup>=.02], and finally in the use of interaction and communication resources [F<sub id="subscript-9">(1.1650)</sub>=33.584, p<.001; η<sub id="subscript-10">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-7">2</sup>=.02] according to gender, with female participants using the three types of resources at a greater degree. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170-ce876b28-2ae5-4328-a108-5cdfbd48b3df-ueng-01-04.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/bc6b60cd-46dd-4d11-bb20-8cad35ee1168/image/ce876b28-2ae5-4328-a108-5cdfbd48b3df-ueng-01-04.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

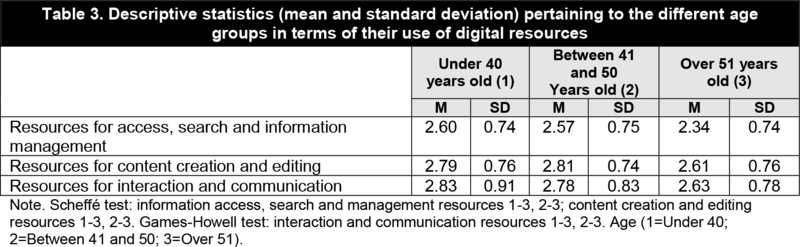

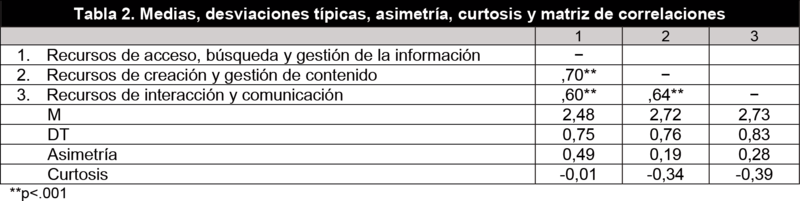

| + | Second, an ANOVA was performed considering age as an independent variable (1=under 40 years; 2=between 41 and 50 years; and 3=over 50 years) and the use of the three types of resources as dependent variables. In the case of interaction and communication resources, the robust Brown-Forsythe (F*) tests were used, followed by Games-Howell post-hoc tests, not assuming equal variances. The results show statistically significant differences with a small effect size on the use of information access, search and management resources [F<sub id="subscript-11">(2.1649)</sub>=20.689, p<.001; η<sub id="subscript-12">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-8">2</sup> =.02], in the use of resources to create and edit content [F<sub id="subscript-13">(2.1649)</sub>=12.243, p<.001; η<sub id="subscript-14">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-9">2</sup>=.01 and in the use of interaction and communication resources [F*<sub id="subscript-15">(2.1313)</sub>=9.032, p<.001; η<sub id="subscript-16">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-10">2</sup>=.01] depending on age. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Specifically, there are differences in the use of the three types of resources considered between professors who are under 40 and those who are over 51, and between those who are between 41 and 50 and those who are over 51. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Results show the same trend: greater use of digital resources for professional development by the youngest group of professors, followed by the group between 41 and 50 years of age, and a distinctly lower use by the group over 51 years of age (Table 3). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170-e9f7319d-f677-49ce-8597-1898c1832124-ueng-01-05.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/bc6b60cd-46dd-4d11-bb20-8cad35ee1168/image/e9f7319d-f677-49ce-8597-1898c1832124-ueng-01-05.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

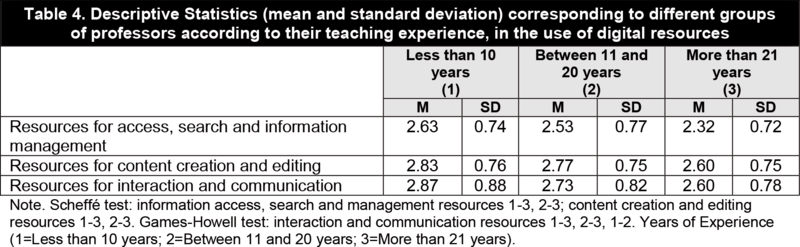

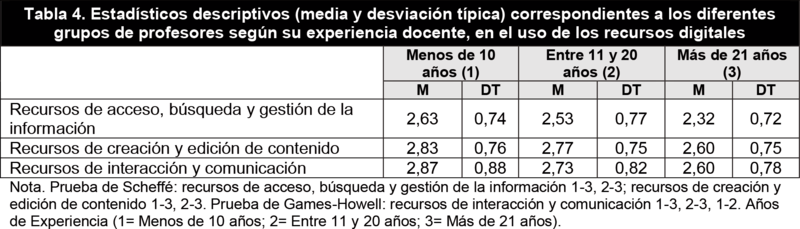

| + | Third, an ANOVA was performed taking the years of experience as an independent variable (1=less than 10 years, 2=between 11 and 20 years, 3=more than 21 years) and the use of the three types of digital resources as dependent variables. In the case of interaction and communication resources, the robust Brown-Forsythe (F*) tests were used, followed by Games-Howell post-hoc tests, given that the assumption of variance homogeneity was not met. The results indicated that there are statistically significant differences (with a small effect size) in the use of access, search and management resources [F<sub id="s-1404f993807a">(2.1649)</sub>=26.774, p<.001; η<sub id="s-224188c0e06b">p</sub> <sup id="s-fa277d892707">2</sup>=.03], as well as in the use of resources for creating and editing content [F<sub id="s-346d3260c348">(2.1649)</sub>=15.39, p<.001; η<sub id="s-b377d92ef9d6">p</sub> <sup id="s-28fd20f30e34">2</sup>=.02], and in the use of interaction and communication resources [F*<sub id="s-146efa7acfce">(2.1516)</sub>=15.86 , p<.001; η<sub id="s-4ed5ceaee54a">p</sub> <sup id="s-f7620e7ef8f8">2</sup>=.02], depending on the years of experience. Although the effect is small in all three cases, there are differences in the use of access, search and information management resources between professors with less than 10 years of experience and those with more than 21 years of experience, and between the group with between 11 and 20 years of experience and the group with more than 21 years of experience. The trend in all three cases is that the use of digital resources to foster professional development decreases as teaching experience increases. | ||

| + | |||

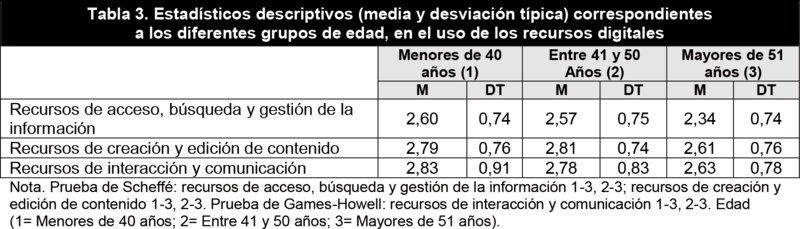

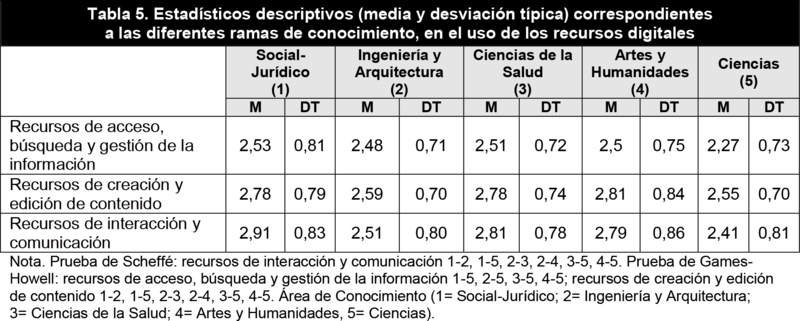

| + | Finally, a final ANOVA was carried out taking the field of knowledge as an independent variable (1=Social-Judicial, 2=Engineering-Architecture, 3=Health Sciences, 4=Arts-Humanities, 5=Sciences), and the use of interaction and communication resources as a dependent variable. At the same time, the other two dependent variables (information access, search and management resources, as well as the use of interaction and communication resources) were taken into account. At the same time, since the other two dependent variables (information access, search and management resources, and content creation and editing resources) did not meet the homoscedasticity assumption, the robust Brown-Forsythe (F*) tests were used, followed by post-hoc Games-Howell tests. The results show statistically significant differences with a small effect size on the use of information access, search and management resources [F*<sub id="s-3818d29b444e">(4.1384)</sub>=4.29, p<.01; η<sub id="s-f3413536b6ee">p</sub> <sup id="s-59fea4401d07">2</sup>=.01], in the use of content creation and editing resources [F*<sub id="s-8e8b250e9cd9">(4.1336)</sub>=7.29, p<.001; η<sub id="s-9c24ed4444a5">p</sub> <sup id="s-fe28a0686954">2</sup>=.017], and in the use of interaction and communication resources [F<sub id="s-380bc52a78bc">(4.1647)</sub>=19.92 , p<.001; η<sub id="s-c0ed3384cdd0">p</sub> <sup id="s-0cdfd7e02632">2</sup>=.046,] based on years of experience (Table 5). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although the size of the effect was small, significant differences were found in the use of access, search and information management resources between the teaching staff in the science field and those in the other fields, with this group displaying the lowest rates of use of this type of resources. In this case, the teaching staff of the Social-Judicial area exhibits the highest use values. In terms of the use of resources of content creation and editing, the Arts and Humanities group exhibits the highest usage indexes, followed by the Health Sciences faculty and those in the Social-Judicial field; the groups that use these resources to a lesser extent are those in Engineering and Architecture, and Science. As for interaction and communication resources, the faculty of the Social-Judicial field stands out with the highest rates of use of this type of tools, followed by the Health Sciences and the Arts and Humanities groups, with the Engineering and Architecture as well as the Science faculties using these resources the least. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 5 also shows that the trend towards the use of resources for creation and editing, and for interaction and communication is greater than the use of resources for access, search and management of information in all the fields of knowledge. The scarce use of digital tools by Science teaching staff as compared to professors in the rest of the fields of knowledge stands out. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Discussion and conclusions == | ||

| + | |||

| + | First of all, it should be noted that this study is part of an emerging line of research that still needs to be conceptually strengthened and empirically explored. In addition, it could be regarded as pioneering, since the scarce work available on professional development processes within the framework of LE has been performed with educators at non-university levels. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A global analysis of the results enables a glimpse into the most used resources for professional development: email, office automation, mail managers, planner, virtual classroom, cloud storage, digital calendars, and video tutorials. These are all tools used daily in teaching and, perhaps, the most accessible and manageable tools to promote update and continuous improvement processes. Each professor includes some of the tools in his/her Learning Ecology through diverse experiences, interactions and contexts along his/her life journey, turning them into resources for professional development to the extent to which they are activated consciously and autonomously to foster localized and personalized learning. In fact, research carried out on digital competence (Durán, Prendes, & Gutiérrez, 2019) or studies on TPACK (Jaipal & al., 2018) in higher education teaching staff confirm the need to strengthen the integration of technology at the university level, and to reinforce the technological training of faculty. Responsibility lies with each professor, and also with the institutions themselves, to facilitate access to and promote the use of technological resources that enable the configuration of an enriched ecology from which each professor could guide his or her own professional development. The analyses carried out indicate that all the hypotheses raised have been met. With regard to gender, it must be noted that this is a controversial variable given the discrepancies in the results of previous research concerning its impact on the use of technology and on teaching professional development. In order to assess the data in this study, which reveals that females account for the majority use of the three types of resources for their professional development, it is important to point out that female university professors are more interested in carrying out self-actualization training activities than male professors (Caballero, 2013). However, it would also be advisable to study the influence of other variables such as the perception of self-efficacy, anxiety, attitude or intrinsic motivation towards the use of technology (Drent & Meelissen, 2008). | ||

| + | |||

| + | With regard to results in terms of the fields of knowledge, it is worth noting that Science professors, followed by Engineering and Architecture professors, are the ones who use digital resources the least to develop professionally. These data can be evaluated in light of the study carried out by Cabero, Llorente and Marín (2010). In addition, the scarce use of Interaction and Communication resources among Science as well as Engineering and Architecture professors may suggest a preference for individual rather than cooperative work (Caballero, 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In general, the results obtained reflect a discrete use of technological resources for professional development, revealing some significant limitations in the configuration of university professors’ LE. The implications of these results have to be assessed from a three-fold perspective: they warn of the need to increase the range of resources available for teacher training, warn of the desirability of broadening the formats for professors’ professional development, and encourage the establishment of mechanisms that contribute to reinforcing LE in order to make them more prosperous. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The impact of these implications is twofold. On the one hand, at the professional level, each professor must be aware of the components that make up his or her LE, since this would mean taking control of their learning process according to individual needs, interests and opportunities (Maina & García, 2016). On the other hand, at an institutional level, the recognition of the importance of LE for professors’ optimal and fruitful professional development would be the starting point for improving the training offering by universities through the design of continuous faculty training plans with more personalized, open and flexible itineraries. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, although the study has focused on the analysis of digital resources, recognized as essential components of the experiential dimension of LE (González-Sanmamed, Muñoz-Carril, & Santos-Caamaño, 2019), it is essential to take into account their interdependence with the other components of LE (Relationships, Contexts and Actions). Thus, resources can facilitate collaboration between professors, evidencing their potential to avoid isolation and to promote success in professional development, for example, through social networks or learning communities (Lozano, Iglesias, & Martinez, 2014). On the other hand, resources not only favor, but also expand learning contexts, in a continuum ranging from most formal to informal settings (Sangrá & al., 2011). Finally, digital resources reduce spatial-temporal limitations, offering new and timely ways to carry out training actions in todays’ complex scenario. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ol><li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | AdellJ, CastañedaL J, . 2010.[https://bit.ly/2WjjIw3 Los entornos personales de aprendizaje (PLEs): Una nueva manera de entender el aprendizaje]. In: RoigR., FiroucciM., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Claves para la investigación en innovación y calidad educativas. La integración de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación en las aulas&author=Roig&publication_year= Claves para la investigación en innovación y calidad educativas. La integración de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación en las aulas].Alcoy: Marfil-RomaTRE Universita degli studi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | BarronB, . 2006.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective&author=Barron&publication_year= Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective].Human Development 49:193-224 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | BrillJ, ParkY, . 2011.[https://bit.ly/2HUNw8Q Evaluating online tutorials for university faculty, staff, and students: The contribution of just-in-time online resources to learning and performance].International Journal on E-learning 10(1):5-26 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CaballeroK, . 2013.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La formación del profesorado universitario y su influencia en el desarrollo de la actividad profesional&author=Caballero&publication_year= La formación del profesorado universitario y su influencia en el desarrollo de la actividad profesional].Revista de Docencia Universitaria 11(2):391 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CaberoJ, LlorenteM C, MarínV, . 2010.[https://bit.ly/2M842rj Hacia el diseño de un instrumento de diagnóstico de ‘competencias tecnológicas del profesorado’ universitario].Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 52(7):1-12 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CastañedaL, AdellJ, . 2013. , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Entornos personales de aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en red&author=&publication_year= Entornos personales de aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en red].Alcoy: Marfil. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CoboC, MoravecJ, . 2011.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Aprendizaje invisible. Hacia una nueva ecología de la educación&author=&publication_year= Aprendizaje invisible. Hacia una nueva ecología de la educación]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CohenJ, . 1988.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences&author=&publication_year= Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences]. Hillsdate, NJ: LEA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CormierD, . 2008.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Rhizomatic education: Community as curriculum&author=Cormier&publication_year= Rhizomatic education: Community as curriculum].In¬novate: Journal of Online Education (5)4 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | DabbaghN, KitsantasA, . 2012.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Personal learning environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning&author=Dabbagh&publication_year= Personal learning environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning].The Internet and Higher Education 15(1):3-8 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Darling-HammondL, RichardsonN, . 2009.[https://bit.ly/2YPSvyi Research review/teacher learning: What matters?]Educational Leadership 66(5):46-53 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Díez-GutiérrezE, Díaz-NafríaJ M, . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Ubiquitous learning ecologies for a critical cybercitizenship. [Ecologías de aprendizaje ubicuo para la ciberciudadanía crítica]&author=Díez-Gutiérrez&publication_year= Ubiquitous learning ecologies for a critical cybercitizenship. [Ecologías de aprendizaje ubicuo para la ciberciudadanía crítica]]Comunicar 26:9-58 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | DíazW B, . 2015. , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Formación del profesorado universitario, evaluación de la actividad docente y promoción profesional&author=&publication_year= Formación del profesorado universitario, evaluación de la actividad docente y promoción profesional].(Tesis Doctoral). Madrid: UNED. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | DrentM, MeelissenM, . 2008.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Which factors obstruct or stimulate teacher educators to use ICT innovatively?&author=Drent&publication_year= Which factors obstruct or stimulate teacher educators to use ICT innovatively?]Computers & Education 51(1):187-199 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | DuránM, PrendesM, GutiérrezI, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Certificación de la competencia digital docente: Propuesta para el profesorado universitario&author=Durán&publication_year= Certificación de la competencia digital docente: Propuesta para el profesorado universitario].Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 22(1):187-205 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | FinneyS J, DistefanoC, . 2006.[https://bit.ly/2YB0YsZ Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling]. In: HancockG.R., MuellerR.O., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Structural equation modeling: A second course&author=Hancock&publication_year= Structural equation modeling: A second course].Greenwich: Information Age Publishing. 269-314 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | GastI, SchildkampK, Van-Der-VeenJ T, . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Team-based professional development interventions in higher education: A systematic review&author=Gast&publication_year= Team-based professional development interventions in higher education: A systematic review].Review of Educational Research 87(4):736-767 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | González-SanmamedM, Muñoz-CarrilP C, Santos-CaamañoF J, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Key components of learning ecologies: A Delphi assessment&author=González-Sanmamed&publication_year= Key components of learning ecologies: A Delphi assessment].British Journal of Educational Technology 50(4):1639-1655 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | González-SanmamedM, SangráA, Souto-SeijoA, EstévezI, . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Ecologías de aprendizaje en la era digital: Desafíos para la educación superior&author=González-Sanmamed&publication_year= Ecologías de aprendizaje en la era digital: Desafíos para la educación superior].Publicaciones 48:11-38 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | González-SanmamedM, SantosF, Muñoz-CarrilP C, . 2016.[https://bit.ly/2K4RiPS Teacher education & profesional development: A learning perspective].Lifewide Magazine 16:13-16 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | HeT, LiS, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=A comparative study of digital informal learning: The effects of digital competence and technology expectancy&author=He&publication_year= A comparative study of digital informal learning: The effects of digital competence and technology expectancy].British Journal of Educational Technology 4(50):1-15 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | InamoratoA, GausasS, MackeviciuteR, JotautyteA, MartinaitisZ, . 2019. , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Innovating professional development in higher education: An analysis of practices innovating professional development in higher education&author=&publication_year= Innovating professional development in higher education: An analysis of practices innovating professional development in higher education].Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | JaipalK, FiggC, CollierD, GallagherT, WintersK L, CiampaK, . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Developing TPACK of university faculty through technology leadership roles&author=Jaipal&publication_year= Developing TPACK of university faculty through technology leadership roles].Italian Journal of Educational Technology 26(1):39-55 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | JacksonN, . 2013..N. Jackson, .B. Cooper, eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Lifewide learning, education & personal development&author=.&publication_year= Lifewide learning, education & personal development].1-21The concept of learning ecologies | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jaramillo-BaquerizoC, ValckeM, VanderlindeR, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Professional development initiatives for university teachers: Variables that influence the transfer of learning to the workplace&author=Jaramillo-Baquerizo&publication_year= Professional development initiatives for university teachers: Variables that influence the transfer of learning to the workplace].Innovations in Education and Teaching International 59(3):352-362 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | LooiC K, . 2001.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Enhancing learning ecology on the Internet&author=Looi&publication_year= Enhancing learning ecology on the Internet].Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 17(1):13-20 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | LozanoI, IglesiasM J, MartínezM A, . 2014.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Las oportunidades de las académicas en el desarrollo profesional docente universitario: un estudio cualitativo&author=Lozano&publication_year= Las oportunidades de las académicas en el desarrollo profesional docente universitario: un estudio cualitativo].Educación XX1 17(1):159-182 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | MainaM, GarcíaI, . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Articulating personal pedagogies through learning ecologies&author=Maina&publication_year= Articulating personal pedagogies through learning ecologies]. In: GrosB., KindshukM.M., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The future of ubiquitous learning: Learning designs for emerging pedagogies&author=Gros&publication_year= The future of ubiquitous learning: Learning designs for emerging pedagogies].Berlin: Springer. 73-94 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | KopR, . 2011.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course&author=Kop&publication_year= The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course].The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 12(3):19-38 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | MuijsD, DayC, HarrisA, LindsayG, . 2004.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Evaluating CPD: An overview&author=Muijs&publication_year= Evaluating CPD: An overview]. In: DayC., ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=International Handbook on the Continuing Professional Development of teachers&author=Day&publication_year= International Handbook on the Continuing Professional Development of teachers].Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education. 291-319 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ParsonsS A, HutchisonA C, HallL A, WardA, IvesS T, BruyningA, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=US teachers’ perceptions of online professional development&author=Parsons&publication_year= US teachers’ perceptions of online professional development].Teaching and Teacher Education 82:33-42 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | RanieriM, GiampaoloM, BruniI, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Exploring educators’ professional learning ecologies in a blended learning environment&author=Ranieri&publication_year= Exploring educators’ professional learning ecologies in a blended learning environment].British Journal of Educational Technology1-14 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SangràA, González-SanmamedM, GuitertM, . 2013.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Learning ecologies: Informal professional development opportunities for teachers&author=Sangrà&publication_year= Learning ecologies: Informal professional development opportunities for teachers]. In: TanD., FangL., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Proceedings of the IEEE 63rd Annual Conference International Council for Educational Media&author=Tan&publication_year= Proceedings of the IEEE 63rd Annual Conference International Council for Educational Media].Singapore: ICEM-CIME. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SangráA, GuitertM, Pérez-MateoM, ErnestP, . 2011.[https://bit.ly/30NdaF2 Learning and Sustainability. The New Ecosystem of Innovation and Knowledge]. In: PaulsenM.F., SzücsA., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Lifelong lear¬ning ecologies and teachers’ professional development: A roadmap for research&author=Paulsen&publication_year= Lifelong lear¬ning ecologies and teachers’ professional development: A roadmap for research].Dublin: Annual Conference. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SangráA, RaffaghelliJ E, Guitert-CatasúsM, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Learning ecologies through a lens: Ontological, methodological and applicative issues. A systematic review of the literature&author=Sangrá&publication_year= Learning ecologies through a lens: Ontological, methodological and applicative issues. A systematic review of the literature].British Journal of Educational Technology 50(4):1-20 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SeamanJ, Tinti-KaneH, . 2013.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Social media for teaching and learning&author=&publication_year= Social media for teaching and learning]. London: Pearson Learning Systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SiemensG, . 2007.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Connectivism: Creating a learning ecology in distributed environments&author=Siemens&publication_year= Connectivism: Creating a learning ecology in distributed environments].Didatics of microlearning: Concepts, discourses, and examples. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | TrustT, KrutkaD G, CarpenterJ P, . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Together we are better: Professional learning networks for teachers&author=Trust&publication_year= Together we are better: Professional learning networks for teachers].Computers & Education 102:15-34 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Van-Den-BeemtA, DiepstratenI, . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Teacher perspectives on ICT: A learning ecology approach&author=Van-Den-Beemt&publication_year= Teacher perspectives on ICT: A learning ecology approach].Computers & Education 92:161-170 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Van-WaesS, De-MaeyerS, MoolenaarN M, Van-PetegemP, Van-Den-BosscheP, . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Strengthening networks: A social network intervention among higher education teachers&author=Van-Waes&publication_year= Strengthening networks: A social network intervention among higher education teachers].Learning and Instruction 53:34-49 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | VeraJ A, TorresL E, MartínezE E, . 2014.[https://bit.ly/2X79f3V Evaluación de competencias básicas en TIC en docentes de educación superior en México].Pixel-Bit 44:143-155 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | YurkofskyM M, Blum-SmithS, BrennanK, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Expanding outcomes: Exploring varied conceptions of teacher learning in an online professional development experience&author=Yurkofsky&publication_year= Expanding outcomes: Exploring varied conceptions of teacher learning in an online professional development experience].Teaching and Teacher Education 82:1-13 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_en"></span>[[#article_es|Click to see the English version (EN)]]</span> | <span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_en"></span>[[#article_es|Click to see the English version (EN)]]</span> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | [[Media:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170_ov.pdf|<span style="color:#0645AD; font-weight: bold">Descarga aquí la versión PDF</span>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Resumen == | ||

| + | |||

| + | En este estudio se analiza en qué medida el profesorado universitario utiliza los recursos tecnológicos que configuran sus Ecologías de Aprendizaje para propiciar su desarrollo profesional como docentes. El interés de esta investigación radica en el creciente impacto del constructo de las Ecologías de Aprendizaje como marco para examinar e interpretar las múltiples oportunidades de aprendizaje que ofrece el complejo panorama digital actual. Además de identificar los datos globales referidos al uso de los recursos tecnológicos agrupados en tres dimensiones (recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información, recursos de creación y edición de contenido, y recursos de interacción y comunicación), también se examina la influencia de diferentes variables como el género, la edad, los años de experiencia docente y la rama de conocimiento. La metodología empleada ha sido de corte cuantitativo a través de encuesta. La muestra está compuesta por 1.652 profesores pertenecientes a 50 universidades españolas. Para dar respuesta al objetivo del estudio se llevaron a cabo análisis descriptivos e inferenciales (ANOVA). Se constata un empleo moderado de los recursos tecnológicos para el desarrollo profesional y, además, se observan diferencias significativas en función de las variables analizadas. Los resultados alertan de la necesidad de fomentar, tanto a nivel individual como institucional, Ecologías de Aprendizaje más enriquecidas, de manera que cada docente pueda aprovechar mejor las posibilidades de aprendizaje que ofrece la sociedad en red. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =ABSTRACT= | ||

| + | |||

| + | This study analyses the extent to which faculty use the technological resources that make up their Learning Ecologies to encourage their teacher professional development. The interest of this research is the growing impact of Learning Ecologies as a framework to examine the multiple learning opportunities provided by the complex digital landscape. Global data referred to the use of technological resources grouped in three dimensions (Access, Search and Information Management resources, Creation and Content Editing resources, and Interaction and Communication resources) has been identified. In addition, the influence of different variables such as gender, age, years of teaching experience and the branch of knowledge were also examined. The methodology used has been quantitative through a survey. The sample consisted of 1,652 faculty belonging to 50 Spanish universities. To meet the aim of the study, descriptive and inferential analysis (ANOVA) were carried out. On the one hand, it is noted a moderate use of technological resources for professional development and, on the other hand, significant differences are observed on all variables analysed. The results warn of the need to promote, both at individual and institutional level, more enriched Learning Ecologies, in such a way that each teacher can take better advantage of the learning opportunities, provided by the networked society. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Palabras clave==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Formación permanente, formación del profesorado, desarrollo profesional, profesorado universitario, educación superior, ecologías de aprendizaje, recursos tecnológicos, aprendizaje informal | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Continuing education, teacher education, professional development, university teachers, higher education, learning ecologies, technological resources, informal learning | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introducción y estado de la cuestión== | ||

| + | |||

| + | La imparable explosión y expansión del conocimiento, así como su obsolescencia, genera una gran inestabilidad tanto a nivel particular como institucional, y reclama la necesidad de un aprendizaje a lo largo y ancho de la vida como requisito básico para el desarrollo personal y profesional. Pero, además, se ha producido una metamorfosis del aprendizaje (González-Sanmamed, Sangrà, Souto-Seijo, & Estévez, 2018), al propiciarse nuevos formatos, ampliarse los tiempos y los espacios, y potenciarse los modelos informales y no formales de adquisición del saber. Así, el aprendizaje se caracteriza como ubicuo (Díez-Gutiérrez & Díaz-Nafría, 2018), invisible (Cobo & Moravec, 2011), conectado (Siemens, 2007) o rizomático (Cormier, 2008). | ||

| + | |||

| + | En este esfuerzo por dar respuesta a las preguntas acerca de qué, cómo, cuándo y dónde, acontece el aprendizaje en la sociedad en red, surge el concepto de Ecologías de Aprendizaje (EA) como perspectiva para analizar y arbitrar propuestas que tengan en cuenta los mecanismos abiertos, dinámicos y complejos desde los que se construye y se comparte el conocimiento. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Diversos autores han defendido la pertinencia de las EA como constructo desde el que apreciar y propiciar las amplias y diversas oportunidades de aprendizaje que ofrece el contexto actual (Looi, 2001; Barron, 2006; Jackson, 2013; Sangrà, González-Sanmamed, & Guitert, 2013; Maina & García, 2016). Concretamente, Jackson (2013: 7) establece que las EA «comprenden los procesos y variedad de contextos e interacciones que conceden al individuo las oportunidades y los recursos para aprender, para su desarrollo y para alcanzar sus logros». | ||

| + | |||

| + | En la revisión realizada recientemente por Sangrá, Raffaghelli y Guitert-Catasús (2019) se observa el interés despertado por este concepto y los estudios que se están realizando con diversos colectivos para desvelar cómo aprovechan y, también, cómo podrían promover sus EA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Particularmente, se han desarrollado análisis en los que se exploran las EA de profesores en ejercicio y su vinculación con los procesos de aprendizaje y desarrollo profesional docente (Sangrá, Guitert, Pérez-Mateo, & Ernest, 2011; Sangrà, González-Sanmamed, & Guitert, 2013; González-Sanmamed, Santos, & Muñoz-Carril, 2016; Ranieri, Giampaolo, & Bruni, 2019; Van-den-Beemt & Diiepstraten, 2016). La confluencia de ambas líneas de reflexión e indagación resulta prometedora, sobre todo desde la asunción del desarrollo profesional como proceso de aprendizaje continuo en el que cada docente intenta mejorar su capacitación, aprovechando los recursos disponibles mediante diversos mecanismos y a través de variados contextos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | La exigencia de disponer de profesorado actualizado, con las competencias y saberes que garanticen su adecuado desempeño, y con el compromiso que requiere la tarea de formar a futuras generaciones, cobra una relevancia especial en el ámbito de la educación superior. El desarrollo profesional de los docentes universitarios constituye un factor clave para garantizar una formación superior de calidad (Darling-Hammond & Richardson, 2009; Inamorato, Gausas, Mackeviciute, Jotautyte, & Martinaitis, 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | En diversos estudios se han identificado las características, condiciones y modelos de desarrollo profesional del profesorado universitario, y se han valorado las mejoras que proporcionan (Gast, Schildkamp, & Van-der-Veen, 2017; Van Waes, De-Maeyer, Moolenaar, Van-Petegem, & Van-den-Bossche, 2018; Jaramillo-Baquerizo, Valcke, & Vanderlinde, 2019). La expansión de la tecnología está generando nuevos formatos de desarrollo profesional (Parsons & al., 2019) al facilitar el aprendizaje en cualquier momento y lugar (Trust, Krutka, & Carpenter, 2016). Concretamente, los docentes universitarios han comenzado a crear oportunidades para su propio desarrollo profesional empleando diferentes recursos como los videotutoriales o las redes sociales (Brill & Park, 2011; Seaman & Tinti-Kane, 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Estos y otros estudios ponen de manifiesto la relevancia de los recursos tecnológicos en los procesos de aprendizaje y desarrollo profesional de los docentes universitarios. La importancia de los recursos ha sido reconocida por diversos autores (Barron, 2006; Jackson, 2013; González‐Sanmamed, Muñoz‐Carril, & Santos‐Caamaño, 2019) como uno de los componentes de las EA que, junto con los contextos, las acciones y las relaciones, representa los pilares desde los que cada persona puede articular, gestionar y promover su propia EA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Como han señalado He y Li (2019), el aprendizaje se está volviendo cada vez más autodirigido e informal con el apoyo de la tecnología, de ahí la necesidad de explorar qué recursos utilizan los docentes para fomentar su desarrollo profesional desde la visión integradora que proporcionan las EA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Por una parte, asumiendo el protagonismo y el control del docente para dirigir su propio aprendizaje en función de sus necesidades, intereses y potencialidades, aspectos determinantes del desarrollo profesional (Muijs, Day, Harris, & Lindsay, 2004). Pero también, tomando en cuenta cómo los recursos inciden o pueden incidir en el desarrollo de los otros componentes de las EA (propiciando acciones, estimulando relaciones, generando contextos, etc.) que contribuirán al desarrollo de modalidades personalizadas de aprendizaje y desarrollo profesional (Yurkofsky, Blum-Smith, & Brennan, 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | La exigencia de disponer de profesorado actualizado, con las competencias y saberes que garanticen su adecuado desempeño, y con el compromiso que requiere la tarea de formar a futuras generaciones, cobra una relevancia especial en el ámbito de la educación superior. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Material y métodos== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Este estudio forma parte de un proyecto más amplio en el que se analizan las EA del profesorado universitario y su incidencia en los procesos de aprendizaje y desarrollo profesional docente. Concretamente, el propósito de esta investigación ha sido identificar las herramientas tecnológicas que configuran las EA del docente universitario y valorar en qué medida son utilizadas para propiciar su desarrollo profesional. Se han planteado las siguientes hipótesis: | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1) El género suscita diferencias significativas en la utilización de los recursos tecnológicos para el desarrollo profesional de los docentes universitarios desde la perspectiva de las EA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2) La edad genera diferencias significativas en la utilización de las herramientas tecnológicas para el desarrollo profesional de los docentes universitarios tomando como referente las EA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3) La experiencia provoca diferencias significativas en la utilización de las herramientas tecnológicas para el desarrollo profesional de los docentes universitarios desde la visión de las EA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4) La rama de conocimiento a la que pertenece el profesor origina diferencias significativas en la utilización de las herramientas tecnológicas para el desarrollo profesional de los docentes universitarios en el marco de las EA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Se ha empleado una metodología descriptiva con diseño transversal y se optó por el método de encuesta. Los datos se recogieron a través de un cuestionario diseñado ad hoc a partir de una revisión sistemática de la literatura sobre EA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Para el estudio de la validez de contenido, el instrumento inicial fue sometido a juicio de expertos. Participaron en el proceso de validación 9 profesionales con formación en la temática de estudio (EA) y en metodología de investigación educativa, todos ellos con más de 12 años de experiencia profesional universitaria. En base a sus valoraciones, se reelaboró la primera versión y, a continuación, se realizó una prueba piloto a 210 sujetos para determinar la fiabilidad del cuestionario. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tras constatar adecuados niveles psicométricos y revisar algunos aspectos gramaticales, se creó la versión definitiva en formato digital (Google Forms) y se administró vía telemática. La aplicación estuvo abierta durante 5 meses. Se contó con la colaboración de distintos responsables institucionales que distribuyeron el instrumento por correo electrónico. Se incluyó una presentación en la que se explicaba el objetivo del estudio, dentro del proyecto de investigación en el cual se enmarca, y se ofrecían las garantías de anonimato y confidencialidad. Era obligatorio responder a todas las preguntas y el tiempo promedio de respuesta fue alrededor de 12 minutos. <i id="emphasis-1"/>El cuestionario completo incluye siete escalas. Las cuatro primeras evalúan constructos ubicados en la dimensión personal de las EA y las tres siguientes indagan la dimensión experiencial de las Ecologías (González‐Sanmamed, Muñoz‐Carril, & Santos‐Caamaño, 2019). Para la realización de este estudio se utilizó una de las escalas incluidas en la dimensión experiencial, concretamente la Escala de Recursos. Para su diseño se ha tomado como base la tipología de herramientas digitales propuesta por Adell y Castañeda (2010), Castañeda y Adell (2013), Kop (2011), y Dabbagh y Kitsantas (2012).<i id="emphasis-2"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170_ov-89a951e8-6d1d-4c23-8f8f-f553083d294d-u01-01.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/5180c2e4-26d8-4da4-b9f6-0f704fac006f/image/89a951e8-6d1d-4c23-8f8f-f553083d294d-u01-01.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | La Escala de Recursos se compone de 24 ítems (Tabla 1), con respuesta tipo Likert de 1 (nada) a 5 (mucho), que se distribuyen en tres factores. En el primero de ellos, con 10 ítems, se incluyen los «recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información»; el segundo factor reúne los «recursos de creación y edición de contenido», con ocho ítems; y, finalmente, el tercer factor, conformado por seis ítems, agrupa los «recursos de interacción y comunicación». Una vez aplicado el cuestionario y atendiendo nuevamente a los criterios de la fiabilidad, se recurrió al coeficiente alfa de Cronbach, tanto a nivel global (α=.90) como para cada una de las dimensiones que componen el cuestionario: recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información (α=.82), de creación y edición de contenido (α=.75), y recursos de interacción y comunicación (α=.75). Se utilizó un muestreo no probabilístico por conveniencia. La muestra está integrada por 1.652 profesores universitarios pertenecientes a 50 universidades españolas. El 50,5% son hombres y el 49,5 % mujeres. Por edades, 23,8% tienen menos de 40 años; 33,1% están entre 41 y 50 años; y 43,2% tienen más de 51 años. El 33,4% tiene menos de 10 años de experiencia docente, el 26,3% entre 11 y 20 años, y el 40,3% más de 20 años. | ||

| + | |||

| + | La distribución por rama de conocimiento es la siguiente: el 28% pertenecen a la rama Social-Jurídica, el 21,4% a la rama de Ingeniería y Arquitectura, el 25,2% a la de Ciencias de la Salud, el 13,8% a Artes y Humanidades y, finalmente, el 11,1% a la rama de Ciencias. Los datos se analizaron con el programa IBM SPSS (versión 25). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Análisis y resultados== | ||

| + | |||

| + | En la Tabla 1, a través de los estadísticos descriptivos de cada ítem, organizados en las tres dimensiones consideradas, se pueden apreciar las herramientas con mayor y menor grado de utilización. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170_ov-28c33f6f-960c-4645-9197-9aa288b51312-u01-02.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/5180c2e4-26d8-4da4-b9f6-0f704fac006f/image/28c33f6f-960c-4645-9197-9aa288b51312-u01-02.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | En la Tabla 2 se aportan las medias, desviaciones típicas, asimetría, curtosis, así como los coeficientes de correlación de Pearson de las variables dependientes empleadas en este estudio. Se analizó la normalidad de la distribución de las variables en base al criterio adoptado por Finney y DiStefano (2006), quienes indican valores máximos de dos y siete para asimetría y curtosis, respectivamente. Se puede concluir que las variables incluidas en este estudio presentan distribuciones normales. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170_ov-9ae9d812-7503-49b8-b427-7e6ea78ecb7a-u01-03.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/5180c2e4-26d8-4da4-b9f6-0f704fac006f/image/9ae9d812-7503-49b8-b427-7e6ea78ecb7a-u01-03.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | En cuanto a las correlaciones, se observa una relación significativa y positiva entre la utilización de los recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información y de los recursos de creación y gestión de contenido (r=.70; p<.001); además, entre el empleo de recursos de creación y gestión de contenido y de recursos de interacción y comunicación (r=.64; p<.001); y, también, entre el uso de recursos de creación y gestión y de recursos de interacción y comunicación (r=.60; p<.001). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170_ov-cffc9473-b6db-4c6e-bd18-9190a7fd4ddb-u01-04.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/5180c2e4-26d8-4da4-b9f6-0f704fac006f/image/cffc9473-b6db-4c6e-bd18-9190a7fd4ddb-u01-04.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | En segundo lugar, se ha realizado un ANOVA tomando como variable independiente la edad (1=menor de 40 años; 2=entre 41 y 50 años; y 3=mayor de 50 años) y como variables dependientes el uso de los tres tipos de recursos. En el caso de los recursos de interacción y comunicación se ha recurrido a las pruebas robustas Brown-Forsythe (F*) y, posteriormente a las pruebas post-hoc Games-Howell, no asumiendo varianzas iguales. Los resultados muestran diferencias estadísticamente significativas con un tamaño del efecto pequeño en el uso de recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información [F<sub id="subscript-11">(2,1649)</sub>=20.689, p<.001; η<sub id="subscript-12">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-8">2</sup> =.02], en el uso de recursos de creación y edición de contenido [F<sub id="subscript-13">(2,1649)</sub>=12.243, p<.001; η<sub id="subscript-14">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-9">2</sup>=.01], y en el uso de recursos de interacción y comunicación [F*<sub id="subscript-15">(2,1313)</sub>=9.032 , p<.001; η<sub id="subscript-16">p</sub> <sup id="superscript-10">2</sup>=.01], en función de la edad. Concretamente, se encuentran diferencias en el uso de las tres tipologías de recursos que se han contemplado entre el profesorado que tiene menos de 40 años y el que tiene más de 51 años; y entre el que tiene entre 41 y 50 años y el de más de 51 años. Los resultados ponen de manifiesto una misma tendencia: un mayor uso de los recursos digitales para el desarrollo profesional por parte del grupo de profesorado más joven, seguido del grupo de entre 41 y 50 años, y un uso diferencialmente menor por parte del grupo de más de 51 años (Tabla 3). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gonzalez-Sanmamed_et_al_2020a-77170_ov-1dfd49ea-ff78-4dba-8f29-4738ba154c4b-u01-05.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/5180c2e4-26d8-4da4-b9f6-0f704fac006f/image/1dfd49ea-ff78-4dba-8f29-4738ba154c4b-u01-05.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | En tercer lugar, se ha realizado un ANOVA tomando como variable independiente los años de experiencia (1=menos de 10 años, 2=entre 11 y 20 años, 3=más de 21 años) y como variables dependientes el uso de los tres tipos de recursos digitales. En el caso de los recursos de interacción y comunicación se ha recurrido a las pruebas robustas Brown-Forsythe (F*) y, posteriormente a las pruebas post-hoc Games-Howell, ya que no se cumple el supuesto de homogeneidad de varianzas. Los resultados nos indican que existen diferencias estadísticamente significativas (con un tamaño del efecto pequeño) en el uso de recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión [F<sub id="s-96717e6fbd0b">(2,1649)</sub>=26.774, p<.001; η<sub id="s-abc60845277e">p</sub> <sup id="s-bd5ee351f75e">2</sup>=.03], en el uso de recursos de creación y edición de contenido [F<sub id="s-21f3452a7902">(2,1649)</sub>=15.39, p<.001; η<sub id="s-162b8c00e2b0">p</sub> <sup id="s-b81ad5588e0c">2</sup>=.02], y en el uso de recursos de interacción y comunicación [F*<sub id="s-c894475048e3">(2,1516)</sub>=15.86 , p<.001; η<sub id="s-9ec126bce9cf">p</sub> <sup id="s-166572b42cb2">2</sup>=.02], en función de los años de experiencia. Aunque el efecto es pequeño en los tres casos, se encuentran diferencias en el uso de recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información entre el profesorado que tiene menos de 10 años de experiencia y el que tiene más 21 años de experiencia; y entre el grupo de entre 11 y 20 años de experiencia y el de más de 21. Sucede algo similar con el uso de recursos de creación y edición de contenido y los recursos de interacción y comunicación, el uso es significativamente diferencial entre los tres grupos (Tabla 4). La tendencia en los tres casos es que el uso de los recursos digitales para fomentar el desarrollo profesional desciende conforme incrementa la experiencia docente. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finalmente, se llevó a cabo un último ANOVA tomando como variable independiente la rama de conocimiento (1=Social-Jurídico, 2=Ingeniería-Arquitectura, 3=Ciencias de la Salud, 4=Artes-Humanidades, 5=Ciencias), y como variable dependiente el uso de recursos de interacción y comunicación. Paralelamente, como las otras dos variables dependientes (recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información, y recursos de creación y edición de contenido) no cumplían el supuesto de homocedasticidad, se recurrió a las pruebas robustas Brown-Forsythe (F*) y, posteriormente a las pruebas post-hoc Games-Howell. Los resultados muestran diferencias estadísticamente significativas con un tamaño del efecto pequeño en el uso de recursos de recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información [F*<sub id="s-7e33b4fb1f4d">(4,1384)</sub>=4.29, p<.01; η<sub id="s-67f0cd6d2150">p</sub> <sup id="s-37e8bc3ed993">2</sup>=.01], en el uso de recursos de creación y edición de contenido [F*<sub id="s-f95f8f6a6fe9">(4,1336)</sub>=7.29, p<.001; η<sub id="s-e0692bc010b6">p</sub> <sup id="s-4bbc88243dbf">2</sup>=.017], y en el uso de recursos de interacción y comunicación [F<sub id="s-0535cfe25873">(4,1647)</sub>=19.92 , p<.001; η<sub id="s-39086e90615f">p</sub> <sup id="s-f74bad0b10ff">2</sup>=.046,], en función de los años de experiencia (Tabla 5).Aunque el tamaño del efecto es pequeño, se encuentran diferencias significativas en el uso de recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información entre el profesorado perteneciente a la rama de ciencias y el de las demás ramas, presentando este grupo los índices más bajos de utilización de este tipo de recursos. En este caso, el profesorado de la rama Social-Jurídica presenta los valores más altos de utilización. En el uso de recursos de creación y edición de contenido, se puede observar que es el grupo de Artes y Humanidades el que presenta mayores índices de utilización, seguido del profesorado de Ciencias de la Salud y de los docentes de la rama Social-Jurídico; los grupos que utilizan en menor medida estos recursos son el de Ingeniería y Arquitectura, y el de Ciencias. En cuanto a los recursos de interacción y comunicación, destaca el profesorado de la rama Social-Jurídica por presentar los índices más elevados de utilización de este tipo de herramientas, seguido del grupo de Ciencias de la Salud y del de Artes y Humanidades; siendo el profesorado de Ingeniería y Arquitectura y el de Ciencias, el que menos utiliza estos recursos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | En la Tabla 5 también se puede observar que la tendencia a la utilización de recursos de creación y edición, y de interacción y comunicación es mayor que la utilización de recursos de acceso, búsqueda y gestión de la información en todas las ramas de conocimiento. Destaca la escasa utilización de las herramientas digitales por parte del profesorado de Ciencias respecto al profesorado del resto de ramas de conocimiento. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Discusión y conclusiones== | ||

| + | |||

| + | En primer lugar, cabe señalar que este estudio se sitúa en una línea de investigación aún emergente que todavía necesita ser fortalecida conceptualmente y explorada empíricamente. Además, puede considerarse pionero, por cuanto los escasos trabajos disponibles sobre los procesos de desarrollo profesional en el marco de las EA se han realizado con docentes de niveles no universitarios. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Un análisis global de los resultados permite vislumbrar que los recursos más utilizados para el desarrollo profesional son: correo electrónico, ofimática, gestores de correo, agenda, aula virtual, almacenamiento en la nube, calendarios digitales, y videotutoriales. Son todas ellas herramientas de uso cotidiano en la labor docente y, quizás, precisamente por eso, los instrumentos más accesibles y manejables para propiciar los procesos de actualización y mejora continua. Cada docente va incluyendo unas u otras herramientas en su ecología a través de diversas experiencias, interacciones y contextos por los que transita a lo largo de su trayectoria vital, y se convertirán en recursos para el desarrollo profesional en la medida y de la forma en la que sean activados de manera consciente y autodirigida para propiciar un aprendizaje situado y personalizado. De hecho, investigaciones realizadas sobre la competencia digital (Durán, Prendes, & Gutiérrez, 2019) o estudios acerca del TPACK (Jaipal & al., 2018) en el profesorado de enseñanza superior, confirman la necesidad de potenciar la integración de la tecnología en la universidad y de reforzar la capacitación tecnológica de los profesores. Es responsabilidad de cada docente, y también de las propias instituciones, facilitar el acceso y potenciar el uso de los recursos tecnológicos que permitan configurar una ecología enriquecida desde la que cada docente podría orientar su propio desarrollo profesional. | ||

| + | |||