m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 588726920 to Pineiro-Naval Morais 2019a) |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | <span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>[[#article_en|Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)]]</span> | |

| + | |||

| + | [[Media:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830.pdf|<span style="color:#0645AD; font-weight: bold">Download the PDF version</span>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Resumen == | ||

| + | |||

| + | This paper approaches the state of academic production in communication confined to the Hispanic sphere (Spain and Latin America) during the period extending between 2013 and 2017. As in previous meta-research, the aim here is to highlight potential shortcomings in the discipline, both theoretically and methodologically. From an instrumental standpoint, a systematic, objective and quantitative content analysis was implemented on a probabilistic sample of 1,548 articles from the seven main journals in the field, all indexed in the first quartiles of the SJR-Scopus ranking. Aside from the percentage report for each variable, two-stage cluster analyses were performed twice to identify statistically significant publication patterns. As far as the results are concerned, it is worth highlighting the empirical nature of the studies, generally relying on quantitative methodologies, although no specific theoretical corpora are referenced. On the other hand, and although social networks and ICTs have gained a notable prominence, traditional media continue to be, collectively, the most prominent in communication research. Finally, the challenges of the field seem to revolve around two axes: providing studies with methodological robustness and, above all, with the theoretical background necessary to confront, with guarantees, the understanding of the liquid communicative manifestations that flow, at great speed, from the Information Society. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Resumen= | ||

| + | |||

| + | El presente trabajo aborda el estado de la producción académica en comunicación circunscrita al ámbito hispánico España e Hispanoamérica durante el período que transcurre de 2013 a 2017. Al igual que en otras metainvestigaciones precedentes, el objetivo aquí radica en poner de manifiesto las posibles carencias de la disciplina, tanto a nivel teórico como metodológico. Desde un punto de vista instrumental, se implementó un análisis de contenido sistemático, objetivo y cuantitativo sobre una muestra probabilística de 1.548 artículos pertenecientes a las siete principales revistas del área, todas ellas indexadas en los primeros cuartiles del ranking SJR-Scopus. Además del reporte porcentual de cada variable, se ejecutaron dos análisis de conglomerados bietápicos para identificar patrones de publicación estadísticamente significativos. En lo que a los resultados respecta, cabe destacar el cariz empírico de los trabajos, apoyados habitualmente en metodologías cuantitativas, aunque sin hacer alusión a corpus teóricos concretos. Por otro lado, y si bien las redes sociales y las TIC han cobrado un notable protagonismo, los medios tradicionales continúan siendo, de manera agregada, los de mayor relieve en la investigación en comunicación. Finalmente, los desafíos del área parece que girarán en torno a dos ejes: nutrir a los estudios de la robustez metodológica y, muy en especial, del acervo teórico necesarios para afrontar, con garantías, la comprensión de las líquidas manifestaciones comunicativas que manan, a gran velocidad, de la Sociedad de la Información. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Meta-research, communication, content analysis, academic papers, impact journals, Scopus, Spain, Latin America | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Metainvestigación, comunicación, análisis de contenido, artículos académicos, revistas de impacto, Scopus, España, Hispanoamérica | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introduction== | ||

| + | |||

| + | While not exhaustive, it is necessary to highlight the growing proliferation of reflections from the Hispanic sphere on communication as a field of theoretical study (De-la-Peza, 2013; Fuentes-Navarro, 2017; Moreno-Sardà, Molina, & Simelio-Solà, 2017; Piñuel, 2010; Silva & de-San-Eugenio, 2014; Vassallo & Fuentes-Navarro, 2005; Vidales, 2015). At the same time, numerous efforts have been made to understand the heterogeneous methodological approaches used to conduct research in this prolific area (Castillo & Carretón, 2010; Lozano & Gaitán, 2016; Marí-Sáez & Ceballos-Castro, 2015; Miquel-Segarra, 2018; Ortega-Mohedano, Azurmendi, & Muñoz-Saldana, 2018; Saperas, 2018). | ||

| + | |||

| + | This abundance of contributions is due to the fact that “the interest in meta-research in communication has once again gained strength” (Caffarel-Serra, 2018: 284), and has done so, in effect, backed by two essential factors: first of all, “the search for a system with which to bring order the theoretical findings in the field” (Martín-Algarra, 2008: 153); and, second, the mastery of techniques that enable the attainment of those findings. In this respect, one of the most important collective initiatives in Spain has been the recent “MapCom Project”, to which we will return later by referencing work done by some of its members. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is, however, a certain dissent around the hierarchy that these two tasks −theoretical reflection and methodological application− hold within academia. In this sense, the most critical voices call attention to “a tendency to continue encouraging a purely instrumental research model, with a certain degradation of theory as an end in itself” (Sierra, 2016: 46). With regard to empirical deployment, and although they are not mutually exclusive, the debate between quantitative and qualitative traditions is no less evocative. There are authors who highlight the rise of a phenomenological perspective, centered on “processes, language and human experience where culture and communication are inexhaustible sources of meanings” (Salinas & Gómez, 2018: 11). From another angle, “the emergence of new research techniques and new tools for the quantitative (statistical) analysis of communication not only constitutes a technical advance, but also substantially affects the development of communication as a scientific discipline and, in particular, has a decisive influence on the development of more sophisticated theories” (Igartua, 2012: 17). In light of the foregoing, the present study emerges with a clear purpose: to X-ray the current state of research in communication through the analysis of papers published in major Spanish and Latin American journals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===State of the art: Identification of previous empirical studies=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this section, a brief chronological overview of the main prior empirical references concerning both the Spanish and international contexts will be made. Beginning with our immediate environment, Caffarel-Serra, Ortega-Mohedano and Gaitán-Moya (2017) focus on the analysis of a representative sample of 288 documents relating to the period 2007-2014: 239 doctoral theses and 49 research projects, reaching the conclusion that 60.71% of the papers are confined to the study of mass media (49.45% traditional versus 11.26% digital). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Along these lines, Goyanes, Rodríguez-Gómez and Rosique-Cedillo (2018) record 3,653 articles published in the 11 leading Spanish journals from 2005 to 2015. Among its many findings, the prevalence of journalism (press and journalistic practices), audiovisual communication (film and television) and studies on audiences and receivers are noteworthy, as they all account for 51% of scientific production. Based on the data provided by some authors and others, we postulate that: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H1: traditional media will have a greater role than digital media. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In one of their latest studies, Martínez-Nicolás, Saperas and Carrasco-Campos (2019) disclose the findings of a content analysis conducted on a large sample of 1,098 articles from the leading communication journals in Spain during the 1990-2014 period, allowing them to trace different research evolution timelines. As the main result of their meticulous work, it is worth noting that almost 80% of the articles constituted empirical research, while 18% were theoretical-conceptual and only 2% methodological. Thus, we contend that: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H2: the works in the sample will exhibit a pronounced empirical approach. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the international level, Bryant and Miron's study (2004) includes a sample of 1,806 articles published in the journals “Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly”, “Journal of Communication” and “Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media” between 1956 and 2000. After their inquiry, they declare that Framing Theory is the most prominent, followed closely by Agenda Setting and Cultivation Theory. Therefore, it seems coherent to pose that: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="subscript-1">3</sub>: Framing Theory will be the most recurring theoretical corpus. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | For their part, Potter and Riddle (2007) examine 962 articles from 16 high-impact journals in the period 1993-2005, concluding that 71.4% of the studies reviewed use quantitative methods −where the survey with 32% and the experiment with 29% prevail− and 15.4% qualitative techniques. This logic prompts a new hypothesis, as well as an intimately associated research question: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-d86ad60ae1c1">4</sub>: quantitative methods will have a greater presence than qualitative methods. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | RQ1: What kind of samples will the authors of empirical papers use? | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | With regard to empirical deployment, and although they are not mutually exclusive, the debate between quantitative and qualitative traditions is no less evocative. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gómez-Rodríguez, Morrell and Gallo-Estrada (2017) focused on the journal “Comunicación y Sociedad”, a leading publication in Mexico. They evaluated a total of 209 papers assigned to the 2004-2016 cycle and identified some recurrent themes, which fall under the labels of: sociocultural environment (43.6%), academic (24.9%), socioeconomic (16.7%) and sociopolitical (14.8%). Therefore, and in relation to the papers pertaining to our study, we ask ourselves: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | RQ2: What topics will be addressed most frequently? | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, Walter, Cody and Ball-Rokeach (2018) aim to dissect 1,574 articles published in “Journal of Communication” from 1951 to 2016, performing a longitudinal analysis and comparing stages. In the most recent one, from 2010 to 2016, they found that the audience (69.3%) was the main player in the studies as opposed to the message (19.3%), the source and the policies (both with 4.6%). On the other hand, the dominant research paradigm was positivism (87.5%), well above critical and cultural −both of which were evidenced in 4.6% of studies− and rhetorical (3%). Consequently, two new hypotheses emerge: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H5: the main object of study will be the audience. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H6: the dominant paradigm to which studies adhere will be positivist. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next, the method used in the study will be described, supported by all the preceding empirical initiatives. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Material and method== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Objective and sample=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The purpose of the study was to outline the state of communication research in the Hispanic sphere through the examination of academic papers. These works, which have constituted the units of analysis, have been grouped ex post to identify, in a statistically significant way, patterns of publication or clusters, also compared, according to their impact factor and geographical origin of the journals where they were included (Spain or Latin America). | ||

| + | |||

| + | For this purpose, a content analysis was performed for being a systematic, objective and quantitative method (Riffe, Lacy, & Fico, 2014; Wimmer & Dominick, 2011), commonly applied to the study of academic texts, as we have seen in the previous section. Initially, one of the key considerations in any content analysis lies in designing a sampling plan (Igartua, 2006) which, in this case, was “multi-stage” (Neuendorf, 2016). Therefore, and in a first phase, the journals selected were those with the greatest impact in 2017 −the latest year for which data are available− in the international database “SJR-Scopus” in the category of communication (www.scimagojr.com). It was determined that journals had to rank in the first two quartiles in order to be rated as high-impact, resulting in a total of seven titles, sorted according to their position in the ranking: “Comunicar” (Q1), “El Profesional de la Información” (Q1), “Communication & Society” (Q2), “Revista Latina de Comunicación Social” (Q2), “Cuadernos.info” (Q2), “Comunicación y Sociedad” (Q2) and “Palabra Clave” (Q2). Likewise, and from 2017 onwards, it was deemed reasonable to go back five years, to 2013, in order to give the sample a certain time perspective. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In short, all those articles were stored −except editorials and reviews− contained in the websites of the seven journals during the period in question, generating a sample of n=1,548 articles. This figure represents 48.77% of the universe of published works (N=3,174) in each and every one of the Spanish and Latin American journals that were indexed in SJR-Scopus in this five-year period, which represented a margin of error of ~1.8% for a 95% confidence interval. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Categories of analysis, coding and reliability=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a guide for the examination of this representative corpus of analysis, and based on other previous studies (Barranquero & Limón, 2017; Caffarel-Serra, Ortega-Mohedano, & Gaitán-Moya, 2017; Gómez-Rodríguez, Morrell, & Gallo-Estrada, 2017; Goyanes, Rodríguez-Gómez, & Rosique-Cedillo, 2018; Martínez-Nicolás & Saperas, 2016; Martínez-Nicolás, Saperas, & Carrasco-Campos, 2019; Saperas & Carrasco-Campos, 2018; Walter, Cody, & Ball-Rokeach, 2018), a codebook was prepared consisting of the following nominal polychotomous variables, along with their reliability indicator: | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1) Type of article (<i id="emphasis-1">α<sub id="s-647d5c58555f">k</sub> </i>=0.92): 1=empirical, 2=theoretical/essayistic, or 3=methodological. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2) In the case of empirical work, what method (<i id="emphasis-2">α<sub id="subscript-2">k</sub> </i>=0.83) is used? (Table 1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3) In the case of empirical work, what type of sample (<i id="emphasis-3">α<sub id="subscript-3">k</sub> </i>=0.84) is utilized?: 0=non-empirical work, 1=probability sample, or 2=non-probability sample. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4) Theory (<i id="emphasis-4">α<sub id="subscript-4">k</sub> </i>=0.70) that provides a conceptual basis for the study (Table 1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 5) Main object of study (<i id="emphasis-5">α<sub id="subscript-5">k</sub> </i>=0.93): 1=source, 2=message, 3=audience, or 4=policies/structure. | ||

| + | |||

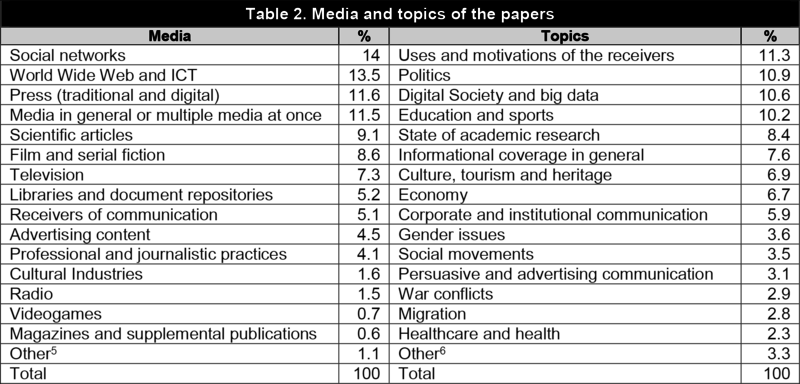

| + | 6) Main means of communication or documentary support (<i id="emphasis-6">α<sub id="subscript-6">k</sub> </i>=0.87) in the article (Table 2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 7) General topic (<i id="emphasis-7">α<sub id="subscript-7">k</sub> </i>=0.87) of the work (Table 2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 8) Paradigm (<i id="emphasis-8">α<sub id="subscript-8">k</sub> </i>=0.96) where research is framed (Walter, Cody, & Ball-Rokeach, 2018): 1=positivist: study supported by empirical assumptions and verifiable hypotheses, using quantitative or mixed methods; 2=cultural: qualitative study about the everyday practices that create and sustain culture; 3=critical: study focused on questions of power, political economy, status quo and social structure; or 4=rhetorical: study that conceives communication as the practical art of discourse. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In total, 8 multi-categorical variables in addition to those used to identify the unit of analysis; that is, the number of the article, its publication year and the journal where it appears. Likewise, the SJR impact factor of the journals during the five years examined was collected, assigning to each unit of analysis the average impact factor of the journal in the year in which it appeared. This parameter, which acted as an independent variable, was of great help in profiling the types of articles (or clusters) resulting from the processing of the results in more detail. Finally, the data collection, which ran from September 3 to December 21, 2018, involved a team of two coders. After this process, and in order to check the reliability of their work, a random subsample was selected from ~10% of the cases, which both coders analyzed. The statistical parameter used for the reliability calculation was the Krippendorff alpha (Krippendorff, 2011; 2017), found by using the “Kalpha macro” (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007) for SPSS (version 24). As can be seen above, the reliability of the eight variables was very satisfactory, while the average rose to <i id="emphasis-9">M</i> (α<sub id="subscript-9">k</sub>)=0.87 (<i id="emphasis-10">SD</i>=0.07). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Analysis and results== | ||

| + | |||

| + | This section is structured in the following way: an initial section, as a preamble, with the percentage and individualized report of codebook items; and a block where it was used −in duplicate− two-stage cluster analysis, “an exploration tool designed to uncover the natural groupings of a data set” (Rubio-Hurtado & Vilà-Baños, 2017: 118), accompanied by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and contingency tables (<i id="e-f91e72d7af4d">χ</i> <sup id="s-c2656ff78f63">2</sup>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Univariate report=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Firstly, with regard to the type of article published in the journals from the sample (H<sub id="s-a9e4c86bf882">2</sub>), there is a marked tendency towards the empirical (80.9%) as opposed to the theoretical-essayistic (12.8%) and the methodological (6.3%). Therefore, it is interesting to note both the methodological techniques used in this set of empirical works and the different theories and concepts used in the entirety of the works (Table 1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830-f50c5191-46e2-4076-8279-327b2aac8f4c-ueng-10-01.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/44cb883c-7298-4bbf-a9e3-dfce9f28b963/image/f50c5191-46e2-4076-8279-327b2aac8f4c-ueng-10-01.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | If we group the methods into quantitative, qualitative and mixed, we find that the former are present in 46.8% of the papers, the latter in 24.9% and, thirdly, triangulation is present 7.9% of the time (H4). Another important aspect at the methodological level lies in the sample design (RQ<sub id="s-de817033758c">1</sub>). In this sense, 61.4% of the papers resort to non-probability sampling compared to 19.4% who use statistical criteria for the handling of representative samples −it should be remembered that the remaining 19.1% are non-empirical studies. In relation to the theoretical framework (H<sub id="s-1e2ee30c883e">3</sub>), it is worth pointing out that the proportion of texts that rely on some specific conceptual scaffolding as opposed to those that do not is practically the same: 50.2% as opposed to 49.8%. On an individual basis, Media Literacy (8.3%) and Framing Theory (5.1%) are the most widespread. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830-84381ad6-b878-4513-ac99-6fd4a7ee725d-ueng-10-02.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/44cb883c-7298-4bbf-a9e3-dfce9f28b963/image/84381ad6-b878-4513-ac99-6fd4a7ee725d-ueng-10-02.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | With regard to the object of study −in its broadest and most generic sense− (H<sub id="s-d8cf806d742c">5</sub>), the intermediate link in the process −that is, the message− is the protagonist par excellence (44.6%) of the papers, followed by the audience (21.3%), the source (17.1%) and, lastly, the communication policies and structure (17%). The means or, alternatively, the documentary supports on which the papers focus, as well as their general topics, are distributed as follows (Table 2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | If we aggregate traditional media, we obtain 38.8% of the works compared to 28.2% of digital media (H<sub id="s-55d8c8a4acdb">1</sub>). For their part, the themes around which the studies revolve are also the most diverse (RQ<sub id="s-ec432b38dfdf">2</sub>), highlighting the uses and motivations of the receivers (11.3%). To complete the percentage review of the variables in the codebook, we find the paradigm to which the articles are ascribed (H6). In this sense, the one that dominates Spanish and Latin American research in communication is positivistic (56%), at a great distance from cultural (21.1%), critical (14.9%) and, most particularly, rhetorical (8%). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Cluster analysis=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the multivariate level, a first two-stage cluster analysis was performed which covers both continuous and categorical variables (Rundle-Thiele & al., 2015), in which we included the 6 most relevant items of the codebook; namely: the theory employed in the articles, the method, the object of the study, the communication medium in which they are centered, the topic in question and the paradigm within which the sample studies are circumscribed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830-7acd5ecb-54ae-4e8f-991a-68127e2fa820-ueng-10-03.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/44cb883c-7298-4bbf-a9e3-dfce9f28b963/image/7acd5ecb-54ae-4e8f-991a-68127e2fa820-ueng-10-03.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The silhouette measure of cohesion and separation, which alludes to cluster quality and must exceed the minimum level of 0.0 (Norušis, 2012), is 0.2, an acceptable value although regular. On the other hand, the importance of all the predictive items in the configuration of the groups is very high, since four of them reached the maximum value of 1 (topic, medium, object and method), another one was 0.96 (theory) and the definitive one was 0.78 (paradigm). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830-cf88ff1c-94f1-450d-a495-a05bc44f3fbd-ueng-10-04.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/44cb883c-7298-4bbf-a9e3-dfce9f28b963/image/cf88ff1c-94f1-450d-a495-a05bc44f3fbd-ueng-10-04.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Subsequently, the 6 clusters resulting from this first extraction presented a size coefficient of 1.54, which denotes some homogeneity between them, as can be seen in Table 3. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Starting from the creation of the 6 groups, these can be compared according to their SJR impact factor. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) shows statistically significant differences between clusters [<i id="e-08aa543ecfa8">F<sub id="s-d7a678db03f8">6 Clusters x SJR-IF</sub> </i> (5; 1,542)=18.66; <i id="e-40195062d848">p</i><0.001; <i id="e-e58be51cd528">ɳ</i> <sup id="superscript-1">2</sup>=0.057]. More specifically, and after Dunnett's T3 post-hoc test, it was deduced that the “3” and “6” clusters are those that show the greatest imbalances [<i id="e-7eb0b5d1d93e">t</i>(528)=−6.903; <i id="e-790b6d3fcd1e">p</i><0.001; <i id="e-99b96d573a0e">d</i>=−0.624], labeled as medium size according to “effect size” (Cohen, 1988; Johnson et al., 2008). Also, the 6 clusters were cross-referenced with the journals where the papers are published, recoding them into two groups: Spanish versus Latin American. The following contingency table reflects the distribution of the two according to publications. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In terms of the values shown in Table 4, significant differences are observed in 4 of the 6 clusters [<i id="e-45ed09c564e7">χ</i> <sup id="s-d0b61217aa3f">2</sup>(5, <i id="e-3528b93d521a">N</i>=1,548)=87.52; <i id="e-70699f6d6651">p</i><.001; <i id="e-6c4bb914769d">v</i>=0.238]. More specifically, and taking into account the corrected standardized residuals, Latin American journals tend to include article types 3 and 5 to a greater extent, while Spanish journals opt for cases 4 and 6. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830-78860559-e577-4aac-8148-7efbdd9162b2-ueng-10-05.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/44cb883c-7298-4bbf-a9e3-dfce9f28b963/image/78860559-e577-4aac-8148-7efbdd9162b2-ueng-10-05.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The second two-stage cluster analysis differs from the previous one in only one of the items used for its execution: the variable “theory”, which was recoded to take into account only those works that employed some kind of conceptual corpus, considering the rest as “missing”. The silhouette measure of cohesion and separation reached 0.3, an even more acceptable value. As far as the importance of the predictive items is concerned, the method becomes the most prominent element (with a value of 1), followed by the object of study (value 0.92), the theory (value 0.52), the topic (value 0.42) and, ultimately, the paradigm and the medium (both with a value of 0.40). The four clusters derived from the analysis have a size coefficient (from the largest to the smallest) of 2.20, which is not problematic (Tkaczynski, 2017). Below is a profile of the four clusters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830-6899a287-37a1-449b-8b76-2eb63efbec99-ueng-10-06.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/44cb883c-7298-4bbf-a9e3-dfce9f28b963/image/6899a287-37a1-449b-8b76-2eb63efbec99-ueng-10-06.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | These 4 clusters can also be compared according to their impact factor. Thus, this new analysis of variance reveals the existence of differences between groups according to their SJR-IF once again [<i id="e-bf05fe7a48c0">F<sub id="s-6b9c7c063a18">4 Clusters x SJR-IF</sub> </i> (3; 773)=26.79; <i id="e-6e685fde014f">p</i><0.001; <i id="e-c41cca878344">ɳ</i> <sup id="s-d3988d9cb485">2</sup>=0.094]. Comparatively, and according to Dunnett's T3 post-hoc test, it is clusters 1 and 4 that reveal the greatest imbalances [<i id="e-380ad38785ae">t</i>(388)=−7.55; <i id="e-afcc570971fd">p</i><0.001; <i id="e-8443db3b0e84">d</i>=−0.831], characterized by an elevated size according to “effect size” (Cohen, 1988; Johnson et al., 2008). Finally, these four clusters were cross-referenced with the journals where the articles are published. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the values shown in Table 6, significant differences are observed in all clusters [<i id="e-fb065fe7d68d">χ</i> <sup id="s-7ef31e83f891">2</sup>(3, <i id="e-a03709fffd84">N</i>=777)=53.33; <i id="e-0cfded949a43">p</i><0.001; <i id="e-40ff5d2d1b5f">v</i>=0.262]. On the basis of the corrected standardized residuals, Latin American journals tend to include article types 1 and 3 to a greater extent, while Spanish journals prefer cases 2 and 4. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Discussion and conclusions== | ||

| + | |||

| + | In short, the findings derived from this study enable us to assert that, although social networks and ICTs have gained much prominence, conventional media continue to be, in an aggregate manner, the most important in current communication research, which in turn reveals a markedly practical character. Somehow, a certain “lack of reflection on its epistemological dimension, on its conceptual definition” (Vidales, 2015: 12) is noted, appealing in overwhelming proportion to its empirical aspect. In this sense, the most common methodologies are quantitative, although some shortcomings are evident in their more canonical application, especially with regard to the use of representative samples (an unusual practice). From another perspective, the fact that accepted practice lies in the execution of empirical works should in no way imply the precariousness of its theoretical foundation. However, it is astonishing that almost half of the studies do not appeal to a theory or, at least, to some kind of solid conceptual notion on which to base their further research. As for the articles that do refer to some kind of theoretical corpus, Media Literacy stands out, one of the paradigms that obtains greater visibility, for example, in the journal “Comunicar” −although not exclusively−, and Framing Theory, in tune with international trends and other previous studies in the Hispanic sphere (Piñeiro-Naval & Mangana, 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Continuing with this brief summary, and despite the fact that messages are the primary object of study, one theme stands out above the others: the uses and motivations of receivers in their interaction with media artifacts. Bearing in mind that the audience is the second object of study and that the survey is also the second most used method, there is a trend towards greater concern for processes and effects. Nevertheless, until 2017, content analysis studies −or, alternatively, discourse analysis− still hold the message in a prominent place; these works are all encompassed, simultaneously, in the positivist paradigm. The following list summarizes, in abbreviated form, the answers to the hypotheses and research questions formulated: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-3342be9c0560">1</sub>. Traditional Media > Digital Media (accepted). | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-40d05a9f8cfe">2</sub>. Empirical Works > Theoretical / Methodological (accepted). | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-9e2d113bfeba">3</sub>. Most recurring corpus: Framing Theory (partially accepted). | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-41554010738d">4</sub>. Quantitative Methods > Qualitative Methods (accepted). | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-b6ee9608c3f6">5</sub>. Main object of study: Audience (rejected). | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-9e246316c0be">6</sub>. Positivist Paradigm > Cultural / Critical / Rhetorical (accepted). | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | PI<sub id="s-0db93e9ec03f">1</sub>. Types of samples in empirical studies? Non probabilistic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | PI<sub id="s-ca4a32724cf9">2</sub>. Most frequent topic? Uses and motivations of receivers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another aspect of the work that should be highlighted −perhaps the most novel− revolves around the detection of significant publication patterns, also known as clusters. In short, there are two opposite poles. On the one hand, we find a series of positivistic works focused on the audience and its interaction with ICTs and social media that, on a theoretical level, rely on a Media Literacy trend while, on an empirical level, use surveys to approach the receivers of communication. These papers, usually included in journals of Spanish origin, are the ones with the highest impact factor. On the other side of the scale emerge studies framed in the cultural paradigm that, by means of a qualitative case study, analyze the narrative structure of cinematographic messages −or, alternatively, of serial fiction. These papers have a greater presence in Latin American journals, which implicitly results in a lower impact factor. In short, it seems clear that “research in communication is an object of study that will continue to develop in our country following the trends that are consolidated in a society and a market that are increasingly more communicative” (Caffarel-Serra, Ortega, & Gaitán, 2018: 69). Meta-research will therefore fulfill a fundamental mission in the eclectic field of Communication Sciences: to highlight the shortcomings of the discipline and to warn academics of the risks it will face if not addressed. In light of the results of the study, the most demanding challenges will lie in the two tasks indicated at the beginning of the text: to provide research with a remarkable methodological robustness and, especially, with a rich theoretical repertoire so that its authors can understand and assimilate, with guarantees, the liquid communicative manifestations that flow very quickly from the Information and Knowledge Society. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other topics include: environment, history, religion, humanism, philosophy, aesthetics, poetry or legislation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other media include: photographs, infographs, drawings, graffiti or videos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other methods that appear sporadically include: situational analysis, data envelopment analysis or iconographic analysis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other theories and concepts specifically identified are: Cultivation Theory, Stakeholders Theory, Priming, Spiral of Silence, Conceptual Metaphor Theory, Grounded Theory, Transparency, Neuromarketing, Gamification, Augmented Reality, e-WoM, Internet of Things, Memes or Think Tanks. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note that “Comunicar” is also indexed in Education and Cultural Studies, while “El Profesional de la Información” and “Cuadernos.info” appear in Information Sciences, assumed as areas related to Communication. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Information about the MapCom project: www.mapcom.es | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ol><li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other topics include: environment, history, religion, humanism, philosophy, aesthetics, poetry or legislation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other media include: photographs, infographs, drawings, graffiti or videos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other methods that appear sporadically include: situational analysis, data envelopment analysis or iconographic analysis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other theories and concepts specifically identified are: Cultivation Theory, Stakeholders Theory, Priming, Spiral of Silence, Conceptual Metaphor Theory, Grounded Theory, Transparency, Neuromarketing, Gamification, Augmented Reality, e-WoM, Internet of Things, Memes or Think Tanks. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note that “Comunicar” is also indexed in Education and Cultural Studies, while “El Profesional de la Información” and “Cuadernos.info” appear in Information Sciences, assumed as areas related to Communication. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Information about the MapCom project: www.mapcom.es | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ol><li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | BarranqueroA., LimónN., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Objetos y métodos dominantes en comunicación para el desarrollo y el cambio social en las Tesis y Proyectos de Investigación en España (2007-2013)&author=Barranquero&publication_year= Objetos y métodos dominantes en comunicación para el desarrollo y el cambio social en las Tesis y Proyectos de Investigación en España (2007-2013)]Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 72:1-25 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | BryantJ., MironD., . 2004.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Theory and research in mass communication&author=Bryant&publication_year= Theory and research in mass communication].Journal of Communication 54(4):662-704 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Caffarel-SerraC., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La metainvestigación en comunicación, una necesidad y una oportunidad&author=Caffarel-Serra&publication_year= La metainvestigación en comunicación, una necesidad y una oportunidad].adComunica 15:293-295 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | C.Caffarel-Serra,, F.Ortega-Mohedano,, J.A.Gaitán-Moya,, . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Investigación en Comunicación en la universidad española en el periodo 2007-2014&author=C.&publication_year= Investigación en Comunicación en la universidad española en el periodo 2007-2014].El Profesional de la Información 26(2):218-227 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Caffarel-SerraC., OrtegaF., GaitánJ.A., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Communication research in Spain: Weaknesses, threats, strengths and opportunities. [La investigación en comunicación en España: Debilidades, amenazas, fortalezas y oportunidades]&author=Caffarel-Serra&publication_year= Communication research in Spain: Weaknesses, threats, strengths and opportunities. [La investigación en comunicación en España: Debilidades, amenazas, fortalezas y oportunidades]]Comunicar 26(56):61-70 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CastilloA., CarretónM., . 2010.[https://bit.ly/2LZRkLd Investigación en Comunicación. Estudio bibliométrico de las Revistas de Comunicación en España].Comunicación y Sociedad 23(2):289-327 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CohenJ., . 1988.[https://doi.org/10.1016/c2013-0-10517-x Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences]. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CarmDe-la-Peza, Mar, . 2013.[https://bit.ly/30BgRh1 Los estudios de comunicación: disciplina o indisciplina].Comunicación y Sociedad 20:11-32 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fuentes-NavarroR., . 2017.[https://bit.ly/2KUafoA Centralidad y marginalidad de la Comunicación y su estudio]. Salamanca: Comunicación Social. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gómez-RodríguezG., MorrellA.E., Gallo-EstradaC., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=A 30 años de Comunicación y Sociedad: Cambios y permanencias en el campo académico de la comunicación&author=Gómez-Rodríguez&publication_year= A 30 años de Comunicación y Sociedad: Cambios y permanencias en el campo académico de la comunicación].Comunicación y Sociedad 30:17-44 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | GoyanesM., Rodríguez-GómezE.F., Rosique-CedilloG., . 2018.[https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.nov.11 Investigación en comunicación en revistas científicas en España (2005-2015): De disquisiciones teóricas a investigación basada en evidencias].El Profesional de la Información 27(6):1281-1291 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | HayesA.F., KrippendorffK., . 2007.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data&author=Hayes&publication_year= Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data].Communication Methods and Measures 1(1):77-89 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | IgartuaJ.J., . 2006.[https://bit.ly/2MQWiKU Métodos cuantitativos de investigación en comunicación]. Barcelona: Bosch. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | IgartuaJ.J., . 2012.[https://bit.ly/2EmFDZ1 Tendencias actuales en los estudios cuantitativos en comunicación].Comunicación y Sociedad 17:15-40 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | JohnsonB.T., Scott-SheldonL.A.J., SnyderL.B., NoarS.M., Huedo-MedinaT.B., . 2008.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Contemporary approaches to meta-analysis in communication research&author=Johnson&publication_year= Contemporary approaches to meta-analysis in communication research]. In: HayesA.F., SlaterM.D., SnyderL.B., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The SAGE Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research&author=Hayes&publication_year= The SAGE Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research]. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. 311-347 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | KrippendorffK., . 2011.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Agreement and information in the reliability of coding&author=Krippendorff&publication_year= Agreement and information in the reliability of coding].Communication Methods and Measures 5(2):93-112 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | KrippendorffK., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Reliability&author=Krippendorff&publication_year= Reliability]. In: MatthesJ., DavisC.S., PotterR.F., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods&author=Matthes&publication_year= The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods]. New Jersey, USA: John Wiley & Sons. 1-28 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | C.Lozano,, J.Gaitán,, . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Vicisitudes de la investigación en comunicación en España en el sexenio 2009-2015&author=C.&publication_year= Vicisitudes de la investigación en comunicación en España en el sexenio 2009-2015].Disertaciones 9(2):139-162 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Marí-SáezV.M., Ceballos-CastroG., . 2015.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Análisis bibliométrico sobre ‘Comunicación, Desarrollo y Cambio Social’ en las diez primeras revistas de Comunicación de España&author=Marí-Sáez&publication_year= Análisis bibliométrico sobre ‘Comunicación, Desarrollo y Cambio Social’ en las diez primeras revistas de Comunicación de España].Cuadernos.info 37:201-212 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Martín-AlgarraM., . 2009.[https://bit.ly/2wapqS7 La comunicación como objeto de estudio de la teoría de la comunicación].Anàlisi 38:151-172 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Martínez-NicolásM., SaperasE., . 2016.[https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2016-1150es Objetos de estudio y orientación metodológica de la reciente investigación sobre comunicación en España (2008-2014). Análisis de los trabajos publicados en revistas científicas españolas].Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 71:1365-1384 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Martínez-NicolásM., SaperasE., Carrasco-CamposA., . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La investigación sobre comunicación en España en los últimos 25 años&author=Martínez-Nicolás&publication_year= La investigación sobre comunicación en España en los últimos 25 años].Empiria 42:37-69 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Miquel-SegarraS., . 2018.[https://bit.ly/2uNJTLs Análisis de la investigación publicada en las revistas de comunicación con índice ESCI (Emerging Source Citation Index)] In: Caffarel-SerraC., GaitánJ.A., LozanoC., PiñuelJ.L., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Tendencias metodológicas en la investigación académica sobre Comunicación &author=Caffarel-Serra&publication_year= Tendencias metodológicas en la investigación académica sobre Comunicación ]. Salamanca: Comunicación Social. 109-129 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Moreno-SardàA., MolinaP., Simelio-SolàN., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=CiudadaniaPlural.com: De las humanidades digitales al humanismo plural&author=Moreno-Sardà&publication_year= CiudadaniaPlural.com: De las humanidades digitales al humanismo plural].Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 72:87-113 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | NeuendorfK.A., . 2016.[https://bit.ly/2RiyXAk The content analysis guidebook]. Oaks, California: Sage. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | NorušisM.J., . 2012.[https://bit.ly/2RgijBo IBM SPSS statistics]. River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ortega-MohedanoF., AzurmendiA., Muñoz-SaldanaM., . 2018.[https://bit.ly/2uNJTLs Metodologías avanzadas de investigación en Comunicación y Ciencias Sociales: La revolución de los instrumentos y los métodos, Qualtrics, Big Data, Web Data et al]. In: Caffarel-Serraundefined In C., GaitánJ.A., LozanoC., PiñuelJ.L., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Tendencias metodológicas en la investigación académica sobre Comunicación&author=Caffarel-Serra&publication_year= Tendencias metodológicas en la investigación académica sobre Comunicación]. Salamanca: Comunicación Social. 169-188 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ValPiñeiro-Naval,, RosMangana,, . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La presencia del framing en los artículos publicados en revistas hispanoamericanas de Comunicación indexadas en Scopus&author=Val&publication_year= La presencia del framing en los artículos publicados en revistas hispanoamericanas de Comunicación indexadas en Scopus].Palabra Clave 22(1):117-142 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | PiñuelJ.L., . 2010.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La comunicación como objeto científico de estudio, campo de análisis y disciplina científica&author=Piñuel&publication_year= La comunicación como objeto científico de estudio, campo de análisis y disciplina científica].Contratexto 18:67-107 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | PotterW.J., RiddleK., . 2007.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=A content analysis of the media effects literature&author=Potter&publication_year= A content analysis of the media effects literature].Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 84(1):90-104 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | RiffeD., LacyS., FicoF., . 2014.[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203551691 Analyzing media messages. Using quantitative content analysis in research]. New York: Routledge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rubio-HurtadoM.J., Vilà-BañosR., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=El análisis de conglomerados bietápico o en dos fases con SPSS&author=Rubio-Hurtado&publication_year= El análisis de conglomerados bietápico o en dos fases con SPSS].REIRE 10(1):118-126 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rundle-ThieleS., KubackiK., TkaczynskiA., ParkinsonJ., . 2015.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Using two-step cluster analysis to identify homogeneous physical activity groups&author=Rundle-Thiele&publication_year= Using two-step cluster analysis to identify homogeneous physical activity groups].Marketing Intelligence & Planning 33(4):522-537 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SalinasJ., GómezJ.S., . 2018.[https://bit.ly/30y5p5M Investigación cualitativa y comunicación en la era digital: una revisión crítica de la literatura científica]. In: SalinasJ., GómezJ.S., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La Investigación Cualitativa en la Comunicación y Sociedad Digital: nuevos retos y oportunidades&author=Salinas&publication_year= La Investigación Cualitativa en la Comunicación y Sociedad Digital: nuevos retos y oportunidades]. Sevilla: Egregius. 11-23 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SaperasE., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La investigación comunicativa en España en tiempos de globalización. La influencia del contexto académico y de investigación internacionales en la evolución de los estudios sobre medios en España&author=Saperas&publication_year= La investigación comunicativa en España en tiempos de globalización. La influencia del contexto académico y de investigación internacionales en la evolución de los estudios sobre medios en España]. In: Rodríguez-SerranoA., Gil-SoldevillaS., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Investigar en la Era Neoliberal. Visiones críticas sobre la investigación en comunicación en España&author=Rodríguez-Serrano&publication_year= Investigar en la Era Neoliberal. Visiones críticas sobre la investigación en comunicación en España]. Valencia: Aldea Global. 207-225 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SaperasE., Carrasco-CamposA., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Journalism research: A dominant field of communication research in Spain. A meta-research on Spanish peer-reviewed journals (2000-2014)&author=Saperas&publication_year= Journalism research: A dominant field of communication research in Spain. A meta-research on Spanish peer-reviewed journals (2000-2014)]Estudos em Comunicação 26(1):281-300 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SierraL.I., . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La paradójica centralidad de las teorías de la comunicación: Debates y prospectivas&author=Sierra&publication_year= La paradójica centralidad de las teorías de la comunicación: Debates y prospectivas].Palabra Clave 19(1):15-56 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SilvaV., de-San-EugenioJ., . 2014.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La investigación en Comunicación ante una encrucijada: De la teoría de los campos a la diseminación y diversidad gnoseológica. Estudio inicial comparado entre España, Brasil y Chile&author=Silva&publication_year= La investigación en Comunicación ante una encrucijada: De la teoría de los campos a la diseminación y diversidad gnoseológica. Estudio inicial comparado entre España, Brasil y Chile].Palabra Clave 17(3):803-827 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | TkaczynskiA., . 2017.[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1835-0_8 Segmentation using two-Step cluster analysis]. In: DietrichT., Rundle-ThieleS., KubackiK., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Segmentation in Social Marketing&author=Dietrich&publication_year= Segmentation in Social Marketing]. Singapore: Springer. 109-125 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | M.I.Vassallo,, R.Fuentes-Navarro,, . 2005. , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Comunicación: Campo y objeto de estudio. Perspectivas reflexivas latinoamericanas&author=&publication_year= Comunicación: Campo y objeto de estudio. Perspectivas reflexivas latinoamericanas]. Tlaquepaque, Jalisco: ITESO. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | VidalesC., . 2015.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Historia, teoría e investigación de la comunicación&author=Vidales&publication_year= Historia, teoría e investigación de la comunicación].Comunicación y Sociedad 23:11-43 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | WalterN., CodyM.J., Ball-RokeachS.J., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The ebb and flow of communication research: Seven decades of publication&author=Walter&publication_year= The ebb and flow of communication research: Seven decades of publication].Trends and Research Priorities. Journal of Communication 68(2):424-440 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | WimmerR.D., DominickJ.R., . 2011. , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Mass media research: An introduction&author=&publication_year= Mass media research: An introduction]. Boston: Wadsworth. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_en"></span>[[#article_es|Click to see the English version (EN)]]</span> | <span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_en"></span>[[#article_es|Click to see the English version (EN)]]</span> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | [[Media:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830_ov.pdf|<span style="color:#0645AD; font-weight: bold">Descarga aquí la versión PDF</span>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Resumen == | ||

| + | |||

| + | El presente trabajo aborda el estado de la producción académica en comunicación circunscrita al ámbito hispánico (España e Hispanoamérica) durante el período que transcurre de 2013 a 2017. Al igual que en otras metainvestigaciones precedentes, el objetivo aquí radica en poner de manifiesto las posibles carencias de la disciplina, tanto a nivel teórico como metodológico. Desde un punto de vista instrumental, se implementó un análisis de contenido sistemático, objetivo y cuantitativo sobre una muestra probabilística de 1.548 artículos pertenecientes a las siete principales revistas del área, todas ellas indexadas en los primeros cuartiles del ranking SJR-Scopus. Además del reporte porcentual de cada variable, se ejecutaron dos análisis de conglomerados bietápicos para identificar patrones de publicación estadísticamente significativos. En lo que a los resultados respecta, cabe destacar el cariz empírico de los trabajos, apoyados habitualmente en metodologías cuantitativas, aunque sin hacer alusión a corpus teóricos concretos. Por otro lado, y si bien las redes sociales y las TIC han cobrado un notable protagonismo, los medios tradicionales continúan siendo, de manera agregada, los de mayor relieve en la investigación en comunicación. Finalmente, los desafíos del área parece que girarán en torno a dos ejes: nutrir a los estudios de la robustez metodológica y, muy en especial, del acervo teórico necesarios para afrontar, con garantías, la comprensión de las líquidas manifestaciones comunicativas que manan, a gran velocidad, de la Sociedad de la Información. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =ABSTRACT= | ||

| + | |||

| + | This paper approaches the state of academic production in communication confined to the Hispanic sphere, namely, Spain and Latin America, during the period extending between 2013 and 2017. As in previous meta-research, the aim here is to highlight potential shortcomings in the discipline, both theoretically and methodologically. From an instrumental standpoint, a systematic, objective and quantitative content analysis was implemented on a probabilistic sample of 1,548 articles from the seven main journals in the field, all indexed in the first quartiles of the SJR-Scopus ranking. Aside from the percentage report for each variable, two-stage cluster analyses were performed twice to identify statistically significant publication patterns. As far as the results are concerned, it is worth highlighting the empirical nature of the studies, generally relying on quantitative methodologies, although no specific theoretical corpora are referenced. On the other hand, and although social networks and ICTs have gained a notable prominence, traditional media continue to be, collectively, the most prominent in communication research. Finally, the challenges of the field seem to revolve around two axes: providing studies with methodological robustness and, above all, with the theoretical background necessary to confront, with guarantees, the understanding of the liquid communicative manifestations that flow, at great speed, from the Information Society. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Metainvestigación, comunicación, análisis de contenido, artículos académicos, revistas de impacto, Scopus, España, Hispanoamérica | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Meta-research, communication, content analysis, academic papers, impact journals, Scopus, Spain, Latin America | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introducción== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sin ánimo de ser exhaustivos, resulta necesario subrayar la creciente proliferación de reflexiones provenientes del ámbito hispánico acerca de la comunicación como campo de estudio teórico (De-la-Peza, 2013; Fuentes-Navarro, 2017; Moreno-Sardà, Molina, & Simelio-Solà, 2017; Piñuel, 2010; Silva & de-San-Eugenio, 2014; Vassallo & Fuentes-Navarro, 2005; Vidales, 2015). De forma paralela, también son numerosos los esfuerzos centrados en comprender los heterogéneos abordajes metodológicos empleados para investigar en esta fértil área (Castillo & Carretón, 2010; Lozano & Gaitán, 2016; Marí-Sáez & Ceballos-Castro, 2015; Miquel-Segarra, 2018; Ortega-Mohedano, Azurmendi, & Muñoz-Saldana, 2018; Saperas, 2018). Esta abundancia de aportaciones se debe a que «el interés por la metainvestigación en comunicación ha vuelto a cobrar fuerza» (Caffarel-Serra, 2018: 284), y lo ha hecho, en efecto, auspiciada por dos factores esenciales: en primer lugar, «la búsqueda de una sistemática con la que ordenar los hallazgos teóricos en el campo» (Martín-Algarra, 2008: 153); y, en segundo lugar, el dominio de las técnicas que facilitan la consecución de esos hallazgos. A este respecto, una de las iniciativas colectivas de mayor calado en España ha sido el reciente «Proyecto MapCom» , al que volveremos más adelante mediante la referencia a trabajos realizados por algunos de sus miembros. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Se produce, no obstante, cierto disenso en torno a la jerarquía que estos dos quehaceres −reflexión teórica y aplicación metodológica− ostentan en el seno de la academia. En este sentido, las voces más críticas alertan sobre «una tendencia a seguir incentivando un modelo de investigación puramente instrumental, con una cierta degradación de la teoría como fin en sí mismo» (Sierra, 2016: 46). En lo tocante al despliegue empírico, y pese a no ser excluyentes entre sí, el debate que se establece entre las tradiciones cuantitativa y cualitativa no es menos sugerente. Existen autores que destacan el auge de una perspectiva fenomenológica, centrada en «los procesos, el lenguaje y la experiencia humana donde la cultura y la comunicación son fuentes inagotables de significados» (Salinas & Gómez, 2018: 11). Desde otro ángulo, «la emergencia de nuevas técnicas de investigación y de nuevas herramientas para el análisis cuantitativo (estadístico) de la comunicación, no solo constituye un avance técnico, sino que afecta sustancialmente al desarrollo de la comunicación como disciplina científica y, en particular, influye de manera decisiva en la elaboración de teorías más sofisticadas» (Igartua, 2012: 17). | ||

| + | |||

| + | A tenor de lo expuesto, el estudio que nos ocupa surge con un propósito claro: radiografiar el estado actual de la investigación en comunicación mediante el análisis de los artículos publicados en las principales revistas españolas e hispanoamericanas. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Estado de la cuestión: identificación de estudios empíricos previos=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | En este aparado se efectuará un breve recorrido cronológico por los principales referentes empíricos previos, tocantes tanto al contexto español como internacional. Comenzando por nuestro entorno inmediato, Caffarel-Serra, Ortega-Mohedano y Gaitán-Moya (2017) se centran en el análisis de una muestra representativa de 288 documentos relativos al período 2007-2014: 239 tesis doctorales y 49 proyectos de investigación, llegando a la conclusión de que el 60,71% de los trabajos se ciñen al estudio de medios de comunicación de masas (49,45% tradicionales frente a 11,26% digitales). En esta línea, Goyanes, Rodríguez-Gómez y Rosique-Cedillo (2018) toman el censo de 3.653 artículos publicados en las 11 principales revistas españolas desde 2005 hasta 2015. Entre sus múltiples hallazgos, cabe destacar el predominio del periodismo (prensa y prácticas periodísticas), la comunicación audiovisual (cine y televisión) y los estudios sobre audiencias y receptores, ya que todos ellos copan el 51% de la producción científica. Apoyados en los datos de unos autores y otros, postulamos que: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="subscript-1">1</sub>: los medios tradicionales acapararán un mayor protagonismo que los digitales. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | En uno de sus últimos trabajos, Martínez-Nicolás, Saperas y Carrasco-Campos (2019) divulgan los hallazgos de un análisis de contenido practicado sobre una amplia muestra de conveniencia de 1.098 artículos, procedentes de las revistas de comunicación referentes en España durante el lapso 1990-2014; lo cual les permite trazar distintas líneas temporales con la evolución de la investigación. Como principal extracto de su minuciosa labor, destacamos que casi el 80% de los artículos son investigaciones empíricas, mientras que el 18% son de carácter teórico-conceptual y únicamente un 2% de tipo metodológico. Así pues, sostenemos que: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H2: los trabajos de la muestra presentarán una marcada vocación empírica. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ya en el ámbito internacional, el estudio de Bryant y Miron (2004) abarca una muestra de 1.806 artículos publicados en las revistas «Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly», «Journal of Communication» y «Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media» entre 1956 y 2000. Tras su indagación, declaran que la Teoría del Framing es la más destacada, seguida a corta distancia por la Agenda Setting y la Teoría del Cultivo. Por tanto, resulta coherente plantear que: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-3d60fb52c2cc">3</sub>: la Teoría del Framing será el corpus teórico más recurrente. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Por su parte, Potter y Riddle (2007) examinan 962 artículos concernientes a 16 revistas de alto índice de impacto en el período 1993-2005, infiriendo que el 71,4% de los estudios revisados emplean métodos cuantitativos −donde prevalecen la encuesta, con un 32%, y el experimento, con un 29%−, y un 15,4% técnicas cualitativas. Esta lógica nos impulsa a postular una nueva hipótesis, así como a formular una pregunta de investigación íntimamente asociada: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H4: los métodos cuantitativos tendrán una mayor presencia que los cualitativos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | PI<sub id="s-3ab0f91bd724">1</sub>: ¿con qué tipo de muestras trabajarán los autores de los artículos empíricos? | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | En lo tocante al despliegue empírico, y pese a no ser excluyentes entre sí, el debate que se establece entre las tradiciones cuantitativa y cualitativa no es menos sugerente. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gómez-Rodríguez, Morrell y Gallo-Estrada (2017) focalizan su atención en la revista «Comunicación y Sociedad», publicación de cabecera en México. Evalúan un total de 209 artículos adscritos al ciclo 2004-2016 y detectan algunas temáticas recurrentes, que engloban bajo las etiquetas de: entorno sociocultural (43,6%), académico (24,9%), socioeconómico (16,7%) y sociopolítico (14,8%). Por ello, y en lo referente a los trabajos pertenecientes a nuestro estudio, nos preguntamos: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | PI<sub id="s-d717615f2553">2</sub>: ¿qué temáticas serán tratadas con mayor frecuencia? | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | En último lugar, el propósito de Walter, Cody y Ball-Rokeach (2018) consiste en diseccionar 1.574 artículos publicados en «Journal of Communication» desde 1951 hasta 2016, lo que también les permite efectuar un análisis longitudinal y comparar etapas. En la más reciente, desde 2010 a 2016, descubren que la audiencia (69,3%) es la gran protagonista de los estudios frente al mensaje (19,3%), la fuente y las políticas (ambas con 4,6%). Por otra parte, el paradigma dominante de las investigaciones es el positivista (87,5%), muy por encima del crítico y el cultural −ambos patentes en el 4,6% de los estudios− y del retórico (3%). En consecuencia, dos nuevas hipótesis emergen: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ul class="list" data-jats-list-type="bullet"> <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-7962bd15dd9c">5</sub>: el objeto de estudio principal será la audiencia. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | H<sub id="s-521efce24c38">6</sub>: el paradigma dominante al cual se adscribirán los artículos será el positivista. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | De inmediato se describe el método empleado en la investigación, deudor de todas estas iniciativas empíricas que la anteceden. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Material y método== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Objetivo y muestra=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | El propósito del estudio consistió en perfilar el estado de la investigación en comunicación en el ámbito hispánico a través del examen de artículos académicos. Estos trabajos, que han constituido las unidades de análisis, han sido agrupados a posteriori para identificar, de forma estadísticamente significativa, patrones de publicación o conglomerados, comparados, asimismo, en función del índice de impacto y la procedencia geográfica de las revistas donde fueron incluidos (España o Hispanoamérica). Para ello, se recurrió al análisis de contenido por ser un método sistemático, objetivo y cuantitativo (Riffe, Lacy, & Fico, 2014; Wimmer & Dominick, 2011), comúnmente aplicado al estudio de textos académicos, tal como comprobamos en el apartado anterior. De inicio, una de las consideraciones clave en cualquier análisis de contenido radica en diseñar un plan de muestreo (Igartua, 2006) que, en este caso, fue «polietápico» (Neuendorf, 2016). Por ende, y en una primera fase, fueron seleccionadas las revistas de mayor impacto en 2017 −año al que pertenecen los últimos datos disponibles− presentes en la base internacional «SJR-Scopus» en la categoría de comunicación (www.scimagojr.com). Se determinó que las revistas debían figurar en los dos primeros cuartiles para ser calificadas de impacto, resultando un total de siete cabeceras −ordenadas según su posición en el ranking−: «Comunicar» (Q1), «El Profesional de la Información» (Q1), «Communication & Society» (Q2), «Revista Latina de Comunicación Social» (Q2), «Cuadernos.info» (Q2), «Comunicación y Sociedad» (Q2) y «Palabra Clave» (Q2). Asimismo, y a partir de 2017, se estimó razonable retroceder un lustro, hasta 2013, para dotar a la muestra de cierta perspectiva temporal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | En suma, se almacenaron todos aquellos artículos −exceptuando editoriales y reseñas− contenidos en las sedes electrónicas de las siete revistas durante el período acotado, originando una muestra de <i id="emphasis-2">n=</i>1.548 artículos. Esta cifra representa el 48,77% del universo de trabajos publicados (<i id="emphasis-3">N=</i>3.174) en todas y cada una de las revistas españolas e hispanoamericanas que estaban indexadas en SJR-Scopus en este quinquenio, lo que supuso un margen de error del ~1,8% para un intervalo de confianza del 95%. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Categorías de análisis, codificación y fiabilidad=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Como guía para el examen de este corpus representativo de análisis, y fundamentado en otros estudios previos (Barranquero & Limón, 2017; Caffarel-Serra, Ortega-Mohedano, & Gaitán-Moya, 2017; Gómez-Rodríguez, Morrell, & Gallo-Estrada, 2017; Goyanes, Rodríguez-Gómez, & Rosique-Cedillo, 2018; Martínez-Nicolás & Saperas, 2016; Martínez-Nicolás, Saperas, & Carrasco-Campos, 2019; Saperas & Carrasco-Campos, 2018; Walter, Cody, & Ball-Rokeach, 2018), fue redactado un libro de códigos compuesto por las siguientes variables nominales politómicas, acompañadas de su indicador de fiabilidad: | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1) Tipo de artículo (<i id="e-3c71a9eb48e2">α<sub id="s-3ac429b1edbd">k</sub> </i>=0,92): 1=empírico, 2=teórico / ensayístico, o 3=metodológico. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2) En caso de ser un trabajo empírico, ¿qué método (<i id="e-7d8a2c5cbbfd">α<sub id="subscript-2">k</sub> </i>=0,83) se utiliza? (Tabla 1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3) En caso de ser un trabajo empírico, ¿con qué tipo de muestra (<i id="e-46084000722f">α<sub id="subscript-3">k</sub> </i>=0,84) se trabaja?: 0=no es un trabajo empírico, 1=muestra probabilística, o 2=muestra no probabilística. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4) Teoría (<i id="emphasis-4">α<sub id="subscript-4">k</sub> </i>=0,70) que le otorga un sustento conceptual al estudio (Tabla 1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 5) Objeto de estudio principal (<i id="emphasis-5">α<sub id="subscript-5">k</sub> </i>=0,93): 1=fuente, 2=mensaje, 3=audiencia, o 4=políticas / estructura. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 6) Medio de comunicación o soporte documental (<i id="emphasis-6">α<sub id="subscript-6">k</sub> </i>=0,87) protagonista del artículo (Tabla 2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 7) Temática general (<i id="emphasis-7">α<sub id="subscript-7">k</sub> </i>=0,87) del trabajo (Tabla 2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 8) Paradigma (<i id="emphasis-8">α<sub id="subscript-8">k</sub> </i>=0,96) donde se encuadra la investigación (Walter, Cody, & Ball-Rokeach, 2018): 1=positivista: estudio apoyado en suposiciones empíricas e hipótesis comprobables, que utiliza métodos cuantitativos o mixtos; 2=cultural: estudio cualitativo acerca de las prácticas cotidianas que crean y sostienen la cultura; 3=crítico: estudio centrado en cuestiones de poder, economía política, statu quo y estructura social; o 4=retórico: estudio que concibe la comunicación como el arte práctico del discurso. | ||

| + | |||

| + | En total, ocho variables multicategóricas a las que hay que sumar aquellas que sirvieron para identificar la unidad de análisis; esto es, el número del artículo, su año de publicación y la revista donde aparece. Del mismo modo, fue recogido el valor correspondiente al factor de impacto SJR de las revistas durante los cinco años examinados, asignándole a cada unidad de análisis el índice de impacto medio de la revista en el año en que apareció. Este parámetro, que ejerció como variable independiente, sirvió de gran ayuda para perfilar con más detalle los tipos de artículos (o conglomerados) fruto del procesamiento de los resultados. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finalmente, en la recogida de los datos, que transcurrió desde el 3 de septiembre hasta el 21 de diciembre de 2018, se vio implicado un equipo de dos codificadores. Tras este proceso, y para el chequeo de la fiabilidad de su labor, fue seleccionada una submuestra aleatoria del 10% de los casos, que ambos codificadores analizaron. El parámetro estadístico utilizado para el cálculo de la fiabilidad fue el alfa de Krippendorff (Krippendorff, 2011; 2017), hallado mediante el empleo de la «macro Kalpha»<i id="emphasis-9"> </i> (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007) para SPSS (versión 24). Como se puede observar líneas arriba, la fiabilidad de las ocho variables fue muy satisfactoria, mientras que el promedio ascendió a: <i id="emphasis-10">M </i> (<i id="emphasis-11">α<sub id="subscript-9">k</sub> </i>)=0,87 (<i id="emphasis-12">DT</i>=0,07). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Análisis y resultados== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Este apartado se estructura del siguiente modo: un epígrafe inicial, a modo de preámbulo, con el reporte porcentual e individualizado de los ítems del libro de códigos; y un bloque donde es empleado −por duplicado− el análisis de conglomerados bietápico, «una herramienta de exploración diseñada para descubrir las agrupaciones naturales de un conjunto de datos» (Rubio-Hurtado & Vilà-Baños, 2017: 118), acompañados de sendos análisis de la varianza (ANOVA) y tablas de contingencia (<i id="e-8b0d573b2512">χ</i> <sup id="s-addd108191cb">2</sup>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Reporte univariable=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | En primer lugar, en cuanto al tipo de artículo publicado en las revistas de la muestra (H<sub id="s-f6afb415b8ce">2</sub>), se observa una marcada tendencia hacia lo empírico (80,9%) frente a lo teórico-ensayístico (12,8%) y lo metodológico (6,3%). Por ende, es interesante reparar tanto en las técnicas metodológicas empleadas en ese conjunto de trabajos empíricos, como en las distintas teorías y conceptos manejados en la totalidad de los trabajos (ver Tabla 1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Pineiro-Naval_Morais_2019a-75830_ov-33181679-c409-4209-a0b8-6bb07c7c0ddd-u10-01.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/0e409654-d0b5-4ce6-9ea3-6fe5d599dbad/image/33181679-c409-4209-a0b8-6bb07c7c0ddd-u10-01.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||