m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 388869326 to Garcia-Perales Almeida 2019a) |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | D:/ | + | <span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>[[#article_en|Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)]]</span> |

| + | ==== Abstract ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | This article notes the low rate of highly talented or gifted students formally identified in Spain compared to international benchmarks. These students are not properly identified, so a lack of specific educational responses for these highly talented students is also expected. Trying to counteract this trend, this article presents an enrichment program imparted to a group of students with high intellectual abilities during the academic year 2017/18 over three weekly sessions during school hours, where emerging technologies were an important key in how it was delivered. The experimental design included an experimental group of high ability students and two control groups, one consisting of students with high abilities who did not receive specific educational responses and another consisting of a group of regular schoolchildren in terms of abilities. The results showed that the implementation of specific educational responses improved children’s levels of adaptation and in some cases, their school performance. These data are discussed in an attempt to recommend enrichment programs integrated into the classroom as an appropriate educational response to gifted or high ability students. Attention to diversity of all students in the classroom is possible, for example by resorting to ICT, increasing the educational inclusion of students with high intellectual capacity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Media:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244.pdf|<span style="color:#0645AD; font-weight: bold">Download the PDF version</span>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 1. Introduction ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Organic Law 8/2013, of the 9th of December, for the improvement of educational quality (LOMCE) in Spain includes the following types of students within the term Students With Specific Educational Support Needs (ACNEAE): Students with Special Educational Needs (ACNEE, including students with auditory, motor, intellectual or visual disabilities; general developmental disorders; and Serious behavioural or personality disorders); Students with specific learning difficulties; Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD); | ||

| + | |||

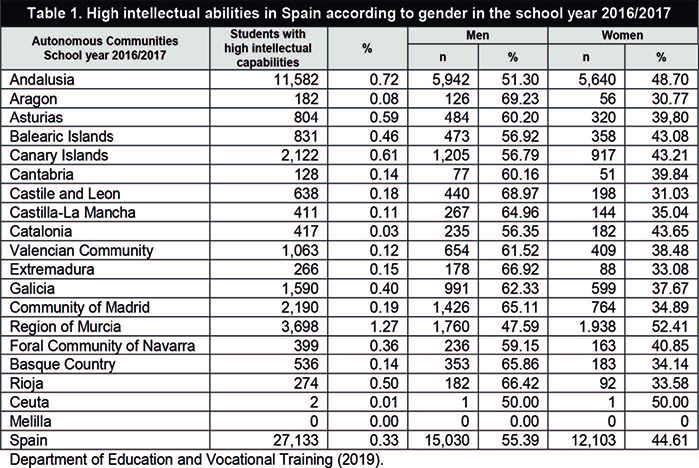

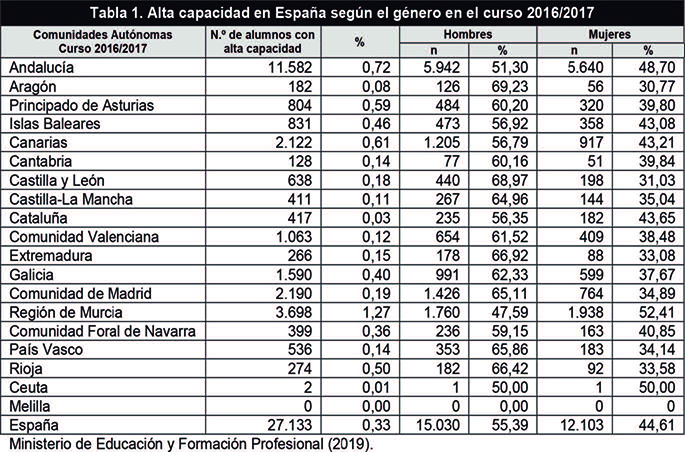

| + | Students with high intellectual abilities; Students joining the educational system late; and Students with needs due to personal conditions or school history (MECD, 2013). Pupils with high intellectual capacities form part of the SSESN, and they made up 4.23% of this group in school year 2016/17, the latest year with detailed data available for non-university teaching on the web site of the Ministry of Education and Professional Development. In contrast, gifted pupils make up 0.33% of the general, non-university school population (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2019). Various studies have indicated the percentage of highly able students at around 3% of the school population (Almeida & Oliveira, 2010; Castro, 2004; López, Beltrán, López, & Chicharro, 2000). This proportion in non-university education represents 27,133 pupils with high intellectual capacities in the various Autonomous Communities, 15,030 boys and 12,103 girls (Table 1). | ||

| + | |||

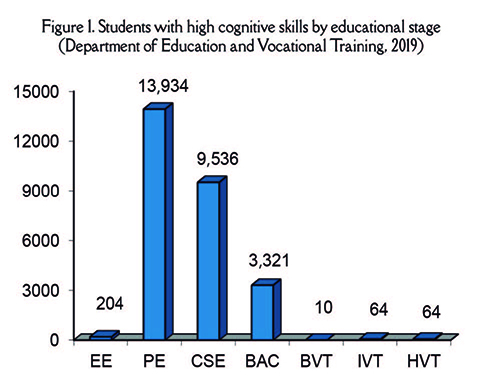

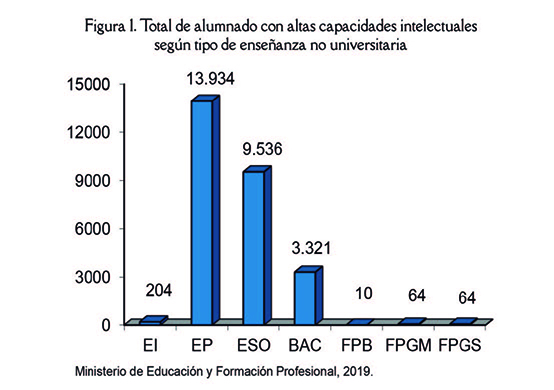

| + | Figure 1 shows the distribution of pupils with high cognitive skills along the different non-university educational stages: Early education (EE), Primary Education (PE), Compulsory Secondary Education (CSE), Baccalaureate (BAC): non-compulsory further education normally between 16 and 18 years of age), Basic Vocational Training (BVT), Intermediate Vocational Training (IVT), and Higher Vocational Training (HVT). | ||

| + | |||

| + | As Figure 1 shows, most students with high cognitive skills, 13,934 are found in primary education, followed by compulsory secondary education with 9,536 students. It is surprising to note the existence of 10 gifted students in basic vocational training as this type of schooling is aimed at trying to keep students in the educational system and to ensure they acquire basic skills in order to be able to enter the labour market. In other words, it is directed towards students with serious risks of leaving the education system early without any qualifications. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This Table and Figure give us part of the reasoning behind our study; the low prevalence of cases detected (0.33% in Spain as a whole), the small proportion of highly intellectually able students in comparison with the total SSESN (4.2% of the total), and the predominance of boys over girls in the national figures (55.4% versus 44.6%). In addition, primary education is the educational stage in which diagnostic processes are preferentially given, translating to rich periods of learning and development. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Along with that data, another reason for this article is the need to offer highly able students inclusive and multidimensional educational responses, including students with high intellectual abilities (Almeida & Oliveira, 2010; Callahan, 1998; Gagné, 2008; Gobierno de la Región de Murcia, 2018; Muñoz & Espiñeira, 2010; Prieto & Ferrando, 2016; Renzulli & Gaesser, 2015; Sastre, 2014; Tourón, 2010). It is essential to individualise their teaching and learning, requiring ‘teaching, family and social support in order to draw out their abilities and thus develop educational processes which are adapted to their needs, interests and motivations’ (García, 2018: 133). The LOMCE considers that ‘all students have talent, but the nature of this talent is different for different people. Consequently, the education system must have the necessary mechanisms to recognise and stimulate this talent. The recognition of this diversity of student abilities and expectations is the first step towards the development of an educational structure which addresses different trajectories’ (MECD, 2013: 97858). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because of that, planning modified educational responses for these students is vital, as is avoiding limitations when implementing it. These limitations sometimes come from the use of ‘age’ as grouping criteria for pupils, from the distribution of specific resources to schools with lower capacity students and students with learning difficulties. They may come from a lack of connection between diagnosis and educational intervention, from the scarcity of educational psychology resources currently in schools or poor teacher training about high intellectual abilities. They may also come from the use of general and specific methodologies, specific counselling with families, awareness on the part of educational authorities, or attitudes of rejection and prejudice towards this group (Jiménez, 2010; Jiménez & Baeza, 2012; Renzulli & Gaesser, 2015; Tourón, 2008; Veas & al., 2018). At times, there is also a gap in the foundation of current educational practice with these students, they are considered more of an extra rather than an extension, which is why it is essential to expand or to compact the study plans (García, 2018). At the same time, especially when identification rates are very low, it would be important to pay more attention to high ability students who do not achieve high levels of academic performance, which is what teachers value most. Some research has noted underachievement of gifted students as well as the difficulties teachers can have identifying giftedness when students also present some difficulties at a cognitive, emotional or behavioural level, or when they belong to disadvantaged social groups (Borland & Wright, 2000; Ecker-Lyster & Niileksela, 2017; Freeman, 1995; Peters, Grager-Loidl, & Supplee, 2000). | ||

| + | |||

| + | These aspects justify the development of educational responses for students with high intellectual abilities and in particular, enrichment programmes during school time. At the same time these programs must have an impact on students’ personal and academic situations. In the words of San (2016), we find little research analysing the true benefits of these educational programs and they are centred on extracurricular enrichment programs (Sastre & al., 2015). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====2. Materials y methods==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.1. Participants | ||

| + | |||

| + | The participants were students in the 2nd to the 6th years of primary education (PE), aged between 7 and 12 years old. They were divided into three subgroups: the Experimental Group (EG), made up of 9 highly intellectually able students in a single school in the province of Albacete who had been diagnosed by school counselling services; Control Group 1 (CG1), made up of 27 students, three students for each member of the experimental group from the same class, therefore classmates of the highly able students; and Control Group 2 (CG2), made up of 9 highly intellectually able students from different schools in the autonomous community of Castilla-La Mancha who had been diagnosed by school counselling services. The students in both control groups were selected using criteria such as being at the same educational level, sex, and similar school performance at the beginning of the year. Between them, they only differed in IQ scores, sex (due to sample availability issues), and in repeating a school year, as we were unable to find a student for control group 2 with high abilities, who had repeated a school year and who was in the 4th year of primary education. Students in both control groups did not participate in the enrichment program. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This research was conducted at a Spanish school in the province of Albacete (in Castilla-La Mancha). It is a public school in an urban environment with 622 students including the 9 students diagnosed as highly intellectually able. In the school 1.45% of the students have high intellectual abilities, which is higher than the mean of 0.11% for Castilla-La Mancha and 0.33% for Spain (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2019). Seven of the 9 identified cases of high intellectual abilities were boys (77.8%). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.2. Variables | ||

| + | |||

| + | The variables in this study were: 1) school year, from the 2nd to the 6th year of primary education, bearing in mind whether the student had repeated a school year; 2) student sex; 3) School performance; the Spanish system evaluates using a scale from 1 to 10. Scores of 1 to 4 are considered fails, a score of 5 is a pass, 5 & 6 are good, 7 & 8 are very good, and 9 & 10 are outstanding, initial evaluations were done at the beginning of the school year and at the end of the school year in June at the same time as students’ final evaluations; and 4) Intelligence Quotient (IQ), established by administering one of the Weschler Intelligence Scales for Children (WISC-IV or WISC-V). | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to these variables the sample characteristics of each group was as follows: (i) Experimental Group (EG): 1 student in the 2nd year of primary education, 1 in the 3rd year, 3 in the 4th year, 1 in the 5th year and 3 in the 6th year; 7 boys and 2 girls; 1 student with a passing grade, 1 good, 3 very good and 4 outstanding; 1 out of the nine had repeated a school year; IQs ranged between 130 and 144. (ii) Control Group 1 (CG1): 3 students in the 2nd year, 3 in 3rd year, 9 in 4th year, 3 in 5th year and 9 in 6th year; 16 boys and 11 girls; 3 with passing grades, 3 good, 9 very good and 12 outstanding; 3 of the 27 had repeated a school year; IQs ranged between 84 and 125. These variables were selected proportional to the characteristics of the experimental group, with 3 students in the control group for every student in the experimental group. (iii) Control Group 2 (CG2): 1 student in 2nd year, 1 in 3rd year, 3 in 4th year, 1 in 5th year and 3 in 6th year; 7 boys and 2 girls; 1 student with a passing grade, 1 good, 3 very good and 4 outstanding; none of the students had repeated a school year; IQs ranged from 130 to 138. The characteristics were similar to the experimental group except that none of the students in CG2 had repeated a school year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our study examined child adaptation; ‘the mix of factors that combine in the ability of an individual to integrate and function in their surroundings, taking into account the different characteristics of those surroundings and changing conditions that may occur requiring them to readjust to new circumstances’ (García, 2018: 139). Some research has noted difficulties associated with, for example, speed in learning leading to dead time and demotivation, a rich, broad vocabulary that may trigger rejection by teachers or peers, boredom due to repetition and routine, high expectations for themselves and others, a taste for learning independently and alone, low tolerance for frustration, lack of acceptance when they take on a leadership role, preferring to interact with adults, disconcerting or persistent questions, concern about social topics that are not appropriate for their chronological age, excessive motor restlessness, asynchronous development, and a strong sense of justice (García, 2018; Jiménez, 2010; Sainz & al., 2015). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.3. Instruments | ||

| + | |||

| + | Class record: this collects information related to the school year, sex, school performance, repetition of school years, and IQ scores. | ||

| + | |||

| + | TAMAI: Multifactorial Self-evaluation test of child adaptation: This test evaluates the following dimensions: general maladaptation, personal maladaptation, school maladaptation, social maladaptation, family dissatisfaction, dissatisfaction with siblings, parental educational qualifications, educational discrepancies, pro-image and contradictions (Hernández-Guanir, 2015). In this study we used General Maladaptation (GM) which looks at an individual’s lack of adaptation both with themselves and with their surroundings. In the TAMAI this is produced from the total of the three other types of maladaptation, personal, school and social. Personal Maladaptation (PM) is defined as the level of maladjustment that an individual has with themselves as well as with their general surroundings, including individual difficulties accepting reality as it is; School Maladaptation (SM) looks at dissatisfaction and inappropriate or disruptive behaviour at school, and is related to personal and social maladaptation; and Social Maladaptation (SoM) which includes the level of difficulty and problems in social interactions due to reduced social relationships, lack of social control, not considering others or established norms, and attitudes of suspicion and social distrust. As these dimensions evaluate maladaptation, low scores mean better adaptation and high scores mean more maladaptation. It is worth noting the reliability of the results, with indices above .85 for Cronbach’s alpha and the split-half method, along with appropriate indices of factorial validity (Hernández-Guanir, 2015). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Horizontal Enrichment Program for highly able students: this is a program carried out during school hours through three weekly sessions (two outside the class and one in the class group) throughout school year 2017/18. The activity areas are: linguistic, scientific, socio-emotional and artistic. The activities for each area are broad and include a wide range of individual resources such as mentors and specialists in various knowledge areas, making use of school families’ jobs. Materials principally include ITC and bibliographic resources with a breadth of reasoning for each of the activity areas. In terms of ITC, students use their own tablets through which they begin to use Web 2.0 tools (such as Padlet, Socrative, Edpuzzle, Kahoot! and Genially) and other programs which are valid for enrichment tasks (such as Geogebra and Pixton), but always in connection to the ordinary curriculum. The use of technological resources for teaching goals with highly able students is well supported (Besnoy, Dantzler, & Siders, 2012; Martínez, Sábada, & Serrano-Puche, 2018; Palomares, García, & Cebrián, 2017; Román, 2014; Sacristán, 2013), and demands specific teacher training in this field (Díez, 2012; González, 2016; Pereira, Fillol, & Moura, 2019; Rodríguez-García, Martínez, & Raso, 2017; Santoveña-Casal & Bernal-Bravo, 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.4. Procedures | ||

| + | |||

| + | The TAMAI was applied in September (pre-test) and June (post-test) during the 2017/18 school year to both the experimental and control groups. Between those two points in time the students in the experimental group participated in an enrichment program with three sessions a week. During the study, written authorisation was obtained from the Educational Inspection Service, the administrations in the participating schools and the families of students selected to participate. School performance was recorded at the two points in time and teachers of all three groups of students were asked to complete a record sheet on which they indicated each student’s overall academic performance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====3. Results==== | ||

| + | |||

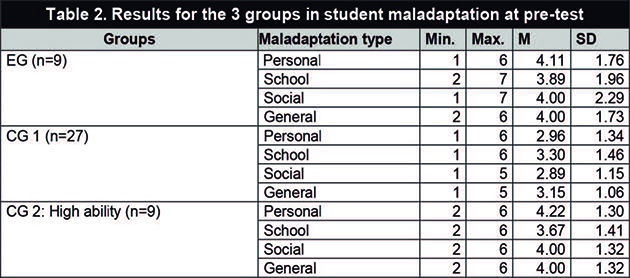

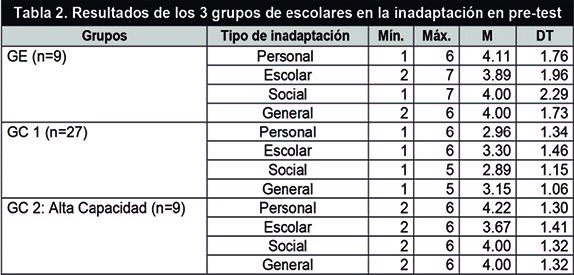

| + | Table 2 shows the results in the maladaptation dimensions and general maladaptation for the three groups at pre-test. In addition to the mean and standard deviation, it gives the range (minimum and maximum). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The data in Table 2 shows higher pre-test means in the experimental group and control group 2 than in control group 1 in all dimensions, especially in personal, social and general maladaptation. Assessing the statistical significance of these differences (F-ANOVA), we found statistically significant differences in the PM dimension (F(2,42)=3.86, p<.05), but we did not find significance in the SoM dimension (F(2,42)=3.09, p=.06). No statistically significant differences were found in the SM dimension or in general maladaptation. In the PM dimension, following post hoc tests comparing the three groups (Bonferroni test) there were no significant values in comparisons between the groups. | ||

| + | |||

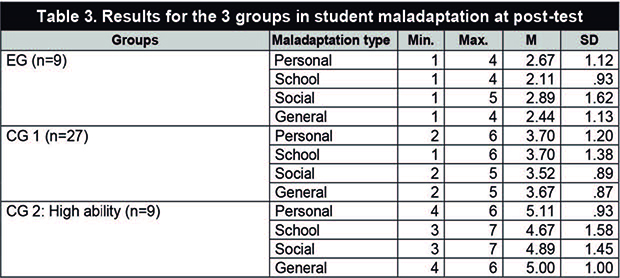

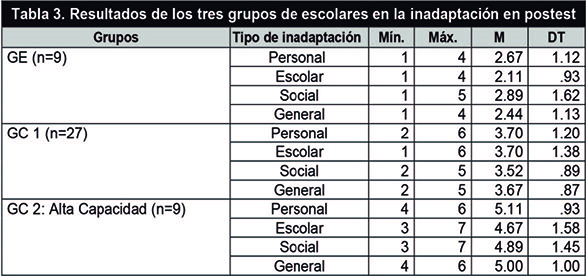

| + | Table 3 gives the results for the three groups of students for maladaptation dimensions in the post-test phase. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Table 3 we see that the experimental group means were lower than both control groups, and lower than the mid-point of 4 on the 7-point scale used. The means of both control groups were notably higher than in the pre-test, especially in control group 2, with means of 5.11 in personal maladaptation, 4.67 in school maladaptation, 4.89 in social maladaptation, and 5.00 in general maladaptation. This suggests an increase in perceived maladaptation levels in students without any educational response modified for their strengths, interests and needs. Looking at the differences in means between the three groups (F-ANOVA), we found statistically significant differences in all of the maladaptation dimensions, as well as in general maladaptation scores. The values were: PM (F(2,42)=10.50. p<.001), SM (F(2,42)=8.36, p<.001), SoM (F(2,42)=6.99, p<.001) and General (F(2,42)=16.17, p<.001). Following the Bonferroni test for post hoc analysis we found a statistically significant difference between the experimental group and control group 2 in PM (t=–2.44, p<.001). In SM there were statistically significant differences between the experimental group and control group 1 (t=–1.59, p<.05), and control group 2 (t=–2.56, p<.001). In the SoM dimension we only found statistically significant differences between the experimental group and control group 2 (t=–3.99, p<.001), while in the general dimension there were statistically significant differences between the experimental group and control group 1 (t=–1.57, p<.05) and control group 2 (t=–2.56, p<.001). There were also statistically significant differences between the two control groups in social maladaptation CG1<CG2 (t=–1.37, p<.05), and general maladaptation GC1<GC2 (t=–1.33, p<.01). | ||

| + | |||

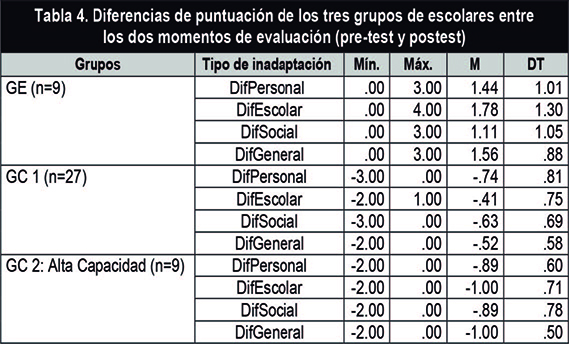

| + | In order to see the differences between the three groups’ results comparing pre-test and post-test, Table 4 shows the differences in scores between the two time-points (positive when pre-test scores are higher; high scores mean more maladaptation). | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are statistically significant differences between the three test groups after calculating the differences between the pre-test and the post-test scores Personal (F(2,42)=26.49, p<.001); School (F(2,42)=27.22, p<.001); Social (F(2,42)=19.27, p<.001) and General (F(2,42)=44.86, p<.001). Looking at the differences between groups, with the Bonferroni test, in the four dimensions there is a consistent pattern of statistically significant values; the experimental group always scores higher than the other two groups, indicating that they improve on negative evaluations at post-test. No statistically significant differences were found between control group 1 and control group 2, the highly able children without intervention. The results for each dimension are as follows Personal: EG>CG1 (t=2.19, p<.001 and EG>CG2 (t=2.33, p<.001); School: EG>CG1 (t=2.19, p<.001) and EG>CG2 (t=2.78, p<.001), Social: EG>CG1 (t=1.74, p<.001) and EG>CG2 (t=2.00. p<.001); General: EG>CG1 (t=2.07, p<.001) and EG>CG2 (t=2.56, p<.001). These differences and significance were replicated using repeated measures ANOVA and eta partial square ranged from .48 (Social) to .68 (General). | ||

| + | |||

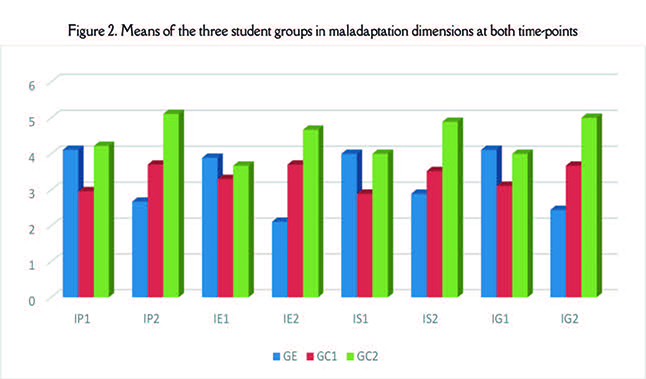

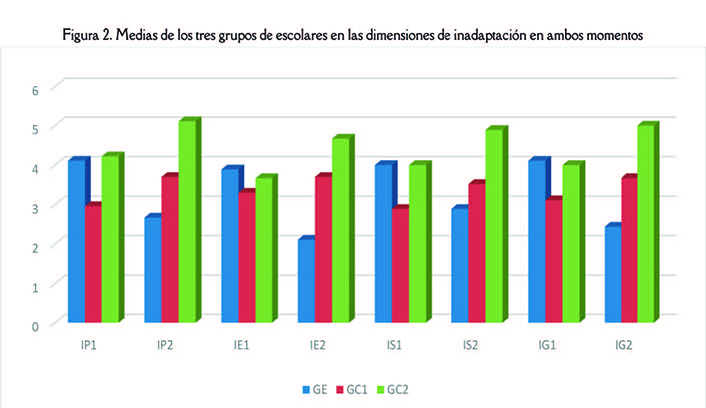

| + | Figure 2 gives a graphic comparison using the means from the experimental and control groups for the maladaptation dimensions at the two time-points (1: pre-test, 2: post-test). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Figure 2 it is especially interesting to see the significant fall in mean scores for each maladaptation area in the experimental group, falling below the means of the two control groups in the post-test. The values for control group 1 stayed more or less stable over the two time-points, however the scores for control group 2 increased from one time-point to the next. Finally, it is important to note changes in students’ school performance. In the experimental group, 4 students exhibited improved performance (one from passing to good, another one from good to very good and two from very good to outstanding); none of the students in this group demonstrated worse performance at the second time-point. In control group 1, 3 students performed better at post-test than pre-test (one from very good to outstanding, the other 2 from good to very good), with no students demonstrating worse performance at the second time-point. In control group 2, none of the students improved their performance between pre- and post-test, while one student went from outstanding to very good. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====4. Discussion and conclusions==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Educational processes must move away from homogeneous positions in which the same curriculum is transmitted to all students in the same conditions. The diversity in the classroom includes highly intellectually able students. This is a group of students with visibility problems in the classroom, which is reflected in the rates of identification, 0.11% in Castilla-La Mancha and 0.33% nationally, which are very low compared to the supposed international rates which fall between 3% and 5% of students being highly intellectually able (Almeida & Oliveira, 2010; López, Beltrán, López, & Chicharro, 2000). These students ‘are a natural part of human diversity and need to be educated in equitable schools with and for all, that can encourage excellence’ (Jiménez & García, 2013, 22). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The educational intervention processes for these students usually happen outside school hours. Despite that, the inclusion of specific activities in school time is necessary for an integrated response that would help them make the most of their skills (Almeida & Oliveira, 2010; Hernández & Gutiérrez, 2014; Mandelman, Tan, Aljughaiman, & Grigorenko, 2010). In this study we have seen that the enrichment program for highly able students during school hours helped them improve their adaptation in general and on a personal, school and societal level, with some of the students even improving their school performance. We can conclude from our data that distinct educational attention, catering to the high intellectual abilities of some of these students, will encourage their adaptation and learning in school contexts, compared to their high-ability peers whose educational needs are not specifically addressed (García & Jiménez, 2016; Kim, 2016; Lee, Olszewski-Kubilius, & Peternel, 2010; Obergriesser & Stoeger, 2015; Renzulli, 2012; Sainz & al., 2015; Walsh & al., 2012; Wu, 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Given the low rate of identification of gifted or highly able students it may be time to rethink how we identify them. Borland and Wright (2000) recommended that for students in disadvantaged groups, more use should be made of observational methodologies and portfolios of work rather than formal psychological tests. In these cases, it may be useful to work with computer and internet-based tools as some highly able students may not exhibit their capabilities in class or in their interactions with teachers, but rather in individual tasks or tasks outside the classroom (Marcos, 2014). Technology may also help students become motivated in their learning and school tasks which they often find repetitive, and it may also ease common communication difficulties with teachers (Freeman, 1995). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In short, work must be done on inclusion and academic success of highly able students in school (Veas & al., 2018). The data lead us to conclude that improving these students’ inclusion and adaptation is possible and that diversity can and must be addressed during school hours, especially using emerging technologies as learning resources as that would provide individualised speeds, processes and content for learning (Besnoy, Dantzler, & Siders, 2012). Human potential is inherent in an individual and its realisation depends on the person’s environment, bringing it out is an educational imperative. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Funding agency | ||

| + | |||

| + | This work has had the support of the Pedagogy Department and the Faculty of Education of Albacete of the UCLM (Spain) and the Institute of Education of the University of Minho (Portugal). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244-en018.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244-en019.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244-en020.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244-en021.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244-en022.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244-en023.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====References==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Almeida, L., & Oliveira, E. (2010). Los alumnos con características de sobredotación: La situación actual en Portugal. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 13(1), 85-95. https://bit.ly/2C36Hvh | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besnoy, K.D., Dantzler, J.A., & Siders, J.A. (2012). Creating a digital ecosystem for the gifted education classroom. Journal of Advanced Academics, 23(4), 305-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X12461005 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Borland, J.H., & Wright, L. (2000). Identifying and educationg poor and under-represented gifted students. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Monks, R.J. Sternberg, & R.F. Subotnik (Eds.), International handbook of giftedness and talent (pp. 587-594). New York: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008043796-5/50041-3 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Callahan, C.M. (1998). Lessons learned from evaluating programs for the gifted. Promising practices and practical pitfalls. Educación XXI, 1, 53-71. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.1.1.397 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Díez, E.J. (2012). Modelos socioconstructivistas y colaborativos en el uso de las TIC en la formación inicial del profesorado. Revista de Educación, 358, 175-196. https://doi.org/10-4438/1988-592X-RE-2010-358-074 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ecker-Lyster, M., & Niileksela, Ch. (2017). Enhancing gifted education for underrepresented students: Promising recruitment and programming strategies. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 40(1) 79-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353216686216 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Freeman, J. (1995). Gifted children growing up. Dondon: Cassell Educational Limited. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203065587 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gagné, F. (2008). Talent development: Exposing the weakest link. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 240, 203-220. https://bit.ly/2ICyMiH | ||

| + | |||

| + | García, R. (2018). La respuesta educativa con el alumnado de altas capacidades intelectuales: funcionalidad y eficacia de un programa de enriquecimiento curricular. Sobredotação, 15(2), 131-152. https://bit.ly/2tH4TmJ | ||

| + | |||

| + | García, R., & Jiménez, C. (2016). Diagnóstico de la competencia matemática de los alumnos más capaces. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 34(1), 17, 205-219. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.34.1.218521 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gobierno de la Región de Murcia (Ed.) (2018). Talleres de enriquecimiento extracurricular para alumnos con altas capacidades. https://bit.ly/2SquoCL | ||

| + | |||

| + | González, M. (2016). Formación docente en competencias TIC para la mediación de aprendizajes en el Proyecto Canaima Educativo. Telos, 18(3), 492-507. https://bit.ly/2Tfj6FV | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hernández, D., & Gutiérrez, M. (2014). El estudio de la alta capacidad intelectual en España: Análisis de la situación actual. Revista de Educación, 364, 251-272. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2014-364-261 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hernández-Guanir, P. (2015). Test autoevaluativo multifactorial de adaptación infantil. Madrid: TEA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jiménez, C. (2010). Diagnóstico y educación de los más capaces. Madrid: Pearson. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jiménez, C., & Baeza, M.A. (2012). Factores significativos del rendimiento excelente: PISA y otros estudios. Ensaio, 20(77), 647-676. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-40362012000400003 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jiménez, C., & García, R. (2013). Los alumnos más capaces en España. Normativa e incidencia en el diagnóstico y la educación. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 24(1), 7-24. https://doi.org/10.5944/reop.vol.24.num.1.2013.11267 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kim, M. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of enrichment programs on gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 60(2), 102-116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986216630607 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lee, S.-Y., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Peternel, P. (2010). Achievement after participation in a preparatory program for verbally talented students. Roeper Review, 32(3), 150-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2010.485301 | ||

| + | |||

| + | López, B., Beltrán, M.T., López, B., & Chicharro, D. (2000). Alumnos precoces, superdotados y de altas capacidades. Madrid: Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo Educativo. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mandelman, S.D., Tan, M., Aljughaiman, A.M., & Grigorenko, E.L. (2010). Intelectual gifteness: Economic, political, cultural and psychological considerations. Learning and Individual Differences, 20, 286-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.04.014 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Martínez, M.C., Sádada, C., & Serrano-Puche, J.S. (2018). Desarrollo de competencias digitales en comunidades virtuales: Un análisis de ‘ScolarTIC’. Prisma Social, 20, 129-159. https://bit.ly/2U7OUKn | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional (Ed.) (2019). Datos estadísticos no universitarios. https://bit.ly/2XnLKUD | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (2013). Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 10 de diciembre de 2013, 295, 97858?97921. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Muñoz, J.M., & Espiñeira, E.M. (2010). Plan de mejoras fruto de la evaluación de la calidad de la atención a la diversidad en un centro educativo. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 28(2), 245-266. https://bit.ly/2T5zzxu | ||

| + | |||

| + | Obergriesser, S., & Stoeger, H. (2015). The role of emotions, motivation, and learning behavior in underachievement and results of an intervention. High Ability Studies, 26(1), 167-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2015.1043003 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Palomares, A., García, R., & Cebrián, A (2017). Integración de herramientas TIC de la Web 2.0 en Sistemas de Administración de Cursos (LMS) tipo Moodle. In R. Roig (Ed.), Investigación en docencia universitaria. Diseñando el futuro a partir de la innovación educativa (pp. 980-990). Barcelona: Octaedro. https://bit.ly/2SZbWXk | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pereira, S., Fillol, J., & Moura, P. (2019). Young people learning from digital media outside of school: The informal meets the formal. [El aprendizaje de los jóvenes con medios digitales fuera de la escuela: De lo informal a lo formal]. Comunicar, 58, 41-50. https://doi.org/10.3916/C58-2019-04 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Peters, W.A, Grager-Loidl, H., & Supplee, P. (2000). Underachievemnt in gifted children and adolescents: Theory and practice. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Monks, R.J. Sternberg, & R.F. Subotnik (Eds.), International Handbook of giftedness and talent (pp. 609-620) (2nd ed.). New York: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008043796-5/50009-7 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Prieto, M.D., & Ferrando, M. (2016). New Horizons in the study of High Ability: Gifted and talented. Anales de Psicología, 32(3), 617-620. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.259301 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Renzulli, J.S. (2012). Reexamining the role of gifted education and talented development for the 21st century: A four?part theoretical approach. Gifted Child Quarterly, 56(3), 150?159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986212444901 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Renzulli, J.S., & Gaesser, A. (2015). Un sistema multicriterial para la identificación del alumnado de alto rendimiento y de alta capacidad creativo-productiva. Revista de Educación, 368, 96-131. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2015-368-290 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rodríguez-García, A.M., Martínez, N., & Raso, F. (2017). La formación del profesorado en competencia digital: clave para la educación del siglo XXI. Revista Internacional de Didáctica y Organización Educativa, 3(2), 46-65. https://bit.ly/2tDuoWg | ||

| + | |||

| + | Román, M. (2014). Aprender a programar ‘apps’ como enriquecimiento curricular en alumnado de alta capacidad. Bordón, 66(4), 135-155. https://doi.org/10.13042/bordon.2014.66401 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sacristán, A. (2013). Sociedad del conocimiento, tecnología y educación. Madrid: Morata. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sainz, M., Bermejo, M.R., Ferrándiz, C., Prieto, M.D., & Ruíz, M.J. (2015). Cómo funcionan las competencias socioemocionales en los estudiantes de alta habilidad. Aula: Revista de Pedagogía de la Universidad de Salamanca, 21, 33-47. https://doi.org/10.14201/aula2015213347 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sak, U. (2016). EPTS Curriculum Model in the Education of Gifted Students. Anales de Psicología, 32(3), 683-694. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.259441 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Santoveña-Casal, S. & Bernal-Bravo, C. (2019). Exploring the influence of the teacher: Social participation on Twitter and academic perception. [Explorando la influencia del docente: Participación social en Twitter y percepción académica]. Comunicar, 58, 75-84. https://doi.org/10.3916/C58-2019-07 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sastre, S. (2014). Intervención psicoeducativa en la alta capacidad: funcionamiento intelectual y enriquecimiento extracurricular. Revista de Neurología, 58, 89-98. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.58s01.2014030 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sastre, S., Fonseca, E., Santarén, M., & Urraca, M.L. (2015). Evaluation of satisfaction in an extracurricular enrichment program for high-intellectual ability participants. Psicothema, 27(2), 166-173. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.239 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tourón, J. (2008). La educación de los más capaces: un reto educativo y social. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 240, 197-202. https://bit.ly/2EwbXZQ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tourón, J. (2010). El desarrollo del talento y la promoción de la excelencia: Exigencias de un sistema educativo mejor. Bordón, 62(3), 133-149. https://bit.ly/2Ebvsph | ||

| + | |||

| + | Veas, A., Castejón, J.L., O´Reilly, C., & Ziegler, A. (2018). Mediation analysis of the relationship between educational capital, learning capital, and underachievement among gifted secondary school students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353218799436 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Walsh, R.L., Kemp, C.R., Hodge, K.A., & Bowes, J.M. (2012). Searching for evidence-based practice: A review of the research on education interventions for intellectually gifted children in the early childhood years. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(2), 103-128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353212440610 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wu, E. (2013). Enrichment and acceleration: Best practice for the gifted and talented. Gifted Education Press Quarterly, 27(2), 1-8. https://bit.ly/2EvLdbH | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_en"></span>[[#article_es|Click to see the English version (EN)]]</span> | <span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_en"></span>[[#article_es|Click to see the English version (EN)]]</span> | ||

| − | + | ==== Resumen ==== | |

| + | |||

| + | Este trabajo apunta la reducida tasa de alumnado con características de superdotación o altas capacidades identificados formalmente en España tomando los referenciales internacionales. Este alumnado no es debidamente identificado, entonces también se anticipa la falta de respuestas educativas específicas para estos escolares con altas capacidades. Intentando contrariar esta tendencia, este artículo presenta un programa de enriquecimiento aplicado a un grupo de alumnos y alumnas con altas capacidades intelectuales durante el curso académico de 2017/18 a lo largo de tres sesiones semanales en horario escolar y donde las tecnologías emergentes tienen una importancia clave en el desarrollo del mismo. En el plano experimental, se tomó un grupo experimental de escolares con altas capacidades y dos grupos de control, uno conformado por alumnado con altas capacidades que no reciben respuestas educativas específicas y otro constituido por un grupo de escolares regulares en términos de capacidades. Los resultados muestran que la implementación de respuestas educativas específicas mejora los niveles de adaptación infantil y, en algunos casos, su rendimiento escolar. Se discuten estos datos en una tentativa de recomendación de programas de enriquecimiento integrados en las clases como respuesta educativa apropiada a los escolares con superdotación o altas capacidades. La atención a la diversidad de todo el alumnado en las aulas es posible, por ejemplo, recurriendo a las TIC, favoreciendo la inclusión educativa del alumnado con altas capacidades. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Media:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244_ov.pdf|<span style="color:#0645AD; font-weight: bold">Descarga aquí la versión PDF</span>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 1. Introducción ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | La Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa (LOMCE) de España, incluye bajo el término de alumnado con necesidades específicas de apoyo educativo (ACNEAEs), la siguiente tipología de escolares: alumnado con necesidades educativas especiales (ACNEEs, estudiantes con discapacidad auditiva, motora, intelectual o visual; trastorno generalizado del desarrollo; y trastornos graves de la conducta y de la personalidad); alumnado con dificultades específicas de aprendizaje; alumnado con trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH); alumnado con altas capacidades intelectuales; alumnado incorporado tarde al sis-tema educativo; y alumnado con necesidades por condiciones personales o de historia escolar (MECD, 2013). Así, los alumnos y alumnas con altas capacidades intelectuales forman parte de los AC-NEAEs. Dentro de este grupo de alumnos, constituyen un 4,23% para el curso 2016/2017, último del que se disponen de datos detallados para enseñanzas no universitarias en la página web del Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. Por el contrario, en relación a la población total de alumnado escolarizado para enseñanzas no universitarias, los alumnos/as con altas capacidades suponen un 0,33% (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Diferentes investigaciones señalan alrededor del 3% la tasa de alumnado con alta capacidad entre la población escolar (Almeida & Oliveira, 2010; Castro, 2004; López, Beltrán, López, & Chicharro, 2000). Este porcentaje en enseñanzas no universitarias viene representado por 27.133 escolares con altas capacidades en el conjunto de Comunidades Autónomas, 15.030 hombres y 12.103 mujeres (Tabla 1). En la Figura 1 se indica cómo se distribuyen los alumnos y alumnas con altas capacidades entre las diferentes enseñanzas no universitarias: Educación Infantil (EI), Educación Primaria (EP), Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO), Bachillerato (BAC), Formación Profesional Básica (FPB), Formación Profesional Grado Medio (FPGM) y Formación Profesional Grado Superior (FPGS). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tal y como aparece en esta Figura 1, la enseñanza de Educación Primaria es donde más alumnos y alumnas con altas capacidades aparecen señalizados, 13.934 escolares, seguida de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria con 9.536 estudiantes. Llama especialmente la atención la existencia de escolares con altas capacidades intelectuales en la Formación Profesional Básica, 10 sujetos, tipo de enseñanza dirigida a intentar garantizar la permanencia en el sistema educativo y garantizar así una capacitación básica con vistas a la integración en el mundo laboral, es decir, está encaminada a alumnado con grave riesgo de abandono temprano del sistema educativo sin ninguna cualificación de acceso al mundo laboral. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De esta tabla y figura, se deriva parte de la justificación de nuestro artículo. Es decir, la baja prevalencia de casos detectados (0,33% en el conjunto de España), la reducida proporción de las altas capacidades intelectuales en comparación al conjunto de los ACNEAEs (4,2% del total) y la predominancia de cifras de sexo masculino sobre el femenino en el panorama nacional (55,4 % y 44,6% respectivamente). Además, la Educación Primaria se conforma como la etapa educativa en la que los procesos de diagnóstico se dan de manera preferente, lo que se traduce en periodos ricos de aprendizaje y desarrollo. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Junto a estas cifras, justifica este artículo la necesidad de ofrecer al alumnado con altas capacidades respuestas educativas inclusivas y multidimensionales, incluyendo entre ellos a aquellos que presentan altas capacidades intelectuales (Almeida & Oliveira, 2010; Callahan, 1998; Gagné, 2008; Gobierno de la Región de Murcia, 2018; Muñoz & Espiñeira, 2010; Prieto & Ferrando, 2016; Renzulli & Gaesser, 2015; Sastre, 2014; Tourón, 2010). La individualización de sus procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje es esencial, demandando «apoyo docente, familiar y social para sacar a la luz sus capacidades y poder así desarrollar procesos educativos ajustados a sus necesidades, intereses y motivaciones» (García, 2018: 133). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Desde la LOMCE se considera que: «Todos los estudiantes poseen talento, pero la naturaleza de este talento difiere entre ellos. En consecuencia, el sistema educativo debe contar con los mecanismos necesarios para reconocerlo y potenciarlo. El reconocimiento de esta diversidad entre alumno o alumna en sus habilidades y expectativas es el primer paso hacia el desarrollo de una estructura educativa que contemple diferentes trayectorias» (MECD, 2013: 97858). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Debido a ello, la planificación de respuestas educativas ajustadas para este alumnado son imprescindibles, intentando evitar aquellas limitaciones para su puesta en práctica que a veces vienen derivadas por la utilización del criterio «edad» para agrupar al alumnado, la distribución de recursos específicos entre aquellos escolares de capacidades más bajas y con dificultades de aprendizaje, la falta de conexión entre diagnóstico e intervención educativa, la escasez de recursos psicopedagógicos actualizados en los centros educativos, la débil formación docente sobre altas capacidades intelectuales, la puesta en acción de metodologías generales y específicas, el asesoramiento específico a desarrollar con las familias, la concienciación por parte de las administraciones educativas, las actitudes de rechazo y prejuicios existentes hacia este colectivo, entre otras (Jiménez, 2010; Jiménez & Baeza, 2012; Renzulli & Gaesser, 2015; Tourón, 2008; Veas & al., 2018). Además, a veces existe una carencia en la fundamentación de las prácticas educativas actuales con estos escolares, consideradas más un «extra» pero no una «extensión», por lo que es fundamental complementar y compactar los planes de estudio (García, 2018). Al mismo tiempo, especialmente cuando las tasas de identificación son muy escasas, sería importante estar más atentos a aquellos escolares con altas capacidades pero que no obtienen alto rendimiento escolar, siendo este el criterio más valorado por los profesores. Alguna investigación apunta situaciones de «under-achievement» de los alumnos y alumnas superdotados y también la dificultad de los profesores para identificar su superdotación cuando presentan alguna dificultad al nivel cognitivo, emocional o de conducta, además de su pertenencia a grupos socioculturales desfavorecidos (Borland & Wright, 2000; Ecker-Lyster & Niileksela, 2017; Freeman, 1995; Peters, Grager-Loidl, & Supplee, 2000). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los aspectos señalados justifican el desarrollo de respuestas educativas para los estudiantes con altas capacidades intelectuales, en particular los programas de enriquecimiento en horario lectivo. Al mismo tiempo, es necesario que estas respuestas tengan impacto en la mejora de su situación personal y académica. En palabras de Sak (2016), nos encontramos con escasas investigaciones que analicen los verdaderos beneficios de estos programas educativos y se centran en programas de enriquecimiento extracurricular (Sastre & al., 2015). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====2. Material y métodos==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.1. Participantes | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los participantes han sido alumnos/as de 2º a 6º de Educación Primaria (EP), edades comprendidas entre los 7 y 12 años, repartidos por tres subgrupos: el grupo experimental (GE) formado por nueve escolares con altas capacidades intelectuales de un mismo centro escolar de la provincia de Albacete diagnosticados por parte de los servicios de orientación educativa; el grupo de control 1 (GC1) formado por 27 escolares, tres estudiantes por cada escolar con altas capacidades intelectuales del grupo experimental, escolarizados en la misma aula y por tanto compañeros de cada uno de estos escolares más capaces; y el grupo de control 2 (GC2) formado por nueve estudiantes con altas capacidades intelectuales de distintos centros educativos de la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla-La Mancha diagnosticados por parte de los servicios de orientación educativa. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los alumnos pertenecientes a ambos grupos de control han sido seleccionados siguiendo criterios como mismo nivel educativo, sexo y similar rendimiento escolar al inicio de curso. Entre ellos han diferido tan solo en puntuaciones de cociente intelectual (CI), en el sexo de alguno de ellos por motivos de disponibilidad de muestra y en la repetición de curso ya que no se ha encontrado un alumno del grupo de control 2 con altas capacidades, que hubiera repetido curso y estuviera escolarizado en 4º de Educación Primaria. Los alumnos de ambos grupos de control no han participado en el programa de enriquecimiento. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Esta investigación se ha contextualizado en un centro escolar español ubicado en la provincia de Albacete (Castilla-La Mancha). Este colegio es un centro público de entorno urbano con 622 estudiantes, entre ellos aparecen nueve escolares diagnosticados con altas capacidades intelectuales. Como puede observarse, en el colegio hay un 1,45% de alumnado con altas capacidades intelectuales, cifras de diagnóstico superiores a los promedios de su región, Castilla-La Mancha, con un 0,11% y de España con un 0,33% (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2019). Por otro lado, en relación al sexo, de los 9 casos identificados con altas capacidades intelectuales, siete han sido niños (77,8%). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.2. Variables | ||

| + | |||

| + | Las variables en esta investigación han sido: 1) Nivel escolar: cursos desde 2º a 6º de Educación Primaria, teniendo en cuenta la existencia o no de repetición de curso; 2) Sexo: identidad de género del alumnado; 3) Rendimiento escolar: Escala considerando Insuficiente (IS) las calificaciones de 1 a 4, Suficiente (SF) la calificación de 5, Bien (BI) la calificación de 6, Notable (NT) las calificaciones de 7 y 8, y Sobresaliente (SB) las calificaciones de 9 y 10, tomando las evaluaciones iniciales realizadas en septiembre a los estudiantes al comienzo del curso 2017-2018, y al final de curso en junio coincidiendo con las evaluaciones finales; 4) Cociente Intelectual (CI): fijada tras la administración de una de las Escalas de Inteligencia de Wechsler para Niños (WISC-IV o WISC-V). | ||

| + | |||

| + | De acuerdo a estas variables, las características de la muestra para cada uno de los grupos ha sido la siguiente: 1) Grupo experimental (GE): un alumno escolarizado en 2º de Educación Primaria (EP), uno en 3º de EP, tres en 4º de EP, uno en 5º de EP y tres en 6º de EP; siete hombres y dos mujeres; un alumno con rendimiento inicial de suficiente, uno de bien, tres de notable y cuatro de sobresaliente; uno de los nueve escolares ha repetido curso; puntuaciones de CI entre 130 y 144; 2) Grupo control 1 (GC1): tres estudiantes escolarizados en 2º de Educación Primaria (EP), tres en 3º de EP, nueve en 4º de EP, tres en 5º de EP y nueve en 6º de EP; 16 hombres y 11 mujeres; tres escolares con rendimiento inicial de suficiente, tres de bien, nueve de notable y 12 de sobresaliente; tres de los 27 escolares han repetido curso; puntuaciones de CI entre 84 y 125. Estas variables han sido seleccionadas de manera proporcional a las características distintivas del grupo experimental, un alumno de este último grupo por tres del grupo de control 1; 3) Grupo control 2 (GC2): 1 alumno escolarizado en 2º de Educación Primaria (EP), uno en 3º de EP, tres en 4º de EP, uno en 5º de EP y tres en 6º de EP; siete hombres y dos mujeres; un alumno con rendimiento inicial de suficiente, uno de bien, tres de notable y cuatro de sobresaliente; ninguno de los nueve escolares ha repetido curso; puntuaciones de CI entre 130 y 138. Las características distintas han sido similares al del grupo experimental, tan solo existe la diferencia en cuanto a la variable repetición al no aparecer ningún alumno del grupo de control 2 como repetidor de curso. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Esta investigación considera la adaptación infantil, entendida como «la conjunción de factores que inciden en la capacidad de un individuo para integrarse y desenvolverse en aquellos contextos que le rodean, teniendo presente las características distintivas de los mismos y aquellas condiciones cambiantes que pudieran surgir y que les exigirían una reacomodación a las nuevas circunstancias» (García, 2018: 139). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Existen investigaciones que remarcan dificultades asociadas a la rapidez en el aprendizaje que deriva en «tiempos muertos» y desmotivación, amplio y rico vocabulario que puede acarrear rechazo por parte del profesorado o sus iguales, aburrimiento ante la repetición y lo rutinario, elevadas expectativas hacia sí mismos y los demás, gusto por el trabajo independiente y solitario, baja tolerancia a la frustración, falta de aceptación en el ejercicio del liderazgo, preferencia por interactuar con adultos, cuestiones desconcertantes y reincidentes, preocupación por temas sociales no ajustados a su edad cronológica, excesiva inquietud motora, existencia de disincronías, o fuerte sentido de la justicia, por ejemplo (García, 2018; Jiménez, 2010; Sainz & al., 2015). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.3. Instrumentos | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hoja de registro tutorial: Con ella se ha recopilado la información relativa al curso, sexo, rendimiento escolar, repetición de curso y puntuación de CI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | • Test Autoevaluativo Multifactorial de Adaptación Infantil (TAMAI): test que evalúa las siguientes dimensiones: inadaptación general, inadaptación personal, inadaptación escolar, inadaptación social, insatisfacción familiar, insatisfacción con los hermanos, educación adecuada del padre, educación adecuada de la madre, Discrepancia educativa, Pro-imagen y Contradicciones (Hernández-Guanir, 2015). Para esta investigación, se han utilizado la inadaptación general (IG): se trata de la falta de adaptación del individuo tanto consigo mismo como con aquellos entornos en los que vive y se desenvuelve. En el TAMAI aparece tras la suma de los otros tres tipos de inadaptación que se explican a continuación: personal, escolar y social. La inadaptación personal (IP) se define tanto por el grado de desajuste que los individuos tienen consigo mismos como con el ambiente general que le rodea, incluyendo aquellas dificultades personales para aceptar la realidad tal y como es; inadaptación escolar (IE) abarca la insatisfacción y el comportamiento inadecuado o disruptivo en la escuela, teniendo relación con la inadaptación personal y social; e inadaptación social (IS) incluye el grado de dificultad y la problemática existente en las interacciones sociales derivadas de las relaciones sociales reducidas, la falta de control social, la desconsideración a los demás y a las normas establecidas y actitudes de recelo y desconfianza social. Importa señalar la confiabilidad de los resultados con índices por encima de .85 tanto en el alfa de Cronbach como en el método de partición de dos mitades y índices de validez factorial adecuados (Hernández-Guanir, 2015). | ||

| + | |||

| + | • Programa de Enriquecimiento Horizontal para Alumnos con Altas Capacidades: programa desarrollado en horario lectivo a lo largo de tres sesiones semanales durante todo el curso académico 2017/2018, dos fuera del aula y otra dentro del grupo clase. Los ámbitos de actuación que comprende son: lingüístico, científico, socio-emocional y artístico. Las actividades para cada ámbito tienen un carácter de ampliación horizontal y abarcan un amplio abanico de recursos personales, incluye mentores y especialistas en diversas áreas de conocimiento aprovechando los puestos laborales de familias del centro educativo, y materiales, principalmente utilización de las TIC y recursos bibliográficos con amplio espectro de razonamiento para cada uno de los ámbitos de actuación. Respecto al manejo de las TIC, el alumnado hace uso de sus tablets personales y mediante su utilización se les inicia al manejo de herramientas de la Web 2.0 (caso de Padlet, Socrative, Edpuzzle, Kahoot! y Genially) y otros programas informáticos válidos para tareas de enriquecimiento (caso de Geogebra y Pixton), siempre en conexión con el currículum ordinario. El empleo con fines pedagógicos de recursos tecnológicos con alumnos de altas capacidades está justificado (Besnoy, Dantzler, & Siders, 2012; Martínez, Sábada, & Serrano-Puche, 2018; Palomares, García, & Cebrián, 2017; Román, 2014; Sacristán, 2013), demandando al profesorado formación específica en este campo (Díez, 2012; González, 2016; Pereira, Fillol, & Moura, 2019; Rodríguez-García, Martínez, & Raso, 2017; Santoveña-Casal & Bernal-Bravo, 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.4. Procedimientos | ||

| + | |||

| + | La administración del TAMAI ha sido llevada a cabo en dos momentos tanto para el grupo experimental como para los grupos de control, en septiembre (pre-test) y junio (postest) del curso académico 2017/18. Además, entre ambos periodos, los escolares que forman parte del GE han participado en un programa de enriquecimiento con una periodicidad de tres sesiones semanales. En todo el proceso de investigación, se ha solicitado autorización por escrito al Servicio de Inspección Educativa, a la dirección de las escuelas participantes y a las familias del alumnado seleccionado como muestra de investigación. Por otro lado, el rendimiento escolar ha sido recogido en ambos momentos de la investigación y para los tres grupos participantes tras solicitar a sus tutores que cumplimentaran una hoja de registro en la que han tenido que señalar el rendimiento escolar en el conjunto de las áreas de aprendizaje. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====3. Resultados==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | En la Tabla 2 presentamos los resultados en las dimensiones de inadaptación y en inadaptación general para los tres grupos de escolares en pre-test. Además de la media y la desviación típica, se presenta la amplitud (mínimo y máximo). En esta Tabla 2 se observan en pre-test medias superiores del grupo experimental y del grupo de control 2 respecto al grupo de control 1 en todas las dimensiones, destacando sobre todo en inadaptación personal, social y general. Apreciando estas diferencias sobre su significancia estadística (F-anova), verificamos diferencias estadísticas en la dimensión IP (F(2,42)=3.86, p<.05), no encontrándose significancia en los valores de la dimensión IS (F(2,42)=3.09, p=.06). En la dimensión IE y general no se observan diferencias estadísticamente significativas. Por otro lado, en la dimensión IP y tras la realización de las pruebas post hoc comparando los tres grupos (test de contraste de Bonferroni) no hay valores significativos en la comparación de los grupos entre sí. | ||

| + | |||

| + | En la Tabla 3 se presentan los resultados de los tres grupos de estudiantes en las dimensiones de la inaptación en la fase de postest. | ||

| + | |||

| + | En Tabla 3 se observan medias inferiores del grupo experimental con respecto a ambos grupos de control, y siempre la media se sitúa por debajo del nivel intermedio de 4 puntos en la escala de 7 puntos utilizada. En el lado opuesto, las medias de ambos grupos de control suben sensiblemente respecto al pre-test, sobre todo en el caso del grupo de control 2 con medias de 5.11 en inadaptación personal, 4.67 en inadaptación escolar, 4.89 en inadaptación social y 5.00 en inadaptación general, sugiriendo un aumento en los niveles de inadaptación percibidos a lo largo de la escolarización de aquellos escolares sin ningún tipo de respuesta educativa ajustada a sus potencialidades, intereses y necesidades. Analizando las diferencias de medias entre los tres grupos (F-Anova), se verifican diferencias estadísticamente significativas en todas las dimensiones de inadaptación, e incluso en la puntuación general, siendo los valores: IP (F(2,42)=10.50, p<.001), IE (F(2,42)=8.36, p<.001), IS (F(2,42)=6.99, p<.001) y General (F(2,42)=16.17, p<.001). Procediendo por el test de Bonferroni para el análisis de los contrastes post hoc entre los tres grupos, se ha observado en IP una diferencia estadística entre el grupo experimental y el grupo de control 2 (t=–2.44, p<.001), en IE las diferencias son estadísticamente significativas comparando el grupo experimental con el grupo control 1 (t=–1.59, p<.05) y con el grupo control 2 (t=–2.56, p<.001), en la dimensión IS solo se verifica diferencia estadísticamente significativa comparando el grupo experimental con el grupo de control 2 (t=–3.99, p<.001), habiendo diferencia estadísticamente significativa en la dimensión general comparando el grupo experimental con el grupo control 1 (t=–1.57, p<.05 y con el grupo control 2 (t=–2.56, p<.001). A su vez, hay que añadir una diferencia estadísticamente significativa comparando los dos grupos de control entre sí en la Inadaptación Social G2<G3 (t=–1.37, p<.05) y General G2<G3 (t=–1.33, p<.01). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Para apreciar diferencias entre los resultados de los tres grupos de alumnado comparando pre-test y postest, en la Tabla 4 se presentan los resultados tomando la diferencia entre las puntuaciones en los dos momentos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | En las cuatro variables se observa una diferencia estadísticamente significativa comparando los tres grupos de escolares tras calcular la diferencia de puntuaciones entre el pre-test y el postest: Personal (F(2,42)=26.49, p<.001); Escolar (F(2,42)=27.22, p<.001); Social (F(2,42)=19.27, p<.001) y General (F(2,42)=44.86, p<.001). Analizando los contrastes entre los grupos, test de Bonferroni, en las cuatro dimensiones evaluadas se asiste siempre a un mismo patrón de valores estadísticamente significativos: el grupo experimental presenta siempre una media superior a los otros dos grupos significando que mejoran las evaluaciones negativas en el postest, no habiendo diferencias estadísticamente significativas cuando comparamos el grupo de control 1 y el grupo de control 2 de alumnado de altas capacidades sin intervención, entre sí. Así, tenemos para cada dimensión los siguientes resultados: Personal: G1>G2 (t=2.19, p<.001 e G1>G3 (t=2.33, p<.001); Escolar: G1>G2 (t=2.19, p<.001) e G1>G3 (t=2.78, p<.001), Social: G1>G2 (t=1.74, p<.001) e G1>G3 (t=2.00, p<.001); y General: G1>G2 (t=2.07, p<.001) e G1>G3 (t=2.56, p<.001). | ||

| + | |||

| + | En la Figura 2 se establece una comparativa gráfica tomando las medias entre el grupo experimental y ambos grupos de control para las áreas de inadaptación evaluadas y los dos momentos de la investigación (1: pre-test, y 2: postest). | ||

| + | |||

| + | En esta Figura 2 llama especialmente la atención lo señalado con anterioridad, la bajada significativa de las puntuaciones medias para cada área de inadaptación por parte del grupo experimental, alcanzando valores inferiores a ambos grupos de control en el postest. Los valores del grupo de control 1 se han mantenido más o menos estables en ambos momentos, sin embargo, los valores del grupo de control 2 han aumentado de un momento de la investigación a otro. Por último, importa indicar los cambios existentes en el rendimiento escolar de los alumnos entre pre-test y postest. Para el grupo experimental, han existido mejoras en el rendimiento por parte de 4 alumnos (un paso de suficiente a notable, otro de bien a notable y dos de notable a sobresaliente); del total de alumnado de este grupo, ninguno baja su rendimiento. Respecto al grupo de control 1, 3 alumnos han subido su rendimiento del pre-test al postest (uno de notable a sobresaliente, los otros dos de bien a notable), mientras que ningún alumno baja en este grupo. Por último, en relación al grupo de control 2, ningún alumno ha aumentado su rendimiento del pre-test al postest, sin embargo, un alumno ha disminuido de sobresaliente a notable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====4. Discusión y conclusiones==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los procesos educativos deberán alejarse de posiciones homogéneas en las que el mismo currículum se «transmite» a todo el alumnado en igualdad de condiciones. Entre la heterogeneidad existente en las aulas, aparecen los alumnos con altas capacidades intelectuales. Se trata de un colectivo de escolares con problemas de «visibilidad» en las aulas, reflejándose esta realidad en las cifras de diagnóstico, 0,11% en Castilla-La Mancha y 0,33% en el conjunto nacional, unas cifras bajas si atendemos a la suposición internacional de 3% a 5% de alumnos con altas capacidades intelectuales (Almeida & Oliveira, 2010; López, Beltrán, López, & Chicharro, 2000). Estos escolares «forman parte natural de la diversidad humana y precisan ser formados en una escuela equitativa con y para todos, capaz de impulsar el rendimiento excelente» (Jiménez & García, 2013: 22). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los procesos de intervención educativa para este alumnado suelen desarrollarse, mayormente, en horario extraescolar. A pesar de ello, la integración en horario lectivo de actuaciones específicas es una necesidad para una respuesta integral que permita potenciar sus capacidades (Almeida & Oliveira, 2010; Hernández & Gutiérrez, 2014; Mandelman, Tan, Aljughaiman, & Grigorenko, 2010). En esta investigación se ha observado que el programa de enriquecimiento desarrollado con los alumnos y alumnas con altas capacidades en horario lectivo les ha permitido mejorar sus niveles de adaptación a nivel personal, escolar, personal y general, incluso ha mejorado el rendimiento escolar de algunos de esos alumnos. Estos datos nos permiten concluir que una atención educativa diferenciada teniendo en cuenta las altas capacidades intelectuales de algunos escolares favorece su adaptación y aprendizaje en el contexto escolar comparando con sus colegas de altas capacidades sin atención a sus necesidades educativas (García & Jiménez, 2016; Kim, 2016; Lee, Olszewski-Kubilius, & Peternel, 2010; Obergriesser & Stoeger, 2015; Renzulli, 2012; Sainz & al., 2015; Walsh & al., 2012; Wu, 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Siendo reducida la tasa de alumnado identificados con superdotación o altas capacidades se podría repensar la metodología utilizada en su identificación. Borland y Wright (2000) recomiendan que en aquellos grupos de alumnos socioculturalmente desfavorecidos se deberían recurrir a metodologías más observacionales y portafolios de producciones y menos a los tests psicológicos formales. En estos casos, el trabajo con herramientas informáticas e Internet podría ser interesante, pues es posible que algunos estudiantes con altas habilidades no presenten sus altas capacidades en clase o en sus relaciones con los profesores, pero lo expresan en sus tareas individuales y fuera de clase (Marcos, 2014). La tecnología puede, incluso, apoyar a los alumnos a que se motiven en sus aprendizajes académicos y en las tareas escolares pues muchas veces las consideran repetitivas, atenuando también las dificultades comunicacionales frecuentes con sus profesores (Freeman, 1995). | ||

| + | |||

| + | En síntesis, es necesario trabajar la inclusión y el suceso académico de los alumnos con altas capacidades en la escuela (Veas & al., 2018). Los datos obtenidos permiten concluir que la mejora de la inclusión o adaptación de este alumnado es posible y que la atención a la diversidad puede y debe hacerse también en horario lectivo, tomando como recursos de aprendizaje destacados las tecnologías emergentes pues permiten espacios de individualización en el ritmo, procesos y contenidos de aprendizaje (Besnoy, Dantzler, & Siders, 2012). El potencial humano es inherente a la persona y su concreción dependiente de su entorno, su cultivo para sacarlo a la luz constituye un imperativo educativo. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Apoyos | ||

| + | |||

| + | Este trabajo ha contado con el apoyo del Departamento de Pedagogía y la Facultad de Educación de Albacete de la UCLM (España) y el Instituto de Educação y el CIed (Centro de Investigação em Educação), proyecto UID/CED/01661/2019 a través de fondos nacionales de FCT/ MCTES-PT, de la Universidade do Minho (Portugal). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244_ov-es018.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244_ov-es019.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244_ov-es020.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244_ov-es021.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244_ov-es022.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Garcia-Perales_Almeida_2019a-73244_ov-es023.jpg|center|px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Referencias==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Almeida, L., & Oliveira, E. (2010). Los alumnos con características de sobredotación: La situación actual en Portugal. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 13(1), 85-95. https://bit.ly/2C36Hvh | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besnoy, K.D., Dantzler, J.A., & Siders, J.A. (2012). Creating a digital ecosystem for the gifted education classroom. Journal of Advanced Academics, 23(4), 305-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X12461005 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Borland, J.H., & Wright, L. (2000). Identifying and educationg poor and under-represented gifted students. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Monks, R.J. Sternberg, & R.F. Subotnik (Eds.), International handbook of giftedness and talent (pp. 587-594). New York: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008043796-5/50041-3 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Callahan, C.M. (1998). Lessons learned from evaluating programs for the gifted. Promising practices and practical pitfalls. Educación XXI, 1, 53-71. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.1.1.397 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Díez, E.J. (2012). Modelos socioconstructivistas y colaborativos en el uso de las TIC en la formación inicial del profesorado. Revista de Educación, 358, 175-196. https://doi.org/10-4438/1988-592X-RE-2010-358-074 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ecker-Lyster, M., & Niileksela, Ch. (2017). Enhancing gifted education for underrepresented students: Promising recruitment and programming strategies. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 40(1) 79-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353216686216 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Freeman, J. (1995). Gifted children growing up. Dondon: Cassell Educational Limited. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203065587 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gagné, F. (2008). Talent development: Exposing the weakest link. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 240, 203-220. https://bit.ly/2ICyMiH | ||

| + | |||

| + | García, R. (2018). La respuesta educativa con el alumnado de altas capacidades intelectuales: funcionalidad y eficacia de un programa de enriquecimiento curricular. Sobredotação, 15(2), 131-152. https://bit.ly/2tH4TmJ | ||

| + | |||

| + | García, R., & Jiménez, C. (2016). Diagnóstico de la competencia matemática de los alumnos más capaces. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 34(1), 17, 205-219. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.34.1.218521 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gobierno de la Región de Murcia (Ed.) (2018). Talleres de enriquecimiento extracurricular para alumnos con altas capacidades. https://bit.ly/2SquoCL | ||

| + | |||

| + | González, M. (2016). Formación docente en competencias TIC para la mediación de aprendizajes en el Proyecto Canaima Educativo. Telos, 18(3), 492-507. https://bit.ly/2Tfj6FV | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hernández, D., & Gutiérrez, M. (2014). El estudio de la alta capacidad intelectual en España: Análisis de la situación actual. Revista de Educación, 364, 251-272. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2014-364-261 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hernández-Guanir, P. (2015). Test autoevaluativo multifactorial de adaptación infantil. Madrid: TEA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jiménez, C. (2010). Diagnóstico y educación de los más capaces. Madrid: Pearson. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jiménez, C., & Baeza, M.A. (2012). Factores significativos del rendimiento excelente: PISA y otros estudios. Ensaio, 20(77), 647-676. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-40362012000400003 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jiménez, C., & García, R. (2013). Los alumnos más capaces en España. Normativa e incidencia en el diagnóstico y la educación. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 24(1), 7-24. https://doi.org/10.5944/reop.vol.24.num.1.2013.11267 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kim, M. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of enrichment programs on gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 60(2), 102-116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986216630607 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lee, S.-Y., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Peternel, P. (2010). Achievement after participation in a preparatory program for verbally talented students. Roeper Review, 32(3), 150-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2010.485301 | ||

| + | |||

| + | López, B., Beltrán, M.T., López, B., & Chicharro, D. (2000). Alumnos precoces, superdotados y de altas capacidades. Madrid: Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo Educativo. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mandelman, S.D., Tan, M., Aljughaiman, A.M., & Grigorenko, E.L. (2010). Intelectual gifteness: Economic, political, cultural and psychological considerations. Learning and Individual Differences, 20, 286-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.04.014 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Martínez, M.C., Sádada, C., & Serrano-Puche, J.S. (2018). Desarrollo de competencias digitales en comunidades virtuales: Un análisis de ‘ScolarTIC’. Prisma Social, 20, 129-159. https://bit.ly/2U7OUKn | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional (Ed.) (2019). Datos estadísticos no universitarios. https://bit.ly/2XnLKUD | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (2013). Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 10 de diciembre de 2013, 295, 97858?97921. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Muñoz, J.M., & Espiñeira, E.M. (2010). Plan de mejoras fruto de la evaluación de la calidad de la atención a la diversidad en un centro educativo. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 28(2), 245-266. https://bit.ly/2T5zzxu | ||

| + | |||

| + | Obergriesser, S., & Stoeger, H. (2015). The role of emotions, motivation, and learning behavior in underachievement and results of an intervention. High Ability Studies, 26(1), 167-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2015.1043003 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Palomares, A., García, R., & Cebrián, A (2017). Integración de herramientas TIC de la Web 2.0 en Sistemas de Administración de Cursos (LMS) tipo Moodle. In R. Roig (Ed.), Investigación en docencia universitaria. Diseñando el futuro a partir de la innovación educativa (pp. 980-990). Barcelona: Octaedro. https://bit.ly/2SZbWXk | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pereira, S., Fillol, J., & Moura, P. (2019). Young people learning from digital media outside of school: The informal meets the formal. [El aprendizaje de los jóvenes con medios digitales fuera de la escuela: De lo informal a lo formal]. Comunicar, 58, 41-50. https://doi.org/10.3916/C58-2019-04 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Peters, W.A, Grager-Loidl, H., & Supplee, P. (2000). Underachievemnt in gifted children and adolescents: Theory and practice. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Monks, R.J. Sternberg, & R.F. Subotnik (Eds.), International Handbook of giftedness and talent (pp. 609-620) (2nd ed.). New York: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008043796-5/50009-7 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Prieto, M.D., & Ferrando, M. (2016). New Horizons in the study of High Ability: Gifted and talented. Anales de Psicología, 32(3), 617-620. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.259301 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Renzulli, J.S. (2012). Reexamining the role of gifted education and talented development for the 21st century: A four?part theoretical approach. Gifted Child Quarterly, 56(3), 150?159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986212444901 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Renzulli, J.S., & Gaesser, A. (2015). Un sistema multicriterial para la identificación del alumnado de alto rendimiento y de alta capacidad creativo-productiva. Revista de Educación, 368, 96-131. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2015-368-290 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rodríguez-García, A.M., Martínez, N., & Raso, F. (2017). La formación del profesorado en competencia digital: clave para la educación del siglo XXI. Revista Internacional de Didáctica y Organización Educativa, 3(2), 46-65. https://bit.ly/2tDuoWg | ||

| + | |||

| + | Román, M. (2014). Aprender a programar ‘apps’ como enriquecimiento curricular en alumnado de alta capacidad. Bordón, 66(4), 135-155. https://doi.org/10.13042/bordon.2014.66401 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sacristán, A. (2013). Sociedad del conocimiento, tecnología y educación. Madrid: Morata. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sainz, M., Bermejo, M.R., Ferrándiz, C., Prieto, M.D., & Ruíz, M.J. (2015). Cómo funcionan las competencias socioemocionales en los estudiantes de alta habilidad. Aula: Revista de Pedagogía de la Universidad de Salamanca, 21, 33-47. https://doi.org/10.14201/aula2015213347 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sak, U. (2016). EPTS Curriculum Model in the Education of Gifted Students. Anales de Psicología, 32(3), 683-694. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.259441 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Santoveña-Casal, S. & Bernal-Bravo, C. (2019). Exploring the influence of the teacher: Social participation on Twitter and academic perception. [Explorando la influencia del docente: Participación social en Twitter y percepción académica]. Comunicar, 58, 75-84. https://doi.org/10.3916/C58-2019-07 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sastre, S. (2014). Intervención psicoeducativa en la alta capacidad: funcionamiento intelectual y enriquecimiento extracurricular. Revista de Neurología, 58, 89-98. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.58s01.2014030 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sastre, S., Fonseca, E., Santarén, M., & Urraca, M.L. (2015). Evaluation of satisfaction in an extracurricular enrichment program for high-intellectual ability participants. Psicothema, 27(2), 166-173. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.239 | ||

| + | |||