| (25 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | Published in ''Underground Space'', Vol. 3 (4), pp. 310-316, 2018<br /> | ||

| + | doi: 10.1016/j.undsp.2018.09.002 | ||

==Abstract== | ==Abstract== | ||

| Line 30: | Line 32: | ||

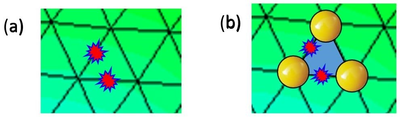

2. The threshold of failure (fracture) of each element is evaluated. This can be done via procedures based on the point-wise value of the stresses (or the strains), or using an adequate energy norm. In our work the rock has a linear elastic behavior limited by a simple Rankine crack model with a linear damage rule which has been used to define the onset of fracture at the mid-point of the element sides <span id='citeF-11'></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]]. The element damage corresponds to the largest value of the damage parameter at the different cut planes existing in a triangle. The cut plane damage is evaluated as the mean value of the damage parameter at the edges involved in such cut plane as shown in Figure [[#img-1|1]](a), were two element sides are damaged. | 2. The threshold of failure (fracture) of each element is evaluated. This can be done via procedures based on the point-wise value of the stresses (or the strains), or using an adequate energy norm. In our work the rock has a linear elastic behavior limited by a simple Rankine crack model with a linear damage rule which has been used to define the onset of fracture at the mid-point of the element sides <span id='citeF-11'></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]]. The element damage corresponds to the largest value of the damage parameter at the different cut planes existing in a triangle. The cut plane damage is evaluated as the mean value of the damage parameter at the edges involved in such cut plane as shown in Figure [[#img-1|1]](a), were two element sides are damaged. | ||

| − | 3. A collection of DE is introduced within the FE that have exceeded the failure threshold. In our work this occurs when element damage reaches a 95% of the threshold value. At this moment, the continuum region previously occupied by the damaged element is modelled with a collection of DE created at the element nodes and the damaged elements are removed Figure[[#img-1|1]](b). The radius of the new DE is defined as the maximum possible to avoid collisions with other DE. The mass of the system remains constant because 1/3 of the element mass goes to each DE created at the element nodes. | + | 3. A collection of DE is introduced within the FE that have exceeded the failure threshold. In our work this occurs when element damage reaches a 95% of the threshold value. At this moment, the continuum region previously occupied by the damaged element is modelled with a collection of DE created at the element nodes and the damaged elements are removed Figure [[#img-1|1]](b). The radius of the new DE is defined as the maximum possible to avoid collisions with other DE. The mass of the system remains constant because 1/3 of the element mass goes to each DE created at the element nodes. |

<div id='img-1'></div> | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| Line 40: | Line 42: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | 4. A two-stage time integration scheme is used to solve the contact between the DE and the FE mesh. For the DE an explicit time integration scheme is used to record the impulse between <math display="inline">t</math> and <math display="inline">t + \Delta t</math> <span id='citeF-12'></span><span id='citeF-13'></span>[[#cite-12|[12,13]]]. The impulse found is used in the FE mesh to evaluate the displacements, velocities and accelerations and also at the DE at the same time period via an implicit time integration scheme. The introduction of additional DE regions on the FE mesh evolves in time accordingly to the evolution of the stress field in the domain. For blast problems the transition of the FE mesh to the DE region occurs quite rapidly, as the fracture zone progresses almost at the blast speed. The adaptive FEM-DEM procedure is still effective in these cases as the time increment for the explicit solution is very small and the delay in introducing DEs leads to considerable savings in computing time [, | + | 4. A two-stage time integration scheme is used to solve the contact between the DE and the FE mesh. For the DE an explicit time integration scheme is used to record the impulse between <math display="inline">t</math> and <math display="inline">t + \Delta t</math> <span id='citeF-12'></span><span id='citeF-13'></span>[[#cite-12|[12]],[[#cite-13|13]]]. The impulse found is used in the FE mesh to evaluate the displacements, velocities and accelerations and also at the DE at the same time period via an implicit time integration scheme. The introduction of additional DE regions on the FE mesh evolves in time accordingly to the evolution of the stress field in the domain. For blast problems the transition of the FE mesh to the DE region occurs quite rapidly, as the fracture zone progresses almost at the blast speed. The adaptive FEM-DEM procedure is still effective in these cases as the time increment for the explicit solution is very small and the delay in introducing DEs leads to considerable savings in computing time span <span id='citeF-12'></span><span id='citeF-13'></span><span id='citeF-2'></span><span id='citeF-1'></span>[[#cite-12|[12]],[[#cite-13|13]],[[#cite-2|2]],[[#cite-1|1]]]. |

===2.2 Simulation of the explosion via a pressure function=== | ===2.2 Simulation of the explosion via a pressure function=== | ||

| − | In order to characterize the effect of the explosion within the fractured domain two different approaches have been used. The simplest one corresponds to the classical pressure-time function wide used in the literature <span id='citeF-14'></span><span id='citeF-15'></span><span id='citeF-16'></span>[[#cite-14|[14,15,16]]] which expresses the pressure as an exponential function of time where the parameters used try to reproduce the characteristic print of the more popular explosives. | + | In order to characterize the effect of the explosion within the fractured domain two different approaches have been used. The simplest one corresponds to the classical pressure-time function wide used in the literature <span id='citeF-14'></span><span id='citeF-15'></span><span id='citeF-16'></span>[[#cite-14|[14]],[[#cite-15|15]],[[#cite-16|16]]] which expresses the pressure as an exponential function of time where the parameters used try to reproduce the characteristic print of the more popular explosives. |

The amplitude and the duration of the pressure wave can be determined by the internal energy of the explosive and the size and geometry of the borehole. The following general form of a pulse function represents a large range of borehole pressures <span id='citeF-14'></span>[[#cite-14|[14]]], | The amplitude and the duration of the pressure wave can be determined by the internal energy of the explosive and the size and geometry of the borehole. The following general form of a pulse function represents a large range of borehole pressures <span id='citeF-14'></span>[[#cite-14|[14]]], | ||

| Line 59: | Line 61: | ||

|} | |} | ||

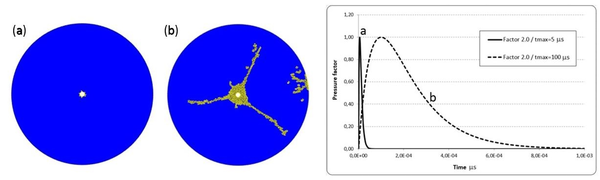

| − | where <math display="inline">P</math> is the pressure at time <math display="inline">t</math>, <math display="inline">P_0</math> is the peak pressure, and <math display="inline">\alpha </math> and <math display="inline">\beta </math> are constants. The pressure-time curves for the ratio <math display="inline">\alpha / \beta = 2</math> used in this work are depicted in Figure 2. | + | where <math display="inline">P</math> is the pressure at time <math display="inline">t</math>, <math display="inline">P_0</math> is the peak pressure, and <math display="inline">\alpha </math> and <math display="inline">\beta </math> are constants. The pressure-time curves for the ratio <math display="inline">\alpha / \beta = 2</math> used in this work are depicted in Figure [[#img-2|2]]. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-2'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig2.png|600px|Effect of pressure loading rate. (a) 20 MPa/µs loading rate. (b) 1 MPa/µs loading rate. The graphs shows the two pressure curves used]] | ||

| + | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 2:''' Effect of pressure loading rate. (a) <math>20</math> MPa/µs loading rate. (b) <math>1</math> MPa/µs loading rate. The graphs shows the two pressure curves used | ||

| + | |} | ||

===2.3 Solution of the compressible gas equations=== | ===2.3 Solution of the compressible gas equations=== | ||

| Line 71: | Line 82: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\boldsymbol {u}_{,t} + \ | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\boldsymbol {u}_{,t} + \nabla \cdot \boldsymbol {F} = 0 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (2) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (2) | ||

| Line 98: | Line 109: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Remark 1: Uppercase variables in boldface represents matrices and lowercase variables in boldface corresponds to vectors. | + | '''Remark 1''': ''Uppercase variables in boldface represents matrices and lowercase variables in boldface corresponds to vectors.'' |

where <math display="inline">{\boldsymbol u}, {\boldsymbol F}, \rho , v_i, e, p</math> denote, respectively, the vector of unknowns, the flux vector, the density, the velocity , the energy and the pressure. The Galerkin finite element discretization of the Equations [[#eq-5|5]] and [[#eq-6|6]], written in edge-based form <span id='citeF-17'></span>[[#cite-17|[17]]], yields a discrete set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) of the form: | where <math display="inline">{\boldsymbol u}, {\boldsymbol F}, \rho , v_i, e, p</math> denote, respectively, the vector of unknowns, the flux vector, the density, the velocity , the energy and the pressure. The Galerkin finite element discretization of the Equations [[#eq-5|5]] and [[#eq-6|6]], written in edge-based form <span id='citeF-17'></span>[[#cite-17|[17]]], yields a discrete set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) of the form: | ||

| Line 113: | Line 124: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | here, <math display="inline">{\boldsymbol M},\hat{u}^j, C^{ij}, {\cal F}^{ij}</math> denote the mass-matrix, the vector of nodal unknowns, the edge-coefficients for fluxes and the edge-fluxes respectively. The Galerkin edge-fluxes are replaced by numerically consistent fluxes, typically given by approximate Riemann solvers (van Leer, Roe, HLLC,...). Monotonicity is imposed either by limiting the variables before flux evaluation (van Leer, van Albada, minmod,...), or after flux evaluation via flux-corrected transport (FCT) techniques <span id='citeF-18'></span><span id='citeF-19'></span><span id='citeF-20'></span><span id='citeF-21'></span>[[#cite-18|[18,19,20,21]]]. The ODEs given by Eq. [[#eq-5|5]] are integrated in time using explicit Runge-Kutta schemes of higher order (typically 3,4), or via Taylor-Galerkin techniques. The runs shown were conducted with FEM-FCT techniques. | + | here, <math display="inline">{\boldsymbol M},\hat{u}^j, C^{ij}, {\cal F}^{ij}</math> denote the mass-matrix, the vector of nodal unknowns, the edge-coefficients for fluxes and the edge-fluxes respectively. The Galerkin edge-fluxes are replaced by numerically consistent fluxes, typically given by approximate Riemann solvers (van Leer, Roe, HLLC,...). Monotonicity is imposed either by limiting the variables before flux evaluation (van Leer, van Albada, minmod,...), or after flux evaluation via flux-corrected transport (FCT) techniques <span id='citeF-18'></span><span id='citeF-19'></span><span id='citeF-20'></span><span id='citeF-21'></span>[[#cite-18|[18]],[[#cite-19|19]],[[#cite-20|20]],[[#cite-21|21]]]. The ODEs given by Eq. [[#eq-5|5]] are integrated in time using explicit Runge-Kutta schemes of higher order (typically 3,4), or via Taylor-Galerkin techniques. The runs shown were conducted with FEM-FCT techniques. |

The pressure is obtained from various equations of state. For the gas we have used, either the ideal gas equation of state, given by | The pressure is obtained from various equations of state. For the gas we have used, either the ideal gas equation of state, given by | ||

| Line 188: | Line 199: | ||

==3 Coupled gas-solid solution via embedded mesh technique== | ==3 Coupled gas-solid solution via embedded mesh technique== | ||

| − | At each timestep, the computational solid dynamics (FEM-DEM) code transfers to the compressible gas flow solver the `wetted faces' of the (cracked) domain. The flow solver detects the edges crossed by the wetted faces and applies proper boundary conditions. A number of embedded grids for solvers of this kind have been developed over the last two decades; see <span id='citeF-24'></span><span id='citeF-25'></span><span id='citeF-26'></span><span id='citeF-4'></span><span id='citeF-27'></span><span id='citeF-28'></span><span id='citeF-29'></span><span id='citeF-30'></span><span id='citeF-31'></span>[[#cite-24|[24,25,26,4,27,28,29,30,31]]] for a detailed description. | + | At each timestep, the computational solid dynamics (FEM-DEM) code transfers to the compressible gas flow solver the `wetted faces' of the (cracked) domain. The flow solver detects the edges crossed by the wetted faces and applies proper boundary conditions. A number of embedded grids for solvers of this kind have been developed over the last two decades; see <span id='citeF-24'></span><span id='citeF-25'></span><span id='citeF-26'></span><span id='citeF-4'></span><span id='citeF-27'></span><span id='citeF-28'></span><span id='citeF-29'></span><span id='citeF-30'></span><span id='citeF-31'></span>[[#cite-24|[24]],[[#cite-25|25]],[[#cite-26|26]],[[#cite-4|4]],[[#cite-27|27]],[[#cite-28|28]],[[#cite-29|29]],[[#cite-30|30]],[[#cite-31|31]]] for a detailed description. |

==4 Examples== | ==4 Examples== | ||

| Line 196: | Line 207: | ||

===4.1 Pressure loading rate effect=== | ===4.1 Pressure loading rate effect=== | ||

| − | It is well known that the mechanical properties of rock materials are affected by the strain rate. This effect has a big influence in the rock fracture pattern. Higher strain rates produce a crushed zone and short fractures, while lower strain rates produce a small crushed zone and fewer and longer radial fractures <span id='citeF-16'></span><span id='citeF-15'></span>[[#cite-16|[16,15]]]. | + | It is well known that the mechanical properties of rock materials are affected by the strain rate. This effect has a big influence in the rock fracture pattern. Higher strain rates produce a crushed zone and short fractures, while lower strain rates produce a small crushed zone and fewer and longer radial fractures <span id='citeF-16'></span><span id='citeF-15'></span>[[#cite-16|[16]],[[#cite-15|15]]]. |

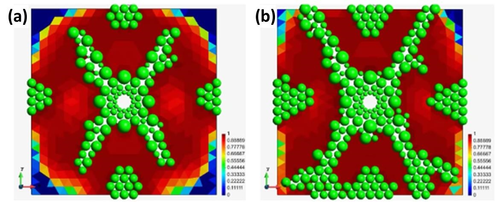

To verify these observations of the strain rate effect, two different waveforms of the blast loading have been numerically simulated with the FEM-DEM technique and compared with literature results <span id='citeF-32'></span>[[#cite-32|[32]]]. Figure [[#img-2|2]] shows the pressure–time record used for the numerical simulation. The 2D model consists of a borehole (<math display="inline">\phi = 0.005</math>m) in a circular rock mass (<math display="inline">\phi = 0.140</math>m) modeled with <math display="inline">35,046</math> elements. The material properties are E= <math display="inline">21.0</math> GPa, <math display="inline">\nu = 0.22</math>, <math display="inline">\gamma = 25,000</math>N/m<math display="inline">^3</math>, thickness = <math display="inline">0.1</math> m, <math display="inline">\sigma _t = 5.23</math> MPa and <math display="inline">G = 22</math> J/m<math display="inline">^2</math>. The pressure rising time <math display="inline">t_0</math> varies between <math display="inline">5</math> and <math display="inline">100</math> µs. The peak pressure is kept constant to <math display="inline">100</math> MPa. while the loading rates are <math display="inline">20</math> and <math display="inline">1.0</math> MPa/µs, respectively. | To verify these observations of the strain rate effect, two different waveforms of the blast loading have been numerically simulated with the FEM-DEM technique and compared with literature results <span id='citeF-32'></span>[[#cite-32|[32]]]. Figure [[#img-2|2]] shows the pressure–time record used for the numerical simulation. The 2D model consists of a borehole (<math display="inline">\phi = 0.005</math>m) in a circular rock mass (<math display="inline">\phi = 0.140</math>m) modeled with <math display="inline">35,046</math> elements. The material properties are E= <math display="inline">21.0</math> GPa, <math display="inline">\nu = 0.22</math>, <math display="inline">\gamma = 25,000</math>N/m<math display="inline">^3</math>, thickness = <math display="inline">0.1</math> m, <math display="inline">\sigma _t = 5.23</math> MPa and <math display="inline">G = 22</math> J/m<math display="inline">^2</math>. The pressure rising time <math display="inline">t_0</math> varies between <math display="inline">5</math> and <math display="inline">100</math> µs. The peak pressure is kept constant to <math display="inline">100</math> MPa. while the loading rates are <math display="inline">20</math> and <math display="inline">1.0</math> MPa/µs, respectively. | ||

| − | The simulated fracture patterns with different loading rates are compared in Figure [[#img-2|2]]. When the loading rate of the pressure is high (<math display="inline">20</math> MPa/µs), only a small crushed zone is created | + | The simulated fracture patterns with different loading rates are compared in Figure [[#img-2|2]]. When the loading rate of the pressure is high (<math display="inline">20</math> MPa/µs), only a small crushed zone is created Figure [[#img-2|2]](a). The blast energy is primarily dissipated in creating the crushed zone. When the loading rate decreases to <math display="inline">1.0</math> MPa/µs, a central crushed zone and longer radial fractures appear, as shown in Figure [[#img-2|2]](b). The results agree with those reported in <span id='citeF-15'></span><span id='citeF-16'></span><span id='citeF-32'></span>[[#cite-15|[15]],[[#cite-16|16]],[[#cite-32|32]]]. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |[[ | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

===4.2 Open air quarry analysist=== | ===4.2 Open air quarry analysist=== | ||

| Line 219: | Line 222: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

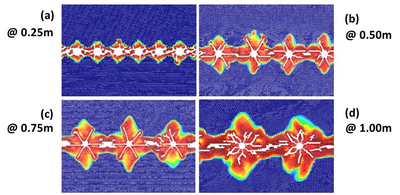

| − | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig3.png| | + | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig3.png|400px|Open air quarry analysis. Damage zone and cracks around the boreholes. Four different spacings (in meters) are shown.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="1" | '''Figure 3:''' Open air quarry analysis. Damage zone and cracks around the boreholes. Four different spacings (in meters) are shown. | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 3:''' Open air quarry analysis. Damage zone and cracks around the boreholes. Four different spacings (in meters) are shown. | ||

| Line 235: | Line 238: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

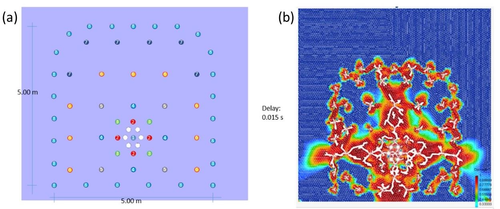

| − | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig4.png| | + | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig4.png|500px|Aguas Teñidas tunnel front. (a) Blasting sequence. (b) Crack and damage pattern.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="1" | '''Figure 4:''' Aguas Teñidas tunnel front. (a) Blasting sequence. (b) Crack and damage pattern. | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 4:''' Aguas Teñidas tunnel front. (a) Blasting sequence. (b) Crack and damage pattern. | ||

| Line 249: | Line 252: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig5.png| | + | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig5.png|500px|Damage zone and cracks on the specimen at (a) 41 µs and (b) 82 µs.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="1" | '''Figure 5:''' Damage zone and cracks on the specimen at (a) <math>41 </math> µs and (b) <math>82 </math> µs. | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 5:''' Damage zone and cracks on the specimen at (a) <math>41 </math> µs and (b) <math>82 </math> µs. | ||

| Line 259: | Line 262: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig6.png| | + | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig6.png|400px|(a) Velocity and (b) pressure distribution in the gas domain at 41 µs.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="1" | '''Figure 6:''' (a) Velocity and (b) pressure distribution in the gas domain at <math>41 </math> µs. | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 6:''' (a) Velocity and (b) pressure distribution in the gas domain at <math>41 </math> µs. | ||

| Line 267: | Line 270: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig7.png| | + | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_448339777-fig7.png|400px|(a) Velocity and (b) pressure distribution in the gas domain at 82 µs.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="1" | '''Figure 7:''' (a) Velocity and (b) pressure distribution in the gas domain at <math>82 </math> µs. | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 7:''' (a) Velocity and (b) pressure distribution in the gas domain at <math>82 </math> µs. | ||

| Line 286: | Line 289: | ||

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. | On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. | ||

| − | == | + | ==REFERENCES== |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

<div id="cite-1"></div> | <div id="cite-1"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-1|[1]]] Zárate, F. and Oñate, E. (2015) "A simple FEM-DEM technique for fracture prediction in materials and structures", Volume 2. Computational particle mechanics 3 301-314 | |

<div id="cite-2"></div> | <div id="cite-2"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-2|[2]]] Zárate, F. and Cornejo, A. and Oñate, E. (2018) "A three dimensional FEM-DEM technique for predicting the evolution of fracture in geomaterials and concrete.", Volume 3. Computational particle mechanics 5 411-420 | |

<div id="cite-3"></div> | <div id="cite-3"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-3|[3]]] Labra, C. and Rojek, J. and Oñate, E. and Zárate, F. (2008) "Advances in discrete element modelling of underground excavations", Volume 3. Acta Geotechnica 4 317-322 | |

<div id="cite-4"></div> | <div id="cite-4"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-4|[4]]] Löhner, R. (2008) "Applied CFD Techniques". J. Wiley and Sons | |

<div id="cite-5"></div> | <div id="cite-5"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-5|[5]]] Oñate, E. and Labra, C. and Zárate, F. and Rojek, J. (2012) "Modeling and simulation of the effect of the blast loading on structures using an adaptive blending of discrete and finite element methods". Taylor & Francis Group 365-372 | |

<div id="cite-6"></div> | <div id="cite-6"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-6|[6]]] Oñate, E. and Labra, C. and Zárate, F. and Rojek, J. and Miquel J. (2005) "Avances en el desarrollo de los métodos de elementos discretos y de elementos finitos para el análisis de problemas de fractura", Volume 22. Anales de Mecánica de la Fractura 27-34 | |

<div id="cite-7"></div> | <div id="cite-7"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-7|[7]]] Oñate, E. and Rojek, J. (2004) "Combination of discrete element and finite element methods for dynamic analysis of geomechanics problems", Volume 193. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 27-29 3087-3128 | |

<div id="cite-8"></div> | <div id="cite-8"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-8|[8]]] Oñate, E. and Zárate, F. and Miquel, J. and Santasusana, M. and Celigueta, M.A. and Arrufat, F. and Gandijota, R. and Valiullin, K. and Ring, L. (2015) "A local constitutive model for the discrete element method. Application to geomaterials and concrete", Volume 2. Computational Particle Mechanics 2 139-160 | |

<div id="cite-9"></div> | <div id="cite-9"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-9|[9]]] González, J.M. and Oñate, E. and Zárate, F. (2018) "Pulse fracture simulation in shale rock reservoirs. DEM and FEM-DEM approaches", Volume 3. Computational particle mechanics 5 355-373 | |

<div id="cite-10"></div> | <div id="cite-10"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-10|[10]]] Zienkiewicz, O.C and Zhu, J.Z. (1992) "The superconvergent patch recovery (SPR) and adaptive finite element refinement.", Volume 101. Comput. Methods App. Mech. Engng. 207-224 | |

<div id="cite-11"></div> | <div id="cite-11"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-11|[11]]] Cervera, M. and Chiumenti, M. and Codina, R. (2011) "Mesh objective modelling of cracks using continuous linear strain and displacements interpolations", Volume 87. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng. 962-987 | |

<div id="cite-12"></div> | <div id="cite-12"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-12|[12]]] Oñate, E. and Labra, C. and Zárate, F. and Rojek, J. (2012) "Modelling and simulation of the effect of blast loading on structures using an adaptive blending of discrete and finite element methods". Risk Analysis, Dam Safety, Dam Security and Critical Infrastructure Management. ISBN 978-0-415-62078-9 | |

<div id="cite-13"></div> | <div id="cite-13"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-13|[13]]] Rojek, J. and Oñate, E. (2007) "Multiscale analysis using a coupled discrete/finite element model. Interact", Volume 1. Interaction and Multiscale Mech. 1 1-31 | |

<div id="cite-14"></div> | <div id="cite-14"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-14|[14]]] Cho, Sh. and Kaneko K. (2004) "Influence of the applied pressure waveform on the dynamic fracture processes in rock", Volume 41. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 5 771-784 | |

<div id="cite-15"></div> | <div id="cite-15"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-15|[15]]] Cho, Sh. and Ogata, Y. and Kaneko, K. (2003) "Strain rate dependency of the dynamic tensile strength of rock", Volume 40. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 5 763-777 | |

<div id="cite-16"></div> | <div id="cite-16"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-16|[16]]] Donzé, F.V. and Bouchez, J. and Magnier S.A. (1997) "Modeling fractures in rock blasting", Volume 34. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 8 1153-1163 | |

<div id="cite-17"></div> | <div id="cite-17"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-17|[17]]] H. Luo, H. and Baum, J.D. and Löhner, R. (1994) "Edge-Based Finite Element Scheme for the Euler Equations", Volume 32. AIAA J. 6 1183-1190 | |

<div id="cite-18"></div> | <div id="cite-18"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-18|[18]]] Boris, J.P. and Book, D.L. (1973) "Flux-corrected transport. I. SHASTA, a fluid transport algorithm that works", Volume 11. Journal of Computational Physics 1 38-69 | |

<div id="cite-19"></div> | <div id="cite-19"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-19|[19]]] Kuzmin, D. and Löhner, R. and Turek, S. (2012) "Flux-Corrected Transport, Principles, Algorithms and Applications". Springer | |

<div id="cite-20"></div> | <div id="cite-20"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-20|[20]]] Rainald Löhner, R. and Morgan, K. and Peraire, J. and Vahdati, M. (1987) "Finite element flux-corrected transport (FEM-FCT) for the euler and Navier-Stokes equations", Volume 7. Int. J. Num. Meth. Fluids 10 1093-1109 | |

<div id="cite-21"></div> | <div id="cite-21"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-21|[21]]] Zalesak, S.T. (1979) "Fully multidimensional flux-corrected transport algorithms for fluids", Volume 31. Journal of Computational Physics 3 335-362 | |

<div id="cite-22"></div> | <div id="cite-22"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-22|[22]]] Kury, J.W. and Lee, E.L. and Hornig, H.C. and McDonnel, J.L. and Ornellas, D.L. and Finger, M. and Strange, F.M. and Wilkins, M. L. (1965) "Metal Acceleration by Chemical Explosives". Proceedings of the 4th Fourth Detonation Symposium 3-13 | |

<div id="cite-23"></div> | <div id="cite-23"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-23|[23]]] Lee, E.L. and Hornig, H.C. and Kury, J.W. (1968) "Adiabatic Expansion of High Explosive Detonation Products". LLNL, UCRL-50422 | |

<div id="cite-24"></div> | <div id="cite-24"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-24|[24]]] Aftosmis, M.J. and Berger, M.J. and Adomavicius, G. (2000) "A Parallel Multilevel Method for Adaptively Refined Cartesian Grids with Embedded Boundaries", Volume. AIAA-00-0808 | |

<div id="cite-25"></div> | <div id="cite-25"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-25|[25]]] Dadone, A. and Grossman, B. (2002) "An Immersed Boundary Methodology for Inviscid Flows on Cartesian Grids", Volume. AIAA-02-1059 | |

<div id="cite-26"></div> | <div id="cite-26"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-26|[26]]] Landsberg, A.M. and Boris, J.P. (1997) "The Virtual Cell Embedding Method: A Simple Approach for Gridding Complex Geometries", Volume. AIAA-97-1982 | |

<div id="cite-27"></div> | <div id="cite-27"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-27|[27]]] Löhner, R. and Baum, J.D. and Mestreau, E. and Sharov, D. and Charman, C. and Pelessone, D. (2004) "Adaptive embedded unstructured grid methods", Volume 60. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng. 3 641-660 | |

<div id="cite-28"></div> | <div id="cite-28"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-28|[28]]] Löhner, R. and Baum, J.D. and Mestreau, E.L. and Rice, D. (2007) "Comparison of Body-Fitted, Embedded and Immersed 3-D Euler Predictions for Blast Loads on Columns", Volume. AIAA-07-1133 | |

<div id="cite-29"></div> | <div id="cite-29"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-29|[29]]] Melton, J. and Berger, M. and Aftosmis, M. (1993) "3D applications of a Cartesian grid Euler method", Volume. AIAA-93-0853-CP | |

<div id="cite-30"></div> | <div id="cite-30"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-30|[30]]] Mittal, R. and Iaccarino, G. (2005) "Immersed Boundary Methods", Volume 37. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 239-261 | |

<div id="cite-31"></div> | <div id="cite-31"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-31|[31]]] Pember, R.B. and Bell, J.B. and Colella, P. and Crutchfield, W.Y. and Welcome, M.L. (1995) "An Adaptive Cartesian Grid Method for Unsteady Compressible Flow in Irregular Regions", Volume 120. Journal of Computational Physics 2 278-304 | |

<div id="cite-32"></div> | <div id="cite-32"></div> | ||

| − | + | [[#citeF-32|[32]]] Ma, G.W. and An, X.M. (2008) "Numerical simulation of blasting-induced rock fractures", Volume 45. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 6 966-975 | |

Latest revision as of 10:39, 28 October 2019

Published in Underground Space, Vol. 3 (4), pp. 310-316, 2018

doi: 10.1016/j.undsp.2018.09.002

Abstract

We present recent developments in the coupling of the finite element method (FEM) and the discrete element method (DEM) for analysis of rock blasting operations in tunnels. The coupled FEM-DEM technique has proven to be an efficient procedure for predicting the multi-fracture of rock induced by the loads generated in blasting situations.

The coupled FEM-DEM procedure is applied in the tunnel construction, as well as to gas pressure blasting pyrotechnics situations to break rock for excavation of the tunnel front. In the latter case the effect of gas explosion is modelled by solving with the FEM the equations of gas dynamics in the analysis domain. The effect of the gas forces in the underlying rock mass is modelled via an embedded fluid-structure interaction method.

The efficiency of the coupled FEM-DEM technique is demonstrated in several examples of fracture tests and rock blasting problems related to tunnel engineering. The examples presented show that the combination of the DEM with simple 3-noded linear triangular elements (for 2D problems) correctly captures the onset of fractures and their evolution accounting for the penetration of the gas in the failure domain [1,2].

Keywords: Discrete elements, finite elements, fracture mechanics, FEM-DEM, gas dynamics.

1 Introduction

In this work we extend the simple FEM-DEM procedure presented in [2,1], for analyzing of blasting operation in tunnel fronts leads to multiple fractures and material disgregation of the rock model.

The computed prediction of fractures in a rock induced by a blast load using the finite element method (FEM) poses numerous challenges due to the difficulty of the FEM for computing the onset and propagation of multiple cracks. The problem complexity increases if the effect of the gas pressure acting within the cracks is taken into account [3,4,5].

The FEM-DEM procedure is based on an initial discretization of the analysis domain by a mesh of standard finite elements (FE). Onset of fracture at a point is governed by a simple damage model. Once a crack is detected at an element side in the FE mesh, discrete elements (DE) are generated at the nodes sharing the side. A DEM approach is used to model the evolution of the crack in the fractured solid [3,5,6,7,8]. This optimizes the use of DE to zones where they can be more effective, which considerably simplifies the contact search process and reduces the overall computational cost. Applications of the FEM-DEM technique can be found in [9,2,1].

In this paper we use two methods to simulate the pressure-time behavior of an explosion: a) The direct application of the well known pulse function on the fracture faces, and b) Solution of the gas dynamic equations within the fracture domain coupled to the solid mechanics solution using an embedded mesh approach. Examples of boths numerical procedures to rock blasting solutions are given.

2 Basics of the Implementation

2.1 FEM DEM approach

We solve the solid domain using an implicit solution in time of the dynamic equilibrium equations. In essence, the adaptive FEM-DEM procedure starts with a discretization of the analysis domain using a FE mesh only and operates as explained next.

1. At each time instant the stress level is verified at each element. For linear triangles and tetrahedra implies computing the strains and stresses at the middle point of the element sides. This strategy follows the idea of the superconvergent patch recovery procedure [10] and provides a better stress field than the one obtained at the gauss points [11].

2. The threshold of failure (fracture) of each element is evaluated. This can be done via procedures based on the point-wise value of the stresses (or the strains), or using an adequate energy norm. In our work the rock has a linear elastic behavior limited by a simple Rankine crack model with a linear damage rule which has been used to define the onset of fracture at the mid-point of the element sides [11]. The element damage corresponds to the largest value of the damage parameter at the different cut planes existing in a triangle. The cut plane damage is evaluated as the mean value of the damage parameter at the edges involved in such cut plane as shown in Figure 1(a), were two element sides are damaged.

3. A collection of DE is introduced within the FE that have exceeded the failure threshold. In our work this occurs when element damage reaches a 95% of the threshold value. At this moment, the continuum region previously occupied by the damaged element is modelled with a collection of DE created at the element nodes and the damaged elements are removed Figure 1(b). The radius of the new DE is defined as the maximum possible to avoid collisions with other DE. The mass of the system remains constant because 1/3 of the element mass goes to each DE created at the element nodes.

|

| Figure 1: (a) Two element sides damaged in a FE mesh. (b) Element removal and DE creation (not in scale) at an element with two sides exceeds the damage threshold. |

4. A two-stage time integration scheme is used to solve the contact between the DE and the FE mesh. For the DE an explicit time integration scheme is used to record the impulse between and [12,13]. The impulse found is used in the FE mesh to evaluate the displacements, velocities and accelerations and also at the DE at the same time period via an implicit time integration scheme. The introduction of additional DE regions on the FE mesh evolves in time accordingly to the evolution of the stress field in the domain. For blast problems the transition of the FE mesh to the DE region occurs quite rapidly, as the fracture zone progresses almost at the blast speed. The adaptive FEM-DEM procedure is still effective in these cases as the time increment for the explicit solution is very small and the delay in introducing DEs leads to considerable savings in computing time span [12,13,2,1].

2.2 Simulation of the explosion via a pressure function

In order to characterize the effect of the explosion within the fractured domain two different approaches have been used. The simplest one corresponds to the classical pressure-time function wide used in the literature [14,15,16] which expresses the pressure as an exponential function of time where the parameters used try to reproduce the characteristic print of the more popular explosives.

The amplitude and the duration of the pressure wave can be determined by the internal energy of the explosive and the size and geometry of the borehole. The following general form of a pulse function represents a large range of borehole pressures [14],

|

|

(1) |

where is the pressure at time , is the peak pressure, and and are constants. The pressure-time curves for the ratio used in this work are depicted in Figure 2.

|

| Figure 2: Effect of pressure loading rate. (a) MPa/µs loading rate. (b) MPa/µs loading rate. The graphs shows the two pressure curves used |

2.3 Solution of the compressible gas equations

The effect of the (compressible) gas within the fractures is modeled by solving the Euler equations, given by

|

|

(2) |

|

|

(3) |

|

|

(4) |

Remark 1: Uppercase variables in boldface represents matrices and lowercase variables in boldface corresponds to vectors.

where denote, respectively, the vector of unknowns, the flux vector, the density, the velocity , the energy and the pressure. The Galerkin finite element discretization of the Equations 5 and 6, written in edge-based form [17], yields a discrete set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) of the form:

|

|

(5) |

here, denote the mass-matrix, the vector of nodal unknowns, the edge-coefficients for fluxes and the edge-fluxes respectively. The Galerkin edge-fluxes are replaced by numerically consistent fluxes, typically given by approximate Riemann solvers (van Leer, Roe, HLLC,...). Monotonicity is imposed either by limiting the variables before flux evaluation (van Leer, van Albada, minmod,...), or after flux evaluation via flux-corrected transport (FCT) techniques [18,19,20,21]. The ODEs given by Eq. 5 are integrated in time using explicit Runge-Kutta schemes of higher order (typically 3,4), or via Taylor-Galerkin techniques. The runs shown were conducted with FEM-FCT techniques.

The pressure is obtained from various equations of state. For the gas we have used, either the ideal gas equation of state, given by

|

|

(6) |

or a table look-up , which may also be interpreted as a non-constant .

The high explosive material (HEM) is modeled with the Jones-Wilkins-Lee (JWL) equation of state [22,23], given by:

|

|

(7) |

where denotes the relative volume of the gas:

|

|

(8) |

note that the equivalent ideal gas value of is given by . However, for many materials is quite far from . Therefore, a combination of EOS is employed once the density of the HEM falls below a threshold or switch value.

Afterburning is modelled by adding energy via a burn coefficient that is obtained from

|

|

(9) |

after updating , the energy added is given by:

|

|

(10) |

where is the afterburn energy.

3 Coupled gas-solid solution via embedded mesh technique

At each timestep, the computational solid dynamics (FEM-DEM) code transfers to the compressible gas flow solver the `wetted faces' of the (cracked) domain. The flow solver detects the edges crossed by the wetted faces and applies proper boundary conditions. A number of embedded grids for solvers of this kind have been developed over the last two decades; see [24,25,26,4,27,28,29,30,31] for a detailed description.

4 Examples

Many examples in 2D and 3D have been performed in order to verify the accuracy and robustness of the FEM-DEM formulation for analysis of multifractures in solids, all of them with excellent results [2,1]. Herein some examples related to rock blasting problems are present in order to show the usefulness of the FEM-DEM procedure in this field.

4.1 Pressure loading rate effect

It is well known that the mechanical properties of rock materials are affected by the strain rate. This effect has a big influence in the rock fracture pattern. Higher strain rates produce a crushed zone and short fractures, while lower strain rates produce a small crushed zone and fewer and longer radial fractures [16,15].

To verify these observations of the strain rate effect, two different waveforms of the blast loading have been numerically simulated with the FEM-DEM technique and compared with literature results [32]. Figure 2 shows the pressure–time record used for the numerical simulation. The 2D model consists of a borehole (m) in a circular rock mass (m) modeled with elements. The material properties are E= GPa, , N/m, thickness = m, MPa and J/m. The pressure rising time varies between and µs. The peak pressure is kept constant to MPa. while the loading rates are and MPa/µs, respectively.

The simulated fracture patterns with different loading rates are compared in Figure 2. When the loading rate of the pressure is high ( MPa/µs), only a small crushed zone is created Figure 2(a). The blast energy is primarily dissipated in creating the crushed zone. When the loading rate decreases to MPa/µs, a central crushed zone and longer radial fractures appear, as shown in Figure 2(b). The results agree with those reported in [15,16,32].

4.2 Open air quarry analysist

The geometry analyzed corresponds to a m 2D domain constrained at all its edges except the lower one. The cutting line was set at m from the free side. Different spacings of the boreholes ( m) were analyzed (, , and m). The load pressure is defined as in curve (b) of Figure 2. The material properties are GPa, , N/m, thick = m, MPa and J/m.

The results obtained show a clear correlation () of the width of the damaged zone respect the borehole spacing, which goes from m for the m spacing up to m for m spacing, as shown in Figure 3. This results are the expected ones and confirm the good prediction capabilities of the FEM-DEM simulation.

|

| Figure 3: Open air quarry analysis. Damage zone and cracks around the boreholes. Four different spacings (in meters) are shown. |

4.3 “Aguas Teñidas” tunnel front

“Aguas Teñidas” is a mine located in the province of Huelva, Spain. It is a conformant sulfide deposit of the Iberian Pyrite Belt. This mine produces copper and polymetallic. The exploitation is carried out using mainly conventional drilling equipment for blasting.

A front blasting sequence is analyzed with the pressure rising time of µs. and a peak pressure of MPa. The material properties correspond to GPa, , MPa and J/m.

The tunnel front has boreholes classified in blasting groups as shown in Figure 4(a). The blasting delay is µs between each group. No initial pressure is applied at the rock mass; This means that the tunnel is assumed to be at a very low depth. On Figure 4(b) the damage at the final time of analysis is presented. It is remarkable the sub-excavation at the base of the tunnel which matches the real problem. The horizontal damage zone is due to the zero initial pressure in the rock mass.

|

| Figure 4: Aguas Teñidas tunnel front. (a) Blasting sequence. (b) Crack and damage pattern. |

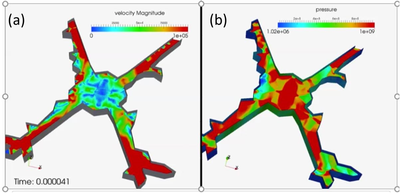

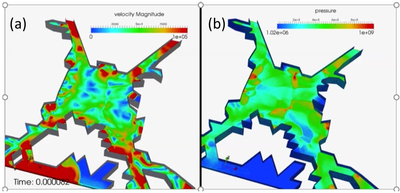

4.4 Coupled blast-crack problem

A simple example is shown for the coupled solution between the cracking in a square solid rock mass and the CFD analysis in which the explosive state equations are solved coupled to the FEM-DEM solution. The example corresponds to a 2D granite rock sample of m and a borehole of m. The explosive used corresponds to a C4 kind. Besides the simplicity of the example, it proves the usefulness of the coupling blast-cracking scheme proposed.

In Figure 5 the cracks and damage zone for two different times ( µs and µs) are presented. The cracked domain is passed to the CFD solver each time step in order to compute the pressure evolution in the gas zone which value is returned to the FEM-DEM solver for the solid mechanical analysis.

|

| Figure 5: Damage zone and cracks on the specimen at (a) µs and (b) µs. |

Figures 6 and 7 shown the CFD results for the same times. Figures (a) display the fluid velocity and Figures (b) the pressure evolution in the gas zone within the cracks. We highlight the shockwaves produced by the explosion within the gas domain.

|

| Figure 6: (a) Velocity and (b) pressure distribution in the gas domain at µs. |

|

| Figure 7: (a) Velocity and (b) pressure distribution in the gas domain at µs. |

5 Conclusions

A simple FEM-DEM methodology has been presented for reproducing the cracking pattern in rock blasting problems. The good results obtained indicate that the FEM-DEM technique is an efficient and promising procedure for solving rock excavation and blasting situations in tunnels.

In addition to the standard pressure-time functions, the effect of the gas forces whitin the fractures in the underlying rock mass has been modelled with an embedded fluid-structure interaction method. This couppled procedure accurately predicts the progressive multi-fracture of the rock accounting for the penetration of the gas in the fractured domain modelled with the FEM-DEM procedure described

6 Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Tuñel project funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. (2015-2019) via the subprogram CIEN (IDI-20150705) and also the support of the EZUANA project (BIA2016-78544-R), funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science of Spain.

7 Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

[1] Zárate, F. and Oñate, E. (2015) "A simple FEM-DEM technique for fracture prediction in materials and structures", Volume 2. Computational particle mechanics 3 301-314

[2] Zárate, F. and Cornejo, A. and Oñate, E. (2018) "A three dimensional FEM-DEM technique for predicting the evolution of fracture in geomaterials and concrete.", Volume 3. Computational particle mechanics 5 411-420

[3] Labra, C. and Rojek, J. and Oñate, E. and Zárate, F. (2008) "Advances in discrete element modelling of underground excavations", Volume 3. Acta Geotechnica 4 317-322

[4] Löhner, R. (2008) "Applied CFD Techniques". J. Wiley and Sons

[5] Oñate, E. and Labra, C. and Zárate, F. and Rojek, J. (2012) "Modeling and simulation of the effect of the blast loading on structures using an adaptive blending of discrete and finite element methods". Taylor & Francis Group 365-372

[6] Oñate, E. and Labra, C. and Zárate, F. and Rojek, J. and Miquel J. (2005) "Avances en el desarrollo de los métodos de elementos discretos y de elementos finitos para el análisis de problemas de fractura", Volume 22. Anales de Mecánica de la Fractura 27-34

[7] Oñate, E. and Rojek, J. (2004) "Combination of discrete element and finite element methods for dynamic analysis of geomechanics problems", Volume 193. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 27-29 3087-3128

[8] Oñate, E. and Zárate, F. and Miquel, J. and Santasusana, M. and Celigueta, M.A. and Arrufat, F. and Gandijota, R. and Valiullin, K. and Ring, L. (2015) "A local constitutive model for the discrete element method. Application to geomaterials and concrete", Volume 2. Computational Particle Mechanics 2 139-160

[9] González, J.M. and Oñate, E. and Zárate, F. (2018) "Pulse fracture simulation in shale rock reservoirs. DEM and FEM-DEM approaches", Volume 3. Computational particle mechanics 5 355-373

[10] Zienkiewicz, O.C and Zhu, J.Z. (1992) "The superconvergent patch recovery (SPR) and adaptive finite element refinement.", Volume 101. Comput. Methods App. Mech. Engng. 207-224

[11] Cervera, M. and Chiumenti, M. and Codina, R. (2011) "Mesh objective modelling of cracks using continuous linear strain and displacements interpolations", Volume 87. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng. 962-987

[12] Oñate, E. and Labra, C. and Zárate, F. and Rojek, J. (2012) "Modelling and simulation of the effect of blast loading on structures using an adaptive blending of discrete and finite element methods". Risk Analysis, Dam Safety, Dam Security and Critical Infrastructure Management. ISBN 978-0-415-62078-9

[13] Rojek, J. and Oñate, E. (2007) "Multiscale analysis using a coupled discrete/finite element model. Interact", Volume 1. Interaction and Multiscale Mech. 1 1-31

[14] Cho, Sh. and Kaneko K. (2004) "Influence of the applied pressure waveform on the dynamic fracture processes in rock", Volume 41. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 5 771-784

[15] Cho, Sh. and Ogata, Y. and Kaneko, K. (2003) "Strain rate dependency of the dynamic tensile strength of rock", Volume 40. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 5 763-777

[16] Donzé, F.V. and Bouchez, J. and Magnier S.A. (1997) "Modeling fractures in rock blasting", Volume 34. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 8 1153-1163

[17] H. Luo, H. and Baum, J.D. and Löhner, R. (1994) "Edge-Based Finite Element Scheme for the Euler Equations", Volume 32. AIAA J. 6 1183-1190

[18] Boris, J.P. and Book, D.L. (1973) "Flux-corrected transport. I. SHASTA, a fluid transport algorithm that works", Volume 11. Journal of Computational Physics 1 38-69

[19] Kuzmin, D. and Löhner, R. and Turek, S. (2012) "Flux-Corrected Transport, Principles, Algorithms and Applications". Springer

[20] Rainald Löhner, R. and Morgan, K. and Peraire, J. and Vahdati, M. (1987) "Finite element flux-corrected transport (FEM-FCT) for the euler and Navier-Stokes equations", Volume 7. Int. J. Num. Meth. Fluids 10 1093-1109

[21] Zalesak, S.T. (1979) "Fully multidimensional flux-corrected transport algorithms for fluids", Volume 31. Journal of Computational Physics 3 335-362

[22] Kury, J.W. and Lee, E.L. and Hornig, H.C. and McDonnel, J.L. and Ornellas, D.L. and Finger, M. and Strange, F.M. and Wilkins, M. L. (1965) "Metal Acceleration by Chemical Explosives". Proceedings of the 4th Fourth Detonation Symposium 3-13

[23] Lee, E.L. and Hornig, H.C. and Kury, J.W. (1968) "Adiabatic Expansion of High Explosive Detonation Products". LLNL, UCRL-50422

[24] Aftosmis, M.J. and Berger, M.J. and Adomavicius, G. (2000) "A Parallel Multilevel Method for Adaptively Refined Cartesian Grids with Embedded Boundaries", Volume. AIAA-00-0808

[25] Dadone, A. and Grossman, B. (2002) "An Immersed Boundary Methodology for Inviscid Flows on Cartesian Grids", Volume. AIAA-02-1059

[26] Landsberg, A.M. and Boris, J.P. (1997) "The Virtual Cell Embedding Method: A Simple Approach for Gridding Complex Geometries", Volume. AIAA-97-1982

[27] Löhner, R. and Baum, J.D. and Mestreau, E. and Sharov, D. and Charman, C. and Pelessone, D. (2004) "Adaptive embedded unstructured grid methods", Volume 60. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng. 3 641-660

[28] Löhner, R. and Baum, J.D. and Mestreau, E.L. and Rice, D. (2007) "Comparison of Body-Fitted, Embedded and Immersed 3-D Euler Predictions for Blast Loads on Columns", Volume. AIAA-07-1133

[29] Melton, J. and Berger, M. and Aftosmis, M. (1993) "3D applications of a Cartesian grid Euler method", Volume. AIAA-93-0853-CP

[30] Mittal, R. and Iaccarino, G. (2005) "Immersed Boundary Methods", Volume 37. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 239-261

[31] Pember, R.B. and Bell, J.B. and Colella, P. and Crutchfield, W.Y. and Welcome, M.L. (1995) "An Adaptive Cartesian Grid Method for Unsteady Compressible Flow in Irregular Regions", Volume 120. Journal of Computational Physics 2 278-304

[32] Ma, G.W. and An, X.M. (2008) "Numerical simulation of blasting-induced rock fractures", Volume 45. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 6 966-975

Document information

Published on 01/01/2018

DOI: 10.1016/j.undsp.2018.09.002

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?