m (Move page script moved page Draft Samper 860628002 to Onate et al 2004g) |

|||

| (87 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Most of these problems disappear if a ''Lagrangian description'' is used to formulate the governing equations of both the solid and the fluid domain. In the Lagrangian formulation the motion of the individual particles are followed and, consequently, nodes in a finite element mesh can be viewed as moving “particles”. Hence, the motion of the mesh discretizing the total domain (including both the fluid and solid parts) is followed during the transient solution. | Most of these problems disappear if a ''Lagrangian description'' is used to formulate the governing equations of both the solid and the fluid domain. In the Lagrangian formulation the motion of the individual particles are followed and, consequently, nodes in a finite element mesh can be viewed as moving “particles”. Hence, the motion of the mesh discretizing the total domain (including both the fluid and solid parts) is followed during the transient solution. | ||

| − | In this paper we present an overview of a particular class of Lagrangian formulation developed by the authors to solve problems involving the interaction between fluids and solids in a unified manner. The method, called the ''particle finite element method'' (PFEM), treats the mesh nodes in the fluid and solid domains as particles which can freely move and even separate from the main fluid domain representing, for instance, the effect of water drops. A finite element mesh connects the nodes defining the discretized domain where the governing equations are solved in the standard FEM fashion. The PFEM is the natural evolution of recent work of the authors for the solution of FSI problems using Lagrangian finite element and meshless methods [Aubry ''et al.'' (2004) <span id="citeF-1"></span>[[#cite-1|[1]]]; Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003b; 2004) <span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]],<span id="citeF-21"></span>[[#cite-21|21]],<span id="citeF-23"></span>[[#cite-23|23]]]; Oñate ''et al.'' (2003; 2004)<span id="citeF-33"></span>[[#cite-33|[33]],<span id="citeF-34"></span>[[#cite-34|34]]]]. | + | In this paper we present an overview of a particular class of Lagrangian formulation developed by the authors to solve problems involving the interaction between fluids and solids in a unified manner. The method, called the ''particle finite element method'' (PFEM), treats the mesh nodes in the fluid and solid domains as particles which can freely move and even separate from the main fluid domain representing, for instance, the effect of water drops. A finite element mesh connects the nodes defining the discretized domain where the governing equations are solved in the standard FEM fashion. The PFEM is the natural evolution of recent work of the authors for the solution of FSI problems using Lagrangian finite element and meshless methods [Aubry ''et al.'' (2004) <span id="citeF-1"></span>[[#cite-1|[1]]]; Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003b; 2004) <span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]],<span id="citeF-21"></span>[[#cite-21|21]],<span id="citeF-23"></span>[[#cite-23|23]]]; Oñate ''et al.'' (2003; 2004) <span id="citeF-33"></span>[[#cite-33|[33]],<span id="citeF-34"></span>[[#cite-34|34]]]]. |

| − | An obvious advantage of the Lagrangian formulation is that the convective terms disappear from the fluid equations. The difficulty is however transferred to the problem of adequately (and efficiently) moving the mesh nodes. Indeed for large mesh motions remeshing may be a frequent necessity along the time solution. We use an innovative mesh regeneration procedure blending elements of different shapes using an extended Delaunay tesselation [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003c)<span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]],<span id="citeF-22"></span>[[#cite-22|22]]]. Furthermore, this special polyhedral finite element needs special shape funtions. In this paper, meshless finite element (MFEM) shape functions have been used [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a)<span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]]]]. | + | An obvious advantage of the Lagrangian formulation is that the convective terms disappear from the fluid equations. The difficulty is however transferred to the problem of adequately (and efficiently) moving the mesh nodes. Indeed for large mesh motions remeshing may be a frequent necessity along the time solution. We use an innovative mesh regeneration procedure blending elements of different shapes using an extended Delaunay tesselation [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003c) <span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]],<span id="citeF-22"></span>[[#cite-22|22]]]. Furthermore, this special polyhedral finite element needs special shape funtions. In this paper, meshless finite element (MFEM) shape functions have been used [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a) <span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]]]]. |

| − | The need to properly treat the incompressibility condition in the fluid still remains in the Lagrangian formulation. The use of standard finite element interpolations may lead to a volumetric locking defect unless some precautions are taken. A number of stabilization finite element procedures aiming to alleviate the locking problem in incompressible fluids have been proposed and some of them are listed in [Chorin (1967)<span id="citeF-2"></span>[[#cite-2|[2]]]; Codina (2002)<span id="citeF-3"></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]]; Codina ''et al.'' (1998)<span id="citeF-4"></span>[[#cite-4|[4]]]; Codina and Blasco (2000)<span id="citeF-5"></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]]; Codina and Zienkiewicz (2002)<span id="citeF-6"></span>[[#cite-6|[6]]]; Cruchaga and Oñate (1997; 1999)<span id="citeF-7"></span>[[#cite-7|[7]],<span id="citeF-8"></span>[[#cite-8|8]]]; Donea and Huerta (2003)<span id="citeF-9"></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]]; Franca and Frey (1992)<span id="citeF-11"></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]]; Hansbo and Szepessy (1990)<span id="citeF- | + | The need to properly treat the incompressibility condition in the fluid still remains in the Lagrangian formulation. The use of standard finite element interpolations may lead to a volumetric locking defect unless some precautions are taken. A number of stabilization finite element procedures aiming to alleviate the locking problem in incompressible fluids have been proposed and some of them are listed in [Chorin (1967) <span id="citeF-2"></span>[[#cite-2|[2]]]; Codina (2002) <span id="citeF-3"></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]]; Codina ''et al.'' (1998) <span id="citeF-4"></span>[[#cite-4|[4]]]; Codina and Blasco (2000) <span id="citeF-5"></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]]; Codina and Zienkiewicz (2002) <span id="citeF-6"></span>[[#cite-6|[6]]]; Cruchaga and Oñate (1997; 1999) <span id="citeF-7"></span>[[#cite-7|[7]],<span id="citeF-8"></span>[[#cite-8|8]]]; Donea and Huerta (2003) <span id="citeF-9"></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]]; Franca and Frey (1992) <span id="citeF-11"></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]]; Hansbo and Szepessy (1990) <span id="citeF-15"></span>[[#cite-15|[15]]]; Hughes ''et al.'' (1986; 1989; 1994) <span id="citeF-16"></span>[[#cite-16|[16]],<span id="citeF-17"></span>[[#cite-17|17]],<span id="citeF-18"></span>[[#cite-18|18]]]; Oñate (1998) <span id="citeF-27"></span>[[#cite-27|[27]]]; Sheng ''et al.'' (1996) <span id="citeF-36"></span>[[#cite-36|[36]]]; Tezduyar ''et al.'' (1992) <span id="citeF-41"></span>[[#cite-41|[41]]]; Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000) <span id="citeF-43"></span>[[#cite-43|[43]]]; Storti ''et al.'' (2004) <span id="citeF-37"></span>[[#cite-37|[37]]]]. A general aim is to use low order elements with equal order interpolation for the velocity and pressure variables. In our work the stabilization via a finite calculus (FIC) procedure has been chosen [Oñate (2000) <span id="citeF-28"></span>[[#cite-28|[28]]]]. Recent applications of the FIC method for incompressible flow analysis using linear triangles and tetrahedra are reported in [García and Oñate (2003) <span id="citeF-12"></span>[[#cite-12|[12]]]; Oñate (2004) <span id="citeF-29"></span>[[#cite-29|[29]]]; Oñate ''et al.'' (2000; 2004) <span id="citeF-31"></span>[[#cite-31|[31]],<span id="citeF-34"></span>[[#cite-34|34]]]; Oñate and García (2001) <span id="citeF-32"></span>[[#cite-32|[32]]]; Oñate and Idelsohn (1998) <span id="citeF-30"></span>[[#cite-30|[30]]]]. |

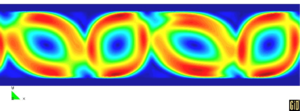

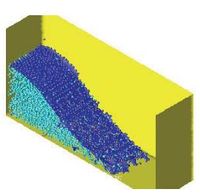

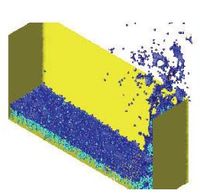

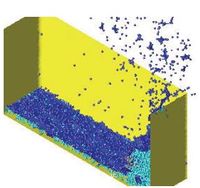

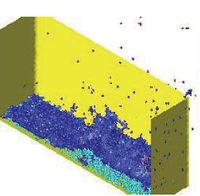

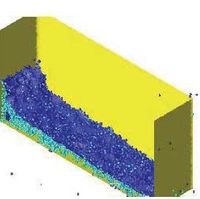

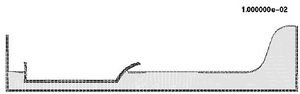

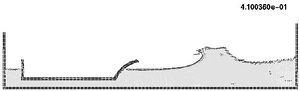

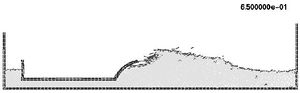

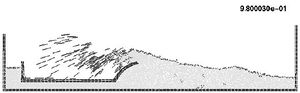

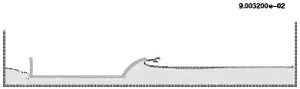

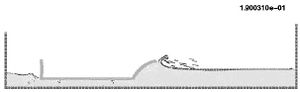

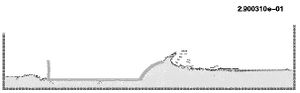

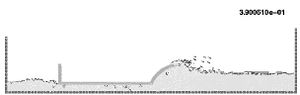

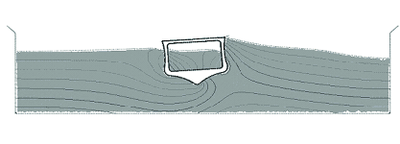

| − | The Lagrangian formulation has many advantages for tracking the motion of fluid particles in flows accounting for large displacements of the fluid surface as in the case of breaking waves and splashing of liquids (Figure [[#img-1|1]]). We note that the information in the PFEM is typically nodal-based, i.e. the element mesh is mainly used to obtain the values of the state variables (i.e. velocities, pressure, etc.) at the nodes. A difficulty arises in the identification of the boundary of the domain from a given collection of nodes. Indeed the “boundary” can include the free surface in the fluid and the individual particles moving outside the fluid domain. In our work the Alpha Shape technique [Edelsbrunner and Mucke (1999)<span id="citeF-10"></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]]] is used to identify the boundary nodes. | + | The Lagrangian formulation has many advantages for tracking the motion of fluid particles in flows accounting for large displacements of the fluid surface as in the case of breaking waves and splashing of liquids (Figure [[#img-1|1]]). We note that the information in the PFEM is typically nodal-based, i.e. the element mesh is mainly used to obtain the values of the state variables (i.e. velocities, pressure, etc.) at the nodes. A difficulty arises in the identification of the boundary of the domain from a given collection of nodes. Indeed the “boundary” can include the free surface in the fluid and the individual particles moving outside the fluid domain. In our work the Alpha Shape technique [Edelsbrunner and Mucke (1999) <span id="citeF-10"></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]]] is used to identify the boundary nodes. |

<div id='img-1'></div> | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

Let us consider a domain containing both fluid and solid subdomains. The moving fluid particles interact with the solid boundaries thereby inducing the deformation of the solid which in turn affects the flow motion and, therefore, the problem is fully coupled. | Let us consider a domain containing both fluid and solid subdomains. The moving fluid particles interact with the solid boundaries thereby inducing the deformation of the solid which in turn affects the flow motion and, therefore, the problem is fully coupled. | ||

| − | FSI problems traditionally have been solved using an arbitrary Eulerian-Lagrangian description (ALE) for the flow equation whereas the structure is modelled with a full Lagrangian formulation. Many examples of applications of this type of approach are found in the literature. A good review can be found in [Donea and Huerta (2003)<span id="citeF-9"></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]]; Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000)<span id="citeF-43"></span>[[#cite-43|[43]]]]. | + | FSI problems traditionally have been solved using an arbitrary Eulerian-Lagrangian description (ALE) for the flow equation whereas the structure is modelled with a full Lagrangian formulation. Many examples of applications of this type of approach are found in the literature. A good review can be found in [Donea and Huerta (2003) <span id="citeF-9"></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]]; Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000) <span id="citeF-43"></span>[[#cite-43|[43]]]]. |

In the PFEM approach presented here, both the fluid and the solid domains are modelled using an ''updated'' ''Lagrangian formulation''. The finite element method (FEM) is used to solve the continuum equations in both domains. Hence a mesh discretizing these domains must be generated in order to solve the governing equations for both the fluid and solid problems in the standard FEM fashion. We note once more that the nodes discretizing the fluid and solid domains can be viewed as material particles which motion is tracked during the transient solution. | In the PFEM approach presented here, both the fluid and the solid domains are modelled using an ''updated'' ''Lagrangian formulation''. The finite element method (FEM) is used to solve the continuum equations in both domains. Hence a mesh discretizing these domains must be generated in order to solve the governing equations for both the fluid and solid problems in the standard FEM fashion. We note once more that the nodes discretizing the fluid and solid domains can be viewed as material particles which motion is tracked during the transient solution. | ||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| − | <li>Discretize the fluid and solid domains with a finite element mesh. The mesh generation process can be based on a standard Delaunay discretization [George (1991)<span id="citeF-13"></span>[[#cite-13|[13]]]] of the analysis domain using an initial collection of points which then become the mesh nodes. Alternatively, the nodes can be created during the mesh generation process using a front generation method [Irons (1970)<span id="citeF-24"></span>[[#cite-24|[24]]]; Thompson ''et al.'' (1999)<span id="citeF-42"></span>[[#cite-42|[42]]]]. </li> | + | <li>Discretize the fluid and solid domains with a finite element mesh. The mesh generation process can be based on a standard Delaunay discretization [George (1991) <span id="citeF-13"></span>[[#cite-13|[13]]]] of the analysis domain using an initial collection of points which then become the mesh nodes. Alternatively, the nodes can be created during the mesh generation process using a front generation method [Irons (1970) <span id="citeF-24"></span>[[#cite-24|[24]]]; Thompson ''et al.'' (1999) <span id="citeF-42"></span>[[#cite-42|[42]]]]. </li> |

| − | <li>Identify the external boundaries for both the fluid and solid domains. This is an essential step as some boundaries (such as the free surface in fluids) may be severely distorted during the solution process including separation and re-entering of nodes. The Alpha Shape method [Edelsbrunner and Mucke (2003)<span id="citeF-10"></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]]] is used for the boundary definition (see Section [[#7 Generation of a New Mesh|7]]). </li> | + | <li>Identify the external boundaries for both the fluid and solid domains. This is an essential step as some boundaries (such as the free surface in fluids) may be severely distorted during the solution process including separation and re-entering of nodes. The Alpha Shape method [Edelsbrunner and Mucke (2003) <span id="citeF-10"></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]]] is used for the boundary definition (see Section [[#7 Generation of a New Mesh|7]]). </li> |

<li>Solve the coupled Lagrangian equations of motion for the fluid and the solid domains. Compute the relevant state variables in both domains at each time step: velocities, pressure and viscous stresses in the fluid and displacements, stresses and strains in the solid. </li> | <li>Solve the coupled Lagrangian equations of motion for the fluid and the solid domains. Compute the relevant state variables in both domains at each time step: velocities, pressure and viscous stresses in the fluid and displacements, stresses and strains in the solid. </li> | ||

<li>Move the mesh nodes to a new position in terms of the time increment size. This step is typically a consequence of the solution process of step 3. </li> | <li>Move the mesh nodes to a new position in terms of the time increment size. This step is typically a consequence of the solution process of step 3. </li> | ||

| − | <li>Generate a new mesh if needed. The mesh regeneration process can take place after a prescribed number of time steps or when the actual mesh has suffered severe distorsions due to the Lagrangian motion. In our work we use an innovative mesh generation scheme based on the extended Delaunay tesselation (Section [[#7 Generation of a New Mesh|7]]) [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003b; 2004)<span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]],<span id="citeF-21"></span>[[#cite-21|21]],<span id="citeF-23"></span>[[#cite-23|23]]]]. </li> | + | <li>Generate a new mesh if needed. The mesh regeneration process can take place after a prescribed number of time steps or when the actual mesh has suffered severe distorsions due to the Lagrangian motion. In our work we use an innovative mesh generation scheme based on the extended Delaunay tesselation (Section [[#7 Generation of a New Mesh|7]]) [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003b; 2004) <span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]],<span id="citeF-21"></span>[[#cite-21|21]],<span id="citeF-23"></span>[[#cite-23|23]]]]. </li> |

<li>Go back to step 2 and repeat the solution process for the next time step. </li> | <li>Go back to step 2 and repeat the solution process for the next time step. </li> | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1"|(a) | + | | colspan="1" |(a) |

| − | | colspan="1"|(b) | + | | colspan="1" |(b) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[ | + | |[[File:Draft_Samper_860628002_8660_2a.JPG]] |

| + | |[[File:Draft_Samper_860628002_1006_2b.JPG]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure2c.png|300px|Breakage of a water column. (a) Discretization of the fluid domain and the solid walls. Boundary nodes are marked with circles. (b) and (c) Mesh in the fluid and solid domains at two different times.]] | + | | colspan="2" |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure2c.png|300px|Breakage of a water column. (a) Discretization of the fluid domain and the solid walls. Boundary nodes are marked with circles. (b) and (c) Mesh in the fluid and solid domains at two different times.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="2"|(c) | + | | colspan="2" |(c) |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

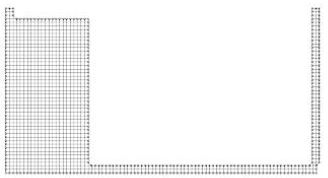

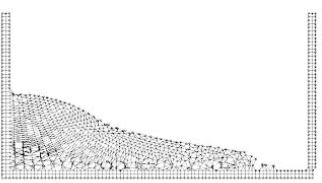

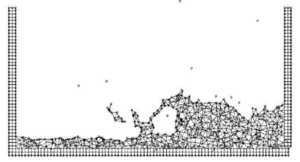

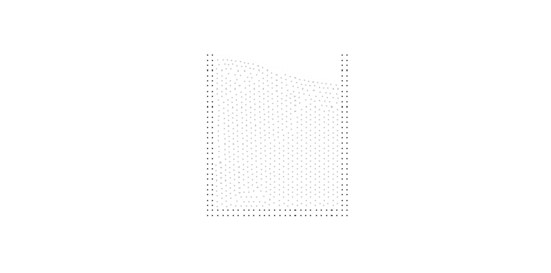

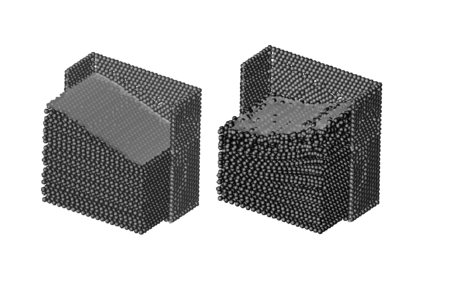

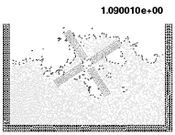

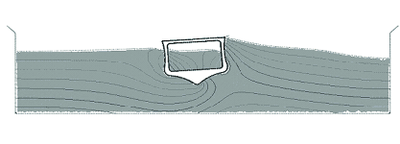

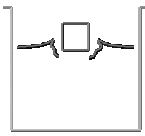

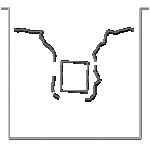

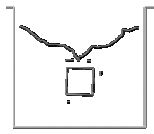

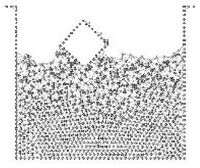

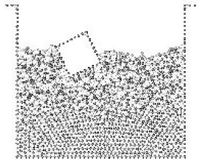

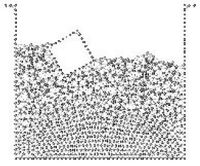

| colspan="2" | '''Figure 2:''' Breakage of a water column. (a) Discretization of the fluid domain and the solid walls. Boundary nodes are marked with circles. (b) and (c) Mesh in the fluid and solid domains at two different times. | | colspan="2" | '''Figure 2:''' Breakage of a water column. (a) Discretization of the fluid domain and the solid walls. Boundary nodes are marked with circles. (b) and (c) Mesh in the fluid and solid domains at two different times. | ||

| Line 84: | Line 85: | ||

==3 Lagrangian Equations for an Incompressible Fluid. FIC Formulation== | ==3 Lagrangian Equations for an Incompressible Fluid. FIC Formulation== | ||

| − | The standard infinitessimal equations for a viscous incompressible fluid can be written in a Lagrangian frame as [Oñate (1998); Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000) | + | The standard infinitessimal equations for a viscous incompressible fluid can be written in a Lagrangian frame as [Oñate (1998) <span id="citeF-27"></span>[[#cite-27|[27]]]; Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000) <span id="citeF-43"></span>[[#cite-43|[43]]]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | '''Momentum''' | ||

| + | <span id="eq-1"></span> | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 98: | Line 99: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | '''Mass balance''' | |

| − | + | <span id="eq-2"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 111: | Line 112: | ||

where | where | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-3"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 118: | Line 119: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| style="text-align: center;" | <math>r_{m_i} = \rho {\partial v_i \over \partial t} + {\partial \sigma _{ij} \over \partial x_j}-b_i\quad ,\quad \sigma _{ji}=\sigma _{ij}</math> | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>r_{m_i} = \rho {\partial v_i \over \partial t} + {\partial \sigma _{ij} \over \partial x_j}-b_i\quad ,\quad \sigma _{ji}=\sigma _{ij}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (3) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (3) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="eq-4"></span> | ||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| style="text-align: center;" | <math> r_d = {\partial v_i \over \partial x_i}\qquad i,j = 1, n_d </math> | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> r_d = {\partial v_i \over \partial x_i}\qquad i,j = 1, n_d </math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (4) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (4) | ||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

Above <math display="inline">n_d</math> is the number of space dimensions, <math display="inline">v_i</math> is the velocity along the ith global axis (<math display="inline">v_i = {\partial u_i \over \partial t}</math>, where <math display="inline">u_i</math> is the ''i''th displacement), <math display="inline">\rho </math> is the (constant) density of the fluid, <math display="inline">b_i</math> are the body forces, <math display="inline">\sigma _{ij}</math> are the total stresses given by <math display="inline">\sigma _{ij}=s_{ij}-\delta _{ij}p</math>, <math display="inline">p</math> is the absolute pressure (defined positive in compression) and <math display="inline">s_{ij}</math> are the viscous deviatoric stresses related to the viscosity <math display="inline">\mu </math> by the standard expression | Above <math display="inline">n_d</math> is the number of space dimensions, <math display="inline">v_i</math> is the velocity along the ith global axis (<math display="inline">v_i = {\partial u_i \over \partial t}</math>, where <math display="inline">u_i</math> is the ''i''th displacement), <math display="inline">\rho </math> is the (constant) density of the fluid, <math display="inline">b_i</math> are the body forces, <math display="inline">\sigma _{ij}</math> are the total stresses given by <math display="inline">\sigma _{ij}=s_{ij}-\delta _{ij}p</math>, <math display="inline">p</math> is the absolute pressure (defined positive in compression) and <math display="inline">s_{ij}</math> are the viscous deviatoric stresses related to the viscosity <math display="inline">\mu </math> by the standard expression | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-5"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 138: | Line 147: | ||

where <math display="inline">\delta _{ij}</math> is the Kronecker delta and the strain rates <math display="inline">\dot \varepsilon _{ij}</math> are | where <math display="inline">\delta _{ij}</math> is the Kronecker delta and the strain rates <math display="inline">\dot \varepsilon _{ij}</math> are | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-6"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 151: | Line 160: | ||

In the above all variables are defined at the current time <math display="inline">t</math> (current configuration). | In the above all variables are defined at the current time <math display="inline">t</math> (current configuration). | ||

| − | In our work we will solve a ''modified set of governing'' equations derived using a finite calculus (FIC) formulation. The FIC governing equations are [Oñate (1998; 2000; 2004); Oñate ''et al.'' (2001) | + | In our work we will solve a ''modified set of governing'' equations derived using a finite calculus (FIC) formulation. The FIC governing equations are [Oñate (1998; 2000; 2004) <span id="citeF-27"></span>[[#cite-27|[27]],<span id="citeF-28"></span>[[#cite-28|28]],<span id="citeF-29"></span>[[#cite-29|29]]]; Oñate ''et al.'' (2001) <span id="citeF-32"></span>[[#cite-32|[32]]]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | '''Momentum''' | ||

| + | <span id="eq-7"></span> | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 160: | Line 169: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>r_{m_i} - \underline{{1\over 2} h_j{\partial r_{m_i} \over \partial x_j} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>r_{m_i} - \underline{{1\over 2} h_j{\partial r_{m_i} \over \partial x_j}}=0 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (7) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (7) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | '''Mass balance''' | |

| − | + | <span id="eq-8"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 172: | Line 181: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>r_d - \underline{{1\over 2} h_j {\partial r_d \over \partial x_j} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>r_d - \underline{{1\over 2} h_j {\partial r_d \over \partial x_j}}=0 </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (8) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (8) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-9"></span> | |

The problem definition is completed with the following boundary conditions | The problem definition is completed with the following boundary conditions | ||

| Line 184: | Line 193: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>n_j \sigma _{ij} -t_i + \underline{{1\over 2} h_j n_j r_{m_i} | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>n_j \sigma _{ij} -t_i + \underline{{1\over 2} h_j n_j r_{m_i}}=0 \quad \hbox{on }\Gamma _t </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (9) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (9) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-10"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 201: | Line 210: | ||

and the initial condition is <math display="inline">v_j =v_j^0</math> for <math display="inline">t=t_0</math>. The standard summation convention for repeated indexes is assumed unless otherwise specified. | and the initial condition is <math display="inline">v_j =v_j^0</math> for <math display="inline">t=t_0</math>. The standard summation convention for repeated indexes is assumed unless otherwise specified. | ||

| − | In Eqs.(7) and (8) <math display="inline">t_i</math> and <math display="inline">v_j^p</math> are surface tractions and prescribed velocities on the boundaries <math display="inline">\Gamma _t</math> and <math display="inline">\Gamma _v</math>, respectively, <math display="inline">n_j</math> are the components of the unit normal vector to the boundary. | + | In Eqs.([[#eq-7|7]]) and ([[#eq-8|8]]) <math display="inline">t_i</math> and <math display="inline">v_j^p</math> are surface tractions and prescribed velocities on the boundaries <math display="inline">\Gamma _t</math> and <math display="inline">\Gamma _v</math>, respectively, <math display="inline">n_j</math> are the components of the unit normal vector to the boundary. |

| − | The <math display="inline">h_i's</math> in above equations are ''characteristic lengths'' of the domain where balance of momentum and mass is enforced. In Eq.(9) these lengths define the domain where equilibrium of boundary tractions is established. Details of the derivation of Eqs.(7)–(10) can be found in [Oñate (1998; 2000); Oñate ''et al.'' (2001)]. | + | The <math display="inline">h_i's</math> in above equations are ''characteristic lengths'' of the domain where balance of momentum and mass is enforced. In Eq.([[#eq-9|9]]) these lengths define the domain where equilibrium of boundary tractions is established. Details of the derivation of Eqs.([[#eq-7|7]])–([[#eq-10|10]]) can be found in [Oñate (1998; 2000) <span id="citeF-27"></span>[[#cite-27|[27]],<span id="citeF-28"></span>[[#cite-28|28]]]; Oñate ''et al.'' (2001) <span id="citeF-32"></span>[[#cite-32|[32]]]]. |

| − | Eqs.(7)–(10) are the starting point for deriving stabilized finite element methods to solve the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations in a Lagrangian frame of reference using equal order interpolation for the velocity and pressure variables [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2002; 2003a; 2003b; 2004); Oñate ''et al.'' (2003); Aubry ''et al.'' (2004)]. Application of the FIC formulation to finite element and meshless analysis of fluid flow problems can be found in [García and Oñate (2003); Oñate (2000; 2004); Oñate ''et al.'' (2000; 2004); Oñate and García (2001); Oñate and Idelsohn ( | + | Eqs.([[#eq-7|7]])–([[#eq-10|10]]) are the starting point for deriving stabilized finite element methods to solve the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations in a Lagrangian frame of reference using equal order interpolation for the velocity and pressure variables [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2002; 2003a; 2003b; 2004) <span id="citeF-19"></span>[[#cite-19|[19]]-<span id="citeF-21"></span>[[#cite-21|21]],<span id="citeF-23"></span>[[#cite-23|23]]]; Oñate ''et al.'' (2003) <span id="citeF-33"></span>[[#cite-33|[33]]]; Aubry ''et al.'' (2004) <span id="citeF-1"></span>[[#cite-1|[1]]]]. Application of the FIC formulation to finite element and meshless analysis of fluid flow problems can be found in [García and Oñate (2003 <span id="citeF-12"></span>[[#cite-12|[12]]]); Oñate (2000; 2004) <span id="citeF-28"></span>[[#cite-28|[28]],<span id="citeF-29"></span>[[#cite-29|29]]]; Oñate ''et al.'' (2000; 2004) <span id="citeF-31"></span>[[#cite-31|[31]],<span id="citeF-34"></span>[[#cite-34|34]]]; Oñate and García (2001) <span id="citeF-32"></span>[[#cite-32|[32]]]; Oñate and Idelsohn (1998) <span id="citeF-30"></span>[[#cite-30|[30]]]]. |

===3.1 Transformation of the mass balance equation. Integral governing equations=== | ===3.1 Transformation of the mass balance equation. Integral governing equations=== | ||

| − | The underlined term in Eq.(8) can be expressed in terms of the momentum equations. The new expression for the mass balance equation is (see Appendix) | + | The underlined term in Eq.([[#eq-8|8]]) can be expressed in terms of the momentum equations. The new expression for the mass balance equation is (see [[#Appendix|Appendix]]) |

| − | + | <span id="eq-11"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 222: | Line 231: | ||

with | with | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-12"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 233: | Line 242: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | The <math display="inline">\tau _i</math>'s in Eq.(11), when scaled by the density, are termed ''intrinsic time parameters''. Similar values for <math display="inline">\tau _i</math> (usually <math display="inline">\tau _i =\tau </math> is taken) are used in other works from ad-hoc extensions of the 1D advective-diffusive problem [Codina ''et al.'' (1998); Codina and Blasco (2000); Codina (2002); Codina and Zienkiewicz (2002); Cruchaga and Oñate (1997; 1999); Donea and Huerta (2003); Franca and Frey (1992); Hansbo and Szepessy (1990); Hughes ''et al.'' (1986; 1989; 1994); Oñate (1998; 2000; 2004); Sheng ''et al.'' (1996); Storti ''et al.'' ( | + | The <math display="inline">\tau _i</math>'s in Eq.([[#eq-11|11]]), when scaled by the density, are termed ''intrinsic time parameters''. Similar values for <math display="inline">\tau _i</math> (usually <math display="inline">\tau _i =\tau </math> is taken) are used in other works from ad-hoc extensions of the 1D advective-diffusive problem [Codina ''et al.'' (1998) <span id="citeF-4"></span>[[#cite-4|[4]]]; Codina and Blasco (2000) <span id="citeF-5"></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]]; Codina (2002) <span id="citeF-3"></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]]; Codina and Zienkiewicz (2002) <span id="citeF-6"></span>[[#cite-6|[6]]]; Cruchaga and Oñate (1997; 1999) <span id="citeF-7"></span>[[#cite-7|[7]],<span id="citeF-8"></span>[[#cite-8|8]]]; Donea and Huerta (2003) <span id="citeF-9"></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]]; Franca and Frey (1992) <span id="citeF-11"></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]]; Hansbo and Szepessy (1990) <span id="citeF-15"></span>[[#cite-15|[15]]]; Hughes ''et al.'' (1986; 1989; 1994) <span id="citeF-16"></span>[[#cite-16|[16]]-<span id="citeF-18"></span>[[#cite-18|18]]]; Oñate (1998; 2000; 2004) <span id="citeF-27"></span>[[#cite-27|[27]]-<span id="citeF-29"></span>[[#cite-29|29]]]; Sheng ''et al.'' (1996) <span id="citeF-36"></span>[[#cite-36|[36]]]; Storti ''et al.'' (1995) <span id="citeF-37"></span>[[#cite-37|[37]]]; Tezduyar ''et al.'' (1992) <span id="citeF-41"></span>[[#cite-41|[41]]]; Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000) <span id="citeF-43"></span>[[#cite-43|[43]]]]. |

| − | At this stage it is no longer necessary to retain the stabilization terms in the momentum equations. These terms are critical in Eulerian formulations to stabilize the numerical solution for high values of the convective terms. In the Lagrangian formulation the convective terms dissapear from the momentum equations and the FIC terms in these equations are just useful to derive the form of the mass balance equation given by Eq.(11) and can be disregarded there onwards. Consistenly, the stabilization terms are also neglected in the Neuman boundary conditions (eqs.(9)). | + | At this stage it is no longer necessary to retain the stabilization terms in the momentum equations. These terms are critical in Eulerian formulations to stabilize the numerical solution for high values of the convective terms. In the Lagrangian formulation the convective terms dissapear from the momentum equations and the FIC terms in these equations are just useful to derive the form of the mass balance equation given by Eq.([[#eq-11|11]]) and can be disregarded there onwards. Consistenly, the stabilization terms are also neglected in the Neuman boundary conditions (eqs.([[#eq-9|9]])). |

The weighted residual expression of the final form of the momentum and mass balance equations can be written as | The weighted residual expression of the final form of the momentum and mass balance equations can be written as | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-13"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 248: | Line 257: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (13) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (13) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-14"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 261: | Line 270: | ||

where <math display="inline">\delta v_i</math> and <math display="inline">q</math> are arbitrary weighting functions equivalent to virtual velocity and virtual pressure fields. | where <math display="inline">\delta v_i</math> and <math display="inline">q</math> are arbitrary weighting functions equivalent to virtual velocity and virtual pressure fields. | ||

| − | The <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> term in Eq.(14) and the deviatoric stresses and the pressure terms within <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> in Eq.(13) are integrated by parts to give | + | The <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> term in Eq.([[#eq-14|14]]) and the deviatoric stresses and the pressure terms within <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> in Eq.([[#eq-13|13]]) are integrated by parts to give |

| − | + | <span id="eq-15"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 272: | Line 281: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (15) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (15) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-16"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 283: | Line 292: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | In Eq.(15) <math display="inline">\delta \dot \varepsilon _{ij}</math> are virtual strain rates. Note that the boundary term resulting from the integration by parts of <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> in Eq.(16) has been neglected as the influence of this term in the numerical solution has been found to be negligible. | + | In Eq.([[#eq-15|15]]) <math display="inline">\delta \dot \varepsilon _{ij}</math> are virtual strain rates. Note that the boundary term resulting from the integration by parts of <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> in Eq.([[#eq-16|16]]) has been neglected as the influence of this term in the numerical solution has been found to be negligible. |

===3.2 Pressure gradient projection=== | ===3.2 Pressure gradient projection=== | ||

| − | The computation of the residual terms in Eq.(16) can be simplified if we introduce now the pressure gradient projections <math display="inline">\pi _i</math>, defined as | + | The computation of the residual terms in Eq.([[#eq-16|16]]) can be simplified if we introduce now the pressure gradient projections <math display="inline">\pi _i</math>, defined as |

| − | + | <span id="eq-17"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 299: | Line 308: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | We express now <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> in Eq.(17) in terms of the <math display="inline">\pi _i</math> which then become additional variables. The system of integral equations is therefore augmented in the necessary number of equations by imposing that the residual <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> vanishes within the analysis domain (in an average sense). This gives the final system of governing equation as: | + | We express now <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> in Eq.([[#eq-17|17]]) in terms of the <math display="inline">\pi _i</math> which then become additional variables. The system of integral equations is therefore augmented in the necessary number of equations by imposing that the residual <math display="inline">r_{m_i}</math> vanishes within the analysis domain (in an average sense). This gives the final system of governing equation as: |

| − | + | <span id="eq-18"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 310: | Line 319: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (18) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (18) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-19"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 320: | Line 329: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (19) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (19) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-20"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 331: | Line 340: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | with <math display="inline">i,j,k=1,n_d</math>. | + | with <math display="inline">i,j,k=1,n_d</math>. In Eqs.([[#eq-20|20]]) <math display="inline">\delta \pi _i</math> are appropriate weighting functions and the <math display="inline">\tau _i</math> weights are introduced for symmetry reasons. |

==4 Finite Element Discretization== | ==4 Finite Element Discretization== | ||

| Line 338: | Line 347: | ||

We choose <math display="inline">C^\circ </math> continuous interpolations of the velocities, the pressure and the pressure gradient projections <math display="inline">\pi _i</math> over each element with <math display="inline">n</math> nodes. The interpolations are written as | We choose <math display="inline">C^\circ </math> continuous interpolations of the velocities, the pressure and the pressure gradient projections <math display="inline">\pi _i</math> over each element with <math display="inline">n</math> nodes. The interpolations are written as | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-21"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 349: | Line 358: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | where <math display="inline">\bar {(\cdot )}^j</math> denotes nodal variables and <math display="inline">N_j</math> are the shape functions [Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000)]. More details of the mesh discretization process and the choice of shape functions are given in Section | + | where <math display="inline">\bar {(\cdot )}^j</math> denotes nodal variables and <math display="inline">N_j</math> are the shape functions [Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000) <span id="citeF-43"></span>[[#cite-43|[43]]]]. More details of the mesh discretization process and the choice of shape functions are given in Section [[#7 Generation of a New Mesh|7]]. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | Substituting the approximations ([[#eq-21|21]]) into Eqs.([[#eq-19|19]]-[[#eq-20|20]]) and choosing a Galerkin form with <math display="inline">\delta v_i =q=\delta \pi _i =N_i</math> leads to the following system of discretized equations | ||

| + | <span id="eq-22"></span> | ||

| + | <span id="eq-22a"></span> | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 362: | Line 372: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (22a) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (22a) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-22b"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 372: | Line 382: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (22b) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (22b) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-22c"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 384: | Line 394: | ||

where | where | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-23"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 395: | Line 405: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | is the internal nodal force vector derived from the momentum equations, <math display="inline">s</math> is the deviatoric stress vector, | + | is the internal nodal force vector derived from the momentum equations, <math display="inline">s</math> is the deviatoric stress vector, <math display="inline">B</math> is the strain rate matrix and <math display="inline">{m} = [1,1,0]^T</math> for 2D problems. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | This vector and the rest of the matrices and vectors in Eqs.([[#eq-22|22]]) are assembled from the element contributions given by (for 2D problems) | ||

| + | <span id="eq-24"></span> | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 411: | Line 421: | ||

with <math display="inline">i,j=1,n</math> and <math display="inline">k,l=1,2</math>. | with <math display="inline">i,j=1,n</math> and <math display="inline">k,l=1,2</math>. | ||

| − | As usual the deviatoric stresses <math display="inline">s_{ij}</math> are related to the strain rates <math display="inline">\dot \varepsilon _{ij}</math> by Eq.(5) | + | As usual the deviatoric stresses <math display="inline">s_{ij}</math> are related to the strain rates <math display="inline">\dot \varepsilon _{ij}</math> by Eq.([[#eq-5|5]]) |

| − | It can be shown that the system of Eqs.(22) leads to a stabilized numerical solution. For details see [Oñate ''et al.'' (2003)]. | + | It can be shown that the system of Eqs.([[#eq-22|22]]) leads to a stabilized numerical solution. For details see [Oñate ''et al.'' (2003) <span id="citeF-33"></span>[[#cite-33|[33]]]]. |

| − | + | '''Remark 1''' | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | Eq.([[#eq-22a|22a]]) can be written in a more explicit form in terms of the velocity and pressure variables as | ||

| + | <span id="eq-25"></span> | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 430: | Line 440: | ||

where | where | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-26"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 441: | Line 451: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | where | + | where <math display="inline">D</math> is the constitutive matrix. For 2D problems |

| − | + | <span id="eq-27"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 456: | Line 466: | ||

A simple and effective iterative algorithm can be obtained by splitting the pressure from the momentum equations as follows | A simple and effective iterative algorithm can be obtained by splitting the pressure from the momentum equations as follows | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-28"></span> | |

| + | <span id="eq-28a"></span> | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 466: | Line 477: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (28a) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (28a) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-28b"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 477: | Line 488: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | In Eq.(28a) | + | In Eq.([[#eq-28a|28a]]) |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 488: | Line 499: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | and <math display="inline">\alpha </math> is a variable taking values equal to zero or one. For <math display="inline">\alpha =0</math>, <math display="inline">\delta p \equiv p^{n+1,j}</math> and for <math display="inline">\alpha =1</math>, <math display="inline">\delta p =\Delta p</math>. Note that in both cases the sum of Eqs.(28a) and (28b) gives the time discretization of the momentum equations with the pressures computed at <math display="inline">t^{n+1}</math>. | + | and <math display="inline">\alpha </math> is a variable taking values equal to zero or one. For <math display="inline">\alpha =0</math>, <math display="inline">\delta p \equiv p^{n+1,j}</math> and for <math display="inline">\alpha =1</math>, <math display="inline">\delta p =\Delta p</math>. Note that in both cases the sum of Eqs.([[#eq-28|28a]]) and ([[#eq-28b|28b]]) gives the time discretization of the momentum equations with the pressures computed at <math display="inline">t^{n+1}</math>. |

In above equations and in the following superindex <math display="inline">j</math> denotes an iteration number within each time step. | In above equations and in the following superindex <math display="inline">j</math> denotes an iteration number within each time step. | ||

| − | The value of <math display="inline">\bar {v}^{n+1,j}</math> from Eq.(28b) is substituted now into Eq.(22b) to give | + | The value of <math display="inline">\bar {v}^{n+1,j}</math> from Eq.([[#eq-28b|28b]]) is substituted now into Eq.([[#eq-22b|22b]]) to give |

| − | + | <span id="eq-29"></span> | |

| + | <span id="eq-29a"></span> | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 505: | Line 517: | ||

The product <math display="inline">{G}^T {M}^{-1}{G}</math> can be approximated by a laplacian matrix, i.e. | The product <math display="inline">{G}^T {M}^{-1}{G}</math> can be approximated by a laplacian matrix, i.e. | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-29b"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 519: | Line 531: | ||

A semi-implicit algorithm can be derived as follows. For each iteration:<br/> | A semi-implicit algorithm can be derived as follows. For each iteration:<br/> | ||

| − | + | <span id="s-1"></span> | |

| − | '''Step 1''' Compute <math display="inline">{v}^*</math> from Eq.(28a) with <math display="inline">{M}={M}_d</math> where subscript <math display="inline">d</math> denotes hereonwards a diagonal matrix. | + | '''Step 1''' |

| + | Compute <math display="inline">{v}^*</math> from Eq.([[#eq-28a|28a]]) with <math display="inline">{M}={M}_d</math> where subscript <math display="inline">d</math> denotes hereonwards a diagonal matrix. | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | + | <span id="s-2"></span> | |

| − | '''Step 2''' Compute <math display="inline">\delta \bar {p}</math> and <math display="inline">{p}^{n+1}</math> from Eq.(29a) as | + | '''Step 2''' |

| − | + | Compute <math display="inline">\delta \bar {p}</math> and <math display="inline">{p}^{n+1}</math> from Eq.([[#eq-29a|29a]]) as | |

| + | <span id="eq-30"></span> | ||

| + | <span id="eq-30a"></span> | ||

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 537: | Line 552: | ||

The pressure <math display="inline">p^{n+1,j}</math> is computed as follows | The pressure <math display="inline">p^{n+1,j}</math> is computed as follows | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-30b"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 547: | Line 562: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (30b) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (30b) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | <span id="s-3"></span> | ||

| + | '''Step 3''' | ||

| + | Compute <math display="inline"> \bar{v}^{n+1,j}</math> from Eq.([[#eq-28b|28b]]) with <math display="inline">{M}={M}_d</math> | ||

| − | + | <span id="s-4"></span> | |

| − | + | '''Step 4''' | |

| − | '''Step 4''' Compute <math display="inline"> \bar{\boldsymbol \pi }^{n+1,j}</math> from Eq.(22c) as | + | Compute <math display="inline"> \bar{\boldsymbol \pi }^{n+1,j}</math> from Eq.([[#eq-22c|22c]]) as |

| − | + | <span id="eq-31"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 561: | Line 579: | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (31) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (31) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <span id="s-5"></span> | |

'''Step 5''' Solve for the movement of the structure due to the fluid flow forces.<br/> | '''Step 5''' Solve for the movement of the structure due to the fluid flow forces.<br/> | ||

This implies solving the dynamic equations of motion for the structure written as | This implies solving the dynamic equations of motion for the structure written as | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-32"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 576: | Line 594: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | where <math display="inline">{d}</math> and <math display="inline">\ddot {d}</math> are respectively the displacement and acceleration vectors of the nodes discretizing the structure, <math display="inline">{M}_s</math> and <math display="inline">{K}_s</math> are the mass and stiffness matrices of the structure and <math display="inline">{f}_{ext}</math> is the vector of external nodal forces accounting for the fluid flow forces induced by the pressure and the viscous stresses. Clearly the main driving forces for the motion of the structure is the fluid pressure which acts as normal a surface traction on the structure. Indeed Eq.(32) can be augmented with an appropriate damping term. The form of all the relevant matrices and vectors can be found in standard books on FEM for structural analysis [Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000)]. | + | where <math display="inline">{d}</math> and <math display="inline">\ddot {d}</math> are respectively the displacement and acceleration vectors of the nodes discretizing the structure, <math display="inline">{M}_s</math> and <math display="inline">{K}_s</math> are the mass and stiffness matrices of the structure and <math display="inline">{f}_{ext}</math> is the vector of external nodal forces accounting for the fluid flow forces induced by the pressure and the viscous stresses. Clearly the main driving forces for the motion of the structure is the fluid pressure which acts as normal a surface traction on the structure. Indeed Eq.([[#eq-32|32]]) can be augmented with an appropriate damping term. The form of all the relevant matrices and vectors can be found in standard books on FEM for structural analysis [Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2000) <span id="citeF-43"></span>[[#cite-43|[43]]]]. |

| − | Solution of Eq.(32) in time can be performed using implicit or fully explicit time integration algorithms. In both cases the values of the nodal displacements, velocities and accelerations of the structure at <math display="inline">t^{n+1}</math> are found for the <math display="inline">j</math>th iteration. | + | Solution of Eq.([[#eq-32|32]]) in time can be performed using implicit or fully explicit time integration algorithms. In both cases the values of the nodal displacements, velocities and accelerations of the structure at <math display="inline">t^{n+1}</math> are found for the <math display="inline">j</math>th iteration. |

| + | <span id="s-6"></span> | ||

'''Step 6''' | '''Step 6''' | ||

Update the mesh nodes in a Lagrangian manner. From the definition of the velocity <math display="inline">v_i ={\partial u_i \over \partial t}</math> it is deduced. | Update the mesh nodes in a Lagrangian manner. From the definition of the velocity <math display="inline">v_i ={\partial u_i \over \partial t}</math> it is deduced. | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-33"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 594: | Line 613: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | <span id="s-7"></span> | ||

'''Step 7''' | '''Step 7''' | ||

| − | Generate a new mesh. This can be effectively performed using the procedure described in Section 6. | + | Generate a new mesh. This can be effectively performed using the procedure described in Section [[#6 Treatment of Contact Between Fluid and Solid Interfaces|6]]. |

| + | <span id="s-8"></span> | ||

'''Step 8''' | '''Step 8''' | ||

| − | Check the convergence of the velocity and pressure fields in the fluid and the displacements strains and stresses in the structure. If convergence is achieved move to the next time step, otherwise return to step 1 for the next iteration with <math display="inline">j+1 \to j</math>. | + | Check the convergence of the velocity and pressure fields in the fluid and the displacements strains and stresses in the structure. If convergence is achieved move to the next time step, otherwise return to step [[#s-1|1]] for the next iteration with <math display="inline">j+1 \to j</math>. |

Despite the motion of the nodes within the iterative process, in general there is no need to regenerate the mesh at each iteration. A new mesh is typically generated after a prescribed number of converged time steps, or when the nodal displacements induce significant geometrical distorsions in some elements. ''In the examples presented in the paper the mesh in the fluid domain has been regenerated at each time step''. | Despite the motion of the nodes within the iterative process, in general there is no need to regenerate the mesh at each iteration. A new mesh is typically generated after a prescribed number of converged time steps, or when the nodal displacements induce significant geometrical distorsions in some elements. ''In the examples presented in the paper the mesh in the fluid domain has been regenerated at each time step''. | ||

| − | The boundary conditions are applied as follows. No condition is applied in the computation of the fractional velocities <math display="inline">{v}^*</math> in Eq.(28a). The prescribed velocities at the boundary are applied when solving for <math display="inline">\bar{v}^{n+1,j}</math> in step 3. The prescribed pressures at the boundary are imposed by making the pressure increments zero at the relevant boundary nodes and making <math display="inline">\bar{p}^n</math> equal to the prescribed pressure values. | + | The boundary conditions are applied as follows. No condition is applied in the computation of the fractional velocities <math display="inline">{v}^*</math> in Eq.([[#eq-28a|28a]]). The prescribed velocities at the boundary are applied when solving for <math display="inline">\bar{v}^{n+1,j}</math> in step [[#s-3|3]]. The prescribed pressures at the boundary are imposed by making the pressure increments zero at the relevant boundary nodes and making <math display="inline">\bar{p}^n</math> equal to the prescribed pressure values. |

| − | Details of the treatment of the contact conditions at the solid-fluid interface are given in Section 8 [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2004)]. | + | Details of the treatment of the contact conditions at the solid-fluid interface are given in Section [[#8 Identification of Boundary Surfaces|8]] [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2004) <span id="citeF-23"></span>[[#cite-23|[23]]]]. |

| − | Note that solution of steps 1, 3 and 4 does not require the solution of a system of equations as a diagonal form is chosen for <math display="inline">M</math> and <math display="inline">\hat {M}</math>. The whole solution process within a time step can be linearized by choosing <math display="inline">\theta _1 = \theta _2 =0</math> and now the iteration loop is no longer necessary. The implicit solution for <math display="inline">\theta _1 = \theta _2 =1</math> is however very effective as larger time steps can be used. This requires some iterations within steps 1 | + | Note that solution of steps [[#s-1|1]], [[#s-3|3]] and [[#s-4|4]] does not require the solution of a system of equations as a diagonal form is chosen for <math display="inline">M</math> and <math display="inline">\hat {M}</math>. The whole solution process within a time step can be linearized by choosing <math display="inline">\theta _1 = \theta _2 =0</math> and now the iteration loop is no longer necessary. The implicit solution for <math display="inline">\theta _1 = \theta _2 =1</math> is however very effective as larger time steps can be used. This requires some iterations within steps [[#s-1|1]]-[[#s-8|8]] until converged values for the fluid and solid variables and the new position of the mesh nodes at time <math display="inline">n+1</math> are found. |

In the examples presented in the paper the time increment size has been chosen as | In the examples presented in the paper the time increment size has been chosen as | ||

| − | + | <span id="eq-34"></span> | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 624: | Line 645: | ||

where <math display="inline">h_i^{\min }</math> is the distance between node <math display="inline">i</math> and the closest node in the mesh. | where <math display="inline">h_i^{\min }</math> is the distance between node <math display="inline">i</math> and the closest node in the mesh. | ||

| − | + | '''Remark 2''' | |

| − | Although not explicitely mentioned for <math display="inline">\theta _1=1</math> all matrices and vectors in Eqs.(28) | + | Although not explicitely mentioned for <math display="inline">\theta _1=1</math> all matrices and vectors in Eqs.([[#eq-28|28]])-([[#eq-32|32]]) are computed at the final configuration <math display="inline">\Omega ^{n+1,j}</math>. This means that the integration domain changes for each iteration and, hence, all the terms involving space derivatives must be updated at each iteration. This problem dissapears if <math display="inline">\Omega ^n</math> is taken as the reference configuration (<math display="inline">\theta _1=0</math>) as this remains fixed during the iteration. The penalty to pay in this case, however, is the evaluation of the Jacobian matrix at each iterations [Aubry ''et al.'' (2004) <span id="citeF-1"></span>[[#cite-1|[1]]]]. |

==6 Treatment of Contact Between Fluid and Solid Interfaces== | ==6 Treatment of Contact Between Fluid and Solid Interfaces== | ||

| Line 634: | Line 655: | ||

==7 Generation of a New Mesh== | ==7 Generation of a New Mesh== | ||

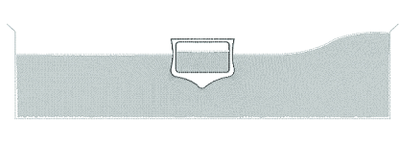

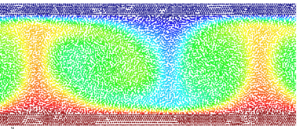

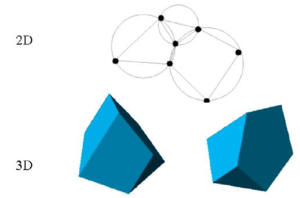

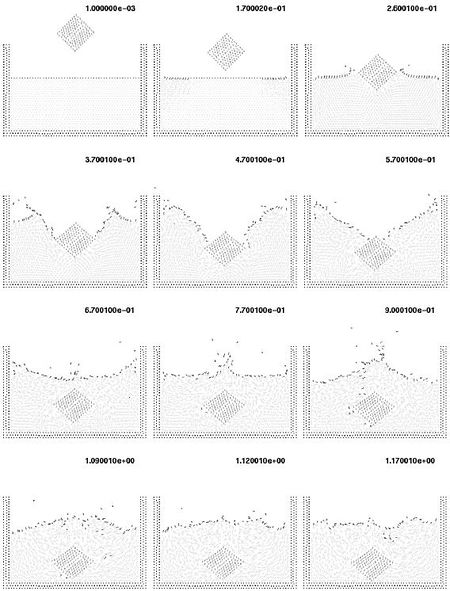

| − | One of the key points for the success of the Lagrangian flow formulation described here is the fast regeneration of a mesh at every time step on the basis of the position of the nodes in the space domain. In our work the mesh is generated using the so called extended Delaunay tesselation (EDT) presented in [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003c; 2004)]. The EDT allows one to generate non standard meshes combining elements of arbitrary polyhedrical shapes (triangles, quadrilaterals and other polygons in 2D and tetrahedra, hexahedra and arbitrary polyhedra in 3D) in a computing time of order <math display="inline">n</math>, where <math display="inline">n</math> is the total number of nodes in the mesh (Figure 3). The <math display="inline">C^\circ </math> continuous shape functions of the elements can be simply obtained using the so called meshless finite element interpolation (MFEM). Details of the mesh generation procedure and the derivation of the MFEM shape functions can be found in [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003c; 2004)]. | + | One of the key points for the success of the Lagrangian flow formulation described here is the fast regeneration of a mesh at every time step on the basis of the position of the nodes in the space domain. In our work the mesh is generated using the so called extended Delaunay tesselation (EDT) presented in [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003c; 2004) <span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]],<span id="citeF-23"></span>[[#cite-23|23]],<span id="citeF-24"></span>[[#cite-24|24]]]]. The EDT allows one to generate non standard meshes combining elements of arbitrary polyhedrical shapes (triangles, quadrilaterals and other polygons in 2D and tetrahedra, hexahedra and arbitrary polyhedra in 3D) in a computing time of order <math display="inline">n</math>, where <math display="inline">n</math> is the total number of nodes in the mesh (Figure [[#img-3|3]]). The <math display="inline">C^\circ </math> continuous shape functions of the elements can be simply obtained using the so called meshless finite element interpolation (MFEM). Details of the mesh generation procedure and the derivation of the MFEM shape functions can be found in [Idelsohn ''et al.'' (2003a; 2003c; 2004) <span id="citeF-20"></span>[[#cite-20|[20]],<span id="citeF-23"></span>[[#cite-23|23]],<span id="citeF-24"></span>[[#cite-24|24]]]]. |

Once the new mesh has been generated the numerical solution is found at each time step using the fractional step algorithm described in the previous section. | Once the new mesh has been generated the numerical solution is found at each time step using the fractional step algorithm described in the previous section. | ||

| Line 643: | Line 664: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure3.png| | + | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure3.png|300px|Generation of non standard meshes combining different polygons (in 2D) and polyhedra (in 3D) using the extended Delaunay technique.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="1" | '''Figure 3:''' Generation of non standard meshes combining different polygons (in 2D) and polyhedra (in 3D) using the extended Delaunay technique. | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 3:''' Generation of non standard meshes combining different polygons (in 2D) and polyhedra (in 3D) using the extended Delaunay technique. | ||

| Line 654: | Line 675: | ||

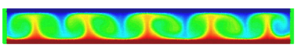

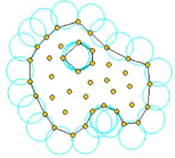

The use of the extended Delaunay partition makes it easier to recognize boundary nodes. | The use of the extended Delaunay partition makes it easier to recognize boundary nodes. | ||

| − | Considering that the nodes follow a variable <math display="inline">h(x)</math> distribution, where <math display="inline">h(x)</math> is the minimum distance between two nodes, the following criterion has been used. ''All nodes on an empty sphere with a radius greater than <math>\alpha h</math>, are considered as boundary nodes''. In practice, <math display="inline">\alpha </math> is a parameter close to, but greater than one. Note that this criterion is coincident with the Alpha Shape concept [Edelsbrunner and Mucke (1999)]. | + | Considering that the nodes follow a variable <math display="inline">h(x)</math> distribution, where <math display="inline">h(x)</math> is the minimum distance between two nodes, the following criterion has been used. ''All nodes on an empty sphere with a radius greater than <math>\alpha h</math>, are considered as boundary nodes''. In practice, <math display="inline">\alpha </math> is a parameter close to, but greater than one. Note that this criterion is coincident with the Alpha Shape concept [Edelsbrunner and Mucke (1999) <span id="citeF-10"></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]]]. |

Once a decision has been made concerning which nodes are on the boundaries, the boundary surface must be defined. It is well known that in 3-D problems the surface fitting for a number of nodes is not unique. For instance, four boundary nodes on the same sphere may define two different boundary surfaces, a concave one and a convex one. | Once a decision has been made concerning which nodes are on the boundaries, the boundary surface must be defined. It is well known that in 3-D problems the surface fitting for a number of nodes is not unique. For instance, four boundary nodes on the same sphere may define two different boundary surfaces, a concave one and a convex one. | ||

| Line 660: | Line 681: | ||

In this work, the boundary surface is defined by all the polyhedral surfaces (or polygons in 2D) having all their nodes on the boundary and belonging to just one polyhedron. | In this work, the boundary surface is defined by all the polyhedral surfaces (or polygons in 2D) having all their nodes on the boundary and belonging to just one polyhedron. | ||

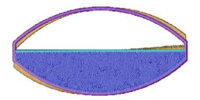

| − | Figure 4 shows example of the boundary recognition using the Alpha Shape technique. | + | Figure [[#img-4|4]] shows example of the boundary recognition using the Alpha Shape technique. |

<div id='img-4'></div> | <div id='img-4'></div> | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure4a.png| | + | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure4a.png|175px|]] |

| − | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_616988227_1121_monograph-Fig2.png| | + | |[[Image:Draft_Samper_616988227_1121_monograph-Fig2.png|175px|Examples of boundary recognition with the Alpha Shape method. Empty circles with radius greater than αh(x) define the boundary particles.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="2" | '''Figure 4:''' Examples of boundary recognition with the Alpha Shape method. Empty circles with radius greater than <math>\alpha h(x)</math> define the boundary particles. | | colspan="2" | '''Figure 4:''' Examples of boundary recognition with the Alpha Shape method. Empty circles with radius greater than <math>\alpha h(x)</math> define the boundary particles. | ||

| Line 675: | Line 696: | ||

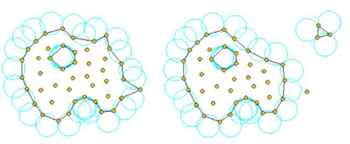

The method described also allows one to identify isolated fluid particles outside the main fluid domain. These particles are treated as part of the external boundary where the pressure is fixed to the atmospheric value. | The method described also allows one to identify isolated fluid particles outside the main fluid domain. These particles are treated as part of the external boundary where the pressure is fixed to the atmospheric value. | ||

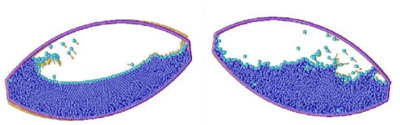

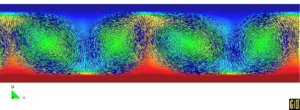

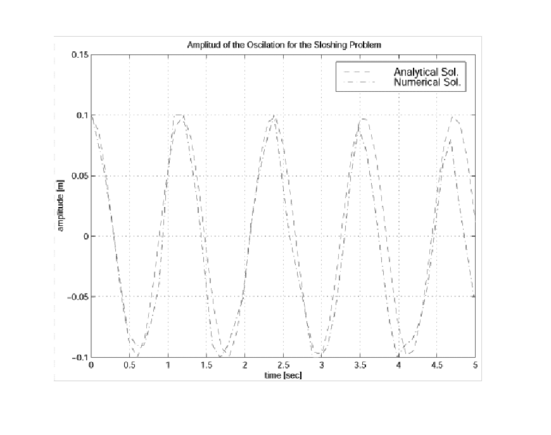

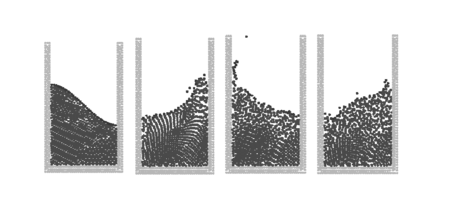

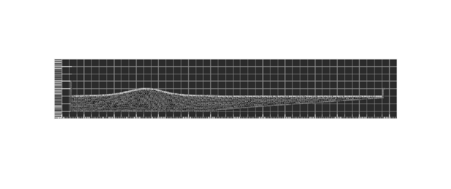

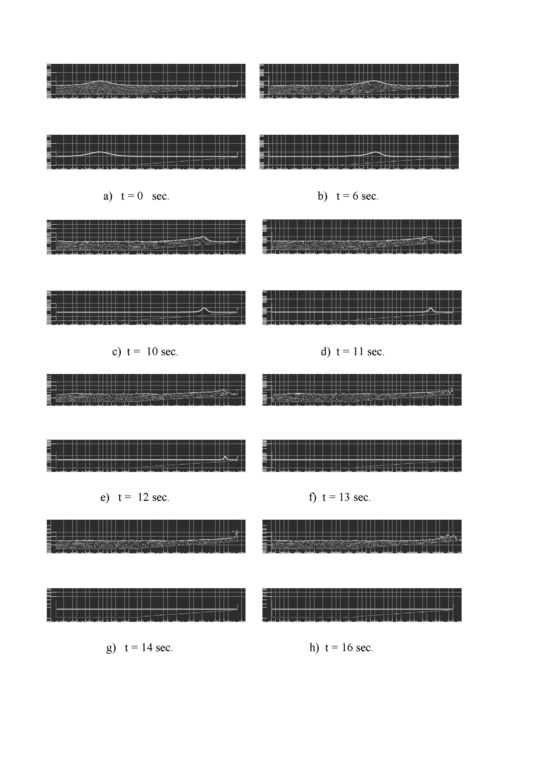

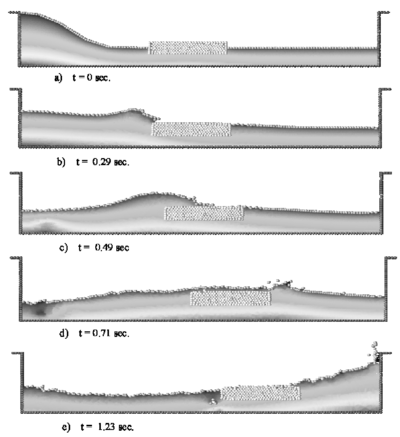

| − | Figure 5 shows a schematic example of the process to identify individual particles (or a group of particles) starting from a given collection of nodes. A practical application of the method for identifying free surface particles is shown in Figure 6. The example corresponds to the analysis of the motion of a fluid within an oscilating ellipsoidal container. Note that the method captures the individual water drops departuring from the free surface during the fluid motion. | + | Figure [[#img-5|5]] shows a schematic example of the process to identify individual particles (or a group of particles) starting from a given collection of nodes. A practical application of the method for identifying free surface particles is shown in Figure [[#img-6|6]]. The example corresponds to the analysis of the motion of a fluid within an oscilating ellipsoidal container. Note that the method captures the individual water drops departuring from the free surface during the fluid motion. |

<div id='img-5'></div> | <div id='img-5'></div> | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure5.png| | + | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure5.png|350px|Identification of individual particles (or a group of particles) starting from a given collection of nodes.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="1" | '''Figure 5:''' Identification of individual particles (or a group of particles) starting from a given collection of nodes. | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 5:''' Identification of individual particles (or a group of particles) starting from a given collection of nodes. | ||

| Line 690: | Line 711: | ||

| style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;"| (a) | | style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;"| (a) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure6a.png| | + | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure6a.png|200px|]] |

|- | |- | ||

|style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;"| (b) | |style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;"| (b) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure6b.png| | + | |[[Image:draft_Samper_616988227-Figure6b.png|400px|]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| colspan="1" | '''Figure 6:''' Motion of a liquid within an oscillating container. (a) Original distribution of particles (nodes) prior to the oscillation. (b) Position of the liquid particles at two different times. The boundary particles representing the free surface, the fluid drops and the container wall are plotted with a lighter colour. Arrows indicate velocity vectors for each particle. | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 6:''' Motion of a liquid within an oscillating container. (a) Original distribution of particles (nodes) prior to the oscillation. (b) Position of the liquid particles at two different times. The boundary particles representing the free surface, the fluid drops and the container wall are plotted with a lighter colour. Arrows indicate velocity vectors for each particle. | ||

| Line 701: | Line 722: | ||

==9 Modelling a “Rigid” Structure as a Viscous Fluid== | ==9 Modelling a “Rigid” Structure as a Viscous Fluid== | ||

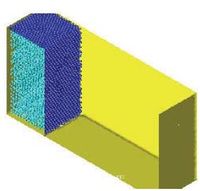

| − | A simple and yet effective way to analyze the rigid motion of solid bodies in fluids with the Lagrangian flow description is to model the solid as a fluid with a viscosity much higher than that of the surrounding fluid. The fractional step scheme of Section 5 can be readily applied skipping now step 5 and solving now for the simultaneous motion of both fluid domains (the actual fluid and the fictitious fluid modelling the quasi-rigid body). | + | A simple and yet effective way to analyze the rigid motion of solid bodies in fluids with the Lagrangian flow description is to model the solid as a fluid with a viscosity much higher than that of the surrounding fluid. The fractional step scheme of Section [[#5 Fractional Step Method for Fluid-Structure Interaction Analysis|5]] can be readily applied skipping now step [[#s-5|5]] and solving now for the simultaneous motion of both fluid domains (the actual fluid and the fictitious fluid modelling the quasi-rigid body). Examples of this type are presented in Sections [[#10.3 Wave breaking on a beach|10.3]] and [[#10.4 Fixed ship hit by wave|10.4.]] |

| − | Indeed this approach can be further extended to account for the elastic deformation of the solid treated now as a visco-elastic fluid. This will however introduce some complexity in the formulation and the full coupled FSI scheme described in Section 5 is preferable. | + | Indeed this approach can be further extended to account for the elastic deformation of the solid treated now as a visco-elastic fluid. This will however introduce some complexity in the formulation and the full coupled FSI scheme described in Section [[#5 Fractional Step Method for Fluid-Structure Interaction Analysis|5]] is preferable. |

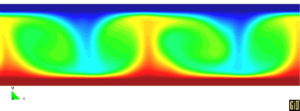

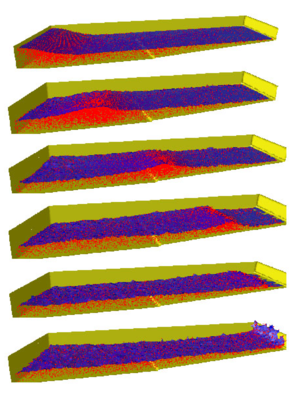

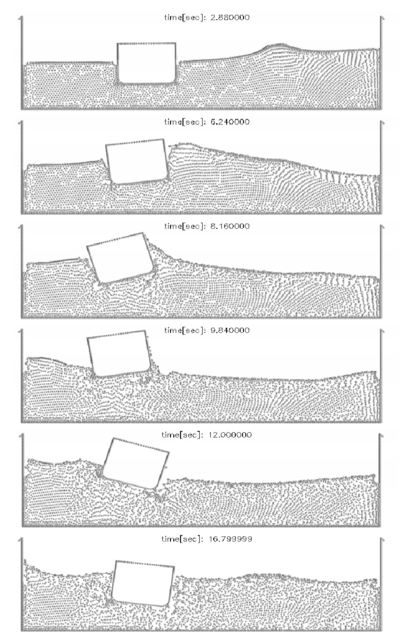

==10 Examples== | ==10 Examples== | ||

| − | The examples chosen show the applicability of the PFEM to solve problems involving large fluid motions and FSI situations. The fractional step algorithm of Section 5 with <math display="inline">\theta _2 =1</math> and <math display="inline">\alpha =1</math> has been used in all cases. | + | The examples chosen show the applicability of the PFEM to solve problems involving large fluid motions and FSI situations. The fractional step algorithm of Section [[#5 Fractional Step Method for Fluid-Structure Interaction Analysis|5]] with <math display="inline">\theta _2 =1</math> and <math display="inline">\alpha =1</math> has been used in all cases. |

| − | In examples 10.1 | + | In examples [[#10.1 Collapse of a water column|10.1]]-[[#10.10 Rigid cube falling into a water container|10.10]] a value of <math display="inline">\theta _1=1</math> has been chosen. This basically means that the final configuration <math display="inline">\Omega ^{n+1,j}</math> has been taken as the reference configuration at each iteration. In example [[#10.11 The Rayleigh-Bénard Instability|10.11]] <math display="inline">\theta _1=0</math> has been selected and, hence, the initial configuration <math display="inline">\Omega ^n</math> has been taken as a fixed reference configuration for all the iterations within a time step. |

<div id='img-7'></div> | <div id='img-7'></div> | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[ | + | |[[File:Draft_Samper_860628002_2785_7a.JPG|200px]] |

| − | |- | + | |[[File:Draft_Samper_860628002_9636_7b.JPG|200px]] |

| − | | | + | |- |

| − | | | + | |[[File:Draft_Samper_860628002_8641_7c.JPG|200px]] |

| − | + | |[[File:Draft_Samper_860628002_5207_7d.JPG|200px]] | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | |[[File:Draft_Samper_860628002_9807_7e.JPG|200px]] | |