(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== In th...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 605450879 to Marin et al 2014a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 12:43, 29 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

In this article we approach the topic of collaborative learning by means of the creation and maintenance of personal learning environments and networks (PLE and PLN) and their integration within institutional virtual learning environments (VLE) as strategies to enhance and foster collaborative learning. We take an educational point of view: the student learns independently and carries out activities in groups to achieve common goals. Our aim is to experiment with didactical methodologies of integration between the institutional VLE and PLE, and to analyze the university students’ construction of PLE. Due to its importance in facilitating and fostering collaborative learning, special emphasis is placed on the construction of the personal learning network. We performed a design-based research on an academic course for Primary teachers. The results show that the students construct their PLE and PLN using newly acquired knowledge and that an appropriate methodological integration takes place between these environments and the institutional VLE for integrated learning. As conclusion, we propose an integrative methodological model for collaborative learning as a good practice.

1. Introduction

The university of the future should be an institution that provides education to a greater part of the population throughout their lives and which generates knowledge that is of service to educational needs (Salinas, 2012). This has led to the setting-up of various learning scenarios that are currently being tried and researched. These learning scenarios are being developed within the concept of Personal Learning Environments (PLE) and open learning environments (Brown, 2010; Hannafin, Land & Oliver, 1999; Sclater, 2008). The concept of PLE is defined, from a pedagogical point of view, as the set of tools, materials and human resources that a person is aware of and uses for life-long learning (Adell & Castañeda, 2010; Attwell, 2007; Hilzensauer & Schaffert, 2008). The functions of the PLE that we took into account in this work, as indicated by Wheeler (2009) are: information management (related to personal knowledge management), creation of content and connections with others (which is known as the personal learning or knowledge network). PLE involve a change in education in favour of student-centred learning by overcoming the limitations of virtual learning/teaching environments (VLE) based on learning management systems (LMS). PLE, therefore, enable students to take control and manage their own learning, taking into account decisions on their personal learning goals, management of their own learning (content and process management), communication with others in the learning process and everything else that contributes to achieving their goals (Salinas, 2013).

We started on the basis of the theory known as LaaN, Learning as a Network, which includes various concepts and theories, such as connectivism (learning as a connection), the complexity theory (understanding the dynamics and uncertainty of knowledge in current society), the concept of double loop learning (learning about errors and research) and, in particular, knowledge environments (Chatti, Schroeder & Jarke, 2013; Chatti 2013), considering that «learning is the continuous creation of a personal knowledge network» (Adell & Castañeda, 2013:38).

This Personal Learning Network (PLN or PKN) consists of the sum of connections with other people’s PLE (their tools and strategies for reading, reflection and relationships), that make up knowledge environments (Chatti et al., 2012) and whose interaction produces the development and enabling of strategies for the actual PLE and, therefore, are central to learning and professional development (Couros, 2010; Downes, 2010; Sloep & Berlanga, 2011). The idea of the PLN is that each person contributes their knowledge so that what is most important is not what each person has in their PLE, but the sharing of those resources. The LaaN theory is «an attempt to draw up a theoretical foundation for learning and teaching which will start up the construction and enrichment of the actual PLE» (Adell & Castañeda, 2013: 38).

In addition, PLE can also be used as bases for constructive learning (Adell & Castañeda, 2013), given that they are able to comply with the five features for activities leading to significant learning proposed by Jonassen et al. (2003), they are active, constructive, intentional, authentic and collaborative. A collaborative environment (CSCL, Computer Supported Collaborative Learning) is based on group work that begins with interaction and collaboration (Johnson & Johnson, 1996; Lipponen, 2002), provides communication tools and makes human resources from various fields available (teachers, experts, colleagues, etc.). Collaboration as a learning strategy is based on working in heterogeneous groups of people with similar knowledge levels to achieve communal goals and carry out tasks together, with there being a positive interdependence between them (Dillenbourg, 1999; Prendes, 2007). There is no single correct answer in collaborative tasks. Instead, there are several ways of arriving at the result and, to achieve this, students must share and reach agreements, an event that helps them to be socially and intellectually more self-sufficient and mature (Bruffee, 1995).

This study is framed within a wider research project that seeks to define and test various didactic strategies for the integration of PLE and VLE taking into account different learning environments (formal, informal and casual) on the basis of previous works (Marín, 2013; Marín & Salinas, in press; Marín, Salinas & de Benito, 2012, 2013; Salinas, Marín & Escandell, in press).

In this article, on the basis of these ideas, we present an experiment in which methodologies that seek to encourage collaboration and integration of these environments within the university (PLE and PLN on the one hand, and VLE on the other) are put into practice, as well as some of the results observed during the process.

2. Methodology for the study

The study was carried out on a group of teachers and students on the course «Technological media and resources for primary education» in the third year of studies for the Primary Teacher’s Degree at the University of the Balearic Islands. The material is worth 6 ECTS points and the intention is to develop skills in the use of technology that will enable teaching and learning processes at school.

The course group was made up of three teachers and 192 students organised into three large groups of approximately 70 and ten practical groups of approximately 25.

All the students had prior knowledge of technological tools given that they had studied a course relating to education technology during the first year (Information and Communication Technologies applied to Primary Education).

According to an initial questionnaire, answered by 179 students, it can be seen that the majority are women (71%), are under 24 years old (70%) and are frequent users of social networks (mainly Facebook), generic search engines (Google) and video web sites (Youtube). This creates an internet user profile that is basically that of a consumer – they consume information and communicate with their friends but hardly ever produce content.

The development of the course was based on learning principles centred on student and methodologies focusing on collaboration and social construction of knowledge (Salinas, Pérez & de Benito, 2008). It was structured around the following activities, relating to the development of the student’s PLE, according to the basic functions indicated by Wheeler (2009): a) development of a design and development-based work group project; b) creation of personal learning networks; and c) use of appropriate internet technology to locate and manage information, create content and share knowledge. In addition, a methodological strategy was organised that would allow integration of the use of the PLE into the VLE, in which the VLE offers access to basic documentation on the course and large group or private communication spaces and the development of the PLE enables development of information management processes and participation in external learning networks.

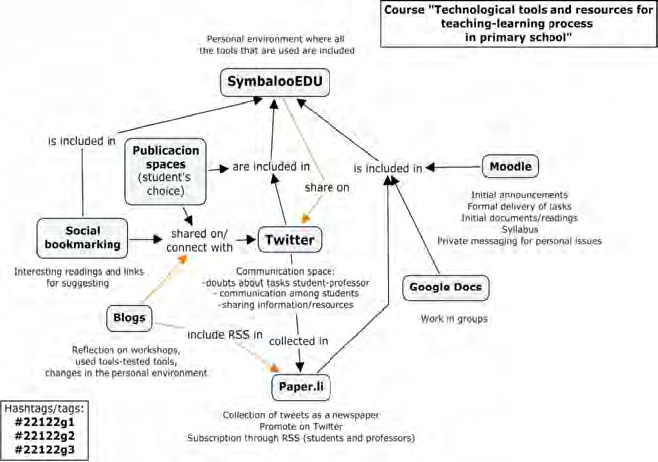

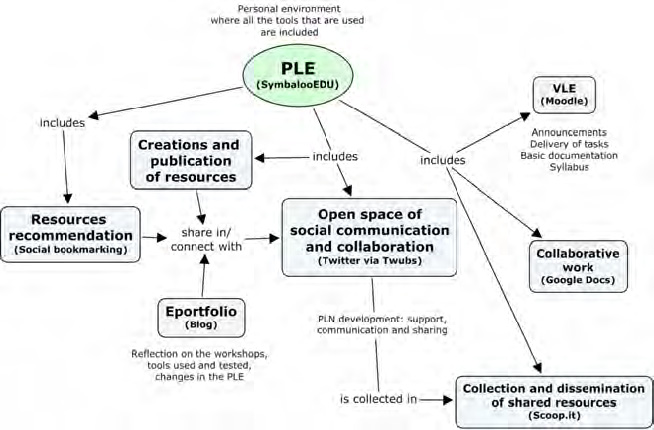

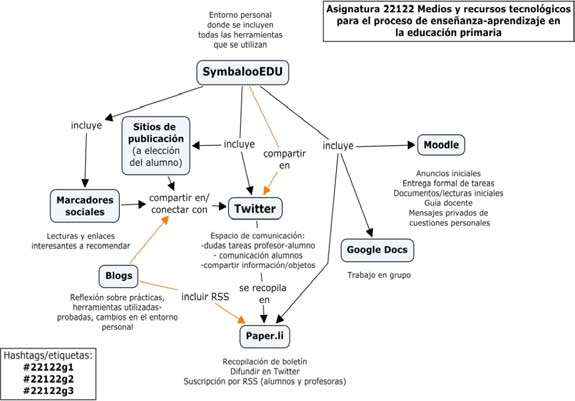

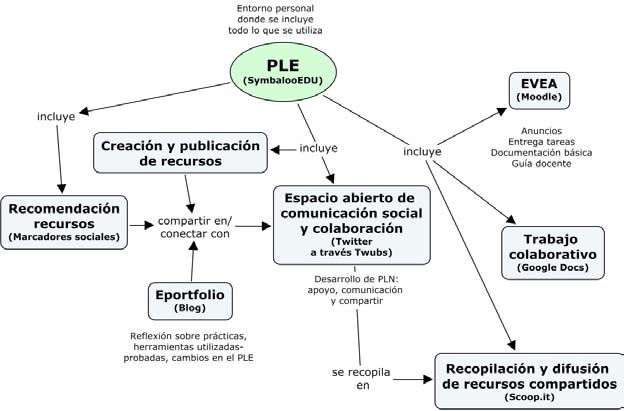

The elements of the strategy shown in figure 1, based on course tasks and some features of collaborative learning are set out below.

• Access course study guides. Content is presented structured into concept maps that represent and interconnect basic concepts and provide supplementary resources (reading, videos, examples, etc). Hints are given for development of the work project and practical activities. These materials are provided by the teachers and are available on the Moodle-based VLE.

• Locate, access and organise supplementary materials using generic search engines (eg, Google), social bookmarking (eg, delicious), specific search engines (eg, Google Scholar), content recovery (eg, materials published/shared on Twitter by one person or another). Students are encouraged to find useful information to carry out course activities and organise information organisation systems.

• Personally organise and manage information (using personal organisation tools, RSS subscription to blogs/web sites, following in Twitter, use of SymbalooEDU to organise new information). Furthermore, within the framework of the course, the student is offered shared resources and links (paper.li).

Activities related to creating content:

• Organise the PLE itself using SymbalooEDU, in which each student organises the tools and resources that they use to carry out the course tasks and other environments.

• Create a personal blog that gives an account of the learning activities carried out during the course. Entries include materials developed by students in different formats (text, audio, video, texting, interactive multimedia, etc) and reflections on teaching practice.

• Develop and publish a collaborative group project that requires the creation of didactic materials for primary education (interactive multimedia, video and WebQuest). This project follows the features of collaborative learning according to Johnson, Johnson & Holubec (1999) – existence of positive interdependence, individual and group responsibility, stimulating interaction, availability of the necessary personal and group attitudes and abilities, and group assessment. The project is delivered through the VLE.

Finally, in relation to connection with others, the following activities are included:

• Interaction and collaboration with others through the VLE in relation to the activities proposed in forums (debates) or via private messaging to the teacher or other students. These activities are in line with the features indicated by Onrubia (1997) for collaborative learning – they are group tasks, require contribution by everyone and have sufficient resources to be completed.

• Share and circulate the results of activities using the personal blog and sending messages on Twitter, using the hashtags set up for the course (chat on Twitter), to other people and/or colleagues to circulate their work on the blog and share interesting resources, encouraging interaction, participation and communication (Ingram & Hathorn, 2004).

• Communicate and collaborate on educational virtual communities and social networks or others of interest (outside the course hashtag on Twitter).

• Widen their personal learning network (PLN) by following people of interest, on Twitter as well as other social networks or virtual communities or via RSS subscriptions, with teachers, experts and people related to field of interest, etc.

2.1. Tools for information collection

The tools for information collection are qualitative as well as quantitative with the aim of enabling interpretation and relevance of the information. The tools are as follows:

• Analysis of documents relating to integration of the PLE elements. These documents are amongst those produced by the students during the course. On the one hand, group projects and personal blog entries, and on the other, the evolution of the PLE’s construction, represented graphically by screen shots of their SymbalooEDU.

• Observation of the student’s reaction in relation to implementation of didactic integration with respect to the personal learning network. This is done by carrying out a non-exhaustive descriptive and quantitative analysis of interactions on Twitter. The number of log-ons, comments between students, following people inside and outside the course, interactions aimed at sharing resources and activities, etc, are taken into account. A descriptive observation of the dynamic of the PLN in the blogs is also reviewed.

2.2. Study stages

The experience is carried out in four stages, following the methodology of design and development (Reeves, 2000; 2006; Van-den-Akker, 1999):

• Stage 1. Analysis of the situation and definition of the problem. Precedent research on techno-educational integration of PLE and VLE is reviewed. This is defined as the need to improve and optimise teaching/learning processes with the aim of integrating all fields of learning and centre on strategies that focus on the student’s learning.

• Stage 2. Development of solutions. Together with the teacher in charge of the course, a methodological strategy for didactic integration of the PLE and VLE is designed, which has previously been described. The elements of the strategy that are the least known are worked on with the teachers.

• Stage 3. Implementation and assessment. This stage puts into practice the strategy designed for the course, while at the same time the process is followed up and changes for iterative improvement are made to the strategy (eg, technical difficulties in the use of paper.li and Twitter meant proposing the use of other tools). At the start of the course a PLE workshop is held with students and they are asked to put the SymbalooEDU screen shots representing their PLE on their blogs at the start and end of the course. Periodically, entries on personal blogs are collected and SymbalooEDU screen shots on the blogs are saved after following RSS. A content analysis is made of the screen shots by counting the number of blocks included and according to type in accordance with the three PLE functions. A descriptive analysis is made on the selection and inclusion of tools from the group projects, included in the VLE, and blog entries.

Furthermore, tweets made with the course’s hashtag are also collected using an automatic tweet collector system (Rowfeeder). Afterwards, a content analysis is carried out using the tweet count and they are coded according to type. Later interaction on the blog of the people identified as most active on Twitter is examined, reviewing the comments on their blogs.

• Stage 4. Document production and design principles. Assessment of the strategy using the data collected leads to the proposal for a didactic integration model for the student’s PLE and the VLE.

3. Results

3.1. PLE construction

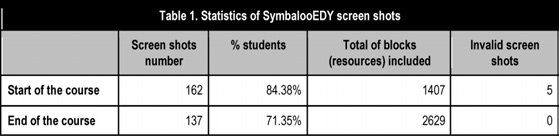

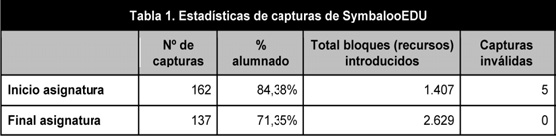

With respect to students’ evolution in the PLE, the following table shows the main statistics to be taken into account for SymbalooEDU screen shots and the level of participation at the start and end of the course.

The image given by this count gives us an idea about the type of tools used by the students at the beginning and end of the course on their PLE, whether they used them, or considered them interesting for use now or in the not too distant future.

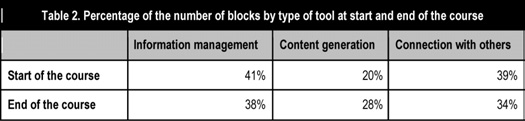

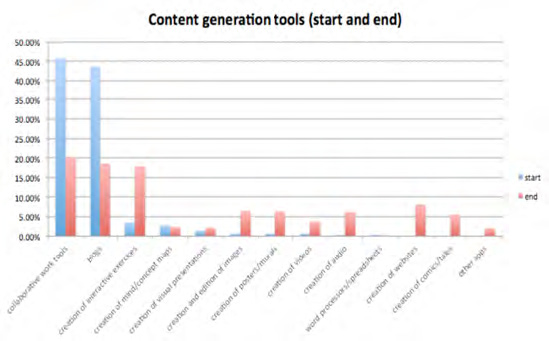

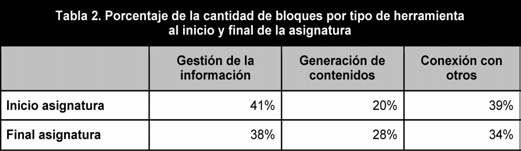

The evolution of the percentage number of blocks per resource type is shown below.

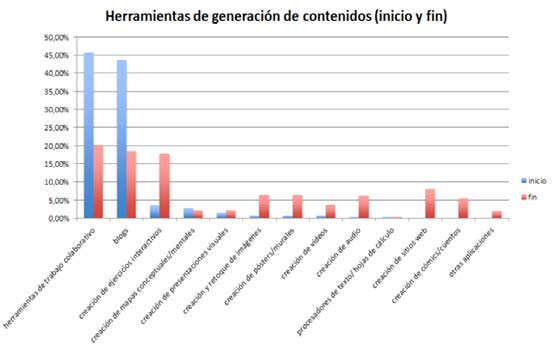

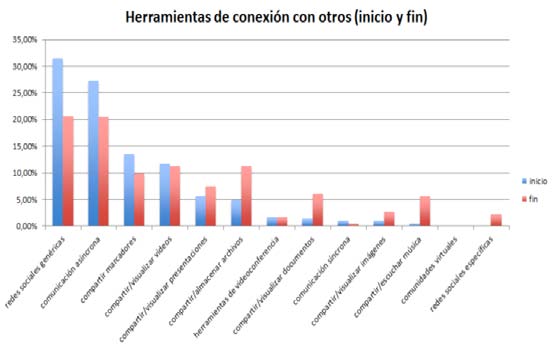

In spite of the fact that the evolution of the number of blocks per type of tool does not undergo serious changes (the most significant is the increase from 20% to 28% in blocks referring to content generation tools), a significant increase in the number of resources included at the start (101) and end (144) taking into account the various types can be seen.

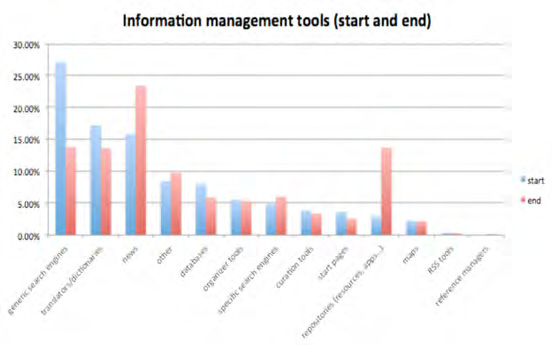

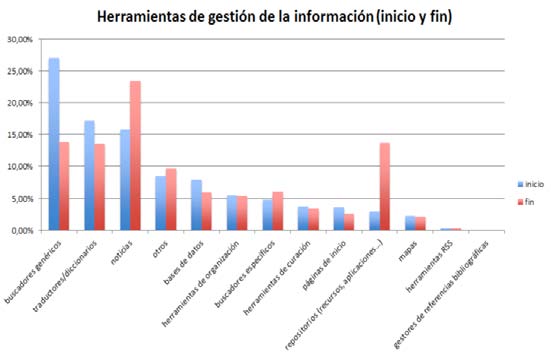

Looking at each type, as more specific statistics, notable differences can be seen between the tools and links used at the start and finish of the course, in spite of the fact that some remain the same.

With respect to information management resources, a highlight is the use of tools relating to locating relevant information for developing the course project, such as news links (many of which were related to the application of technology in education), learning banks (eg, educational activities) and search engines. We can see an increase in the first two. Some students included SymbalooEDU on their home pages as tools for personal organisation. This is interesting because information organisation and management is one of the PLE’s aims.

The greatest increase is seen in content generation tools. Given that the course mainly worked on educational content generation for primary education, many students included applications in their PLE that they considered useful for that purpose. Among the blocks included, highlights were collaborative creation and interactive exercise creation tools, blogs, web site creation, audio, image creation, walls, comics and videos. A wide variety of tools can be seen within each category, although the most frequently used are small in number.

At the start of the course, the most frequently used content generation tools were blogs (Blogger) and collaborative work tools (Google Drive). At the end of the course, these tools were still commonly used as they continue to be used during the course and were found to be useful, but there is also evidence of an increase in other content generation tools, as indicated above.

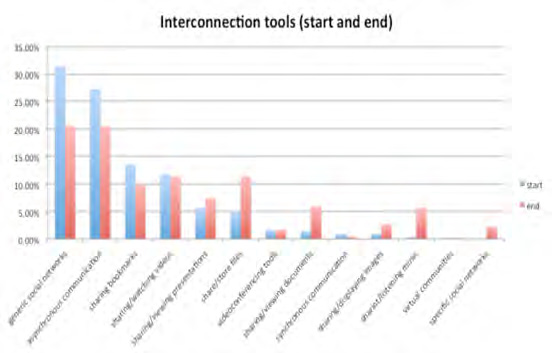

Finally, social networks and asynchronous communication tools stand out in relation to communicating with others. An increase in the tools needed to share course activities on the blog can be seen (eg, tools for sharing files, videos, visual presentations, text documents, etc.). It can also be seen that in the category of generic social networks, compared to the start, there was a majority inclusion of the students’ PLE on Twitter.

3.2. Development of the PLN

Regarding the development of the personal learning network, the use of Twitter by students was mainly taken into account. A total of 1986 tweets using the hashtags set up were counted, without taking into account repeats. In total, 189 of the students in the three groups took part, 47 of whom already had an account on that social network.

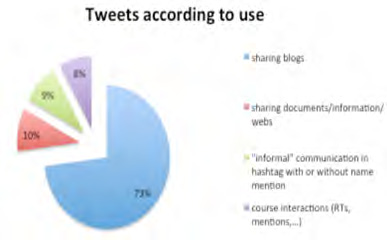

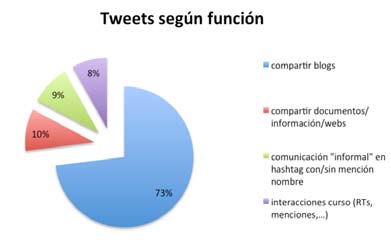

The average number of tweets per person was 10.51 (the minimum was 1 and the maximum 112), the trend was 10 and the density was low (0.11), as the greater number of interactions came from just a few authors. These were those configured as «group leaders». These people were significant as they acted as the catalyst for the group on the social network and encouraged participation by other colleagues. The 1986 tweets were divided up according to their use. The results can be seen below:

• 1451 tweets (73%) shared the results of course activities with other the other students, as was indicated in the initial instructions for the course.

• 190 tweets (10%) shared resources of interest to the rest of the course group. This content was related to that being worked on in class. 37 of these 190 tweets produced interaction with people outside the course (teachers, educational organisations, etc) by retweets or citations.

• 182 tweets (9%) were informal communications, with these considered to be messages to the whole group (greetings) and comments or dialogue with other students about the course (asking for help, questions, etc.).

• 163 tweets (8%) were recorded relating to interaction between students: retweets to colleagues or comments on jointly written blog entries, the group project, etc.

In addition, the number of followers and followed was reviewed. It turned out that the average number of followers for each student was 38.38 and followed, 61.39. Regarding those followed, out of the 189 students who took part on Twitter with their group’s hashtag for the course, 82 started to follow people/organisations outside the course. Therefore, in many cases, students enriched their use of the social network by going further than the formal environment, and particularly into the informal.

Based on the percentage of non-obligatory participation (interactions not directed at sharing the blog) (average: 2.83), those taking part with more than 5 tweets were taken into account. Those who went over this number were discounted if their interactions were the type citing joint work in blog entries (tweets not aimed at boosting the social space). In this way, a total of 13 people were counted, 9 students from the first group, 2 from the second group and 1 from the third group.

In addition, the dynamic of each group on Twitter was different. The active students in the first group, and to a lesser extent in the third group, aimed to share resources and comment on them, while the second group was more of an informal help space. In this case, it was seen that the students’ PLN was created around the blogs, as one of them acted as mentor and the others followed and were supported by the mentor’s explanations. On the other hand, no significant interaction was noticed between the groups.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Throughout the course the VLE was the bridge between the student’s PLE and the educational institution. It was used, above all, as an initial portal although almost all the learning process was developed using external elements that made up or became part of the student’s PLE (blogs, Twitter, etc). In addition, the VLE was didactically integrated into the student’s PLE naturally.

Furthermore, the evolution in the student’s construction of the PLE and PLN was confirmed. They developed procedures based on locating and managing information that would be useful for solving problems, creating content and communicating with the others. During this process well-known tools were used and new ones were continuously selected. Tools used in other environments were integrated and the spaces created within the framework of the course were extrapolated to other contexts.

During this evolution in management of the actual learning process, the students experienced the passage from being passive consumers of information and resources to being creators of content and materials in a variety of formats (Hilzensauer & Schaffert, 2008). This variety responds to the methodological strategy for the course that promotes content creation while at the same time giving independence so that it is the student –or group– who chooses the tools that are the most appropriate for the needs of the activity and its features.

Furthermore, foundations have been laid for the creation of personal learning networks in as much as the students have learned to take part in social networks, organise a social learning network, and participate in a sharing culture. Nevertheless, it is still necessary to overcome some challenges such as the level of participation and the degree of involvement in order to develop a truly collaborative process based on interaction and communication (Kirschner, 2002). What has been seen were various types of networks but confined to the group for the course with occasional external, support-based interaction, distribution of filtered resources and redistribution of contributions, whether their own or from others.

The impact of the experience on students’ learning arising from implementing the strategy was assessed as positive, as it promotes the student’s independence while learning, as well as collaborative knowledge construction based on the development of the group project and networks constructed around the course. These learning networks have huge potential that should be valued as a strategy for methodological change towards meaningful ways of learning based on problem solving or project development.

This experience enabled the development and evaluation of social knowledge construction processes, encouraging the student: a) to search for information, identify problems, acquire filtering criteria, interconnect and locate relevant data and distribute useful information; b) acknowledge and express their personal viewpoint (ideas and progress); and c) share this with the group and be able to change their point of view, adopt new perspectives, clarify points of disagreement, debate, negotiate agreements (Bruffee, 1995) and, finally, formulate and present knowledge (Stahl, 2000). Therefore, we propose a methodological organisation model as good practice for collaborative learning, with a suggested tool for each element in brackets.

The PLE, as the central element, includes the spaces and processes marked out for its uses (Wheeler, 2009): content creation, whether individual (e-portfolio, tool selection) or group (using collaborative work and communication tools), information management (individual and collaborative selection and recommendation of resources) and connection with others (using an open space for social communication and collaboration to create learning communities for collaborative knowledge construction).

Compared to the initial model, the proposed changes to tools with respect to the technical difficulties with Twitter and paper.li are included: introduction of content aggregation systems (Scoop.it, Twubs) for better information and PLN management and the tools that are the subject of this course (generation of educational materials for primary education).

Acknowledgments

This work is framed within the research project EDU2011-25499 «Methodological strategies for integrating institutional virtual environments, personal and social learning», developed by the Educational Technology Group (GTE) of the University of the Balearic Islands since 2012 and funded by the Ministry of Education and Science of Spain, within the National Programme for Fundamental Research.

References

Adell, J. & Castañeda, L. (2010). Los Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje (PLEs): una nueva manera de entender el aprendizaje. In R. Roig Vila & M. Fiorucci (Eds.), Claves para la investigación en innovación y calidad educativas. La integración de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación y la Interculturalidad en las aulas. Stumenti di ricerca per l’innovaziones e la qualità in ámbito educativo. La tecnologie dell’informazione e della comunicazione e l’interculturalità nella scuola (pp. 19-30). Alcoy: Marfil / Roma TRE Università degli Studi. (http://hdl.handle.net/10201/17247) (10-05-2013).

Adell, J. & Castañeda, L. (2013). El ecosistema pedagógico de los PLEs. In L. Casta-ñeda & J. Adell (Eds.), Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en red (pp. 29-51). Alcoy: Marfil. (http://digitum.um.es/xmlui/bitstream/10201/30409/1/capitulo2.pdf) (10-07-2013).

Attwell, G. (2007). Personal learning environments - the future of eLearning? In eLearning Papers, 2(1), 1-8. (www.elearningeuropa.info/files/media/media11561.pdf) (10-05-2013).

Brown, S. (2010). From VLEs to learning webs: the implications of Web 2.0 for learning and teaching. Interactive Learning Environments, 18(1), 1-10. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10494820802158983).

Bruffee, K. (1995). Sharing our toys - Cooperative learning versus collaborative learning. Revista Change, 27(1), 12-18. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1995.9937722)

Chatti, M.A. (2013). The LaaN Theory. In S. Downes, G. Siemens y R. Kop (Eds.), Personal learning environments, networks, and knowledge. (www.elearn.rwth-aachen.de/dl1151|Mohamed_Chatti_LaaN_preprint.pdf) (07-05-2013).

Chatti, M.A., Schroeder, U. & Jarke, M. (2012). LaaN: Convergence of Knowledge Management and Technology-enhanced Learning. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 5(2), 177-189. (DOI: http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/TLT.2011.33).

Couros, A. (2010). Developing Personal Learning Networks for Open and Social Learning. In G. Veletsianos (Ed.), Emerging Technologies in Distance Education. (pp. 109–128). Canada: AU Press, Athabasca University.

Dillenbourg, P. (1999). Collaborative Learning Cognitive and computational Ap-proaches Advances in learning and instructional series. Oxford (UK): Pierre Per-gamon.

Downes, S. (2010). Learning Networks and Connective Knowledge. Collective Intelli-gence and ELearning 20 Implications of Web Based Communities and Networking (pp. 1-26). IGI Publishing. (http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-729-4.ch001).

Hannafin, M.J. Land, S. & Oliver, K. (1999). Open Learning Environments: Founda-tions, Methods and Models. In C.M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-Design Theories and Models. A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory. (Volume II, pp. 115–140). Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Hilzensauer, W. & Schaffert, S. (2008). On the way towards Personal Learning Environments: Seven crucial aspects. In Elearning Papers, 9. (www.elearningeuropa.info/files/media/media15971.pdf) (10-05-2013).

Ingram, A. & Hathorn L. (2004). Methods for analyzing collaboration in online communications. In T. Roberts (Ed), Online Collaborative Learning: Theory and Practice (pp. 215-241). Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing. (http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59140-174-2.ch010).

Johnson, D. & Johnson, R. (1996). Cooperation and the Use of Technology. In M.J. Spector, D.M. Merrill, J. Van-Merrienboer & M.P. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (vol. 1, pp. 785-812). New York: Routledge.

Johnson, D., Johnson, J. & Holubec, E. (1999). El aprendizaje cooperativo en el aula. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Jonassen, D.H., Howland, J.L., Moore, J.L. & Marra, R.M. (2003). Learning to Solve Problems with Technology: A Constructivist Perspective. Upper Saddle River (New Jersey): Merrill Prentice Hall.

Kirschner, P.A. (2002). Can we support CSCL? Educational, Social and Technological Affordances for Learning. In P.A. Kirschner (Ed.), Three Worlds of CSCL: Can We Support CSCL? (pp. 7-47). Heerlen (The Netherlands): Open University of the Netherlands. (http://hdl.handle.net/1820/1618) (17-08-2013).

Lipponen, L. (2002), Exploring Foundations for Computer-supported Collaborative Learning, CSCL '02 Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Support for Collaborative Learning: Foundations for a CSCL Community, pp. 72-81, (http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1658627) (17-08-2013).

Marín, V.I. & Salinas, J. (in press). First Steps in the Development of a Model for Integrating Formal and Informal Learning in Virtual Environments. In Leone, S. (Ed.), Synergic Integration of Formal and Informal E-Learning Environments for Adult Lifelong Learners. Hershey (PA, USA): IGI Global. (DOI: 10.4018/978-1-4666-4655-1).

Marín, V.I. (2013). Estrategias metodológicas para el uso de espacios compartidos de conocimiento. In L. Castañeda y J. Adell (Eds.), Entornos personales de aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en Red. (pp. 143-149). Alcoy: Marfil. (http://digitum.um.es/xmlui/bitstream/10201/30419/1/capitulo81.pdf) (10-07-2013).

Marín, V.I., Salinas, J. & de Benito, B. (2012). Using SymbalooEDU as a PLE Or-ganizer in Higher Education. Proceedings of the PLE Conference 2012. Aveiro, Portugal. (http://revistas.ua.pt/index.php/ple/article/view/1427) (10-05-2013).

Marín, V.I., Salinas, J. & de-Benito, B. (2013). Research Results of Two Personal Learning Environments Experiments in a Higher Education Institution. Interactive Learning Environments, (Special Issue: LMS – Evolving from Silos to Structures). (DOI: www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10494820.2013.788031).

Onrubia, J. (1997). Escenarios cooperativos. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 255, 65-70.

Prendes, M.P. (2007). Internet aplicado a la educación: estrategias didácticas y metodologías. In Cabero, J. (Coord.), Nuevas tecnologías aplicadas a la educación (pp. 205-222). Madrid: McGraw-Hill.

Reeves, T.C. (2000). Enhancing the Worth of Instructional Technology Research through «Design Experiments» and Other Development Research Strategies. International Perspectives on Instructional Technology Research for the 21st Century Symposium. New Orleans, LA, USA.

Reeves, T.C. (2006). Design research from the technology perspective. In J. Van-den-Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational Design Research (pp. 86-109). London: Routledge.

Salinas, J. (2012). La investigación ante los desafíos de los escenarios de aprendizaje futuros. Red, 32. (www.um.es/ead/red/32) (07-05-2013).

Salinas, J. (2013). Enseñanza flexible y aprendizaje abierto. Fundamentos clave de los PLEs. In L. Castañeda & J. Adell (Eds.), Entornos personales de aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en Red (pp. 53-70). Alcoy: Marfil. (http://digitum.um.es/jspui/bitstream/10201/30410/1/capitulo3.pdf) (10.7.2013)

Salinas, J., Marín, V.I. & Escandell, C. (in press). Exploring the Possibilities of an Institutional PLE in higher education: Integration of a VLE and an E-Portfolios System. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments.

Salinas, J., Pérez, A. & de Benito, B. (2008). Metodologías centradas en el alumno para el aprendizaje en Red. Madrid: Síntesis.

Sclater, N. (2008). Web 2.0, Personal Learning Environments, and the Future of Learning Management Systems. Educause Center for Applied Research - Research Bulletin, 2008(13). (http://www.educause.edu/library/resources/web-20-personal-learning-environments-and-future-learning-management-systems) (10-05-2013).

Sloep, P. & Berlanga, A. (2011). Redes de aprendizaje, aprendizaje en red. Comunicar, 37, 55-64. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-02-05).

Stahl, G. (2000). A Model of Collaborative Knowledge-Building. In B. Fishman & S. O’Connor-Divelbiss (Eds.), Fourth International Conference of the Learning Sciences (pp. 70-77). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. (http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/-download?doi=10.1.1.97.8816&rep=rep1&type=pdf) (10-05-2013).

Van-den-Akker, J. (1999). Principles and Methods of Development Research. In J. van den Akker, R. M. Branch, K. Gustafson, N. Nieveen & T. Plomp (Eds.), Design Approaches and Tools in Education and Training. (pp. 1-14). Dordretch (The Netherlands): Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wheeler, S. (2009). It’s Personal: Learning Spaces, Learning Webs. Blog entry in Learning with with 'e's. (http://steve-wheeler.blogspot.com.es/2009/10/its-personal-learning-spaces-learning.html) (07-05-2013).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El aprendizaje colaborativo se puede afrontar desde diferentes estrategias. En este artículo contemplamos la creación y mantenimiento de entornos y redes personales de aprendizaje (PLEs y PLNs) y su integración en entornos virtuales institucionales de aprendizaje (EVEA) como estrategias que facilitan y promueven el aprendizaje colaborativo, siempre desde una visión educativa en la que el alumno es autónomo en su propio aprendizaje y trabaja para el logro de metas comunes mediante la realización de actividades de forma conjunta en grupos, existiendo interdependencias positivas. Los objetivos de este trabajo son experimentar con metodologías didácticas de integración del EVEA y los PLEs, y analizar la construcción del PLE por parte de los alumnos universitarios, haciendo especial énfasis en la construcción de la red personal de aprendizaje. Para ello se empleó una metodología de diseño y desarrollo, en una asignatura universitaria de los estudios de maestro de Primaria. Los resultados de la experiencia apuntan a que los alumnos construyen sus PLEs y PLNs en base a sus nuevos conocimientos adquiridos y se produce una adecuada integración metodológica entre esos entornos y el EVEA para el aprendizaje integrado. Como conclusión proponemos un modelo de organización metodológica de integración para el aprendizaje colaborativo a modo de buena práctica.

1. Introducción

La universidad del futuro debe ser una institución que distribuya formación a una gran parte de la población a lo largo de toda su vida y que genere conocimiento al servicio de las necesidades de formación (Salinas, 2012). Esto lleva a configurar diferentes escenarios de aprendizaje que actualmente se empiezan a experimentar e investigar.

Estos escenarios de aprendizaje se están desarrollando en torno al concepto de Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje (PLEs) y entornos de aprendizaje abiertos (Brown, 2010; Hannafin, Land & Oliver, 1999; Sclater, 2008). El concepto de PLE se define, desde una perspectiva pedagógica, como el conjunto de todas las herramientas, materiales y recursos humanos que una persona conoce y utiliza para aprender a lo largo de su vida (Adell & Castañeda, 2010; Attwell, 2007; Hilzensauer & Schaffert, 2008). Las funciones del PLE que tenemos en cuenta en este trabajo, señaladas por Wheeler (2009), son: gestión de la información (relacionada con la gestión personal del conocimiento), creación de contenidos y conexión con otros (lo que se conoce como red personal de aprendizaje o conocimiento). Los PLEs implican un cambio en la educación a favor del aprendizaje centrado en el alumno mediante la superación de las limitaciones de los entornos virtuales de enseñanza-aprendizaje (EVEA) basados en «learning management systems» (LMS). El PLE, por tanto, facilita al alumno tomar el control y gestionar su propio aprendizaje, teniendo en cuenta la decisión de sus propios objetivos de aprendizaje, la gestión de su propio aprendizaje (gestión del contenido y del proceso), la comunicación con otros en el proceso de aprendizaje y todo aquello que contribuye al logro de los objetivos (Salinas, 2013).

Partimos de la teoría conocida como LaaN, del aprendizaje como una red (Learning as a Network), en el cual se integran diferentes conceptos y teorías, como el conectivismo (aprendizaje como conexión), la teoría de la complejidad (comprensión de dinamismo e incerteza del conocimiento en la sociedad actual), el concepto de aprendizaje de doble bucle (aprendizaje de errores e investigación) y, muy especialmente, las ecologías del conocimiento (Chatti, Schroeder & Jarke, 2012; Chatti, 2013), considerando que «aprender es la continua creación de una red personal de conocimiento» (Adell & Castañeda, 2013: 38). Esa Red Personal de Aprendizaje (PLN o PKN) consiste en la suma de conexiones con los PLEs de otras personas (sus herramientas y estrategias de lectura, reflexión y relación), que constituye ecologías de conocimiento (Chatti & al., 2012) y de cuya interacción resulta el desarrollo y facilitación de estrategias para el propio PLE, por lo tanto, son centrales en el aprendizaje y desarrollo profesional (Couros, 2010; Downes, 2010; Sloep & Berlanga, 2011). La idea del PLN es que cada persona contribuye con su conocimiento, por lo que lo más importante no es lo que tiene cada persona en su PLE, sino en el compartir esos recursos. La teoría LaaN es «un intento de elaborar una fundamentación teórica sobre el aprendizaje y la enseñanza cuya puesta en acción sea la construcción y el enriquecimiento del propio PLE» (Adell & Castañeda, 2013: 38).

Asimismo, los PLEs también se pueden utilizar desde presupuestos constructivistas del aprendizaje (Adell & Castañeda, 2013), puesto que pueden cumplir las cinco características de actividades para el aprendizaje significativo propuestas por Jonassen y colaboradores (2003) son activas, constructivas, intencionales, auténticas y colaborativas. En este caso, nos interesa especialmente destacar los PLEs para el desarrollo de actividades colaborativas. Un entorno colaborativo (CSCL, «Computer Supported Collaborative Learning») se basa en el trabajo en grupo desde la interacción y colaboración (Lipponen, 2002), aporta herramientas de comunicación y pone a disposición recursos humanos de diferentes ámbitos (profesores, expertos, compañeros,...). La colaboración como estrategia de aprendizaje, se basa en el trabajo en grupos de personas heterogéneas pero con niveles de conocimiento similares para el logro de metas comunes y la realización de actividades de forma conjunta, existiendo una interdependencia positiva entre ellas (Dillenbourg, 1999; Prendes, 2007). En las actividades colaborativas no existe una única respuesta correcta, sino que hay diversas maneras de llegar al resultado y para ello los alumnos deben compartir y llegar a acuerdos, hecho que les ayuda a ser más autónomos y maduros social e intelectualmente (Bruffee, 1995).

Este estudio se enmarca en un proyecto de investigación más amplio que busca definir y experimentar distintas estrategias didácticas de integración de los PLEs y los EVEA teniendo en cuenta diferentes ámbitos de aprendizaje (formal, no formal e informal), partiendo de trabajos previos (Marín, 2013; Marín & Salinas, en prensa; Marín, Salinas & de Benito, 2012, 2013; Salinas, Marín & Escandell, en prensa).

Retomando estas ideas, en este artículo presentamos una experiencia en la que se ponen en práctica metodologías que buscan fomentar la colaboración y la integración de esos entornos (PLEs y PLNs por un lado, y EVEA por el otro) en el ámbito universitario, junto con algunos de los resultados que se han observado en dicho proceso.

2. Metodología del estudio

El estudio se realizó con un grupo de docentes y alumnos de la asignatura «Medios y recursos tecnológicos para la Educación Primaria», del tercer curso de los estudios de Grado de Maestro de Primaria de la Universidad de las Islas Baleares. La materia tiene una carga de 6 créditos ECTS y pretende desarrollar competencias de utilización de la tecnología para favorecer procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje en la escuela.

El grupo de la asignatura lo conforman tres profesoras y 192 alumnos, organizados en tres grupos grandes de 70 personas aproximadamente y diez grupos prácticos de 25 personas.

Todos los estudiantes tenían previo conocimiento de herramientas tecnológicas puesto que ya habían cursado durante el primer curso otra asignatura relacionada con la tecnología educativa («TICs aplicadas a la Educación Primaria»).

De acuerdo a un cuestionario inicial, respondido por 179 alumnos, se puede extraer que la mayoría son mujeres (71%), tienen menos de 24 años (un 70%) y son usuarios frecuentes de redes sociales (principalmente Facebook), buscadores genéricos (Google) y páginas de visualización de vídeos (Youtube). Esto nos genera un perfil de usuario de Internet básicamente de tipo consumidor: consumen información y se comunican con sus amigos, pero apenas producen contenidos.

El desarrollo de la materia se basó en los principios de aprendizaje centrados en el alumno y metodologías centradas en la colaboración y la construcción social del conocimiento (Salinas, Pérez & de Benito, 2008). Se estructuró en torno a las siguientes actividades, relacionadas con el desarrollo del PLE del alumno, según las funciones básicas indicadas por Wheeler (2009): a) desarrollo de un proyecto de trabajo en grupo basado en el diseño y desarrollo; b) la creación de redes personales de aprendizaje; y c) la utilización de la tecnología de red apropiada para localizar y gestionar información, crear contenidos y compartir conocimiento. Además, se organizó una estrategia metodológica que permitiera integrar la utilización del PLE en el EVEA, en la que el EVEA ofrece el acceso a la documentación básica de la materia y espacios de comunicación en gran grupo o privados y el desarrollo del PLE permite desarrollar procesos de gestión de información y participación en redes de aprendizaje externas. Se describen a continuación los elementos de la estrategia representados en la figura 1, partiendo de las actividades de la asignatura y algunas características del aprendizaje colaborativo.

Actividades relacionadas con la gestión de la información:

• Acceder a las guías de estudio de la materia. Los contenidos se presentan estructurados en mapas conceptuales que representan e interconectan los conceptos básicos y aportan recursos complementarios (lecturas, vídeos, ejemplos, etc.). Se ofrecen indicaciones para el desarrollo del proyecto de trabajo y las actividades prácticas. Estos materiales los proporcionan las profesoras y los disponen en el EVEA, basado en Moodle.

• Localizar, acceder y organizar materiales complementarios mediante el uso de buscadores genéricos (p.e.: Google), marcadores sociales (p.e.: Delicious), buscadores específicos (p.e.: Google Académico), curación de contenidos (p.e.: materiales publicados/compartidos en Twitter por uno mismo u otros). Se anima a los alumnos a localizar información útil para el desarrollo de las actividades del curso y organizar sistemas de organización de la información.

• Organizar y gestionar personalmente la información (mediante herramientas de organización personal, suscripción por RSS a blogs/páginas, seguimiento en Twitter, uso de SymbalooEDU para la organización de nueva información). Asimismo, desde el marco de la asignatura, se ofrece al alumno los recursos y enlaces compartidos (paper.li).

Actividades relacionadas con la generación de contenidos:

• Organizar el propio PLE utilizando SymbalooEDU, en el que cada alumno organiza las herramientas y recursos que utiliza para el desarrollo de las actividades de la asignatura y para otros ámbitos.

• Crear un blog personal que dé cuenta de las actividades de aprendizaje desarrolladas durante el curso. Las entradas incluyen materiales desarrollados por los alumnos en diferentes formatos (texto, audio, vídeo, textos, multimedia interactivos, etc.) y reflexiones sobre las prácticas.

• Desarrollar y publicar un proyecto colaborativo en grupo que requiere la creación de materiales didácticos para la Educación Primaria (multimedia interactivo, vídeo y webquest). Este proyecto sigue las características del aprendizaje colaborativo, según Johnson, Johnson y Holubec (1999): existencia de interdependencia positiva, responsabilidad individual y grupal, interacción estimuladora, disposición de actitudes y habilidades personales y grupales necesarias, y evaluación grupal. La entrega de dicho proyecto se realiza a través del EVEA.

Finalmente, en relación a la conexión con otros, se incluyen las siguientes actividades:

• Interactuar y colaborar con otros a través del EVEA en relación a las actividades propuestas en foros (debates) o a mensajes privados con la profesora o con otros alumnos. Estas actividades se adecúan a las características indicadas por Onrubia (1997) del aprendizaje colaborativo: son tareas grupales, requieren de la contribución de todos y tienen recursos suficientes para llevarla a cabo.

• Compartir y difundir resultados de actividades mediante el blog personal y envío de mensajes en Twitter, a través de los «hashtags» establecidos (conversaciones en Twitter) para la asignatura, a otras personas y/o compañeros para difundir su trabajo en el blog y compartir recursos de interés, fomentando la interacción, participación y comunicación (Ingram & Hathorn, 2004).

• Comunicarse y colaborar en comunidades virtuales y redes sociales docentes o de otros intereses (más allá del «hashtag» de la asignatura en Twitter).

• Ampliar su red personal de aprendizaje (PLN) siguiendo a personas de interés, tanto en Twitter como en otras redes sociales o comunidades virtuales, o por suscripción RSS, con profesores, expertos, personas relacionadas con aficiones...

2.1. Instrumentos de recogida de información

Los instrumentos de recogida de información son tanto cualitativos como cuantitativos, con el objetivo de facilitar la interpretación y complementariedad de la información. Se trata de los siguientes instrumentos:

• Análisis de documentos respecto a la integración de elementos del PLE. Estos documentos son algunas de las producciones que los alumnos han desarrollado durante la asignatura: por un lado, los proyectos grupales y las entradas del blog personal; y por el otro, la evolución en la construcción del PLE, representado gráficamente mediante las capturas de pantalla de sus SymbalooEDU.

• Observación de la acción del alumnado respecto a la implementación de la integración didáctica relacionada con la red personal de aprendizaje. Para ello, se realiza un análisis descriptivo y cuantitativo no exhaustivo de las interacciones realizadas en Twitter. Se tienen en cuenta intervenciones, comentarios entre alumnos, seguimiento de personas internas y externas a la asignatura, interacciones con el objetivo de compartir recursos, actividades, etc. También se revisa una observación descriptiva del dinamismo de los PLN en los blogs.

2.2. Fases del estudio

La experiencia se llevó a cabo según cuatro fases, de acuerdo con la metodología de diseño y desarrollo (Reeves, 2000, 2006; Van-den-Akker, 1999):

• Fase 1. Análisis de la situación y definición del problema. Se revisan investigaciones precedentes en la integración tecnopedagógica de los PLEs y los EVEA. Se define la necesidad de mejorar y optimizar los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje con el objetivo de integrar todos los ámbitos del aprendizaje y centrarse en estrategias que pongan el foco del aprendizaje en el alumno.

• Fase 2. Desarrollo de soluciones. Se diseña, conjuntamente con la profesora responsable de la asignatura, una estrategia metodológica de integración didáctica del PLE y del EVEA, que se ha descrito previamente. Se trabaja con las profesoras en los elementos de la estrategia menos conocidos para ellas.

• Fase 3. Implementación y evaluación. En esta fase se pone en práctica en la asignatura la estrategia diseñada, al mismo tiempo que se hace seguimiento del proceso y se introducen adaptaciones de mejora iterativa en la estrategia (p.e.: dificultades técnicas en el uso de paper.li y Twitter hicieron plantear el uso de otras herramientas). Al inicio de la asignatura se realiza el taller de PLE con los alumnos y se les pide que pongan en sus blogs al inicio y al final de la asignatura sus capturas de pantalla de SymbalooEDU, que representarían su PLE. Periódicamente se recogen las entradas de los blogs personales y se guardan las capturas de pantalla de SymbalooEDU en los blogs, a partir del seguimiento de RSS. De las capturas se realiza un análisis de contenido mediante el recuento de los bloques introducidos y según su tipología de acuerdo con las tres funciones del PLE. De los proyectos grupales, recogidos en el EVEA, y las entradas de los blogs se hace una un análisis descriptivo sobre la selección e integración de herramientas.

Por otro lado, también se recogen los tweets realizados con los «hashtags» de la asignatura diariamente a través de un sistema automático de recogida de tweets (Rowfeeder). Después se realiza un análisis de contenido mediante el recuento de tweets y se codifican de acuerdo a su tipo. Posteriormente se examinan las interacciones en el blog de las personas identificadas como más activas en Twitter, revisando los comentarios en sus blogs.

• Fase 4. Producción de documentación y principios de diseño. La evaluación de la estrategia a través de los datos recogidos lleva a la propuesta de un modelo de integración didáctica del PLE del alumno y el EVEA.

3. Resultados

3.1. Construcción del PLE

Respecto a la evolución en el PLE de los alumnos, en la siguiente tabla se indican las estadísticas importantes a tener en cuenta sobre las capturas de SymbalooEDU y el grado de participación al inicio y final de la asignatura, como se observa en la tabla.

La imagen resultante de este recuento nos da una idea del tipo de herramientas que los alumnos utilizaban al principio y al final de la asignatura en su PLE, ya fuera porque las utilizan o porque las consideran interesantes para utilizar en el presente o en un futuro más o menos próximo.

Se puede observar en la tabla la evolución en los porcentajes de cantidad de bloques por tipo de recursos.

A pesar de que la evolución en la cantidad de bloques por tipo de herramienta no experimenta grandes cambios (el más significativo es el aumento del 20% al 28% en bloques referidos a herramientas de generación de contenidos), sí se nota un importante incremento en el número de recursos incluidos al principio (101) y al final (144), teniendo en cuenta las diferentes tipologías.

Como estadísticas más específicas, entrando en cada tipología, se pueden observar notables diferencias entre las herramientas y enlaces utilizados al inicio y al final de la asignatura, a pesar de que hay algunos que se mantienen.

En relación a los recursos de gestión de la información, destaca el uso de herramientas relacionadas con la localización de información relevante para el desarrollo del proyecto del curso como enlaces de noticias (muchas de ellas relacionadas con la aplicación de las tecnologías en la educación), de repositorios de aprendizaje (p.e., actividades educativas) y buscadores. Observamos el aumento en los dos primeros. Entre las páginas de inicio, y como herramientas de organización personal, algunos alumnos incluyeron SymbalooEDU. Este dato es interesante pues la organización y gestión de la información es uno de los objetivos del PLE.

El mayor incremento se observa en las herramientas de generación de contenidos. Puesto que la asignatura trabajaba principalmente la generación de contenidos educativos para la Educación Primaria, muchos de los alumnos han incluido en sus PLEs aplicaciones que consideran útiles para ese propósito. Entre los bloques incluidos destacan las herramientas de creación colaborativa, de creación de ejercicios interactivos, los blogs, la creación de webs, audio, creación de imágenes, murales, cómics y vídeos. Se puede observar una gran variedad de herramientas dentro de cada categoría, aunque las más frecuentes son unas pocas.

Al inicio de la asignatura, las herramientas de generación de contenidos más recurrentes resultan ser los blogs (Blogger) y las herramientas de trabajo colaborativo (Google Drive). Al final de la asignatura, siguen siendo recurrentes esas herramientas, pues se siguen utilizando durante el curso y les resultan de utilidad, pero además se evidencia un incremento de otras herramientas de generación de contenidos, como se ha indicado anteriormente.

Finalmente, en relación a la comunicación con otros, destacan las redes sociales y las herramientas de comunicación asíncrona. Se observa un incremento en las herramientas requeridas para compartir las actividades de la asignatura a través del blog (por ejemplo: herramientas para compartir archivos, vídeos, presentaciones visuales, documentos de texto...). También se observa en la categoría de redes sociales genéricas, respecto al inicio, la inclusión más mayoritaria de Twitter en los PLEs de los alumnos.

3.2. Desarrollo del PLN

Respecto al desarrollo de la red personal de aprendizaje, se tuvo en cuenta principalmente el uso de Twitter por parte de los alumnos. Se contaron un total de 1.986 tweets utilizando los «hashtags» establecidos para ello, sin tener en cuenta los que estaban repetidos. En total participaron 189 de los alumnos entre los tres grupos, 47 de los cuales ya disponían previamente de una cuenta en esta red social.

La media de tweets por persona se sitúa en 10,51 (el mínimo ha sido 1 y el máximo 112), la moda es de 10 y la densidad es baja (0,11), pues la mayor parte de las interacciones proceden de pocos autores. Éstos son los que se han configurado como «líderes de cada grupo». Es importante esta figura pues actúa de dinamizador del grupo en la red social y anima a la participación de otros compañeros. Se dividieron los 1.986 tweets en función del uso dado. A continuación se pueden observar los resultados:

• 1.451 tweets (73%) fueron dedicados a compartir los resultados de las actividades de la asignatura con el resto de compañeros, tal como estaba indicado en las instrucciones iniciales de la asignatura.

• 190 tweets (10%) consistieron en compartir recursos de interés para el resto del grupo de la asignatura. Estos contenidos estaban relacionados con los que se estaban trabajando en clase. En 37 de estos 190 tweets se produjo una interacción con personas externas a la asignatura (profesores, organizaciones educativas,...), mediante retweets o menciones.

• 182 tweets (9%) eran de comunicación «informal», entendiendo esta como mensajes a todo el grupo (saludos), comentarios o diálogos con otros compañeros sobre la asignatura (petición de ayuda, preguntas...).

• 163 tweets (8%) se registraron en relación a interacciones entre alumnos: retweets de compañeros o menciones relacionadas con la elaboración conjunta de entradas del blog, el proyecto grupal, etc.

Por otro lado, se revisaron el número de seguidores y seguidos. Así, la media de seguidores por alumno resultó ser de 38,38 y de seguidos 61,39. En cuanto a los seguidos, de los 189 alumnos que participaron en Twitter con el «hashtag» de su grupo en la asignatura, 82 comenzaron a seguir a personas/organizaciones externas a la asignatura. Por lo tanto, en muchos casos los alumnos enriquecieron el uso de la red social yendo más allá del ámbito formal, especialmente incluyendo el informal.

Partiendo del porcentaje de participación no obligatoria (interacciones no dirigidas a compartir el blog) media : 2,83), se tuvieron en cuenta las personas que tenían una participación superior a cinco tweets. Se descartaron aquellos que superaban ese número por realizar interacciones del tipo mención por trabajo conjunto en entradas de blog (tweets no orientados a la dinamización del espacio social). De esta manera, se contaron un total de 13 personas, nueve alumnos del primer grupo, dos en el segundo grupo y uno en el tercer grupo.

Asimismo, la dinámica de cada grupo en Twitter fue diferente. Las personas activas del primer grupo, y con menos notoriedad en el tercer grupo, se orientaban a compartir recursos y comentarlos, mientras que en el segundo grupo se trató más de un espacio de ayuda informal. En este caso se observó que el PLN de los alumnos se creó en torno a los blogs, pues uno de ellos actuaba de mentor y los demás lo seguían y se apoyaban en sus explicaciones. Por otro lado, no se observan interacciones significativas entre grupos.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

A lo largo de la asignatura el EVEA ha sido un puente entre el PLE del alumno y la institución educativa. Se ha utilizado sobre todo como portal inicial aunque prácticamente todo el proceso de aprendizaje se ha desarrollado a través de elementos externos que componían o han llegado a formar parte del PLE del alumno (blogs, Twitter...). Asimismo, el EVEA se integra didácticamente de forma natural en el PLE de los alumnos.

Por otro lado, se constata también la evolución en la construcción del PLE y el PLN por parte de los alumnos. Se han desarrollado procedimientos basados en la localización y gestión de información útil para resolver problemas, la creación de contenidos y la comunicación con los otros. En este proceso han utilizado herramientas conocidas y seleccionado nuevas de forma continua; han integrado herramientas utilizadas en otros ámbitos y extrapolado a otros contextos los espacios creados en el marco de la asignatura.

En esta evolución en la gestión del propio proceso de aprendizaje, los alumnos han experimentado el paso de ser consumidores pasivos de información y recursos a ser también creadores de contenidos y materiales en variedad de formatos (Hilzensauer & Schaffert, 2008). Esta variedad responde a la estrategia metodológica de la asignatura que promueve la creación de contenidos al tiempo que deja autonomía para que sea el alumno –o grupo– quien seleccione las herramientas más adecuadas a las necesidades de la actividad y a sus características.

Además, se han puesto las bases para la creación de redes personales de aprendizaje en tanto que los alumnos han aprendido a participar de la red social, organizar una red social de aprendizaje, y a participar de una cultura del compartir. Sin embargo, todavía es necesario superar algunos retos como el nivel de participación y el grado de implicación para el desarrollo de un verdadero proceso colaborativo a partir de la interacción y comunicación (Kirschner, 2002). Se observan diferentes tipos de redes pero circunscritas al grupo en la asignatura con interacciones externas ocasionales y basadas en el apoyo, la distribución de recursos filtrados y la redistribución de intervenciones tanto propias como de otros.

El impacto de la experiencia en los aprendizajes de los alumnos derivado de la implementación de la estrategia se valora como positivo pues promueve la autonomía del alumno en su aprendizaje, así como la construcción colaborativa de conocimiento a partir del desarrollo del proyecto grupal y las redes construidas en torno a la asignatura. Estas redes de aprendizaje representan un gran potencial que debe ser valorado como estrategia para el cambio metodológico hacia formas de aprendizaje significativas, basadas en la solución de problemas o el desarrollo de proyectos.

Esta experiencia ha permitido desarrollar y valorar procesos de construcción social del conocimiento, promoviendo que el alumno: a) busque información, identifique problemas, adquiera criterios para filtrar, interconectar y localizar datos relevantes y distribuya información útil; b) reconozca y exprese su visión personal (ideas y avances) y c) la comparta con el grupo y sea capaz de diferenciar su mirada, adoptar nuevas perspectivas, clarificar puntos de desacuerdo, argumentar, negociar acuerdos (Bruffee, 1995) y en última instancia formular y representar conocimientos (Stahl, 2000). Por ello, proponemos un modelo de organización metodológica como buena práctica para el aprendizaje colaborativo, con propuesta de herramienta en paréntesis para cada elemento, tal como se ve en el gráfico.

El PLE como elemento central incluye los espacios y procesos marcados por sus funciones (Wheeler, 2009): de creación de contenidos, tanto individuales (e-portfolio, selección de herramientas) como grupales (con herramientas de trabajo colaborativo y de comunicación), de gestión de información (selección y recomendación de recursos individual y colaborativamente) y de conexión con otros (a través de un espacio abierto de comunicación social y colaboración para la creación de comunidades de aprendizaje de construcción colaborativa de conocimiento).

Se incluyen, respecto al modelo inicial, los cambios de herramientas propuestas en relación a dificultades técnicas con Twitter y paper.li: introducción de sistemas de agregación de contenidos (Scoop.it, Twubs) para una mejor gestión de la información y del PLN, y las herramientas objeto de esta asignatura (generación de materiales didácticos para Educación Primaria).

Apoyos

Este artículo forma parte de la ejecución del proyecto I+D EDU2011-25499 «Estrategias metodológicas para la integración de entornos virtuales institucionales, sociales y personales de aprendizaje», subvencionado por el Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, en el Programa Nacional de Investigación Fundamental a iniciar en el 2012, que lleva a cabo el Grupo de Tecnología Educativa de la Universidad de las Islas Baleares.

Referencias

Adell, J. & Castañeda, L. (2010). Los Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje (PLEs): una nueva manera de entender el aprendizaje. In R. Roig Vila & M. Fiorucci (Eds.), Claves para la investigación en innovación y calidad educativas. La integración de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación y la Interculturalidad en las aulas. Stumenti di ricerca per l’innovaziones e la qualità in ámbito educativo. La tecnologie dell’informazione e della comunicazione e l’interculturalità nella scuola (pp. 19-30). Alcoy: Marfil / Roma TRE Università degli Studi. (http://hdl.handle.net/10201/17247) (10-05-2013).

Adell, J. & Castañeda, L. (2013). El ecosistema pedagógico de los PLEs. In L. Casta-ñeda & J. Adell (Eds.), Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en red (pp. 29-51). Alcoy: Marfil. (http://digitum.um.es/xmlui/bitstream/10201/30409/1/capitulo2.pdf) (10-07-2013).

Attwell, G. (2007). Personal learning environments - the future of eLearning? In eLearning Papers, 2(1), 1-8. (www.elearningeuropa.info/files/media/media11561.pdf) (10-05-2013).

Brown, S. (2010). From VLEs to learning webs: the implications of Web 2.0 for learning and teaching. Interactive Learning Environments, 18(1), 1-10. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10494820802158983).

Bruffee, K. (1995). Sharing our toys - Cooperative learning versus collaborative learning. Revista Change, 27(1), 12-18. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1995.9937722)

Chatti, M.A. (2013). The LaaN Theory. In S. Downes, G. Siemens y R. Kop (Eds.), Personal learning environments, networks, and knowledge. (www.elearn.rwth-aachen.de/dl1151|Mohamed_Chatti_LaaN_preprint.pdf) (07-05-2013).

Chatti, M.A., Schroeder, U. & Jarke, M. (2012). LaaN: Convergence of Knowledge Management and Technology-enhanced Learning. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 5(2), 177-189. (DOI: http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/TLT.2011.33).

Couros, A. (2010). Developing Personal Learning Networks for Open and Social Learning. In G. Veletsianos (Ed.), Emerging Technologies in Distance Education. (pp. 109–128). Canada: AU Press, Athabasca University.

Dillenbourg, P. (1999). Collaborative Learning Cognitive and computational Ap-proaches Advances in learning and instructional series. Oxford (UK): Pierre Per-gamon.

Downes, S. (2010). Learning Networks and Connective Knowledge. Collective Intelli-gence and ELearning 20 Implications of Web Based Communities and Networking (pp. 1-26). IGI Publishing. (http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-729-4.ch001).

Hannafin, M.J. Land, S. & Oliver, K. (1999). Open Learning Environments: Founda-tions, Methods and Models. In C.M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-Design Theories and Models. A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory. (Volume II, pp. 115–140). Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Hilzensauer, W. & Schaffert, S. (2008). On the way towards Personal Learning Environments: Seven crucial aspects. In Elearning Papers, 9. (www.elearningeuropa.info/files/media/media15971.pdf) (10-05-2013).

Ingram, A. & Hathorn L. (2004). Methods for analyzing collaboration in online communications. In T. Roberts (Ed), Online Collaborative Learning: Theory and Practice (pp. 215-241). Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing. (http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59140-174-2.ch010).

Johnson, D. & Johnson, R. (1996). Cooperation and the Use of Technology. In M.J. Spector, D.M. Merrill, J. Van-Merrienboer & M.P. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (vol. 1, pp. 785-812). New York: Routledge.

Johnson, D., Johnson, J. & Holubec, E. (1999). El aprendizaje cooperativo en el aula. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Jonassen, D.H., Howland, J.L., Moore, J.L. & Marra, R.M. (2003). Learning to Solve Problems with Technology: A Constructivist Perspective. Upper Saddle River (New Jersey): Merrill Prentice Hall.

Kirschner, P.A. (2002). Can we support CSCL? Educational, Social and Technological Affordances for Learning. In P.A. Kirschner (Ed.), Three Worlds of CSCL: Can We Support CSCL? (pp. 7-47). Heerlen (The Netherlands): Open University of the Netherlands. (http://hdl.handle.net/1820/1618) (17-08-2013).

Lipponen, L. (2002), Exploring Foundations for Computer-supported Collaborative Learning, CSCL '02 Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Support for Collaborative Learning: Foundations for a CSCL Community, pp. 72-81, (http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1658627) (17-08-2013).

Marín, V.I. & Salinas, J. (in press). First Steps in the Development of a Model for Integrating Formal and Informal Learning in Virtual Environments. In Leone, S. (Ed.), Synergic Integration of Formal and Informal E-Learning Environments for Adult Lifelong Learners. Hershey (PA, USA): IGI Global. (DOI: 10.4018/978-1-4666-4655-1).

Marín, V.I. (2013). Estrategias metodológicas para el uso de espacios compartidos de conocimiento. In L. Castañeda y J. Adell (Eds.), Entornos personales de aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en Red. (pp. 143-149). Alcoy: Marfil. (http://digitum.um.es/xmlui/bitstream/10201/30419/1/capitulo81.pdf) (10-07-2013).

Marín, V.I., Salinas, J. & de Benito, B. (2012). Using SymbalooEDU as a PLE Or-ganizer in Higher Education. Proceedings of the PLE Conference 2012. Aveiro, Portugal. (http://revistas.ua.pt/index.php/ple/article/view/1427) (10-05-2013).

Marín, V.I., Salinas, J. & de-Benito, B. (2013). Research Results of Two Personal Learning Environments Experiments in a Higher Education Institution. Interactive Learning Environments, (Special Issue: LMS – Evolving from Silos to Structures). (DOI: www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10494820.2013.788031).

Onrubia, J. (1997). Escenarios cooperativos. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 255, 65-70.

Prendes, M.P. (2007). Internet aplicado a la educación: estrategias didácticas y metodologías. In Cabero, J. (Coord.), Nuevas tecnologías aplicadas a la educación (pp. 205-222). Madrid: McGraw-Hill.

Reeves, T.C. (2000). Enhancing the Worth of Instructional Technology Research through «Design Experiments» and Other Development Research Strategies. International Perspectives on Instructional Technology Research for the 21st Century Symposium. New Orleans, LA, USA.

Reeves, T.C. (2006). Design research from the technology perspective. In J. Van-den-Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational Design Research (pp. 86-109). London: Routledge.

Salinas, J. (2012). La investigación ante los desafíos de los escenarios de aprendizaje futuros. Red, 32. (www.um.es/ead/red/32) (07-05-2013).

Salinas, J. (2013). Enseñanza flexible y aprendizaje abierto. Fundamentos clave de los PLEs. In L. Castañeda & J. Adell (Eds.), Entornos personales de aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en Red (pp. 53-70). Alcoy: Marfil. (http://digitum.um.es/jspui/bitstream/10201/30410/1/capitulo3.pdf) (10.7.2013)

Salinas, J., Marín, V.I. & Escandell, C. (in press). Exploring the Possibilities of an Institutional PLE in higher education: Integration of a VLE and an E-Portfolios System. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments.

Salinas, J., Pérez, A. & de Benito, B. (2008). Metodologías centradas en el alumno para el aprendizaje en Red. Madrid: Síntesis.

Sclater, N. (2008). Web 2.0, Personal Learning Environments, and the Future of Learning Management Systems. Educause Center for Applied Research - Research Bulletin, 2008(13). (http://www.educause.edu/library/resources/web-20-personal-learning-environments-and-future-learning-management-systems) (10-05-2013).

Sloep, P. & Berlanga, A. (2011). Redes de aprendizaje, aprendizaje en red. Comunicar, 37, 55-64. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-02-05).

Stahl, G. (2000). A Model of Collaborative Knowledge-Building. In B. Fishman & S. O’Connor-Divelbiss (Eds.), Fourth International Conference of the Learning Sciences (pp. 70-77). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. (http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/-download?doi=10.1.1.97.8816&rep=rep1&type=pdf) (10-05-2013).

Van-den-Akker, J. (1999). Principles and Methods of Development Research. In J. van den Akker, R. M. Branch, K. Gustafson, N. Nieveen & T. Plomp (Eds.), Design Approaches and Tools in Education and Training. (pp. 1-14). Dordretch (The Netherlands): Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wheeler, S. (2009). It’s Personal: Learning Spaces, Learning Webs. Blog entry in Learning with with 'e's. (http://steve-wheeler.blogspot.com.es/2009/10/its-personal-learning-spaces-learning.html) (07-05-2013).

Document information

Published on 31/12/13

Accepted on 31/12/13

Submitted on 31/12/13

Volume 22, Issue 1, 2014

DOI: 10.3916/C42-2014-03

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?