(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== The a...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 807240276 to Milojevic et al 2013a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 13:36, 29 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to map out the research around the concept of interactivity, as well as to point out the dominant streams and underresearched areas. It is based upon the content analysis of methods employed in articles published in five topranking communication journals over five year period (200610). The review of methods applied in research of interactivity is based upon distinction between social interactivity, textual interactivity and technical interactivity. This classification is further developed by adding the category of levels of interactivity (low, medium and high) which allows further classification of different mediated practices. This leads to specification of nine theoretical subsets of interactivity as the main categories of the analysis of research articles. Within this matrix we have situated diverse methods that respond to conceptually different types and levels of audience/users interactivity. The analysis shows that scholarly focus lies within the low textual and the high social interactive practices, whereas the high technical and high textual interactivity are underresearched areas. Investigations into the audience/users relations with texts are mainly orientated towards content analyses and surveys. High social interaction research is reviving the application of ethnographic methods, while the possibilities of technical interactivity are embraced not as an object but as a tool for research.

1. Introduction

The advancement of communication technologies brought about new modes of communication in the public domain, new paths and fluxes of messages’ intersections, transforming the linear model into what Gunter (2003) summed up as a one-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-many and many-to-one model of public communication. The transformation of communication technologies «empowered» the previously passive audience with tools to alter/collaborate in creator content, involve/pace social interaction with the author/audience and to take part in the technological or architectural structure of media by producing new/ unlocking present digital codes. Interactivity, although a highly contested concept in media and audience studies, becomes rather useful for interrogating the roughly sketched transformation of the communication social system and of the audience as its inherent part.

This article will view interactivity as differentia specifica that exceeds and encompasses changes that shape the new media ecology. Its aim is to map out the research around the concept of interactivity, to point out the dominant streams and under-researched areas and to situate diverse methods that respond to conceptually different types and levels of interactive practices.

2. Concept of Interactivity

The starting obstacle in investigating interactivity is the problem of circumscribing and operationally defining the concept. Although it has been in focus for almost three decades now, even the recent scholarly examination of interactivity starts with concept explanation (Sohn, 2011; Koolstra & Bos, 2009; Rafaeli & Ariel, 2007; McMillan, 2002; Kiousis, 2002). A review of previous research shows that the obstacles can be placed in three groups:

First, the concept is theorized and used in a multitude of disciplines ranging from computer science, information science, advertising and marketing to media studies. Therefore it is defined from numerous perspectives.

Second, there is a difference between feature-based versus perception-based interactivity. Different authors defined interactivity either as a structural element of the medium (Manovich, 2001), or as a perception variable in the mind of the user (Wise, Hamman & Thorson, 2006). In the context of this article we will avoid this dispute by arguing that actual interactivity cannot be strictly contrasted to perceived interactivity as a psychological state experienced by the user. Or as Rafaeli and Sudweeks (1997, cited in Cover, 2006: 141) state, interactivity is not a characteristic of the medium, but a process-related construct about communication.

The third is the dimensional character of interactivity. The multidimensionality of the concept was variously determined by interrelations between: frequency, range, and significance; direction of communication, user control, and time; speed, range, and facilitating users’ manipulation of contents; or by degree of sequential relatedness among messages (Jensen, 1999).

Szuprowicz (1995) introduces a more unified approach and identifies three dimensions of interactivity: user-to-user, user-to-documents, and user-to-computer (user-to-system). This approach can be a good starting point for further exploration of the interactivity because it examines audience relations with three crucial components of every mediated communication – content, other participants and technology. Furthermore, the conceptualization of interactivity through these three dimensions leads to a framework that is inclusive of many different perspectives and approaches, and provides a rather large umbrella needed for this research. Having that in mind, we take up the presented dimensional treatment of interactivity which we will label:

• Social interactivity (interaction among users).

• Textual interactivity (interaction between user and documents).

• Technical interactivity (interaction between user and system).

Another contested issue in the media theory and research is the degree or level of interactivity. Essentially, there is a question of how much interaction with other users, texts and systems can be achieved. First Kayany, Wotring and Forrest (1996) and later McMillan (2002) suggest that users exert relational (or interpersonal), content (or document-based) and process/sequence (or interface-based) type of control. Although in McMillan’s framework the level of control is not the only dimension of interactivity, it is the only one relevant to all types of interaction.

In line with these arguments, we propose that interactivity, defined as control over text, social interaction and medium, can be subdivided into three levels: low, medium and high, defined by the control users are able to exert. This means that within each type of control, different degrees can be identified and analysed.

If we think about interactivity as a continuum of different practices, the activity of the audience as recipients in classical mass communication flow would be at the lower end, while actions similar to those of producer or participant in interpersonal communication would be at the opposite, high side. In some practices, the audience does not have the possibility to control any of the three dimensions of interactivity. For example, they cannot initiate communication, alter text, or influence other participants in communication. We argue that this is not a situation of zero control because even in the typical mass communication situation, audience members can stop the communication or interpretatively control media texts. These low levels of interaction are seeds of what will grow into higher levels of audience control (Cover, 2006).

The medium level of interactivity refers to the activities in which the audience exercises control, but within pre-given parameters and rules. In terms of social interactivity, this means that authors have envisaged and provided channels for users to respond and maintain interaction. The textual medium interactivity is typically related to those situations in which users are invited to actively participate in the construction of media content. In the case of technical interactivity, medium control should be seen as producer provided opportunity to participate in the co-construction of some parts of media architecture. The high level of interactivity assumes freedom achieved by the users themselves, contrary to the desired level of control which the producer-creators want to keep.

The intersection of the outlined dimensions of interactivity with the additional levels of control (Table 1) assembles the theoretical model of interactivity which will be used in this article to investigate trends and methods employed in communication research.

3. Method

The selection of the communication journals for any study is faced with one general and one subject specific problem. The general problem is related to the controversy around journal evaluation, in scientometrics and academic circles. After decades of prevalence of the journal impact factor (JIF) applied to the journals from the Web of Science data base, in the last ten years new methods have started to emerge (e.g. h-factor (Braun & al., 2006), EigenfactorTM (www.eigenfactor.org), Article-Count Impact Factor (Markpin & al., 2008) and others. However, there is no agreement on the common method as all of them favour some and neglect other journal characteristics (Bollen & al., 2009). Aware of its limitations, we still opted for JIF as the criteria for inclusion as it is most commonly used in the analysis of communication journals (Feely, 2005) and because it is widely used by promotion and grant review committees (Kurmis, 2003). Journals with higher JIF will be more frequently read, used and cited and, as such, they set trends in research.

Journal Citation Report (JCR) of the Web of Science, the last report available at the time of research, included 55 journals in the Communication field for 2009. The subject specific problem with this list is that it reflects diversity of intellectual traditions and atomization of research domains within the communication scholarship. In order to capture a wider array of interests in the field we have selected the journals which, according to Park and Leydesdorff (2009), fall into the «sector of communication research». Among the first ten highest ranking journals (based on their JIF), those were Journal of Communication (IF 2.415, ranking: 2/55), Human Communication Research (IF 2.200, ranking: 3/55), Communication Research (IF 1.354, ranking: 8/55) and New Media and Society (IF 1.326, ranking: 10/54). General psychology and health-related psychology, as two other primary sectors among communication journals (Park & Leydesdorff, 2009: 169), were excluded. An exception from this criterion was made with the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (IF 3.639, ranking: 1/55) because it was first on the JCR for 2009, it is published by the biggest communication research association ICA, and, most importantly, because its thematic scope promised research in computer-mediated interactive forms. To achieve a representative sample for analysis of trends and methods we analysed papers published during a five-year period, between 2006 and 2010.

In selecting the sample of articles, standard bibliometric research through key words proved insufficient, as in some papers interactivity was not explicitly mentioned, although some aspects were investigated. We included papers which took interactivity into account as an element of the communication process, with or without explication of the term. Second, we were interested in the articles presenting empirical research, because the aim of this paper is to provide insights into methods employed for different types and levels of interactivity. The third criterion was that the object of analysis is public or semi-public communication. In line with the proposed typology, we decided to preserve the minimum condition of «audiencehood», although acknowledging the change indicated by the new terms such as consumers and users. Using these criteria, 98 articles were selected for further analysis

We analysed the content of selected papers using NVivo9 as a software tool. Dependent variables of the code were types of interactivity (social, textual, technical) and levels of interactivity (low, medium, high). Coding was done by the authors. To develop precise definition of variables and resolve dilemmas authors thoroughly discussed 10 articles that were included in inter-coder reliability sample. Additional 40 papers were subject to inter-coder reliability testing. The discrepancies were resolved by simple majority rule (2 of 3) and these 50 papers became part of the full sample. Since inter-coder reliability, calculated using average pairwise per cent, was 0.93 (Table 2), the remaining 48 articles were coded independently.

For the frequency of methods employed in empirical research we adopted a slightly different approach. Using NVivo software we coded information on the methods as they appeared in the articles. Since this information is explicitly provided, the nodes and sub-nodes for each method were added as it appeared in an article.

4. Findings

Within 98 analysed articles, the majority of papers are published in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, New Media and Society and Communication Research (table 3). No significant trend can be traced when it comes to research interest into different types and levels of interactivity, at least not in the five year period (table 3). However, our sample shows that there is a constant interest into interactivity in general, since the article distribution per year varies only 6%, from the lowest 17% in 2006 to the highest 23% in 2007.

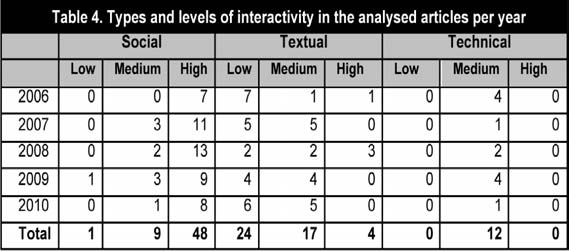

Authors are interested in the low textual and the high social interactivity, while it can be observed that technical interactivity is an under-researched area (Table 4). There are only two articles in which all types of interactivity are accounted for. In terms of methods, they present survey based research interested in general usage of the features of web communication. There are further 12 articles in which two types of interactivity are considered as important, and in majority of them (10 out of 12) it is a combination of social high and technical medium interactivity.

The table 5 shows distribution of methods of research within the matrix of the types and levels of interactivity. In the next section we will discuss it further.

4.1. Textual interactivity

Classified under the subset of low textual interactivity are the papers in which researchers focus on text rather than audience activities. Activities with hypertext and multi-narratives are considered as medium interactivity, while co-creation of the content is regarded as a highly interactive act. The researchers follow the dominant stream of communication research looking at content without audience involvement (table 4).

4.1.1. Low textual interactivity

Media effects paradigm is a dominant theoretical framework in dealing with the low textual interactivity practices. Researchers are interested in: a) the effects of a particular type of media content (e.g. cosmetics surgery makeover program, entertainment TV organ donation stories) on audience behaviour; and b) the impact of certain textual features (sources, narrative types, presentation, characters’ gender) on the audience. The new media audiences are treated in low textual interaction, leaving aside the possibilities offered by the digital medium. For example, even computer games are researched as any other type of media content, without any acknowledgement of user role in creating narration or adjusting the settings (Ivory & Kalyanaraman, 2007; Williams, 2006).

Audience behaviour was also approached from the uses and gratifications perspective in order to research the particular aspects of media use, such as gratification in watching movies (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010), motives for participation in phantasy sport competitions (Farquhar & Meeds, 2007), or patterns of the use of a web site (Yaros, 2006).

Two methods dominate the research into the low textual interactivity – survey and experiment. While survey is used to gain knowledge about television and new media audiences-users, the experimental design is almost exclusively applied in order to investigate the internet and gaming behaviour. The results indicate that in computer-mediated communication, novel ways to manipulate text in order to examine effects of messages emerge. This manipulation allows researchers to control textual features and examine audience responses with higher precision and certainty (Yaros, 2006; Knobloch-Westerwick & Hastall, 2006).

Qualitative research was rarely conducted and it is an exception from the dominant pattern. For example, Buse (2009) finds it the most appropriate for investigating how computer technologies relate to experiences of work and leisure in retirement, while Kaigo and Watanabe (2007) qualitatively analyse reaction to video files depicting socially harmful images in a Japanese internet forum.

4.1.2. Medium textual interactivity

Research into the medium textual interactivity is targeting new media, dominantly web sites and online forums, with two exceptions focusing on computer games. The audience activities that were attracting interests were information seeking, especially related to health issues (Ley, 2007; Balka & al., 2010), and hypertext reading.

Tracking user behaviour through web behaviour recording programs is the frequently used gathering technique in researching medium textual interactivity. Tracking is organized either in the natural setting of the users (Kim, 2009) or, more often, in laboratory controlled and generated conditions (e.g. Murphy, 2006; Tremayne, 2008). To provide additional information about the meaning of computer collected data, researchers need insight into the motives and intentions of participants. Surveys are often used for that purpose (Wu & al., 2010; Wirth & al., 2007; Kim, 2009), but talk aloud protocols or measurement of physiological responses in an experimental setting (Weber & al., 2009) are sometimes used instead.

There are also already established methods that were harder to achieve in previous media environments, such as gathering written narratives from the audience, by e-mails, forums and blogs. Also, content analysis is used to get insight into participants’ selections and navigations while using a search engine (Wirth & al., 2007) or into gamers’ behaviour (Weber & al., 2009).

4.1.3. High textual interactivity

With only four articles, it seems that collaborative content creation is rarely within the range of researchers’ interests. Two types of Wiki content are explored – Wikinews (Thorsen, 2008) and Wikipedia (Pfeil & al., 2006), both based on a content analysis of collaborative products, but not on the processes through which the content is co-created. Cheshire and Antin (2008) used the internet field experiment in order to research the correlation between the feedbacks that an author receives and her/his willingness to post again. Citizens’ readiness to incorporate their own content into local online newspapers was explored using online survey (Chung, 2008).

4.2. Social interactivity

For a long period of time social interactions were researched mostly from the perspective of sociology and psychology interested in unmediated interpersonal communication. Nowadays, this is a relevant topic for media studies, as new technologies enable interpersonal encounters in mediated settings. The boost of forums, social networks and similar social platforms caused significant interest among scientists and our findings confirm that. The majority of articles refer to the different aspect of practices that are labelled as high interactivity because they are the most similar to face-to-face communication which is the prototype of the highest possible interaction. The number of articles that belong to the category of medium social interactivity is more than five times smaller (see Table 3). Para-social interaction with the ‘author ’defined as the low social interactivity, is missing from the research. This is understandable because in the new media environment there is real, sometimes even high, social interaction with the typically distant communicators (celebrities, journalists etc.).

4.2.1. Medium social interactivity

Medium social interactivity is present when audiences have the opportunity to communicate with the authors of media content by sending comments or taking part in live programs, thus having partial control over the interaction. The shift from typical mass media audience to blog audience is evident and logical, because the medium social interaction is embedded in the definition of the blog. The behavioural patterns and attitudes of blog users were researched using online surveys (Sweetser & Kaid, 2008; Kelleher, 2009). The use of online journal style web log was an object of a case study, which included long term participant observation and in depth interviews (Hodkinson, 2007).

Content analysis of comments on blogs, news sites or YouTube is rather vivid in this area of research, so text is used as an indicator for the medium level of social interaction (Robinson, 2009; Antony & Thomas, 2010). Compared to the traditional content analysis, the scope of the mentioned studies has increased significantly. For example, employing semi-automatic methods to detect frequency of certain words during crisis, Thelwall & Stuart (2007) used evidence from postings blogs and news feeds. Online posts were also used to assess the salience of different opinion frames with that of different media frames, as in agenda-setting research (Zhou & Moy, 2007).

Similar to manipulation of texts, there are social experiments in creating blogs and observing participants behaviour. For example, Cho & Lee (2008) have created discussion board for students from three distant universities and analysed posting frequency in relation to socio-cultural factors.

4.2.2. High social interactivity

Social interactions through different online social networks, or rather high social interactivity, prove to be the richest field of investigation in communication journals. Two main methods of research are employed, depending on the authors’ orientation towards either control (experiment) or naturalism (ethnography). Experimental design is usually followed by surveys, and ethnography by in-depth interviews. Field experiment emerges as a method designed to include elements of both.

Ethnographic tradition has flourished in the past twenty years, partly due to the emergence of numerous online communities. In the articles analysed, virtual ethnography methods range from observing online communities to exploring their connections with everyday life. By engaging in online mothering group, Ley (2007) studied the significance of the site architecture for members’ commitment to their online support groups, while Campbell (2006) researched interaction among skinheads in a news group. Takahashi (2010), on the other hand, observed his informants’ everyday lives in front of the screen settings as well as their on-screen everyday lives through social networking sites.

Behaviour observation is often situated in experimental, not in a natural environment. Nagel & al. (2007) created the virtual online student Jane in order to improve students’ online learning success. Potential of networked technologies to facilitate different aspects of young people’s civic development was explored using Zora, a virtual city, in the context of a multicultural summer camp for youth. Eastin & Griffiths (2006) used six virtual game settings to study how game interface, game content and game context influence levels of presence and hostile expectation bias. In experimental research the creation of a virtual self, an avatar is exploited as one of the behavioural indicators. This is a part of the wider research interest in multi-user virtual environments (MUVE). Yee & al. (2009) found that people infer their expected behaviours and attitudes from observing their avatar’s appearance, while Bente & al. (2008) integrated a special avatar interface into a shared collaborative workspace to assess their influence on social presence, interpersonal trust, perceived communication quality, nonverbal behaviour and visual attention. Schroeder & Baileson (2008: 327) summarized the MUVEs advantages for research: subjects and researchers do not need to be co-located; virtual environments allow interactions that, for practical or ethical reasons, are not possible in the real world; all verbal and nonverbal aspects of the interaction can be captured accurately and in real time; and the social contexts and functional parameters of interactions can be manipulated in different ways. In communication journals MUVE research is used to advance our knowledge of mediated social behaviour and its transfer to offline situations.

Recording participant behaviour is a rather exploited advantage. Although large volumes of data can be easily collected in an objective and automated way, they offer «thin» descriptors because data recording devices on the Internet track only some aspects of the users’ behaviour. In order to get a richer picture of the phenomena under study, authors are using a combination of nonreactive data collection procedures (like log file data) with auto perception data. There are many authors who use these complementary data gathering techniques and triangulate them to achieve higher validity of results. For example, Ratan & al. (2010) linked survey data with unobtrusively collected game-based behavioural data from the Sony Online Entertainment large back-end databases.

4.3. Technical interactivity

Technical interactivity in the five analysed journals can be labelled as the ‘black hole’ in communication studies. Neither low interactivity, defined as zero control over technical characteristics of medium or medium structure, nor high technical interactivity, which includes modifications of the medium beyond the pre-given media options, receive any attention at all.

4.3.1. Medium technical interactivity

Medium technical interactivity which includes user control of the medium or system within pre-given possibilities is rarely researched on its own. Rather, it can be said that researchers have embraced various customization and personalization opportunities not as an object of research but as a tool to analyse other aspects of communicative behaviour. Scholars used technical interactivity either as independent variable in experimental design in researching social interaction or as one of the elements affecting textual interaction.

Usage of avatar customization is frequent in Proteus Effect research on the dependence of individuals’ behaviour on their digital self-representation (Yee & Bailenson, 2007), as well as in research around the concepts such as social presence or interpersonal trust (Bente & al., 2008). Yee & al. (2009), for example, placed their respondents in an immersive virtual environment and assigned them taller and shorter avatars and looked for variations in behaviour and attitudes depending on the avatar height variation. More towards textual interactivity, Farrar, Krcmar and Nowak (2006) analysed how two internal video games manipulations – the presence of blood which could be switched on or off, and the point of view which could be third or first person – influence perception and interpretation of the game.

In the research on medium technical interactivity, the focus is placed on interactive features of online newspapers and their effects on perceived satisfaction with the newspaper websites (Chung, 2008). Using web based survey to gather respondents’ opinions Chung and Nah (2009: 860) specifically examined increased choice options, personalization, customization and interpersonal communication opportunities offered as part of news presentation.

In similar fashion but using experimental design, combined with pre and post surveys, Kalyanaraman and Sundar (2006) created three different version of MyYahoo website to reflect three the conditions being high, low, medium levels of customization.

Among already rare studies of technical interactivity, a study of Papacharissi (2009) holds a special place as the author analyses the underlying structure of three social networking sites «with the understanding that they are all specified by programming code» (Papacharissi, 2009: 205). By employing comparative discourse analysis and analysis of content, aesthetics and structure of SNSs, Papacharissi examines how individuals modify, personalize and customize these spaces and the extent to which online architecture allows them to do so.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The primary classification of the selected articles, between the types and levels of interactivity, shows that the scholarly focus lies upon the low textual, followed by the high social interactive practices. This could be attributed to the fact that both areas are well situated objects of communication (sociology, psychology mass media) research, and as such they have relatively stable research agendas, concepts and methods. The high textual interactivity and the high technical interactivity are rarely researched, although in their novelty they are probably most challenging.

Investigations into the audience/user relations with texts are still orientated towards content, within the realm of media effects tradition. On the other hand, it is evident that the researchers are increasingly turning to communication practices of social network sites.

Each level of textual interactivity is related to a specific set of media practices and certain regularity in methods used can be noticed. For research of low textual interactivity survey and experiment prevail. The medium level exploits computer-mediated data gathering techniques, while higher level of textual interaction remains an under-researched area.

High social interaction seems to be a central preoccupation in communication studies, reviving the application of ethnographic methods. As Hine observes, «(R)ecognition of the richness of social interactions enabled by the Internet has gone hand in hand with the development of ethnographic methodologies for documenting those interactions and exploring their connotations» (Hine, 2008: 257).

The lowest subset of technical interactivity is not being examined, as unchangeable medium structure is ‘taken-for-granted’ in classic communication scholarship. In sharp opposition to traditional media, the new digital ones afford and invite tampering with the channel, an activity which from the early days of new technologies gave rise to numerous hacker practices. Still, activities such as modding of games or other software remain outside the dominant communication research agenda.

Looking specifically into methods we can identify innovation in data gathering techniques. In the new media environment, communicators leave traces of their behaviour. Therefore the use of log files and tracking procedures are new valuable sources of information for researchers.

In spite of technological developments the traditional methods like survey, content analysis and experiment are still frequent. There are certain transformations of these methods which can be regarded more as a technical progress than as an essential change. This can be seen in software assisted research and content creation in experimental design. With the proliferation of software tools, the question remains of how future research can achieve comparability and replicability, more and more often demanded by the research community.

References

Antony, M.G. & Thomas, R.J. (2010). ‘This is Citizen Journalism at its Finest’: YouTube and the Public Sphere in the Oscar Grant Shooting Incident. New Media & Society, 12(8), 1280-1296.

Balka, E. & al. (2010). Situating Internet Use: Information-Seeking among Young Women with Breast Cancer. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 15(3), 389-411.

Bente, G. & al. (2008). Avatar-Mediated Networking: Increasing Social Presence and Interpersonal Trust in Net-Based Collaborations. Human Communication Research, 34(2), 287-318.

Bollen, J. & al. (2009). A Principal Component Analysis of 39 Scientific Impact Measures. PLoS ONE, 4(6): e6022

Braun, T., Glanzel, W. & Schubert, A. (2006). A Hirsch-type Index for Journals. Scientometrics, 69(1), 169-173.

Buse, C.E. (2009). When you Retire, does Everything become Leisure? Information and Communication Technology Use and the Work/leisure Boundary in Retirement. New Media & Society, 11(7), 1143-1161.

Campbell, A. (2006). The Search for Authenticity: An Exploration of an Online Skinhead Newsgroup. New Media & Society, 8(2), 269-294.

Cheshire, C. & Antin, J. (2008). The Social Psychological Effects of Feedback on the Production of Internet Information Pools. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(3), 705-727.

Cho, H. & Lee, J.S. (2008). Collaborative Information Seeking in Intercultural Computer-Mediated Communication Groups: Testing the Influence of Social Context Using Social Network Analysis. Communication Research, 35(4), 548-573.

Chung, D.S. & Nah, S. (2009). The Effects of Interactive News Presentation on Perceived User Satisfaction of Online Community Newspapers. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 14(4), 855-874.

Chung, D.S. (2008). Interactive Features of Online Newspapers: Identifying Patterns and Predicting Use of Engaged Readers. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(3), 658-679.

Cover, R. (2006). Audience Inter/Active: Interactive Media, Narrative Control and Reconceiving Audience History. New Media and Society, 8(1), 139-158.

Eastin, M.S. & Griffiths, R.P. (2006). Beyond the Shooter Game: Examining Presence and Hostile Outcomes Among Male Game Players. Communication Research, 33(6), 448-466.

Farquhar, L. & Meeds, R. (2007). Types of Fantasy Sports Users and Their Motivation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1.208-1.228.

Farrar, K.M., Krcmar, M. & Nowak, K.L. (2006). Contextual Features of Violent Video Games, Mental Models, and Aggression. Journal of Communication, 56(2), 387-405.

Feely, T.H. (2005). A Bibliometric Analysis of Communication Journals from 2002 to 2005. Human Communication Research, 34(3), 505-520.

Gunter, B. (2003). News and the Net. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hine, C. (2008). Virtual Ethnography: Modes, Varieties, Affordances. In N. Fielding, R.M. Lee & G. Blank (Eds.), Online Research Methods. (pp. 257-270). London: Sage.

Hodkinson, P. (2007). Interactive Online Journals and Individualization. New Media & Society, 9(4), 625-650.

Interactivity. The International Communication Gazette, 71(5), 373-391.

Ivory, J. & Kalyanaraman, S. (2007). The Effects of Technological Advancement and Violent Content in Video Games on Players’ Feelings of Presence, Involvement, Physiological Arousal, and Aggression. Journal of Communication, 57(3), 532-555.

Jensen, J. (1999). Interactivity - Tracking a New Concept in Media and Commu-nication Studies. In P.A. Mayer (Ed.), Computer Media and Communication. (pp. 160-187). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kaigo, M. & Watanabe, I. (2007). Ethos in Chaos? Reaction to Video Files Depicting Socially Harmful Images in the Channel 2 Japanese Internet Forum. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1248-1268.

Kalyanaraman, S. & Sundar, S.S. (2006). The Psychological Appeal of Personalized Content in Web Portals: Does Customization Affect Attitudes and Behavior? Journal of Communication, 56(1), 110-132.

Kayany, J.M., Wotring, C.E. & Forrest, E.J. (1996). Relational Control and Interactive Media Choice in Technology-Mediated Communication Situations. Human Communication Research, 22(3), 399-421.

Kelleher, T. (2009). Conversational Voice, Communicated Commitment, and Public Relations Outcomes in Interactive Online Communication. Journal of Communication 59(1), 172-188.

Kim, Y.M. (2009). Issue Publics in the New Information Environment: Selectivity, Domain Specificity, and Extremity. Communication Research, 36(2), 254-284.

Kiousis, S. (2002). Interactivity: A Concept Explication. New Media and Society, 4(3), 355-383.

Knobloch-Westerwick, S. & Hastall, M. (2006) Social Comparisons with News Per-sonae: Selective Exposure to News Portrayals of Same-Sex and Same-Age Characters. Communication Research, 33(4), 262-284.

Koolstra, C.M. & Bos, M.J. (2009). The Development of an Instrument to Determine Different Levels of

Kurmis, A.P. (2003). Understanding the Limitations of the Journal Impact Factor. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 85, 2.449-2.454.

Ley, B.L. (2007). Vive Les Roses: The Architecture of Commitment in an Online Pregnancy and Mothering Group. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1.388-1.408.

Manovich, L. (2001). The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Markpin, T. & al. (2008). Article-count Impact Factor of Materials Science Journals in SCI database, Scientometrics, 75(2), 251-261.

McMillan, S. (2002). Exploring Models of Interactivity from Multiple Research Traditions: Users, Documents, Systems. In L. Lievrouw & S. Livingstone (Eds.), Handbook of New Media : Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs. (pp. 163-182). London: Sage.

Murphy, J., Hofacker, C. & Mizerski, R. (2006). Primacy and Recency Effects on Clicking Behavior. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2), 522-535.

Nagel, L.; Blignaut, S. & Cronjé, J. (2007). Methical Jane: Perspectives on an Un-disclosed Virtual Student, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1.346-1.368.

Oliver, M.B. & Bartsch, A. (2010). Appreciation as Audience Response: Exploring Entertainment Gratifications Beyond Hedonism. Human Communication Research, 36(1), 53-81.

Papacharissi, Z. (2009). The Virtual Geographies of Social Networks: A Comparative Analysis of Facebook, LinkedIn and ASmallWorld. New Media & Society, 11(1-2), 199-220.

Park, H.W. & Leydesdorff, L. (2009). Knowledge Linkage Structures in Communication Studies Using Citation Analysis among Communication Journals. Scientometrics, 81(1), 157-175.

Pfeil, U., Zaphiris, P. & Ang, C.S. (2006). Cultural Differences in Collaborative Au-thoring of Wikipedia. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(1), 88-113.

Rafaeli, S. & Ariel, Y. (2007) Assessing Interactivity in Computer-mediated Research. In: A. Joinson, K. McKenna, T. Postmes & U. Reips (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Internet Psychology. (pp. 71-88). New York: Oxford University Press.

Ratan, R.A., & al. (2010). Schmoozing and Smiting: Trust, Social Institutions, and Communication Patterns in an MMOG. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 16(1), 93-114.

Robinson, S. (2009). ‘If you had been with us’: Mainstream Press and Citizen Journalists Jockey for Authority over the Collective Memory of Hurricane Katrina. New Media & Society, 11(5), 795-814.

Schroeder, R. & Bailenson, J. (2008). Research Uses of Multi-user Virtual Envi-ronments. In N. Fielding, R.M. Lee & G. Blank (Eds.), Online Research Methods. (pp. 327-343). London: Sage.

Sohn, D. (2011). An Anatomy of Interaction Experience: Distinguishing Sensory, Semantic, and Behavioral Dimensions of Interactivity. New Media & Society, 13(8), 1320-1335.

Sweetser, K.D. & Kaid, L.L. (2008). Stealth Soapboxes: Political Information Efficacy, Cynicism and Uses of Celebrity Weblogs among Readers. New Media & Society, 10(1), 67-91.

Szuprowicz, B.O. (1995). Multimedia Networking. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Takahashi, T. (2010). MySpace or Mixi? Japanese Engagement with SNS (Social Networking Sites) in the Global Age. New Media & Society, 12(3), 453-475.

Thelwall, M. & Stuart, D. (2007). RUOK? Blogging Communication Technologies During Crises. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(2), 523-548.

Thorsen, E. (2008). Journalistic Objectivity Redefined? Wikinews and the Neutral Point of View. New Media & Society, 10(6), 935-954.

Tremayne, M. (2008) Manipulating Interactivity with thematically Hyperlinked News Texts: A Media Learning Experiment. New Media & Society, 10(5), 703-727.

Weber R. & al. (2009). What do we Really Know about First-Person-Shooter Games? An Event-Related, High-Resolution Content Analysis. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 14(4), 1.016-1.037.

Williams, D. (2006). Virtual Cultivation: Online Worlds, Offline Perceptions, Journal of Communication, 56(1), 69-87.

Wirth, W. & al. (2007). Heuristic and Systematic Use of Search Engines. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(3), 778-800.

Wise, K., Hamman, B. & Thorson, K. (2006). Moderation, Response Rate, and Message Interactivity: Features of Online Communities and their Effects on Intent to Participate. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(1), 24-41.

Wu, G., Xiaorui Hu, X. & Wu, Y. (2010). Effects of Perceived Interactivity, Perceived Web Assurance and Disposition to Trust on Initial Online Trust. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 16(1), 1-26.

Yaros, R.A. (2006). Is It the Medium or the Message? Structuring Complex News to Enhance Engagement and Situational Understanding by Nonexperts. Communication Research, 33(4), 285-309.

Yee, N. & Bailenson, J. (2007). The Proteus Effect: The Effect of Transformed Self-Representation on Behavior. Human Communication Research, 33(3), 271-290.

Yee, N., Bailenson, J.N. & Ducheneaut, N. (2009). The Proteus Effect: Implications of Transformed Digital Self-Representation on Online and Offline Behavior. Communication Research, 36(2), 285-312.

Zhou, Y. & Moy, P. (2007). Parsing Framing Processes: The Interplay between Online Public Opinion and Media Coverage. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 79-98.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El objetivo de este artículo es trazar las investigaciones alrededor del concepto de la interactividad e indicar las tendencias dominantes y las áreas poco investigadas. Está basado en el análisis del contenido de los métodos utilizados en los artículos publicados en las cinco revistas de comunicación más importantes por ranking durante un periodo de cinco años (200610). La evaluación de los métodos aplicados en la investigación de la interactividad se basa en la diferencia entre la interactividad social, la interactividad textual y la interactividad técnica. Se desarrolla esta clasificación de forma más profunda al añadir la categoría de los niveles de interactividad (baja, media y alta), lo cual permite una clasificación adicional de las varias prácticas medidas. Todo esto conduce a una especificación de nueve subconjuntos teoréticos de la interactividad como las categorías principales del análisis de los artículos evaluados para esta investigación. Dentro de esta matriz, hemos situado varios métodos que responden a unos tipos y niveles de interactividad del público/usuarios que son conceptualmente diferentes. El análisis demuestra que los investigadores se centran en las prácticas de la interactividad textual baja y la interactividad social alta, mientras que la interactividad técnica alta y la interactividad textual alta suscitan poco interés entre los académicos. Las investigaciones de las relaciones del público/usuario con los textos se orientan principalmente hacia el análisis del contenido y las encuestas. La investigación de la interacción social alta está reactivando la aplicación de los métodos etnográficos, mientras que las posibilidades de la interactividad técnica se aceptan no como un objeto de estudio sino como una herramienta de investigación.

1. Introducción

El avance de las tecnologías de comunicación ha ofrecido al público nuevos modos de comunicación, nuevos caminos y nuevas intersecciones de mensajes que cambian continuamente y que transforman el modelo lineal en lo que Gunter (2003) resumió como un modelo uno-a-uno, uno-a-muchos, muchos-a-muchos y muchos-a-uno de comunicación pública. La transformación de las tecnologías de comunicación ha autorizado «poderes» a un público anteriormente pasivo con herramientas para cambiar/colaborar en la creación de contenido, determinar/involucrarse en el ritmo de la interacción social con el autor/el público y participar en la estructura tecnológica y arquitectural de los medios al producir nuevos códigos digitales actuales con capacidad de desbloqueo. La interactividad, aunque sigue siendo un concepto muy polémico en los estudios de los medios y de la audiencia, se convierte en algo útil en la interrogación de la transformación bosquejada del sistema social de la comunicación y del público como partes inherentes a ella.

Este artículo define la interactividad como la diferencia específica que excede y engloba los cambios que dan forma a la nueva ecología de los medios. El objetivo es trazar las investigaciones alrededor del concepto de la interactividad, indicar las corrientes significativas y las áreas menos investigadas y situar los diversos métodos que responden conceptualmente a los tipos diferentes y niveles de prácticas interactivas.

2. El concepto de la interactividad

El primer obstáculo que se encuentra en la investigación de la interactividad es el problema de delimitar y definir de forma operativa el propio concepto. Aunque la interactividad ha sido un tema de investigación relevante durante las últimas tres décadas, incluso los estudios más recientes se ven obligados a empezar con una explicación del concepto (Sohn, 2011; Koolstra & Bos, 2009; Rafaeli & Ariel, 2007; McMillan, 2002; Kiousis, 2002). Una revisión de investigaciones anteriores demuestra que los obstáculos se pueden agrupar así:

Primero, el concepto tiene su teoría y se usa en muchas disciplinas desde la ciencia informática, las ciencias de la información, la publicidad y el marketing hasta los estudios de los medios. Por eso se define desde muchas perspectivas diferentes.

Segundo, hay una diferencia entre la interactividad basada en las características y la interactividad basada en la percepción. Varios autores definen la interactividad o bien como un elemento estructural del medio (Manovich, 2001) o como una percepción variable de la mente del usuario (Wise, Hamman & Thorson, 2006). En el contexto de este artículo no entramos en este debate; sostenemos que la interactividad actual no se puede contrastar estrictamente con la interactividad percibida como un estado psicológico tal y como lo experimenta el usuario. O bien, como indican Rafaeli & Sudweeks (1997, citado en Cover, 2006: 141), la interactividad no es una característica del medio sino una construcción relacionada con el proceso sobre la comunicación.

Tercero, la naturaleza dimensional de la interactividad. La multidimensionalidad del concepto se ha determinado por las interrelaciones entre: la frecuencia, la gama y la importancia; el sentido de la comunicación, el control del usuario y el tiempo; la velocidad, la gama y la facilidad del manejo del contenido por parte de los usuarios; o bien por el grado de la relación secuencial entre mensajes (Jensen, 1999).

Szuprowicz (1995) presenta un enfoque más unificado e identifica tres dimensiones de la interactividad: usuario-a-usuario, usuario-a-documentos y usuario-a-ordenador (usuario-a-sistema). Este enfoque puede ser un buen punto de partida para profundizar en la exploración de la interactividad, ya que examina las relaciones del público con los tres componentes cruciales de cualquier comunicación mediada: el contenido, otros participantes y la tecnología. Además, la conceptualización de la interactividad a través de estas tres dimensiones lleva a un marco que encuadra muchos enfoques y perspectivas diferentes y que nos aporta un abanico de posibilidades bastante amplias las cuales necesitamos en esta investigación. Con todo esto, nos fijamos en el tratamiento dimensional de la interactividad ya presentado, lo cual hemos etiquetado así:

• La interactividad social (la interacción entre usuarios).

• La interactividad textual (la interacción entre el usuario y los documentos).

• La interactividad técnica (la interacción entre el usuario y el sistema).

Otro asunto polémico que incide en la teoría y la investigación de los medios es el grado o nivel de la interactividad. Básicamente, la cuestión radica en el alcance de la interacción entre los usuarios, los textos y los sistemas. Primero Kayany, Wotring & Forrest (1996) y después McMillan (2002) sugieren que los usuarios imponen un tipo de control relacional (o interpersonal), de contenido (o textual) y de proceso/secuencia (o basado en la interface). Aunque dentro del marco de McMillan el nivel de control no es la única dimensión de interactividad, es la única que resulta relevante para todos los tipos de interacción.

En función de estos argumentos, proponemos que la interactividad definida como el control sobre el texto, la interacción social y el medio se puede subdividir en tres niveles: bajo, medio y alto, según el control que los usuarios sean capaces de imponer. Esto significa que, dentro de cada tipo de control, se puede identificar y analizar los varios grados de la interactividad.

Si pensamos en la interactividad como un continuo de prácticas variadas, la actividad del público como recipientes en el flujo clásico de la comunicación de masas estaría en la parte más baja, mientras las acciones parecidas a las que desarrollan el productor o los participantes en la comunicación interpersonal se encontrarían en el polo opuesto, en la parte más alta. En algunas prácticas, el público no tiene la posibilidad de controlar ninguna de las tres dimensiones de la interactividad. Por ejemplo, no pueden iniciar la comunicación, cambiar el texto ni tener influencia sobre los otros participantes en la comunicación. Indicamos que esto no se puede considerar como una situación de control cero, porque incluso en la típica situación de comunicación de masas el público puede parar la comunicación o controlar los textos mediáticos de forma interpretativa. Estos niveles bajos de la interacción son las semillas que crecerán para convertirse en niveles más altos de control por parte del público (Cover, 2006).

El nivel medio de interactividad se refiere a las actividades en las cuales el público ejerce control pero dentro de unos parámetros y reglas predeterminados. En cuanto a la interactividad social, esto significa que los autores han previsto y aportado unos canales para que los usuarios puedan responder y mantener la interacción. El nivel medio de la interactividad textual se relaciona con esas situaciones en las cuales se invita a los usuarios a participar activamente en la construcción del contenido mediático. En el caso de la interactividad técnica, el nivel medio de control debe verse como un productor que tiene la oportunidad de participar en la co-construcción de algunas partes de la arquitectura del medio. En el nivel alto de la interactividad se supone que existe una libertad que los propios usuarios han conseguido más allá del nivel de control deseado por los productores-creadores, que quieren quedarse con este control.

La intersección de las dimensiones de la interactividad ya descritas con sus niveles de control (tabla 1) se encuentra en el modelo teórico de la interactividad que se utilizará en este artículo para investigar las tendencias y los métodos empleados en la investigación de la comunicación.

3. Método

En la selección de las revistas de comunicación para un estudio nos enfrentamos con un problema general y otro que se refiere específicamente al tema. El problema general se relaciona con la polémica sobre la evaluación de la revista entre los círculos académicos y de los cientométricos. Después de décadas de prevalencia del factor de impacto de la revista que se aplicó a las revistas de la base de datos de la Red de Ciencia, han ido apareciendo en los últimos diez años unos métodos nuevos (p.ej.: h-factor: Braun & al., 2006), EigenfactorTM (www.eigenfactor.org), Article-Count Impact Factor (Markpin & al., 2008, entre otros). Sin embargo, no hay acuerdo sobre un método común dado que cada uno de ellos acepta algunas pero rechaza otras de las características de las revistas (Bollen & al., 2009). Consciente de sus limitaciones, hemos optado por el factor de impacto de la revista como criterio de inclusión, ya que es el método más utilizado en el análisis de las revistas de comunicación (Feely, 2005) y por los comités de promoción y de revisión de becas (Kurmis, 2003). Se leen y se citan las revistas con un factor de impacto más alto y por eso éstas marcan tendencias en el mundo de la investigación.

El «Journal Citation Reports» de la «Web of Science», el más significativo a la hora de emprender este trabajo, referenció 55 revistas en el campo de la comunicación para el año 2009. El problema, que se relaciona específicamente con el tema de la interactividad, es que este listado refleja la diversidad de las tradiciones intelectuales y la atomización de los dominios de la investigación dentro de la comunicación. Para captar una muestra más amplia de intereses en este campo, hemos seleccionado las revistas que, según Park y Leydesdorff (2009), se encajan en «el sector de la investigación de la comunicación». Entre las primeras 10 revistas del ranking (basado en su factor de impacto) se encuentran «Journal of Communication» (IF 2.415, ranking: 2/55), «Human Communication Research» (IF 2.200, ranking: 3/55), «Communication Research» (IF 1.354, ranking: 8/55) y «New Media and Society» (IF 1.326, ranking: 10/54). No se incluyeron la Psicología General ni la Psicología relacionada con asuntos de la salud, como otros dos sectores primarios entre las revistas de la comunicación (Park & Leydesdorff, 2009: 169), pero sí se incluyó el «Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication» (IF 3.639, ranking: 1/55) ya que fue la revista de mayor impacto en 2009, y está publicada por la asociación de investigación de la comunicación más grande (ICA) y, lo que resulta más importante, el alcance de sus temas prometió una investigación sobre las formas interactivas por medio del ordenador. Para conseguir una muestra representativa para el análisis de los métodos y las tendencias, analizamos los artículos publicados durante un periodo de cinco años (2006-10).

Cuando empezamos a componer una muestra de revistas, la típica investigación bibliométrica a través de las palabras claves nos resultó insuficiente, dado que la palabra interactividad no se mencionó explícitamente, aunque se examinaron algunos aspectos de este tema. Incluimos esos artículos que consideraron la interactividad como un elemento en el proceso de la comunicación, con o sin una explicación del término. También, nos interesaron esos artículos que presentaron una investigación empírica, ya que el objetivo de nuestro estudio es el de aportar perspectivas sobre los métodos utilizados por los diferentes tipos y niveles de la interactividad. Nuestro tercer criterio fue que el objetivo del análisis es la comunicación pública o semi-pública. Según la tipología propuesta, decidimos conservar la mínima condición de «sentido de audiencia» aunque reconocemos el cambio indicado por los nuevos términos como consumidores y usuarios. Con el uso de esos tres criterios, sacamos 98 artículos para el análisis.

Analizamos el contenido de estos artículos usando el software NVivo 9. Las variables dependientes del código se definen como los tipos de la interactividad (social, textual, técnico) y los niveles de la interactividad (bajo, medio, alto). Los autores se encargaron de la codificación.

Para desarrollar una definición precisa de las variables y resolver los dilemas, los autores discutieron a fondo los 10 artículos incluidos en la muestra de fiabilidad por intercodificador, y se sometieron otros 40 artículos a una evaluación de fiabilidad por intercodificador. Se resolvieron las discrepancias por mayoría simple (2 de los 3) y estos 50 artículos formaron parte de la muestra completa. Dado que la fiabilidad por intercodificador, calculada con un porcentaje medio por pareja, fue 0,93 (tabla 2), se codificaron los otros 48 artículos de forma independiente. Aplicamos un enfoque algo diferente, dada la frecuencia de los métodos empleados en la investigación empírica. Usamos el software NVivo para codificar la información sobre los métodos tal y como aparecen en los textos. Ya que esta información se da de forma explícita, se añaden los nodos y subnodos correspondientes a cada método en la forma en que aparece en un artículo.

4. Resultados

La mayoría de los 98 artículos analizados se publicaron en «Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication», «New Media y Society» y «Communication Research» (tabla 3). No se ha encontrado ninguna tendencia en cuanto al interés de los investigadores por examinar los varios tipos y niveles de la interactividad, por lo menos durante estos cinco años (tabla 3). Sin embargo, la muestra indica que hay un interés constante en la interactividad en general, ya que la distribución de los artículos por año varía en solo un 6%, oscilando entre el más bajo, 17%, en 2006 y el más alto, 23%, en 2007.

Los autores se interesan por la interactividad textual baja y la interactividad social alta mientras se observa que la interactividad técnica no suscita mucho entusiasmo (tabla 4). Hay solamente dos artículos que tratan de todos los tipos de la interactividad. En cuanto a los métodos, los autores presentan unas investigaciones basadas en encuestas sobre el uso general de las características de la comunicación on-line. Hay 12 artículos más en los cuales se estima que hay dos tipos de interactividad de igual importancia, y en la mayoría (10 de los 12) se da una combinación de la interactividad social alta y la interactividad técnica media.

La tabla 5 muestra la distribución de los métodos de investigación dentro de la matriz de los tipos y niveles de interactividad. En la siguiente sección hablamos de este tema en más profundidad.

4.1. La interactividad textual

Los artículos clasificados en el subconjunto de la interactividad textual baja se concentran más en las actividades de texto que en las actividades del público. Las actividades con hipertexto y multinarrativas se consideran como una actividad media, mientras la co-creación del contenido se califica como una forma de interactividad alta. Los investigadores siguen la tendencia dominante de la investigación de la comunicación fijándose en el contenido sin la participación del público (tabla 4).

4.1.1. La interactividad textual baja

El paradigma de los efectos mediáticos es un marco teórico prevalente en el trato de las prácticas de la interactividad textual baja. Los investigadores están interesados en: a) los efectos de un tipo específico de contenido mediático (p.ej.: la cirugía cosmética, programas de maquillaje y peluquería, historias sobre las donaciones de órganos como entretenimiento televisivo) sobre el comportamiento de la audiencia; b) el impacto de unas características textuales (fuentes, tipos de narrativa, presentación, el género de los personajes) sobre el público. El público de los nuevos medios se trata como una interacción textual baja sin tener en cuenta las posibilidades ofrecidas por el medio digital. Por ejemplo, incluso los juegos de ordenador se han investigado como cualquier otro tipo de contenido mediático, sin reconocer el papel del usuario en la creación de la narrativa o en la modificación de los ajustes (Ivory & Kalyanaraman, 2007; Williams, 2006).

Se trata el comportamiento del público también desde la perspectiva de los usos y las gratificaciones para investigar unos aspectos específicos del uso del medio, como la gratificación de ver una película (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010), los motivos para la participación en los concursos de deportes de fantasía (Farquhar & Meeds, 2007) o los patrones del uso de un sitio web (Yaros, 2006).

Hay dos métodos que predominan en la investigación de la interactividad textual baja: la encuesta y el experimento. Se utiliza la encuesta para recoger información sobre la televisión y los usuarios-el público de los nuevos medios, y el diseño experimental se aplica casi exclusivamente a la investigación de Internet y a los comportamientos de los usuarios de los videojuegos.

Los resultados indican que hay nuevas formas en la comunicación por medio del ordenador que facilitan la manipulación de los textos para poder examinar los efectos de los mensajes, lo cual permite a los investigadores controlar las características textuales y examinar las reacciones del público con una precisión y certeza más alta (Yaros, 2006; Knobloch-Westerwick & Hastall, 2006). Se hizo poca investigación cualitativa y es una excepción del patrón predominante. Por ejemplo, para Buse (2009) es la forma de investigación más adecuada para determinar cómo las tecnologías informáticas se relacionan con las experiencias del trabajo y del ocio entre unos jubilados, mientras Kaigo y Watanabe (2007) realizan un análisis cualitativo sobre la reacción a unos archivos de vídeo que demuestran unas imágenes perniciosas en un foro online en Japón.

4.1.2. La interactividad textual media

La investigación de la interactividad textual media se centra en los nuevos medios, especialmente en las páginas web y los foros online; hay dos excepciones, las cuales se concentran en los juegos de ordenador. Las actividades del público que más suscitan el interés de los investigadores son la búsqueda de información, especialmente relacionada con los asuntos de la salud (Ley, 2007; Balka & al, 2010) y la lectura de hipertextos.

La monitorización del comportamiento del usuario a través de los programas que registran el comportamiento del público en la web es la técnica utilizada con más frecuencia para recoger datos sobre la interactividad textual media. Se organiza esta monitorización alrededor del sitio más natural para los usuarios (Kim, 2009) o bien, como ocurre con más frecuencia, en unas condiciones controladas y generadas en el laboratorio (Murphy, 2006; Tremayne, 2008). Para aportar más información sobre el significado de los datos recogidos por ordenador, los investigadores necesitan una percepción de los motivos e intenciones de los participantes, y por eso se utilizan con frecuencia las encuestas (Wu & al., 2010; Wirth & al., 2007; Kim, 2009), aunque se aprovechan también de los protocolos de pensamiento en voz alta o las medidas de las reacciones psicológicas dentro de un marco experimental (Weber & al., 2009).

Hoy en día hay métodos ya consolidados que resultaron más difíciles de aplicar en ambientes mediáticos anteriores, como la recogida de las narrativas del público, los correos electrónicos, foros y blogs. Además, se utiliza hoy el análisis del contenido para comprender mejor las selecciones y búsquedas de los participantes mientras usan un buscador (Wirth & al., 2007) y el comportamiento de los usuarios de los videojuegos (Weber & al., 2009).

4.1.3. La interactividad textual alta

Los pocos artículos (4) que hay sobre la creación de contenido colaborativo demuestran el poco interés entre los investigadores por examinar este tema. Se han investigado dos clases de contenido Wiki: Wikinews (Thorsen, 2008) y Wikipedia (Pfeil & al., 2006) y los dos se basan en el análisis del contenido de los productos colaborativos pero sin examinar los procesos realizados en la co-creación del contenido. Cheshire y Antin (2008), a través de un experimento de campo con Internet, investigaron la correlación entre las reacciones que recibe el autor y su disposición de enviar otro mensaje. Se exploró, utilizando una encuesta por Internet, la disposición del ciudadano de enviar su propio contenido a un periódico local online (Chung, 2008).

4.2. La interactividad social

Durante mucho tiempo se investigaron las interacciones sociales, en la mayoría de los casos, desde la perspectiva de la sociología y la psicología, que se interesaron en la comunicación interpersonal no mediada. Hoy en día, este tema es relevante para los estudios de los medios de comunicación porque las nuevas tecnologías facilitan los encuentros interpersonales dentro los marcos proporcionados por los medios. La irrupción de los foros, las redes sociales y otras plataformas sociales despertó un gran interés entre los científicos y nuestros resultados lo confirman. La mayoría de los artículos se refieren a los diversos aspectos de las prácticas que se etiquetan como la interactividad alta, porque son las más parecidas a la comunicación cara-a-cara, lo cual es el prototipo de la interacción más alta posible. El número de los artículos que pertenecen a la categoría de la interactividad social media es cinco veces más pequeño (tabla 3). La interacción para-social con el «autor», definido como la interactividad social baja, no figura en las investigaciones, lo cual resulta comprensible dado que en la nueva realidad de los medios hay una interacción social autentica, e incluso alta, con los comunicadores típicos a distancia (los famosos, los periodistas, etc.).

4.2.1. La interactividad social media

Se alcanza la interactividad social media cuando el público tiene la oportunidad de comunicarse con los autores del contenido mediático a través del envío de comentarios o la participación en los programas en directo, y así tiene un control parcial sobre la interacción. El cambio desde el típico público de la comunicación de masas a un público blog es evidente y lógico porque la interacción social media está incorporada en la definición del blog. Se han investigado los patrones del comportamiento y de las actitudes de los usuarios de los blogs a través de encuestas online (Sweetser & Kaid, 2008; Kelleher, 2009). También se ha estudiado el uso de un log online escrito en el estilo de un diario, con una observación de participantes a largo plazo y con entrevistas exhaustivas (Hodkinson, 2007).

El análisis del contenido de los comentarios en los blogs, en los portales de noticias o en YouTube es prominente en esta área de investigación, por eso se utiliza el texto como indicador del nivel medio de la interacción social (Robinson, 2009; Antony & Thomas, 2010). Comparado con el análisis del contenido tradicional, la envergadura de los estudios ya mencionados se ha extendido considerablemente. Por ejemplo, Thelwall & Stuart (2007), aplicando unos métodos semi-automáticos para detectar la frecuencia de ciertas palabras durante una crisis, sacaron conclusiones de los comentarios en los blogs y las fuentes web. Los envíos de mensajes online también se han utilizado para evaluar la importancia de los marcos que contienen diversas opiniones en comparación con la relevancia de los varios marcos mediáticos, como en la investigación del establecimiento de temas de discusión (Zhou & Moy, 2007).

Parecido a la manipulación de los textos, hay experimentos sociales en la creación de los blogs y la observación del comportamiento de los participantes. Por ejemplo, Cho & Lee (2008) montaron un foro para los estudiantes de tres universidades diferentes y analizaron la frecuencia de los envíos de comentarios en relación con los factores socioculturales.

4.2.2. La interactividad social alta

Las interacciones a través de las varias redes sociales on-line, o bien la interactividad social alta, forman un campo muy fértil para la investigación en las revistas de comunicación. Se aplican dos métodos principales de investigación que dependen de la orientación investigativa del autor, o bien hacia el control (el experimento) o el naturalismo (la etnografía). El diseño experimental se desarrolla normalmente con encuestas y la etnografía a través de las entrevistas. El experimento de campo aparece como un método diseñado para incluir unos elementos de los dos.

La tradición etnográfica ha florecido en los últimos 20 años debido en parte a la aparición de las numerosas comunidades online. En los artículos analizados, los métodos de la etnografía virtual van desde la observación de las comunidades online a la exploración de sus conexiones con la vida cotidiana. Al meterse en un grupo materno on-line, Ley (2007) estudió la importancia de la arquitectura del sitio web para el compromiso de sus miembros con sus grupos de apoyo online, mientras Campbell (2006) investigó la interacción entre los cabezas rapadas en un grupo de noticias. Por otro lado, Takahashi (2010) observó las vidas cotidianas de sus corresponsales en el marco de estar delante de la pantalla y sus vidas cotidianas en pantalla a través de las redes sociales.

La observación del comportamiento se estudia a menudo dentro de una realidad experimental en vez de un ambiente natural. Nagel y colaboradores (2007) crearon al estudiante virtual online llamado Jane para mejorar el éxito del aprendizaje estudiantil online. Se exploraron las posibilidades que tienen las tecnologías de las redes para facilitar los aspectos diferentes del desarrollo cívico de los jóvenes con el uso de Zora, una ciudad virtual, en el contexto de un campamento de verano multicultural para jóvenes. Eastin y Griffiths (2006) utilizaron seis marcos de juegos virtuales para estudiar cómo el interface y el contenido y contexto del juego influyen en los niveles de presencia y el prejuicio de expectativas hostiles. En la investigación experimental se aprovecha de la creación de un yo virtual, un avatar, como indicador de comportamiento. Esto forma parte de un área de investigación más extendida en los ambientes virtuales multiusuarios (MUVE, en inglés). Yee y otros (2009) encontraron que la gente deduce los comportamientos y actitudes que se esperan de ellos a través de la observación de la apariencia de su avatar, mientras que Bente y colaboradores (2008) integraron una interface de avatar especial en un espacio laboral compartido y colaborativo para evaluar su influencia sobre la presencia social, la confianza interpersonal, la calidad de comunicación percibida, el comportamiento no verbal y la atención visual. Schroeder y Baileson (2008: 327) resumieron las ventajas de los MUVE para la investigación: los sujetos y los investigadores no necesitan estar localizados conjuntamente; los ambientes permiten unas interacciones que, por razones prácticas o éticas, no son posibles en el mundo real; todos los aspectos verbales y no verbales de la interacción se pueden captar con precisión y en tiempo real; y los contextos sociales y los parámetros funcionales se pueden manipular de forma diferente. En las revistas de comunicación, las investigaciones sobre los MUVE se utilizan para avanzar nuestro conocimiento del comportamiento social mediado y de su transferencia a situaciones off-line.

La grabación del comportamiento del participante es una herramienta bien consolidada. Aunque se pueden recoger muchos datos de forma objetiva y automatizada, éstos aportan unos descriptores de escaso valor porque los mecanismos usados para grabar los datos en Internet solamente siguen algunos aspectos del comportamiento del usuario. Para conseguir una perspectiva más profunda del fenómeno de este estudio, los autores utilizan una combinación de procedimientos no reactivos de recogida de datos (como los datos de los archivos del log) con los datos de auto-percepción. Hay muchos autores que utilizan estas técnicas de recogida de datos complementarios y los triangulan para conseguir una validez de resultados más alta. Por ejemplo, Ratan y otros (2010) vincularon los datos de encuestas con los datos de comportamiento de los usuarios de videojuegos recogidos de forma discreta de las grandes bases de datos de acceso indirecto de Sony Online Entertainment.

4.3. La interactividad técnica

Se puede clasificar la interactividad técnica en las cinco revistas analizadas como el «agujero negro» de los estudios de la comunicación. Ni la interactividad baja, definida como el control cero sobre las características técnicas del medio, ni la interactividad técnica media y alta, esta última incluye las modificaciones del medio más allá de las opciones mediáticas predeterminadas, reciben la más mínima atención investigativa.

4.3.1. La interactividad técnica media

Pocas veces se encuentra una investigación que examine en exclusiva la interactividad técnica media, que incluye el control del usuario del medio o del sistema dentro de unas posibilidades dadas de antemano. Más bien, los investigadores han considerado las varias oportunidades presentadas por la personalización y la adaptación al gusto del usuario no como un objeto de investigación, sino como una herramienta para analizar otros aspectos del comportamiento comunicativo. Los investigadores utilizaron la interactividad técnica o bien como un variable independiente en el diseño experimental durante la investigación de la interacción social, o bien como uno de los elementos que afecta la interacción textual.

El uso de la personalización del avatar es frecuente en la investigación Proteus Effect sobre la dependencia del comportamiento del individuo sobre su auto-representación digital (Yee & Bailenson, 2007), y en la investigación sobre conceptos como la presencia social o confianza interpersonal (Bente & al., 2008). Yee y otros (2009), por ejemplo, colocaron a sus participantes en una realidad virtual inmersiva y les asignaron unos avatares más altos y otros más bajos, y luego buscaron cambios en el comportamiento y en las actitudes que dependían del cambio de altura del avatar. Más cerca de la interactividad textual, Farrar, Krcmar y Nowak (2006) analizaron cómo las manipulaciones internas de dos videojuegos –la presencia de sangre que se podía mostrar o ocultar, y el punto de vista que podía ser de primera o tercera persona– afectaron a la percepción y la interpretación del juego.

La investigación de la interactividad técnica media se centra en las características interactivas de los periódicos online y sus efectos sobre la satisfacción percibida con los portales de prensa (Chung, 2008). Con el uso de una encuesta online para recoger las opiniones de los participantes, Chung y Nah (2009: 860) examinaron específicamente el incremento de las opciones de elección, la personalización y las oportunidades ofrecidas por la comunicación interpersonal como parte de la presentación de las noticias.

De forma parecida pero usando el diseño experimental combinado con encuestas de antes y después, Kalyanaraman y Sundar (2006) crearon tres versiones diferentes del portal MyYahoo para demostrar las tres condiciones (bajo, medio y alto) de la personalización.

Entre los pocos estudios que existen sobre la interactividad técnica, un estudio de Papacharissi (2009) tiene una relevancia especial dado que el autor analiza la estructura subyacente de tres redes sociales «con el entendimiento de que están todos especificados por códigos de programación» (Papacharissi, 2009: 205). El autor utilizó un análisis de discurso comparativo y un análisis del contenido, y la estética y estructura de los SNS para analizar cómo los individuos modifican y personalizan estos espacios, y hasta qué punto la arquitectura online les permite hacerlo.

5. Discusión y conclusión

La clasificación inicial de los artículos seleccionados, entre los tipos y niveles de la interactividad, demuestra que la mayoría de las investigaciones se centran en la interactividad textual baja, seguido de la interactividad social alta. Esto se puede atribuir al hecho de que las dos áreas son objetos de la investigación de la comunicación bien situados (la sociología, la psicología y la comunicación de masas), y como tal tienen unos programas de investigación, conceptos y métodos bastante estables. La interactividad textual alta y la interactividad técnica alta se investigan poco aunque representan el reto más exigente por su novedad.

Las investigaciones de las relaciones del usuario/público con los textos todavía se orientan hacia el contenido, dentro del ámbito de la tradición de los efectos de los medios. Por otro lado, es evidente que los investigadores recurren cada vez más a las prácticas comunicativas que se llevan a cabo en las redes sociales.

Cada nivel de interactividad textual se relaciona con un conjunto específico de prácticas mediáticas y se nota una cierta regularidad en los métodos utilizados. En la investigación de la interactividad textual baja predominan la encuesta y el experimento. La interactividad textual media explota las técnicas de recogida de los datos por medio de ordenador, mientras la interacción textual alta sigue sin ser investigada a fondo.

La interacción social alta parece ser una preocupación central en los estudios de la comunicación, en lo cual se ve una vuelta a la aplicación de los métodos etnográficos. Como afirma Hine (2008: 257), el «reconocimiento de la riqueza de las interacciones sociales permitidas por Internet ha acompañado el desarrollo de las metodologías etnográficas en la documentación de esas interacciones y la exploración de sus connotaciones».

El subconjunto más bajo de la interactividad técnica no se está investigando dado que la estructura del medio inmutable «se toma por hecho» en la investigación clásica de la comunicación. A diferencia de los medios tradicionales, los digitales ofrecen e invitan a los usuarios a realizar ajustes al canal, una actividad que, desde los inicios de las nuevas tecnologías, ha dado origen a las numerosas prácticas de los hackers. Las actividades como el «modding» de los juegos o de otros tipos de software son prácticas ajenas del programa dominante de la investigación de la comunicación.

Al considerar específicamente los métodos, identificamos la innovación en las técnicas de recogida de datos. En la nueva realidad de los medios, los comunicadores dejan rastros de su comportamiento. Por eso, el uso de los archivos de los logs y la monitorización de los procedimientos son nuevas fuentes valiosas de información para los investigadores.

A pesar de los desarrollos tecnológicos, los métodos tradicionales como la encuesta, el análisis del contenido y el experimento se siguen utilizando con frecuencia. Hay ciertas transformaciones de estos métodos que se pueden considerar más como un progreso técnico que como un cambio esencial. Esto se ve en la investigación asistida por software y la creación de contenido en el diseño experimental. Con la proliferación de las herramientas de software, la pregunta sigue siendo la misma: ¿cómo pueden conseguir las investigaciones del futuro esa comparabilidad y replicabilidad exigida cada vez más por los investigadores?

Referencias

Antony, M.G. & Thomas, R.J. (2010). ‘This is Citizen Journalism at its Finest’: YouTube and the Public Sphere in the Oscar Grant Shooting Incident. New Media & Society, 12(8), 1280-1296.

Balka, E. & al. (2010). Situating Internet Use: Information-Seeking among Young Women with Breast Cancer. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 15(3), 389-411.