(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== The w...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 861772236 to Ramirez et al 2012a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 12:06, 29 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The work below examines the attitudes and beliefs that secondary teachers have about the use of Internet resources in their practices. It is presented results obtained from a questionnaire (n=1,721) with different dimensions, obtaining data about teachers’ attitudes and reasons with respect to the use of Internet resources, respect to teachers’ tasks employed for and respect to training teachers received about Internet resources. The study use descriptive and correlation data of answers percentages to questionnaire items. Results show that attitudes are very important to explain the use of these resources in classroom practices. Also, the role that teachers’ perception about their digital competencies plays over the possibility to use Internet resources in their classroom practices. These results show differences between teacher in function of age and genre. Finally, teachers’ training about Internet has a positive effect on self perception about digital competencies. The results point to the need of research on what beliefs could explain why teachers decide to use or not Internet resources, how they use them and which factors are included.

1. Introduction

The interest in investigating teachers’ beliefs, conceptions and knowledge, which have been referred to as teacher thoughts or cognitions (Calderhead, 1996), is due to the key role these constructs play when explaining what teachers do in the classroom (Kagan, 1992; Pajares, 1992), as well as the changes they steadily embrace (Putman & Borko, 1996). This same notion is shared by researchers into the incorporation of ICTs into educational processes, who posit that the beliefs and conceptions teachers hold regarding the use of ICTs have a key role to play when explaining the processes of deploying these resources in the classroom (Ertmer, 2005; Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007, Aguaded & Tirado, 2008, Mominó de la Iglesia, Sigalés & Meneses, 2008, Froufe, 2000). The aim of this paper is to study this issue, specifically attitudes and motivations regarding the use of ICTs associated with the Internet, as expressed by secondary teachers using these resources. This goal requires clearly delimiting the perspective from which the subject is to be addressed, as the present confusion on the study of teachers’ conceptions and beliefs has meant that the results from research into the matter have not had a major explanatory impact on teachers’ training and practices (Chan & Elliot, 2004; Pajares, 1992; Fang, 1996).

2. Teachers’ beliefs - what are we referring to?

The term “beliefs” has been used in very different ways and with very different meanings in research involving teachers. As reported by Pajares (1992), terms such as beliefs, values, attitudes, ideologies, conceptions and pre-conceptions, personal theories and implicit theories have been difficult to differentiate in the array of standpoints adopted in research in this field.

For our purposes here, the most pertinent distinction is the one established between beliefs and knowledge. Beliefs have a more implicit nature and operate in a less consistent manner than knowledge, whereby they manifest themselves in specific practical situations or in episodes, aiming to be of use in the resolution of this specific situation rather than providing long-term efficacy and validation. Beliefs, which also have a cognitive component, do not seek “the truth” through scientific deduction, but utility instead (Pozo, 2000), creating personal theories that are marked by the social and practical nature that defines them and renders them of such use to people as formal or scientific knowledge (Pozo & Rodrigo, 2001).

According to Nespor (1987), beliefs are formed through experiences that are always linked to personal events and circumstances, so they include feelings, emotions and assessments, memories of past personal experiences, suppositions on the existence of alternative beings and realities, which are not open to outside evaluation or to critical reasoning. They are gradually built up within a vast system that is constantly being reorganised according to the structure and framework of knowledge.

The power this framework of beliefs exerts upon teaching practices is extremely important, among other things because of the role beliefs play in each teacher’s activities. Regarding the matter in question here, namely, the use of Internet resources by secondary teachers, the impact teachers’ beliefs about their work has on classroom practice has been well reported (Lumpe, Haney & Czerniak, 2000; Mishra & Koehler, 2006), although it has yet to be made absolutely clear whether teaching beliefs have a direct influence on the use of ICTs in the classroom (Wozney, Venkatesh & Abrami, 2006). We can mention research results that reveal how different aspects related to teachers’ beliefs and attitudes regarding these technologies are crucial to their use. For example, the beliefs that teachers hold about their own teaching performance are closely linked to their practices, so favourable attitudes towards technologies and a positive perception of one’s own digital competence have proven to be prior conditions for the use of computers in teaching (Paraskeva et al., 2007). On the other hand, and in a study conducted by McGrail (2005), teachers referred to the disadvantages of the use of ICTs alluding to teaching considerations associated with the pupils, the teaching process, ethical issues…These teachers were not at all clear about how to adapt the technologies to their teaching styles or how to include them in the syllabus. Furthermore, in a study by Mueller et al. (2008), one of the critical features that distinguished those teachers who successfully used such technologies from those who did not was their attitude towards these resources, studied according to a scale measuring the degree to which teachers considered a computer to be a viable and productive technology and a cognitive tool that could make an appropriate contribution to their teaching activities. Generally speaking, studies on teachers’ attitudes and beliefs regarding ICTs, and the Internet in particular, focus on three points:

1) Positive attitudes towards these resources increase the probability they will be used.

2) These positive attitudes are closely linked to the perception teachers have of their own digital competence.

3) Digital competence alone does not explain the use of ICTs in practical contexts. This competence has to be linked moreover to the belief that teaching will be enhanced by the use of ICTs. In other words, digital competence increases the likelihood of using ICTs for professional purposes, provided this is consistent with the teaching beliefs held by the teachers themselves (Groves & Zemel, 2000).

Nevertheless, although it seems clear that teachers’ beliefs about ICTs condition their use in practice, it is not obvious how to alter these beliefs with a view to extending the use of these technologies in the classroom. Along these lines, some of the more realistic proposals do not rely on changing the teachers, but rather on reconsidering the design of ICT resources (Groves & Zemel, 2000). This would involve, therefore, bringing the technological design closer to the syllabus content through such measures as producing digital materials similar to traditional ones to render them compatible with common teaching approaches to classroom subjects. Other authors (Ertmer, 2005), basing themselves on the principle that changes in beliefs can be triggered by personal experiences, vicarious experiences and socio-cultural influences, stress the need for teachers to experience for themselves or through colleagues the positive results of the use of technological resources in the classroom.

In sum, the preceding review points to the need to understand that the beliefs and attitudes teachers have regarding ICTs constitute one of the factors explaining the use of these resources in the classroom. The aim of this paper, therefore, will be to discover the beliefs held by secondary teachers regarding the use of ICTs related to the Internet. More specifically, we shall set out to use the data gathered using a questionnaire with Likert-type scale questions to analyse attitudinal considerations and the motivational ones informing these beliefs, as these aspects have a bearing on the use of digital resources in teaching methodologies, and whether the Internet training received impacts upon teachers’ attitudes and beliefs regarding this medium. In short, we are therefore seeking to unravel the framework of beliefs on ICTs as regards teachers and their relationship with the use or not of these resources.

3. Material and methods

3.1. Sample

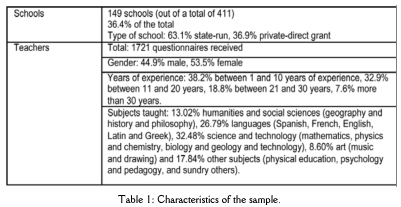

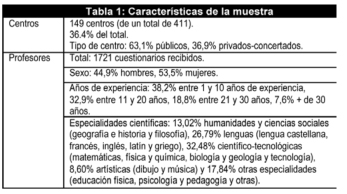

In order to conduct this research, we sent out questionnaires, as described forthwith in the Procedure section, to 411 schools - just about all the schools teaching compulsory secondary education in the Spanish region of Castilla y León. The characteristics of the sample used are described in Table 1 below:

3.2. Procedure

The first stage of the procedure involved preparing the data-gathering instrument. A questionnaire was drawn up that addressed a total of five dimensions. This paper presents data from three of them, as are: (a) attitudes towards Internet resources in relation to the teachers’ professional duties; (b) methodological aspects of teaching with the Internet, and (c) Internet training received. Likert-type scales were used for dimensions a and b, with 4 and 5 levels of choice (Hinojo & Fernández, 2002).

The process of preparing the questionnaire was undertaken in several stages, with the last one involving a review of the same by ten secondary school teachers from different subjects. Once all the reviews had been made, the Cronbach’s alpha for all the items on the Likert-type scales gave a result of 0.89. The questionnaires were sent to all the schools in the sample, and a check was made to ensure they had all been received correctly. Finally, the results received were encoded and loaded into a data matrix that allowed an analysis to be conducted through the SPSS 15.0 statistical program in order to provide the results presented here.

4. Results

The organisation of the results in this section responds to the goal we are pursuing. We therefore first present the percentage data from the answers on attitudes and reasons that the teachers have provided on Internet use in the classroom, together with the correlations of these two aspects according to gender, years of experience and subject taught, using chi-squared tests. Secondly, we present the correlation data that describe the impact the teachers’ attitudes and reasons regarding Internet use have on their teaching methods. Thirdly, we provide data to show whether the Internet training received has a bearing on attitudes and reasons regarding the use of this resource among the teachers involved in our research.

4.1 Teachers’ attitudes and reasons regarding Internet use

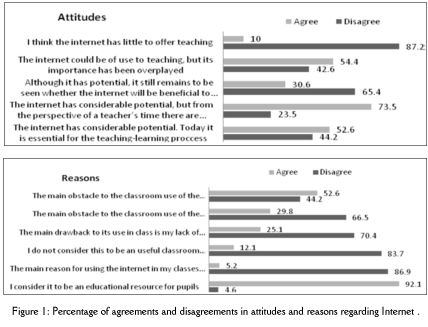

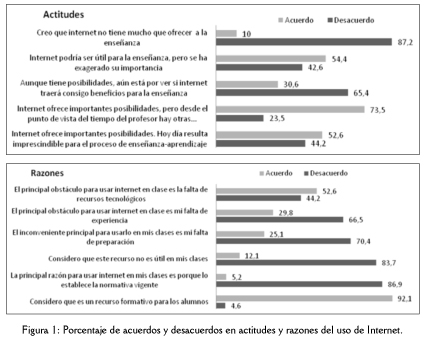

First, Figure 1 presents the results showing the extent to which teachers do or do not agree with the use that can be made of the Internet in teaching, as well as the reasons explaining why they do or do not use these resources. We can see that the general trend indicates that the highest values correspond to positive attitudes towards this matter. Accordingly, over half the secondary teachers surveyed state that they agree or strongly agree with the fact that the resources provided by the Internet today are essential for teaching. Furthermore, 87.2% disagree or strongly disagree with the notion that Internet resources have little to offer and their usefulness has been overplayed. Therefore, according to these data, we can make the point that teachers have a positive attitude towards Internet resources for classroom use.

Figure 1: Percentage of agreements and disagreements in attitudes and reasons

Regarding Internet use

As for the motives or reasons teachers give for whether or not they use the Internet, it can be seen (Figure 1) that practically all the teachers agree (92.1%) that one of the reasons for using the Internet is its educational value for pupils. Another reason that appears to merit the agreement of over half the students is the lack of resources available to them (52.6%), although this notion contrasts with the disagreement (44.2%) that the teachers also record in this same item. Likewise, most of the teachers seem to disagree with the fact that Internet resources are of no use in teaching (83.7%) and that the legal obligation to use them (86.9%) or a lack of training and experience (70.4%, 66.5%) are reasons or motives that explain the classroom use or not of the Internet. In short, the reasons that secondary teachers give as the ones carrying the most weight for the use of Internet resources in their classes involve mainly what they consider as favouring the pupils’ learning experience, as well as being of use to their classroom practices. As we can see, these results are consistent with the positive attitude that most teachers have towards the Internet.

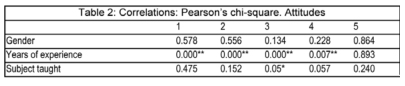

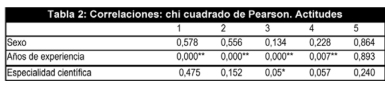

Once the data have been gathered on the teachers’ attitudes and reasons regarding the use of the Internet’s digital resources, our focus now turns to discovering whether there are differences in these attitudes and reasons according to the variables of gender, years of experience and the subjects taught by the teachers in the sample. The results obtained accordingly are shown in Tables 2 (attitudes) and 3 (reasons). The correlation analyses conducted through Pearson’s chi-squared coefficient (Table 2) reveal significant relationships between the attitudes variable and other teacher variables, such as years of experience and the subject taught. In this sense, regarding gender, the most significant result is that being male or female does not have a major impact on the attitudes teachers have towards the use of the Internet in the classroom. In terms of years of experience, all the attitudes items correlate significantly, with the exception of item 5, which is not significant. The significant and positive relationships between these two variables suggest that the more positive attitudes towards the Internet are even stronger among those teachers with fewer years of experience (under 10) than among those with more experience (over 15 years). The subject variable throws up significant differences for item 3, revealing a somewhat sceptical attitude towards the use of Internet in teaching solely in the subjects we have listed under science and technology.

- The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level *The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level.

1) I think the Internet has little to offer teaching. 2) The Internet could be of use to teaching, but its importance has been overplayed. 3) Although it has potential, it still remains to be seen whether the Internet will be beneficial to teaching. 4) The Internet has considerable potential, but from the perspective of a teacher’s time there are other priorities. 5) The Internet has considerable potential. Today it is essential for the teaching-learning process.

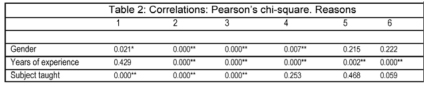

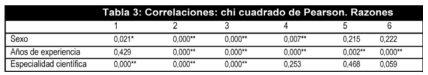

Regarding the relationships between the reasons for use and other variables such as experience, gender and subject (Table 3), we have found results that reveal important issues. In general, we find highly significant differences between the various items in the reasons dimension and the different levels of experience. All the answers to this dimension are significant at the 0.01 confidence level according to the years of experience, except for the item: “The main obstacle to the classroom use of the Internet is a lack of technological resources”. A detailed analysis of the results reveals that the longer a person has been in teaching, the more they will be in agreement regarding lack of experience, training and usefulness as reasons for not using the Internet in class. Furthermore, the groups of teachers with more experience are the ones who consider this resource has no educational use for pupils, as opposed to the younger ones who do consider it to be educational and useful, although they consider the lack of resources to be an obstacle. On the other hand, the gender variable also marks significant differences regarding the reasons for using the Internet. Women are the ones who affirm they do not use the Internet for reasons of lack of resources, experience and training, and because they do not consider the Internet to be useful. Finally, the subject taught also leads to significant differences (0.01 confidence level) regarding the items of lack of resources, experience and training. This means that although the subjects of languages and humanities and social sciences are the ones with the closest agreement with the lack of experience and training as reasons for explaining the non-use of the Internet, in the case of “The main obstacle to the classroom use of the Internet is a lack of technological resources”, the art subjects also use it as an argument, as opposed to science and technology subjects where there is disagreement with this statement.

- The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level *The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level

1) The main obstacle to the classroom use of the Internet is a lack of technological resources. 2) The main obstacle to the classroom use of the Internet is my lack of experience. 3) The main drawback to its use in class is my lack of training. 4) I do not consider this to be a useful classroom resource. 5) The main reason for using the Internet in my classes is that I am legally required to do so. 6) I consider it to be an educational resource for pupils.

4.2. Impact of attitudes and reasons regarding the use of the Internet on teaching methodologies

There follows a description of the results of the cross-analyses between the dimensions of teaching methodologies applied in class and the resources associated with the Internet, attitudes towards its use and reasons for such use. The data provided below are designed to study in greater detail the relationship between the attitudes and beliefs of the teachers in the sample and the methodology they apply in class.

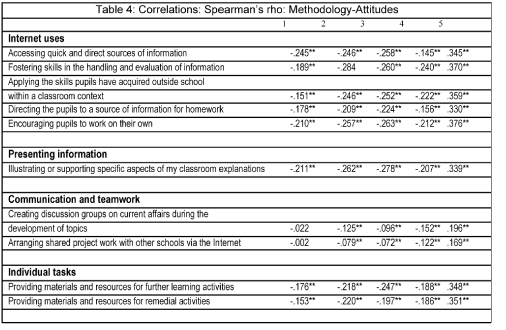

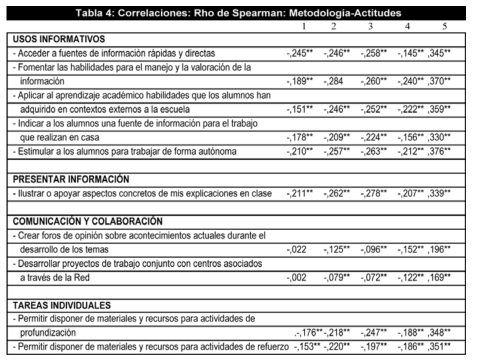

Appearing first in Table 4 are the results of the correlations between the methodology dimension (specifying the teaching tasks using Internet resources) and the attitudes held by teachers. The results are clear: practically all the correlations are significant at a 0.01 level. The indices have a negative sign when the attitudes item is formulated in this direction, which means that negative attitudes correlate with the non-use of the Internet for teaching activities, whereas the positive ones do so with the application of those activities in the teacher’s classroom practices. The correlations have a positive sign when the items are formulated in a positive way, which corroborates the trend we have just explained: positive attitudes towards the Internet are associated with the application of Internet resources to teaching activities and vice versa. This general pattern is qualified, showing that attitude is what defines the methodology to be applied with the Internet in class, both for those activities involving the presentation and handling of information, where the greatest significant effects are to be found (p= .376), and for communication and teamwork methodologies, with the smallest significant effects (p=.169).

- The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral) *The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (bilateral) 1) I think the Internet has little to offer teaching 2) The Internet could be of use to teaching, but its importance has been overplayed 3) Although it has potential, it still remains to be seen whether the Internet will be beneficial to teaching 4 The Internet has considerable potential, but from the perspective of a teacher’s time there are other priorities 5) The Internet has considerable potential. Today it is essential for the teaching-learning process

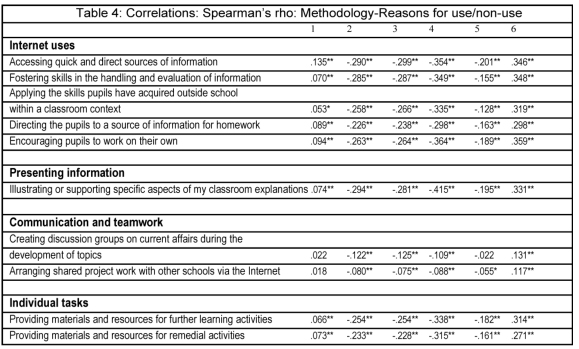

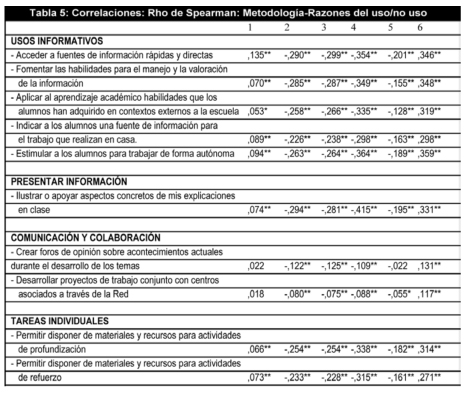

Secondly, Table 5 contains the correlation results obtained in the analysis of the reasons teachers allude to regarding their teaching methods involving the use of the Internet. It can be affirmed that the arguments carrying the most weight for explaining the use or not of the Internet for their teaching activities are related to the perception teachers have of their experience and training, the usefulness of the Internet for their classes and legal requirements. This means that the correlations between the items we have just listed are all significant at a 0.01 level and negative. Therefore, those teachers that perceive themselves as having a lack of experience or a lack of training are the ones who least use the Internet in class. Likewise, those teachers who consider the Internet resource to be of no use for their classes do not include it in their work either. Those who do not agree that legal requirements are the main reason for using the Internet in their classes are the ones who most use this medium in their teaching activities. On the other hand, a lack of resources as an obstacle to the use of the Internet in class correlates significantly with practically all teaching practices, with the exception of communication and teamwork, which have an anecdotic impact on their application. Yet this result in relation to the item involving a lack of resources reveals that the ones most using the Internet for teaching practices are also the ones who place the most stress on the lack of resources. This means that a lack of resources is not the aspect with the most weight for explaining the reason whether or not the Internet is used in a teacher’s activities. Finally, a reason that clearly explains the use of the Internet made by teachers is the understanding that this resource has an educational role to play for pupils, as can be seen in the correlation indices listed in Table 5.

- The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral) *The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (bilateral) 1) The main obstacle to the classroom use of the Internet is a lack of technological resources 2) The main obstacle to the classroom use of the Internet is my lack of experience 3) The main drawback to its use in class is my lack of training 4) I do not consider this to be a useful classroom resource 5) The main reason for using the Internet in my classes is that I am legally required to do so 6) I consider it to be an educational resource for pupils

4.3. Repercussion of the Internet training received on attitudes and reasons for use among teachers

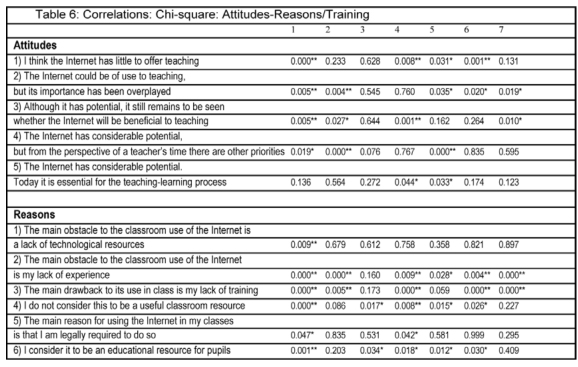

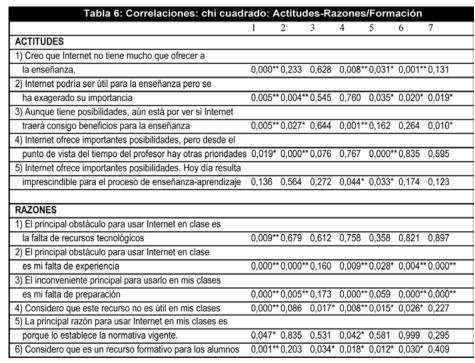

Finally, Table 6 contains the correlation results between teachers’ attitudes and reasons and the Internet training received. Two aspects stand out in our analysis of the results in these dimensions. Firstly, regarding attitudes, although in general we have already indicated that teachers seem to share positive attitudes towards the Internet, those that have received training during their degree courses or their professional careers at Spain’s Teacher Training and Innovation Centres (CFIEs) and other institutions are the ones who by far reveal the most positive attitudes towards the use of the Internet. Secondly, those teachers who have received training, whatever its nature, are the ones who consider themselves to have a greater level of digital competence, as they are the ones who do not consider a lack of experience or a lack of training to be the main obstacle to Internet use in the classroom, and in most of the items this difference is significant at a 0.01 confidence level. It would be of greater interest to study these data in more detail in order to gain more comprehensive information on the type of training received in terms of content and the teaching methodologies used, as it appears to have been put to good use.

- The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level *The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level

1) Initial training: as an undergraduate; 2) Initial training: Master’s degree; 3) Initial training: courses; 4) Lifelong training: CFIE courses; 5) Lifelong training: Master’s degree; 6) Lifelong training: evening classes 7) Self-taught.

5. Discussion

In the light of these data, we can affirm that the profile of beliefs among the secondary teachers in our sample is informed by two basic aspects: on the one hand, the educational value attributed to Internet resources and, on the other, the knowledge of these resources that is attributed to teachers. Regarding the former, age constitutes a differentiating factor between positive and negative attitudes, with negative ones being linked to older age groups. Regarding the latter, the knowledge of resources, the difference is marked by age and gender, with a lower attribution of digital competence among women and older age groups. Finally, training, especially at an initial stage, although also that provided by CFIE teacher training centres, has a positive impact on the assessment teachers make of their own digital competence.

These data ratify what other scholars have found, thereby enabling us to focus on certain aspects with major ramifications for classroom practices.

Firstly, it seems clear that attitudes have a fair degree of influence on the use of Internet resources in classroom practices. Although these attitudes are generally positive, those teachers who consider that these resources have no educational value do not use them in the classroom and this relationship is significant above all in older age groups, as is also reported in the work by Paraskeva et al. (2007). Yet in addition to attitude, the perception teachers have of their digital competence also seems to explain the likelihood they will use Internet resources in their teaching activities. In this case, moreover, the differences are due not only to age, but also to the teachers’ gender. Nevertheless, although the role beliefs play in the attribution of the competence itself seems to be a crucial one for the adoption of the resources, the Internet training received is effective for improving this digital competence.

Secondly, these results show that the issue of beliefs and attitudes must necessarily be included on the agenda for research into the use of ICTs in teaching practices and, in particular, the use of the Internet as a teaching resource. An in-depth study is required to uncover the beliefs that specifically explain the adoption or otherwise of these innovations, how they are shaped and the elements that define them, as well as to investigate the training received regarding the Internet, content, educational approaches, as it is a reason that explains the change in the perception of professional competence in terms of these resources. Finally, it is important to pursue lines of research that connect the teaching approaches of teachers with beliefs on ICTs in general and the Internet in particular, given the link that appears to exist between the two factors, without losing sight of how it is all indeed implemented in the practical contexts in which teaching-learning processes actually take place.

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted thanks to the funds provided by project SA060A06 of the regional government, the Junta, of Castilla y León.

References

Aguaded, J.I. & Tirado, R. (2008). Los centros TIC y sus repercusiones didácticas en primaria y secundaria en Andalucía. Educar, 41; 61-90.

Calderhead, J. (1996). Teachers: Beliefs and Knowledge. In Berliner, D. & Calfee, R. (Eds.), Handbook of Edu-cational Psychology. New York: Macmillan; 709-725.

Chan, K-W. & Elliott, R.G. (2004). Relational Analysis of Personal Epistemology and Conceptions about Teaching and Learning. Teacher and Teaching Education, 20 (2004); 817-831.

Ertmer, P.A. (2005). Teacher pedagogical beliefs. The final frontier in our quest for technology integration? Educational Technology Research and Development, 53(4); 25-39.

Fang, Z. (1996). A Review of Research and Teacher Beliefs and Practices. Educational Research, 38 (1); 47-65.

Froufe, S. (2000). Análisis crítico de las actitudes bloqueadoras de la comunicación humana. Comunicar, 14; 97-102.

Groves, M. & Zemel, P. (2000). Instructional technology adoption in higher education: an action research case study. International Journal of Instructional Media, 27 (1); 57-65.

Hinojo, J. & Fernández, F. (2002). Diseño de escala de actitudes para la formación del profesorado en tecno-logías. Comunicar, 19; 120-125.

Kagan, D.M. (1992). Implications of Research on Teacher Belief. Educational Psychologist, 27(1); 65-90.

Koehler, M.J. & Mishra, P. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108; 1.017-1.054.

Lawless, K. & Pellegrino, J. (2007). Professional Development in Integrating Technology into Teaching and Learning: Knowns, Unknowns, and Ways to Pursue Better Questions ans Answers. Review of Educational Research, 77; 575-614.

Lumpe, A.T.; Haney, J.J. & Czerniak, C.M. (2000). Assessing Teachers’ Beliefs about Their Science Teaching Context. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37; 275-292.

Mcgrail, E. (2005). Teachers, Technology and Change: English Teachers’ Perspectives. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13; 5-24.

Mominó, J.M.; Sigales, C. & Meneses, J. (2008). L’escola a la societat xarxa: Internet a l’Educació Primària i Secundària. Barcelona: Ariel y UOC.

Mueller, J.; Wood, E.; Willoughby, T.; Ross, C. & Specht, J. (2008). Identifying Discriminating Variables between Teachers who Fully Integrate Computers and Teachers with Limited Integration, Computers and Education (doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.02.003) (01-07-2011).

Nespor, J. (1987). The Role of Beliefs in the Practice of Teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19; 317-328.

Pajares, M.F. (1992). Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning up a Messy C Construct. Review of Educational Research, 62; 307-332.

Paraskeva, F. & al. (2007). Individual Characteristics and Computer Self-efficacy. Computers & Education (doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2006.10.006) (01-07-2011).

Pozo, J.I. (2000). Concepciones de aprendizaje y cambio educativo. Revista Ensayos y Experiencias, 33; 4-13.

Pozo, Y. & Rodrigo, M.J. (2001). Del cambio de contenido al cambio representacional en el conocimiento conceptual. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 24 (4); 3-22.

Putnam, R., & Borko, H. (1997). Teacher learning: Implications of new views of cognition. In Biddle, B.; Good, T. & Goodson, I. (Eds.). The International Handbook of Teachers and Teaching. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1.223-1.296.

Wozney, L.; Venkatesh, V. & Abrami, P.C. (2006). Implementing Computer Technologies: Teachers’ Perceptions and Practices. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 14; 120-173.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

En este trabajo se estudian las actitudes y creencias que los profesores de secundaria tienen sobre la utilización de los recursos de Internet en sus prácticas. Se presentan los resultados obtenidos aplicando un cuestionario (n=1.721) que abarca diversas dimensiones, obteniéndose datos respecto de las actitudes de los profesores en relación al uso o no de recursos de Internet, a las tareas docentes para las que se emplean y con la formación recibida al respecto. Se ofrecen datos de los porcentajes de respuestas a los ítems del cuestionario e índices correlacionales. Entre los resultados destaca la relación entre las actitudes de los profesores y el que introduzcan estos recursos en sus prácticas, así como el papel que juega la edad y el sexo de los profesores en estas actitudes. También se pone de relieve la relación entre la creencia de los profesores en su competencia digital y la probabilidad de que utilicen los recursos de la Red en sus prácticas. Por último, lo resultados destacan la relación que aparece entre la formación recibida sobre Internet y las diferencias en la percepción sobre competencia digital de los docentes. Los resultados subrayan la necesidad de estudiar en profundidad cuáles son las creencias que explican de forma específica la adopción o no de estos recursos digitales, cómo se conforman y qué elementos las definen.

1. Introducción

El interés por conocer las creencias, concepciones y conocimientos de los profesores, lo que algunos autores han denominado pensamientos o cogniciones del profesor (Calderhead, 1996), se debe al papel central que estos constructos juegan a la hora de explicar lo que los profesores hacen en sus prácticas (Kagan, 1992; Pajares, 1992), así como los cambios que van incorporando (Putman & Borko, 1996). Esta misma idea es compartida por las investigaciones sobre la incorporación de las TIC a los procesos educativos, las cuales conceden a las creencias y concepciones que los profesores mantienen sobre el uso de las TIC, un papel fundamental a la hora de explicar los procesos de incorporación de estos recursos en las aulas (Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007, Aguaded & Tirado, 2008, Mominó de la Iglesia, Sigalés & Meneses, 2008; Froufe, 2000). En este trabajo nos proponemos estudiar este asunto, concretamente las actitudes y motivos hacia el uso de los recursos TIC asociados a Internet, que mantienen los profesores de secundaria que utilizan dichos recursos. Este objetivo exige delimitar claramente la perspectiva desde la que se va a abordar ya que la confusión existente sobre el estudio de las concepciones y creencias de los profesores ha provocado que los resultados de la investigación sobre el tema no hayan tenido una gran repercusión explicativa sobre la formación y práctica de los profesores (Chan & Elliot, 2004; Pajares, 1992; Fang, 1996).

2. Creencias de los profesores: ¿a qué nos estamos refiriendo?

El término creencias ha sido utilizado en las investigaciones con profesores de muy diferentes maneras y sentidos. Como señala Pajares (1992), términos como creencias, valores, actitudes, ideologías, concepciones, reflexiones a priori, teorías personales, teorías implícitas, han sido difíciles de diferenciar en las variadas perspectivas de investigación sobre el tema.

Para nuestros objetivos, la distinción más pertinente es la que se establece entre creencias y conocimiento. Las creencias tienen una naturaleza más implícita y operan de una manera menos consistente que el conocimiento, de tal forma que se manifiestan en situaciones prácticas concretas o en episodios, buscando la utilidad en la resolución de esa situación concreta más que la eficacia y validación a largo plazo. Las creencias, que tienen también un componente cognitivo, no buscan «la verdad» a través de la deducción científica, sino la utilidad (Pozo, 2000); creando teorías personales que vienen marcadas por el carácter social y práctico que las define y que hace que sean tan útiles a las personas como los conocimientos formales o científicos (Pozo & Rodrigo, 2001).

Según Nespor (1987), las creencias se conforman a través de experiencias que están siempre asociadas a situaciones y sucesos personales, por lo que incluyen sentimientos, afectos y evaluaciones, memorias de experiencias personales vividas, supuestos sobre la existencia de entidades y mundos alternativos, los cuales no están abiertos a la evaluación externa o al razonamiento crítico. Se van constituyendo en un gran sistema que cada vez se reorganiza en relación con la estructura o entramado del conocimiento.

El poder que este entramado de creencias ejerce sobre cómo se configuran las prácticas docentes resulta muy importante, entre otras cosas, por el papel que desempeñan en el ejercicio de la práctica. En el tema que nos ocupa, la incorporación de los recursos de Internet por parte de profesores de secundaria, el impacto que las creencias pedagógicas de los profesores tiene sobre las prácticas de clase, está bastante bien documentado (Lumpe, Haney & Czerniak, 2000; Koehler & Mishra 2006), aunque no quede del todo claro si existe una influencia directa de las creencias pedagógicas sobre la integración de las TIC en las prácticas (Wozney, Venkatesh & Abrami, 2006). Así podemos citar resultados de investigaciones que demuestran cómo diferentes elementos relacionados con las creencias y actitudes de los profesores sobre las tecnologías son determinantes para su uso. Por ejemplo, las creencias que los profesores mantienen sobre su propia eficacia docente están estrechamente relacionadas con sus prácticas, consecuentemente las actitudes favorables hacia las tecnologías y una percepción positiva de la propia competencia digital se han mostrado como condiciones previas para la incorporación del ordenador en la enseñanza (Paraskeva & al., 2007). En otro orden de cosas y en un estudio llevado a cabo por McGrail (2005), los profesores expresaban las desventajas de la incorporación de las TIC cifrándolas en asuntos pedagógicos relacionados con los alumnos, con el proceso de enseñanza, con temas éticos… Para estos profesores no resultaba nada evidente cómo ajustar las tecnologías a sus estilos de enseñanza o cómo integrarlas en el currículum. También en el estudio de Mueller y otros (2008), uno de los rasgos críticos que distinguía a los profesores que integraban con éxito las tecnologías de aquéllos que no lo hacían era las actitudes hacia estos recursos, estudiadas por medio de una escala que medía el grado hasta el cual el profesor estimaba que el ordenador era una tecnología viable, productiva, una herramienta cognitiva cuyo uso resultaba apropiado para sus prácticas docentes. Con carácter general, los estudios sobre actitudes y creencias de los profesores hacia las TIC, y hacia Internet en particular, ponen de relieve tres asuntos:

1) Las actitudes positivas hacia estos recursos aumentan la probabilidad de que se haga uso de los mismos.

2) Estas actitudes positivas están muy ligadas a la percepción que el profesor tiene de su propia competencia digital.

3) La competencia digital, por sí misma, no explica el uso de las TIC en los contextos prácticos. Esta competencia ha de vincularse además a la creencia en la mejora de la enseñanza a través de las TIC. Es decir, la competencia digital aumenta la posibilidad de utilizar las TIC para usos profesionales, siempre que sea coherente con las creencias pedagógicas que sostienen los profesores (Groves & Zemel, 2000).

Por otra parte, si bien parece claro que el papel de las creencias de los profesores sobre las TIC explica su incorporación a las prácticas, no resulta evidente cómo modificar dichas creencias con vistas a incorporar las tecnologías a las prácticas. En este sentido, algunas de las propuestas más realistas no basan sus presupuestos en los cambios de los profesores, sino en el replanteamiento de los diseños de los recursos TIC (Groves & Zemel, 2000). De esta manera, se trataría, por ejemplo, de acercar el diseño tecnológico a los contextos de la práctica con medidas como producir materiales digitales similares a los tradicionales, compatibles con los enfoques didácticos habituales de las materias del currículum. Otros autores (Ertmer, 2005), apoyándose en el principio de que los cambios en las creencias pueden suscitarse a través de experiencias personales, experiencias vicarias e influencias socioculturales, subrayan la necesidad de que los docentes experimenten por sí mismos o a través de otros colegas resultados positivos de prácticas de integración de recursos tecnológicos en las aulas.

En resumen, la revisión realizada hasta el momento nos señala la necesidad de conocer las creencias y actitudes que los profesores mantienen sobre las TIC como uno de los factores que explican el uso de estos recursos en las prácticas de aula. Por tanto, en este trabajo nos planteamos conocer qué creencias mantienen los profesores de secundaria sobre el uso de las TIC asociadas a Internet. De manera más concreta nos planteamos analizar, a través de los datos obtenidos de un cuestionario con preguntas tipo escala likert, los elementos actitudinales y motivacionales que las conforman, cómo dichos elementos repercuten en la incorporación de los recursos digitales a las metodologías docentes y si la formación recibida sobre Internet afecta a las actitudes y creencias instructivas en torno a dicho soporte. Buscamos, en síntesis, llegar a establecer el entramado de creencias sobre TIC de los docentes y su relación con el uso o no de estos recursos.

3. Material y métodos

3.1. Participantes

Para llevar a cabo la investigación se enviaron los cuestionarios que explicaremos en el epígrafe de procedimiento a 411 centros que representaban prácticamente el total de los centros de secundaria obligatoria de Castilla y León. Las características de la muestra sobre la que se trabajó aparecen descritas en la tabla 1 a continuación:

3.2. Procedimiento

La primera fase del procedimiento consistió en la elaboración del instrumento de recogida de los datos. Se elaboró un cuestionario en el que se abordaron cinco dimensiones en total. En este trabajo se presentan datos de tres de ellas, a saber: a) Actitudes respecto a los recursos de Internet en relación a tareas profesionales de los docentes; b) Aspectos metodológicos de las prácticas docentes con Internet; c) Formación recibida sobre Internet. Para la dimensiones a y b se usaron escalas tipo Likert, con 4 y 5 grados de elección (Hinojo & Fernández, 2002).

El proceso de elaboración del cuestionario se llevó a cabo en varias etapas, la última de las cuales consistió en la revisión del mismo por parte de 10 profesores de enseñanza secundaria, pertenecientes a distintas especialidades científicas. Después de todas las revisiones realizadas, el a de Cronbach en los ítems de las escalas tipo Likert dio un resultado de 0.89. Se enviaron los cuestionarios a todos los centros de la muestra, comprobando que se habían recibido correctamente. Por último, se codificaron las respuestas recibidas y se volcaron en una matriz de datos que permitió el análisis a través del programa estadístico SPSS 15.0 para establecer los resultados que presentamos en este trabajo.

4. Resultados

La organización de los resultados de este apartado atiende al objetivo que nos ocupa. Así, presentaremos, en primer lugar, los datos de porcentaje de respuesta sobre las actitudes y razones que los profesores manifiestan hacia el uso de Internet en el aula, junto con las correlaciones de estos dos elementos en función del sexo, años de experiencia y especialidad científica obtenidas a través de pruebas de chi cuadrado. En segundo lugar, presentaremos los datos correlacionales que describen la incidencia de las actitudes y las razones de los profesores en torno al uso de Internet sobre sus metodologías docentes. Y en tercer lugar, ofrecemos datos sobre si repercute la formación recibida acerca de Internet sobre las actitudes y razones del uso de este recurso en los profesores de nuestra investigación.

4.1 Actitudes y razones de los profesores hacia el uso de Internet

En primer lugar, en la figura 1 se recogen los resultados que reflejan en qué grado los profesores están de acuerdo o no con la utilidad que puede ofrecer Internet en la docencia, así como las razones que explican el porqué utilizan o no estos recursos. Podemos observar que la tendencia general muestra que los valores más altos se encuentran en las actitudes positivas hacia este tema. De este modo, más de la mitad de los profesores de secundaria encuestados afirman estar de acuerdo (bastante y muy de acuerdo) con que los recursos que ofrece Internet, hoy en día, resultan imprescindibles para la docencia. Por el contrario, el 87,2% se muestra en desacuerdo (bastante y muy en desacuerdo) con la idea de que los recursos que ofrece la Red tengan mucho que ofrecer y que se ha exagerado su utilidad. Por tanto, desde estos datos, podemos subrayar que la actitud de los profesores hacia los recursos que ofrece la Red para la práctica docente es positiva.

Figura 1: Porcentaje de acuerdos y desacuerdos en actitudes y razones del uso de Internet

En lo que respecta a los motivos o razones que manifiestan los profesores para usar o no usar Internet, se puede comprobar (figura 1) que prácticamente todos los profesores están de acuerdo (92,1%) con que una de las razones para utilizar Internet es su valor formativo para los alumnos. Otra razón con la que parecen estar de acuerdo más de la mitad de los profesores es con la falta de recursos de los que disponen (52,6%), aunque esta idea se ve contrarrestada con el desacuerdo (44,2%) que manifiestan también los profesores hacia esta misma razón. Igualmente, la mayoría de los profesores parecen estar en desacuerdo con que la no utilidad de los recursos de la Red en la docencia (83,7%), la obligación de la normativa (86,9%) o la falta de preparación y de experiencia (70,4%, 66,5%) sean razones o motivos que explican el uso o no de Internet en el aula. En definitiva, las razones que los profesores de secundaria manifiestan como más significativas para usar los recursos de la Red en sus clases tienen que ver, principalmente, con que lo consideran favorecedor del aprendizaje de los alumnos, además de útil para el desempeño de sus clases. Estos resultados, como podemos constatar, están en consonancia con la actitud positiva que manifiestan la gran mayoría de los profesores hacia Internet.

Una vez obtenidos los datos sobre las actitudes y razones que mostraban los profesores en relación al uso de los recursos digitales de Internet, nos interesa analizar si existen diferencias en dichas actitudes y razones en función de variables como el sexo, los años de experiencia y la especialidad científica de los docentes de la muestra. Los resultados obtenidos a este respecto se muestran en las tablas 2 (actitudes) y 3 (razones).

Los análisis correlacionales realizados a través del coeficiente chi cuadrado de Pearson (tabla 2), revelan relaciones significativas de la variable actitudes con otras variables del profesor como son los años de experiencia y la especialidad académica. En este sentido, respecto al sexo, el resultado más destacable es que el hecho de ser hombre o mujer no marca diferencias significativas con las actitudes que los profesores mantienen hacia el uso de Internet en el aula. Respecto a los años de experiencia todos los ítems de actitudes correlacionan de manera significativa, menos el ítem 5 que no resulta significativo. Las relaciones significativas y positivas entre estas dos variables nos están indicando que las actitudes más positivas hacia Internet lo son todavía más entre los profesores de menos experiencia (menos de 10 años) que entre los de más experiencia (más de 15 años). Con la variable especialidad se establecen diferencias significativas para el ítem 3 que refleja una actitud escéptica ante el uso de Internet en la enseñanza y solo en la disciplina que hemos denominado científico-técnica.

- La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,01 * La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,05

1) Creo que Internet no tiene mucho que ofrecer a la enseñanza; 2) Internet podría ser útil para la enseñanza pero se ha exagerado su importancia; 3) Aunque tiene posibilidades aún está por ver si Internet traerá consigo beneficios para la enseñanza; 4) Internet ofrece importantes posibilidades, pero desde el punto de vista del tiempo del profesor hay otras prioridades; 5) Internet ofrece importantes posibilidades. Hoy día resulta imprescindible para el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje.

Respecto a las relaciones de las razones para el uso con otras variables como experiencia, sexo y especialidad (tabla 3), hemos encontrado resultados que revelan cuestiones importantes. En general, encontramos diferencias altamente significativas entre los distintos ítems de la dimensión razones con los distintos niveles de experiencia. Todas las respuestas a esta dimensión son significativas al n.c. 0,01 en función de los años de experiencia, excepto la del ítem: «el principal obstáculo para usar Internet en clase es la falta de recursos tecnológicos». Analizando en detalle los resultados, constatamos que cuantos más años de docencia, más acuerdo existe respecto a la falta de experiencia, de preparación, de utilidad, como razones para no usar Internet en clase. Asimismo, son los grupos de más experiencia los que no consideran formativo este recurso para los alumnos, frente a los más jóvenes que sí lo califican de formativo y útil, aunque también señalen la falta de recursos como un obstáculo. Por otra parte, la variable sexo también marca diferencias significativas respecto a las razones sobre el uso de Internet. Son las mujeres las que explican que no utilizan la Red por los argumentos de falta de recursos, falta de experiencia y de preparación, así como por la no utilidad de la Red. Por último, también la especialidad científica establece diferencias significativas (n.c. 0,01) en torno a los ítems de falta de recursos, falta de experiencia y falta de preparación. De esta forma, aunque las especialidades de lengua y humanidades y ciencias sociales son las que están más de acuerdo con la falta de experiencia y de preparación como razones para explicar la no utilización de Internet, en el caso del «principal obstáculo para usar Internet en clase es la falta de recursos tecnológicos» también la especialidad artística lo esgrime como argumento, frente al área científico-tecnológica que está en desacuerdo con esta afirmación.

- La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,01 * La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,05

1) El principal obstáculo para usar Internet en clase es la falta de recursos tecnológicos. 2) El principal obstáculo para usar Internet en clase es mi falta de experiencia. 3) El inconveniente principal para usarlo en mis clases es mi falta de preparación. 4) Considero que este recurso no es útil en mis clases. 5) La principal razón para usar Internet en mis clases es porque lo establece la normativa vigente. 6) Considero que es un recurso formativo para los alumnos.

4.2. Incidencia de las actitudes y razones respecto al uso de Internet sobre las metodologías docentes

A continuación, se expondrán los resultados de los análisis cruzados entre las dimensiones de metodología docentes desarrolladas en clase con los recursos asociados a Internet, actitudes sobre el uso y razones para la utilización. Los datos que se exponen más abajo pretenden estudiar con mayor detalle la relación entre las actitudes y creencias de los profesores del estudio y sus prácticas metodológicas en las aulas.

En primer lugar en la tabla 4 aparecen los resultados de las correlaciones entre la dimensión metodológica (para qué tareas docentes se utilizan los recursos de Internet) y la actitudes que los profesores mantienen. Los resultados no ofrecen dudas: prácticamente todas las correlaciones son significativas al 0,01. Los índices tienen un signo negativo cuando la formulación del ítem de actitudes se hace en ese sentido, lo cual quiere decir que las actitudes negativas correlacionan con la no utilización de Internet para tareas docentes, mientras que las positivas lo hacen con la aplicación de dichas tareas en las prácticas del profesor. Las correlaciones muestran un signo positivo cuando la formulación de los ítems coincide en el sentido positivo, lo cual corrobora la tendencia que acabamos de explicar: actitudes positivas hacia Internet se asocian a la aplicación de los recursos de la Red en las tareas docentes y viceversa. Este patrón general se matiza, comprobando que la actitud es la que marca la metodología a seguir con Internet en el aula, tanto para las que tienen que ver con la presentación y manejo de información, donde se encuentran los mayores efectos significativos (p= .376), como para las metodologías comunicativas y colaborativas, donde se encuentran los menores efectos significativos (p=.169).

- La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,01 (bilateral) * La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,05 (bilateral): 1) Creo que Internet no tiene mucho que ofrecer a la enseñanza; 2) Internet podría ser útil para la enseñanza pero se ha exagerado su importancia; 3) Aunque tiene posibilidades, aún está por ver si Internet traerá consigo beneficios para la enseñanza; 4) Internet ofrece importantes posibilidades, pero desde el punto de vista del tiempo del profesor hay otras prioridades; 5) Internet ofrece importantes posibilidades. Hoy día resulta imprescindible para el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje.

En segundo lugar, en la tabla 5 se recogen los resultados correlacionales obtenidos del análisis de las razones que los profesores sostienen en relación con las metodologías educativas para las que usan Internet. Se puede afirmar que los argumentos con más peso para explicar la utilización o no de la Red para las tareas docentes tienen que ver con la percepción que el profesor tiene de su experiencia, su preparación, de la utilidad de Internet para sus clases y de lo que establece la normativa vigente. De esta forma las correlaciones entre estos ítems que acabamos de nombrar son todas significativas al 0,01 y de orden negativo. Por tanto, los profesores que se perciben con falta de experiencia o falta de preparación son los que menos usan Internet para tareas docentes. Asimismo, los que consideran que el recurso de Internet no es útil para sus clases tampoco lo introducen en su trabajo. Y los que no están de acuerdo con que la principal razón para usar Internet en sus clases sea la normativa vigente, son los que más usan este soporte para tareas docentes. Por otra parte, la falta de recursos como obstáculo para usar Internet en clase correlaciona significativamente prácticamente con todas las tareas docentes, excepción hecha de las tareas de comunicación y colaboración, que tienen un carácter anecdótico en su aplicación. Pero este resultado en relación con el ítem de la falta de recursos, revela que los que más usan Internet para tareas docentes, son también los que más ponen de relieve la falta de recursos. De ahí que no sea la falta de recursos el elemento con más peso para explicar las razones de uso o no uso final de Internet en el trabajo del profesor. Por último, una razón que explica de forma clara la utilización de Internet por parte de los profesores es entender que este recurso tiene un carácter formativo para los alumnos, como se puede comprobar en los índices de correlación que se ofrecen en la tabla 5.

- La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,01 (bilateral) * La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,05 (bilateral)1) El principal obstáculo para usar Internet en clase es la falta de recursos tecnológicos; 2) El principal obstáculo para usar Internet en clase es mi falta de experiencia; 3) El inconveniente principal para usarlo en mis clases es mi falta de preparación; 4) Considero que este recurso no es útil en mis clases; 5) La principal razón para usar Internet en mis clases es porque lo establece la normativa vigente; 6) Considero que es un recurso formativo para los alumnos.

4.3. Repercusión de la formación recibida acerca de Internet sobre las actitudes y razones del uso de este recurso en los profesores

Finalmente en la tabla 6 se recogen los resultados correlacionales entre las actitudes y razones de los profesores y la formación recibida sobre Internet. Al analizar los resultados en estas dimensiones lo que nos resulta más destacado son dos elementos. En primer lugar, respecto de las actitudes, aunque en general ya señalábamos que los profesores parecen compartir actitudes positivas hacia Internet, aquéllos que han recibido formación durante la carrera o a lo largo de su desempeño profesional en los Centros de Formación e Innovación Educativa (CFIE) y otras instituciones, son los que significativamente muestran actitudes más positivas hacia el uso de la Red. En segundo lugar, son estos profesores que han recibido formación, del tipo que sea, los que se atribuyen un mayor grado de competencia digital, puesto que son los que no argumentan que sea la falta de experiencia o de preparación el principal obstáculo para usar Internet en clase y en la mayor parte de los conceptos esta diferencia resulta significativa al n.c. 0,01. Sería muy interesante profundizar en estos datos con objeto de obtener una información más exhaustiva sobre el tipo de formación recibida en cuanto a contenidos y metodologías didácticas utilizadas, ya que parece tratarse de una formación que ha resultado efectiva.

- La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,01 * La correlación es significativa al nivel 0,05

1) Formación inicial: durante la carrera, 2) Formación inicial: máster de especialización; 3) Formación inicial: cursos; 4) Formación continua: cursos del C.F.I.E.; 5) Formación continua: máster de especialización; 6) Formación continua: Academias. 7) Autoaprendizaje.

5. Discusión

A la luz de los datos expuestos podemos afirmar que el perfil de creencias de los profesores de secundaria de nuestro estudio se asienta en dos elementos básicos: por un lado, el valor instructivo que le conceden a los recursos de Internet y, por otro lado, el conocimiento que sobre estos recursos se atribuyen los profesores. Respecto del primer elemento la edad se convierte en un factor diferenciador entre actitudes positivas y negativas, más vinculadas las negativas con edades superiores. En relación con el segundo elemento, el conocimiento de los recursos, la diferencia la marca la edad y el sexo, con una menor atribución de competencia digital en las mujeres y en los grupos de más edad. Por último, la formación, en especial la inicial, pero también la impartida en los Centros de Formación e Innovación Educativa de manera particular, repercute positivamente en la valoración que los profesores hacen de su competencia digital.

Estos datos ratifican lo que otras investigaciones han demostrado, lo cual nos permite hacer hincapié en algunos aspectos con importantes consecuencias para las prácticas de aula.

En primer lugar, parece quedar claro que las actitudes ejercen bastante influencia en la introducción de los recursos de Internet en las prácticas de aula. Aunque las actitudes sean en general positivas, aquellos docentes que consideran que estos recursos no tienen valor instructivo, no los incorporan a sus prácticas y esta relación resulta significativa sobre todo en los grupos de mayor edad, como también se pone de manifiesto en el trabajo de Paraskeva y otros (2007). Pero además de la actitud, la creencia de los profesores en su competencia digital parece explicar también la probabilidad de que utilicen los recursos de la Red en sus prácticas docentes. Y en este caso, las diferencias se deben no sólo a la edad, sino también al sexo de los docentes. Sin embargo, aunque el papel de las creencias sobre la atribución de la propia competencia parece ser determinante en la adopción de los recursos, la formación recibida sobre Internet resulta efectiva para mejorar la percepción de tal competencia digital.

En segundo lugar, estos resultados demuestran que resulta ineludible introducir el tema de las creencias y actitudes dentro de la agenda de investigación sobre incorporación de las TIC a las prácticas docentes y, en particular, de Internet como recurso didáctico. Sería preciso estudiar en profundidad cuáles son las creencias que explican de forma específica la adopción o no de estas innovaciones, cómo se conforman y qué elementos las definen. Además de analizar la formación recibida sobre Internet, contenidos, enfoques instructivos, puesto que es una razón que explica el cambio en la percepción de la competencia profesional en relación con estos recursos. Por último, resulta importante desarrollar líneas de investigación que conecten concepciones pedagógicas de los profesores y creencias sobre TIC en general e Internet en particular, por la vinculación que parece existir entre ambos factores, sin perder de vista cómo todo ello se verifica en los contextos prácticos donde realmente se llevan a cabo los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje.

Apoyos

Esta investigación ha sido realizada gracias a los fondos del proyecto SA060A06 de la Junta de Castilla y León.

Referencias

Aguaded, J.I. & Tirado, R. (2008). Los centros TIC y sus repercusiones didácticas en primaria y secundaria en Andalucía. Educar, 41; 61-90.

Calderhead, J. (1996). Teachers: Beliefs and Knowledge. In Berliner, D. & Calfee, R. (Eds.), Handbook of Edu-cational Psychology. New York: Macmillan; 709-725.

Chan, K-W. & Elliott, R.G. (2004). Relational Analysis of Personal Epistemology and Conceptions about Teaching and Learning. Teacher and Teaching Education, 20 (2004); 817-831.

Ertmer, P.A. (2005). Teacher pedagogical beliefs. The final frontier in our quest for technology integration? Educational Technology Research and Development, 53(4); 25-39.

Fang, Z. (1996). A Review of Research and Teacher Beliefs and Practices. Educational Research, 38 (1); 47-65.

Froufe, S. (2000). Análisis crítico de las actitudes bloqueadoras de la comunicación humana. Comunicar, 14; 97-102.

Groves, M. & Zemel, P. (2000). Instructional technology adoption in higher education: an action research case study. International Journal of Instructional Media, 27 (1); 57-65.

Hinojo, J. & Fernández, F. (2002). Diseño de escala de actitudes para la formación del profesorado en tecno-logías. Comunicar, 19; 120-125.

Kagan, D.M. (1992). Implications of Research on Teacher Belief. Educational Psychologist, 27(1); 65-90.

Koehler, M.J. & Mishra, P. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108; 1.017-1.054.

Lawless, K. & Pellegrino, J. (2007). Professional Development in Integrating Technology into Teaching and Learning: Knowns, Unknowns, and Ways to Pursue Better Questions ans Answers. Review of Educational Research, 77; 575-614.

Lumpe, A.T.; Haney, J.J. & Czerniak, C.M. (2000). Assessing Teachers’ Beliefs about Their Science Teaching Context. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37; 275-292.

Mcgrail, E. (2005). Teachers, Technology and Change: English Teachers’ Perspectives. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13; 5-24.

Mominó, J.M.; Sigales, C. & Meneses, J. (2008). L’escola a la societat xarxa: Internet a l’Educació Primària i Secundària. Barcelona: Ariel y UOC.

Mueller, J.; Wood, E.; Willoughby, T.; Ross, C. & Specht, J. (2008). Identifying Discriminating Variables between Teachers who Fully Integrate Computers and Teachers with Limited Integration, Computers and Education (doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.02.003) (01-07-2011).

Nespor, J. (1987). The Role of Beliefs in the Practice of Teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19; 317-328.

Pajares, M.F. (1992). Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning up a Messy C Construct. Review of Educational Research, 62; 307-332.

Paraskeva, F. & al. (2007). Individual Characteristics and Computer Self-efficacy. Computers & Education (doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2006.10.006) (01-07-2011).

Pozo, J.I. (2000). Concepciones de aprendizaje y cambio educativo. Revista Ensayos y Experiencias, 33; 4-13.

Pozo, Y. & Rodrigo, M.J. (2001). Del cambio de contenido al cambio representacional en el conocimiento conceptual. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 24 (4); 3-22.

Putnam, R., & Borko, H. (1997). Teacher learning: Implications of new views of cognition. In Biddle, B.; Good, T. & Goodson, I. (Eds.). The International Handbook of Teachers and Teaching. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1.223-1.296.

Wozney, L.; Venkatesh, V. & Abrami, P.C. (2006). Implementing Computer Technologies: Teachers’ Perceptions and Practices. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 14; 120-173.

Document information

Published on 29/02/12

Accepted on 29/02/12

Submitted on 29/02/12

Volume 20, Issue 1, 2012

DOI: 10.3916/C38-2012-03-06

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?