(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== The u...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 461084070 to Tobias et al 2015a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 09:47, 28 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

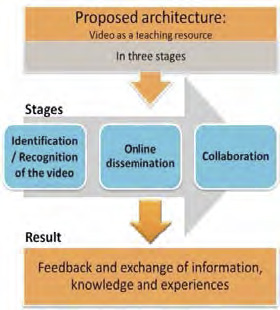

The use of video as a teaching resource stimulates the construction of new knowledge. Although this resource exists in several genres and media, the experience of professionals that use this resource in class is not appreciated. Furthermore, online spaces guiding and supporting the appropriate use of this practice are unavailable. In the online learning field, a proposal has emerged for a repository of short videos aimed at instructing how to use them as a teaching resource in order to stimulate the exchange of ideas and experience (fostering and creating knowledge) in the teaching-learning process, which serves as a resource for professionals in the construction of MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). A three-stage architecture is methodologically proposed: identification/recognition, dissemination and collaboration in the use of videos as a teaching resource supported by an extensive exploratory research, based on existing educational technologies and technological trends for higher education. And this leads to the creation of a repository of Informational Content Recovery in Videos (RECIF), a virtual space for the exchange of experience through videos. We conclude that through methodologies that facilitate the development of innovative processes and products, it is possible to create spaces for virtual or face-to-face motivational classes (MOOCs) thereby completing an interactive and collaborative learning toward stimulation of creativity and dynamism.

1. Introduction

The globalisation tendency stimulates the creation of space among Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to promote partnerships with professors, students, courses and research, further fostering innovation in the Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). The twenty-first century has stimulated in the whole world the creation of collaborative networks as well as federated networks for research and use of these technologies among universities and study centres. According to Dillenbourg and al. (2009), collaboration plays a significant role in knowledge construction. Collaborative learning describes a variety of educational practices in which the interaction among participants is an important factor in the teaching-learning process.

Nowadays, Universities are being reformed due to the incorporation of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), particularly as a consequence of the release and development of Internet 2.0 (Cabero & Marín, 2014; Vázquez-Cano & López, 2014). For this reason, we have experienced a revolution of higher education, an activity that will grow and spread globally as in the case of the MOOC phenomenon (Aguaded & al., 2013; Vizoso, 2013). Distribution of recorded classes and conferences is widespread in Internet; they are disseminated in Platforms such as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) (Cormier, 2008; McAuley & al., 2010) for the purpose of exchanging information and knowledge. The latter is an evolution of the conventional educational environments of Distance Education with two significant characteristics: a) Massiveness, meaning courses for thousands and thousands of people; and b) open: integration with social networks. In summary, MOOCs have been established as a progress in the education and training-related areas (Bouchard, 2011; Aguaded & al., 2013). Thus, MOOCs can be considered as a progress with technological and social inclinations, especially in the higher education sphere toward stimulation oriented to innovation and promotion of massive, open and interactive learning, that is to say, the genesis of collective research (Vázquez-Cano & al., 2014; Vázquez-Cano & López, 2014).

The offer of different courses for professional training of individuals is aimed at achieving the mission of training new generations toward a critical and creative appropriation of learning, which means teaching to learn how to be a citizen able to use the technologies as a means of participation and expression of one´s opinions, knowledge and creativity.

Search for creative interactive and dynamic learning is a reason that motivates teachers to always seek for innovative teaching strategies aimed at attracting attention of students for them to attentively experience their own learning process, the nearest possible to their reality (Eishani & al., 2014). This has led to an initiative to use video as an information strategy, working with all the senses through movement, feeling, text and vision. Videos are part of the so-called digital media dealing with issues and topics, in different forms and styles of messages referring to the main daily issues and situations. Videos, being considered as an informational product, transmit information as text, sound and a succession of images giving the impression of movement. The foregoing aspects of videos are important to create signs, meanings and for development of concepts. The objective is to understand and explain the reality, to create values, desires and fantasies, which constitute subjectivities generated by experiences and expectations.

This study intends to present a digital repository of Informational Content in Video to support, facilitate and gather learning objects for the online teaching-learning process. The project under research is the Platform of Informational Content Recovery in Videos (RECIF in Portuguese), which commenced research in 2007, and the first version of the project was implemented in 2010 by the Research Group on Science, Information and Technology of the Federal University of Paraná. Since its creation, this project consists in identifying and gathering content in Video to be used in the classroom.

2. Use of technology to improve educational practices

During the twenty-first century, schools began incorporating technological resources (Feria & Machuca, 2014) and using them to solve problems during pedagogical practice and in social relations. Since that moment, we can enjoy technological interactivity that motivates professionals to select information and access virtual spaces under a pedagogical and significant perspective oriented to the knowledge exchange culture. Learning through the use of tools that stimulate interactivity, the recreational component could be obtained through online games, networked discussions or forums, virtual research, films, blogs or e-mails, that is, access to virtual learning (Almeida & Freitas, 2012).

Barros (2005) presents a discussion on the use and appropriation of technology by professors in their educational practices, demanding new forms to organise the existing structures or even proposing new ones to better respond to the society´s emerging issues.

«In general terms, it is being introduced a currently emerging new educational paradigm, whose pedagogical dynamics is characterised by a need to develop in each student the practice of advanced skills through the adoption of large units of authentic contents linked to the introduction of a multidisciplinary curriculum; the evaluation of achievement and/or performance; an emphasis to collaborative learning; the position of the teacher as a facilitator; the predominance of heterogeneous groups, the student learning, assuming a connotation of dynamic content exploration, and the adoption of interactive teaching modes» (Means, 1993).

By virtue of the insertion of TIC in education, there is a need to conceptually understand what educational technology is. Bueno (1999: 87) conceptualises technology as «a continuous process through which humanity moulds, modifies and generates its quality of life. The human being is in a constant need of creation and interaction with nature by producing from the most primitive to the most modern instruments, using scientific knowledge to apply the technique, modify and improve the products inherent to the process of interaction of the human being with nature and other human beings».

Technology identifies with a type of culture, which is related to the social, political and economic moment. Significance must be ascribed to the improvement of pedagogical practice (MacPhail & Karp, 2013), in the training of professionals. The teacher must understand technology as an instrument that participates in the construction of a democratic society. Video is the technological proposal discussed in this article toward the appropriation of its potential and its use in the planning, development and application of teaching situations occurring in cyberspace: «Over a century ago, the cinema has fascinated and moved people around the world. Among those persons who regularly went, are going or will go to watch a movie in a dark room, teachers and students are certainly included» (Napolitano, 2006). Napolitano (2006) presents problems in the adaptation and treatment of video as a pedagogical resource, as shown in figure 1, for it is necessary to select the video based on the technical and organisational possibilities of the exhibition, articulation with the content, discussed concepts, general and specific objectives to be achieved. Therefore, the importance of the filmic analysis and semiotics analysis (search for implied meanings) is the video selection. For using this resource, the teacher needs to be organised for selection and schematisation of the scenes addressing the topic of the discipline, time and school work. As a pedagogical strategy, it requires experience from the teacher in the manner of conducting activities according to the public and objective desired in the classroom.

Figure 1: Flowchart showing the selection of a video as a teaching resource. (Based on Napolitano, 2006).

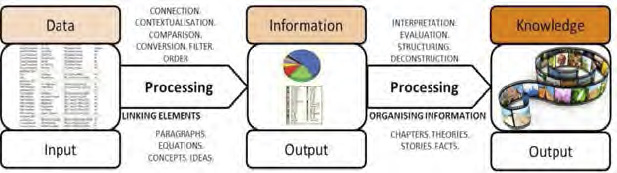

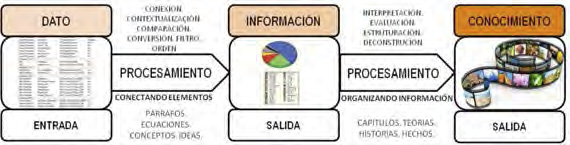

According to Rezende & Abreu (2006), the information becomes «all worked, useful, treated data having an attributed or added significant value with a natural and logical sense for the user of those data». The information is described by Le-Coadic (1996) as knowledge inscribed (engraved) in a written way (printed or numerical), verbal or audio-visual. It is a meaning transmitted to a conscious being through a message inscribed in a space-temporal support: printout, electric signal, sound wave, etc. It is also affirmed that utilising an information product is using such «object» to also obtain an effect that satisfies an information need. This process and connections of data and information are presented in figure 2.

Figure 2: View of RECIF Project under the concepts: data, information and knowledge. (Based on Abreu, 2006; Le-Coadic, 1996).

Teaching with videos requires examining the video content and evaluating its consistency first (figure 2). Consequently, an analysis of semantics and definition of descriptors is required thereby enabling the recovery of information contained in the movie (Chella, 2004). This is also similarly applied to MOOCs (Pappano, 2012; Little, 2013) resulting from conferences and classes taught at institutes. The content analysis, along the sequential study of the video, will allow the search and selective recovery of the information specified by the user.

The principle of semiotics implies an object exploration, and this is solely possible when the concepts of reality and truth are related. However, semiotics (Ranker, 2014) does not directly refer to reality it prefers the analysis through signs and texts (Duarte & Barros, 2005:194)

The use of semiotics in learning means to interpret its flow and, based on the lesson, to identify how the meanings are distributed in and between the modes of representation and communication thereby combining innumerable varieties among teaching, learning, interactions and activities. All this occurs through different means located in different dissemination media (Mavers, 2009; Ranker, 2014). It is worth presenting above the repository project and its dimensions for complementary use in teaching activities.

3. Recovery of filmic informational content

Figure 3 above clearly presents this research methodology, which proposes three stages and shows the explored literature, which supports the architecture proposed intended to use the online filmic resources as a teaching resource.

Figure 3: Architecture of methodology proposed.

In the application of the explored literature study, the first RECIF project version was released in 2010, it consisted in an interface with sections on how to use a video as a teaching resource; it was static, and videos were not shown; for this reason, an interaction between the information presented and the observer´s opinion was not perceived according to the proposal of this research (figure 4: doi.org/tm6).

Offering free and quality information of open access for any person regardless of the country of location constitute aspects that have attracted great interest on MOOCs (Young, 2012; Al-Atabi & DeBoer, 2014) worldwide, besides no enrolment fee for the course in needed (Liyanagunawardena & al., 2013). How this will be achieved in Brazil? Videos examined in the RECIF project are videos of conferences, symposiums, classes and fragments of commercial movies; however, the copyright law permits the teacher to use filmic fragments if intended for teaching practices. Project RECIF freely offers the methodology of use and orientation on the possible specific fragments of scenes for a class with a declared objective of helping in the recreational process of learning a topic.

In RECIF, the use of social networks is emphasised toward consolidation of these learning communities; the platform allows the teacher to share his experience and even comment the application outcome with peers in networks (Facebook, Google+, among others). Collaboration is achieved in the insertion of associates in the use of already renowned technologies (videos) with new ones (open repositories, RECIF).

The new RECIF project interface (goo.gl/th1cMm) released in 2014, intends to implement courses with videos in xMOOC format (figure 4: doi.org/tm6; figure 5: doi.org/tm7).

Besides social networks (Nikou & Bouwman, 2014), people involved in the community may contribute in adding content to exchange information, thematic materials and learning strategies (Méndez-García, 2013).

The first results of this project were presented in two monographs: «Digitalmedia : the role of video as a resource of information in the generation of learning», by Alcides (2009) and «Model proposal for recovery of informational content in movies» by Santos (2009). Subsequently, it was implemented just as a platform by means of start-up scientific and technological studies. It should now be prepared to belong to a federated network, which motivates the breadth of this study.

4. RECIF Project and its dimensions

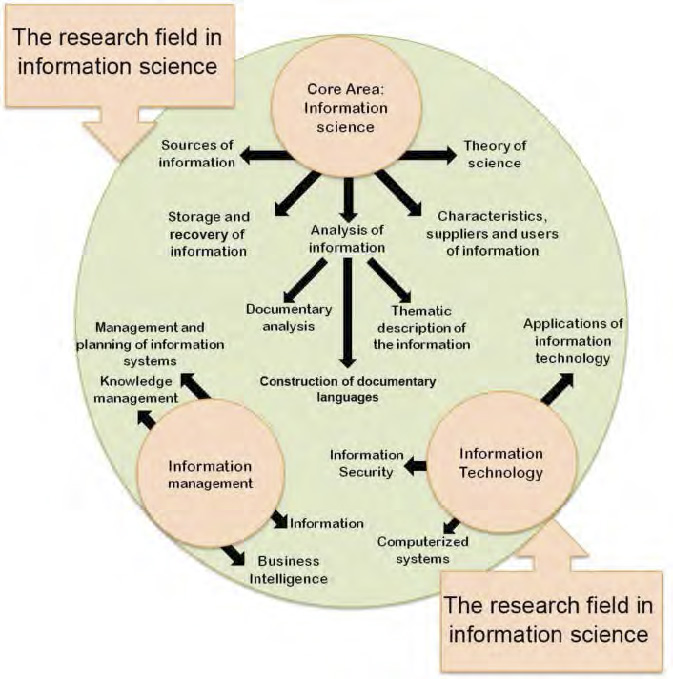

This study includes a proposal for its application in an information system structure gathering film clips. Once these are selected, they are to be used as a teaching-pedagogical strategy to generate learning on a topic. Figure 6 shows this study in the point of view of the information science field.

Figure 6: Analysis of information in the context of the RECIF research (Baptista & al., 2010: 77).

Figure 6 serves to sustain the use of video as a teaching resource in the classroom and, if compared with figure 2, a relationship of the RECIF Project with the «data-information-knowledge» structure can be observed. And in accordance with figure 6, considering the «video» resource as a strategy in the classroom (table 1: doi.org/tm8) is made to illustrate the information presented for it to be understood and assimilated in this project.

Figure 1 provides an analysis conducted on the RECIF project according to information analysis flow proposed by Baptista and al. (2010: 77), as seen in figure 6. The following subsections will analyse the dimensions of RECIF project regarding its characteristics, both: Operational and Strategic.

4.1. RECIF Project Operational Dimension

RECIF project is a learning tool (Kassim & al., 2014) developed to help teachers to make classes dynamic. It involves a databank with descriptions of film fragments that can be used as a teaching resource by teachers who seek to improve the recreational character of their classes through practical examples or, analogies (Santos: 2009). The ways to exchange knowledge through digital media and also the learning theories (Sitti & al., 2013) are constantly transformed. Galan (2003) affirms that online learning is a profession whose own name is unknown (for suffering from an identity crisis) or a thing that becomes something new and better (table 2 doi.org/tm9) summarises the five realities that modify the learning concept, these precepts are confirmed by several authors, among others (Rosenberg, 2005: 5).

Based on the above statement, the RECIF project intends to cover these questions; therefore, it can: filter, catalogue, add, merge and integrate, in an intelligent, reliable and solid manner, movie scenes from different sources of heterogeneous character found at internet. This type of content shall provide a message, analogy or example for learning a discipline.

Rosenberg (2005) confirms that two ways of online learning; online entertainment and knowledge management (Badpa & al., 2013; Ooi, 2014), as a group, can offer better results. The following step is to unite those dimensions with the traditional approaches of learning in the classroom toward a construction of a complete architecture of learning based on technology.

4.2. Conceptual Dimension of RECIF Project

According to Teixeira (1995), the distinction between real and imagined experience «define» us as individuals producing words, senses and meanings. Individuals of time, culture and communication; individuals creating signs, meanings and preparing concepts, seeking to understand and explain the reality in which they live, by creating values, desires and fantasies. This forms the subjectivity of individuals and generates their own experiences and expectations. Based on the above, the RECIF project has been designed for the individual to create knowledge and, at the same time, share that knowledge in the interface.

In the process of conceptual analysis, the RECIF project deals with concepts, definitions, hierarchies and typologies of information. RECIF is a system that summarises the main information of videos so they can be subsequently used as a teaching resource. RECIF intends to make the information available to users with a focus in education. The purpose is to stimulate and facilitate the use of films as a teaching resource by providing the interested party with motivation and interaction in the learning process.

Use of RECIF project is proposed to cause students to search for information by providing a non-linear learning, but composed of concepts, reflexions and analysis. The use of this resource intends to assist the teacher with time and work for what has been taught at the class may be made available in Internet for consultation out of the classroom environment although it can be used again as reinforcement in class.

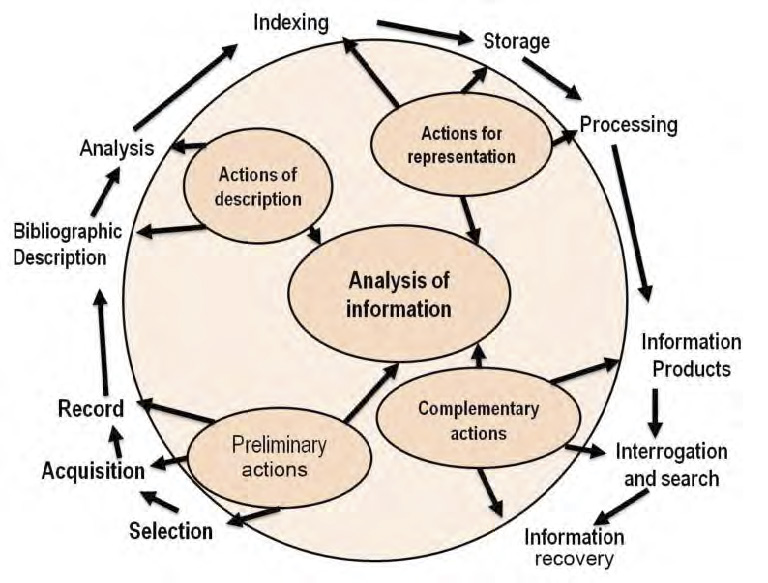

The basis of filmic recovery through content consists in identifying metadata that satisfy the needs of the user. For this reason, the basis of this research is the analysis of informational content in filmic scenes toward its accessibility as digital repository. Figure 7 is an adaptation to represent the descriptors of the content management process inherent to the RECIF Platform (Santos, 2009)

Figure 7: Analysis of information in the context of the information sciences research. (Based on Baptista & al., 2010: 72).

Figure 7 describes the content management process in the RECIF Project; there are four actions to be taken for information analysis: description; representation, preliminary and complementary actions; we can start from any of them according to the topic we want to find or catalogue, related examples:

• If we lack a video for a specific class, based on figure 7, we will identify the action area; and we then note that we must commence from the «preliminary actions» and, in this manner, we will commence searching a video appropriate for the selected topic; and we can pass from this action analysis area to the next ones, according to figure 7 proposed by the authors.

• If we have a video, but we ignore how it must be catalogued, then, we take the «creation actions» by making an analysis of the video, and then, we continue to the «representation actions» area, and we index the content found.

Six theories were proposed in the technology field (figure 3: doi.org/tnb) over the last years. And from the traditional learning theories presented in figure 4 (doi.org/tnc), it could be said that the RECIF project is mainly focused in the theories of the humanistic teaching approaches, that is, the significant learning (the same line of e-learning). In the same manner, significant learning provides relevance to the internal learning variables of each individual and human conduct is considered as a whole. This can be reflected in the RECIF project for the resources are made available and found according to the needs of the Platform users.

For Texeira & al. (2014), the principal learning theories are divided according to the main learning needs: Associationist and Mediational (figure 4).

Implementation of the RECIF project is focused on the type of associationist theories for they mainly seek the reasoning of the individual (the project objective), either an experience or learning through the filmic scenes provided.

4.3. Strategic Dimension of RECIF Project

Spaces in the twenty-first century for exchanging research and materials applied to education fostered the development of repositories of the most different fields for Learning Objects, most of which are available for free.

However, diversification of information is small, especially when evaluating the contents and objects intended for higher education. Given the need to extend opportunities among researchers of this topic, virtual spaces should be identified (Hernández & al., 2014) for exchange of experience and innovation, applicable to higher education based on technologies thereby obtaining an interactive and collaborative learning tool (Leinonen & Durall, 2014).

Information analysis with an emphasis in the strategic dimension has been applied in security issues in the content shared with facility and access to federated platforms with a sole identity and the extension of use of the learning objects developed. Dissemination of federated content implies different safety questions; for this reason, one must belong to web sites of reliable federated content.

The idea of dissemination of projects such as RECIF, as a product, is intended to improve and implant the platform to share experience.

The concept is based on three fundamental ideas:

• It is based on federated (interconnected) networks.

• The dissemination takes place through Internet technology in a computer focused on the user.

• The approach is learning, in the widest sense.

Use of Internet allows the up-dating, dissemination and virtually instantaneous distribution of the information. It is noted that people have less and less time to learn; and for this reason they need to learn at a faster rate. And the digital repositories, such as the RECIF project, offer to the end user the means to learn rapidly and to share at the same time. Future perspectives are for spaces to become collaborative with a possibility of connection with other associated institutions in any part of the world; in this manner a filmic base is offered for the use of practices in the classroom for higher education.

5. Final considerations

As it has been expressed at the beginning of this research, it is concluded that the expected result, that is, sharing of knowledge, information and experience among the users of the proposed architecture, is achieved by means of the identification of the correct material concurrently with its online distribution. In this manner, when video is used, youngsters reflect on the reality experienced and express themselves through language, by handling the signs presented in the selected video and processing information. In the semiotics process, information is used to make generalisations and suppositions. Teachers relate the theory to be transmitted to an analogy through video and the aspects observed in each student as for existences (facts, ideas and sensitivities) which, when been assimilated, generate information and individual knowledge.

New technologies provide applications that create, when used in school learning, a new model of materials for the teaching-learning process. Features provided in federated platforms can work as a «class after a class» in a virtual space where students and teacher get in contact. They also provide a new sense to teaching resources. Federated platforms offer an exchange of opinions where students and teachers can also create their own space related to educational topics. Web sites such as Youtube may help in sharing information taught in class and the opinions of teachers or students on a topic.

This work is intended to present the RECIF project and make it available in a Federated System, which possesses filmic informational content with pedagogical objectives. The project demands an analysis of filmic scenes along with semiotics for extraction of information and implied meanings, and the subsequent organization of that knowledge. In accordance with the proposal in the objective of this work, it was possible to explore the theories implied in the RECIF project, and show how the analysis of its information is conducted in a federated platform intended to recover informational content suitable for learning purposes.

Techniques used for information and knowledge organisation were investigated in the RECIF project (filmic scene as an informational product), content object and the use of video as a digital repository. The project operation was specifically described along with its operational and conceptual scopes. A description was made on how to conduct an information analysis including its relationship with the learning theories that support the project as a method that well managed could become an effective learning tool.

In this study, it is noted that the teaching-learning process is effective when well managed by technological tools, in the special case of federated platforms, offering special resources in the teaching field to contribute to the development of the knowledge of the user, either student or teacher. Therefore, it can also create knowledge by fostering learning in class.

Online technologies, for being used as tools of constructivist knowledge, create an experience on traditional learning, which results to be different in the teaching-learning process, with better results among students. For they stimulate their way of learning; therefore, they learn better and construct their own knowledge.

For this reason, this research contributes with the proposal of an architecture that stimulates teachers, students and researchers in the recovery/collaboration of learning objects. Besides, it can be implemented at a low cost because of its freeware application.

References

Aguaded, J.I., Vázquez-Cano, E. & Sevillano, M.L. (2013). MOOCs, ¿turbocapitalismo de redes o altruismo educativo? En Scopeo Informe, 2: MOOC: Estado de la situación actual, posibilidades, retos y futuro. (pp. 74-90). Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca Servicio de Innovación y Producción Digital. (goo.gl/slqguU) (22-06-2014).

Al-Atabi, M. & DeBoer, J. (2014). Teaching Entrepreneurship Using Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). Technovation, 34, 4, 261-264. (doi.org/tmk).

Alcides, R. (2009). Mídia digital: o papel do filme de animação como recurso de informação na geração da aprendizagem. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso, UFPR, Curitiba. (goo.gl/Qfqy8Y) (10-07-2014).

Almeida, M.G. & Freitas, M.C.D. (Org.). (2012). A Escola no Século XXI, 2: Docentes e Discentes na Sociedade da Informação. Rio de Janeiro: Brasport.

Badpa, A., Yavar, B., Shakiba, M. & Singh M.J. (2013). Effects of Knowledge Management System in Disaster Management through RFID Technology Realization. Procedia Technology, 11, 785-793. (doi.org/tmm).

Baptista, D.M., Araújo JR., R.H. & Carlan, E. (2010). O escopo da análise de informação. In: J. Robredo, M.J. Bräscher & M. Bräscher (Orgs.), Passeios no bosque da informação: estudos sobre representação e organização do informação e do conhecimento. Brasília DF: IBICIT. (goo.gl/kt4X56) (02-01-2014).

Barros, N.V. (2005). Curso: Capacitação para Conselhos Tutelares (Projeto SIPIA) ministrado na Faculdade de Administração-Niterói /UFF.

Belloni, M.L. (1998). Tecnologia e formação de professores: rumo a uma pedagogia pós-moderna? Educação e Sociedade, 19, 65, 143-162. (doi.org/d38f7q).

Bévort, E. & Belloni, M. (2009). Mídia-educação: conceitos, história e perspectivas. Educación Social, 30, 109, 1081-1102. (doi.org/fw7jm7).

Bouchard, P. (2011). Network Promises and their Implications. In The Impact of Social Networks on Teaching and Learning. RUSC, 8,1, 288-302. (goo.gl/Y7TSZK) (23-06-2014).

Bueno, N.L. (1999). O desafio da formação do educador para o ensino fundamental no contexto da educação tecnológica. Curitiba: Dissertação de Mestrado, PPGTE-CEFET/PR.

Cabero, J. & Marín, V. (2014). Posibilidades educativas de las redes sociales y el trabajo en grupo. Percepciones de los alumnos universitarios. Comunicar, 42, 165-172. (doi.org/tmt).

Chella, M.T. (2004). Sistema para Classificação e Recuperação de Conteúdo Multimídia Baseado no Padrão MPEG, 7. São Paulo: UNICAMP.

Cormier, D. (2008). The CCK08 MOOC - Connectivism course, 1/4 way. Dave’s Educational Blog. (goo.gl/tskvev) (22-06-2014).

Davies, D., Jindal-Snape, D., Collier, C., Digby, R., Hay, P. & Howe, A. (2013). Creative Learning Environments in Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8, 80-91 (doi.org/tmn).

Dillenbourg, P., Järvelä, S.Y. & Fischer, F. (2009). The Evolution of Research on Computer-supported Collaborative Learning. In Technology-enhanced Learning, Springer Netherlands, 3-19.

Duarte, J. & Barros, A. (Eds.) (2005). Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa em comunicação. IASBECK, Luiz Carlos Assis. São Paulo: Atlas. Eishani, K.A., Saa’d, E.A. & Nami, Y. (2014). The Relationship between Learning Styles and Creativity. Procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 52-55 (doi.org/tms).

Feria, L.B. & Machuca, P. (2014). The Digital Library of Iberoamerica and the Caribbean: Humanizing Technological Resources. The International Information & Library Review, 36, 3, 177-183 (doi.org/cc4p57).

Galagan, P. (2003). The Future of the Profession Formerly known as Training. T&D Magazine, 57, 12, 26-38.

Hernández, N., González, M. & Muñoz, P.C. (2014). La planificación del aprendizaje colaborativo en entornos virtuales. Comunicar, 42, 25-33. (doi.org/tmp).

Kassim, H., Nicholas, H. & Ng, W. (2014). Using a Multimedia Learning Tool to Improve Creative Performance. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 13, 9-19 (doi.org/tmr).

Le-Coadic, Y.F. (1996). A ciência da informação. Brasília, DF: Briquet de Lemos.

Leinonen, T. & Durall, E. (2014). Pensamiento de diseño y aprendizaje colaborativo. Comunicar, 42, 107-116. (doi.org/tmq).

Little, G. (2013). Massively Open? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39, 3, 308-309. (doi.org/tmv).

Liyanagunawardena, T., Adams, A. & Williams, S. (2013). MOOCs: A Systematic Study of the Published Literature 2008-12. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14, 3, 202-227. (doi.org/tmw).

MacPhail, A., Tannehill, D. & Karp, G.G. (2013). Preparing Physical Education Preservice Teachers to Design Instructionally Aligned Lessons through Constructivist Pedagogical Practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 33, 100-112. (doi.org/tmx).

Mavers, D. (2009). Student Text-making as Semiotic Work. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 9, 2, 141-155. (doi.org/bwbn34).

McAuley, A., Stewart, B., Siemens, G. & Cormier, D. (2010). The MOOC Model for Digital Practice. (goo.gl/ljmvEl) (23-06-2014).

Means, B. (1993). Using Technology to Support Education Reform. Education Development Corporation. U.S. Department of Education. September. (goo.gl/SQ9uaa) (30-04-2014).

Méndez García, C. (2013). Diseño e implementación de cursos abiertos masivos en línea (MOOC): expectativas y consideraciones prácticas. RED, 39, 1-19. (goo.gl/pHHweM) (11-07-2014).

Napolitano, M. (2006). Como usar o cinema na sala de aula. 4. Ed. São Paulo: Contexto.

Nikou, S. & Bouwman, H. (2014). Ubiquitous Use of Mobile Social Network Services. Telematics and Informatics, 31, 3, 422-433 (doi.org/tmz).

Ooi, Keng-Boon. (2014). TQM: A Facilitator to Enhance Knowledge Management? A Structural Analysis. Expert Systems with Applications, 41, 11, 5167-5179. (doi.org/tm2).

Pappano, L. (2012). The year of the MOOC.The New York Times. (goo.gl/3P2yPG) (22-06-2014).

Ranker, J. (2014). The Emergence of Semiotic Resource Complexes in the Composing Processes of Young Students in a Literacy Classroom Context. Linguistics and Education, 25, 129-144. (doi.org/tm3).

Rezende, D.A. & Abreu, A.F. (2006). Tecnologia da informação aplicada a sistemas de informação empresarial: o papel estratégico da informação e dos sistemas de informação nas empresas. São Paulo: Atlas.

Rosenberg, M.J. (2005). Beyond e-Learning: Approaches and Technologies to Enhance Organizational Knowledge, Learning and Performance. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Santos L.R.N. (2009). Proposta de modelagem para recuperação de conteúdo informacional em filmes. Monografia de conclusão de curso em Gestão da Informação. Curitiba: UFPR. (goo.gl/Pa4PZk)(10-07-2014).

Sitti, S., Sopeerak, S. & Sompong, N. (2013). Development of Instructional Model Based on Connectivism Learning Theory to Enhance Problem-solving Skill in ICT for Daily Life of Higher Education Students. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103, 315-322. (doi.org/tm5).

Teixeira, C.E.J. (1995). A Ludicidade na Escola. São Paulo: Loyola.

Texeira, A., Ferreira, E. & Sousa, E. (2014). Preparatório para o concurso da SEMED. Secretaria Municipal de Educação. , Brasil: Governo do Manaus.

Vázquez-Cano, E. & López, M.E. (2014). Los MOOC y la educación superior: la expansión del conocimiento. Profesorado, 18, 1, 1-10.

Vázquez-Cano, E., Sirignano, F., López M.E. & Román, P. (2014). La globalización del conocimiento: Los Moocs y sus recursos. II Congreso Virtual Internacional sobre Innovación Pedagógica y Praxis Educativa. Sevilla, 26-28 de marzo.

Vizoso, C.M (2013). ¿Serán los COMA (MOOC), el futuro del e-learning y el punto de inflexión del sistema educativo actual? Boletín SCOPEO, 79. (goo.gl/NjoLRA) (22-06-2014).

Young, J. (2012). Inside the Coursera Contract: How an Upstart Company Might Profit from Free Courses. The Chronicle of Higher Education. (goo.gl/xxkd5S) (22-06-2014).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El uso de vídeos como recurso didáctico estimula la construcción de nuevo conocimiento. A pesar de la existencia de este recurso en diversos géneros y medios, no se valora la experiencia de los profesionales que lo aprovechan en clase y además no se cuenta con espacios online que orienten y apoyen el uso apropiado de esta práctica. En el ámbito del aprendizaje online, surge la propuesta de un repositorio de vídeos de corta duración, con el objetivo de orientar acerca de su uso como recurso didáctico, a fin de incentivar un intercambio de ideas y experiencias (fomentar y crear conocimiento), en el proceso enseñanza-aprendizaje, sirviendo esto como recurso para profesionales en la construcción de los MOOC (Massive Open Online Courses). Metodológicamente se propone una arquitectura en tres etapas: identificación/reconocimiento, diseminación y colaboración, para el uso de vídeos como recurso didáctico, sustentándose en una extensa investigación exploratoria, basándose en las tecnologías educativas existentes y tendencias tecnológicas para la educación superior. El resultado es la creación de un repositorio de Recuperación de Contenido de Información en Vídeos (RECIF), un espacio virtual de intercambio de experiencias por medio de vídeos. Se concluye que por medio de metodologías que faciliten el desarrollo de procesos y productos innovadores, se pueden crear espacios de clases motivadoras, virtuales o presenciales, que completen un aprendizaje interactivo y colaborativo, estimulando la creatividad y el dinamismo.

1. Introducción

La tendencia de la globalización motiva la creación de un espacio entre las instituciones de estudio superior para promover asociaciones entre profesores, alumnos, cursos e investigaciones. Además del fomento de la innovación en las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC). El siglo XXI ha estimulado mundialmente la creación de redes de colaboración, así como también federadas, para la investigación y uso de las tecnologías entre las universidades y centros de estudio. De acuerdo con Dillenbourg y otros (2009), la colaboración tiene un papel importante en la construcción del conocimiento. El aprendizaje colaborativo describe una variedad de prácticas educativas entre las cuales las interacciones entre los participantes constituyen un factor importante en el proceso enseñanzaaprendizaje.

En la actualidad las universidades se están reformando debido a la incorporación de las tecnologías de la información (TIC), particularmente a causa de la aparición y desarrollo de Internet 2.0 (Cabero & Marín, 2014; VázquezCano & López, 2014). De esta forma, hemos tenido una revolución sobre la enseñanza superior, una actividad que deberá crecer y diseminarse globalmente, como es el fenómeno de los MOOC (Aguaded & al., 2013; Vizoso, 2013). Crece en la Red la distribución de clases y conferencias grabadas, diseminadas en Plataformas como pueden ser los «Massive Open Online Courses» (MOOC) (Cormier, 2008; McAuley & al., 2010), que tienen como propósito el intercambio de información y conocimiento. Estos últimos son una evolución de los ambientes educativos convencionales de educación a distancia, con dos características importantes: a) la «masividad», es decir, cursos que se ofrecen a millares y millares de personas; y b) abierto: integración con las redes sociales. En resumen, los MOOC se han establecido como un progreso en el área educativa y formativa (Bouchard, 2011; Aguaded & al., 2013). De esta manera, se puede considerar a los MOOC como un progreso de tendencia tecnológica y social, especialmente en el panorama del estudio superior para la estimulación orientada a la innovación y promoción del aprendizaje en masa, abierta e interactivamente, es decir la génesis de la investigación colectiva (VázquezCano & al., 2014; VázquezCano & López, 2014).

La oferta de diferentes cursos ofrecidos para la formación profesional de individuos es dirigida para cumplir con la misión de formar las nuevas generaciones, para que así cumplan con una apropiación crítica y creativa de aprendizaje, lo que significa enseñar a aprender, a ser un ciudadano capaz de usar las tecnologías como medios de participación y expresión de sus propias opiniones, saberes y creatividad (Belloni, 1998; Bévort & Belloni, 2009; Davies & al., 2013).

La búsqueda del aprendizaje creativo, interactivo y dinámico es una razón que motiva a los profesores a procurar siempre estrategias didácticas innovadoras con la intención de atraer la atención del estudiante para la vivencia de su propio aprendizaje de un modo atento y lo más próximo posible de su realidad (Eishani & al., 2014). Por ello, destaca la iniciativa del uso del vídeo como una estrategia de la información, que trabaja con todos los sentidos por el movimiento, sentimiento, texto y visión. Los vídeos forman parte de los llamados medios digitales, que trabajan cuestiones o temáticas, con diferentes formas y estilos de mensajes, aludiendo a los principales conflictos, así como a situaciones que ocurren diariamente. Los vídeos, considerados como un producto informacional, transmiten la información en forma de texto, sonido y sucesión de imágenes que dan la impresión de movimiento. Los anteriores aspectos del vídeo son importantes para la creación de signos, significados y para la elaboración de conceptos. Lo que se busca es comprender y explicar la realidad, crear valores, deseos y fantasías, que constituyen las subjetividades generadas por experiencias y expectativas.

Este estudio pretende presentar un repositorio digital de contenido informacional en vídeos para apoyar, facilitar y reunir objetos de aprendizaje destinados al proceso enseñanzaaprendizaje online. El proyecto investigado es la Plataforma de Recuperación de Contenido Informacional en Vídeos (RECIF en portugués), en 2007 fue el inicio de sus investigaciones y la primera versión del proyecto fue implementada en 2010 por el Grupo de Investigación en Ciencia, Información y Tecnología de la Universidad Federal de Paraná. Este proyecto consiste, desde su creación, en la identificación y recopilación de contenido en vídeos para su uso en clase.

2. Uso de la tecnología para la mejora de las prácticas educativas

En el siglo XXI, la escuela pasa a incorporar recursos tecnológicos (Feria & Machuca, 2014) y usarlos para la superación de problemas en la práctica pedagógica, así como en las relaciones sociales. Desde entonces se puede disfrutar de la interactividad tecnológica, que motiva a los profesionales hacia la selección de información y el acceso a espacios virtuales, bajo una perspectiva pedagógica y significativa centrada en la cultura del intercambio de conocimiento. Aprender con el uso de herramientas que estimulan la interactividad, lo lúdico, puede venir por medio de juegos online, discusiones en red o foros, investigaciones virtuales, películas, blogs o emails, esto es, acceso al aprendizaje virtual (Almeida & Freitas, 2012).

Barros (2005) plantea una discusión sobre el uso y apropiación de la tecnología por los profesores en sus prácticas educativas, exigiendo formas nuevas de organizar las estructuras ya existentes, o incluso, proponer nuevas, que mejor respondan a las situaciones emergentes de la sociedad.

«De manera general se presenta lo que actualmente está emergiendo como un nuevo paradigma educativo, cuya dinámica pedagógica se caracteriza por la necesidad de desarrollar en cada estudiante práctica de habilidades avanzadas, por medio de la adopción de largas unidades de contenidos auténticos, unidos por la introducción del currículo multidisciplinar, por la evaluación basada en el desempeño y/o rendimiento, por el énfasis en el aprendizaje colaborativo, en la postura del profesor como facilitador, por la predominancia de agrupamientos heterogéneos, por el aprendizaje estudiantil, asumiendo una connotación de exploración de contenidos dinámicos y por la adopción de modos de instrucción interactivos» (Means, 1993).

Con la inserción de las TIC en la educación es necesario entender conceptualmente lo que es tecnología educativa. Bueno (1999: 87) conceptúa tecnología, siendo: «un proceso continuo a través del cual la humanidad moldea, modifica y genera su calidad de vida. Hay una constante necesidad del ser humano de crear e interactuar con la naturaleza, produciendo instrumentos desde los más primitivos hasta los más modernos, valiéndose de un conocimiento científico para aplicar la técnica, modificar y mejorar los productos oriundos del proceso de interacción de este con la naturaleza y con los demás seres humanos».

La tecnología identifica un tipo de cultura, la cual está relacionada con el momento social, político y económico. Se debe dar importancia al mejoramiento de la práctica pedagógica (MacPhail & Karp, 2013), en la formación de profesionales. Es necesario que el profesor entienda la tecnología como un instrumento de intervención en la construcción de la sociedad democrática. El vídeo es la propuesta tecnológica discutida en este artículo, para apropiarse de su potencial y utilizarlo en el planeamiento, desarrollo y aplicación de situaciones didácticas ambientadas en el ciberespacio: «Hace más de un siglo que el cine encanta y conmueve a las personas en todo el mundo. De entre estas personas que regularmente fueron, van e irán a ver películas a una sala oscura, ciertamente están incluidos profesores y alumnos» (Napolitano, 2006). Este autor presenta la problemática de la adecuación y abordaje del vídeo como recurso pedagógico, como se muestra en la figura 1, pues se hace necesario escoger el vídeo considerando las posibilidades técnicas y organizativas en la exhibición, la articulación con el contenido, los conceptos discutidos, los objetivos generales y específicos a ser alcanzados. Por lo tanto, destaca la importancia del análisis fílmico y análisis de la semiótica (búsqueda por los significados implícitos), en la selección del vídeo. Para la utilización de este recurso el profesor necesita organizarse para la selección y la esquematización de las escenas que atiendan la temática de la disciplina, el tiempo y el trabajo escolar. Como estrategia pedagógica requiere experiencia del profesor en la manera de conducir las actividades en función del público y objetivo deseado en la clase.

Figura 1: Diagrama de flujo que muestra la selección de un vídeo como recurso didáctico (basada en Napolitano, 2006).

Para Rezende y Abreu (2006), la información pasa a ser «todo dato trabajado, útil, tratado, con valor significativo atribuido o agregado a él y con un sentido natural y lógico para quien la usa». La información viene descrita por LeCoadic (1996) como conocimiento inscrito (grabado) bajo una forma escrita (impresa o numérica), oral o audiovisual. Es un significado transmitido a un ser consciente por medio de un mensaje inscrito en un soporte espaciotemporal: impresión, señal eléctrica, onda sonora, etc. Además afirma que utilizar un producto de información es emplear tal «objeto» para obtener, igualmente, un efecto que satisfaga una necesidad de información. Este proceso y sus conexiones de datos e informaciones son presentados en la figura 2.

Figura 2: Vista del Proyecto RECIF desde los conceptos: dato, información y conocimiento (basada en Abreu, 2006 y LeCoadic, 1996.

La enseñanza con vídeo requiere que sea examinado su contenido y evaluar su consistencia primeramente (figura 2). Consecuentemente se requiere un análisis semántico y de definición de los descriptores, posibilitando la recuperación de las informaciones contenidas en el filme (Chella, 2004), de manera semejante con los MOOC (Pappano, 2012; Little, 2013), resultantes de conferencias y clases impartidas en los institutos. El análisis de contenido, a lo largo del estudio secuencial del vídeo, permitirá la búsqueda y recuperación selectiva de información especificada por el usuario.

El principio de la semiótica implica una exploración del objeto, lo que solamente es posible cuando se relacionan los conceptos de la realidad y la verdad. Sin embargo, la semiótica (Ranker, 2014) no se refiere directamente a la realidad, ella prefiere el análisis por medio de signos y de textos (Duarte & Barros, 2005: 194).

El uso de la semiótica en el aprendizaje significa interpretar su flujo, y partir de la lección, identificar como los significados son distribuidos dentro y entre los modos de representación y comunicación, y así combinar innumerables variaciones entre enseñanza, aprendizaje, interacciones y actividades, por medio de diferentes medios localizados en diferentes señales de exposición (Mavers, 2009; Ranker, 2014). Cabe presentar a continuación el proyecto del repositorio y sus dimensiones para uso complementario en las actividades de enseñanza.

3. Recuperación de contenido informacional fílmico

Para presentar de forma clara la metodología de esta investigación, se muestra a continuación la figura 3, que propone tres etapas, mostrando la literatura explorada que sustenta la propuesta de la arquitectura que tiene como objetivo la disposición de recursos fílmicos online como recurso didáctico.

Figura 3: Arquitectura de la metodología propuesta.

En la aplicación de la literatura explorada, se lanzó la primera versión del Proyecto RECIF en 2010, que consistía en una interfaz con secciones sobre cómo usar un vídeo como recurso didáctico. Era estática y los vídeos no eran mostrados, por lo que no se podía apreciar una interacción entre la información presentada y la opinión del espectador, de acuerdo con la propuesta de esta investigación (ver figura 4 y las próximas en el repositorio académico Figshare: doi.org/tm6).

El ofrecimiento de información gratuita, de calidad y de libre acceso a cualquier persona sin importar el país en el cual se encuentre, son aspectos que han atraído gran interés (Young, 2012; AlAtabi & DeBoer, 2014) a nivel mundial, además de no tener la necesidad de hacer ningún pago por inscripciones a los cursos (Liyanagunawardena & al., 2013). ¿Cómo lograr esto en Brasil? Los vídeos estudiados en el proyecto RECIF son vídeos de conferencias, simposios, clases y fragmentos de películas comerciales, pero la ley de derechos permite que el profesor haga uso de fragmentos fílmicos si son destinados a prácticas didácticas. El proyecto RECIF ofrece libremente la metodología de uso y una orientación de los posibles fragmentos o escenas específicas para una clase con el objetivo declarado de ayudar en el proceso de enseñanza lúdica de una temática.

En RECIF, se hace énfasis en el uso de las redes sociales para que consoliden estas comunidades de aprendizaje. La plataforma permite al profesor compartir su experiencia e incluso comentar los resultados de su aplicación con pares en redes (Facebook, Google+, entre otros), logrando colaborar en la inserción de los asociados en el uso de las tecnologías ya consagradas (vídeos) con las nuevas (repositorios abiertos, RECIF).

La nueva interfaz del proyecto RECIF (goo.gl/th1cMm) lanzada en 2014, trata de implementar cursos a partir de los vídeos en el formato xMOOC (figura 4: doi.org/tm6; figura 5: doi.org/tm7).

Además de las redes sociales (Nikou & Bouwman, 2014), los implicados en la comunidad pueden contribuir en la agregación de contenidos para el intercambio de información, materiales temáticos y estrategias de aprendizaje (MéndezGarcía, 2013).

Este proyecto tuvo sus primeros resultados presentados en dos monografías: «Medio digital: el papel del vídeo animado como recurso de información en la generación de aprendizaje», por Alcides (2009) y «Propuesta de modelado para recuperación de contenido informacional en filmes» por Santos (2009). Posteriormente fue implantado al igual que una plataforma por medio de estudios de iniciación científica y tecnológica. Cabe ahora prepararla para que pertenezca a una red federada, razón que motiva la amplitud de este estudio.

4. El proyecto RECIF y sus dimensiones

Este estudio abarca la propuesta de aplicarse sobre la estructura de un sistema de información que reúne cortos fílmicos. Y una vez seleccionados serán utilizados como estrategia didácticopedagógica, para la generación de aprendizaje sobre un tema. La figura 6 muestra este estudio desde la óptica del campo de la ciencia de la información.

Figura 6: El análisis de la información en el contexto de la investigación RECIF (Baptista & al., 2010: 77).

La figura 6 viene a sustentar el uso del vídeo como recurso didáctico en las aulas, si bien es comparada con la figura 2 donde puede apreciarse una relación del proyecto RECIF con la estructura «datoinformaciónconocimiento». Y de acuerdo con la figura 6, visualizando el recurso «vídeo» como estrategia en el aula, se realiza el gráfico 1 (doi.org/tm8) para ejemplificar la información presentada, de manera que sea comprendida y asimilada en este proyecto.

La figura 1 plasma un análisis realizado del proyecto RECIF de acuerdo al flujo del análisis de la información propuesto por Baptista y otros (2010: 77), igual que vimos en la figura 6. En las próximas subsecciones serán analizadas las dimensiones del proyecto RECIF en relación a sus características: operacional, conceptual y estratégica.

4.1. Dimensión operacional del proyecto RECIF

El proyecto RECIF es una herramienta de aprendizaje (Kassim & al., 2014), desarrollada para auxiliar al profesor en el dinamismo de sus clases. Se trata de un banco de datos con descripciones sobre fragmentos fílmicos animados, que pueden ser utilizados como recurso didáctico por docentes que buscan incrementar el carácter recreativo en sus clases mediante ejemplos prácticos o bien, analogías (Santos, 2009). Las maneras de intercambio de conocimiento mediante medios digitales, así como las teorías de aprendizaje (Sitti & al., 2013), están en constantes transformaciones. Galagan (2003) afirma que el aprendizaje online es una profesión donde no se sabe cuál es su propio nombre (al tener una crisis de identidad), o de una cosa que se transforma en algo nuevo y mejor. La figura 2 (doi.org/tm9) resume las cinco realidades que vienen modificando el concepto de aprendizaje, cuyos preceptos son aseverados por varios autores (Rosenberg, 2005: 5).

Con base a lo mencionado anteriormente, el proyecto RECIF trata de abarcar estas cuestiones siendo capaz de filtrar, catalogar, agregar, fusionar e integrar de forma inteligente, fiable y robusta contenidos de escenas de películas, provenientes de diversas fuentes de naturaleza heterogénea encontradas en Internet. Este tipo de contenido proporcionará un mensaje, analogía o ejemplo para el aprendizaje en una disciplina.

Rosenberg (2005) señala dos formas de aprendizaje online: el entrenamiento online y la gestión de conocimiento (Badpa & al., 2013; Ooi, 2014), que en conjunto pueden ofrecer mejores resultados. El paso siguiente es unir estas dimensiones con los enfoques tradicionales del aprendizaje en el aula para la construcción de una arquitectura completa del aprendizaje basado en la tecnología.

4.2. Dimensión conceptual del proyecto RECIF

De acuerdo con Teixeira (1995), la distinción entre lo vivido y lo imaginado nos «define» como individuos productores de palabras, sentidos y significados. Individuos de tiempo, de la cultura y de la comunicación. Creando signos, significados y elaborando conceptos, buscando comprender y explicar la realidad en la cual se vive, creando también valores, deseos y fantasías. Esto es lo que forma la subjetividad de los individuos y genera sus propias experiencias y expectativas. Conforme a lo anteriormente expresado, el proyecto RECIF se ha diseñado para que el individuo cree conocimiento y al mismo tiempo lo comparta en la interfaz.

El proyecto RECIF, en el proceso de análisis conceptual trata de conceptos, definiciones, jerarquías y tipologías de la información, es un sistema que resume la información principal de vídeos para que después puedan ser usados como recurso didáctico. RECIF pretende poner a disposición de los usuarios la información enfocada a la educación. El propósito es estimular y facilitar el uso de filmes como recurso didáctico, proporcionando al interesado motivación e interacción en el aprendizaje.

La propuesta de la utilización del proyecto RECIF es provocar que los alumnos busquen información, proporcionando un aprendizaje no lineal, pero compuesto de conceptos, reflexiones y análisis. La utilización de este recurso pretende ayudar al profesor en cuanto a tiempo y trabajo, ya que lo visto en clase podrá estar disponible en Internet para consulta fuera del ambiente de clase, aunque también pueda ser usado nuevamente en clase como refuerzo.

La base de recuperación fílmica por medio de contenido consiste en la identificación de metadatos que atiendan la necesidad del usuario. Es por eso que esta investigación se basa en el análisis del contenido informacional en escenas fílmicas para su accesibilidad como repositorio digital. La figura 7 es una adaptación para representar los descriptores del proceso de gestión de contenido inherente a la Plataforma RECIF (Santos, 2009).

Figura 7: El análisis de la información en el contexto de la investigación sobre ciencias de la información (basada en Baptista y otros, 2010: 72).

La figura 7 describe como es el proceso de gestión de contenido en el Proyecto RECIF. Para el análisis de la información existen cuatro acciones a tomar: de descripción; de representación; preliminares y complementarias, de las cuales podemos iniciar desde alguna, de acuerdo al tema que queremos encontrar o catalogar. Veamos algunos ejemplos relacionados:

• Si no tenemos un vídeo para una clase específica, con base en la figura 7 identificaremos el área de acción, entonces identificamos que debemos iniciar en «acciones preliminares» y así comenzaremos a hacer una búsqueda de un vídeo adecuado para el tema seleccionado, pudiendo pasar de esta área de acción de análisis a las siguientes, según la figura 7 propuesta por los autores.

• Si contamos con un vídeo, pero no sabemos cómo catalogarlo: tomamos «acciones de creación», haciendo un análisis del vídeo, posteriormente pasamos al área de «acciones de representación» e indexamos el contenido encontrado.

En el campo de la tecnología fueron propuestas seis teorías (figura 3: doi.org/tnb) a lo largo de los últimos años. Y de las teorías tradicionales de aprendizaje presentadas en la figura 4 (doi.org/tnc), se puede decir que el proyecto RECIF se centra principalmente en las teorías de las corrientes humanistas de la educación, es decir, el aprendizaje significativo (misma línea del elearning). De la misma manera, el aprendizaje significativo da importancia a las variables internas del aprendizaje de cada individuo y considera la conducta humana como una totalidad. Esto es lo que puede reflejarse en el proyecto RECIF, ya que los recursos son puestos a disposición y son encontrados según las necesidades de los usuarios de la Plataforma.

Para Texeira y otros (2014), las principales teorías de aprendizaje se dividen de acuerdo a las necesidades principales del aprendizaje: Asociacionistas y mediacionales (figura 4).

La implementación del proyecto RECIF se centra en el tipo de teorías asociacionistas, ya que éstas buscan principalmente el raciocinio del individuo (objetivo del proyecto), sea una experiencia o un aprendizaje por medio de escenas fílmicas proporcionadas.

4.3. Dimensión estratégica del Proyecto RECIF

Los espacios del siglo XXI de intercambio de investigaciones y materiales aplicados a la educación fomentaron el desarrollo de repositorios de los más diferentes dominios para objetos de aprendizaje, muchos de los cuales están disponibles gratuitamente.

Sin embargo, la diversificación de las informaciones es pequeña, especialmente cuando son evaluados los contenidos y objetos destinados a la enseñanza superior. Dada la necesidad de ampliar las oportunidades entre los investigadores sobre el tema, cabe identificar los espacios virtuales (Hernández & al., 2014) de intercambios de experiencias y de innovación, aplicables a la enseñanza superior basada en tecnologías, para así obtener una herramienta de aprendizaje interactivo y colaborativo (Leinonen & Durall, 2014).

El análisis de la información con énfasis en la dimensión estratégica ha actuado en cuestiones de seguridad en los contenidos compartidos, con la facilidad y el acceso a las plataformas federadas con una única identidad y la ampliación del uso de objetos de aprendizaje desarrollados. La divulgación del contenido federado implica distintos cuestionamientos de seguridad, es por ello que se tiene que pertenecer a portales web de suministro de contenidos federados confiables.

La idea de la diseminación de los proyectos como RECIF, en el concepto como producto, es la mejoría e implantación de la plataforma con vistas a compartir las experiencias.

El concepto está basado en tres ideas fundamentales:

• Basado en redes federadas (interconectadas).

• La diseminación se realiza mediante la tecnología de Internet en un ordenador con el enfoque en el usuario.

• El enfoque es en el aprendizaje, en su sentido más extenso.

El uso de Internet permite la actualización de la información, la diseminación y su distribución virtualmente instantánea. Se observa que las personas cada vez tienen menos tiempo para aprender y por eso necesitan de un ritmo más veloz que le proporcione el aprendizaje. Y los repositorios digitales, como el proyecto RECIF, ofrecen al usuario final un medio para hacerlo rápidamente y al mismo tiempo compartirlo. Las perspectivas futuras conducen a que el espacio se torne colaborativo con posibilidad de conectarse a otras instituciones asociadas en cualquier parte del mundo, de esta manera se oferta una base fílmica para uso de prácticas en aulas para el estudio superior.

5. Consideraciones finales

Conforme se expuso al inicio de esta investigación, para llegar a los resultados esperados, que son que se comparta el conocimiento, la información y las experiencias entre los usuarios que hagan uso de la arquitectura planteada, se concluye que eso se logra haciendo identificación del material correcto (vídeo) en paralelo a su distribución online. De esta forma, en la aplicación del vídeo, los jóvenes reflexionan sobre la realidad experimentada y se expresan por vía del lenguaje, mediante la manipulación de los signos presentes en el vídeo seleccionado, procesando las informaciones. En el proceso semiótico, se hace uso de la información para hacer generalizaciones y previsiones. El profesor hace la relación de la teoría a ser transmitida como una analogía por medio del vídeo y los aspectos observados en cada alumno, en cuanto a las existencias (hechos, ideas y sensibilidades), que asimilados generan informaciones y conocimientos individuales.

Las tecnologías nuevas proveen de aplicaciones que crean, en su utilización del aprendizaje escolar, un modelo nuevo de materiales para el proceso de enseñanza–aprendizaje. Las funciones proporcionadas por las plataformas federadas pueden funcionar como «una clase después de una clase», en un espacio virtual donde los alumnos y el profesor tienen contacto. También les aportan un nuevo sentido a los recursos didácticos. Las plataformas federadas ofrecen un intercambio de opiniones donde también, los alumnos y profesores pueden crear su propio espacio vinculado con temáticas educativas. Sitios web como YouTube, pueden ayudar a que las informaciones vistas en clase puedan ser compartidas, así como también las opiniones de profesores o alumnos sobre algún tema.

Este trabajo consiste en presentar el proyecto RECIF para ser puesto a disposición de un sistema federado, el cual posee contenido informacional fílmico para objetivos pedagógicos. El proyecto exige un análisis de escenas fílmicas en conjunto con la semiótica para la extracción de la información y significados implícitos, y posteriormente la organización de ese conocimiento. Conforme a lo propuesto en el objetivo del presente trabajo, fue posible explorar las teorías involucradas en el Proyecto RECIF, y mostrar cómo se realiza el análisis de la información del mismo en una plataforma federada, con el enfoque en la recuperación de contenidos informacionales adecuados para el propósito del aprendizaje.

Se investigaron las técnicas utilizadas para la organización de la información y del conocimiento en el proyecto RECIF (escena fílmica como producto informacional), objeto de contenido y la utilización del vídeo en un repositorio digital. Fue descrito específicamente el funcionamiento del proyecto desde su alcance operacional hasta el conceptual y realizada una descripción de cómo se hace un análisis de información hasta su relación con las teorías de aprendizaje, que sustentan el proyecto como un método que bien gestionado se puede transformar en una herramienta eficaz de aprendizaje.

En el estudio se puede apreciar que la enseñanza–aprendizaje es efectiva si es bien gestionada por herramientas tecnológicas, en el caso especial de las plataformas federadas, que ofrecen recursos especiales en el campo didáctico para contribuir al crecimiento del conocimiento de quien lo consulta, sea alumno o profesor, pudiendo también de esta manera recrear el conocimiento al fortalecer el aprendizaje en clase.

Las tecnologías online al ser usadas como herramientas del conocimiento constructivista, crean una experiencia sobre el aprendizaje tradicional que resulta diferente en el proceso de enseñanza–aprendizaje, con mejores resultados entre los estudiantes. De esta manera incentivan su manera de aprender, por lo tanto aprenden mejor y construyen su propio conocimiento.

Por lo tanto, esta investigación viene a contribuir con la propuesta de una arquitectura, que incentiva a docentes, alumnos y/o investigadores, en la recuperación/colaboración de objetos de aprendizaje, además de poder ser implementado a bajo costo, por su aplicación de software libre.

Referencias

Aguaded, J.I., Vázquez-Cano, E. & Sevillano, M.L. (2013). MOOCs, ¿turbocapitalismo de redes o altruismo educativo? En Scopeo Informe, 2: MOOC: Estado de la situación actual, posibilidades, retos y futuro. (pp. 74-90). Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca Servicio de Innovación y Producción Digital. (goo.gl/slqguU) (22-06-2014).

Al-Atabi, M. & DeBoer, J. (2014). Teaching Entrepreneurship Using Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). Technovation, 34, 4, 261-264. (doi.org/tmk).

Alcides, R. (2009). Mídia digital: o papel do filme de animação como recurso de informação na geração da aprendizagem. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso, UFPR, Curitiba. (goo.gl/Qfqy8Y) (10-07-2014).

Almeida, M.G. & Freitas, M.C.D. (Org.). (2012). A Escola no Século XXI, 2: Docentes e Discentes na Sociedade da Informação. Rio de Janeiro: Brasport.

Badpa, A., Yavar, B., Shakiba, M. & Singh M.J. (2013). Effects of Knowledge Management System in Disaster Management through RFID Technology Realization. Procedia Technology, 11, 785-793. (doi.org/tmm).

Baptista, D.M., Araújo JR., R.H. & Carlan, E. (2010). O escopo da análise de informação. In: J. Robredo, M.J. Bräscher & M. Bräscher (Orgs.), Passeios no bosque da informação: estudos sobre representação e organização do informação e do conhecimento. Brasília DF: IBICIT. (goo.gl/kt4X56) (02-01-2014).

Barros, N.V. (2005). Curso: Capacitação para Conselhos Tutelares (Projeto SIPIA) ministrado na Faculdade de Administração-Niterói /UFF.

Belloni, M.L. (1998). Tecnologia e formação de professores: rumo a uma pedagogia pós-moderna? Educação e Sociedade, 19, 65, 143-162. (doi.org/d38f7q).

Bévort, E. & Belloni, M. (2009). Mídia-educação: conceitos, história e perspectivas. Educación Social, 30, 109, 1081-1102. (doi.org/fw7jm7).

Bouchard, P. (2011). Network Promises and their Implications. In The Impact of Social Networks on Teaching and Learning. RUSC, 8,1, 288-302. (goo.gl/Y7TSZK) (23-06-2014).

Bueno, N.L. (1999). O desafio da formação do educador para o ensino fundamental no contexto da educação tecnológica. Curitiba: Dissertação de Mestrado, PPGTE-CEFET/PR.

Cabero, J. & Marín, V. (2014). Posibilidades educativas de las redes sociales y el trabajo en grupo. Percepciones de los alumnos universitarios. Comunicar, 42, 165-172. (doi.org/tmt).

Chella, M.T. (2004). Sistema para Classificação e Recuperação de Conteúdo Multimídia Baseado no Padrão MPEG, 7. São Paulo: UNICAMP.

Cormier, D. (2008). The CCK08 MOOC - Connectivism course, 1/4 way. Dave’s Educational Blog. (goo.gl/tskvev) (22-06-2014).

Davies, D., Jindal-Snape, D., Collier, C., Digby, R., Hay, P. & Howe, A. (2013). Creative Learning Environments in Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8, 80-91 (doi.org/tmn).

Dillenbourg, P., Järvelä, S.Y. & Fischer, F. (2009). The Evolution of Research on Computer-supported Collaborative Learning. In Technology-enhanced Learning, Springer Netherlands, 3-19.

Duarte, J. & Barros, A. (Eds.) (2005). Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa em comunicação. IASBECK, Luiz Carlos Assis. São Paulo: Atlas. Eishani, K.A., Saa’d, E.A. & Nami, Y. (2014). The Relationship between Learning Styles and Creativity. Procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 52-55 (doi.org/tms).

Feria, L.B. & Machuca, P. (2014). The Digital Library of Iberoamerica and the Caribbean: Humanizing Technological Resources. The International Information & Library Review, 36, 3, 177-183 (doi.org/cc4p57).

Galagan, P. (2003). The Future of the Profession Formerly known as Training. T&D Magazine, 57, 12, 26-38.

Hernández, N., González, M. & Muñoz, P.C. (2014). La planificación del aprendizaje colaborativo en entornos virtuales. Comunicar, 42, 25-33. (doi.org/tmp).

Kassim, H., Nicholas, H. & Ng, W. (2014). Using a Multimedia Learning Tool to Improve Creative Performance. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 13, 9-19 (doi.org/tmr).

Le-Coadic, Y.F. (1996). A ciência da informação. Brasília, DF: Briquet de Lemos.

Leinonen, T. & Durall, E. (2014). Pensamiento de diseño y aprendizaje colaborativo. Comunicar, 42, 107-116. (doi.org/tmq).

Little, G. (2013). Massively Open? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39, 3, 308-309. (doi.org/tmv).

Liyanagunawardena, T., Adams, A. & Williams, S. (2013). MOOCs: A Systematic Study of the Published Literature 2008-12. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14, 3, 202-227. (doi.org/tmw).

MacPhail, A., Tannehill, D. & Karp, G.G. (2013). Preparing Physical Education Preservice Teachers to Design Instructionally Aligned Lessons through Constructivist Pedagogical Practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 33, 100-112. (doi.org/tmx).

Mavers, D. (2009). Student Text-making as Semiotic Work. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 9, 2, 141-155. (doi.org/bwbn34).

McAuley, A., Stewart, B., Siemens, G. & Cormier, D. (2010). The MOOC Model for Digital Practice. (goo.gl/ljmvEl) (23-06-2014).

Means, B. (1993). Using Technology to Support Education Reform. Education Development Corporation. U.S. Department of Education. September. (goo.gl/SQ9uaa) (30-04-2014).

Méndez García, C. (2013). Diseño e implementación de cursos abiertos masivos en línea (MOOC): expectativas y consideraciones prácticas. RED, 39, 1-19. (goo.gl/pHHweM) (11-07-2014).

Napolitano, M. (2006). Como usar o cinema na sala de aula. 4. Ed. São Paulo: Contexto.

Nikou, S. & Bouwman, H. (2014). Ubiquitous Use of Mobile Social Network Services. Telematics and Informatics, 31, 3, 422-433 (doi.org/tmz).

Ooi, Keng-Boon. (2014). TQM: A Facilitator to Enhance Knowledge Management? A Structural Analysis. Expert Systems with Applications, 41, 11, 5167-5179. (doi.org/tm2).

Pappano, L. (2012). The year of the MOOC.The New York Times. (goo.gl/3P2yPG) (22-06-2014).

Ranker, J. (2014). The Emergence of Semiotic Resource Complexes in the Composing Processes of Young Students in a Literacy Classroom Context. Linguistics and Education, 25, 129-144. (doi.org/tm3).

Rezende, D.A. & Abreu, A.F. (2006). Tecnologia da informação aplicada a sistemas de informação empresarial: o papel estratégico da informação e dos sistemas de informação nas empresas. São Paulo: Atlas.

Rosenberg, M.J. (2005). Beyond e-Learning: Approaches and Technologies to Enhance Organizational Knowledge, Learning and Performance. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Santos L.R.N. (2009). Proposta de modelagem para recuperação de conteúdo informacional em filmes. Monografia de conclusão de curso em Gestão da Informação. Curitiba: UFPR. (goo.gl/Pa4PZk)(10-07-2014).

Sitti, S., Sopeerak, S. & Sompong, N. (2013). Development of Instructional Model Based on Connectivism Learning Theory to Enhance Problem-solving Skill in ICT for Daily Life of Higher Education Students. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103, 315-322. (doi.org/tm5).

Teixeira, C.E.J. (1995). A Ludicidade na Escola. São Paulo: Loyola.

Texeira, A., Ferreira, E. & Sousa, E. (2014). Preparatório para o concurso da SEMED. Secretaria Municipal de Educação. , Brasil: Governo do Manaus.

Vázquez-Cano, E. & López, M.E. (2014). Los MOOC y la educación superior: la expansión del conocimiento. Profesorado, 18, 1, 1-10.

Vázquez-Cano, E., Sirignano, F., López M.E. & Román, P. (2014). La globalización del conocimiento: Los Moocs y sus recursos. II Congreso Virtual Internacional sobre Innovación Pedagógica y Praxis Educativa. Sevilla, 26-28 de marzo.

Vizoso, C.M (2013). ¿Serán los COMA (MOOC), el futuro del e-learning y el punto de inflexión del sistema educativo actual? Boletín SCOPEO, 79. (goo.gl/NjoLRA) (22-06-2014).

Young, J. (2012). Inside the Coursera Contract: How an Upstart Company Might Profit from Free Courses. The Chronicle of Higher Education. (goo.gl/xxkd5S) (22-06-2014).

Document information

Published on 31/12/14

Accepted on 31/12/14

Submitted on 31/12/14

Volume 23, Issue 1, 2015

DOI: 10.3916/C44-2015-07

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?