(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== This...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 161060573 to Kruger et al 2017a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 09:07, 28 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This study investigates the impact of same-language subtitles on the immersion into audiovisual narratives as a function of the viewer’s language (native or foreigner). Students from two universities in Australia and one in Spain were assigned randomly to one of two experimental groups, in which they saw a drama with the original English soundtrack either with same-language English subtitles (n=81) or without subtitles (n=92). The sample included an English native control group, and Mandarin Chinese, Korean, and Spanish groups with English as a foreign language. Participants used post-hoc Likert scales to self-report their presence, transportation to the narrative world, perceived realism, identification with the characters, and enjoyment. The main results showed that subtitles did not significantly reduce these measures of immersion. However, subtitles produced higher transportation, identification with the characters, and perceived realism scores, where the first language of viewers and their viewing habits accounted for most of this variance. Moreover, presence and enjoyment were unaffected by either condition or language. Finally, the main results also revealed that transportation to the narrative world appears to be the most revealing measure of immersion in that it shows the strongest and most consistent correlations, and is a significant predictor of enjoyment.

1. Introduction and state of the art

When we watch a film or television (particularly, but not exclusively, fiction) our attention is captured to such an extent that our awareness of our immediate surroundings sometimes becomes diminished or suppressed. We watch television or film because we want to be, or cannot help becoming, immersed in the world portrayed to us on the screen before us. This process of immersion is of course not limited to audiovisual text like film, but also occurs in the context of written narrative fiction. Audiences could therefore be said to select media to satisfy certain needs, such as the desire to escape from reality, to be transported into another reality, and the need to be entertained or to relax (McQuail, Blumler, & Brown, 1972). Similarly, for an audience to enjoy television and film, they need to be immersed into or engaged with the fictional reality created by the film (Bilandzic & Busselle, 2011; Vorderer, Klimmt, & Ritterfeld, 2014; Sasamoto & Doherty, 2015).

When we add subtitles as an additional textual element at the bottom of the screen, audiences often feel that the aesthetics of the film are marred by the subtitles, that the image is smudged. In addition to providing access to audiovisual texts to audiences excluded either from the language of the dialogue or from the soundtrack, subtitling has long been hailed as an important tool in language learning, language proficiency, and comprehension. Many studies have already confirmed the benefits of subtitles, particularly in language learning (Danan, 2004; Diao & al., 2007; Garza, 1991; Vanderplank, 1988, 1990; Winke & al., 2013). In the context of fiction film, it has likewise been established that, in spite of anecdotal complaints about the fact that subtitles somehow smudge the image, audiences process subtitles very effectively (d’Ydewalle, Praet, Verfaille, & Van Rensbergen, 1991; Perego, Del-Missier, Porta, & Mosconi, 2010; Perego, Del-Missier, & Bottiroli, 2014).

At a general level, immersion relates to the degree to which a viewer becomes absorbed in a fictional reality. In Media Psychology, the term is used in the same context as transportation and character identification (Green & al., 2004; Tal-Or & Cohen, 2010) but also with concepts such as presence, flow and enjoyment (Wissmath, Weibel, & Groner, 2009), or perceived realism (Cho & al., 2014). Immersion, as well as the related term of engagement, is also viewed as a product of transportation into fictional worlds, character identification, presence, and perceived realism (Bilandzic & Busselle, 2011; Soto-Sanfiel, 2015).

This immersion in film is a relatively sensitive cognitive state. It could, for example, be influenced by factors external to the film, like the physical context of viewing (at home or in a cinema or while traveling) or the social context (alone, with family, with friends or with strangers). What we are interested in here in the first instance, is whether the textual element of subtitles (which is technically external to the film, yet represents the dialogue), will have an impact on immersion. In the second instance, we are interested in the impact of language (that of the viewer, that of the film and that of the subtitles) on immersion.

At an intuitive level it is reasonable to expect that the audience’s immersion in film will not be unaffected by the addition of subtitles for the simple reason that visual attention is divided. In other words, unlike the viewer who watches the unsubtitled film, the viewer who watches the subtitled film has to divide visual attention between the image and the words at the bottom of the screen. When viewers do not have access to the audio, or do not understand the language of the dialogue, they are dependent on the subtitles to understand the film, so there is an obvious trade-off. However, when viewers do have access to the audio and understand the language of the dialogue, the subtitles become a redundant source of information. In this case, the viewers may still use the (same language) subtitles to read along with the spoken words, particularly if the latter are not in their first language. The viewer may of course ignore the subtitles, but this is not likely as it has been established empirically that viewers read subtitles automatically regardless of whether they understand the language of the audio (d’Ydewalle & al., 1991). The notion that viewers attend to subtitles automatically is also supported by research on the effect of abrupt onset on the capturing of attention (Remington, Johnston, & Yantis, 1992).

When reading subtitles, viewers therefore have to process an additional visual and verbal source of information that should theoretically impose an additional cognitive load. In the words of Lee & al. (2013: 414), “subtitled films likely tax the attention and memory systems because there is visual information (the scene), as well as verbal information in the form of written, rather than audio, dialog”. In this article, we are interested in determining whether this additional processing results in a decrease in immersion in the story world of the film. In a previous study (Kruger et al., forthcoming), we reported on the first stage of an experiment designed to determine the impact of subtitles on immersion. The material was one episode of an American medical drama (House MD) with English dialogue and same-language English subtitles. English, Korean and Chinese participants saw the drama either with or without subtitles. This stage was conducted as a pilot to test the validity and reliability of different scales (presence, transportation, character identification, and perceived realism) to determine the impact of the two conditions (subtitled and unsubtitled). Findings from this pilot show no negative impact on immersion caused by same-language subtitles in the above groups.

In this article, we report on a second stage of the experiment in which we expand the sample size, but in which we also investigate the impact of language on immersion. Using an English control group, we aim to determine whether the first language of the audience has an impact on immersion, or whether there is an interaction between language and condition on the different immersion scales. We are also interested in determining whether the dimensions of presence, transportation, character identification and perceived realism are related and similar to Wissmath & al. (2009) and Soto-Sanfiel (2015), and how these dimensions are related to enjoyment.

1.1. Subtitling and immersion

Subtitles compete for visual attention, and therefore draw upon finite cognitive attentional resources to process their visual information. Nevertheless, viewers seem to be able to process subtitles efficiently (d’Ydewalle & al., 1991; Perego & al., 2010; Perego & al., 2014). In their study, Lee & al. (2013) investigate the impact of subtitles on local and global coherence, finding lower global coherence, but higher local coherence in the presence of subtitles. Essentially this means that participants who watched a film in their first language could make more inferences to assist in global coherence which made it possible to comprehend the narrative as a whole and keep track of events and characters. However, participants who watched the same film in a foreign language with standard subtitles in their first language, could make fewer such inferences, but could make more inferences at the local level allowing them to have a better sense of the local coherence of scenes, but at the expense of global coherence. They conclude that viewers who have to switch between reading the written dialogue in the subtitles and the scene have a decreased ability to make global inferences due to the fact that their cognitive resources (including attention, working, long-term, and long-term working memories) are taxed more than in the unsubtitled condition. However this may suggest that there would be a knock-on effect on immersion, with immersion also being affected negatively by the subtitled condition. Building upon this, the context of our study is same language subtitling, where the audience is not reliant on the subtitles for access to the dialogue, but the subtitles merely confirm the dialogue in written form.

In this regard, Lavaur and Bairstow’s (2011) investigation of the impact of subtitles on film comprehension in relation to the viewers fluency level is particularly interesting to our study. In their study, they compared the visual processing and dialogue comprehension of French viewers with beginner, intermediate and advanced English proficiency levels when watching a film clip in original English without subtitles, and with English or French subtitles. They found that for beginners, the visual processing decreased from unsubtitled to English subtitles, to French subtitles (i.e. becoming worse the higher their reliance was on the subtitles), whereas the dialogue comprehension had the opposite trend. In other words, for this group, visual data were extremely important for their comprehension. The advanced group had higher visual processing and dialogue comprehension in the unsubtitled version where there was no distraction by subtitles, indicating that subtitles were unnecessary for their comprehension. The advanced group’s visual processing and dialogue comprehension were hampered. In the intermediate group, subtitles did not have any impact on either source. Their study did not, however, investigate either immersion or enjoyment, although the interaction between comprehension and immersion and enjoyment is an interesting theoretical question that we will later revisit. Further to this, Wissmath & al. (2009) established that a subtitled version of a film does not result in less immersion than a dubbed version of the same film when measured by means of self-reported spatial presence, transportation, flow and enjoyment. In that study, it was found that foreign language subtitles (i.e. audio dubbed into the language of the audience with subtitles in a foreign language) did reduce the immersion, presumably as a result of the distraction the incomprehensible subtitles cause. Perego & al. (2014) similarly established that a dubbed version of a film does not hold any cognitive or evaluative advantages over a subtitled version of the film in either young or older adult viewers.

These findings by Wissmath & al. (2009) and Perego & al. (2014) only focus on the difference between subtitled and dubbed versions of a film. In this study, we investigate the impact of the presence or absence of same-language subtitles (original English soundtrack and English subtitles) on psychological immersion and enjoyment. Furthermore, in addition to the two conditions of subtitled and unsubtitled film, we investigate the influence of language on immersion by testing groups of English native speakers and Chinese, Korean and Spanish-Catalan speakers who have English as a foreign language. Unlike the previous studies, in which the audience did not understand the language of either the subtitles or the audio, this study focuses on the impact of the visual interference of subtitles on psychological immersion and enjoyment, rather than the impact of translation-related variables such as equivalence at some level or translation shifts.

1.2. Measuring immersion

Media immersion, or immersion in mediated environments like film, television, fiction, and virtual reality is typically measured through subjective self-report scales on dimensions including presence, transportation, identification and perceived realism. In this study we used the dimensions of presence, transportation, character identification, and perceived realism thus removing the confound of interlingual translation, which is a rich and complex psycholinguistic and sociocultural process.

Originally termed “telepresence” in reference to the feeling that users of technical devices have of being located in physically remote places, presence is used to describe the feeling experienced by media users that that they are spatially located in a mediated environment (Wissmath & al., 2009). As such, it involves the sense of “being there”, having departed or faded from the proximal environment and having arrived or self-located in the mediated environment. The perception of presence in a mediated environment can refer to a spatial sense of being located in a fictional reality, or to a social sense of being located in the presence of fictional characters.

According to Wissmath & al. (2009), technological aspects have been overemphasized in presence research, resulting in a shift of emphasis to the inclusion of user characteristics in transportation theory. Transportation denotes that the reader is plunged into the fictional world by suspending real-world facts (Green & Brock, 2000). It can also be defined as “the experience of cognitive, affective and imagery involvement in a narrative” (Green & al., 2004: 11), with the viewer forgetting about their immediate surroundings. Green and Brock’s (2000) focus was mainly on testing transportation in the reading of fiction, although they also extend this to film viewing. In the opinion of Wissmath & al., (2009), transportation overlaps conceptually with the willing suspension of disbelief (i.e. the viewer or reader allowing themselves to suppress the awareness that what they are reading or watching is not real).

Tal-Or and Cohen (2010) adapted the items used by Green and Brock to measure the self-reported transportation of film viewers in particular. They also added items to measure character identification. We use these scales in the current study as measures of transportation and character identification. Character identification is important in that it makes it possible for viewers to experience the fictional reality from the perspective of a character in that reality. According to Cohen (2001), character identification is a key aspect in the understanding of media entertainment and its effects, particularly due to its influence on narrative enjoyment (Igartua, 2010; Soto-Sanfiel & al., 2010).

The phenomenon of identification relates to the affinity with characters experienced by viewers (Cohen, 2001), making it possible for viewers to put themselves in the shoes of a character. Character identification is measured by means of a number of scales such as that developed by Igartua & Páez (1998) and refined by subsequent works (Igartua, 2010; Soto-Sanfiel & al., 2010). The other scale was proposed by Cohen (2001). All of these works characterize identification as a multidimensional concept formed by a cognitive empathy, an emotional empathy, and the ability to fantasize, imagine or merge. Both presence and transportation concern the degree to which an audience becomes less aware of its immediate surroundings. Another dimension that is relevant to media immersion is the extent to which the audience believes the mediated environment or film is realistic. This has been termed “perceived realism” (Cho & al., 2014) and establishes the impact of a narrative in relation to persuasion, looking at dimensions of audience involvement. Cho & al. (2014) identify five sub-dimensions of perceived realism, namely:

1) Plausibility (could the presented behavior and events occur in the real world?).

2) Typicality (are narrative portrayals within the parameters of the audience’s past and present experiences?).

3) Factuality (does the narrative seem to portray a specific individual or event in the real world?).

4) Narrative consistency (are the story and its elements congruent and coherent, without contradictions?).

5) Perceptual quality (do audio, visual and other manufactured elements comprise a convincing and compelling portrayal of reality?).

In using the dimensions of presence, transportation, character identification and the subsets of perceived realism as different but related dimensions of psychological immersion, we believe that we can achieve a nuanced description of the impact of subtitles on the audience’s immersion in the fictional world.

1.3. Hypothesis

Based on the review of literature and the study’s overarching research questions, we propose the following hypotheses:

• H1. There are significant positive correlations between all of the immersion scales: transportation; character identification; presence; and perceived realism.

• H2. The Subtitled condition does not result in significantly lower scores on any of the immersion scales than the Unsubtitled.

• H3. The English group does not result in significantly higher scores on any of the immersion scales than do the other language groups: Chinese; Korean; and Spanish.

• H4. There are no significant interactions between condition and language on any of the immersion scales.

• H5. A significant predictor of enjoyment can be identified from the immersion scales.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A convenience, self-selecting sampling method was chosen to gather data for English native speakers and those with English as a foreign language all of whom were university students at the institutions mentioned below. This method was mirrored at each institution to include a variety of languages: two universities in Sydney, Australia (Macquarie University and The University of New South Wales), and one in Barcelona, Spain (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona). We did not put an initial restriction on language and obtained sufficient numbers to include them all. The total sample contained 173 valid responses, aged between 18 and 49 (M=25.79, SD=5.84) and distributed across 101 females and 74 males. Participants were assigned randomly to the Subtitled or Unsubtitled condition. The Subtitled (n=81) contained: 23 English; 19 Chinese; 13 Korean; and 26 Spanish, and the Unsubtitled (n=92) contained 24 English; 22 Chinese; 13 Korean: and 33 Spanish. Subjects in the Subtitled condition saw the episode in English with English same-language subtitles, and participants in the Unsubtitled saw the episode without any subtitles. Ethics clearance for research involving human participants was approved at each of the author’s institutions. All of them were recruited via anonymous course e-mail lists and printed posters at the author’s home institutions. Participation was voluntary and not remunerated in any way. The data collection was performed between January and March of 2015.

2.2. Materials

As stimulus, we used a video from the eighth season of the American investigative medical drama series, House, MD (2011). In order to preserve cohesion and authenticity, we used the full-length fourth episode (Risky Business, 44 minutes). It has fast-paced editing, a high volume of dialogue that contains some specialized terminology, and a strong narrative structure, thus making it an ideal test-bed for subtitles and immersion. Participants watched the episode in groups in a small lecture theatre on a large screen with excellent sound quality and high-definition video quality. The lights were dimmed and participants were asked to refrain from using mobile devices and from interacting with other participants. The experiment took approximately 90 minutes.

After watching the film, participants completed three sets of questionnaires: biographical, language, and immersion. Biographical data were obtained through a biographical questionnaire. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q) proposed by Marian, Blumenfeld, & Kaushanskaya (2007) captured language data. A 44-item immersion questionnaire measured immersion using 7-point Likert scales (see Appendix for questionnaires). For transportation, 10 items were used scaled from “not at all” to “very much” and for character identification 4 items were scaled similarly, both adapted from Tal-Or & Cohen (2010), who, in turn, adapted the transportation scales from Green & Brock (2000). Presence was measured by means of 8 items (adapted from Kim & Biocca, 1997), scaled from “never” to “always”. Perceived realism (adapted from Cho & al., 2014) was measured with 21 items scaled from “not at all” to “very much”, including subscales: plausibility (5), typicality (3), factuality (3), narrative consistency (5), and perceptual quality (5). A number of items were reverse-scored. Finally, enjoyment was measured with a single item following studies relating presence and transportation with enjoyment (Green & Brock, 2000; Tal-Or & Cohen, 2010; Wissmath & al., 2009).

2.3. Procedure

A 2x4 factorial design was used wherein condition (Subtitled, Unsubtitled) and language (English, Chinese, Korean, Spanish) were tested against each of the individual immersion scales (Transportation, Character identification, Presence, Perceived realism, Enjoyment) using ANCOVAs. In all cases, included covariates were: months spent in an English-speaking country in the last ten years, average TV viewing per day, and subtitle usage in English and other languages.

All continuous variables were tested using Shapiro-Wilk’s test and visual inspection to verify normal distribution. Months in an English speaking-country, average TV viewing per day, and both subtitle usage variables were not normally distributed (p>.05) and were logarithmically transformed to meet this criterion. Reliability of all scales ranged from acceptable to good: transportation (a=.69), character identification (a=.77), presence (a=.71), and perceived realism (a=.89).

3. Results

3.1. Correlational Analysis

Significant positive correlations were found between all scales with insufficient evidence to assume multicollinearity. As each of the immersion scales shows a significant positive correlation with all of the others, H1 is supported. However, some of these correlations are weak, especially between presence and the other scales (table 1).

3.2. Transportation

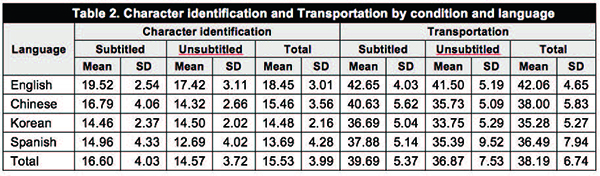

The scale has a possible range of 10-70 in total. A two-way ANCOVA found no significant interaction between condition and language on transportation [F(3, 160)=.654, p=.582, ?p2=.012]. A significant main effect was found for condition [F(1, 160)=8.550, p=.004, ?p2=.051], where the Subtitled condition was higher, but not for language [F(3, 160)=2.431, p=.065, ?p2=.044] as shown in table 2.

3.3. Character identification

The scale has a possible range of 4-28 in total. A two-way ANCOVA found no significant interaction between condition and language on character identification [F(3, 160)=.299, p=.826, ?p2=.006]. However, main effects for condition [F (1, 160)=11.896, p=.001, ?p2= .069] and language [F(3, 160)= 4.065, p=.008, ?p2=.071] were both found to be significant, where the Subtitled condition was higher (table 2). For language, a post-hoc Tukey test with Bonferroni adjustments for multiple comparisons shows the English group’s character identification was significantly higher than the Korean (p=.008), and Spanish (p=.013).

3.4. Presence

The scale has a possible range of 8-56 in total. A two-way ANCOVA found no significant interaction between condition and language on presence [F(3, 160)=1.532, p=.208, ?p2=.028 ] (table 3). This was also the case for main effects of condition [F(1, 160)=1.330, p=250, ?p2=.008] and language [F(3, 160)=2.699, p=.051, ?p2=.048].

3.5. Perceived realism

The scale has a possible range of 21-147 in total. A two-way ANCOVA found a significant interaction between condition and language on perceived realism [F(3, 160)=3.782, p=.012, ?p2=.066], where the Subtitled condition scored higher (table 3). Significant main effects were also found for average TV viewing per day [F(1,160)=4.003, p=.047, ?p2=.024] and subtitle usage in other languages [F(1, 160)=6.361, p=.013, ?p2=.038]. For language, a post-hoc Tukey test with Bonferroni adjustments for multiple comparisons shows significance with: English greater than Chinese (p=.009), Korean (p<.001), and Spanish (p<.001), as well as Chinese greater than Korean (p=.007), and Spanish (p=.02).

3.6. Enjoyment

The scale ranges from 1-7 in total as it is just one item. A two-way ANCOVA found no significant interaction between condition and language on perceived realism [F(3, 160)=.654, p=.582, ?p2=.012 (table 3]. Main effects for condition [F(1, 160)=2.086, p=.151, ?p2 =.013] and language were also not significant [F(3, 160)=2.214, p=.458, ?p2=.016].

In conclusion, we find sufficient evidence to show that the Subtitled condition does not result in lower levels of immersion, thus supporting Hypothesis II. Contrary to expectation, the Subtitled condition results in higher levels of transportation and character identification. We also find differences in immersion between language groups which reject Hypothesis III in that the English group reported significantly higher levels of character identification and perceived realism than the other languages. We note however that transportation, presence, and enjoyment were similar for all language groups. Lastly, we also reject Hypothesis IV given that that the English and Chinese groups reported significantly higher levels of perceived realism while all other immersion scales were similar.

3.7. Predicting enjoyment

Finally, a multiple regression analysis using the Enter method was run in order to identify significant predictors of enjoyment taking into account the previously identified covariates of: months in an English-speaking country, average TV viewing per day, and subtitle usage in English and other languages. There was independence of residuals, as assessed by a Durbin-Watson value of 1.623. Assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality were met, and no evidence of multicollinearity, high leverage or influence points was identified.

The model [F(8, 163)=4.772, p<.000, adj. R2=.15] found transportation to be the only significant predictor of enjoyment (table 4), accounting for a greater amount of the variance in enjoyment than any of the other scales of immersion. As the multiple regression analysis identified only transportation as being a significant predictor of enjoyment, this provides sufficient evidence to support Hypothesis V, but raises questions about the relationship between enjoyment and the other measures of immersion.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study contributes to the understanding of the role that subtitles play in the processes related to psychological immersion in film narratives. In particular, this study adds information about the relationship between the language of the subtitles and the receiver in predicting immersion and enjoyment, which had not been observed before.

Our results show that the subtitled condition did not result in significantly lower immersion on any of the scales either for the group as a whole or for any of the languages. This provides evidence for the argument that subtitles do not act as a distraction to viewers, even when in the same language. Adding subtitles therefore does not make it more difficult for the audience to become immersed in fictional reality. Viewers could be said to process subtitles as part of the story world as dialogue in a way similar to the processing of the auditory dialogue rather than as an extradiegetic element.

On examination of the immersion scales, it is interesting to note that subtitles resulted in significantly higher transportation, character identification and perceived realism. This provides evidence that subtitles facilitate the audience’s ability to feel involved in the story world and to put themselves in the position of characters.

We were also interested in the role of the language of the audience in the impact of subtitles on immersion. We found no interaction between condition and language on the scales of transportation, character identification or presence, although in the case of character identification, the English group did perceive a significantly higher degree of identification than the Korean and Spanish groups. This difference will have to be investigated further with the aid of language history data. There was, however, a significant interaction between language and condition in the perceived realism scale.

We were further interested in the relation between the different scales in the measurement of immersion. Transportation had the highest correlation with all the other scales, which seems to suggest that this set could be of particular value in the measurement of immersion in the context of audiovisual translation. The strongest correlation was found between transportation and character identification.

Although there was no interaction between language and condition in terms of enjoyment, transportation was found to be the only predictor of enjoyment. All of these findings would seem to suggest that the combination of transportation and character identification provides the most insightful post-hoc measurement of immersion in the context of AVT. Tal-Or & Cohen (2010) defined identification and transportation as two of the major concepts used to describe viewer involvement in entertainment, and establish that they are distinct processes. As such, the fact that subtitles resulted in increased identification with characters as well as transportation indicates that subtitles fulfil a focusing effect that, rather than distancing the audience from the fictional reality and the characters, allows them to gain a stronger connection with the story.

Additionally, we expected the identified covariates to play a more marked role in the process of immersion. Only in perceived realism did average TV viewing and usage of subtitles have a significant impact, although the presence of covariates, especially the number of months in English speaking countries, was necessary in order to avoid confounds in the above analyses.

To conclude, in the context of this particular dialogue-driven medical drama characterized by fast speech, medical terminology and a strong, contained narrative, same-language English subtitles resulted in increased immersion. This was the case particularly in the key dimensions of identification and transportation, which dispels concerns about subtitles distracting the audience. In this context, subtitles seem to focus attention, making it possible for the audience to confirm complicated auditory dialogue visually.

4.1. Limitations

The study is limited by the number of languages covered and by the rather superficial measurements of language proficiency available. Testing on additional language groups and using more in-depth linguistic information on competency and the nature of language and cultural distance could provide further insight. Additionally, testing across genres is also required to make our findings more generalizable. It might very well be that the strong effects found in the case of transportation and character identification will be less marked in genres that rely more on visual effects and action and where the division of attention between the dialogue and fast-moving visuals may come with some costs in terms of immersion.

Finally, it is necessary to take into account participants’ own individual interaction with immersion. The use of the Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire would effectively account for this. In the current study, however, it would have added a further 13 items and as the focus was on the various scales of immersion, these were prioritized. Future studies could make use of the Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire in tandem with scales of, based on our findings, transportation and enjoyment depending of course on the research questions and context.

References

Bilandzic, H., & Busselle, R.W. (2011). Disfrute of Films as a Function of Narrative Experience, Perceived Realism and Transportability. Communications, 36(1), 29-50. (http://goo.gl/zSFKs7) (2016-05-31).

Cho, H., Shen, L., & Wilson, K. (2014). Perceived Realism: Dimensions and Roles in Narrative Persuasion. Communication Research, 41(6), 828-851. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212450585

Cohen, J. (2001). Defining Identification: A Theoretical Look at the Identification of Audiences with Media Characters. Mass Communication Society, 4(3), 245-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01

Danan, M. (2004). Captioning and Subtitling: Undervalued Idioma Learning Strategies. Meta, 49, 67-77. https://doi.org/10.7202/009021ar

Diao, Y., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2007). The Effect of Written Text on Comprehension of Spoken Inglés as a Foreign Idioma. The American Journal of Psychology, 120(2), 237-261. (http://goo.gl/v3QhbZ) (2016-05-31).

D’Ydewalle, G., Praet, C., Verfaillie, K., & Van Rensbergen, J. (1991). Watching Subtitled Television: Automatic Reading Behavior. Communication Research, 18, 650-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323102017003694

Garza, T.J. (1991). Evaluating the Use of Captioned Video Materials in Advanced Foreign Idioma Learning. Foreign Idioma Annuals, 24(3), 239-258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1991.tb00469.x

Green, M. C., & Brock, T.C. (2013). Transport Narrative Questionnaire. Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Science. (http://goo.gl/2REoeG) (2016-05-31).

Green, M.C., Brock, T.C., & Kaufman, G.F. (2004). Understanding Media Disfrute: the Role of Transportation into Narrative Worlds. Communication Theory, 14(4), 311-327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00317.x

Igartua, J.J. (2010). Identification with Characters and Narrative Persuasion through Fictional Feature Films. Communications. The European Journal of Communication Research, 35(4), 347-373. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2010.019

Igartua, J.J., & Páez, D. (1998). Validez y fiabilidad de una escala de empatía e identificación con los personajes. Psicothema, 10(2), 423-436. (http://goo.gl/W3vssl) (2016-05-31).

Kim, T., & Biocca, F. (1997). Telepresence via Television: Two Dimensions of Telepresence may have different Connections to Memory and Persuasion. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00073.x

Kruger, J-L., Soto-Sanfiel, M.T., Doherty, S., & Ibrahim, R. (forthcoming). Towards a Cognitive Audiovisual Translatology: Subtitles and Embodied Cognition. In R. Muñoz-Martìn (Ed.), Reembedding Translation Process Research (pp. 171-194). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lavaur, J.M., & Bairstow, D. (2011). Idiomas on the Screen: Is Film Comprehension related to Viewers’ Fluency Level and to the Idioma in the Subtitles? International Journal of Psychology, 46(6), 455-462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.565343

Lee, M., Roskos, B., & Ewoldsen, D.R. (2013). The Impact of Subtitles on Comprehension of Narrative Film. Media Psychology, 16(4), 412-440. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.826119

McQuail, D., Blumler, J.G., & Brown, J.R. (1972). The Television Audience: A Revised Perspective. In D. McQuail (Ed.), Sociology of Mass Communication (pp. 135-165). Middlesex, UK: Penguin.

Perego, E., Del-Missier, F., & Bottiroli, S. (2014). Dubbing versus Subtitling in Young and Older adults: Cognitive and Evaluative Aspects. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 23(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2014.912343

Perego, E., Del-Missier, F., Porta, M., & Mosconi, M. (2010). The Cognitive Effectiveness of Subtitle Processing. Media Psychology, 13(3), 243-272. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2010.502873

Remington, R.W., Johnston, J.C., & Yantis, S. (1992). Involuntary Attentional Capture by Abrupt Onsets. Perception and Psychophysics, 51(3), 279-290. (http://goo.gl/5KRgy0) (2016-05-31).

Sasamoto, R., & Doherty, S. (2015). Towards the Optimal Use of Impact Captions on TV Programmes. In M. O’Hagan, & Q. Zhang (Eds.), Conflict and Communication: A Changing Asia in a Globalising World (pp. 210-247) Bremen, Germany: EHV Academic Press.

Soto-Sanfiel, M.T. (2015). Engagement and Mobile Listening. International Journal of Mobile Communication, 13(1), 29-50. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijmc.2015.065889.

Soto-Sanfiel, M.T., Aymerich-Franch, L., & Ribes, F.X. (2010). Impacto de la interactividad en la identificación con los personajes. Psicothema, 22(4), 822-827. (http://goo.gl/kvrJzc) (2016-08-11).

Tal-Or, N., & Cohen, J. (2010). Understanding Audience Involvement: Conceptualizing and Manipulating Identification and Transportation. Poetics, 38: 402-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2010.05.004

Vanderplank, R. (1988). The Value of Teletext Sub-titles in Idioma Learning. ELT Journal, 42(4), 272-281. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/42.4.272

Vanderplank, R. (1990). Paying Attention to the Words: Practical and Theoretical Problems in Watching Television Programmes with Uni-lingual (CEEFAX) Sub-titles. System, 18(2), 221-234.

Vorderer, P., Klimmt, C., & Ritterfeld, U. (2004). Disfrute: At the Heart of Media Entertainment. Communication Theory, 14(2), 388-408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00321.x

Winke, P., Gass, S., & Syderenko, T. (2013). Factors Influencing the Use of Captions by Foreign Idioma Learners: An Eye Tracking Study. The Modern Idioma Journal, 97(1), 254-275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.01432.x

Wissmath, B., Weibel, D., & Groner, R. (2009). Dubbing or Subtitling? Effects on Presence, Transportation, Flow, and Disfrute. Journal of Media Psychology, 21(3), 114-125. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105.21.3.114

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Se estudia el impacto de los subtítulos en el mismo idioma de la narrativa audiovisual según el idioma del receptor (nativo o extranjero). Estudiantes de dos universidades australianas y una española fueron asignados al azar a uno de dos grupos experimentales en los que se veía un drama con la banda sonora original en inglés con subtítulos en esa misma lengua (n=81) o sin subtítulos (n=92). La muestra incluía un grupo control de hablantes nativos de inglés, además de grupos de hablantes nativos de chino mandarín, coreano y español con inglés como lengua extranjera. Como medidas post-hoc, los participantes reportaron, mediante escalas Likert, su percepción de presencia, transporte, realismo percibido, identificación con los personajes y disfrute. Los resultados muestran que los subtítulos no reducen las medidas de inmersión. Además, que los subtítulos producen mayores puntuaciones de transporte, identificación con los personajes y percepción de realismo, cuya varianza se explica, esencialmente, por la primera lengua de los receptores y sus hábitos de visionado. Asimismo, los resultados señalan que ni a la presencia y ni al disfrute les afectan la condición experimental o el idioma del receptor. Finalmente, muestran que el transporte es la medida más reveladora de la inmersión porque produce las correlaciones más fuertes y consistentes, aparte de ser un predictor significativo del disfrute de los espectadores.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

Cuando vemos una película en cine, o en televisión –en particular, aunque no exclusivamente, una ficción–, nuestra atención es capturada de tal manera que nuestra consciencia acerca del ambiente que nos rodea disminuye o desaparece muchas veces. Vemos televisión o cine porque queremos, o no podemos evitar, estar inmersos en el mundo que se despliega ante nosotros en la pantalla. Por supuesto, este proceso de inmersión no está limitado a los textos audiovisuales (v.g. las películas), sino que también ocurre en el contexto de las narrativas de ficción escritas. Es sabido que las audiencias seleccionan los medios para satisfacer determinadas necesidades, como el deseo de escapar de la realidad, de ser transportadas a otras realidades, de relajarse o de ser entretenidas (McQuail, Blumler, & Brown, 1972). Y, para que las audiencias disfruten de la televisión o de las películas, necesitan estar inmersas o enganchadas en la realidad ficcional creada por la obra audiovisual (Bilandzic & Busselle, 2011; Vorderer, Klimmt, & Ritterfeld, 2014; Sasamoto & Doherty, 2015).

Ahora bien, frecuentemente, las audiencias creen que añadir subtítulos, un elemento adicional textual situado en la parte inferior de la pantalla, estropea la estética de la película o desluce la imagen. No obstante, además de proveer acceso a los textos audiovisuales a audiencias excluidas, sea por el idioma del diálogo o por la imposibilidad de percibir la banda sonora, la subtitulación ha sido considerada como una importante herramienta para el aprendizaje, comprensión y adquisición de competencias idiomáticas (Danan, 2004; Diao & al., 2007; Garza, 1991; Vanderplank, 1988, 1990; Winke & al., 2013). De hecho, en el contexto de las películas de ficción, ha sido establecido que, a pesar de quejas anecdóticas acerca del daño que los subtítulos pueden ocasionar a la imagen, las audiencias procesan los subtítulos efectivamente (d’Ydewalle, Praet, Verfaille, & Van Rensbergen, 1991; Perego, Del-Missier, Porta, & Mosconi, 2010; Perego, Del-Missier, & Bottiroli, 2014).

La inmersión, generalmente, se relaciona con el grado en el que un receptor está absorto en la realidad ficcional. En psicología de los medios, el término es usado frecuentemente en el mismo contexto que el transporte al mundo narrativo o la identificación con los personajes (Green & al., 2004; Tal-Or & Cohen, 2010), aunque también se relaciona con conceptos como presencia, flujo, disfrute (Wissmath, Weibel, & Groner, 2009) o realismo percibido (Cho & al., 2014). La inmersión, de la misma forma que el término relacionado de identificación, es concebida como el producto del transporte al mundo narrativo, la identificación con los personajes, la presencia y el realismo percibido (Bilandzic & Busselle, 2011; Soto-Sanfiel, 2015).

La inmersión en las películas es un estado cognitivo relativamente sensible. Puede, por ejemplo, ser influido por factores externos a la película, como el contexto físico del visionado –en casa, en el cine o mientras viajamos– y el contexto social –en soledad, con familia, con amigos o con extraños–. En esta investigación, estamos interesados, en primer lugar, en si el elemento textual de los subtítulos –que son técnicamente externos a la película, aunque representen el diálogo– tiene un impacto en la inmersión. En segundo lugar, estamos interesados en el impacto del idioma (del espectador, de la película y de los subtítulos) en la inmersión.

A un nivel intuitivo es razonable esperar que la inmersión de las audiencias en una película se vea afectada por la inclusión de subtítulos por la única razón de que la atención visual está dividida. En otras palabras, a diferencia del espectador que ve la película sin subtitular, quien la ve subtitulada debe dividir su atención visual entre la imagen y las palabras de la parte inferior de la pantalla. Cuando un espectador no tiene acceso al audio, o no entiende el idioma del diálogo, depende de los subtítulos para entender la película, por lo que parece existir un sacrificio del objeto de atención. Sin embargo, cuando el espectador tiene acceso al audio y comprende el idioma del diálogo, los subtítulos son una fuente redundante de información. En este caso, el espectador puede usar los subtítulos (en el mismo idioma) para leer conjuntamente con las palabras habladas, particularmente si las últimas no están en su idioma nativo. El espectador puede, por supuesto, ignorar los subtítulos, pero esto no es como suele suceder, según las pruebas empíricas existentes que aseguran que los televidentes leen automáticamente los subtítulos independientemente de si entienden el idioma del audio (d’Ydewalle & al., 1991).

La noción de que los televidentes atienden a los subtítulos automáticamente es respaldada por la investigación en el sentido de interrupciones inesperadas de la atención en la pantalla (Remington, Johnston, & Yantis, 1992). Cuando leen los subtítulos, las audiencias tienen que procesar fuentes adicionales de información verbal y visual que deberían, teóricamente, imponer una carga de procesamiento cognitivo adicional. En palabras de Lee y colaboradores (2013: 414), «las películas subtituladas gravan los sistemas de atención y memoria porque existe tanto información visual (la escena), como información verbal en forma de diálogo escrito además de sonoro». En este estudio estamos interesados en determinar si este procesamiento adicional resulta en un descenso en la inmersión en el mundo representado por la película.

En un trabajo previo (Kruger & al., en prensa), reportamos la primera fase de un experimento diseñado para determinar el impacto de los subtítulos en la inmersión. El material utilizado fue un episodio de un drama americano sobre médicos (House MD) con diálogos en inglés y subtítulos en ese mismo idioma. Participantes ingleses, coreanos y chinos vieron el drama con y sin subtítulos. Esta fase de la investigación fue conducida como un piloto para testar la validez y confiabilidad de diferentes escalas (presencia, transporte, identificación con los personajes y realismo percibido) aparte de para determinar el impacto de las dos condiciones (subtitulada y no subtitulada). Los resultados de este piloto mostraron que no existía un impacto negativo en la inmersión por la percepción de los subtítulos en el mismo idioma en los grupos de participantes mencionados. En este artículo, reportamos una segunda fase del experimento en la que expandimos el tamaño de la muestra y en la que, además, investigamos el impacto de la lengua en la inmersión. Usando un grupo control en inglés, en el presente estudio buscamos determinar si la primera lengua de la audiencia tiene un impacto en la inmersión o si existe una interacción entre el lenguaje y la condición en las distintas escalas de inmersión. También, queremos determinar si las dimensiones de presencia, transporte, identificación con los personajes y realismo percibido están relacionadas, como en los trabajos de Wissmath y otros (2009) y Soto-Sanfiel (2015), además de cómo estas dimensiones se relacionan con el disfrute.

1.1. Subtitulación e inmersión

Los subtítulos compiten por la atención visual y, por tanto, recurren a los finitos recursos cognitivos atencionales para procesar la información visual de los receptores. Sin embargo, los espectadores parecen ser capaces de procesar los subtítulos eficientemente (d’Ydewalle & al., 1991; Perego & al., 2010; Perego & al., 2014). Lee y colaboradores (2013) estudiaron el impacto de los subtítulos en la coherencia local y global. Los investigadores hallaron que se producía menor coherencia global, pero mayor coherencia local con la presencia de subtítulos. Esencialmente, esto significa que la coherencia posibilita la comprensión de la narrativa como una unidad y permite seguir los eventos y los personajes. Sin embargo, los participantes de su investigación que vieron la misma película en un idioma extranjero con subtítulos estándar en su idioma nativo, hacían menos inferencias globales, pero más locales, lo que les permitía tener un mejor sentido de la coherencia local de las escenas a expensas de la coherencia global. Los investigadores concluyeron que los telespectadores que deben cambiar entre leer el diálogo escrito en los subtítulos y la escena tienen una disminución de la habilidad para efectuar inferencias globales debido al hecho de que los recursos cognitivos (incluyendo atención y memorias de trabajo a corto y largo plazo) son grabadas más que en la condición no subtitulada. No obstante, esto podría sugerir también, que existiría un efecto colateral en la inmersión y que esta sería afectada negativamente también por la condición subtitulada. A partir de ello, el contexto de nuestro estudio es la subtitulación en el mismo idioma y en las ocasiones en las que la audiencia no depende de los subtítulos para acceder al diálogo, sino que los subtítulos únicamente confirman ese diálogo de forma escrita. En este sentido, la investigación de Lavaur y Bairstow (2011) sobre el impacto de los subtítulos en la comprensión de la película según la fluidez de los espectadores es particularmente interesante para nuestro estudio. En su trabajo, los investigadores compararon el procesamiento visual y la comprensión del diálogo de espectadores franceses con distintos niveles de suficiencia en inglés (principiantes, intermedios y avanzados) mientras veían una película en inglés sin subtítulos y con subtítulos en inglés o francés. Encontraron que, en los principiantes, el procesamiento visual de la versión con subtítulos en inglés decrecía en comparación con la versión con subtítulos franceses (siendo menor a mayor dependencia de los subtítulos), mientras la comprensión de los diálogos seguía la tendencia opuesta. En otras palabras, para este grupo, la información visual era extremadamente importante para su comprensión. El grupo avanzado tuvo mayor procesamiento visual y comprensión del diálogo en la versión sin subtitulación porque los subtítulos no distraían, lo que indicaba que los subtítulos eran innecesarios para la comprensión. De hecho, el procesamiento de este grupo, y la comprensión de los diálogos, fueron obstaculizados por los subtítulos. El estudio, sin embargo, no observaba ni la inmersión ni el disfrute. La interacción entre la comprensión y la inmersión, o el disfrute, es una pregunta teórica interesante que revisaremos después.

Por su parte, Wissmath y otros (2009) establecieron que la versión subtitulada de una película no resulta en menos inmersión que su versión doblada cuando se mide, mediante auto-reportes, la presencia espacial, el transporte, el flujo o el disfrute. En su estudio, encontraron que los subtítulos en un idioma extranjero (p.ej. el audio doblado en el idioma de la audiencia con subtítulos en el idioma extranjero) redujeron la inmersión, presumiblemente como resultado de la distracción causada por los incomprensibles subtítulos. Igualmente, Perego y otros (2014) establecieron que la versión doblada de una película no ofrece ventajas cognitivas o evaluativas sobre una versión subtitulada de la película en jóvenes o adultos mayores.

Ahora bien, estas contribuciones de Wissmath y colaboradores (2009) y Perego y otros (2014) solo se centran en las diferencias entre las versiones subtituladas y dobladas de las películas. En este estudio, nosotros investigamos el impacto de la presencia o ausencia de subtítulos en el mismo idioma (banda sonora original en inglés con subtítulos en inglés) en la inmersión psicológica y el disfrute. Asimismo, además de las dos condiciones de la película (subtitulada y no subtitulada), investigamos la influencia del idioma en la inmersión mediante el testeo de grupos de participantes hablantes nativos de inglés, chino, coreano y español-catalán con inglés como lengua extranjera. A diferencia de los estudios precedentes, en los que las audiencias no entendían el idioma de los subtítulos o del audio, este trabajo se centra en el impacto de la interferencia visual de subtítulos en la inmersión psicológica y el disfrute, más que en el impacto de las variables vinculadas a la traducción, como la equivalencia lingüística o los cambios en la traducción.

1.2. Midiendo la inmersión

La inmersión mediática o inmersión en los ambientes mediados, como el cine, la televisión o la realidad virtual, es típicamente medida a través de escalas subjetivas auto-reportadas en dimensiones que incluyen presencia, transporte, identificación con los personajes y realismo percibido. En este estudio, usamos las dimensiones de esas variables y, por ello, nos distanciamos del complejo proceso psicolingüístico y sociocultural inter-lingual.

Originalmente denominada tele-presencia, y definida como el sentimiento de los usuarios de dispositivos técnicos de estar localizados en lugares remotos, la presencia es usada especialmente para describir el sentido experimentado por los usuarios de los medios de estar localizados espacialmente en un ambiente mediado (Wissmath & al., 2009). Esa percepción implica el sentido de «estar allí», de haberse marchado o desvanecido del ambiente próximo y de haber llegado, o auto-localizarse, en el ambiente mediático. La percepción de presencia en un ambiente mediado puede referirse a la presencia espacial, a estar localizado en la realidad ficcional o a estar localizado en presencia de personajes ficcionales (presencia social).

Respecto al transporte, y siguiendo a Wissmath y otros (2009), cabe considerar que los aspectos tecnológicos han sido sobre enfatizados en la investigación actual, lo que ha provocado un cambio de énfasis en algunas teorías, como la del transporte, destinado a incluir las características del usuario. El transporte denota que el lector se zambulle en el mundo ficcional mediante la supresión de los hechos del mundo real (Green & Brock, 2000). También, se define como «la experiencia de implicación cognitiva, afectiva e imaginativa en una narrativa de un espectador que ha olvidado su ambiente inmediato». Nótese que el interés de Green y Brock (2000) era, inicialmente, comprender el transporte en la lectura de ficciones, aunque posteriormente lo extendieron al visionado de películas. Según Wissmath y otros (2009), el transporte se solapa conceptualmente con la llamada «voluntaria suspensión del descreimiento» (p.ej., el telespectador, o lector, se permite a sí mismo suspender la conciencia de que lo que ve, o lee, no es real). De todo esto se extrae que, tanto la presencia, como el transporte se relacionan con el grado en el que la audiencia se torna menos consciente de su ambiente circundante.

Tal-Or y Cohen (2010) adaptaron los ítems usados por Green y Brock para medir el transporte auto-reportado de los espectadores de películas. Además, añadieron ítems para medir la identificación con los personajes. Nosotros usamos sus escalas en este estudio como medidas de transporte e identificación con los personajes. Este último fenómeno, la identificación, es muy importante. Permite que los espectadores adopten el lugar de los personajes en la realidad ficcional y asuman su perspectiva. La identificación es un aspecto esencial en la comprensión del entretenimiento mediático y sus efectos, particularmente debido a su influencia en el disfrute narrativo (Cohen, 2001; Igartua, 2010; Soto-Sanfiel & al., 2010). La identificación se relaciona con la afinidad hacia los personajes que experimentan los espectadores (Cohen, 2001), lo que permite que se pongan en los zapatos del personaje. El fenómeno es medido por diversas escalas, como la desarrollada por Igartua y Páez (1998) y refinada por trabajos sucesivos (Igartua, 2010; Soto-Sanfiel & al., 2010). También, existe otra escala propuesta por Cohen (2001). Generalmente, estos trabajos caracterizan a la identificación como un concepto multidimensional formado por la empatía cognitiva, la empatía emocional y la habilidad de fantasear.

Otra dimensión relevante para la inmersión mediática es el grado en el que la audiencia cree que el ambiente mediático de una película es realista. Este concepto ha sido denominado realismo percibido (Cho & al., 2014) y establece el impacto de una narrativa en relación con la persuasión mirando a dimensiones de implicación de la audiencia. Cho y otros (2014) identificaron cinco subdimensiones del realismo percibido:

1) Plausibilidad (¿pueden el comportamiento y los hechos representados ocurrir en el mundo real?).

2) Tipicalidad (¿están las representaciones narrativas dentro de los parámetros de las experiencias pasadas y presentes de las audiencias?).

3) Factualidad (¿parece la narrativa representar a un individuo o hecho propio del mundo real?).

4) Consistencia narrativa (¿son la historia y sus elementos congruentes y coherentes sin contradicciones?).

5) Cualidad perceptiva (¿ofrecen los elementos sonoros y visuales presentes en la narrativa una representación convincente y absorbente de la realidad?).

Al usar las dimensiones de presencia, transporte, identificación con el personaje y las dimensiones del realismo percibido como dimensiones relacionadas, pero diferentes, de la inmersión psicológica, creemos que podemos llegar a una descripción afinada del impacto de los subtítulos en la inmersión de las audiencias en el mundo ficcional.

1.3. Hipótesis

A partir de la revisión de la literatura, y de las preguntas generales de investigación, proponemos las siguientes hipótesis:

• H1. Existirán correlaciones positivas significativas entre todas las escalas de inmersión: transporte, identificación con los personajes, presencia y realismo percibido.

• H2. La condición subtitulada no obtendrá puntuaciones significativamente menores en ninguna de las escalas de inmersión respecto a la no subtitulada.

• H3. El grupo inglés no atribuirá puntuaciones significativamente superiores a ninguna de las escalas de inmersión que los grupos de otros idiomas (chino, coreano y español).

• H4. No existirá interacción significativa entre la condición y el idioma en ninguna de las escalas de inmersión, y

• H5. Se podrá identificar un predictor significativo de disfrute de las escalas de inmersión.

2. Método

2.1. Participantes

Se diseñó y seleccionó una muestra de conveniencia para recoger datos de hablantes nativos de inglés y hablantes de inglés como lengua extranjera, todos estudiantes universitarios. El método fue reproducido exactamente en cada institución participante para incluir variedad de idiomas. Participaron estudiantes de dos universidades en Sídney, Australia (Macquarie University y The University of New South Wales) y una de Barcelona, España (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona). No pusimos ninguna restricción inicial en los idiomas y obtuvimos suficiente números para incluir a todos los que se presentaron a la prueba. La muestra total contenía 173 respuestas válidas de individuos con edades comprendidas entre 18 y 49 (M=25,79, DT=5,84), de los cuales 101 eran mujeres y 74 hombres. Los participantes fueron asignados al azar a una de las dos condiciones de película (subtitulada o no subtitulada). La subtitulada (n=81) estuvo formada por: 23 ingleses, 19 chinos, 13 coreanos y 26 españoles; la no subtitulada (n=92) contuvo 24 ingleses, 22 chinos, 13 coreanos y 33 españoles. En la condición subtitulada los participantes vieron el episodio en inglés con los subtítulos en el mismo idioma, mientras en la no subtitulada vieron el episodio sin subtítulos. Se tomó en cuenta las normas éticas de la investigación con humanos en cada institución participante y se obtuvo consentimiento escrito de ellos. Todos los participantes fueron reclutados mediante correos anónimos y carteles en las instituciones de los autores. La participación fue voluntaria y gratuita. Los datos se recolectaron entre enero y marzo de 2015.

2.2. Materiales

Como estímulo usamos un vídeo de la última temporada de la serie dramática estadounidense de investigación médica House, MD (2011). Para preservar la cohesión y autenticidad, utilizamos el cuarto episodio completo (Negocios arriesgados, 44 minutos). El programa tiene un ritmo de montaje rápido, un alto volumen de diálogos y contiene terminología especializada, además de una fuerte estructura narrativa, lo que lo hace ideal para testar subtítulos e inmersión. Los participantes vieron el episodio en grupos, en un aula de clase, con pantallas amplias y excelente calidad audiovisual (alta definición). Las luces de la sala se apagaron y se solicitó a los participantes que evitasen usar móviles e interactuar con otros participantes durante el experimento, que tomó aproximadamente 90 minutos.

Después de ver la película, los participantes completaron tres juegos de cuestionarios sobre su biografía, idiomas e inmersión. Los datos personales fueron obtenidos mediante un cuestionario biográfico estándar. Los datos de idiomas se obtuvieron con el LEAP-Q, propuesto por Marian, Blumenfeld y Kaushanskaya (2007). Un cuestionario (44 ítems) midió la inmersión usando escalas de Likert de siete puntos (véase Apéndices). El transporte se midió con 10 ítems y la identificación con cuatro, ambos escalados desde «nada» a «mucho» y adaptados de Tal-Or y Cohen (2010), quienes, a su vez, habían adaptado la escala de transporte de Green y Brock (2000). La presencia fue medida con 8 ítems (Kim & Biocca, 1997), que iban desde «nunca» a «siempre». El realismo percibido (Cho & al., 2014) fue medido con 21 ítems escalados desde «nada en absoluto» a «mucho», incluyendo sus sub-escalas: plausibilidad (5), tipicalidad (3), factualidad (3), consistencia narrativa (5) y cualidad perceptiva (5). Algunos ítems se codificaron en reverso. El disfrute, finalmente, fue medido con un único ítem siguiendo estudios que relacionan la presencia y el transporte con él (Green & Brock, 2000; Tal-Or & Cohen, 2010; Wissmath & al., 2009).

2.3. Procedimiento

Un diseño factorial 2x4 entre condiciones (subtitulada, no subtitulada) e idioma (inglés, chino, coreano y español) fue desarrollado sobre las escalas individuales de inmersión (transportación, identificación con los personajes, presencia, realismo percibido, disfrute) usando el procedimiento ANCOVA. En todos los casos se incluyó como covariantes a: los meses pasados en un país de habla inglesa en los últimos diez años, el promedio de consumo televisivo por día y el uso de subtítulos en inglés y otras lenguas.

Todas las variables continuas fueron observadas con el test de Shapiro-Wilk y verificado visualmente su distribución normal. Los meses pasados en un país de habla inglesa, el promedio de consumo televisivo diario y ambas variables de uso de subtítulos no mostraron distribución normal (p>.05), por lo que fueron logarítmicamente transformadas para que alcanzaran este criterio. La fiabilidad de las escalas alcanzó un rango comprendido entre aceptable y bueno: transporte (a=.69), identificación con los personajes (a=.77), presencia (a=.71) y realismo percibido (a=.89).

3. Resultados

3.1. Análisis correlacional

Se hallaron correlaciones positivas significativas entre todas las escalas y con insuficiente evidencia de multicolinealidad. Debido a que las escalas de inmersión muestran una correlación positiva significativa con todas las otras, se afirma la hipótesis 1. Algunas de estas correlaciones son débiles, sin embargo, especialmente entre presencia y el resto de las escalas (tabla 1).

3.2. Transporte

La escala muestra un rango total posible de 10-70. El ANCOVA de dos factores no encontró interacción significativa entre condición e idioma en este factor [F(3, 160)=. 654, p=.582, ?p2=.012]. No obstante, se halló efectos principales significativos en condición [F(1, 160)=8.550, p=.004, ?p2=.051]. La condición subtitulada fue mayor, aunque no para lenguaje [F(3, 160)=2.431, p=.065, ?p2=.044], como muestra la tabla 2.

3.3. Identificación con los personajes

La escala muestra un rango posible total de 4-28. El ANCOVA de dos factores no encontró interacción significativa entre la condición y el idioma en la identificación [F(3, 160)=.299, p=.826, ?p2=.006]. Ahora bien, fueron hallados efectos principales significativos para condición [F(1, 160)=11.896, p=.001, ?p2=.069] e idioma [F(3, 160= 4.065, p=.008, ?p2=.071]. La condición subtitulada fue mayor (tabla 2). Para idioma, un test de Tukey post-hoc con ajustes Bonferroni y comparaciones múltiples mostró que la identificación del grupo inglés era significativamente mayor que la del coreano (p=.008) y la deespañol (p=.013).

3.4. Presencia

La escala muestra un rango posible de 8-56 en total. El ANCOVA de dos factores no encontró interacción entre condición e idioma [F(3, 160)=1.532, p=.208, ?p2=.028] (tabla 3). Este también fue el caso de los efectos principales para condición [F(1, 160)=1.330, p=250, ?p2=.008] e idioma [F(3, 160)=2.699, p=.051, ?p2=.048].

3.5. Realismo percibido

La escala muestra un rango posible de 21-147 en total. El ANCOVA de dos factores encontró interacción significativa entre condición e idioma [F(3, 160)=3.782, p=.012, ?p2=.066]. La condición subtitulada fue mayor (tabla 4). Se encontraron también efectos principales significativos en el promedio de consumo de televisión por día [F(1, 160)= 4.003, p=.047, ?p2=.024] y en el uso de subtítulos en otros idiomas [F(1, 160) =6.361, p=.013, ?p2=.038]. Para idioma, un test post-hoc de Tukey con ajustes Bonferroni para comparaciones múltiples mostró significación en: inglés mayor que chino (p=.009), coreano (p<.001) y español (p<.001). También, chino fue mayor que coreano (p=.007) y español (p=.02).

3.6. Disfrute

La escala muestra un rango posible de 1-7 porque consta de un solo ítem. El ANCOVA de dos factores no encontró interacción entre condición e idioma en el disfrute [F(3, 160)=.654, p=.582, ?p2=.012] (tabla 3). Los efectos principales por condición [F(1,160)= 2.086, p=.151, ?p2 =.013] e idioma no fueron significativos [F(3, 160)= 2.214, p=.458, ?p2=.016].

En suma, encontramos suficiente evidencia a favor de que la versión subtitulada resultó tener menores niveles de inmersión, lo que confirma la hipótesis 2. Contrariamente a lo esperado, la versión subtitulada resultó en mayores niveles de transporte e identificación con los personajes. También, hallamos diferencias en la inmersión entre los grupos de idiomas, lo que rechaza parcialmente la hipótesis 3 porque el grupo de inglés reportó mayores niveles de identificación y realismo percibido que los de otros idiomas. Nótese, no obstante, que transporte, presencia y disfrute eran similares para todos los grupos de idiomas. Finalmente, rechazamos la hipótesis 4 porque los grupos de inglés y chino reportaron niveles significativamente más altos de realismo percibido mientras que en las otras escalas sus puntuaciones eran similares.

3.7. Predicción de disfrute

Un análisis de regresión múltiple con el método Enter fue conducido para identificar los predictores significativos de disfrute tomando en consideración las covariaciones identificadas: meses en un país de habla inglesa, consumo promedio de televisión por día y uso de subtítulos en inglés y otros idiomas. Se halló independencia de residuales, como mostró el valor de Durbin-Watson (1,623) y se cumplieron los supuestos de linealidad, homocedasticidad y normalidad. No se halló evidencias de multicolinealidad, influencia o potencia.

El modelo [F(8, 163)=4.772, p<.000, adj. R2=.15] mostró que el transporte era el único predictor significativo de disfrute (tabla 4) y que este factor explicaba mayor cantidad de la varianza de disfrute que ninguna de las otras escalas de inmersión. Porque el análisis de regresión múltiple identificó solo el transporte como un predictor significativo de disfrute, obtenemos suficiente evidencia para confirmar la hipótesis 5, aunque el hecho despierta preguntas acerca de la relación entre disfrute y otras medidas de inmersión.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Este estudio contribuye a la comprensión del papel que los subtítulos tienen en los procesos relacionados con la inmersión psicológica en las narrativas fílmicas. En particular, este estudio añade información sobre la relación entre el idioma de los subtítulos y el receptor en la predicción de inmersión y disfrute, lo que no había sido observado antes.

Nuestros resultados muestran que la versión subtitulada no resultó en la inmersión significativamente inferior en ninguna de las escalas, ni por el grupo de percepción como un todo, ni por los grupos de idiomas específicos. Esto demuestra que los subtítulos no actúan como distracción para las audiencias, aunque sea en el mismo idioma de la representación. Así pues, añadir subtítulos no dificulta a las audiencias la inmersión en la realidad ficcional. Más que como un elemento extradiegético, los receptores procesan los subtítulos como parte del mundo de la historia en una forma similar al procesamiento del diálogo sonoro.

En el examen de las escalas de inmersión, es interesante destacar que los subtítulos resultaron en mayor transporte, identificación con los personajes y realismo percibido. Esto provee evidencia a favor de que los subtítulos facilitan la habilidad de las audiencias para sentirse envueltas en el mundo de la historia y situarse, ellas mismas, en la posición de los personajes.

En este trabajo también estábamos interesados en el papel del idioma de la audiencia en el impacto de los subtítulos en la inmersión. Sobre ello, no encontramos interacción entre la condición y el idioma en las escalas de transporte, identificación o presencia, aunque en el caso de la identificación con los personajes, el grupo inglés reportó un grado significativamente mayor de identificación que los grupos de inglés y español. Esta diferencia tendrá que ser investigada en profundidad con la ayuda de datos históricos sobre la relación con el idioma. Por otra parte, se halló una interacción significativa entre el idioma y la condición en la escala de realismo percibido.

Asimismo, en este trabajo buscábamos comprender la relación entre las diferentes escalas en la medición de inmersión. El transporte tuvo la mayor correlación con las otras escalas, lo que parece sugerir que este factor es de especial valor en la medida de inmersión en el contexto de la traducción audiovisual. Considérese también que la correlación más fuerte se halló entre transporte e identificación con los personajes. Además, que, aunque no se halló interacción entre idioma y condición en términos de disfrute, el transporte resultó el único predictor de disfrute.

Todos estos hallazgos parecen sugerir que la combinación de transporte con identificación con los personajes provee la medida más clarificadora de la inmersión en el contexto de traducción audiovisual. Tal-Or y Cohen (2010) definieron, la identificación y el transporte como dos de los mayores conceptos usados para describir la implicación de las audiencias en el entretenimiento y que son procesos distintos. Por ello, el hecho de que los subtítulos cumplan un efecto de focalización, más que distanciar la audiencia de la realidad ficcional y de los personajes, muestra que sirven para ganar una mayor conexión con la historia.

Por otra parte, esperábamos que los covariantes identificadas tuvieran un papel más marcado en el proceso de inmersión. Sin embargo, únicamente en el realismo percibido, el consumo promedio de TV y el uso de subtítulos impactaron significativamente.

En conclusión, en el contexto de este particular drama, organizado en torno a diálogos y caracterizado por un lenguaje rápido, terminología médica y una potente narrativa, los subtítulos en el mismo idioma inglés provocan un incremento de la inmersión, en particular en las dimensiones claves de identificación y transporte. Este resultado disipa las preocupaciones acerca de que los subtítulos distraen a las audiencias. De hecho, en este contexto, los subtítulos parecen focalizar la atención y permitir a las audiencias confirmar visualmente los diálogos complicados.

4.1. Limitaciones

Se encuentran en el número de idiomas cubiertos y en la forma superficial con que se midió la suficiencia del idioma. El testar la inmersión con idiomas adicionales y obtener información más profunda sobre la competencia lingüística de los receptores ofrecerá más claridad sobre el problema. Además, se requiere observar la inmersión en distintos géneros audiovisuales para que nuestros resultados sean más generalizables. Podría suceder, por ejemplo, que los fuertes efectos encontrados en el caso del transporte y la identificación sean menos marcados en géneros que descansan más en los efectos visuales y la acción. Así, podría existir división de atención entre el diálogo y los movimientos visuales rápidos, lo que afectaría la inmersión.

Finalmente, creemos necesario tomar en consideración la propia interacción de los individuos con la inmersión, para lo que el uso del cuestionario de tendencias inmersivas sería recomendable. En este estudio, sin embargo, se añadieron 13 ítems y se priorizó la focalización en las variadas escalas de inmersión. Basados en nuestros resultados, y dependiendo, por supuesto, de las preguntas de investigación y su contexto, futuros estudios podrían usar dicho cuestionario en combinación con las escalas de transporte y disfrute.

Referencias

Bilandzic, H., & Busselle, R.W. (2011). Disfrute of Films as a Function of Narrative Experience, Perceived Realism and Transportability. Communications, 36(1), 29-50. (http://goo.gl/zSFKs7) (2016-05-31).

Cho, H., Shen, L., & Wilson, K. (2014). Perceived Realism: Dimensions and Roles in Narrative Persuasion. Communication Research, 41(6), 828-851. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212450585

Cohen, J. (2001). Defining Identification: A Theoretical Look at the Identification of Audiences with Media Characters. Mass Communication Society, 4(3), 245-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01

Danan, M. (2004). Captioning and Subtitling: Undervalued Idioma Learning Strategies. Meta, 49, 67-77. https://doi.org/10.7202/009021ar

Diao, Y., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2007). The Effect of Written Text on Comprehension of Spoken Inglés as a Foreign Idioma. The American Journal of Psychology, 120(2), 237-261. (http://goo.gl/v3QhbZ) (2016-05-31).

D’Ydewalle, G., Praet, C., Verfaillie, K., & Van Rensbergen, J. (1991). Watching Subtitled Television: Automatic Reading Behavior. Communication Research, 18, 650-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323102017003694

Garza, T.J. (1991). Evaluating the Use of Captioned Video Materials in Advanced Foreign Idioma Learning. Foreign Idioma Annuals, 24(3), 239-258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1991.tb00469.x

Green, M. C., & Brock, T.C. (2013). Transport Narrative Questionnaire. Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Science. (http://goo.gl/2REoeG) (2016-05-31).

Green, M.C., Brock, T.C., & Kaufman, G.F. (2004). Understanding Media Disfrute: the Role of Transportation into Narrative Worlds. Communication Theory, 14(4), 311-327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00317.x

Igartua, J.J. (2010). Identification with Characters and Narrative Persuasion through Fictional Feature Films. Communications. The European Journal of Communication Research, 35(4), 347-373. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2010.019

Igartua, J.J., & Páez, D. (1998). Validez y fiabilidad de una escala de empatía e identificación con los personajes. Psicothema, 10(2), 423-436. (http://goo.gl/W3vssl) (2016-05-31).

Kim, T., & Biocca, F. (1997). Telepresence via Television: Two Dimensions of Telepresence may have different Connections to Memory and Persuasion. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00073.x

Kruger, J-L., Soto-Sanfiel, M.T., Doherty, S., & Ibrahim, R. (forthcoming). Towards a Cognitive Audiovisual Translatology: Subtitles and Embodied Cognition. In R. Muñoz-Martìn (Ed.), Reembedding Translation Process Research (pp. 171-194). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lavaur, J.M., & Bairstow, D. (2011). Idiomas on the Screen: Is Film Comprehension related to Viewers’ Fluency Level and to the Idioma in the Subtitles? International Journal of Psychology, 46(6), 455-462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.565343

Lee, M., Roskos, B., & Ewoldsen, D.R. (2013). The Impact of Subtitles on Comprehension of Narrative Film. Media Psychology, 16(4), 412-440. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.826119

McQuail, D., Blumler, J.G., & Brown, J.R. (1972). The Television Audience: A Revised Perspective. In D. McQuail (Ed.), Sociology of Mass Communication (pp. 135-165). Middlesex, UK: Penguin.

Perego, E., Del-Missier, F., & Bottiroli, S. (2014). Dubbing versus Subtitling in Young and Older adults: Cognitive and Evaluative Aspects. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 23(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2014.912343

Perego, E., Del-Missier, F., Porta, M., & Mosconi, M. (2010). The Cognitive Effectiveness of Subtitle Processing. Media Psychology, 13(3), 243-272. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2010.502873

Remington, R.W., Johnston, J.C., & Yantis, S. (1992). Involuntary Attentional Capture by Abrupt Onsets. Perception and Psychophysics, 51(3), 279-290. (http://goo.gl/5KRgy0) (2016-05-31).

Sasamoto, R., & Doherty, S. (2015). Towards the Optimal Use of Impact Captions on TV Programmes. In M. O’Hagan, & Q. Zhang (Eds.), Conflict and Communication: A Changing Asia in a Globalising World (pp. 210-247) Bremen, Germany: EHV Academic Press.

Soto-Sanfiel, M.T. (2015). Engagement and Mobile Listening. International Journal of Mobile Communication, 13(1), 29-50. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijmc.2015.065889.

Soto-Sanfiel, M.T., Aymerich-Franch, L., & Ribes, F.X. (2010). Impacto de la interactividad en la identificación con los personajes. Psicothema, 22(4), 822-827. (http://goo.gl/kvrJzc) (2016-08-11).

Tal-Or, N., & Cohen, J. (2010). Understanding Audience Involvement: Conceptualizing and Manipulating Identification and Transportation. Poetics, 38: 402-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2010.05.004

Vanderplank, R. (1988). The Value of Teletext Sub-titles in Idioma Learning. ELT Journal, 42(4), 272-281. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/42.4.272

Vanderplank, R. (1990). Paying Attention to the Words: Practical and Theoretical Problems in Watching Television Programmes with Uni-lingual (CEEFAX) Sub-titles. System, 18(2), 221-234.