(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== In th...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 396736247 to Gomez-Espinosa et al 2016a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 17:35, 27 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

In this work we aim to gain a better understanding of the nature of plagiarism in Higher Education. We analyse a set of different activities in an online university-level course, aiming to understand which tasks lead more naturally to plagiarism. This analysis concludes that the activities that have a lower rate of plagiarism are activities that encourage involvement, originality and creativity. Subsequently, we reformulate the task that presented the highest rate of plagiarism, taking into account the conclusions of the previous analysis and trying to maintain their relative effort and educational impact. We then compare the newly designed activities with their original counterparts to measure whether there is a significant reduction in plagiarism. The results are clear and show a significant drop in the percentages of plagiarism. In addition, we performed an additional validation to ensure that both groups were, in fact comparable. We found that both groups displayed similar plagiarism attitudes in other exercises that were not reformulated. This study shows that it is possible to reduce the incidence of plagiarism by designing activities in such a way that prompts students to propose their own ideas using information available on the Internet as a vehicle for their solutions rather than as solutions in themselves.

1. Introduction

Academic plagiarism is, unfortunately, a common and widespread issue at all levels. Beyond the most typical cases from young students, it is easy to find high-profile examples of plagiarism reported even in mainstream media. In recent years we have witnessed the resignation of two German ministers accused of plagiarizing in their doctoral theses (Eddy, 2013). And while the problem is not new, the revolution in how we search and process content brought by the Internet has increased the challenge in educational settings. Students are prompted to produce and deliver exercises, essays or solutions to problem statements, and find all this information just a few clicks away (Atkins & Nelson, 2001; DeVoss & Rosatti, 2002; Moore, 2007). In this work we aim to gain a better understanding of the nature of plagiarism, especially in those cases where it is not due to an excessively complicated task.

1.1. Plagiarism in Higher Education

The Internet has entered all aspects of our daily life, including university classrooms, and a new way of approaching assignments has emerged. Many students seek the fastest possible solution to classroom assignments, regardless of the validity of the sources or respect to the work of others, a phenomenon that is widespread across all educational levels (Sureda, Comas, & Oliver, 2015). In this case, our focus is on Higher Education, where the growth of plagiarism has been an ongoing concern over the past few years (Culwin & Lancaster, 2001; Hart & Friesner, 2004; Clegg & Flint, 2006; Ellery, 2008; Eret & Gokmenoglu, 2010; Bretag, 2013; Heckler & Forde, 2015), and in which teachers are increasingly worried about the frequency and apparent lack of awareness of its moral implications by students (Perry, 2010).

The results of a survey conducted by the companies Six Degrés (2008) and Le Sphinx Développement showed some significant behaviors of students and teachers, identifying the Internet as the main source of documentation (90%) and with 43% of the students reporting that never or seldom cited their sources. These results were consistent with another experiment administred to 1,025 students (Comas, Sureda & Oliver, 2011) which states that 7 out of 10 university students admitted to copy texts or fragments of texts for the development of their academic activities, presenting them as their own.

Other studies conducted in different environments show widespread use of unethical practices, but introduce nuances. The University of La Rioja (Spain) in 2011-12 conducted an empirical experiment analysing 104 assignments from a university-level degree in Business Management. The students had to submit different assignments during the course, as well as a high-stakes final essay. Among the documents submitted, 13 of them (12.5%) displayed a plagiarism rate higher than 40%, a figure far beyond what could be considered academically reasonable. Remarkably, the higher the stakes in the activity, the lower percentage of plagiarism was found, suggesting an interesting link between the perceived importance of the task and the tendency to plagiarize (Gómez, Vargas, & Salazar, 2012). Regarding the attitude of the students towards plagiarism, a recent study by Newton (2015) pointed out that students considered that «academic misconduct should be modestly penalised», and only developed stricter attitudes after graduation.

Regarding the factors that invite students to plagiarise, even before the Internet was available, Ashworth, Bannister and Thorne (1997) identified four key issues: 1) The lack of awareness by the students concerning whether they are doing plagiarism or not; 2) The low probability of being detected; 3) the pressure on the level of demand and the deadlines established for the works; 4) The actual wording of the activities provided by teachers. These factors are still relevant: A more recent study by Eret & Ok (2014) observed that the tendency to plagiarize is, in fact, increasing with the spread of the Internet, and pinpointed as main reasons for plagiarism time constraints, excessive workloads and high difficulty of the proposed assignments. These results are consistent in terms of reasons for plagiarism with the findings from Chen & Chou (2014) in a local study focusing on Taiwanese students. Another recent study from Hussein, Rusdi, & Mohamad (2016) found that students were widely aware of what plagiarism is, and that it is inappropriate. However, this would not deter students from plagiarizing for the other reasons mentioned. A more directed study from Kauffman & Young (2015) looked into how the ease of access to copy&paste tools and the presentation of the tasks influenced attitudes towards plagiarism.

In summary, most studies coincide in the interpretation that access to information has become so immediate that it is perceived by some as a «common knowledge» available for everyone to reproduce (Walker, 2010). These widespread issues have led to an academic/technological response seeking new ways and tools to detect plagiarism, as outlined in the next section.

1.2. Plagiarism detection tools

Many institutions approach the problem of plagiarism from the use of different methods to detect infringements. Such methods may range from the very simple (e.g. reverse-searching on Google, or any other general search engine) to the use of complex tools that perform more thorough checks.

Some tools automate the process of reverse-checking. Two of the most commonly cited tools in this category would be Plagiarism Checker (http://goo.gl/kElH) and Article Checker (http://goo.gl/GgYtQ). Also in this category are CopioNIC (https://goo.gl/KQL9Ru), a free web application (requiring registration), that allows uploading files for search and Magister by Compilatio.net (https://goo.gl/FqnPHb) that allows both students and staff to upload documents and check their results online.

On the other hand, there are also products that create their own databases in which teachers can find the most interesting resources. Two examples could be Viper Plagiarism (http://goo.gl/TrBey) and Turnitin (http://goo.gl/ixhp9). The latter is one of the most widely used resources in the academic world, and compares new works with a large database of academic and web content, and its dominant position could grow to their recent merger with Ephorus (https://goo.gl/PifnGN), which is also present in many Higher Education Institutions. These tools are competing with other systems such as CrossCheck (http://goo.gl/DFB0vQ), which was originally created for scholarly articles, but is becoming another reference tool also for plagiarism detection in educational settings.

This thriving marketplace of plagiarism detection tools is apparently mature enough for detecting plagiarism not to be challenge. However, plagiarism cases remain common, even in situations where students are aware of the existence of these tools. Part of the problem may be related to the limitations of these tools, as identified by Vallejo (2011), including the fact that students may try to «trick» these tools, language limitations or an excessively burdensome process. Without ignoring the power of these tools, we argue that they are only part of the solution. It is important to complement these systems with changes in the methodology and with the promotion of good practices, looking for honesty and academic integrity.

2. Material and methods

The main objectives of this work are to gain a better understanding of why students plagiarize and to study whether changes in the presentation of academic assignments can have an impact in the rates of student plagiarism. The study was therefore organized in two stages: (1) a preliminary study to detect which tasks in an existing course presented higher levels of plagiarism and (2) a specific intervention aimed at reducing the rate of plagiarism among the students in those activities where plagiarism was more common.

The hypothesis is that it would be possible to reduce plagiarism by changing the presentation and statement of the activity, while maintaining the relative effort and educational design intact.

2.1. Target course and student populations

This research has been conducted in the context of the course «Mathematics - Complementary course», which is part of an Official Master’s Degree in Elementary Education offered in a fully online modality at International University of La Rioja (UNIR). The assessment of this course is performed according to criteria set by the Bologna Process, trying to increase the importance of coursework activities vs. a final high-stakes exam. The course adopts a hybrid evaluation model in which the final qualification is composed of two parts: 60% corresponds to the in-person final exam; 40% is obtained from scores on a set of coursework activities presented by the student throughout the semester. Students are offered a wide set of activities and need to score 4 points in total. The maximum score of all combined activities is in fact 6 points, and students can therefore choose to focus on particular activities and are not forced to complete all of them.

Two student cohorts from the same course were taken into account in the two stages of this study:

• Group A: 65 students enrolled in the 2011-12 academic year.

• Group B: 94 students enrolled in the 2012-13 academic year.

The students from Group A were the base for the preliminary study to detect how plagiarism affected the different assignments during the course. Then, after designing the specific intervention, these students were considered as the control group, while students in Group B were considered as the experimental group.

2.2. Background study: identifying and understanding plagiarism in an online course

As mentioned above, the first step in this research was to study the activities proposed for the continuous assessment of a course throughout the academic year, taking into account the rates of plagiarism. Students participated online through a virtual classroom, where all the activities and their corresponding maximum scores were provided. These were the activities proposed to students to earn the required 4 points of continuous assessment:

• Self-assessment quizzes: 14 self-assessment quizzes, with multiple-choice questions are offered, one for each of the lessons in the course, with a value of up to 0.05 points per each test.

• Attendance at online meetings: Attending at least two classroom meetings is assessed with 0.15 points.

• Participation in discussion forums: The forums request contributions and discussions among the students. The student may earn a maximum of 0.5 points, and the rating takes into account the number of interventions and their quality and relevance.

• Open ended assignments: These assignments include activities such as creating a glossary of mathematical terms, a study of geometry, statistical analyses, etc. There are different assignments, with values ranging from 0.5 points to 1 point each.

• Readings and personal proposals: Reading assignments focus on review articles, newspaper pieces, etc. and make a personal reflection. The student may earn a maximum of 1 point with each activity.

To develop our baseline study, we sampled the behaviour of the students in Group A (2011-12) to understand their participation rates and plagiarism trends.

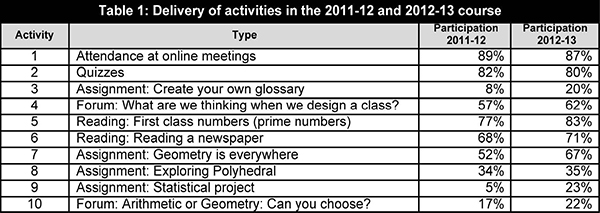

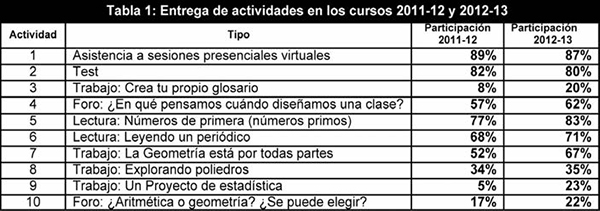

2.2.1. Understanding student participation

As mentioned in section 2.1, students are not required to participate in all tasks. Each student can decide to focus on different assignments while ignoring others. In order to focus our effort on specific activities, we started by studying participation rates in the 10 possible assignments. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the delivery rates for each activity in the course. Although the preliminary study focused on Group A (2011-12), participation rates from Group B are also provided for comparison.

The activities that typically present a higher participation rate are the quizzes and attending online meetings. The relative simplicity of these activities and the flexibility for delivering them over the entire term may be two of the reasons that make their delivery rate so high. While these activities are not prone to plagiarism, they remain the most popular among students.

In turn, assignments and readings have varied results, with yield rates diminishing as the course advances and the difficulty increases. Activities 3 and 9 have very low rates and this may be due, primarily, to the fact that both activities involve searching across a variety of information sources, which involves a greater investment of time in completing the task.

2.2.2. Analysis of plagiarism

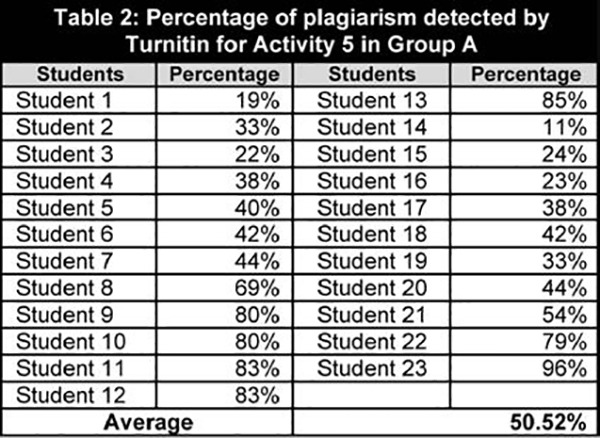

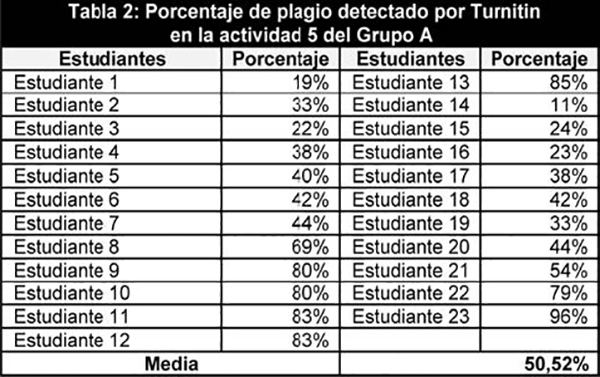

For this task, we ignored Activities 1 and 2, since they do not involve any production process by the students. In total, students submitted more than 350 activities during the year 2011-12. Given the time limitations faced during the course, we selected a random sample to assess plagiarism rates (up to 23 deliveries per task). The selection was performed randomly for each task, given that the specific students that choose to submit each of the assignments are different. In those activities where the total yield was lower, we included all the exercises delivered. All these activities were analysed using the Turnitin anti-plagiarism tool. The results are presented next grouped by activity.

• Forums: Among the activities submitted on the two forums, 36.36% included plagiarism. Although the percentage is not high, the kind of plagiarism was very serious, as it is an activity in which the task explicitly requested personal opinions.

• Open ended assignments: Activity 9 on creating a statistical project was only delivered by three students. It is noteworthy, nevertheless, that two of them are completely original, but the third presented a plagiarism rate of 31%. Activities 3, 7 and 8 have particular characteristics, as they ask for descriptions of mathematical content and therefore it is common to use classical definitions, commonly accepted and displayed on many pages across the Internet.

• Readings and personal proposals: In Activity 6 plagiarism was not detected in any case. It is an activity that seeks to analyse the data from a current newspaper locating the various numbers and mathematical concepts that appear in it. Students chose all kinds of newspapers, focusing either on general news or specific topics, and the presentation of this activity was also varied delivering the data in both schematic tables and in more developed reports.

In turn, Activity 5 displayed much worse results. All samples (100%) presented matches with uncited or improperly cited sources (table 2). Seven of these activities (30.4%) included a plagiarism rate above 80%, with the worst case reaching 96%. Only five of the pieces of work analysed returned percentages below 25%.

2.2.3. Preliminary results

Data analysis shows that Activity 5 has the highest rate of plagiarism, combined with the highest participation rate after excluding quizzes and attending online lectures. It is so high that the blame cannot be attributed exclusively to the students who had not resorted to plagiarism in such a high proportion in the other activities. Remarkably, this activity focuses on a very specific topic, easy to look up on the Internet, barely related to news items and with very few direct applications in the classroom.

After careful analysis, and regardless of the unethical approach from some students, we have to consider the instructional design of the activity as flawed since it is eliciting such behaviour in wide populations of students that seemed capable of delivering original works in other assignments. In contrast, the effort required for the activity does not seem to be a determining factor in increasing plagiarism, since the activity that requested an analysis of the numerical elements of a newspaper was also a high-workload long task and had low rates of plagiarism.

Having reviewed the various activities proposed and their characteristics, it can be seen that those which have a lower rate of plagiarism are the ones that imply a more personal involvement of the students with opinions and suggestions, as well as those in which the contents are linked to elements present in everyday life and closer to the student environment. In summary, in activities that encourage involvement, originality and creativity. From these preliminary conclusions, we endeavour to check whether changes in the design (but not the deep meaning) of an activity can have an impact in plagiarism rates.

2.3. Intervention design

In this section the design of the experiment to reduce plagiarism is presented: after identifying the activity that had displayed the highest rate of plagiarism, this activity was redesigned and presented to a new student population (Group B). These students (n=94) were enrolled in the 2012-13 academic year, in the same course with the same agenda, planning, sequencing and evaluation.

2.3.1. Redesign of activity 5

Activity 5 was selected for the analysis of the hypothesis. The original design of the activity was in the form of an open text question with the implicit goal of having the students to present a report with appropriate data in such a way that they could be used in a primary school syllabus. The statement of this activity was as follows (translated from Spanish):

- Reading: First class numbers: In the recommended reading for this chapter, the Devil of Numbers introduces Robert to some special numbers: those he was calling first class numbers. In the real world these numbers are called prime numbers and as our protagonist says «Mathematicians have spent over a thousand years puzzling over them. They are wonderful numbers. For example eleven, thirteen or seventeen...». Research the meaning of prime numbers and write a short essay presenting the key ideas about these numbers (definition, historical development, properties, curiosities...).

During the 2012-13 academic year, the title and task briefing for the activity were modified, following some guidelines seeking to avoid plagiarism among students, according to the conclusions from preliminary study section. For this purpose, the activity was presented to students as follows:

• Reading: Explaining what first-class numbers are: In the recommended reading for this chapter the Devil of Numbers introduces Robert to some special numbers: those he used to call first class numbers. In the real world these numbers are called prime numbers and as our protagonist says «Mathematicians have spent a thousand years puzzling over them. They are wonderful numbers. For example eleven, thirteen or seventeen...». Research prime numbers, then we propose the following activity: Imagine you in front of a class of children between 9 and 10 years, to whom you have to explain briefly what the prime numbers are. Write half a side of paper (no more than 30 lines), on how would you explain it. If you wish, you may also add a picture or a diagram in the lower half of the sheet. Try to make it fun, original, educational, etc., remember that you are explaining it to children!

• Activity objectives: Be aware of the relevance for Mathematics of the primes; assume the role of teacher preparing (schematically) a class for elementary students; Design a motivating activity relevant to your future career as a teacher.

• Criteria for assessing the activity: The concepts presented and explained about prime numbers and their properties must be correct; the level of originality and creativity in the development of the class will be valued; Suitable writing and spelling.

The new design of the activity gives specific guidelines including the need to develop the activity for a real and relevant environment (Primary classroom). The activity is presented as a small piece of research which proposes data search, but requesting delivery of a personal proposal, which seeks student creativity, and not a mere list of the data found. The evaluation criteria explicitly present how to use the supporting materials and how the rigor and clarity of the content posted will be considered. With the new design of the activity, the student is aware that creativity will be assessed, but also is aware of the importance of correctness of the data provided. Most importantly, the evaluation rubric, expected completion time and delivery date remained equal to the original activity, only the task briefing changed.

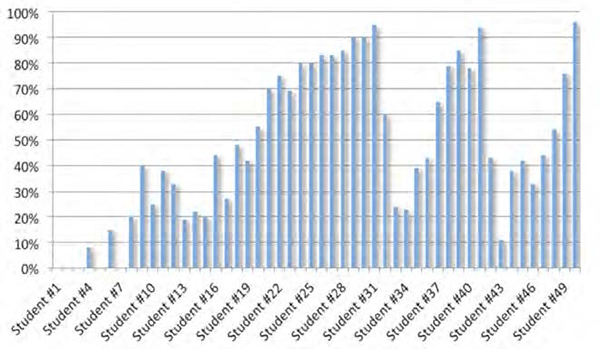

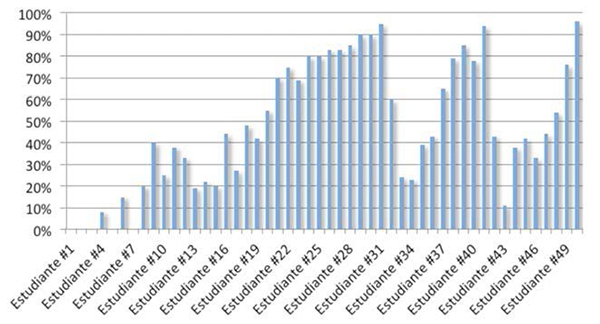

Figure 1. Plagiarism rates in the control group.

2.3.2. Experimental design

The redesigned activity will be presented to students in the next academic year for comparison. Students from the 2011-12 academic year (Group A) will be considered as the Control Group, while students from the 2012-13 academic year (Group B) will be considered as the Experimental Group. Once the course is completed, two important measurements will be taken:

• Measurement #1: An in-depth comparison of plagiarism rates in Activity 5, in order to understand whether the new design resulted in lower plagiarism rates. The plagiarism rates for each group will be analysed and compared using t-test comparisons to check whether there is a statistically significant variance in plagiarism rates.

• Measurement #2: A comparison among the two groups in other activities, to study whether the two groups were truly comparable in their day to day plagiarism practices and in their general performance. This second measurement is important in order to discard significant differences among the two groups (e.g. the experimental group may happen to be initially formed by students with stronger ethical principles in terms of plagiarism).

Figure 2. Plagiarism rates in the experimental group.

3. Results

While Group B was larger than Group A, their relative submission rates were reasonably similar, as observed previously in table 1. The two most notable exceptions were activities 3 and 9. Most relevantly, the average submission rate of activity 5 over the two academic years is over 75%. Despite the change in the design of the activity no significant changes were seen in the participation rate, maintaining a high percentage of submission.

3.1. Plagiarism rates (measurement #1)

The first step was to perform an in-depth analysis of all the deliveries of activity 5 in both courses. In total, there had been 50 submissions in the control group (Group A) and 78 deliveries in the experimental group (Group B), given that students are not required to submit all assignments. Figures 1 and 2 indicate the plagiarism rate found in each exercise submitted by both groups. The results are remarkable, with very few students in the experimental group displaying any rate of plagiarism, and only two isolated cases displaying rates above 30%.

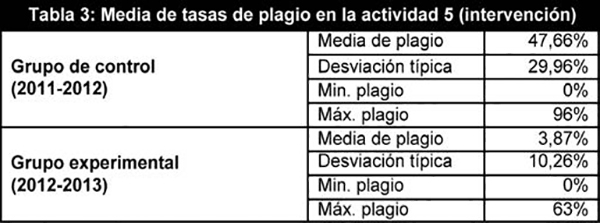

As a result, as can be seen in table 3 the average plagiarism in the experimental group (M=3.87, SD= 10.26) is much lower than the rate displayed by the control group (M=47.66, SD=29.96). This difference was found to be statistically significant, t (56.4= 9.97, p<.000, d=4.39). Levene’s test for equality of variances was found to be violated, and therefore a t-test not assuming homogeneous variance was calculated.

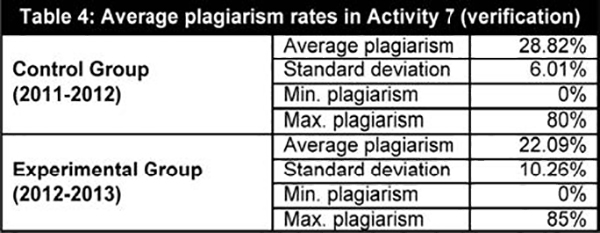

3.2. Performance comparison (measurement #2)

While the analysis from plagiarism rates shows a significant improvement in the plagiarism rates, it was important to address whether both groups were truly comparable, trying to reduce any potential confounding factors. This was especially relevant given that the staff do not have access to demographic data from their student cohorts.

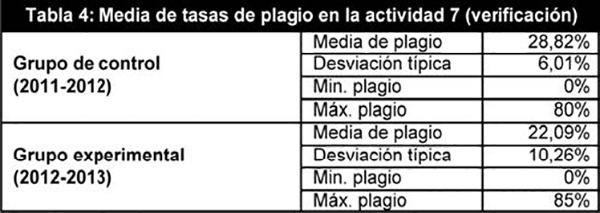

In table 1 it could be observed that the submission rates were reasonably aligned. In addition, we have also studied their performance in another activity to ensure that the two groups were certainly comparable. We have analysed the results for the activity with the second highest rate of coincidences, Activity 7, in which students must select a photograph and analyse mathematical elements that appear in it. This activity had a high degree of overlap, from multiple sources, usually without references, from which the students extract the definitions that accompany the photographs.

In this case, as observed in table 4, the experimental group performed slightly better (M=22.09, SD=6.24) than the control group (M=28.82, SD=6.01), a difference of only 6.73% that was found to be not significant during the statistical analysis.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Based on the growing interest that plagiarism is receiving in Higher Education contexts, this work has focused in understanding why and how students plagiarize, and in exploring constructive approaches to reducing plagiarism.

We started with a study of plagiarism patterns in an online Master’s degree, observing and discussing how each type of assignment resulted in different plagiarism rates. In this preliminary study, we identified which tasks were more prone to plagiarism and tried to alleviate this situation by trying to promote an internal motivation to be creative, as opposed to increasing the severity of our potential coercive methods. This resulted in our main experiment, in which we changed only the instructions of the assignment, but neither the purpose of the task nor the evaluation rubric.

The results present a very obvious difference between the experimental group and the control group, indicating a very strong effect of how the exercise was worded. This indicates that the approach taken by staff had a profound impact in the students’ attitude towards the exercise.

We believe that it is especially remarkable that the students did not receive any especial threats warning against plagiarism other than the usual that all groups receive at the beginning of the course. This contrasts with many of the existing perceptions about why students would cheat: laziness, difficult tasks, lack of understanding of the moral implications, etc. In this test, we ellicited a positive response from our students substituting the usual approach (threats of consequences if caught cheating) with a proposal that dared them to be creative and original.

This study therefore shows that it is possible to reduce the incidence of plagiarism by designing activities in such a way that students are prompted to propose their own ideas, and in which they approach the search for information already available on the Internet as a vehicle for their solutions, but not the main task. It should be noted, however, that this experiment has achieved one of the desired objectives by reducing plagiarism, but the ethical dimension has not been tackled: many of our students still do not understand the ethical implications of plagiarism, and the Internet appears as a large repository of information without any implication. A deeper exploration of the ethical dimension of academic work remains necessary, with a focus on rigour, recognition and valuation of intellectual property, teaching students to respect the work of others as a starting point, but not a final reproducible product.

Finally, we acknowledge that the proposed improvement is limited in terms of the sample size and the elements of comparison, but may be the basis for a more comprehensive study that should expand the study population and may include activities from different courses, degrees and teaching modalities (e.g. online vs. face-to-face). In addition, this study is local to a specific university and language, and should be cross-referenced with other international studies.

The world changes and teaching processes should try to change to keep pace, either through new regulations or teaching methods. We believe that we may have shed some light into the thought process that prompts our students to plagiarize with such carelessness, demonstrating that the solution does not only lie on coercive methods, and that there is room for positive approaches.

References

Ashworth, P., Bannister, P., & Thorne, P. (1997). Guilty in whose Eyes? University Students’ Perceptions of Cheating and Plagiarism in Academic Work and Assessment. Studies in Higher Education, 22(2), 187-203. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079712331381034

Atkins, T., & Nelson, G. (2001). Plagiarism and the Internet: Turning the Tables. English Journal, 90(4), 101-104. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/821911

Bretag, T. (2013). Challenges in Addressing Plagiarism in Education. PLoS. Medicine, 10(12), e1001574. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930301677

Chen, Y. & Chou, C. (2014). Why and Who Agree on Copy-and-Paste? Taiwan College Students’ Perceptions of Cyber-Plagiarism. In J. Viteli, & M. Leikomaa (Eds.), Proceedings of EMedia : World Conference on Educational Media and Technology 2014 (pp. 937-943). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). (https://goo.gl/Zo4q5e) (2016-08-03).

Clegg, S., & Flint, A. (2006). More Heat than Light: Plagiarism in its Appearing. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 27(3), 373-387. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01425690600750585

Comas, R., Sureda, J., & Oliver, M. (2011). Prácticas de citación y plagio académico en la elaboración textual del alumnado universitario. Teoría de la Educación: Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información, 12 (1), 359-385. (http://goo.gl/Xl9JMX) (2016-08-03).

Culwin, F., & Lancaster, T. (2001). Plagiarism Issues for Higher Education. VINE, 31(2), 36-41. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03055720010804005

DeVoss, D., & Rosati, A.C. (2002). It wasn’t me, was it? Plagiarism and the Web. Computers and Composition, 19(2), 191-203. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S8755-4615(02)00112-3

Eddy, M. (2013). German Politician Faces Plagiarism Accusations. The New York Times. (http://goo.gl/GTDUju) (2016-08-03).

Ellery, K. (2008). Undergraduate Plagiarism: a Pedagogical Perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 507-516. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930701698918

Eret, E., & Gokmenoglu, T. (2010). Plagiarism in Higher Education: A Case Study with Prospective Academicians. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 3.303-3.307. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.505

Eret, E., & Ok, A. (2014). Internet Plagiarism in Higher Education: Tendencies, Triggering Factors and Reasons among Teacher Candidates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(8), 1.002-1.016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.880776

Gómez, J., Salazar, I., & Vargas, P. (2012). Factors Explaining Student Plagiarism: an Empirical Test in a Spanish University, ICERI2012 Proceedings, 2.724-2.730.

Hart, M., & Friesner, T. (2004). Plagiarism and Poor Academic Practice – A Threat to the Extension of e-learning in Higher Education. Electronic Journal on E-Learning, 2(1), 89-96. (http://goo.gl/zqu78L) (2016-01-08)

Heckler, N., & Forde, D. (2015). The Role of Cultural Values in Plagiarism in Higher Education. Journal of Academic Ethics, 13(1), 61-75. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10805-014-9221-3

Hussein, N., Rusdi, S.D., & Mohamad, S.S. (2016). Academic Dishonesty among Business Students: A Descriptive Study of Plagiarism Behavior. In Y.C. Fook, K.G. Sidhu, S. Narasuman, L.L. Fong, & B.S. Abdul-Rahman (Eds.), 7th International Conference on University Learning and Teaching (InCULT 2014) Post-Proceedings: Educate to Innovate (pp. 639-648). Springer Singapore. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-664-5_50

Kauffman, Y., & Young, M.F. (2015). Digital Plagiarism: An Experimental Study of the Effect of Instructional Goals and Copy-and-Paste Affordance. Computers & Education, 83, 44-56. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.12.016

Moore, R. (2007). Understanding ‘Internet Plagiarism’. Computers and Composition, 24, 3-15. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2006.12.005

Newton, P. (2015). Academic Integrity: a Quantitative Study of Confidence and Understanding in Students at the Start of their Higher Education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1-16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1024199

Perry, B. (2010). Exploring Academic Misconduct: Some Insights into Student Behaviour. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(2), 97-108. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1469787410365657

Six Degres (2008). Los usos de Internet en la educación superior: ‘De la documentación al plagio’. Survey by Six Dregres, Compilatio.net and Sphinx Development. (http://goo.gl/avllYX) (2016-08-03).

Sureda, J., Comas, R., & Oliver, M.F. (2015). Academic Plagiarism among Secondary and High School Students: Differences in Gender and Procrastination. [Plagio académico entre alumnado de Secundaria y Bachillerato: diferencias en cuanto al género y la procrastinación]. Comunicar, 22(44), 103-111. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C44-2015-11

Vallejo, M. (2011). Trabajos escritos: el problema del plagio. Escribir para aprender, tareas para hacer en casa. Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar. (http://goo.gl/lfTRzf) (2016-08-03).

Walker, J. (2010). Measuring Plagiarism: Researching what Students do, not what they Say they do. Studies in Higher Education, 35(1), 41-59. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070902912994

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es comprender mejor la naturaleza del plagio en la Educación Superior. Analizamos una serie de actividades en un curso on-line de nivel universitario, con el objetivo de encontrar qué tareas llevan más naturalmente al plagio. Este análisis concluye que las actividades que tienen una menor tasa de plagio son actividades que fomentan la participación, la originalidad y la creatividad. Posteriormente, reformulamos la tarea que presenta la mayor tasa de plagio, teniendo en cuenta las conclusiones del análisis anterior y tratando de mantener su esfuerzo relativo y el impacto educativo. A continuación, comparamos las actividades del nuevo diseño con las originales para medir si el rediseño conlleva una reducción significativa del plagio. Los resultados son claros y muestran una caída significativa en los porcentajes de plagio. Además, se realizó una validación adicional en la que se analizó la actividad con la segunda tasa de plagio más alta, encontrando que los grupos eran comparables y mostraban actitudes de plagio similares en otros ejercicios que no habían sido rediseñados. Este estudio muestra que es posible reducir la incidencia de plagio mediante el diseño de actividades de tal manera que los estudiantes se sientan motivados para proponer sus propias ideas utilizando la información disponible en Internet como vehículo para sus soluciones en lugar de como soluciones en sí mismas.

1. Introducción

Desafortunadamente, el plagio se ha convertido en un problema común y generalizado a todos los niveles, y es fácil encontrar en los medios de comunicación casos de plagio en niveles educativos superiores. Por ejemplo, en los últimos años hemos asistido a la dimisión de dos ministros alemanes acusados de plagio en sus tesis doctorales (Eddy, 2013). Aunque el problema no es nuevo, la revolución que ha supuesto Internet en el modo de buscar y acceder a la información ha hecho aumentar el plagio en el ámbito educativo. A los estudiantes se les pide realizar y entregar ejercicios, ensayos o soluciones a problemas y toda la información se encuentra tan solo a unos clics de distancia (Atkins & Nelson, 2001; DeVoss & Rosatti, 2002; Moore, 2007). El objetivo de este trabajo es obtener una mejor comprensión de la naturaleza del plagio, especialmente en los casos en los que este no se debe a la complejidad de la tarea.

1.1. El plagio en la educación superior

Internet ha irrumpido en todos los aspectos de nuestra vida diaria, incluyendo las aulas universitarias, y ha abierto nuevas formas de buscar solución a las tareas de clase. Muchos estudiantes buscan la solución más rápida a las tareas, independientemente de la validez de las fuentes o sin respetar el trabajo de los demás, un fenómeno que se ha generalizado en todos los niveles educativos (Sureda, Comas, & Oliver, 2015). En este caso, nuestra atención se centra en la educación superior, donde el aumento del plagio ha sido una preocupación constante en los últimos años (Culwin & Lancaster, 2001; Hart & Friesner, 2004; Clegg & Flint, 2006; Ellery, 2008; Eret & Gokmenoglu, 2010; Bretag, 2013; Heckler & Forde, 2015), estando los profesores cada vez más preocupados por la frecuencia y la aparente falta de conciencia por parte de los estudiantes sobre sus implicaciones morales (Perry, 2010).

Los resultados de una encuesta realizada por las empresas Six Degrés (2008) y Le Sphinx Développement mostraron algunos comportamientos significativos de estudiantes y profesores, identificando Internet como la principal fuente de documentación (90%) y con un 43% de los estudiantes admitiendo que nunca o rara vez habían citado sus fuentes. Estos resultados son consistentes con otro experimento llevado a cabo entre 1.025 estudiantes (Comas, Sureda, & Oliver, 2011), que establece que 7 de cada 10 estudiantes universitarios admiten haber copiado textos o fragmentos de textos para el desarrollo de sus actividades académicas, presentándolas como propias.

Otros estudios realizados en diferentes entornos muestran la frecuencia de estas prácticas poco éticas, pero introducen matices. La Universidad de La Rioja (España) en 2011-12 llevó a cabo un experimento empírico que analizó 104 entregas de un título de nivel universitario en Dirección de Empresas. Los estudiantes tenían que presentar diferentes tareas durante el curso, así como un ensayo final con gran peso en la calificación final. Entre los documentos presentados, 13 de ellos (12,5%) mostraron una tasa de plagio superior al 40%, una cifra mucho mayor de lo que podría considerarse razonable académicamente. Resulta interesante observar que cuanto mayor era el peso de la actividad en la nota final, menor era el porcentaje de plagio, lo que sugiere un vínculo interesante entre la importancia percibida de la tarea y la tendencia a plagiar (Gómez, Vargas, & Salazar, 2012). En cuanto a la actitud de los estudiantes hacia el plagio, un estudio reciente de Newton (2015) señaló que los estudiantes consideraban que «una mala conducta académica debe ser penalizada con modestia», pero luego se volvían más estrictos después de graduarse.

En cuanto a los factores que invitan a los estudiantes a plagiar, incluso antes de la era de Internet, Ashworth, Bannister y Thorne (1997) identificaron cuatro cuestiones fundamentales: 1) la falta de conciencia de los alumnos respecto a si están plagiando o no; 2) la baja probabilidad de ser detectado; 3) la presión derivada del nivel de exigencia y los plazos establecidos para las entregas; y 4) la propia redacción de las actividades proporcionadas por los profesores. Estos factores son aún relevantes: un estudio más reciente de Eret y Ok (2014) observó que la tendencia a plagiar ha aumentado con la llegada de Internet, y señala como principales razones para el plagio las limitaciones de tiempo, las cargas de trabajo excesivas y una alta dificultad de las tareas propuestas. Estos resultados son consistentes, en términos de razones para el plagio, con los hallazgos de Chen y Chou (2014) en un estudio local centrado en estudiantes taiwaneses. Otro estudio reciente de Hussein, Rusdi y Mohamad (2016) encontró que los estudiantes eran totalmente conscientes de lo que era el plagio y de que no es apropiado. Sin embargo, esto no era suficiente para disuadirlos del plagio por las razones anteriormente mencionadas. Un estudio más directo de Kauffman y Young (2015) analizó cómo la facilidad de acceso a herramientas para copiar y pegar y la presentación de las tareas influían en las actitudes hacia el plagio.

En resumen, la mayoría de los estudios coinciden en que el acceso a la información ha llegado a ser tan inmediato que es percibido por algunos como un «conocimiento común» disponible para que todo el mundo lo reproduzca (Walker, 2010). Estos problemas generalizados han dado lugar a una respuesta académica / tecnológica en búsqueda de nuevas formas y herramientas para detectar el plagio, tal como se describe en la siguiente sección.

1.2. Herramientas de detección de plagio

Muchas instituciones tratan el problema del plagio usando diversos métodos para detectar las copias. Estos métodos van desde los más sencillos (por ejemplo la búsqueda inversa en Google, o cualquier otro buscador general) hasta aquellos que usan herramientas más complejas con controles más exhaustivos.

Algunas herramientas automatizan el proceso de revisión inversa. Dos de las herramientas más citadas en esta categoría son Plagiarism Checker (http://goo.gl/kElH) y Article Checker (http://goo.gl/GgYtQ). También en esta categoría se encuentran CopioNIC (https://goo.gl/KQL9Ru), una aplicación web gratuita (requiere registro), que permite subir archivos para hacer la búsqueda y Magister de Compilatio.net (https://goo.gl/FqnPHb) que permite tanto a los estudiantes como a los profesores subir documentos y comprobar sus resultados on-line. Por otro lado, existen también productos más interesantes para los profesores que tienen sus propias bases de datos. Dos ejemplos de estos productos son Viper Plagiarism (http://goo.gl/TrBey) y Turnitin (http://goo.gl/ixhp9). Este último es uno de los recursos más utilizados en el mundo académico, y compara los nuevos trabajos con una gran base de datos de contenidos tanto del ámbito académico como de la web. Esta posición dominante podría aumentar debido a su reciente fusión con Ephorus (https://goo.gl/PifnGN), presente también en múltiples instituciones universitarias.

Estas herramientas compiten con otros sistemas como CrossCheck (http://goo.gl/DFB0vQ), que fue inicialmente creada para artículos académicos, pero que se está convirtiendo en otra herramienta de referencia para la detección del plagio en el contexto educativo.

Este mercado en expansión de herramientas de detección de plagio está en apariencia suficientemente maduro como para que la detección de plagio no sea un desafío. Sin embargo, los casos de plagio siguen siendo habituales, incluso cuando los estudiantes son conscientes de la existencia de estas herramientas. Parte del problema puede estar relacionado con las limitaciones de las herramientas, tal y como identificó Vallejo (2011), entre las que se encuentran el hecho de que los alumnos pueden «engañar» a las herramientas, las limitaciones del lenguaje, o los procesos excesivamente pesados. Pero, sin dejar de lado el poder de estas herramientas, en realidad son solo parte de la solución. Es importante complementar el uso de estas herramientas con cambios en la metodología y con el fomento de buenas prácticas, buscando la honestidad e integridad académica de forma intrínseca.

2. Material y métodos

El objetivo principal de este trabajo es comprender las razones que llevan a los estudiantes a cometer plagio y estudiar si un cambio en el diseño de las actividades que tienen que realizar puede tener un impacto sobre las tasas de plagio. El estudio se organizó en dos fases: 1) Un estudio preliminar para detectar las actividades que presentaban un mayor índice de plagio a lo largo de un curso; 2) Una intervención específica dirigida a reducir las tasas de plagio en aquellas actividades en las que el plagio era más significativo.

La hipótesis de la presente investigación parte del principio que es posible reducir el plagio cambiando la presentación y exposición de la actividad, manteniendo intacta tanto la dificultad como el objetivo educativo.

2.1. Curso objetivo y población estudiantil

Esta investigación ha sido realizada en el contexto de la asignatura «Matemáticas, Complementos de formación», que forma parte del Grado de Maestro en Educación Primaria impartido en la Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR) en la modalidad on-line. La evaluación de esta asignatura se realiza siguiendo los criterios marcados por el Plan Bolonia, que busca incrementar la importancia de la evaluación continua frente al examen final. La asignatura tiene un modelo mixto de evaluación en el que la calificación final se compone de dos partes: un 60% corresponde al examen final presencial; y un 40% se obtiene de las calificaciones obtenidas en un conjunto de actividades formativas que el estudiante realiza a lo largo del cuatrimestre. Las actividades formativas propuestas suman un total de 6 puntos, por lo que los estudiantes pueden seleccionar actividades concretas y no están obligados a realizar todas las propuestas.

En las dos etapas de la investigación intervinieron dos grupos de estudiantes de la misma asignatura:

• Grupo A: 65 estudiantes matriculados en el año académico 2011-12.

• Grupo B: 94 estudiantes matriculados en el año académico 2012-13.

Los estudiantes del Grupo A fueron la base del estudio preliminar para detectar la incidencia del plagio en las diferentes actividades propuestas durante el curso. Después de diseñar la intervención específica, estos estudiantes fueron considerados el grupo de control, siendo los estudiantes del Grupo B el grupo experimental.

2.2. Estudio previo: identificación y comprensión del plagio en un curso on-line

Como se ha indicado anteriormente, el primer paso de la investigación consistió en analizar el porcentaje de plagio en las actividades de evaluación continua propuestas a los estudiantes a lo largo del año académico. Los estudiantes trabajan en un campus virtual on-line, en el que tienen disponibles las actividades y las puntuaciones de las mismas. Estas son las actividades propuestas a los estudiantes para obtener los cuatro puntos necesarios para la evaluación continua:

• Test de autoevaluación: 14 test de autoevaluación con preguntas de selección simple para cada uno de los temas de la asignatura, con un valor de 0,05 puntos por prueba.

• Asistencia a sesiones presenciales virtuales: La asistencia a dos sesiones presenciales virtuales se valora con 0,15 puntos cada una.

• Participación en los foros de discusión: Los foros buscan fomentar la participación y discusión entre los estudiantes. Los estudiantes pueden conseguir un máximo de 0,5 puntos, y la calificación tiene en cuenta el número de intervenciones, y la calidad y relevancia de las mismas.

• Actividades abiertas: Estas tareas incluyen actividades como la creación de un glosario de términos matemáticos, un trabajo de geometría, análisis estadísticos, etc. Hay diferentes tareas con puntuaciones entre 0,5 y 1 punto cada una.

• Lecturas y reflexiones personales: Las lecturas se centran en la revisión de artículos, noticias, etc. y la posterior reflexión personal sobre ellas. El estudiante puede obtener un máximo de 1 punto por cada una de ellas.

Para el desarrollo del estudio inicial hemos analizado el comportamiento de los estudiantes del Grupo A (2011-12) para entender los porcentajes de participación y las tendencias de plagio.

2.2.1. Análisis de la participación de los estudiantes

Como se ha comentado en el punto 2.1, los estudiantes no tienen la obligación de entregar todas las actividades. Cada estudiante puede elegir centrarse en unas actividades formativas e ignorar otras. Con el fin de centrar el objetivo del estudio en actividades concretas, comenzamos por analizar la tasa de participación en las 10 actividades propuestas. La tabla 1 presenta un desglose de las tasas de entrega de cada actividad de la asignatura. Aunque el estudio preliminar se centró en el Grupo A (2011-12), se incluyen también las tasas del Grupo B para su comparación.

Las actividades que presentan un mayor índice de participación son los test y la asistencia a las sesiones presenciales virtuales. La sencillez de estas actividades y la flexibilidad para entregarlas a lo largo de todo el cuatrimestre pueden ser dos de las razones que hagan que el porcentaje de entrega sea tan elevado. Las características de estas actividades hacen que no se pueda cometer plagio en ellas; sin embargo son las que más entregan los alumnos.

Por otra parte, los trabajos y lecturas presentan resultados variados, con tasas de participación que van disminuyendo a medida que avanza el curso y aumenta la dificultad. Las actividades 2, 3 y 9 presentan unos índices muy bajos de participación y esto puede deberse, principalmente, a que ambas actividades implican un alto trabajo de búsqueda de información, lo que supone una inversión de tiempo en la realización de la tarea superior al resto.

2.2.2. Análisis del plagio

Para este punto, hemos ignorado las actividades 1 y 2, ya que no implican ningún proceso de elaboración propio del estudiante. En total los estudiantes enviaron más de 350 actividades a lo largo del cuso 2011-12. Dadas las limitaciones de tiempo a lo largo del curso, hemos seleccionado una muestra aleatoria para analizar las tasas de plagio (un máximo de 23 entregas por tarea). La selección se realizó de forma aleatoria para cada tarea, teniendo en cuenta que los estudiantes que optan por cada entrega son diferentes. En aquellas actividades donde el número de tareas entregadas fue menor a 23, analizamos todas las actividades entregadas. Todas estas actividades fueron analizadas utilizando la herramienta anti-plagio Turnitin. Los resultados se presentan a continuación agrupados por tipo de actividad.

• Foros: Entre las actividades entregadas en los 2 foros un 36,36% presentan plagio. Aunque el porcentaje no es muy elevado, el tipo de plagio es muy grave, ya que es una actividad en la que se pide explícitamente a los estudiantes que incluyan sus opiniones personales.

• Actividades abiertas: La actividad 9 sobre la creación de un proyecto estadístico solo fue entregada por tres estudiantes. Es de destacar, sin embargo, que dos de ellas eran completamente originales, pero la tercera presentaba una tasa de plagio de un 31%. Las actividades 3, 5 y 8 tienen características especiales, ya que buscan definir contenidos matemáticos y para ello es normal recurrir a definiciones clásicas, comúnmente aceptadas y que aparecen en numerosas páginas de Internet.

• Lecturas y reflexiones personales: En la actividad 6 no se detecta ningún caso de plagio. Es una actividad que busca analizar los datos de un periódico actual, localizando los diferentes tipos de números y de conceptos matemáticos que aparecen en él. Los estudiantes eligen todo tipo de periódicos, tanto de información general como temáticos, y la presentación de esta actividad también es variada entregando los datos tanto en tablas esquemáticas como en informes más desarrollados.

Por su parte, la actividad 5 presenta resultados mucho peores. Todas las entregas (100%) presentan coincidencias con fuentes no citadas o citadas incorrectamente (tabla 2). Siete de estas actividades (30,4%) incluyen porcentajes de plagio por encima del 80%, llegando en el peor de los casos al 96%. Solo cinco de los trabajos analizados devuelven porcentajes por debajo del 25%.

2.2.3. Resultados preliminares

Los datos analizados muestran que la actividad 5 es la que presenta una mayor tasa de plagio, así como el mayor índice de participación si excluimos los test y las clases on-line. La tasa de plagio en esta actividad es tan alta que no puede atribuirse exclusivamente a los estudiantes, ya que no se han detectado índices tan altos en otras actividades. Cabe destacar que esta actividad se centra en un tema muy específico, fácilmente localizable en Internet, apenas relacionado con noticias y con muy pocas aplicaciones directas en el aula.

Después de un cuidadoso análisis, y sin excusar el comportamiento poco ético de algunos estudiantes, tenemos que considerar que el diseño instruccional de la actividad no es correcto, ya que fomenta ese comportamiento en una amplia representación de estudiantes que sí han entregado trabajos originales en otras actividades. Por otro lado, no parece que el esfuerzo que requiere la actividad sea un factor determinante para el incremento del plagio, ya que la actividad del análisis de los elementos numéricos del periódico también tiene una alta carga de trabajo y sin embargo la tasa de plagio es menor.

Habiendo examinado las diferentes actividades propuestas y sus características, se puede ver que aquellas que tienen una menor tasa de plagio son las que implican una participación más personal de los estudiantes, con opiniones y propuestas, así como aquellas cuyos contenidos están vinculados a elementos presentes en su vida cotidiana y en su entorno más cercano. En resumen, en actividades que promueven la participación, la originalidad y la creatividad. A partir de estas conclusiones preliminares, tratamos de comprobar si los cambios en el diseño (pero no en el significado profundo) de una actividad pueden tener un impacto en las tasas de plagio.

2.3. Diseño de la intervención

En esta sección se presenta el diseño del experimento para reducir el plagio: después de identificar la actividad que había presentado la tasa más alta de plagio, esta actividad fue rediseñada y presentada a un nuevo grupo de estudiantes (Grupo B). Estos estudiantes (n=94) se matricularon en el curso 2012-13, en la misma asignatura, con la misma agenda, programación, secuenciación y evaluación.

2.3.1. Rediseño de la actividad 5

Esta actividad fue seleccionada para el análisis de la hipótesis. El diseño original de la actividad se planteaba como una pregunta de respuesta abierta con el objetivo implícito de que los estudiantes presentaran una respuesta con los datos correspondientes de tal manera que se pudieran usar en un aula de Educación Primaria. La definición de la actividad era la siguiente:

• Lectura: Números de primera: En la lectura recomendada para este tema, el Diablo de los Números presenta a Robert unos números especiales: esos que él llama los números de primera. En el mundo real estos números se llaman números primos y como nuestro protagonista dice «Los matemáticos llevan mil años rompiéndose la cabeza con ellos. Son unos números maravillosos. Por ejemplo el once, el trece o el diecisiete...». Investiga sobre el significado de los números primos y escribe un breve ensayo en el que recojas las ideas clave sobre estos números (definición, evolución histórica, propiedades, curiosidades…).

Durante el curso 2012-13, el título y la descripción de la actividad fueron modificadas, siguiendo unas pautas que trataron de evitar el plagio entre los estudiantes, de acuerdo a las conclusiones extraídas en el estudio preliminar. Con este propósito, la actividad se presentó a los estudiantes de la siguiente manera:

• Lectura: Explicando qué son los números de primera: En la lectura recomendada para este capítulo el Diablo de los Números presenta a Robert unos números especiales: esos que él llama los números de primera. En el mundo real estos números se llaman números primos y como nuestro protagonista dice «Los matemáticos llevan mil años rompiéndose la cabeza con ellos. Son unos números maravillosos. Por ejemplo el once, el trece o el diecisiete...». Investiga sobre los números primos y, después, te proponemos realizar la siguiente actividad: Imagínate delante de una clase de niños entre 9 y 10 años, a los que tuvieras que explicar brevemente qué son los números primos. Redacta en media hoja (no más de 30 líneas), cómo se lo explicarías. Si quieres, en la mitad inferior de la hoja, puedes añadir una imagen o esquema. Intenta hacerlo ameno, original, didáctico, etc., ¡ten en cuenta que se lo estás explicando a niños!

• Objetivos de la actividad: Ser conscientes de la relevancia que tienen los números primos para las Matemáticas. Asumir el rol de maestro preparando (esquemáticamente) una clase a estudiantes de Primaria. Realizar una actividad motivadora de cara a tu futuro profesional como maestro.

• Criterios de evaluación: Los conceptos expuestos y explicados sobre los números primos y sus propiedades deben ser correctos; se valorará el grado de originalidad y creatividad en la elaboración de la clase; redacción y ortografía adecuadas.

El nuevo diseño de la actividad da pautas concretas incluyendo la necesidad de desarrollar la actividad para un entorno real y cercano (un aula de primaria). La actividad se presenta como una pequeña investigación que propone la búsqueda de datos, pero enfocando la entrega como una propuesta personal, que busca la creatividad del alumno, y no una mera enumeración de los datos encontrados. Los criterios de evaluación hablan explícitamente sobre cómo usar los materiales aportados y de cómo se tendrá en cuenta el rigor y la claridad de los contenidos expuestos. Con el nuevo diseño de la actividad, los estudiantes son conscientes de que se valorará la creatividad, pero también son conscientes de la importancia de los datos proporcionados. Lo más importante, la rúbrica de evaluación, el tiempo para realizar la actividad y la fecha de entrega se mantuvieron igual a la actividad original; solo cambió la descripción de la actividad.

Figura 1. Tasas de plagio en el grupo de control.

2.3.2. Diseño experimental

El rediseño de la actividad se presentó a los estudiantes en el siguiente año académico para su comparación. Los estudiantes del curso académico 2011-12 (Grupo A) serán considerados el grupo de control, mientras que los estudiantes del curso académico 2012-13 (Grupo B) serán considerados el grupo experimental. Una vez finalizado el curso se tomaron dos medidas importantes:

• Medidas #1: Una comparación en profundidad de las tasas de plagio en la actividad 5, con el fin de comprender si el nuevo diseño da como resultado tasas de plagio más bajas. Las tasas de plagio de cada grupo serán analizadas y comparadas usando la prueba T para comprobar si las diferencias en los porcentajes de plagio son estadísticamente significativas.

• Medidas #2: Una comparación entre las tasas de plagio de los dos grupos en otra actividad, para comprobar si los dos grupos eran realmente comparables en sus prácticas de plagio en el día a día y en su rendimiento general. La segunda medida es importante para descartar diferencias significativas entre los grupos (por ejemplo, el grupo experimental podría estar compuesto por estudiantes con unos principios éticos más fuertes en relación al plagio).

Figura 2. Tasas de plagio en el grupo experimental.

3. Resultados

Aunque el Grupo A era más numeroso que el B, sus tasas de entrega relativas eran similares, como se observa en la tabla 1. Las dos excepciones más notables se produjeron en las actividades 3 y 9. Lo más relevante para nuestro estudio es que la media de entregas de la actividad 5 está por encima del 75% en ambos cursos académicos. A pesar del cambio en el diseño de la actividad no se observaron cambios significativos en la tasa de participación, manteniendo un alto porcentaje de entregas.

3.1. Porcentaje de plagio (Medidas #1)

El primer paso fue realizar un análisis en profundidad de todas las entregas de la actividad 5 en ambos cursos. En total hubo 50 entregas en el grupo de control (Grupo A) y 78 entregas en el grupo experimental (Grupo B), teniendo en cuenta que los estudiantes no están obligados a entregar todas las tareas. Las figuras 1 y 2 indican las tasas de plagio encontradas en cada entrega para ambos grupos. Los resultados son destacables, con muy pocos casos de plagio entre los estudiantes del grupo experimental, y con solo dos casos aislados que presentan tasas por encima del 30%.

Como resultado (tabla 3), la media de plagio en el grupo experimental (M=3,87, SD=10,26) es mucho menor que la del grupo de control (M=47,66, SD=29,96). Esta diferencia es estadísticamente significativa, t (56.4=9.97, p<.000, d= 4.39). El test de Levene para la igualdad de varianzas no se cumplía, por lo que la prueba-t no asume una varianza homogénea.

3.2. Comparación de rendimiento (Medidas #2)

Si bien el análisis de tasas de plagio muestra una mejora significativa, es importante comprobar si ambos grupos son realmente comparables, tratando de reducir posibles factores potenciales de confusión. Esto es especialmente importante ya que los instructores no tienen acceso a los datos demográficos de los estudiantes.

En la tabla 1 se puede observar que las tasas de entrega estaban razonablemente equilibradas. Además, también hemos estudiado el desempeño en otra actividad para asegurar que los dos grupos eran comparables. Hemos analizado los resultados de la actividad con la segunda mayor tasa de coincidencias, la actividad 7, en la que los estudiantes deben elegir fotografías y analizar los elementos matemáticos que aparecen en ellas. Esta actividad tuvo un alto grado de coincidencias, de múltiples fuentes, normalmente sin referencias, de las que los alumnos extrajeron las definiciones que acompañaban a las fotografías.

Como se observa en la tabla 4, en este caso el grupo experimental muestra unos datos ligeramente mejores (M=22,09, SD=6,24) que el grupo de control (M=28,82, SD=6,01), con solo una diferencia de 6,73% que se identificó como no significativa durante el análisis estadístico.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Debido al creciente interés que el plagio está generando en contextos de Educación Superior, este trabajo se ha centrado en comprender por qué y cómo plagian los estudiantes, con el objetivo de explorar enfoques constructivos para reducir el plagio.

Comenzamos el estudio con un análisis de los patrones de plagio en una asignatura de un grado on-line, observando y analizando cómo las tasas de plagio eran diferentes en función del tipo de tarea. En este estudio preliminar, se identificaron las tareas que eran más propensas al plagio y en lugar de aumentar la severidad de nuestros métodos más coactivos, tratamos de mejorar esta situación promoviendo una motivación interna hacia la creatividad. En nuestro experimento principal se cambiaron las instrucciones de la actividad, pero no el propósito ni la rúbrica de evaluación de la misma.

Los resultados muestran unas diferencias muy significativas entre el grupo experimental y el de control. Esto indica que el modo en el que el ejercicio se redacta tiene un fuerte impacto en la actitud de los estudiantes. Es importante indicar que los estudiantes no recibieron ningún aviso especial advirtiendo sobre el plagio diferente a los habituales que todos los grupos reciben al comienzo del curso. Esto contrasta con las percepciones existentes sobre por qué los estudiantes harían trampas: pereza, dificultad de las tareas, falta de comprensión sobre las implicaciones morales, etc. Con esta prueba hemos obtenido una respuesta positiva de nuestros estudiantes, sustituyendo el enfoque habitual (amenazas de consecuencias si se detecta el engaño) por una propuesta que les permite ser creativos y originales.

Por lo tanto, este estudio muestra que es posible reducir la incidencia de plagio diseñando actividades en las que se fomenta que los estudiantes propongan sus propias ideas, y en las que utilicen Internet como vehículo para localizar información ya existente que les ayude a encontrar soluciones, pero no la tarea principal.

Cabe señalar, sin embargo, que este experimento ha conseguido uno de los objetivos buscados reduciendo el plagio, pero la dimensión ética no se ha abordado: muchos de nuestros estudiantes siguen sin comprender las implicaciones éticas del plagio, y consideran Internet como un gran repositorio de información del que se puede disponer sin ninguna otra implicación. Sigue siendo necesaria una exploración más profunda de la dimensión ética del trabajo académico, con especial atención en el rigor, el reconocimiento y la valoración de la propiedad intelectual, enseñando a los alumnos a respetar el trabajo de los demás como punto de partida, pero no como un producto final y reproducible.

Por último, reconocemos que la contribución de la investigación presenta limitaciones en cuanto al tamaño de la muestra y a los elementos comparados, pero consideramos que puede ser la base para un trabajo más exhaustivo que debe ampliar la población de estudio y debe incluir actividades de diferentes asignaturas, estudios y modalidades de formación (por ejemplo, on-line frente a presencial). Además, este análisis está limitado a una universidad e idioma concretos, y debería completarse con referencias cruzadas con otros trabajos internacionales.

El mundo cambia y los procesos de enseñanza deben intentar seguir el ritmo, ya sea a través de nuevos reglamentos o de nuevos métodos de enseñanza. Creemos que este estudio puede arrojar algo de luz en el proceso que lleva a nuestros alumnos a plagiar con tanto descuido. La solución no solo radica en métodos coercitivos: hay espacio para enfoques positivos.

Referencias

Ashworth, P., Bannister, P., & Thorne, P. (1997). Guilty in whose Eyes? University Students’ Perceptions of Cheating and Plagiarism in Academic Work and Assessment. Studies in Higher Education, 22(2), 187-203. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079712331381034

Atkins, T., & Nelson, G. (2001). Plagiarism and the Internet: Turning the Tables. English Journal, 90(4), 101-104. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/821911

Bretag, T. (2013). Challenges in Addressing Plagiarism in Education. PLoS. Medicine, 10(12), e1001574. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930301677

Chen, Y. & Chou, C. (2014). Why and Who Agree on Copy-and-Paste? Taiwan College Students’ Perceptions of Cyber-Plagiarism. In J. Viteli, & M. Leikomaa (Eds.), Proceedings of EMedia : World Conference on Educational Media and Technology 2014 (pp. 937-943). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). (https://goo.gl/Zo4q5e) (2016-08-03).

Clegg, S., & Flint, A. (2006). More Heat than Light: Plagiarism in its Appearing. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 27(3), 373-387. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01425690600750585

Comas, R., Sureda, J., & Oliver, M. (2011). Prácticas de citación y plagio académico en la elaboración textual del alumnado universitario. Teoría de la Educación: Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información, 12 (1), 359-385. (http://goo.gl/Xl9JMX) (2016-08-03).

Culwin, F., & Lancaster, T. (2001). Plagiarism Issues for Higher Education. VINE, 31(2), 36-41. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03055720010804005

DeVoss, D., & Rosati, A.C. (2002). It wasn’t me, was it? Plagiarism and the Web. Computers and Composition, 19(2), 191-203. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S8755-4615(02)00112-3

Eddy, M. (2013). German Politician Faces Plagiarism Accusations. The New York Times. (http://goo.gl/GTDUju) (2016-08-03).

Ellery, K. (2008). Undergraduate Plagiarism: a Pedagogical Perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 507-516. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930701698918

Eret, E., & Gokmenoglu, T. (2010). Plagiarism in Higher Education: A Case Study with Prospective Academicians. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 3.303-3.307. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.505

Eret, E., & Ok, A. (2014). Internet Plagiarism in Higher Education: Tendencies, Triggering Factors and Reasons among Teacher Candidates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(8), 1.002-1.016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.880776

Gómez, J., Salazar, I., & Vargas, P. (2012). Factors Explaining Student Plagiarism: an Empirical Test in a Spanish University, ICERI2012 Proceedings, 2.724-2.730.

Hart, M., & Friesner, T. (2004). Plagiarism and Poor Academic Practice – A Threat to the Extension of e-learning in Higher Education. Electronic Journal on E-Learning, 2(1), 89-96. (http://goo.gl/zqu78L) (2016-01-08)

Heckler, N., & Forde, D. (2015). The Role of Cultural Values in Plagiarism in Higher Education. Journal of Academic Ethics, 13(1), 61-75. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10805-014-9221-3

Hussein, N., Rusdi, S.D., & Mohamad, S.S. (2016). Academic Dishonesty among Business Students: A Descriptive Study of Plagiarism Behavior. In Y.C. Fook, K.G. Sidhu, S. Narasuman, L.L. Fong, & B.S. Abdul-Rahman (Eds.), 7th International Conference on University Learning and Teaching (InCULT 2014) Post-Proceedings: Educate to Innovate (pp. 639-648). Springer Singapore. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-664-5_50

Kauffman, Y., & Young, M.F. (2015). Digital Plagiarism: An Experimental Study of the Effect of Instructional Goals and Copy-and-Paste Affordance. Computers & Education, 83, 44-56. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.12.016

Moore, R. (2007). Understanding ‘Internet Plagiarism’. Computers and Composition, 24, 3-15. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2006.12.005

Newton, P. (2015). Academic Integrity: a Quantitative Study of Confidence and Understanding in Students at the Start of their Higher Education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1-16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1024199

Perry, B. (2010). Exploring Academic Misconduct: Some Insights into Student Behaviour. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(2), 97-108. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1469787410365657

Six Degres (2008). Los usos de Internet en la educación superior: ‘De la documentación al plagio’. Survey by Six Dregres, Compilatio.net and Sphinx Development. (http://goo.gl/avllYX) (2016-08-03).

Sureda, J., Comas, R., & Oliver, M.F. (2015). Academic Plagiarism among Secondary and High School Students: Differences in Gender and Procrastination. [Plagio académico entre alumnado de Secundaria y Bachillerato: diferencias en cuanto al género y la procrastinación]. Comunicar, 22(44), 103-111. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C44-2015-11

Vallejo, M. (2011). Trabajos escritos: el problema del plagio. Escribir para aprender, tareas para hacer en casa. Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar. (http://goo.gl/lfTRzf) (2016-08-03).

Walker, J. (2010). Measuring Plagiarism: Researching what Students do, not what they Say they do. Studies in Higher Education, 35(1), 41-59. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070902912994

Document information

Published on 30/06/16

Accepted on 30/06/16

Submitted on 30/06/16

Volume 24, Issue 2, 2016

DOI: 10.3916/C48-2016-04

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?