(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== The c...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 289128310 to Perez-Manzano Almela-Baeza 2018a) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 12:43, 27 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The current growth in gamification-based applications, and especially in what is known as Digital Game-based Learning (DGBL), is providing new opportunities with considerable educational potential. In the present study, we report on the results of the progress of a project for developing a setting for a gamified website carried out ad hoc, complemented by transmedia resources and aimed at scientific promotion and the promotion of technological and scientific careers (S&T) in adolescents, who are at a stage in life when career preferences are established. At present, the decrease in S& careers is one of the greatest problems for the society of technological development that we live in, where the number of professionals working in key areas for economic development and progress is declining. After completing a pre and post project participation survey, the results suggest a high level of efficiency achieved by projects of this type due to their online experimentation design, the knowledge of real cases of research activity, and the communication of positive scientific values and attitudes appropriate for the target population. The participants significantly increased their interest in the subject area, scientific professions, and research activity and their social benefits demonstrating the acquisition of positive attitudes towards scientific knowledge and skills.

1. Introduction and current issues

The gradual introduction of information and communications technology (ICT) is the greatest challenge faced in education. As with any large-scale methodological change, it is not without controversy and is affected by a lack of resources, misinformation, and all kinds of resistance. Local education authorities, generally limited by scarce resources and a lack of creativity, advocate the convenient stance of “do it yourself”, convincing teaching staff that it is part of their duty to innovate, learn new ICT tools, and introduce them into the classroom or school. It is often forgotten that the preparation and use of ICT require teachers to dedicate much more time compared with conventional teaching methodologies (Ferro-Soto, Martínez-Senra, & Otero-Neira, 2009): “the use of ICT can take away time that the teacher needs to carry out the teacher’s other official tasks”. Nevertheless, it is without any doubt that ICT offers enormous potential in the field of education, creating digital settings, collaborative learning, social mediation and encouraging cross-curricular learning, working on pro-social values and personal attitudes, leading to a less compartmentalised vision of curricular content. Considering ICT as educational tools involves understanding that they provide better channels of educational communication (Coll, Mauri-Majós, & Onrubia-Goñi, 2008). In fact, García-Valcárcel, Basilotta & López-Salamanca (2014) propose “the essential transformation of teaching practice, fostering the development of collaborative projects where ICT becomes a channel of communication providing the information necessary to guarantee learning scenarios which are open, interactive, rich in stimuli and sources of information, and at the same time motivating for the students, focussed on the development of competences”.

Gamification is possibly the methodological tool that has received the most attention, and its introduction in education has been considered particularly relevant (Dicheva, Dichev, Agre, & Angelova, 2015; Wiggins, 2016). In recent years we have witnessed an explosion in the use of this term in specialised journals which present gamification as the new key methodology in education, in school settings and especially, in businesses (Prosperti, Sabarots, & Villa, 2016).

1.1. Elements of game-based learning

Gamification has traditionally been defined as the application of game-related elements in activities that are not games and in other contexts including, of course, education. Its main objective is to improve the intrinsic motivation of the participants. Several authors have focussed on different aspects of gamification. For Huotari and Hamari (2012) an important aspect is that gamification processes should evoke the same psychological experiences as games. Alternatively, Deterding, Dixon, Khaled, and Nacke (2011) have noted the importance of including the same features used in games in the gamification process, regardless of the outcome.

For Perrotta, Featherstone, Aston, and Houghton (2013) so-called Digital Game-Based Learning (DGBL) is developed according to essential principles and mechanisms that express its effectiveness. Perrotta indicates five such principles:

• Intrinsic motivation. Much more powerful than extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation comes from the willingness of the player to participate: the game invites and persuades people to participate. According to Pink (2011), intrinsic motivation is related to three elements that induce it, namely autonomy, competence, and purpose.

• Learning through intensive enjoyment. For one group of authors, led by Csikszentmihalyi (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2009), gaming leads the participants into a flow (Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow Theory), considered as a state of consciousness in which the individual has control over his or her actions while being completely absorbed in the task they are carrying out. Csikszentmihalyi points to eight components that enable flow: that the task is doable, involves concentration, clear objectives, feedback, effortless involvement, control over the actions carried out, the disappearance of one’s consciousness and the loss of sense of time.

• Authenticity. Concern about the real nature of learning compared to more artificial decontextualised ways of traditional teaching. Priority is given to contextual abilities rather than abstract notions of formal learning. Learning processes based on specific practices.

• Autonomy. Playing games encourages independent exploration, bringing together personal interests and preferences, especially in one’s surrounding ecosystem such as in technical and artistic skills (writing, drawing, music) while at the same time encouraging interest in gaining more information about other subjects, such as science or history.

• Experiential learning. Gaming makes it possible to handle situations in which “learning by doing” is a tangible, programmable and manageable option.

According to the literature about this subject, we can identify eight essential elements in the design of games that are usually applied in educational contexts (in DGBL):

• Points. These are a quantitative evaluation of the advances achieved by the player and are usually used as an immediate reward for his or her effort and as a proactive element in the evolution of the player in the game.

• Levels. Levels have normally been used to show the progression in the development of the game. They have been considered as synonyms of the grade of difficulty. The increase in level serves a purpose as a common reward in games, used when tasks or missions have been completed. It is very important to adjust the grade of difficulty for the transition between levels to prevent participants from dropping out or becoming demotivated (All, Nunez Castellar, & Van-Looy, 2014).

• Insignias and badges. These are considered as a visible sign of achievement obtained and aim to maintain the player’s motivation at an adequate level for the following tasks (Gros & Bernat, 2008). Insignias are particularly effective to focus the player’s interest in resolving future challenges or objectives (Chorney, 2012; Santos, Almeida, Pedro, Aresta, & Koch-Grunberg, 2013).

• Classification tables. These improve participant motivation, incentivising their performance in the game and is a way of improving positions. They show the participants’ best scores and are regularly updated. According to O’Donovan, Gain, and Marais (2013), they increase the motivation of participants in educational gamification projects.

• Prizes and rewards. The use of prizes and rewards in the game has been confirmed as a powerful motivator for participants (Brewer & al., 2013) and consequently, their timing in the game and the number of rewards obtained are of special relevance to players’ motivation (Raymer, 2011). The rewards calendar should be adjusted in line with the educational content, the difficulty of the tasks and game levels, preventing possible areas of demotivation and tiredness (Gibson, Ostashewski, Flintoff, Grant, & Knight, 2013).

• Progress bar. This shows the stage of development of the game, the level the player is on, how much he or she has advanced, and how much is left.

• Plot. The story behind the game which gives it meaning. Kapp (2012) suggests that a good plot helps participants to achieve an ever-increasing level of interest, keeping their attention throughout the game, increasing the chances of reaching the end and reducing “dropouts”. The plot also provides a context that is very useful for learning, problem-solving, simulation and the like, making it possible to illustrate and practice the applicability of the concepts.

• Feedback. The information about the player’s activity is given back to him. Its effectiveness will depend on its frequency, intensity, and immediacy (Raymer, 2011; Kapp, 2012; Berkling & Thomas, 2013). Higher frequency and immediacy are related to better results in the game-based learning process. Similarly, feedback is an important indicator of efficiency and immersion in the dynamics of the game (Domínguez & al., 2013).

Once the essential elements of a DGBL product have been configured, it is necessary to check how to strengthen its effects, and in particular, to identify the ideal area for its application (Foncubierta & Rodriguez, 2014).

1.2. The transmedia component

The narrative term transmedia was introduced by Henry Jenkins in 2003, in an article published in “Technology Review”, in which he suggested that “we have entered a new era of the convergence of means which makes it inevitable for contents to flow through different channels”. According to Jenkins transmedia narratives are “stories told through a combination of means”. For Scolari (2013), transmedia storytelling is “a particular narrative form that expands through different meaning systems (verbal, iconic, audiovisual, interactive, etc.)”.

Following his article, Henry Jenkins defined the main principles of transmedia storytelling:

• Expansion vs. depth: Viral expansion through social networks vs. penetration in audiences until they become unconditional fans.

• Continuity vs. multiplicity. Continuity of expression of languages, means, and platforms vs. multiplicity of the creation of experiences starting from the initial plot.

• Immersion vs. extraction. Immersion in the proposed plot vs. extraction of the elements of the story to fit them into the real world.

• World building. Elaboration of characteristics that enrich and make the story realistic, such as details about the characters, the setting, etc.

• Seriality. Organization of the pieces and elements of the main story in a sequence that involves different kinds of media.

• Subjectivity. A mixture of multiple points of view regarding participating characters and plots of the core story.

• Performance. The consumers of the story can promote the main story even converting themselves into creators of similar or complementary contents (pro-consumers, according to Jenkins).

The combination of principles of gamification and transmedia storytelling offers an educational universe with endless potential that fits in and corresponds to the profile of the user that we are dealing with in an educational setting: a multiplatform and an immersive user who can handle multiple tasks at great speed. The user prefers to personalise and manage his or her experiences, making them his or her own, actively participating in, and creating them. The passive teacher became history a long time ago.

1.3. Scientific promotion, attitudes, and pro-science careers

Public attitudes to science not only have an effect on performance in science subjects at school. They can also have an influence on the way society thinks and acts, its social image (and, consequently, the socioeconomic support for scientific research and programs), or the number of researchers or professionals in this field of knowledge (Pérez-Manzano, 2013). Together with this, the persistent decrease in interest in S&T careers is especially relevant (which has been confirmed in a report by the European Commission in 2004) and contrasts with the increase in the demand for S&T professionals.

The relationship between attitudes towards science and S&T careers is clear, and several findings have emerged as a consequence of the high level of scientific production generated about this matter:

• In the ROSE project (Schreiner & Sjøberg, 2004) it has been shown that there are “certain trends or regularities”. For example, there is an inverse relationship between the stage of development of a country and the positive attitudes towards science in young secondary school students (Sjøberg, 2000); Schreiner & Sjøberg, 2005). The decline in pro-science attitudes firstly has consequences for the selection or rejection of subjects and scientific contents, and secondly, it has an effect on the number of professional careers chosen and even generates fixed personal attitudes that are either pro or anti-science.

• Career decision-making becomes stronger among those aged between 14-16 years, that is, those in the 3rd and 4th year of Compulsory Secondary Education (CSE) in Spain.

• The variable of gender is very relevant. Stereotypes, clichés, and social traditions arise when certain professions are related to this variable (Murphy & Beggs, 2003; Vázquez-Alonso & Manassero-Mas, 2009).

• An important component in the career decision-making of girls is the social benefit of the chosen profession as well as the contact with others as a result of carrying out this profession (De-Pro & Pérez, 2014).

2. Material and methods

In light of the aforementioned framework, we considered the need to carry out a project which would facilitate the promotion of scientific activity through a gamification development with transmedia support which could provide an immersive and participative experience.

We proposed the promotion of scientific-technological careers as our general objective by focussing on three components, usually identified in research into the topic as being essential for configuring a clear scientific and technological career:

• The career-decision motivations of active scientists.

• Interest in the real daily work of a researcher.

• The social benefit of scientific activity.

These would be reinforced by two complementary cross-curricular objectives: the management of scientific methodology and the knowledge of unique scientific and technical infrastructure (ICTS) linked to the Region of Murcia (the Hespérides Research Vessel and, therefore, the Antarctic bases) as well as the research carried out from them and their consequent social repercussions. The ICTS are front-line scientific installations at a national and international level that, by themselves, take up most of Spain’s scientific budget and that, in several previous studies (Pérez-Manzano, 2013; De-Pro & Pérez, 2014) appear to be completely unknown to the general public and students of CSE in particular.

We assigned the name of “Antarctic Project” to this proposal. Once it had been designed and presented, its development was accepted by the Telefónica Foundation with the participation of the Local Education Authority of the Region of Murcia (through the Seneca Foundation, the Regional Science and Technology Agency) with the collaboration of the Spanish Polar Committee, the Spanish Army, and the Navy. An exclusive application of the project was offered to secondary schools in the Region de Murcia.

2.1. Methodology

The Antarctic Project consisted of a diverse set of tailor-made materials designed around and supporting a story that is able to attract the target population. It included the following components:

a) Storyline. Given that the whole development of the materials revolves around a storyline, its construction was very important, and the number of transmedia materials produced was determined by it. As the common thread, it was decided to narrate a situation in which different acts of sabotage had been carried out on the Hespérides vessel and the Gabriel de Castilla station to destroy scientific installations or active research development. The idea is passed on that there is a saboteur interested in eliminating the research activity in Antarctica. As the plot develops, the participants can appreciate the social relevance of the research carried out there as well as the fairly unethical activity on the Antarctic continent (indiscriminate tourist use or environmental deterioration). Careful consideration was given to the timeline of the plot to coordinate the contents, level of difficulty, news, communications, and other features.

A certain amount of responsibility was required in developing the plot which is a key aspect of a project of this nature to guarantee the level of immersion in the story used, reinforcing participation and reducing dropouts during the development of the project, and maintaining the interest and motivation of the participants over the three months that the Project lasted.

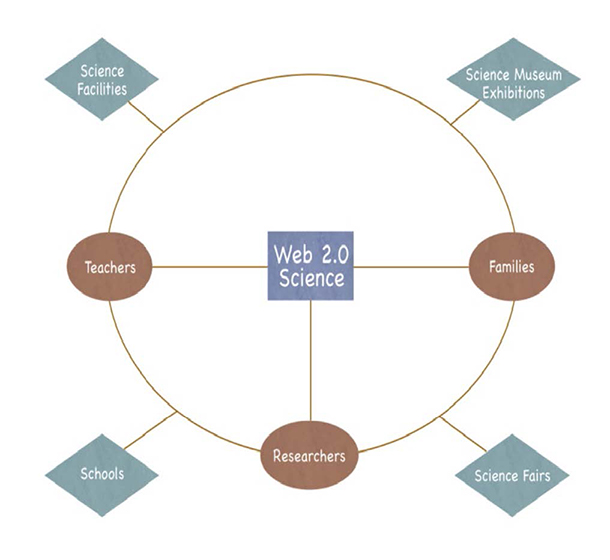

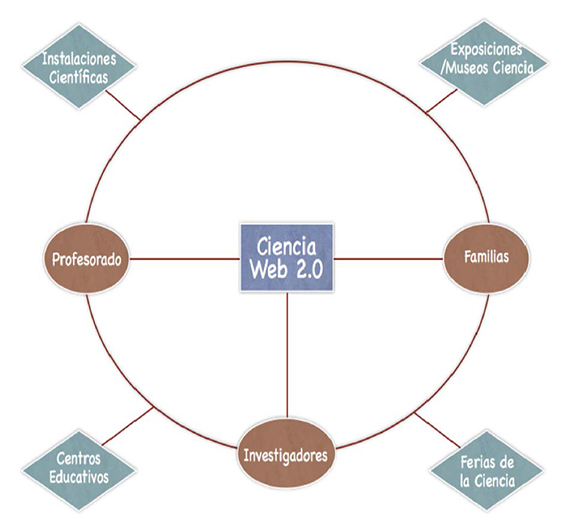

b) Web 2.0. For the system, a “web responsive” application was designed (adapted to smartphones and tablets) to allow access to the contents in an accessible and clear way. The web can be accessed by four types of user profiles: student, teacher, families, and pro-science centres (the latter is for personnel in museums, exhibitions, and scientific installations). The web environment has the main access to the control terminal from where there is access to relevant information such as:

• Active research: Eight real research projects were chosen from the 2014 and 2015 Spanish Antarctic Campaign. To select them, the curricular contents of the 3rd and 4th year of CSE in related subjects in the first term of the academic year were taken into account as well as their heterogeneity and repercussion on society. Dossiers were included about antecedents, how to deal with this problem, the need for research, its results, and social effect.

• CVs of the participating characters: Information about each of the characters. Three types of character were constructed: researchers, military personnel, and civilians. We collaborated with eight real researchers responsible for each one of the selected research projects, showing an informal CV for each with personal details, hobbies, their reasons for choosing research as a profession, etc. as well as a contact email address on the platform which could be used to ask them real doubts about their work as a researcher. Similarly, the CVs of the real military personnel of the active campaign were included, three from the Hespérides vessel, and three from the Gabriel de Castilla station. As civilians (not real ones), two protagonists were designed and three civilians completed the story.

• Installations: access to the game in the Hespérides vessel and the Gabriel de Castilla station, four scenarios in each one of these, perfectly recreated using photographs of these.

• Video blogs: weekly audiovisual reports to support the plot.

• Ranking: a table was completed with the ten best individual scores and for each school.

• Tasks: problems of a scientific nature to be resolved according to the needs of the story.

• News: a news bulletin that updated the story daily as the plot unfolded.

c) Game. Eight interactive scenarios were designed in a game format. Of these, four corresponded to the Hespérides and four to the Gabriel de Castilla station recreating real scenarios based on illustrations taken from photographs provided by the Army and Navy as a basis to work on. In each one of them, a scientific-type online challenge was planned to be carried out using the digital materials available in the available scenarios. Each scenario was coordinated according to the calendar, the research to be carried out, and the difficulty ratings of the game. At the start of the game, two scenarios were available (one in the Hespérides and another at the station) so that, depending on progression in the dynamics of the game, the other scenarios could be unlocked and points obtained.

In the different scenarios, elements were collected and combined so that it was possible to resolve the online challenges proposed (assay tubes, eyepieces, black light torch, etc.).

d) Protagonists. Two profiles were designed for the protagonists attending to the characteristics of the target population of the 3rd and 4th year of CSE paying special attention to the combination of pro-science interests, very up-to-date interests, and those that the target group could identify with. Boys and girls, students from Secondary Schools in the Region, both collaborated with the research teams of the Campaign. The two characters had profiles on social networks and undertook active communication with the participants (https://goo.gl/9vubBd).

e) Webisodes/video blogs. Fictional audiovisual materials with actors representing the protagonists and a post-production phase highlighting dramatized situations were coordinated with the story as triggers of moments in the story, generating or making way for problems that the participants had to decide how to resolve, choosing different alternatives before continuing. They can be seen on https://goo.gl/s76E6Q.

f) Challenges, tasks, and S&T curricular content. Obtaining points, insignias, or rewards were established attending to the two types of problems to be resolved. On the one hand, the online challenges were resolved in each scenario of the game (for example, analysing tissue samples from a penguin) providing individual scores. Once the challenge had been resolved, the weekly task was activated, a problem to be resolved similar to those seen in related subjects (resolving a ship’s steering angle needed to avoid a collision), and the answer to the challenge had to be entered while playing the game. Based on performance on these tasks, the score for the schools was obtained (scored according to the number of students in the 3rd and 4th year of CSE in the school). Only by resolving challenges and tasks was it possible to go to the next level. Both were published on Mondays at 9 a.m., with the activation of the corresponding video blog, reducing the points to be obtained in the following days. Support messages were programmed to be sent to the participants’ mobile phones and their twitter account. Similarly, if no response had been given by Thursday, a new videoblog was activated with clues to resolve the weekly challenge.

The complementary materials for the classroom designed using the curricular contents of the scientific subjects studied in the first term by the students on this project were aimed at: Natural sciences (3rd year CSE), biology and geology (4th year CSE), physics and chemistry (4th year CSE).

1) Extra teaching materials (for teachers, families, museums, ICTS). Materials to be used in the classroom were designed based on the curriculum contents of the 3rd and 4th years of the aforementioned subjects. A prior training activity was carried out for the teachers interested in participating (with more than 80 enrolled). As part of this activity, they were informed how the platform could be used. The teacher profile allows for the follow-up of students in his or her classes, monitoring of the results, errors, evolution, rewards, and other indicators.

Similarly, materials for families were designed using simple resources to develop contents or carry out experiments with homemade materials, and the like. These materials were distributed with plenty of time through the parent associations at the schools. Finally, the materials for pro-science schools (ICTS-Science Museums) were a collection of different resource packs organised in connection with the subject area of the project to create and revitalise workshops and visits.

2) Social Dynamics. Profiles were designed on the social networks of the protagonists of the story to complement it and make it more dynamic. A timeline was constructed for the communications made via social networks between the protagonists and participants, which was informal and mechanised, and linked to individual evolution in the game. The system made publications on Facebook or Twitter depending on weekly activity according to the storyline.

3) Values and attitudes. Having taken into account the previous relevance of attitudes and values in career decision-making, special care was taken in showing very up-to-date pro-science attitudes in the protagonists with common personalities and interests among the group. These were related to the real personalities of the scientists, attempting to move away from stereotypes about their image. The plot highlights the social benefits of the research done there, as well as the importance of taking care of the environment.

2.2. Study sample

Just as we have mentioned previously, the project was proposed to the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia, offering participation to all the secondary schools in the region through a public call for expressions of interest by the Local Education Authority. A maximum of 1,741 active students participated in the project resolving tasks and challenges every week (in addition to 465 teachers and 49 secondary schools). From these students, 100 participants were chosen at random to respond to an online survey with five questions at the beginning and the end of the project.

2.3. Procedure

The following questions were posed to the 100 selected participants:

• Have you heard about the research carried out by Spain in Antarctica?

• Do you know what takes place on the Hespérides vessel and at the Gabriel de Castilla station?

• Do the Army and Navy collaborate in the research carried out by Spain in Antarctica?

• Rank from 1 to 10 the benefit that you believe the research carried out in Antarctica provides for Spain?

• Would you like to be one of the scientists who do research work in Antarctica?

3. Analysis and results

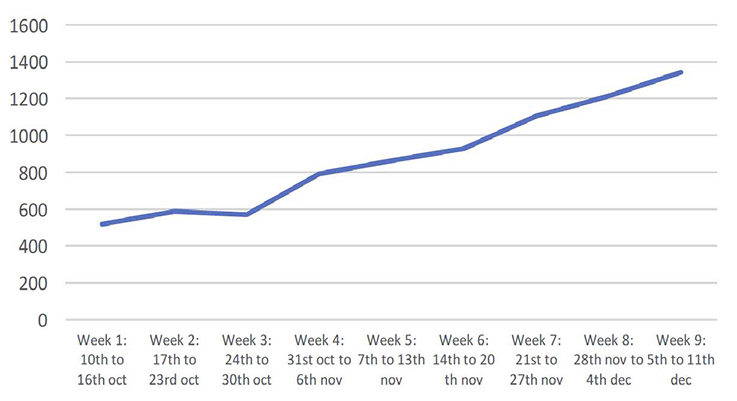

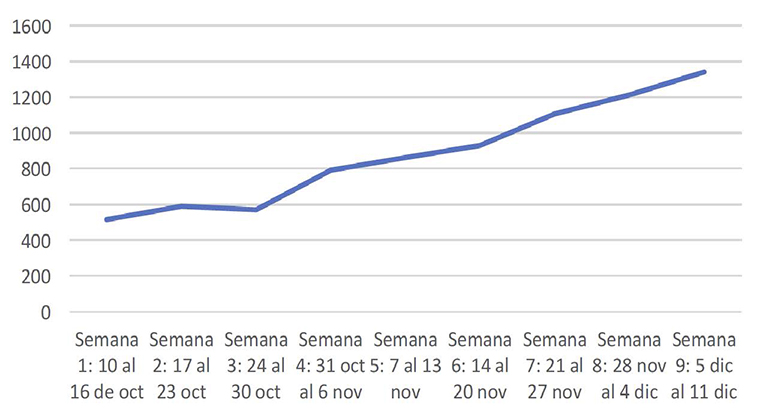

An analysis was carried out of the different participants’ access to the game and the resolution of the set challenges. The number of participants has been fairly constant, with mean weekly access of 1,503 students. It has been very useful to check how the number of entries in the last week is higher than in the first, suggesting the addition of participants once the project was underway. All of these indicators highlight that two elements of the project are working.

• The distribution of the contents and scaled levels subject to overcoming tasks. This has made it possible to maintain interest from week to week, “enticing” the users much more than if they had been shown all the scenarios and contents at the same time.

• The efficiency of the plot and scripting of the contents, meaning that one of the highest levels of entries took place the week it was resolved, with the identification of the guilty person. This was a good indicator of the immersion of the participants in the constructed story.

One important aspect regarding this information is the mean time dedicated by the participants to stay in the game. The mean staying time is directly related to the rate of difficulty. Therefore, its graphic representation should coincide with a fairly gradually ascending line. The data is shown in Figure 1.

As can be seen in the Figure, the line slowly increases so that the average time in the end doubles the average at the beginning. In light of this increase, we can see that the level of difficulty was correct regarding the development of an approach to the contents of the Project. We shall now analyse the data obtained by the selected sample in the pre- and post-project survey.

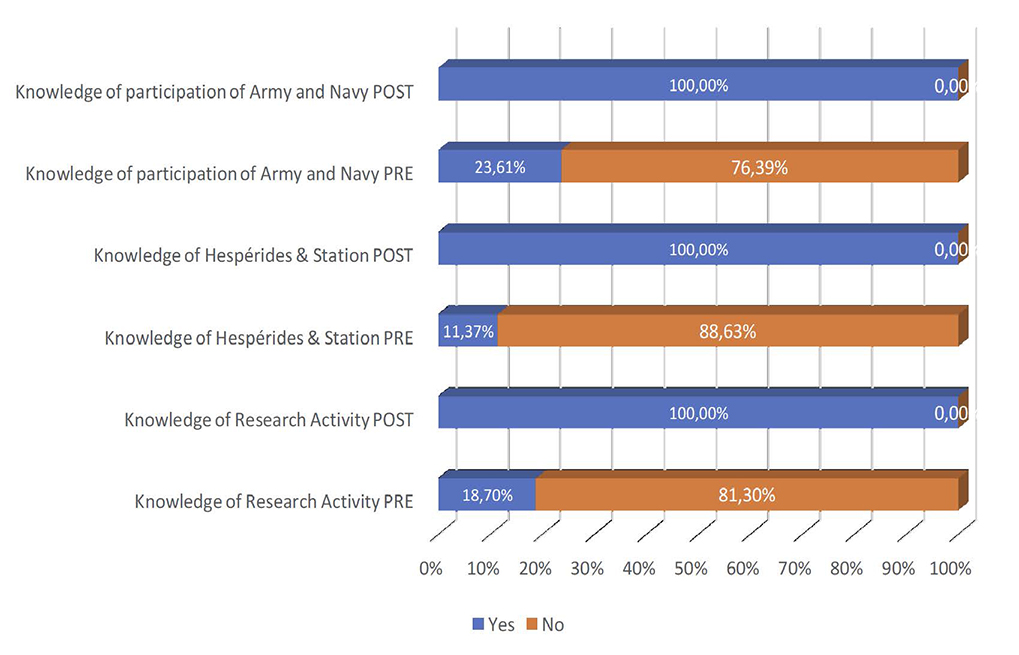

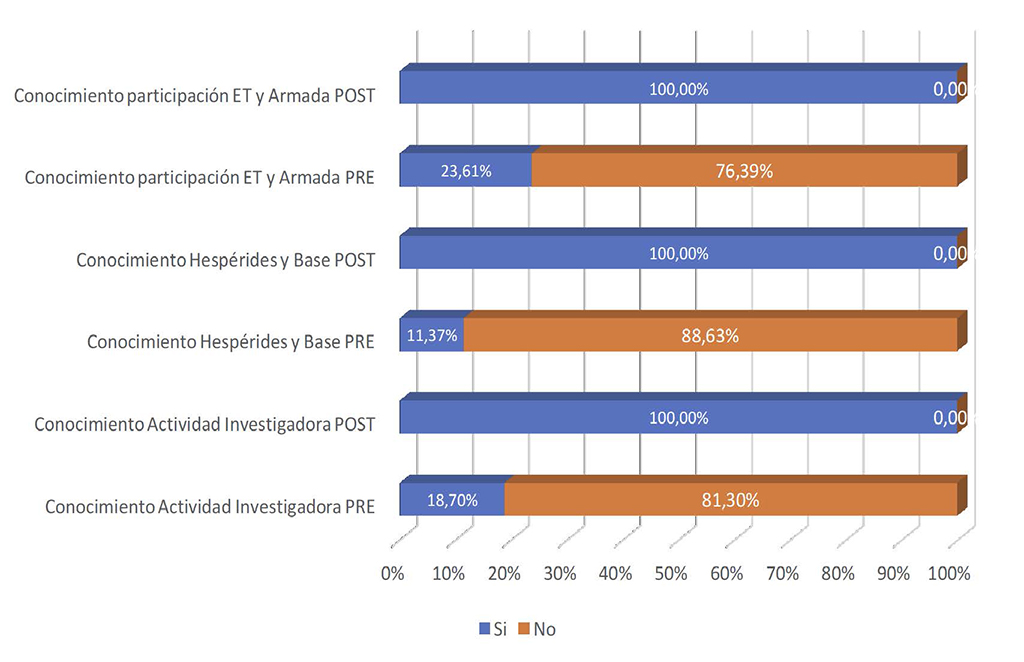

In Figure 2, we can see that initially, 18.7% of the participants knew about the research developed by Spain in Antarctica. After participation in the project, 100% knew about this work.

As in the previous question, we analysed the participant’s knowledge of the activity of the Hespérides and the Gabriel de Castilla station. Before participation in the project, 11.37% of them knew about it whereas, after participation in the project, 100% understood about this participation.

Likewise, the work of the Army and Navy in management, logistics, and in general support in the Spanish research work in Antarctica is usually quite unknown, and therefore it is interesting for us to find out about their previous knowledge and their evolution in the project. In Figure 2, we can see how only 23.61% of the participants stated knowing about the military and naval collaboration before the project. After participation, this percentage reached 100%.

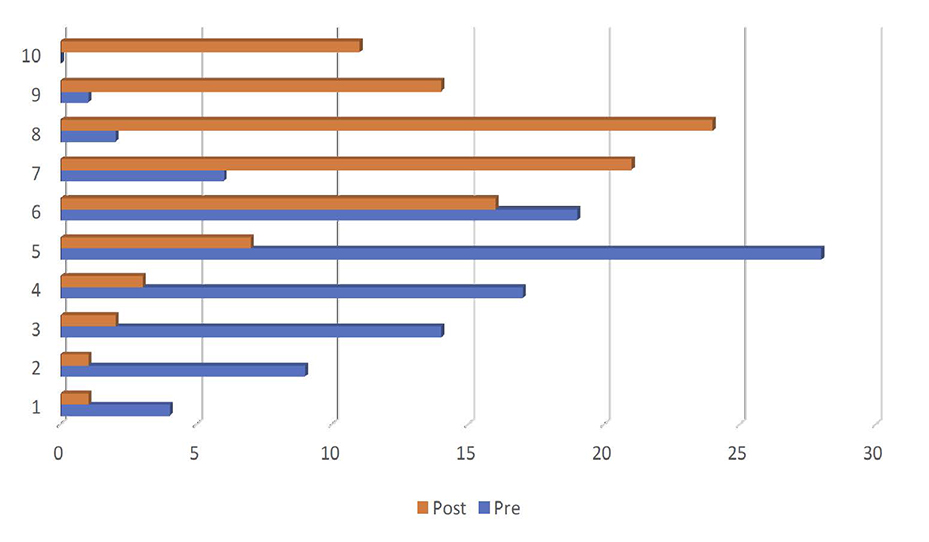

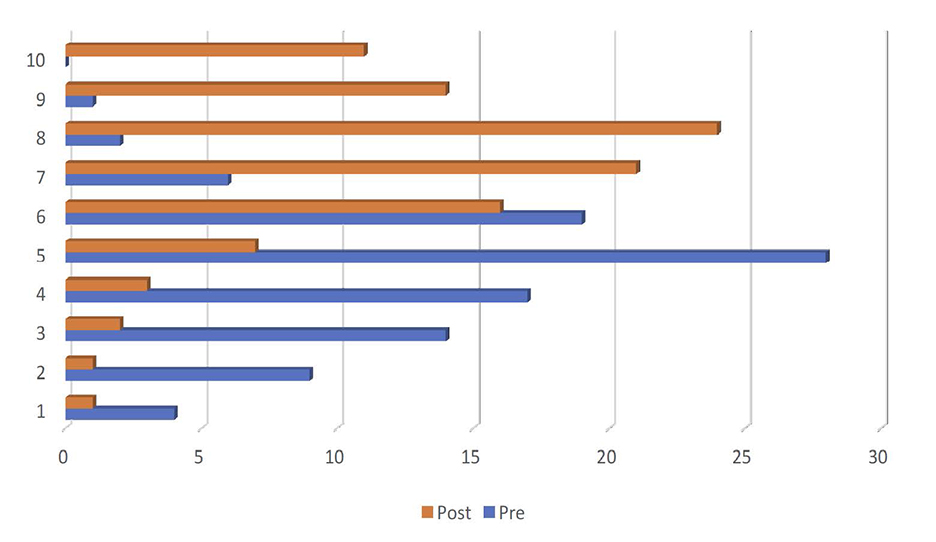

In this question, we observed scores (from 1 to 10) taken from the sample about the possible social impact of Antarctic research. As we can see, the pre-project assessment is quite harsh, with a mode of 5, and where the vast majority of scores are displaced towards the lowest scores. This contrasts with the post-project scores, where the mode is 8, and the score curve is displaced towards the upper zone.

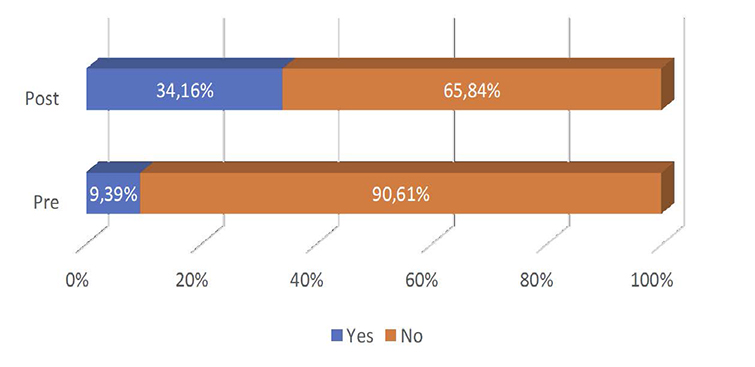

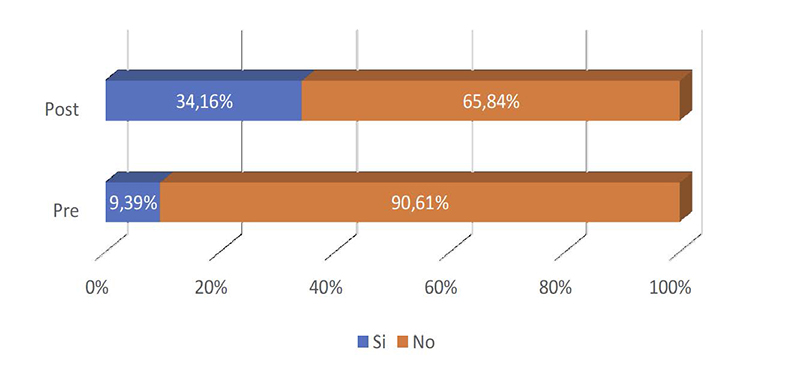

This is probably the most anticipated question of those posed, assessing the effect of the project on the participants’ interest in S&T careers. As we can see in Figure 4, previous interest in scientific professions was 9.39% in the pre-project sample, and after participation in this project, this percentage rose to 34.16%. We can see how professional interest in S&T has gone up very significantly.

4. Conclusions

Our general approach to the proposal was to follow a central element in gamification; according to (Hamari & Koivisto, 2013) “the main objective of gamification is to have an influence on people’s behaviour, regardless of other secondary objectives such as people’s enjoyment while taking part in the activity of the game”. Our proposal intended to go beyond the proliferation of game design elements that arise from the “do it yourself” techniques that we discussed at the outset. The limitations of this type of development are clear, restricting its reach, effects, and possibilities. The Antarctic Project has been the first experience of specifically designed transmedia gamification carried out in Spain for its mass application. For this reason, in its initial design elements could be taken into account that would have been difficult to include using more limited means, such as the transmedia component, the specially designed programming, or the involvement of pro-science entities, to name a few.

In the structure shown in Figure 5, we have considered the participation of all the players involved, each of them for different reasons. Institutionally, it is essential to coordinate scientific promotion campaigns among ICTS, science museums, fairs, and schools as a way to make the most of their efforts and to harmonise their interests, needs, shortcomings, and expectations. In scientific promotion and communication programs, it is necessary for scientists to be present as a way to eliminate classic stereotypes that persist today (scientist = clumsy, badly-dressed, not at all modern, etc.). The proximity of this group, its togetherness (the participants exchanged emails with the researchers about doubts and comments about their work), its interest of their work for society, etc. are key elements that were very evident in the program design.

In light of the results, we can confirm that we achieved the objectives we aimed at initially. The participants have had the opportunity to find out about the motivations for career-choices of active scientists and to see the interest and social benefit from research work in general while handling scientific methodology and learning about the work carried out at an ICTS. The previous lack of knowledge of Spanish research activity in Antarctica, the work of the Hespérides and the station, or the essential support of the Army and Navy are concerning and point toward the lack of knowledge affecting the heart of S&T actions and policies in Spain and, therefore, the decrease in demand for careers in this field. In this regard, our general objective of fostering vocational interest in S&T professional fields has been fulfilled with a clear and very relevant effect on the participants.

The use of elements close to the target user is of particular importance for achieving our objectives. It is essential to have an attractive storyline and, above all, to have protagonists the participants can easily identify with regarding likes, hobbies, and preferences. The use of messaging and publications on the protagonists’ social networks has greatly helped to increase the participants’ immersion and make the plot realistic. To do this, we must not forget the importance of illustrations and designs, a realistic reflection of real-life scenarios, even the complete 3D design of the Hespérides vessel and the Gabriel de Castilla station.

By carrying out this project, we have charted an especially interesting path for local authorities to carry out specially designed gamification programs with transmedia support, involving all the players in a common and coordinated effort. The initial financial cost is quickly overcome in the following years, repeating the story in different groups of students, or only changing the plot and characters. A project of this nature can make way for changes in the story by multiplying different developments that use the same core software. The efficient use of public investment in these tools is inevitable if we want to implement efficient and innovative technology in education that goes beyond isolated individual experiences.

Funding agency

A project encouraged and financed by Telefónica Foundation with the participation of the Education Authority of the Region of Murcia (through the Seneca Foundation, the Regional Science and Technology Agency) and in collaboration with the Spanish Polar Committee and the Spanish Army and Navy.

References

All, A., Nunez-Castellar, E.P., & Van-Looy, J. (2014). Measuring effectiveness in digital game-based learning: A methodological review. International Journal of Serious Games, 1(2), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v1i2.18

Berkling, K., & Thomas, C. (2013). Gamification of a software engineering course and a detailed analysis of the factors that lead to it’s failure. International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning, ICL 2013, 525-530. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICL.2013.6644642

Brewer, R., Anthony, L., Brown, Q., Irwin, G., Nias, J., & Tate, B. (2013). Using gamification to motivate children to complete empirical studies in lab environments. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children - IDC ’13 (pp. 388-391). https://doi.org/10.1145/2485760.2485816

Chorney, A.I. (2012). Taking the game out of gamification. Dalhousie Journal of Interdisciplinary Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.5931/djim.v8i1.242

Coll, C., Mauri-Majós, M.T., & Onrubia-Goñi, J. (2008). Analyzing actual uses of ICT in formal educational contexts: A socio-cultural approach. Revista Electronica de Investigacion Educativa, 10(1), 1-18.

De-Pro, A., & Pérez, A. (2014). Actitudes de los alumnos de Primaria y Secundaria ante la visión dicotómica de la ciencia. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 32(3), 111-132. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/ensciencias.1015

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference on Envisioning Future Media Environments - MindTrek ’11 (p. 9). https://doi.org/10.1145/2181037.2181040

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2015). Gamification in Education: A systematic Mapping Study. Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 75-88. doi:10.1145/2554850.2554956

Domínguez, A., Saenz-De-Navarrete, J., De-Marcos, L., Fernández-Sanz, L., Pagés, C., & Martínez-Herráiz, J.J. (2013). Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Computers and Education, 63, 380-392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.020

Ferro-Soto, C.A., Martínez-Senra, A.I., & Otero-Neira, M.C. (2009). Ventajas del uso de las TIC en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje desde la óptica de los docentes universitarios españoles. Edutec, 29, 5. https://doi.org/10.21556/edutec.2009.29.451

Foncubierta, J.M., & Rodríguez, C. (2014). Didáctica de la gamificación en la clase de español. Madrid: Edi Numen, 1-8.

García-Valcárcel, A., Basilotta, V., & López-García, C. (2014). Las TIC en el aprendizaje colaborativo en el aula de Primaria y Secundaria [ICT in collaborative learning in the classrooms of Primary and Secondary]. Comunicar, 42, 65-74. https://doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-06

Gibson, D., Ostashewski, N., Flintoff, K., Grant, S., & Knight, E. (2013). Digital badges in education. Education and Information Technologies, 20(2), 403-410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-013-9291-7

Gros, B., & Bernat, A. (2008). Videojuegos y aprendizaje. Barcelona: Grao´. (https://goo.gl/NQ6izd).

Hamari, J., & Koivisto, J. (2013). Social motivations to use gamification: An empirical study of gamifying exercise. Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on Information Systems Social, (June), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.031

Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2012). Defining gamification. In Proceeding of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Conference on - MindTrek ’12 (p. 17). https://doi.org/10.1145/2393132.2393137

Kapp, K.M. (2012). Games, gamification, and the quest for learner engagement. T+D, 6(June), 64-68. (https://goo.gl/VV4GTq).

Murphy, C., & Beggs, J. (2003). Children´s perceptions of school science. School Science Review, 84, 108-116.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). The concept of flow NIMM “Flow Theory and Research”. Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 195-206. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0018

O’Donovan, S., Gain, J., & Marais, P. (2013). A case study in the gamification of a university-level games development course. Proceedings of the South African Institute for Computer Scientists and Information Technologists Conference on - SAICSIT ’13, 242. https://doi.org/10.1145/2513456.2513469

Pérez-Manzano, A. (2013). Actitudes hacia la ciencia en primaria y secundaria. TDR (Tesis Doctorales en Red). (https://goo.gl/Em2zou).

Perrotta, C., Featherstone, G., Aston, H., & Houghton, E. (2013). Game-based learning: Latest evidence and future directions. (NFER Research Programme: Innovation in Education). Slough: NFER. (https://goo.gl/D6cmdq).

Pink, D.H. (2011). Drive: the surprising truth about what motivates us. New York: Riverhead.

Prosperti, C.A., Sabarots, G.J., & Villa, M.G. (2016). Uso de la gamificación para el logro de una gestión empresarial integrada. Perspectivas de las Ciencias Económicas y Jurídicas, 6(2), 83-97. https://doi.org/10.19137/perspectivas-2016-v6n2a05

Raymer, R. (2011). Gamification: Using game mechanics to enhance eLearning. eLearn, 2011(9), 3. https://doi.org/10.1145/2025356.2031772

Santos, C., Almeida, S., Pedro, L., Aresta, M., & Koch-Grunberg, T. (2013). Students’ perspectives on badges in educational social media platforms: the case of SAPO campus tutorial badges. Proceedings IEEE 13th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, ICALT 2013, 351-353. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALT.2013.108

Schreiner, C., & Sjøberg, S. (2005). Sowing the Seeds of ROSE. Background, rationale, questionnaire development and data coolection for ROSE (The Relevance of Science Education). A comparative study of students’ views od science and science education. Acta Didactica, 4. Oslo: University of Oslo. (https://goo.gl/MLSbFG).

Scolari, C.A. (2013). Narrativas transmedia: cuando todos los medios cuentan. Bilbao: Deusto.

Sjøberg, S. (2000). Science And scientists: The SAS-study. Cross-cultural evidence and perspectives on pupils’ interests, experiences and perceptions. Acta Didactica, 1. Oslo: University of Oslo. (https://goo.gl/i5Y7Hd).

Vázquez-Alonso, Á., & Manassero-Mas, M.A. (2009). La relevancia de la educación científica: Actitudes y valores de los estudiantes relacionados con la ciencia y la tecnología. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 27(1), 33-48. (https://goo.gl/NADatr).

Wiggins, B.E. (2016). An overview and study on the use of games, simulations, and gamification in higher education. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 6(1), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGBL.2016010102

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

En la actualidad la proliferación de aplicaciones basadas en gamificación y especialmente en el denominado Aprendizaje Digital Basado en Juegos (Digital Game-Based Learning, DGBL) abre un panorama de elevado potencial educativo. En el presente trabajo se muestran los resultados del desarrollo de un proyecto con el funcionamiento de un entorno web gamificado y realizado ad hoc, complementado con recursos transmedia y dirigido a la divulgación científica y al fomento de las vocaciones científico-tecnológicas (CyT) en adolescentes, siendo precisamente en este rango de edad donde se configura la preferencia vocacional. El descenso de vocaciones CyT supone uno de los mayores problemas actuales para la sociedad de desarrollo tecnológico en la que nos encontramos, con un descenso generalizado de profesionales en áreas claves para el desarrollo económico y de progreso. Tras la realización de una encuesta previa a la participación en el proyecto y la misma encuesta tras la realización del mismo, los resultados obtenidos indican la elevada eficacia de proyectos de este tipo, diseñados en base a la experimentación online, el conocimiento de situaciones reales de la actividad investigadora y la comunicación de valores y actitudes procientíficas de forma afín a la población objetivo. Los participantes aumentan significativamente su interés por la profesión científica, la actividad investigadora y su beneficio social manifestando la adquisición de conocimientos y destrezas procientíficas y poniendo de relieve su interés por la temática tratada.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

La progresiva introducción de las tecnologías de la información y las comunicaciones (TIC) en el ámbito educativo supone el mayor desafío actual en esta área. Como cualquier modificación metodológica a gran escala no está exenta de controversias, falta de recursos, desinformación, resistencias de todo orden, etc. Las administraciones educativas, generalmente escasas de recursos y de creatividad, abogan, cómodamente, por la postura del «do it yourself», convenciendo al profesorado de que forma parte de sus atribuciones el innovar, aprender herramientas TIC novedosas e implantarlas en su aula o centro. Se suele olvidar, por ejemplo, que la preparación y el uso de las TIC requiere de mayor tiempo de dedicación del profesor que las metodologías docentes convencionales (Ferro-Soto, Martínez-Senra, & Otero-Neira, 2009) «el uso de las TIC puede llegar a restar tiempo para dedicarse a otro tipo de tareas que oficialmente se le reconocen al docente». No obstante, queda fuera de toda duda el enorme potencial que ofrecen las TIC a nivel educativo, creando entornos digitales de encuentro, aprendizaje colaborativo, mediación social y favoreciendo un aprendizaje transversal, trabajando valores prosociales, actitudes personales y una visión menos compartimentada de los contenidos. Considerar las TIC como herramientas pedagógicas supone entender que aportan mejores canales de comunicación educativa (Coll, Mauri-Majós, & Onrubia-Goñi, 2008), de hecho García-Valcárcel, Basilotta y López-Salamanca (2014) abogan por «la imprescindible transformación de las prácticas escolares, fomentando el desarrollo de proyectos colaborativos donde las TIC se conviertan en un canal de comunicación y de información imprescindible para garantizar unos escenarios de aprendizaje abiertos, interactivos, ricos en estímulos y fuentes de información, motivadores para el alumnado, centrados en el desarrollo de competencias».

La gamificación es, posiblemente, la herramienta metodológica que más atención ha recibido y se ha considerado más relevante para su implantación en educación (Dicheva, Dichev, Agre, & Angelova, 2015; Wiggins, 2016). En los últimos años hemos asistido a una explosión del término en revistas especializadas que presentan la gamificación como el nuevo método clave en educación, en entornos escolares y, particularmente, en empresariales (Prosperti, Sabarots, & Villa, 2016).

1.1. Elementos del aprendizaje basado en juegos

La gamificación se ha venido definiendo tradicionalmente como la aplicación de elementos del entorno de juegos en actividades que no son de juego y en diferentes contextos, incluido por supuesto el educativo. Su objetivo principal es el de mejorar la motivación intrínseca de los participantes. Diferentes autores han colocado el acento en distintos elementos de la misma; para Huotari y Hamari (2012) es de resaltar la relevancia de la evocación, desde los procesos gamificados, de las mismas experiencias psicológicas a que dan lugar los juegos; por otra parte, Deterding, Dixon, Khaled y Nacke (2011) enfatizan la importancia de que los elementos implementados en el proceso gamificador sean los mismos que los usados en los juegos, con independencia de los resultados.

Para Perrotta, Featherstone, Aston y Houghton (2013), el denominado «Aprendizaje Digital basado en Juegos» (Digital Game-based Learning, DGBL) se desarrolla en base a principios y mecanismos esenciales que articulan su efectividad. Como principios, Perrotta señala cinco:

• Motivación intrínseca. Mucho más potente que la motivación extrínseca, la motivación intrínseca parte de la voluntariedad del jugador en participar, el juego invita y persuade para su uso. Según Pink (2011) la motivación intrínseca está relacionada con tres elementos que la inducen: autonomía, competencia y finalidad.

• Aprendizaje a través del disfrute intenso. Para una corriente de autores, encabezados por Csikszentmihalyi (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2009), el juego involucra a los participantes en un flujo (Teoría del Flujo), considerado este como un estado de conciencia en el que el individuo mantiene el control de sus acciones y está completamente absorbido por la tarea que realiza. Csikszentmihalyi señala ocho componentes que posibilitan el flujo: que la tarea sea realizable, concentración, objetivos claros, existencia de feedback, involucración sin esfuerzo, control sobre las acciones que se realizan, desaparición de la consciencia de uno mismo, y pérdida del sentido del tiempo.

• Autenticidad. Preocupación por la naturaleza real del aprendizaje frente a las formas más artificiales y descontextualizadas de la enseñanza tradicional. Prioridad de las habilidades contextuales frente a las nociones abstractas del aprendizaje formal. Procesos de aprendizaje basados en prácticas específicas.

• Autonomía. El juego anima a la exploración independiente, pudiendo confluir en él intereses y preferencias personales, especialmente en el ecosistema que lo rodea, tales como habilidades técnicas y artísticas, escritura, dibujo, música, pero también el interés por conseguir más información sobre otros temas, como, por ejemplo, ciencia o historia.

• Aprendizaje experiencial. El juego ofrece la posibilidad de enfrentarse a situaciones en las que el «aprender haciendo» es una opción tangible, programable y dirigible.

A la vista de la literatura sobre el tema, podemos identificar ocho elementos esenciales del diseño de juegos que se suelen aplicar en contextos educativos (en los DGBL):

• Puntos. Suponen una valoración cuantitativa de los avances conseguidos por el jugador y suelen ser utilizados como recompensa inmediata por su esfuerzo y como un elemento proactivo para la evolución del jugador en el juego.

• Niveles. Los niveles se han utilizado habitualmente para mostrar la progresión en el desarrollo del juego. Generalmente se han considerado como sinónimos del grado de dificultad. El ascenso de nivel sirve como una forma de recompensa común en los juegos, utilizada en el momento de completar tareas o misiones. Es muy importante el ajuste del grado de dificultad para el tránsito de niveles para evitar el abandono y/o la desmotivación de los participantes (All, Nunez-Castellar, & Van-Looy, 2014).

• Insignias y distintivos. Se consideran como una representación visible de un logro obtenido destinado a mantener en niveles adecuados la motivación del jugador para las siguientes tareas (Gros & Bernat, 2008). Las insignias son eficaces sobre todo para focalizar el interés del jugador en resolver futuros retos u objetivos (Chorney, 2012; Santos, Almeida, Pedro, Aresta, & Koch-Grunberg, 2013).

• Tablas de clasificación. Favorecen la motivación de los participantes, incentivando su rendimiento en el juego como forma de ir ganando posiciones. Muestra las mejores puntuaciones de los participantes, actualizándose con regularidad. Según O’Donovan, Gain y Marais (2013) aumenta claramente la motivación de los participantes en desarrollos gamificados educativos.

• Premios y recompensas. El uso de premios y beneficios en el juego se ha confirmado como un motivador potente para los participantes (Brewer & al., 2013) de ahí la especial relevancia de la temporalización y el grado de las recompensas a obtener en el nivel de motivación de los jugadores (Raymer, 2011). El calendario de recompensas se debe ajustar en función de los contenidos educativos, dificultad de las tareas y niveles del juego, previendo posibles zonas de desmotivación o cansancio (Gibson, Ostashewski, Flintoff, Grant, & Knight, 2013).

• Barra de progreso. Muestra el avance del desarrollo del juego, en qué nivel se encuentra el jugador, cuánto ha avanzado y cuánto le queda.

• Argumento. La historia que subyace al juego y que le dota de sentido. Kapp (2012) sugiere que un buen argumento ayuda a los participantes a alcanzar una buena curva de interés, manteniéndolo vivo durante todo el juego, aumentando las posibilidades de alcanzar el final y reduciendo los abandonos. El argumento también aporta un contexto muy aprovechable para el aprendizaje, la solución de problemas, la simulación, etc. permitiendo ilustrar y practicar la aplicabilidad de los conceptos.

• Feedback. La información de retorno de la actividad del jugador. Su eficacia dependerá de su frecuencia, intensidad e inmediatez (Raymer, 2011; Kapp, 2012; Berkling & Thomas, 2013). Mayor frecuencia e inmediatez se relacionan con mejores resultados en el proceso gamificado de aprendizaje. Asimismo, el feed-back es un importante indicador de eficacia e inmersión en la dinámica de juego (Domínguez & al., 2013).

Una vez configurados los elementos esenciales de un producto de Aprendizaje Digital Basado en Juegos (DGBL) es relevante comprobar cómo potenciar sus efectos y, particularmente, el área ideal para su aplicación (Foncubierta & Rodríguez, 2014).

1.2. El componente transmedia

El término «narrativas transmedia» fue introducido por Henry Jenkins (2003), en un artículo publicado en «Technology Review», donde señalaba que «hemos entrado en una nueva era de convergencia de medios que vuelve inevitable el flujo de contenidos a través de múltiples canales». Según Jenkins las narrativas transmedia son «historias contadas a través de múltiples medios». Para Scolari (2013), las narrativas transmedia suponen «una particular forma narrativa que se expande a través de diferentes sistemas de significación (verbal, icónico, audiovisual, interactivo, etc.)».

Posteriormente a su artículo, Henry Jenkins definió los principios fundamentales de las narrativas transmedia:

• Expansión vs. profundidad: Expansión viral mediante redes sociales vs penetración en las audiencias hasta encontrar incondicionales.

• Continuidad vs. Multiplicidad: Continuidad de expresión en lenguajes, medios y plataformas vs multiplicidad de creación de experiencias a partir del argumento inicial.

• Inmersión vs. Extraibilidad: Inmersión en el argumento propuesto vs extracción de elementos del relato para encajarlos en el mundo real.

• Construcción de mundos: Elaboración de características que enriquecen y dan verosimilitud al relato, como detalles de los personajes, entornos, etc.

• Serialidad: Organización de las piezas y elementos del relato principal en una secuencia que involucra a diferentes medios.

• Subjetividad: Mezcla de subjetividades múltiples en cuanto a personajes e historias participantes del relato nuclear.

• Realización: Los consumidores del relato pueden promover y promocionar la historia principal incluso convirtiéndose en creadores de contenidos afines y complementarios (prosumidores, según Jenkins).

La combinación de principios de gamificación y narrativas transmedia ofrece un universo educativo de una potencia inabarcable y que encaja y corresponde con el perfil de usuario al que nos dirigimos en el entorno educativo: un usuario multiplataforma, inmersivo, que gestiona demandas múltiples a gran velocidad, que prefiere personalizar y gestionar sus experiencias, haciéndolas propias y participando/creando en ellas de forma activa. El educando pasivo hace tiempo que es historia.

1.3. Divulgación científica, actitudes y vocaciones procientíficas

Las actitudes de la población hacia la ciencia no solo pueden condicionar el rendimiento escolar en las asignaturas de ciencias, sino la forma de pensar y hacer de la sociedad, su imagen social –y, en consecuencia, el apoyo socioeconómico a las investigaciones y programas científicos– o la cantidad de investigadores o profesionales en este campo de conocimiento (Pérez-Manzano, 2013). Unido a ello cobra especial relevancia el persistente descenso de vocaciones CyT (ya constatado en un informe de la Comisión Europea en 2004) que contrasta con el incremento de la demanda de profesiones CyT.

La relación entre actitudes hacia la ciencia y vocaciones CyT es clara y como consecuencia de ello la elevada producción científica generada nos ha aportado distintos elementos de partida:

• En el proyecto ROSE (Schreiner & Sjøberg, 2005) se muestran «ciertas tendencias o regularidades», como por ejemplo que se dé una relación inversa entre el grado de desarrollo del país y las actitudes positivas hacia la ciencia en jóvenes estudiantes de secundaria (Sjøberg, 2000; Schreiner & Sjøberg, 2005). El descenso de actitudes procientíficas conlleva consecuencias en la selección o rechazo de asignaturas y contenidos científicos en primera instancia, en el número de vocaciones profesionales e incluso generando perfiles personales pro o anticientíficos estables.

• La toma de decisión vocacional va adquiriendo solidez entre los 14-16 años, es decir, 3º y 4º de Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria.

• La variable género es muy relevante. La imposición de estereotipos, tópicos y tradiciones sociales a la hora de vincular determinadas profesiones a esta variable (Murphy & Beggs, 2003; Vázquez-Alonso & Manassero-Mas, 2009).

• Un componente importante en la toma de decisión vocacional de las chicas es el beneficio social de la profesión elegida, así como el contacto con los demás debido al ejercicio profesional de la misma (De-Pro & Pérez, 2014).

2. Material y métodos

A la vista del marco anteriormente expuesto nos planteamos la necesidad de realizar un proyecto que posibilitara la promoción de la actividad científica desde un desarrollo gamificado con refuerzo transmedia que permitiera una experiencia inmersiva y participativa.

Planteamos como objetivo general el fomento de las vocaciones científico-tecnológicas mediante el abordaje de tres componentes, habitualmente identificados en las investigaciones sobre el tema como esenciales para la configuración de una vocación científico-tecnológica clara:

• Componentes vocacionales de científicos en activo.

• Interés del trabajo diario real de un investigador.

• Beneficio social de la actividad científica.

Estos se verán reforzados por dos objetivos transversales complementarios, como son el manejo de metodología científica y el conocimiento de las instalaciones científico-técnicas singulares (ICTS) vinculadas a la Región de Murcia (el Buque de Investigación Oceanográfica Hespérides y, por ende, las bases antárticas) así como las investigaciones desarrolladas desde ellas y su repercusión social consecuente. Las ICTS son instalaciones científicas de primer nivel nacional e internacional que, por sí solas, aglutinan la mayor parte del presupuesto científico del país y que, en diferentes estudios previos (Pérez-Manzano, 2013; De-Pro & Pérez, 2014) aparecían como completamente desconocidas para la población en general y para los estudiantes de ESO en particular.

Le asignamos a la propuesta la denominación de Proyecto Antártica. Una vez elaborada y presentada, es aceptada para su realización por la Fundación Telefónica con la participación de la Consejería de Educación de la Región de Murcia (por medio de la Fundación Séneca, Agencia Regional de Ciencia y Tecnología) y la colaboración del Comité Polar, la Armada y el Ejército de Tierra. Se plantea una aplicación circunscrita a los IES de la Región de Murcia.

2.1. Metodología

El Proyecto Antártica comprende una gran diversidad de materiales a medida, diseñados en base y como refuerzo a una línea argumental con capacidad de atraer a la población objetivo. A continuación, se detallan sus componentes:

a) Trama argumental. Dado que todo el desarrollo de materiales gira en torno a una línea argumental resultaba muy importante la construcción de la misma y que la cantidad de materiales transmedia elaborados resultaran convergentes en ella. Como hilo conductor se decidió narrar una situación en la que se han producido diferentes sabotajes en instalaciones del Hespérides y la Base Gabriel de Castilla, encaminadas a destruir instalaciones científicas o desarrollos de investigación en activo. Se transmite la idea de la existencia de un saboteador interesado en eliminar la actividad investigadora en la Antártica. Conforme avance la trama argumental los participantes podrán comprobar la relevancia social de las investigaciones allí realizadas además de los intereses poco éticos en el continente Antártico (utilización turística indiscriminada o deterioro medioambiental). Se ha cuidado la línea de tiempo argumental para su coordinación con contenidos, nivel de dificultad, noticias, comunicaciones, etc.

Al desarrollo de la trama le ha correspondido la responsabilidad, clave en un proyecto de este tipo, de garantizar el nivel de inmersión en la historia utilizada, reforzando la participación y reduciendo los abandonos en el desarrollo del proyecto, manteniendo el interés y la motivación de los participantes a lo largo de los tres meses de ejecución del Proyecto.

b) Web 2.0. Para el sistema se elaboró una aplicación «web responsive» (adaptada a smartphones y tablets) que permitiera acceder a los contenidos de forma accesible y clara. La web dispone de accesos para cuatro perfiles de usuario: estudiante, profesor, familias y centros procientíficos (este último pensado para personal de museos, exposiciones o instalaciones científicas). El entorno web dispone de un acceso principal a la terminal de control desde donde se accede a información relevante como:

• Investigaciones en activo: Se eligieron ocho investigaciones reales desarrolladas en Campaña Antártica en 2014 y 2015. Para su selección se tuvieron en cuenta los contenidos curriculares de 3º y 4º de ESO en las asignaturas afines en el primer trimestre del curso, así como su heterogeneidad y su repercusión en la sociedad. Se incorporaron dossiers sobre antecedentes, planteamiento del problema, necesidad de la investigación, resultados y efecto social.

• Currículums de personajes participantes: Información sobre cada uno de los personajes. Se diseñaron tres tipos de personajes: investigadores, personal militar y civiles. Se contó con ocho investigadores reales, responsables de cada una de las investigaciones seleccionadas, mostrando un currículum informal con detalles personales, hobbies, sus motivaciones para elegir la investigación como opción profesional, etc. además de un correo de contacto en la plataforma desde el que poderles preguntar dudas reales sobre su trabajo investigador. Así mismo se incluyó CV del personal militar real de la campaña en activo, tres del buque Hespérides y tres de la Base Gabriel de Castilla. Como personal civil (no real) se diseñaron dos protagonistas y tres civiles que complementaban la trama.

• Instalaciones: acceso a la aventura gráfica en el Buque Oceanográfico Hespérides y la Base Gabriel de Castilla, cuatro escenarios de cada uno de ellos, perfectamente recreados utilizando fotografías de los mismos.

• Videoblogs: audiovisuales semanales de refuerzo a la trama argumental.

• Ranking: tabla con las diez mejores puntuaciones individuales y de centro.

• Tareas: problemas de carácter científico a resolver de acuerdo con las necesidades de la trama argumental.

• Noticias: boletín de noticias relacionadas con la trama argumental, actualizable a diario en función de la evolución de la historia.

c) Aventura gráfica. Se elaboraron ocho escenarios interactivos en formato aventura gráfica. De ellos, cuatro correspondían al Hespérides y cuatro a la Base Gabriel de Castilla recreándose escenarios reales de los mismos en ilustración tomando como base fotografías aportadas por la Armada y el ejército de Tierra. En cada uno de ellos se planificó un reto online de carácter científico a realizar con los materiales digitales disponibles en los escenarios disponibles. Se coordinó cada escenario con el calendario, investigaciones a realizar e índice de dificultad del juego. Se iniciaba con dos únicos escenarios disponibles –uno en el Hespérides y otro en la Base– para, en función de la progresión en la dinámica de juego, ir desbloqueando los restantes y obteniendo puntos.

En los diferentes escenarios se recogían elementos con los que, mediante su combinación, se podían resolver los retos online propuestos (tubos de ensayo, oculares, linterna de luz negra, etc.)

d) Protagonistas. Se diseñaron dos perfiles protagonistas atendiendo a las características de la población objetivo de 3º y 4º de ESO prestando especial atención a la combinación de intereses procientíficos con intereses muy actuales y con los que el target se pudiera identificar. Chico y chica, estudiantes de centros de Secundaria de la Región, ambos colaboradores en los equipos de investigadores de la Campaña. Los dos personajes contaron con espacios en redes sociales y comunicación activa con los participantes (https://goo.gl/9vubBd).

d) Webisodios/videoblogs. Audiovisuales de ficción con actores representando a los personajes protagonistas y con postproducción de realce mostrando situaciones dramatizadas coordinadas con la trama argumental como disparadores de momentos de la historia, generando o dando pie a problemas que los participantes deberán decidir cómo resolver, eligiendo diferentes alternativas para continuar. Se pueden ver en https://goo.gl/s76E6Q.

e) Retos, tareas y contenidos curriculares CyT. La obtención de puntos, insignias o beneficios se diseñó atendiendo a dos recursos. Por una parte, los retos online a resolver en cada escenario de la aventura gráfica (por ejemplo: analizar las muestras de tejido de un pingüino) aportaban las puntuaciones individuales. Una vez resuelto el reto, se activaba la tarea semanal, un problema a resolver del estilo de los planteados en las asignaturas relacionadas (resolver el ángulo de viraje del barco para evitar una colisión) y donde debían introducir la respuesta correcta en el sistema. De las tareas se obtenía la puntuación de los centros (baremada en función del volumen de alumnos en 3º y 4º de ESO en el centro). Solo resolviendo retos y tareas se conseguía acceder al siguiente nivel. Ambos se publicaban los lunes a las 9:00 h., con la activación del videoblog correspondiente, reduciéndose los puntos a obtener con el transcurso de los días. Se programaron mensajes de refuerzo al móvil de los participantes y a su cuenta de twitter. De igual manera, en el caso de no haber respondido el jueves, se activaba un nuevo videoblog con pistas para la resolución del reto semanal.

Los materiales complementarios para el aula se elaboraron con los contenidos curriculares del primer trimestre de las asignaturas científicas a las que se dirige el Proyecto: Ciencias de la naturaleza (3º ESO), biología y geología (4º ESO), física y química (4º ESO):

a) Materiales didácticos extra (profesorado, familias, museos, ICTS). Se elaboran materiales para la explotación en el aula de los contenidos curriculares de 3º y 4º de las asignaturas anteriormente citadas. Se realizó una actividad formativa previa a los profesores interesados en participar (con más de 80 inscritos). En dicha actividad se les formó sobre el uso y explotación de la plataforma; el perfil profesor permite el seguimiento de los estudiantes de sus clases, monitorización de resultados, errores, evolución, recompensas, etc.

De igual forma, se elaboraron materiales para familias, distribuidos con suficiente antelación mediante las AMPAS de los centros, con recursos sencillos para la explotación de contenidos, realización de experimentos con material casero, etc. Por último, los denominados materiales para centros procientíficos (ICTS-Museos de la Ciencia) agrupan diferentes packs de recursos para la creación y dinamización de talleres o visitas organizadas bajo la temática del proyecto.

b) Dinamización social. Se elaboraron perfiles en las redes sociales de los protagonistas de la trama argumental como complemento y dinamización de la misma. Se diseñó una línea de tiempo para las comunicaciones vía redes sociales entre protagonistas y participantes, desatendida y mecanizada, vinculada a la evolución individual en el juego. El sistema realizaba publicaciones en Facebook o Twitter en función de la actividad semanal según la línea argumental.

c) Valores y actitudes. Habida cuenta de la relevancia previa de las actitudes y valores en la toma de decisión vocacional, se tuvo especial cuidado en mostrar actitudes procientíficas en protagonistas muy actuales, con personalidades e intereses habituales entre el colectivo. Vinculado con las personalidades reales de los científicos, pretendiendo alejar estereotipos en la imagen de los mismos. Con especial relevancia se mostraron en la trama argumental los beneficios sociales de las investigaciones allí realizadas, así como del respeto al medio ambiente.

2.2. Muestra del estudio

Tal como hemos citado anteriormente, se plantea la realización del proyecto en la Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia, ofertándose la participación en el mismo a todos los IES de la Región mediante convocatoria pública de la Consejería de Educación. El proyecto contó con un máximo de 1.741 estudiantes activos semanalmente resolviendo tareas y retos (además de 465 profesores y 49 centros de Secundaria). De estos estudiantes se seleccionaron, de forma aleatoria, a 100 participantes para responder de forma online a una encuesta de cinco preguntas al inicio y al final del proyecto.

2.3. Procedimiento

Las preguntas planteadas a los 100 seleccionados fueron las siguientes:

• ¿Conoces la actividad investigadora de España en la Antártida?

• ¿Conoces a qué se dedican el Buque Oceanográfico Hespérides y la Base Gabriel de Castilla?

• ¿El Ejército de Tierra y la Armada colaboran en la investigación que hace España en la Antártida?

• Valora de 1 a 10 el beneficio que crees que aportan a la sociedad las investigaciones realizadas por España en la Antártida.

• ¿Te gustaría ser uno de los científicos/as que realizan investigaciones en la Antártida?

3. Análisis y resultados

Se analizó la evolución de los diferentes participantes en el acceso a la aventura gráfica y la resolución de los retos planteados. El volumen de participantes fue bastante fiel, con una media de accesos semanal de 1.503 alumnos/as. Muy relevante es comprobar cómo el volumen de accesos de la última semana es superior al de la primera, indicando la incorporación de participantes una vez iniciado el proyecto. Todos estos indicadores nos subrayan lo acertado de dos elementos del mismo:

• Distribución de contenidos y niveles, escalonados y supeditados a la superación de tareas. Esto permitió mantener el interés semana a semana, «enganchando» a los usuarios mucho más que si se hubieran mostrado todos los escenarios y contenidos de una vez.

• Eficacia del argumento y la guionización de los contenidos, haciendo que la semana de resolución del mismo, con la identificación del culpable, fuera una de las de mayores accesos. Buen indicador de inmersión de los participantes en la argumentación construida.

Un elemento importante en cuanto a información referida es el tiempo medio dedicado por los participantes a la estancia en la aventura gráfica. El tiempo medio de estancia estuvo en relación directa con el índice de dificultad, por tanto, su representación gráfica debería coincidir con la de una línea ascendente no demasiado acusada. Observemos (página anterior) los datos obtenidos en la Figura 1.

Como se comprueba en la figura la línea mantiene un nivel ascendente suave que duplica ampliamente el tiempo promedio del inicio con el registrado al final. A la vista del mismo comprobamos que el nivel de dificultad era el correcto para todo el desarrollo y abordaje de contenidos del proyecto. Veamos ahora los datos obtenidos por la muestra seleccionada en la encuesta pre y post proyecto.

A la vista de la figura observamos cómo el conocimiento previo al proyecto de la actividad investigadora desarrollada por España en la Antártida se reduce a un 18,7% de los participantes. Tras la participación en el proyecto el 100% conocen esta labor.

De forma semejante a la cuestión anterior, exploramos el conocimiento de los participantes sobre la actividad del Hespérides y la Base Gabriel de Castilla. Previamente a la participación en el proyecto la conocen un 11,37% de ellos, tras la participación en el mismo es el 100% el que tiene clara esa participación.

Asimismo, la labor del Ejército de Tierra y la Armada en la gestión, logística y apoyo en general de la labor investigadora española en la Antártida suele ser bastante desconocida, de ahí que nos interesara explorar tanto el conocimiento previo como su evolución con el proyecto. En la Figura 2, vemos cómo solo un 23,61% de los participantes afirma conocer la colaboración militar y naval, previamente al proyecto. Tras la participación, este porcentaje alcanza el 100%.

En esta cuestión observamos las valoraciones (de 1 a 10) realizadas por la muestra al posible retorno social de las investigaciones antárticas. Como vemos, la valoración preproyecto es bastante dura, con una moda de 5 y donde el gran volumen de las puntuaciones está desplazado hacia las puntuaciones más bajas. Contrasta con las puntuaciones postproyecto, donde la moda es de 8 y la curva de puntuaciones está claramente desplazada hacia la zona superior.

Posiblemente esta sea la pregunta más esperada de las realizadas, valorando el efecto del proyecto sobre las vocaciones CyT de los participantes. Como vemos en la figura, el interés previo por la profesión científica es señalado por un 9,39% de la muestra preproyecto, tras la participación, este porcentaje asciende a un 34,16%. Comprobamos cómo el interés profesional ha aumentado muy significativamente.

4. Conclusiones

Nuestro planteamiento general con la propuesta perseguía un elemento central en la gamificación, según Hamari y Koivisto (2013), «la gamificación tiene como principal objetivo influir en el comportamiento de las personas, independientemente de otros objetivos secundarios como el disfrute de las personas durante la realización de la actividad del juego». Nuestra propuesta pretendía ir mucho más allá de la proliferación de elementos gamificados que surgen al amparo del «do it my self» que señalábamos al inicio. Las limitaciones de ese tipo de desarrollos son obvias, restringiendo su alcance, efectos y posibilidades. El Proyecto Antártica ha sido la primera experiencia de gamificación transmedia diseñada a medida realizada en España para su aplicación masiva. Debido a ello, en su diseño inicial se pudieron tener en cuenta elementos difíciles de abordar con medios más limitados, como el componente transmedia, la programación a medida o la implicación de entidades procientíficas, por citar algunas.

En la estructura que se muestra en la figura anterior planteábamos la participación de todos los actores implicados, todos y cada uno de ellos por diferentes motivos. Institucionalmente es imprescindible coordinar actuaciones de divulgación científica entre ICTS, Museos de la Ciencia, Ferias y centros educativos como una forma de rentabilizar el esfuerzo de todas ellas y armonizando los intereses, necesidades, carencias, expectativas... Circunstancia común a profesorado, investigadores y familias; es esencial en los programas de divulgación y comunicación científica la proximidad del científico, como vía de eliminar clásicos estereotipos que aún persisten (científico = despistado, mal vestido, nada moderno, etc.). La proximidad a este colectivo, su cercanía (los participantes intercambiaron correos con los investigadores con dudas y comentarios sobre su trabajo), el interés de su trabajo para la sociedad, etc., son elementos claves que tuvimos muy presentes en el diseño del programa.

A la vista de los resultados hemos podido comprobar la consecución de los objetivos que inicialmente nos habíamos planteado. Los participantes han tenido oportunidad de conocer los componentes vocacionales de científicos en activo, además de comprobar el interés y el beneficio social de la actividad investigadora en general mientras manejaban metodología científica y aprendían el trabajo realizado desde una ICTS. El desconocimiento previo de la actividad investigadora española en la Antártida, la labor del Hespérides y la Base o el apoyo esencial del Ejército de Tierra y la Armada son alarmantes e indicadores del desconocimiento que afecta de raíz a las actuaciones y políticas CyT en España y, por ende, al descenso de vocaciones en esta área. En este sentido, nuestro objetivo general, el fomento del interés vocacional en las áreas profesionales CyT, se ha visto cumplido con un efecto claro y muy relevante entre los participantes.

De especial importancia para la consecución de nuestros objetivos nos parece la utilización de elementos próximos al target. Es clave contar con una línea argumental atractiva y, sobre todo, protagonistas con los que los participantes se puedan identificar con facilidad, en cuanto a gustos, hobbies o preferencias. La utilización de mensajería y publicaciones en redes de los protagonistas ha ayudado mucho a aumentar la inmersión de los participantes y la verosimilitud del argumento. Para esto no debemos olvidar la importancia de las ilustraciones y diseños, fiel reflejo de los escenarios reales, incluso la elaboración completa en 3D del buque Hespérides o la Base Gabriel de Castilla.

Con la realización de este proyecto se ha marcado un camino especialmente interesante para las administraciones públicas, la realización de programas gamificados a medida, con refuerzo transmedia, involucrando a todos los actores implicados en un esfuerzo común y coordinado. El esfuerzo económico inicial se amortiza rápidamente en los cursos siguientes, repitiendo la historia en grupos de alumnado diferente o modificando únicamente argumento y personajes. Un proyecto de este tipo puede dar lugar a modificaciones de argumento multiplicando los desarrollos distintos que utilizan el mismo núcleo de programación. La racionalización de la inversión pública en estas herramientas es ineludible si de verdad se desea implementar tecnologías innovadoras y eficaces a nivel educativo que vayan más allá de experiencias individuales aisladas.

Apoyos

Proyecto impulsado y financiado por la Fundación Telefónica con la participación de la Consejería de Educación de la Región de Murcia (por medio de la Fundación Séneca, Agencia Regional de Ciencia y Tecnología) y la colaboración del Comité Polar, la Armada y el Ejército de Tierra.

Referencias

All, A., Nunez-Castellar, E.P., & Van-Looy, J. (2014). Measuring effectiveness in digital game-based learning: A methodological review. International Journal of Serious Games, 1(2), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v1i2.18

Berkling, K., & Thomas, C. (2013). Gamification of a software engineering course and a detailed analysis of the factors that lead to it’s failure. International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning, ICL 2013, 525-530. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICL.2013.6644642

Brewer, R., Anthony, L., Brown, Q., Irwin, G., Nias, J., & Tate, B. (2013). Using gamification to motivate children to complete empirical studies in lab environments. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children - IDC ’13 (pp. 388-391). https://doi.org/10.1145/2485760.2485816

Chorney, A.I. (2012). Taking the game out of gamification. Dalhousie Journal of Interdisciplinary Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.5931/djim.v8i1.242

Coll, C., Mauri-Majós, M.T., & Onrubia-Goñi, J. (2008). Analyzing actual uses of ICT in formal educational contexts: A socio-cultural approach. Revista Electronica de Investigacion Educativa, 10(1), 1-18.

De-Pro, A., & Pérez, A. (2014). Actitudes de los alumnos de Primaria y Secundaria ante la visión dicotómica de la ciencia. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 32(3), 111-132. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/ensciencias.1015