(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== The p...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 930878139 to Lopez-Garcia et al 2017a) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 12:02, 27 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The paper aims at understanding the intersections between technology and the professional practices in some of the new trends in journalism that are using the new tools: multimedia journalism, immersive journal-ism and data journalism. The great dilemma facing journalism when training new professionals -especially the youngest- is not anymore the training in new technologies anymore. The main concern lies in taking ad-vantage of their skills to create a new computational model while keeping the essence of journalism. There is a twofold objective: answering questions about which tools are being used to produce pieces of news, and which kind of knowledge is needed in the present century. Based on the review of reports from profes-sional organizations and institutes, it was developed an exploratory research to 25 European and American journalists was developed. We have selected three cases of study. They allowed us to conclude that the technology matrix is going to remain and that change and digital process is not turning back and demands to evolve and adapt to new dynamics of work in multidisciplinary teams where the debate between journal-ists and technologists must be ongoing. Different approaches nourish the double way of skills and compe-tences in the profiles of the current technological journalist, which professionals perceive as a demand in the present ecosystem.

1. Introduction

This exploratory study reflects on the concern about the technological side of communication processes, which has been a constant since ancient times, from the first in-depth reflection on the issue by Plato to the electronic age, in which McLuhan analyses the role of technology in the communicative transfer (Núñez-Ladeveze, 2016).

The interest in this issue continues because contemporary journalism and technology are closely linked, in a complex and diverse way (Anderson, Bell, & Shirky, 2012; Lewis & Westlund, 2015). The change in news production allowed by technology has been assessed in the third millennium by Pavlik (2000), Boczkowski (2004), Deuze (2007), Stavelin (2013) or Rodgers (2015). The results of the transformations in the practices of journalism in this century are collected in research on the new newsroom models (Domingo & Paterson, 2011: Hermida, 2013; Reich, 2013), which agree in stressing the technological dimension of the new journalist profiles.

Digital technology is present in every dimension of current journalism and is shown in four different sides: when there is a low dependence on technologies in the production process (Human-centric journalism); when technology clearly facilitates the work (Technology-supported journalism); when journalists depend on technologies to produce contents (Technology-Infused journalism); and when technologies manage the news creation (Technology-oriented journalism) (Lewis& Westlund, 2016). The dimensions of technological journalism, in any of its approaches, indicate that the management of devices for the production and the journalistic work in the Internet of things requires a more technological journalist than the professional of the industrial era, in the 20th century.

1.1. The technological dimension of journalism

The transformations of journalism in recent years have entailed a more computational profile, which moves it closer to a multidisciplinary field where information and computation skills are required in various degrees of intensity (Codina, 2016). The search for information and verification, which compose the essential elements of journalism, is affected by this computational dimension, which shows a gap between journalists who are able to practice this journalism with a sound technological preparation, and those journalists who do not have it and find themselves in a transition phase. The technological dimension, which foreseeably will become more important in future journalism, offers, in present intersections, various journalistic trends. The values of journalism throughout history, such as truthfulness, accuracy and impartiality (Schudson, 2003), as well as the social and service roles of journalism that feed a pluralistic society (Kunelius, 2007) are still alive. Production systems, however, have changed, as well as the result of their manifestations in communication processes. Current practices are preferably arranged, as movements or specializations, in multimedia journalism, data journalism, immersive journalism and transmedia journalism. Technology instills society and culture, causing hybridizations that distinguish the current partnership human-machine (Hamilton, 2016), and strengthening the case for the need to recognize technologies as a defining element of the digital society.

The great dilemma facing journalism is not so much the incorporation of technologies to the professional practice as a set of tools, but the preparation of professionals with a more technological profile, with competences and skills to take advantage of the opportunities of the computational model, in which the software has taken the lead (Manovich, 2013), and in which dimensions that define the journalistic quality from a professional perspective remain stable: relevance, comprehensiveness, diversity, impartiality and accuracy (Kümpel & Springer, 2015). Training in journalism must have a “double route” that both enhances the knowledge of the essential elements of journalism and combines them with technology training. The focus of present journalism is on technology, but also on the quality of contents (Masip, 2016; Deuze, 2017).

1.2. Scientific literature to understand the context

Today´s technologies have made possible the empowerment of citizens (Jenkins, 2006) and have forced journalists to be better trained in technologies (Lewis & Westlund, 2016). The new required insights for news professionals range from the management of content systems (Rodgers, 2015) to algorithms (Diakopoulos, 2015), audience research (Tandoc, 2014), and big data and data processing (Bruns, 2016). Thus the four sides of the technological specificity needed by journalists are configured (Powers, 2012), to work on various devices and channels of the present media ecosystem.

Organizations and entities focus their attention on the challenge of ICT for media outlets and professionals since the late 20th century. The first report by the UNESCO in 1989 on Communication and Information warned of the change in the industry (the in-depth political, economic and technological transformations), as well as the document on the information 1997-1998. It was, however, the 1998 report on Communication by Lofty Maherzi (The media and the challenge of the new technologies), which drew global attention to the new defiances. A revolution in working methods was then predicted (Maherzi, 1998), with new dimensions for communication professionals, especially journalists.

Journalism, which has been linked since its emergence to technological innovation (Salaverría, 2010), is immersed in a far-reaching conversion (Casero, 2012). The technologies used by the media in production and dissemination processes, both traditional and digital natives (Cebrián-Herreros, 2009), have stepped up the range of professionals (Scolari, Micó, Navarro, & Pardo, 2008), who are increasingly using these tools that have become a kind of “lingua franca” for the work in the field of information and communication in the Network Society.

Journalists have played an active role in the dissemination of digital technologies (Geiß, Jackob, & Quiring, 2013), yet the truth is that before disseminating their duties they had to take up the challenge of knowing and using them as soon as possible to improve production and dissemination processes for information.

The working environment at companies, engaged in the renovation to compete and be updated with technologies, pushed professionals to quickly incorporate digital tools because they made work easy and showed their potential to improve journalistic practice (García-Avilés, 2007). Although professionals sometimes look down on new technologies, they have assessed the opportunities offered by these tools and have finally recognised their usefulness.

The effects and consequences of these technologies are the main topics of many research works, which analyse the new dimensions fostered by technology in the production of journalistic pieces for the media in the Network Society. Multimediality (Deuze, 2004), interactivity (Scolari, 2008), new audiences (Carpentier, Schrøder, & Hallett, 2014) and new ways of participation (Masip & al., 2015), customization (Thurman, 2011), memory and documentation (Guallar, 2011; Guallar & al., 2012), or mobility and new devices (Westlund, 2014), deserve particular attention. At the beginning of the present decade, many authors warned of the change in the models of journalism (Trench & Quinn, 2003) within a new labour framework with alternative production methods (Fish & Srinivasan, 2012), and others recently confirmed the dominant trends of the technological profile (Newman, 2016; Gómez-Calderón & al., 2017). The interest on the technological impact has increased in the last three years, after the call of the technological dimension made by Lev Manovich, when he warned of the prominence of the software (2013) as central command of technology-mediated communication. From then on, different works on age gaps when consuming communication from mobile devices appeared (Weis, 2013) on skills to produce news for these devices (Barum, 2016), on new techniques in social media (Tifentale & Manovich, 2014) and the need for emerging checking practices (Brandtzaeg, Lüders, Spangenberg, Rath-Wiggins, & Følstad, 2015) as well as their techniques (Bradshaw, 2015).

2. Material and methods

Based on the review of scientific production to contextualize the connection between the practice of journalism and technology, especially from the Internet, we wanted to understand how intersections between technology and the professional practice occur in some trends in journalism that use the most technological tools: multimedia journalism, immersive journalism, and data journalism. The goal has been to answer questions about the tools used by professionals when producing pieces of news with these techniques, what technological knowledge is required and those technological skills which were not needed for journalism in the 20th century but are demanded in the 21st century. The methodological approach is based on the case study and exploratory studies to emphasize the need to understand the cases in a comprehensive manner instead of dissecting them in decontextualized segments (Creswell, 2007; Yin, 2009). The case study, which emerged in the field of social science as a technique to understand various problems in their social context, and which is based on methods that provide insight into one or more cases in depth (Eisenhardt, 1989), allow us to understand the evolution towards a more technological profile of the journalist that works in the current media, with renewed narratives, the main innovation trends in the field in recent years and the reasons why.

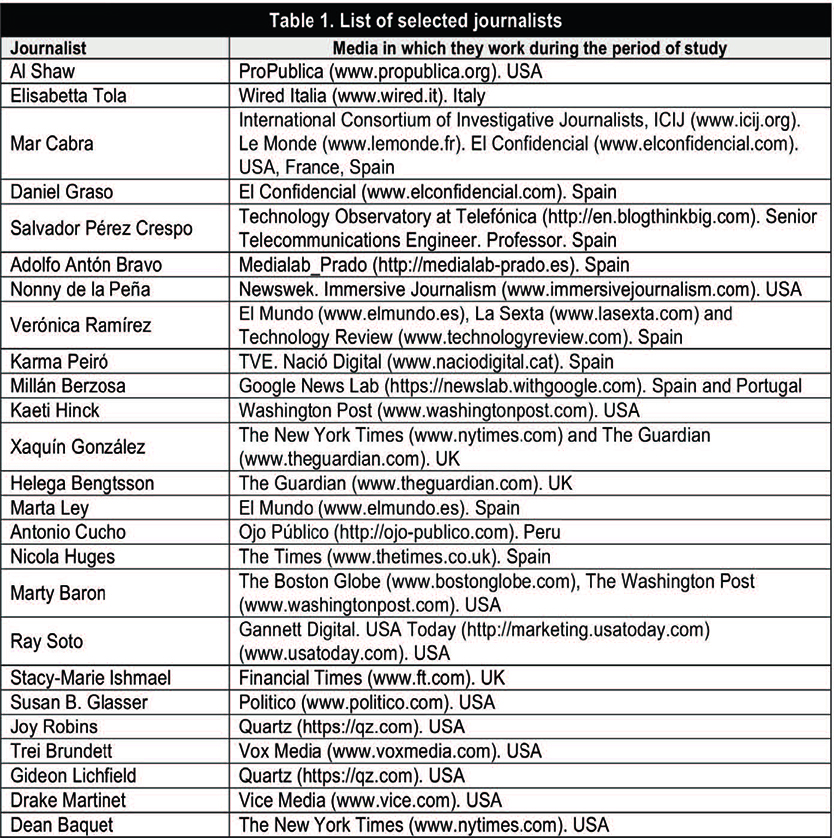

We also take over exploratory studies that help to increase familiarity with relatively unknown phenomena, to gather information for a more comprehensive research and to set priorities for further research (Dankhe, 1986). Exploratory studies, which are more versatile in terms of the method than descriptive and explanatory ones, are considered appropriate for this research, designed to remain open to the unexpected and to find previously unidentified perspectives, being interviews and focus groups the main instruments. The data shown are drawn from research that follows up regular projects conducted by journalists that work in the digital edition of various news media, both traditional and digital natives, in the USA and Europe during the past five years. The list of the 25 journalists below, chosen randomly to follow their statements and texts on technological change, professional profiles and the future of journalism, consists of professionals that held different positions in content development and management of network initiatives (traditional and digital natives). Both genres are included, as well as European and American professionals that are often involved in events on technology and journalism (notably, Spain, USA, and UK) (Table 1).

The list above indicates the media in which these professionals worked, as well as researchers and professors with applied experience over the study period. An analysis of the interviews conducted in the last five years has been carried out, including conferences in which the above mentioned participated, as well as those speeches available under open access, so that needed tools, knowledge and skills for daily work can be identified. Two pieces by the author were selected to analyse text, video, multimedia and interaction elements. Three out of the 25 journalists were selected for the case studies, applying narrative and research techniques criteria (immersive, data, multimedia and automation):

• Nonny De-la-Peña, one of the most relevant professionals in immersive journalism.

• Xaquín González, journalist and infographic designer at “The Guardian”, with experience in “The New York Times», “National Geographic” and Spanish media, for his expertise in multimedia and data visualization.

• Mar Cabra, one of the best known investigative journalists. Not only has she published the “Panama Papers” and the “Falciani List”, but she is also a member of the ICIJ.

The study was completed, following Krueger (1991), with a mini focus group. The starting point were the previous interviews with these experts and professionals and an open survey entitled “Working framework to outline competences and skills needed for current journalists”, whose questions were divided into three large blocks to obtain data on: basic knowledge on the functioning of present societies (know-how); abilities (command) of current techniques and tools (sum of key knowledge and abilities, skills); and attitudes in journalism (curiosity, analytical skills, reflective and critical perception and honesty). In the dimensions of the journalist´s technological profile, for instance, the survey and debate focused on aspects such as: technological fluency, specific tasks for journalists and communicators –profiles–, digital skills for data checking, accuracy and deepening in real time and through multimedia techniques: management of an audience, communities and impact data; and ongoing learning combining on-site and virtual initiatives. The data collected are intended to understand the way junior journalists work for new media and the required technological skills. The group is especially valuable to explore the ways in which these people create meaning and to understand a particular issue (Lunt & Livingstone, 1996; Krueger, 1991): technological skills in the professional exercise of certain journalism trends.

3. Analysis and results

3.1. Technology matrix

The evolution of the Network Society, with new forms of communication that characterize and define the technological context in which we operate, led to a general conviction among the main players in the media ecosystem on the need for changes in journalism to remain relevant in the 21st century (Picard, 2010). Media companies and journalism are facing critical challenges in the digital society with renewed products.

In the new digital environment, journalists are required to have competences in technologies to perform their duties, mainly search engines, content production, and dissemination. Journalists are asked to evolve, from a polyvalent profile (Scolari & al, 2008; Hamilton, 2016) to have RRSS development and management (Flores-Vivar, 2009; Hermida, 2016; Jensen, 2016,) management skills of their own business (Casero & al, 2013; Örnebring & Ferrer-Conill, 2016) or proficiency in cutting-edge technological tools to build renewed narratives (Peñafiel, 2015; Paulussen, 2016) in the innovations produced in newsrooms and the revolution of the mobile communication (Westlund, 2016). Different replies were received from the sector, according to reports on journalism from associations (in Spain, the Madrid Press Association, with its Annual Report on the Practice of Journalism) and from editors, mainly the WAN-IFRA (World Press Trend). Both mainly collect reticence by senior media professionals reluctant to changes, as well as the embrace to technological changes, driven from the very beginning by the youngest in general terms (World Editors Forum, 2016)1, and having unequal effects depending on the country both for journalism and democracy (Franco, 2009).

The best evidence of sensitivity with the explosion of technological innovation, online video, mobile communication and distribution in different platforms (Newman, 2016) is the unanimous recognition by professionals from the main media of the importance of the literacy in new technologies, which are allies of journalists in their daily work, as well as the need to constantly update on how to take advantage of the tools coming onto the market. That is the view of Nonny De-la-Peña, Xaquín González and Mar Cabra, also shared by, among others, senior journalists accountable for some of the world´s leading newspapers, as Marty Baron, editor of “The Washington Post” (Those are tools that were never available to newspapers before, and if we’re smart about it we can deploy them in a highly effective manner), said to Rob Hastings, from “The Independent”, in February 2016), and Dean Baquet, editor of “The New York Times” (“we have to move even faster because the world is shifting so quickly”, said in an interview with Ken Doctor, from Niemanlab.org, in 2016).

The technology matrix, surrounding professional profiles of journalists in the Network Society, has created a renewed dimension that affects the essence of the profession, which includes the search and inquiry, paperwork, the creation and display of messages, and the dissemination and management. Journalists are required to have a sound humanistic training, talent and technological skills.

3.2. Dual route

Journalists2 agree that their education should take a dual route where the essence remains – the elements of journalism as a technique of social communication and as the profession of journalism (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001), with a sound humanistic and communication training, as well as a proper training in technologies that include from “touching the code” to network structure, information architecture, manipulating data and programming. The dual route should act as the dual route theory of reading (Jobard, Crivelho, & Tzourio-Mazoyer, 2003)3, if we establish a simile of the process linked to understanding the brain and learning, in such a way that they make a connection that gives meaning to the various professional profiles, which from a basic versatility lead to specialisations.

The analysed professional perspectives do not even question that the historical foundations of journalism will change, although it is agreed that the historical background (social, political, economic, and technological) has shaped some journalism´s dimensions. They agree in understanding technologies as allies for the practice of journalism, with the complexities and problems they create, and as needed tools to explore renewed formats, narratives, pieces of news and communication products for the digital society.

Some journalists (Nonny De la Peña, Xaquín González and Mar Cabra, among others, who are between 25-30 and 45-50 years old, and who represent different profiles of visualization, immersive and data and investigative journalism), use techniques that combine the traditional processing of news with current technologies and emerging techniques, with distinct profiles and that have acquired a certain strength in the current model of content production for the media ecosystem of the Network Society. It is, as they agree in clarifying in their presentations and seminars, the beginning of new paths for a journalism, present journalism, turning its eyes towards the conquest of the future.

The tools for the search process have a technology matrix, especially those linked to online checking, and there is almost always a need for understanding how to structure what was achieved and how to query a database –to understand at least their elements to collaborate with engineers and to create more complex projects–. The use of collaborative tools has, therefore, become a need in current newsrooms and the display and edition demands challenges for teams, which must develop new narrative categories to integrate differential aspects of the narrative, production, and visual edition, with the same relevance than visual elements (González, 2016)4.

The search for newsworthy stories and their creation requires, in many cases, knowledge of the advantages of Google and Facebook algorithms as traffic sources and, above all, the appointment of integrated teams in which various profiles (engineers, designers, statisticians, photographs, videographers, audience editors), bring different perspectives for a final product with high-dose of added value for the news content the user receives. And although different techniques are used, work must also be done with material from the real word (Nonny De-la-Peña, 2015)5, to offer non-fiction stories.

To open new paths and make a difference in journalism, identifying all kind of technological tools is essential to collect a large amount of data, process them and make them understandable. The availability of data implies a basic requirement that empowers the journalist, so there is a need to use techniques and tools up to now unusual in newsrooms (Cabra, 2016)6. Journalists at the forefront in the use of current technologies agree: the message with added value crosses borders of the inverted pyramid, and its search, production, and dissemination imply not only current technologies but also competences and skills to work in teams with different profiles that provide renewed dimensions to nonfiction stories. From their perspective, the various profiles must go over a new path with competences and skills resulted from the hybridization of technological and humanistic dimensions.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Technology feeds and defines current professional profiles. Since the disappearance of those journalists that only produced text with their typewriter, who remained well into the second half of the 20th century, when the newsrooms computerization came up, and they became digital (Baer & Greenberger, 1987), the technological dimension has had an impact, to a greater or lesser extent, in the profiles of journalists that work in digital newsrooms, integrated at different levels but in a digitisation process of news (Boczkowski, 2004). This trend has been intensified in the third millennium, especially since the boom of full connectivity, social web, mobile communication, big data, the Internet of things and immersive technologies, among others. From the image of the “romantic journalist” with pencil and notebook, only a few concrete examples remain, as innovation in newsrooms, both traditional and digital natives, has changed profiles and working techniques (Paulussen, 2016; Westlund, 2016), which are now washed with digital tools.

The various professional profiles perceived by journalists at the moment, beyond concrete tools, have two central vectors. First, the essential elements of journalism, the set of precepts that have been built up over time and forged in communication processes throughout history, always under a humanistic and social perspective, more or less pronounced depending on the context. Second, the technological dimension, where it is not so much a question of knowing this or that tool, but understanding the rationale, entering different territories and having the knowledge for the individual work and the dialogue with interdisciplinary teams, which produce large proportion of the most complex pieces disseminated by current cyber media and that circulate on the flows of the present media ecosystem.

As noted by Xaquín González, “the narrative in journalism, ever-more visual, requires the establishment of interdisciplinary groups applying visualization techniques, so there is a need for developers, designers, statisticians, visualizers, and cartographers involved that understand each other and work in journalism”. Therefore, we must address the need to train journalists for a changing environment in which current technologies set transformation, which requires journalists to understand technologies and their approach and singularities but without overlooking the pillars of journalism. Besides, journalists should know the argot used in technology: “journalists may know more or less of programming, but if they do not know the argot, they suffer from rejection in those teams created to produce pieces of news that require the cooperation of various specialists”. (De-la-Peña, Cabra, & González.) That is why, professionals insist, “journalists need to know the history of technology to understand how systems work. If they do not have that view, they feel out of the working group”. The challenge is that the reporter acquires knowledge and has an updated training. What professionals who have certainly served as a basis for this research and as a sample for a great number of reports from professional organizations and institutes monitored in the Observatory of New Media (World Editors Forum; Informe Anual de la Profesión Periodística; Reuters Institute, among others) claim, is that the technology matrix will not only not disappear, but may increase, as the process of change and technologization cannot turn back. Therefore, to adapt and evolve is essential: “Journalists, being more or less technologists, need to have the knowledge to cooperate with other technological profiles, which every day have more to say to tell what happens in society. Programmers, systems technicians, software developers... belong to the new teams, and all of them have to enter into dialogue. If journalists do not understand what interlocutors are talking about, their role in teams will be residual”. This adaptation process of journalists towards a world that, until quite recently, was not their own, is complex but enriching, as it brings journalists added value. Therefore, these professionals must understand that the change is in how and not in what. Different approaches nourish the double way of skills and competences in the profiles of the current technological journalist, which professionals perceive as a demand in the present ecosystem.

Notes

1 References are extracted from the reports Trends in Newsrooms 2014, 2015 and 2016, and recent documents by the WAN-IFRA.

2 The statement is extracted from the analysed texts from the 25 selected journalists and the interviews of three chosen cases.

3 The dual route theory establishes a framework to describe what happens in the brain when reading aloud.

4 Contribution made by Xaquín González in 2016 in an interview by the authors of the text.

5 The statement is extracted from the explanations of Nonny De-la-Peña on her report on Syria, using virtual reality techniques.

6 Mar Cabra explained the knowledge of tools that allow for the collection of a large amount of data in order to make them understandable in the IV Spain´s Data Journalism Conference, in Madrid.

Funding Agency

Results included in this article belong to the exploratory works for the contextual and referential framework of the project News Uses and Preferences in the New Media arena in Spain: Journalism Models for Mobile devices (Reference: CSO2015-64662-C4-4-R), and the activities of the International Research Network on Communication Management (R2014/026 XESCOM).

References

Anderson, C.W., Bell, E., & Shirky, C. (2012). Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present. New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism-Columbia University.

Baer, W., & Greenberger, M. (1987). Consumer Electronic Publishing in the Competitive Environment. Journal of Communication, 37(1), 49-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1987.tb00967.x

Barum, I. (2016). Democratizing Journalism through Mobile Media : The Mojo Revolution. London: Routledge.

Boczkowski, P.J. (2004). Digitizing the News: Innovation in Online Newspapers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bradshaw, P. (2015). Scraping for Journalists. Lenpul.com. (http://goo.gl/zzxQsg) (2016-05-12).

Brandtzaeg, P.B., Lüders, M., Spangenberg, J., Rath-Wiggins, L., & Følstad, A. (2015). Emerging Journalistic Verification Practices Concerning Social Media. Journalism Practice, 10(3), 323-342. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1020331

Bruns, A. (2016). Big Data Analysis. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Carpentier, N., Schrøder, K.C., & Hallett, L. (Eds.) (2014). Audience Transformations: Shifting Audience Positions in Late Modernity. New York: Routledge.

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2012). Contenidos periodísticos y nuevos modelos de negocio: Evaluación de servi-cios digitales. El Profesional de la Información, 21(4), 341-346. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2012.jul.02

Casero-Ripollés, A., & Cullell-March, C. (2013). Periodismo emprendedor. Estrategias para incentivar el autoempleo periodístico como modelo de negocio. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 19, 681-690. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ESMP.2013.v19.42151

Cebrián-Herreros, M. (2009). Comunicación interactiva en los cibermedios. [Interactive Communication in the Cybermedia]. Comunicar, 33(XVII), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-02-001

Codina, Ll. (2016). Tres dimensiones del periodismo computacional. Intersecciones con las ciencias de la documentación. Anuario ThinkEPI, 10, 200-202. https://doi.org/10.3145/thinkepi.2016.41

Creswell, J.W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks-CA: Sage.

Dankhe, G. (1986). Investigación y comunicación. In C. Fernández-Collado & G. Dankhe (Eds.), La comuni-cación humana en ciencia social. México: McGraw-Hill.

Deuze, M. (2004). What is Multimedia Journalism. Journalism Studies, 5(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670042000211131

Deuze, M. (2007). Media Work. London: Polity Press.

Deuze, M. (2017). Considering a possible future for Digital Journalism. Revista Mediterránea de Comunica-ción, 8(1), 9-18. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2017.8.1.1

Diakopoulos, N. (2015). Algorithmic Accountability: Journalistic investigation of computational power structures. Digital Journalism, 3(3), 398-415. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.976411

Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.): The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Domingo, D., & Paterson, C.A. (Eds.) (2011). Making Online News: Newsroom Ethnographies in the Second Decade of Internet Journalism. New York: Peter Lang.

Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14, 532-550. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1989.4308385

Fish, A., & Srinivasan, R. (2012). Digital Labor is the New Killer App. New Media & Society, 14(1), 137-152. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1461444811412159

Flores-Vivar, J.M. (2009). Nuevos modelos de comunicación, perfiles y tendencias en las redes sociales. [New Models of Communication, Profiles and Trends in Social Networks]. Comunicar, 33(XVII), 73-81. https://doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-02-007

Franco, G. (2009). El impacto de las tecnologías digitales en el periodismo y la democracia en América Latina y el Caribe. Austin, Texas: Centro Knight para el Periodismo en las Américas de la Universidad de Texas. (http://goo.gl/CpeIL0) (2016-05-10).

García-Avilés, J.A. (2007). Nuevas tecnologías en el periodismo audiovisual. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas de Elche, 1(2), 59-75. (http://goo.gl/U9VK29) (2016-04-10).

Geiß, S., Jackob, N., & Quiring, O. (2013). The Impact of Communicating Digital Technologies: How Information and Communication Technology Journalists Conceptualize their Influence on the Audience and the Industry. New Media & Society, 15(7), 1058-1076. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812465597

Gómez-Calderón, B., Roses, S., & García-Borrego, M. (2017). Los nuevos perfiles profesionales del periodista desde la perspectiva académica española. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 8(1), 191-200. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2017.8.1.14

Guallar, J. (2011). La documentación en la prensa digital. Nuevas tendencias y perspectivas. In K. Meso (Presidencia), III Congreso Internacional de Ciberperiodismo y Web 2.0. UPV-EHU, Bilbao. (http://goo.gl/WJG1Yq) (2016-04-12).

Guallar, J., Abadal, E., & Codina, Ll. (2012). Hemerotecas de prensa digital. Evolución y tendencias. El Profesional de la Información, 21(6), 595-605. (http://goo.gl/yQrPES) (2016-05-10).

Hamilton, J.M. (2016). Hybrid News Practices. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Hermida (Eds.): The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Hermida, A. (2013). #Journalism: Reconfiguring Journalism Research about Twitter, on Tweet at a Time. Digi-tal Journalism, 1(3), 295-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.808456

Hermida, A. (2016). Social Media and News. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: NYU Press.

Jensen, J.L. (2016). The Social Sharing of News: Gatekeeping and Opinion Leadership on Twitter. In J.L. Jensen, M. Mortensen, & J. Ormen, News across Media. Production, Distribution and Consumption. New York: Routledge.

Jobard, G., Crivello, F., & Tzourio-Mazoyer, N. (2003). Evaluation of the Dual Route Theory of Reading: A Metanalysis of 35 Neuroimaging Studies. Neuroimage, 20(2), 693-712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00343-4

Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2001). The Elements of Journalism. What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Shoul Expect. New York: Crown Publishers.

Krueger, R.A. (1991). El grupo de discusión. Guía práctica para la investigación aplicada. Madrid: Pirámide.

Kunelius, R. (2007). Good Journalism. Journalism Studies, 7(5), 671-690. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700600890323

Kümpel, A.S., & Springer, N. (2015). Commenting Quality: Effects of User Comments on Perceptions of Journalistic Quality. In The Future of Journalism. Cardiff. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2016-3-353.

Lewis, S.C., & Westlund, O. (2015). Actors, Actants, Audiences, and Activities in Cross-Media News Work: A matrix and a research agenda. Digital Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.927986.

Lewis, S.C., & Westlund, O. (2016). Mapping the Human-Machine Divide in Journalism. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Lunt, P., & Livingstone, S. (1996). Rethinking the Focus Group in Media and Communications Research. Journal of Communication, 46(2), 79-98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1996.tb01475.x

Maherzi, L. (1998). World Communications Report. The Media and the Challenge of the New Technologies. Paris: Unesco Publishing. (http://goo.gl/luxaem) (2016-04-12).

Manovich, L. (2013). Software Takes Command. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Masip, P. (2016). Investigar el periodismo desde la perspectiva de las audiencias. El Profesional de la In-formación, 25(3), 323-330. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2016.may.01

Masip, P., Guallar, J., Sau, J., Ruiz-Caballero, C., & Peralta, M. (2015). News and Social Networks Audience Bahavior. El Profesional de la Información, 24(4), 363-370. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2015.jul.02

Neuman, N. (2016). Media, Journalism and Technology. Predictions 2016. Reuters Institute. (http:// goo.gl/iZZAC1) (2016-04-12).

Núñez-Ladevéze, L. (2016). Democracia, información y libertad de opinión en la era digital. In A. Casero-Ripollés (Coord.), Periodismo y democracia en el entorno digital. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Periodística, 25(3), 323-330. (http:// goo.gl/bJBw5a) (2016-05-08).

Paulussen, S (2016). Innovation in the Newsroom. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo, & A.

Pavlik, J. (2010). The Impact of Technology on Journalism. Journalism Studies, 1(2), 229-237. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700050028226

Peñafiel-Saiz, C. (2015). La Comunicación transmedia en el campo del periodismo. Supervivencia en el ecosistema digital. Telos, 100, 84-87. (http:// goo.gl/EM8RMr) (2016-05-08).

Picard, R. (2010). Value Creation and the Future of News Organizations. Why and how Journalism Must Change to Remain Relevant in the Twenty-first Century. Porto: Media XXI.

Powers, M. (2012). In Forms That Are Familiar and Yet-to-Be Invented: American Journalism and the Discourse of Technologically Specific Work. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 32(1), 24-43. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0196859911426009

Reich, Z. (2013). The Impact of Technology on News Reporting: A Longitudinal Perspective. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 90(3), 417-434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699013493789

Rodgers, S. (2015). Foreign Objects? Web Content Management Systems, Journalistic Cultures and the Ontology of Software. Journalism, 1(16), 16-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914545729

Salaverría, R. (2010). Estructura de la convergencia. In X. López & X Pereira (Coords.), Convergencia digital: reconfiguración de los medios de comunicación en España. Compostela: Universidade de Santiago.

Schudson, M. (2003). The Sociology of News. New York: W.W. Norton&Company Incorporated.

Scolari, C. (2008). Hipermediaciones. Elementos para una teoría de la Comunicación Digital Interactiva. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Scolari, C., Micó, J.L., Navarro, H., & Pardo, H. (2008). El periodista polivalente. Transformaciones en el perfil del periodista a partir de la digitalización de los medios audiovisuales catalanes. Zer, 13 (25), 37-60 (goo.gl/7EssW2) (2016-05-08)

Stavelin, E. (2013). Computational Journalism. When Journalism Meets Programming (PhD dissertation). The University of Bergen, Bergen. (http://goo.gl/jQQqdr) (2016-04-12)

Tandoc, E.C. (2014). Journalism is Twerking? How Web Analytics is Changing the Process of Gatekeeping. New Media & Society, 16(4), 559-575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814530541

Thurman, N. (2011). Making ‘The Daily Me’: Technology, Economics and Habit in the Mainstream Assimilation of Personalized News. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, 4(12), 395-415. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884910388228

Tifentale, A., & Monovich, L. (2014). SelfieCity: Exploring Photography and Self-Fashioning in Social Media. (http://goo.gl/ZNGYf8) (2016-05-08).

Trench, B., & Quinn, G. (2003). Online News and Changing Models of Journalism. Irish Communication Review, Vol. 9. (http://goo.gl/glMulH) (2016-06-10).

Weis, A.S. (2013). Exploring News Apps and Location-Based Services on the Smartphone. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 90(3), 435-456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699013493788.

Westlund, O. (2014). The Production and Consumption of Mobile News. In G. Goggin & L. Hjorth (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media. New York: Routledge. (http://goo.gl/B5K623) (2016-04-12).

Westlund, O. (2016). News Consumption across Media : Tracing the Revolutionary Uptake of Mobile News. In J.L. Jensen, M. Mortensen & J. Ormen, News across Media. Production, Distribution and Consumption. New York: Routledge.

World Editors Forum (Ed.) (2016). Trends in Newsrooms 2016. Paris: Wan-IFRA.

Yin, R.K. (2009). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks-CA: Sage.

Örnebring, H., & Ferrer-Conill, R. (2016). Outsourcing Newswork. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Este trabajo pretende conocer cómo se producen las intersecciones de la tecnología con la práctica profe-sional en algunas de las corrientes periodísticas que más emplean las nuevas herramientas: el periodismo multimedia, el periodismo inmersivo y el periodismo de datos. El gran dilema del periodismo en la prepara-ción de los profesionales (especialmente jóvenes) no pasa tanto por la incorporación de tecnologías y he-rramientas como por mejorar sus competencias y habilidades con un perfil que aproveche las oportunida-des del modelo computacional manteniendo la esencia periodística. El objetivo es doble: responder a las preguntas sobre qué herramientas emplean los profesionales para elaborar piezas periodísticas con estas técnicas y qué conocimientos y habilidades tecnológicas no eran precisas para el periodismo del siglo XX pero sí en el del siglo XXI. Partiendo de la revisión de informes de las organizaciones profesionales o insti-tutos de relevancia internacional se diseñó una investigación exploratoria sobre el trabajo de 25 periodistas europeos y americanos, y se eligieron tres casos de estudio que permiten concluir que la matriz tecnológica no solo no desaparecerá, sino que puede incrementarse porque el proceso de cambio y tecnologización no tiene marcha atrás y exige evolucionar y adaptarse a nuevas dinámicas de trabajo en equipos multidiscipli-nares donde el diálogo entre periodistas y tecnólogos debe ser fluido. Diferentes perspectivas alimentan la doble vía de las competencias y habilidades en los perfiles del actual periodista tecnólogo que los profe-sionales perciben que demanda el ecosistema actual.

1. Introducción

Este trabajo exploratorio analiza sobre la preocupación por el condicionamiento tecnológico de los procesos comunicativos que ha sido una constante desde la antigüedad, con la primera reflexión a fondo sobre el tema por parte de Platón, hasta la era electrónica, en que McLuhan analiza la tecnología en la transmisión comunicativa (Núñez-Ladeveze, 2016). El interés por esta cuestión se mantiene porque el periodismo contemporáneo y la tecnología están estrechamente relacionados, de manera compleja y diversa (Anderson, Bell, & Shirky, 2012; Lewis & Westlund, 2015). El cambio en la producción periodística por la tecnología ha sido analizado en el tercer milenio por Pavlik (2000), Boczkowski (2004), Deuze (2007), Stavelin (2013) o Rodgers (2015). Las consecuencias de las transformaciones de la práctica periodística durante el actual siglo están recogidas en investigaciones sobre los nuevos modelos redaccionales (Domingo & Paterson, 2011; Hermida, 2013; Reich, 2013), que coinciden en destacar la dimensión tecnológica del nuevo perfil del periodista.

La tecnología digital está presente en todas las dimensiones del periodismo actual y se manifiesta en cuatro facetas o estadios diferenciados: cuando hay una escasa dependencia de las tecnologías en el proceso de producción (Human-centric journalism), cuando la tecnología facilita claramente el trabajo (Technology-supported journalism), cuando los periodistas dependen de las tecnologías para producir contenidos (Technology-Infused journalism) y cuando las tecnologías gestionan la creación de noticias (Technology-oriented journalism) (Lewis & Westlund, 2016). Las dimensiones del periodismo tecnológico, en cualquiera de sus enfoques, indican que la gestión de los dispositivos para la producción y el trabajo periodístico en Internet de las cosas demanda un periodista más tecnológico que el profesional de la era industrial, en el siglo XX.

1.1. La dimensión tecnológica del periodismo

Las transformaciones del periodismo en los últimos años lo han arropado con un perfil más computacional que lo acerca a un campo interdisciplinar en el que se requieren competencias informacionales e informáticas en diversos grados de intensidad (Codina, 2016). La búsqueda y verificación de la información, que conforman elementos básicos del periodismo, se ven afectadas por esta dimensión computacional que muestra una brecha entre los periodistas con buena preparación tecnológica, capaces de practicar este periodismo, y los que no la tienen, que se encuentran limitados a la hora de realizar los cometidos en las redacciones de los medios digitales en esta fase de transición. La dimensión tecnológica, que previsiblemente tendrá más peso en el periodismo del futuro, nos depara, en las actuales intersecciones, diferentes corrientes periodísticas. Los valores del periodismo a lo largo de la historia como veracidad, exactitud e imparcialidad (Schudson, 2003), así como su función social y de servicio que alimenta una sociedad plural (Kunelius, 2007), siguen vivos pero los sistemas de producción han variado y el resultado de sus manifestaciones en los procesos comunicativos también. Las prácticas actuales se agrupan preferentemente, a modo de movimientos o especialidades, en el periodismo multimedia, el periodismo de datos, el periodismo inmersivo o el periodismo transmedia. La tecnología se instala en la sociedad y en la cultura provocando hibridaciones que caracterizan la relación actual hombre-máquina (Hamilton, 2016), y refuerzan los argumentos sobre la necesidad de reconocer las tecnologías como algo definitorio de la sociedad digital.

El gran dilema del periodismo no pasa tanto por la incorporación de las tecnologías a la práctica profesional como un conjunto de herramientas, como por la preparación de profesionales con un perfil más tecnológico, con competencias y habilidades para aprovechar las oportunidades del modelo computacional en el que el software ha tomado el mando (Manovich, 2013) y en el que permanecen estables dimensiones que desde la óptica profesional definen la calidad periodística: relevancia, exhaustividad, diversidad, imparcialidad y precisión (Kümpel & Springer, 2015). En la formación se debe establecer una «doble vía» que refuerce el conocimiento de los elementos básicos del periodismo y los combine con la capacitación tecnológica. El foco del periodismo actual está en la tecnología, pero también en la calidad de los contenidos (Masip, 2016; Deuze, 2017).

1.2. Literatura científica para entender el contexto

Las tecnologías actuales han hecho posible el empoderamiento de los ciudadanos (Jenkis, 2006) y han obligado a los periodistas a disponer de mejor formación tecnológica (Lewis & Westlund, 2016). Los nuevos conocimientos que precisan los profesionales de la información van desde la gestión de sistemas de contenido (Rodgers, 2015) hasta algoritmos (Diakopoulos, 2015), análisis de audiencias (Tandoc, 2014) o big data y procesamiento de datos (Bruns, 2016). Se configuran las cuatro facetas de la especificidad tecnológica que precisan los periodistas (Powers, 2012) para trabajar en los diferentes soportes y canales del ecosistema mediático actual.

Organizaciones y entidades llaman la atención sobre el desafío de las TIC para los medios y los profesionales desde finales del siglo XX. El primer informe de la UNESCO en 1989 sobre la Comunicación y la Información alertaba del cambio en el sector (las profundas transformaciones de orden político, económico y tecnológico), al igual que el documento sobre la información 1997-1998, aunque ha sido el informe de 1998 sobre la Comunicación, de Lofti Maherzi (Los medios frente al desafío de las nuevas tecnologías), el que hace la principal llamada de atención global sobre los nuevos retos. Se auguraba una revolución en los métodos de trabajo (Maherzi, 1998), con nuevas dimensiones para los profesionales de la comunicación, en especial para los periodistas.

El periodismo, que desde sus orígenes estuvo vinculado a las innovaciones tecnológicas (Salaverría, 2010), se halla inmerso en una profunda reconversión (Casero, 2012). Las tecnologías empleadas en los procesos de producción y difusión por los medios, tanto matriciales como nativos digitales (Cebrián-Herreros, 2009), han acelerado el espectro de los profesionales (Scolari, Micó, Navarro, & Pardo, 2008), que cada vez emplean más estas herramientas que se han convertido en una especie de «lengua franca» para el trabajo en el campo de la información y la comunicación en la sociedad Red.

Aunque los periodistas han tenido un papel activo en la divulgación de las tecnologías digitales (Geiß, Jackob, & Quiring, 2013), lo cierto es que antes de difundir sus cometidos han tenido que asumir el desafío de conocerlas y emplearlas lo antes posible para mejorar los procesos de producción y difusión de la información. El entorno laboral de las empresas, empeñadas en la renovación para competir y actualizarse en el ámbito tecnológico, empujó a los profesionales a incorporar con rapidez las herramientas digitales porque facilitaban el trabajo y mostraban su potencial para mejorar la práctica periodística (García-Avilés, 2007). Los profesionales, aunque a veces las miraron con recelo, han comprobado las oportunidades que ofrecían esas herramientas y han terminado reconociendo su utilidad.

Los efectos y consecuencias de esas tecnologías ocupan numerosos trabajos de investigación que analizan las nuevas dimensiones que alimentó la tecnología en la construcción de piezas periodísticas para los medios de la sociedad en Red. La multimedialidad (Deuze, 2004), interactividad (Scolari, 2008), las nuevas audiencias (Carpentier, Schrøder, & Hallett, 2014) y las nuevas formas de participación (Masip & al., 2015), la personalización (Thurman, 2011), memoria y documentación (Guallar, 2011; Guallar & al., 2012), o movilidad y nuevos dispositivos (Westlund, 2014) merecen especial atención. Varios autores advirtieron a principios de la actual década del cambio de modelo periodístico (Trench & Quinn, 2003), en un nuevo marco laboral con modos alternativos de producción (Fish & Srinivasan, 2012), y otros confirmaron recientemente las tendencias dominantes del perfil tecnológico (Newman, 2016; Gómez-Calderón & al., 2017). Este interés por el impacto tecnológico se intensifica en los últimos tres años, tras el aldabonazo de la dimensión tecnológica dado por Lev Manovich cuando alertó del protagonismo del software (2013) como mando central de la comunicación mediada tecnológicamente. A partir de ahí se publicaron trabajos sobre brechas por edades en el consumo de comunicación desde dispositivos móviles (Weis, 2013) y las destrezas para construir piezas para estos dispositivos (Barum, 2016), hasta nuevas técnicas en los medios sociales (Tifentale & Manovich, 2014) o la necesidad de prácticas emergentes de verificación (Brandtzaeg, Lüders, Spangenberg, Rath-Wiggins, & Følstad, 2015) y sus técnicas (Bradshaw, 2015).

2. Material y métodos

Partiendo de la revisión de la literatura científica de referencia para contextualizar la relación entre el ejercicio del periodismo y la tecnología, especialmente a partir de Internet, hemos querido conocer cómo se producen las intersecciones de la tecnología con la práctica profesional en algunas de las corrientes periodísticas que más emplean las herramientas tecnológicas: el periodismo multimedia, el periodismo inmersivo y el periodismo de datos. El objetivo ha sido responder a las preguntas de qué herramientas emplean los profesionales para elaborar piezas periodísticas con estas técnicas, qué conocimientos tecnológicos precisan y qué habilidades tecnológicas no se necesitaban para el periodismo del siglo XX pero sí en el periodismo del siglo XXI. La aproximación metodológica se realiza en el marco del estudio de caso y de los estudios exploratorios, para enfatizar la necesidad de comprender los casos de manera integral en lugar de diseccionarlos en segmentos descontextualizados (Creswell, 2007; Yin, 2009). El estudio de caso, que ha nacido en el campo de las ciencias sociales como una técnica para entender diferentes problemáticas en su contexto social, y que se basa en métodos que ayudan a comprender uno o más casos en profundidad (Eisenhardt, 1989), nos permite entender cómo se ha evolucionado hacia un perfil más tecnológico del periodista que trabaja en los medios actuales, con renovadas narrativas, en las principales tendencias de innovación en el sector en los últimos años y los motivos.

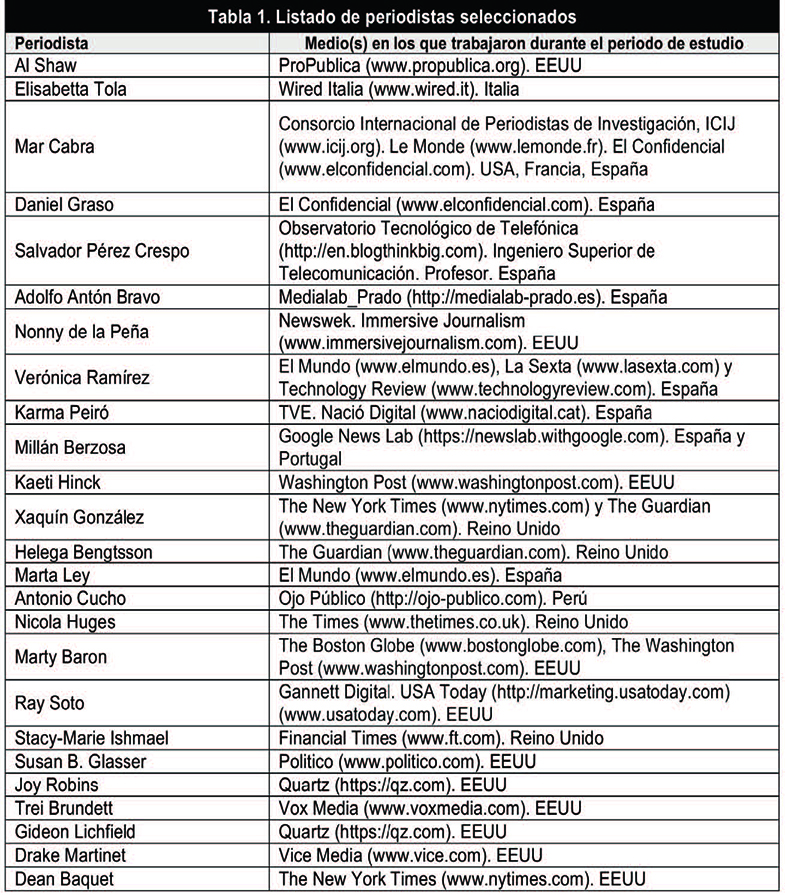

Asumimos, también, los estudios exploratorios que ayudan a aumentar la familiaridad con fenómenos relativamente desconocidos, obtener información para una investigación más completa y establecer prioridades para investigaciones posteriores (Dankhe, 1986). Los estudios exploratorios, que se caracterizan por ser más flexibles en su metodología que los descriptivos o explicativos, se consideran apropiados en esta investigación diseñada para ser sensible a lo inesperado y descubrir otros puntos de vista no identificados previamente mediante entrevistas y grupos de discusión como instrumentos fundamentales. Los datos que se presentan se extraen de una investigación que contempla un seguimiento periódico de los proyectos realizados por periodistas que trabajan en las versiones digitales de diversos medios informativos, tanto matriciales como nativos digitales, en América y Europa en los últimos cinco años. La lista de los 25 periodistas elegidos de forma aleatoria para seguir sus declaraciones y textos sobre el cambio tecnológico, los perfiles profesionales y el futuro del periodismo está formada por profesionales que ocupan diferentes puestos en la elaboración de contenidos y la gestión de iniciativas en la Red (matriciales y nativas digitales). Se incluyeron hombres y mujeres, así como profesionales europeos y americanos que participaron con asiduidad en eventos sobre tecnología y periodismo (en especial, en España, Estados Unidos y Reino Unido) (Tabla 1).

Se mencionan los medios para los que trabajaron estos profesionales (en algunos casos también investigadores y profesores con experiencia aplicada) durante el periodo del estudio en el que se analizaron las entrevistas concedidas durante los últimos cinco años y los congresos en los que han participado, y de los que se guardan sus intervenciones en bases de acceso abierto, para descubrir las herramientas, conocimientos y habilidades que precisan para su trabajo diario. Se seleccionaron dos piezas de cada autor para analizar el texto, vídeo, elementos multimedia e interacción. De estos veinticinco periodistas, aplicando criterios de narrativas y técnicas de investigación (inmersivas, datos, multimedia, automatización…), se eligieron tres para los estudios de caso:

• Nonny De-la-Peña, una de las profesionales más reconocidas en el campo del periodismo inmersivo.

• Xaquín González, periodista e infografista en «The Guardian», con experiencia en «The New York Times», «National Geografic» y en medios españoles, por su experiencia multimedia y como visualizador de datos.

• Mar Cabra, una de las periodistas de investigación más reconocidas que ha publicado sobre los «Papeles de Panamá» o la «Lista Falciani», y es miembro del Consorcio Internacional de Periodistas de Investigación (ICIJ).

El estudio se completó, siguiendo a Krueger (1991), con un mini-grupo de discusión. El punto de partida fueron las entrevistas previas con estos expertos y profesionales a partir de un cuestionario abierto titulado «Marco de trabajo para perfilar competencias y habilidades que deben tener los periodistas actuales», cuyas preguntas se estructuraron en tres grandes bloques para obtener información sobre: los conocimientos básicos del funcionamiento de las complejas sociedades actuales (saberes); las habilidades (dominio) de las técnicas y herramientas actuales (la suma de conocimientos claves más las habilidades es lo que se designa como aptitudes), y las actitudes periodísticas (curiosidad, capacidad de análisis, capacidad de reflexión y crítica, honestidad…). Como ejemplo, en las dimensiones del perfil tecnológico del periodista actual, el cuestionario y el debate se centraron en aspectos relacionados con: la fluidez tecnológica; los cometidos específicos del periodista o comunicador (perfiles), las competencias digitales para la verificación, precisión o profundización en tiempo real y a través de técnicas multimedia; la gestión de datos de audiencia, comunidades e impactos; o el aprendizaje continuo combinando iniciativas presenciales y en la Red. Con los datos recabados se pretende entender cómo los jóvenes periodistas trabajan para los nuevos medios y qué competencias tecnológicas precisan. El grupo es particularmente valioso para explorar las formas en que la gente construye significado y comprender un tema específico (Lunt & Livingstone, 1996; Krueger, 1991), en este caso las competencias tecnológicas para el ejercicio profesional en determinadas corrientes periodísticas.

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1. En la matriz tecnológica

La evolución de la sociedad red, con las nuevas formas de comunicación que caracterizan y definen el contexto tecnológico en el que nos movemos, alimentaron una convicción bastante generalizada entre los principales actores del ecosistema comunicativo sobre la necesidad de cambios del periodismo para seguir siendo relevante en el siglo XXI (Picard, 2010). Las empresas de comunicación y el periodismo afrontan desafíos decisivos para conquistar el futuro, lo que contribuye a que hagan esfuerzos para intervenir en la sociedad digital con renovados productos.

El nuevo entorno digital demanda a los periodistas, para el ejercicio profesional, competencias y habilidades derivadas de la tecnologización que tiene su cara más visible en los dispositivos de búsqueda, elaboración y difusión de contenidos. Al periodista se le pide desde un perfil polivalente (Scolari & al., 2008; Hamilton, 2016) hasta el aprovechamiento y gestión de redes sociales (Flores-Vivar, 2009; Hermida, 2016; Jensen, 2016), capacidad de gestión empresarial de su propia empresa (Casero & al., 2013; Örnebring & Ferrer-Conill, 2016) o de dominio de herramientas tecnológicas de última generación para la construcción de renovadas narrativas (Peñafiel, 2015; Paulussen, 2016) en el marco de las innovaciones que se producen en las redacciones y de la revolución de la comunicación móvil (Westlund, 2016).

Desde el sector hubo respuestas de todo tipo, según los informes de la profesión periodística de asociaciones (en España, Asociación de la Prensa de Madrid, con su Informe Anual de la Profesión Periodística) y de los editores, en especial de WAN-IFRA (World Press Trend). Recogen las reticencias formuladas, mayoritariamente, por profesionales del sector con bastantes años de actividad y pocas ganas de cambios, hasta el abrazo al cambio tecnológico desde el primer momento protagonizado, generalmente, por los más jóvenes (World Editors Forum, 2016)1, con efectos desiguales según los países tanto para el periodismo como para la democracia (Franco, 2009).

La mejor muestra de la sensibilidad con la explosión de innovación tecnológica, el vídeo online, la comunicación móvil y la distribución en diferentes plataformas (Newman, 2016) es el reconocimiento unánime por los profesionales de algunos de los principales medios de la importancia del dominio de las tecnologías actuales, que son aliadas de los periodistas en su trabajo, así como la necesidad de una actualización constante sobre cómo aprovechar las herramientas que aparecen en el mercado. Es el punto de vista de Nonny De-la-Peña, Xaquín González y Mar Cabra que también comparten, entre otros, periodistas veteranos y responsables de alguno de los principales diarios del mundo, como Marty Baron, director del «The Washington Post» («hay que aprovechar al máximo las herramientas que antes no estaban disponibles para los diarios», dijo a Rob Hastings, de «The Independent» en febrero de 2016), o Dean Baquet, director de «The New York Times» («tenemos que ser más rápidos en los cambios tecnológicos porque el mundo está mudando muy rápidamente», dijo en una entrevista a Ken Doctor, de Niemanlab.org, en 2016).

La matriz tecnológica, que envuelve los perfiles profesionales de los periodistas en la sociedad red, ha conformado una renovada dimensión que impregna lo básico de la actividad profesional, que incluye desde la búsqueda e indagación hasta la documentación, la construcción del mensaje y su presentación, y la difusión y gestión. Al periodista se le pide una buena formación humanística, talento y habilidades tecnológicas.

3.2. Una doble vía

Los periodistas2 coinciden al afirmar que en la formación hay que establecer una doble vía donde lo básico permanece –los elementos básicos del periodismo como técnica de comunicación social y profesión periodística (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001)– con una buena formación humanística y comunicológica, a lo que hay que añadir una buena formación tecnológica que incluye desde «tocar código» hasta estructura de redes, arquitectura de la información, manipular datos y programar. Las dos vías deben actuar, a modo de los principios de la teoría de la «doble ruta» para la lectura (Jobard, Crivelho, & Tzourio-Mazoyer, 2003)3, si empleamos un símil del proceso relacionado con la comprensión del cerebro y el aprendizaje, de tal forma que confluyan en una unión que dote de sentido los diferentes perfiles profesionales, que desde una polivalencia básica desembocan en especializaciones.

En las visiones profesionales analizadas ni siquiera se pone en duda que los fundamentos históricos del periodismo vayan a cambiar, aunque se admite que el contexto histórico (social, político, económico y tecnológico) ha moldeado algunas de sus dimensiones. Coinciden en presentar las tecnologías como aliadas para la actividad profesional, con sus complejidades y las problemáticas que alimentan, y como herramientas necesarias para explorar renovados formatos, narrativas, piezas periodísticas y productos comunicativos para la sociedad digital.

Algunos periodistas (Nonny De-la-Peña, Xaquín González y Mar Cabra, entre otros, que se encuentran en una franja de edad entre los 25-30 y los 45-50 años, y que representan perfiles actuales de visualización, inmersivo y datos e investigación) trabajan con técnicas que combinan el tratamiento tradicional de las noticias con las tecnologías actuales y técnicas emergentes, con perfiles diferenciados y que han conseguido cierta solidez en el modelo actual de producción de contenidos para el ecosistema comunicativo de la sociedad red. Es, como ellos coinciden en precisar en sus presentaciones y en los seminarios que imparten, el inicio de nuevos caminos para un periodismo, el del presente, pero con la mirada puesta en la conquista del futuro.

Las herramientas para el proceso de búsqueda tienen matriz tecnológica, en especial las de verificación en Red, y casi siempre surge la necesidad de entender cómo estructurar lo conseguido y cómo interrogar a una base de datos –al menos entender sus elementos para colaborar con ingenieros y crear proyectos más complejos–. El empleo de herramientas colaborativas se ha convertido en necesidad en las redacciones actuales y la presentación y edición es un desafío para equipos que deben desarrollar nuevas categorías narrativas para integrar los aspectos diferenciales de narrativa, producción y edición visual, con el mismo peso que los elementos visuales (González, 2016)4.

La búsqueda y construcción de historias de interés demanda, en muchos casos, conocer las ventajas de los algoritmos de Google y Facebook como fuentes de tráfico, y, sobre todo, conformar equipos integrados en los que distintos perfiles (ingenieros, diseñadores, estadísticos, fotógrafos, videógrafos, editores de audiencia…) aportan puntos de vista para un producto final con altas dosis de valor añadido para el contenido informativo que llega al usuario. Y, aunque se emplean distintas técnicas, siempre hay que trabajar con material que proceda del mundo real (Nonny De-la-Peña, 2015)5 para ofrecer relatos de no ficción.

Para abrir nuevos caminos y marcar diferencias en el campo periodístico, hay que rastrear con todo tipo de herramientas tecnológicas para recabar grandes cantidades de datos, procesarlos y hacerlos comprensibles: como disponer de los datos implica un requisito básico y empodera al periodista, hay que emplear técnicas y herramientas hasta ahora poco habituales en las redacciones de los medios (Cabra, 2016)6.

Los periodistas que ocupan puestos de vanguardia en el empleo de tecnologías actuales coinciden: el mensaje con valor añadido traspasa las fronteras de la pirámide invertida, y su búsqueda, realización y difusión precisan no solo tecnologías actuales, sino competencias y habilidades, para trabajar en equipos con distintos perfiles que aportan renovadas dimensiones al relato de no ficción. Desde su punto de vista, es solo el comienzo de un camino que deben recorrer diferentes perfiles con competencias y habilidades de una matriz fruto del mestizaje entre las dimensiones tecnológica y humanística.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

La tecnología alimenta y define los actuales perfiles profesionales. Desde la desaparición del periodista que solo elaboraba el texto en su máquina de escribir, que ha permanecido hasta bien entrada la segunda mitad del siglo XX, cuando llega la informatización a las redacciones y se hacen electrónicas (Baer & Greenberger, 1987), la dimensión tecnológica ha puesto pinceladas, más o menos gruesas, en los perfiles de los periodistas que trabajan en redacciones informatizadas, integradas en distintos niveles pero en un proceso de digitalización de las noticias (Boczkowski, 2004). Tendencia que se agudiza en el tercer milenio, en especial desde el auge de la conectividad total, la web social, la comunicación móvil, el «big data», el Internet de las cosas y las tecnologías inmersivas, entre otras. De la imagen del «periodista romántico», con lápiz y blog de notas, solo quedan algunos ejemplos puntuales porque la innovación en las redacciones, tanto de medios tradicionales como de nativos digitales, ha cambiado el perfil y las técnicas de trabajo (Paulussen, 2016; Westlund, 2016), ahora empapadas de herramientas digitales.

Los diferentes perfiles profesionales que perciben los periodistas en la actualidad, al margen de las herramientas concretas, cuentan con dos vectores centrales: los elementos básicos o fundamentos del periodismo, el conjunto de preceptos que se han sedimentado a lo largo del tiempo y forjado en procesos comunicativos a lo largo de la historia, siempre bajo un manto humanista y social, más o menos acentuado según los contextos; y la dimensión tecnológica, donde no se trata tanto de conocer esta o aquella herramienta como de entender los fundamentos, adentrarse en los diferentes territorios y disponer de conocimientos para el trabajo individual o para el diálogo en los equipos interdisciplinares que acometen buena parte de las piezas más complejas que difunden los cibermedios actuales y que circulan por los flujos del ecosistema comunicativo actual.

Como sostiene Xaquín González, «la narrativa periodística, cada vez más visual, exige crear equipos interdisciplinares que apliquen técnicas de visualización, para lo que se necesitan desarrolladores, diseñadores, estadísticos, visualizadores y cartógrafos que se entienden y trabajan desde el periodismo». Por ello, hay que afrontar la necesidad de preparar a los periodistas para un entorno cambiante en el que las actuales tecnologías marcan las transformaciones, lo que obliga a entender su planteamiento y sus singularidades, pero sin descuidar los fundamentos periodísticos. El periodista, además, debe conocer la jerga que se utiliza en la tecnología: «el periodista puede conocer más o menos de programación pero, si no conoce la jerga, sufre rechazo en los equipos que se crean para confeccionar las piezas periodísticas que exigen la colaboración de varios especialistas» (De-la-Peña, Cabra, & González). Por eso, insisten los profesionales, «el periodista tiene que entender la historia de la tecnología para comprender cómo actúan los sistemas. Si no tiene esa visión, se siente fuera de juego en el trabajo en equipo». El reto está en que el informador adquiera esos conocimientos y tenga una formación actualizada. Lo que afirman los profesionales, ciertamente los que han servido de base para la investigación en la que se sustenta este artículo y los que sirven de muestra para un gran número de informes de las organizaciones profesionales o institutos que se siguen en el Observatorio de Novos Medios (World Editors Forum; Informe Anual de la Profesión Periodística; Reuters Institut, entre otros), es que la matriz tecnológica no solo no desaparecerá, sino que puede incrementarse porque el proceso de cambio y tecnologización no tiene marcha atrás. Por eso, adaptarse y evolucionar es imprescindible: «El periodista, sea más o menos tecnólogo, tiene que disponer de conocimientos para cooperar con otros perfiles tecnológicos que cada día tienen más que decir para contar lo que pasa en la sociedad. Programadores, técnicos de sistemas, desarrolladores de software... forman parte de los nuevos equipos y todos tienen que dialogar. Si el periodista no entiende lo que hablan sus otros interlocutores, su papel en los equipos será residual». Este proceso de adaptación del periodista hacia un mundo que, hasta hace poco, no era el suyo es complejo pero enriquecedor ya que le aporta valor añadido. Por ello, el periodista tiene que entender que el cambio está en el cómo y no en el qué.

Diferentes perspectivas alimentan la doble vía que define las competencias y habilidades que conforman los perfiles del periodismo, que desemboca en el proceso del actual periodista tecnólogo que los profesionales perciben que demanda el ecosistema actual.

Notas

1 Las referencias se extraen de los informes Trends in Newsrooms 2014, 2015 y 2016, y documentos de la WAN-IFRA de los últimos años.

2 La afirmación se extrae de los textos analizados de los 25 periodistas seleccionados y de las entrevistas de los tres casos elegidos.

3 La teoría de la «doble ruta» establece un marco para la descripción de lo que sucede en el cerebro con la lectura al nivel de la palabra.

4 Aportaciones de Xaquín González realizadas en 2016 en una entrevista por parte de los autores del texto.

5 La afirmación parte de las explicaciones de Nonny De-la-Peña sobre su reportaje sobre Siria empleando técnicas de realidad virtual.

6 Mar Cabra explicó el domino de herramientas que permitan recabar gran cantidad de datos para hacerlos comprensibles en las IV Jornadas Periodismo de Datos, en Madrid.

Apoyos

Los resultados de este artículo forman parte de los trabajos exploratorios para el marco contextual y referencial del proyecto «Usos y preferencias informativas en el nuevo mapa de medios en España: modelos de periodismo para dispositivos móviles» (Referencia: CSO2015-64662-C4-4-R), y de las actividades de la Red Internacional de Investigación de Gestión de la Comunicación (R2014/026 XESCOM).

Referencias

Anderson, C.W., Bell, E., & Shirky, C. (2012). Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present. New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism-Columbia University.

Baer, W., & Greenberger, M. (1987). Consumer Electronic Publishing in the Competitive Environment. Journal of Communication, 37(1), 49-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1987.tb00967.x

Barum, I. (2016). Democratizing Journalism through Mobile Media : The Mojo Revolution. London: Routledge.

Boczkowski, P.J. (2004). Digitizing the News: Innovation in Online Newspapers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bradshaw, P. (2015). Scraping for Journalists. Lenpul.com. (http://goo.gl/zzxQsg) (2016-05-12).

Brandtzaeg, P.B., Lüders, M., Spangenberg, J., Rath-Wiggins, L., & Følstad, A. (2015). Emerging Journalistic Verification Practices Concerning Social Media. Journalism Practice, 10(3), 323-342. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1020331

Bruns, A. (2016). Big Data Analysis. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Carpentier, N., Schrøder, K.C., & Hallett, L. (Eds.) (2014). Audience Transformations: Shifting Audience Positions in Late Modernity. New York: Routledge.

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2012). Contenidos periodísticos y nuevos modelos de negocio: Evaluación de servi-cios digitales. El Profesional de la Información, 21(4), 341-346. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2012.jul.02

Casero-Ripollés, A., & Cullell-March, C. (2013). Periodismo emprendedor. Estrategias para incentivar el autoempleo periodístico como modelo de negocio. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 19, 681-690. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ESMP.2013.v19.42151

Cebrián-Herreros, M. (2009). Comunicación interactiva en los cibermedios. [Interactive Communication in the Cybermedia]. Comunicar, 33(XVII), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-02-001

Codina, Ll. (2016). Tres dimensiones del periodismo computacional. Intersecciones con las ciencias de la documentación. Anuario ThinkEPI, 10, 200-202. https://doi.org/10.3145/thinkepi.2016.41

Creswell, J.W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks-CA: Sage.

Dankhe, G. (1986). Investigación y comunicación. In C. Fernández-Collado & G. Dankhe (Eds.), La comuni-cación humana en ciencia social. México: McGraw-Hill.

Deuze, M. (2004). What is Multimedia Journalism. Journalism Studies, 5(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670042000211131

Deuze, M. (2007). Media Work. London: Polity Press.

Deuze, M. (2017). Considering a possible future for Digital Journalism. Revista Mediterránea de Comunica-ción, 8(1), 9-18. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2017.8.1.1

Diakopoulos, N. (2015). Algorithmic Accountability: Journalistic investigation of computational power structures. Digital Journalism, 3(3), 398-415. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.976411

Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.): The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Domingo, D., & Paterson, C.A. (Eds.) (2011). Making Online News: Newsroom Ethnographies in the Second Decade of Internet Journalism. New York: Peter Lang.

Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14, 532-550. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1989.4308385

Fish, A., & Srinivasan, R. (2012). Digital Labor is the New Killer App. New Media & Society, 14(1), 137-152. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1461444811412159

Flores-Vivar, J.M. (2009). Nuevos modelos de comunicación, perfiles y tendencias en las redes sociales. [New Models of Communication, Profiles and Trends in Social Networks]. Comunicar, 33(XVII), 73-81. https://doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-02-007

Franco, G. (2009). El impacto de las tecnologías digitales en el periodismo y la democracia en América Latina y el Caribe. Austin, Texas: Centro Knight para el Periodismo en las Américas de la Universidad de Texas. (http://goo.gl/CpeIL0) (2016-05-10).

García-Avilés, J.A. (2007). Nuevas tecnologías en el periodismo audiovisual. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas de Elche, 1(2), 59-75. (http://goo.gl/U9VK29) (2016-04-10).

Geiß, S., Jackob, N., & Quiring, O. (2013). The Impact of Communicating Digital Technologies: How Information and Communication Technology Journalists Conceptualize their Influence on the Audience and the Industry. New Media & Society, 15(7), 1058-1076. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812465597

Gómez-Calderón, B., Roses, S., & García-Borrego, M. (2017). Los nuevos perfiles profesionales del periodista desde la perspectiva académica española. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 8(1), 191-200. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2017.8.1.14

Guallar, J. (2011). La documentación en la prensa digital. Nuevas tendencias y perspectivas. In K. Meso (Presidencia), III Congreso Internacional de Ciberperiodismo y Web 2.0. UPV-EHU, Bilbao. (http://goo.gl/WJG1Yq) (2016-04-12).

Guallar, J., Abadal, E., & Codina, Ll. (2012). Hemerotecas de prensa digital. Evolución y tendencias. El Profesional de la Información, 21(6), 595-605. (http://goo.gl/yQrPES) (2016-05-10).

Hamilton, J.M. (2016). Hybrid News Practices. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Hermida (Eds.): The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Hermida, A. (2013). #Journalism: Reconfiguring Journalism Research about Twitter, on Tweet at a Time. Digi-tal Journalism, 1(3), 295-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.808456

Hermida, A. (2016). Social Media and News. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: NYU Press.

Jensen, J.L. (2016). The Social Sharing of News: Gatekeeping and Opinion Leadership on Twitter. In J.L. Jensen, M. Mortensen, & J. Ormen, News across Media. Production, Distribution and Consumption. New York: Routledge.

Jobard, G., Crivello, F., & Tzourio-Mazoyer, N. (2003). Evaluation of the Dual Route Theory of Reading: A Metanalysis of 35 Neuroimaging Studies. Neuroimage, 20(2), 693-712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00343-4

Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2001). The Elements of Journalism. What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Shoul Expect. New York: Crown Publishers.

Krueger, R.A. (1991). El grupo de discusión. Guía práctica para la investigación aplicada. Madrid: Pirámide.

Kunelius, R. (2007). Good Journalism. Journalism Studies, 7(5), 671-690. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700600890323

Kümpel, A.S., & Springer, N. (2015). Commenting Quality: Effects of User Comments on Perceptions of Journalistic Quality. In The Future of Journalism. Cardiff. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2016-3-353.

Lewis, S.C., & Westlund, O. (2015). Actors, Actants, Audiences, and Activities in Cross-Media News Work: A matrix and a research agenda. Digital Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.927986.

Lewis, S.C., & Westlund, O. (2016). Mapping the Human-Machine Divide in Journalism. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

Lunt, P., & Livingstone, S. (1996). Rethinking the Focus Group in Media and Communications Research. Journal of Communication, 46(2), 79-98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1996.tb01475.x

Maherzi, L. (1998). World Communications Report. The Media and the Challenge of the New Technologies. Paris: Unesco Publishing. (http://goo.gl/luxaem) (2016-04-12).